Abstract

Introduction:

Anxiety sensitivity (AS), defined as the extent to which individuals believe anxiety and internal sensations have harmful consequences, is associated with the maintenance and relapse of smoking. Yet, little is known about how AS interplays with negative affect during the quit process in terms of smoking behavior. To address this gap, the current study examined the dynamic interplay between AS, negative affect, and smoking lapse behavior during the course of a self-guided (unaided) quit attempt.

Methods:

Fifty-four participants (33.3% female; Mage = 34.6, SD = 13.8) completed ecological momentary assessment procedures, reporting on negative affect and smoking status via a handheld computer device, three times per day for the initial 14 days of the self-guided cessation attempt.

Results:

As expected, a significant interaction was observed, such that participants characterized by high levels of AS were at a higher risk of smoking on days when negative affect was high (relative to low). Results also revealed a significant interaction between AS and daily smoking lapse behavior in terms of daily change in negative affect. Participants characterized by high levels of AS reported significant increases in same-day negative affect on days when they endorsed smoking relative to days they endorsed abstinence.

Conclusions:

This study provides novel information about the nature of AS, negative affect, and smoking behavior during a quit attempt. Results suggest there is a need for specialized intervention strategies to enhance smoking outcome among this high-risk group that will meet their unique “affective needs.”

Implications:

The current study underscores the importance of developing specialized smoking cessation interventions for smokers with emotional vulnerabilities.

Introduction

Anxiety symptoms and disorders are associated with the maintenance and relapse of smoking. 1 One promising means of elucidating the role of anxiety in cigarette use is to investigate the influence of transdiagnostic psychological vulnerability factors; factors that underpin anxiety-related conditions on smoking. Anxiety sensitivity (AS), defined as the fear of anxiety and internal (interoceptive) states, 2 is one such transdiagnostic factor. AS is a relatively stable, yet malleable, 3 cognitive-based individual difference factor. 2 AS is empirically and theoretically distinguishable from anxiety symptoms as well as other negative affect states such as depressive symptoms. 4

There is strong evidence for the role of AS in the maintenance of smoking and smoking cessation failure. Specifically, AS is positively correlated with smoking motives to reduce negative affect 5 and beliefs that smoking will reduce negative affect. 6 Importantly, high AS is related to greater odds of early smoking lapse and relapse during quit attempts. 7 , 8 These observed AS-smoking relations are not better explained by smoking rate, gender, other concurrent substance use (eg, alcohol, cannabis), panic attack history, or trait-like negative mood propensity. 6 Consistent with this account, a recent study found that AS explained (mediated) the association between emotional disorders (ie, anxiety and depressive disorders) and nicotine dependence, barriers to cessation, and severity of problematic symptoms while quitting. 9 Such findings underscore the importance of incorporating AS in theoretical models addressing smoking cessation among emotionally vulnerable smokers.

There is relatively little empirical information on the impact of AS on the expression of negative affective states during periods of abstinence. Negative affect has been posited to play a central role underlying smoking motivation. According to this theoretical perspective, the degree to which smoking alleviates affective distress is a critical determinant of the negatively reinforcing power of smoking. 10 Negative affect demonstrates unique relations to cessation outcomes, 11–13 with negative affect states (particularly anxiety-related symptoms), often cited as common antecedents to smoking lapse and relapse. 14 , 15 There is also some evidence that suggests smoking may serves to reduce negative affect and improve negative mood states following cigarette administration. 16–18 For example, in a study of nontreatment-seeking smokers, negative mood ratings were lowest immediately after smoking compared with immediately before smoking and at random times of day. 17 While limited, available work suggests that AS is associated with the exacerbation of negative affect during cessation. 18 Individuals characterized by higher prequit levels of AS tend to experience an increase in negative mood states (ie, irritability, frustration, anxiety, depression) during the initial period of cessation, relative to their low AS counterparts. 19 Other work indicates that high levels of AS are associated with increases in positive affect after cigarette smoking, 20 and smoking serves to reduce anxiety following stress exposure among high AS smokers. 21

Although promising, past work on AS and negative affect is limited in two key ways. First, prior studies have yet to comprehensively examine these processes simultaneously, and instead, have modeled them largely separately as distinct processes. Therefore, it is unclear how AS may interact with negative affect in relation to cessation outcome during a quit attempt. It is possible that smokers with higher levels of AS may be more likely to experience smoking lapse during a quit attempt, especially when experiencing subjectively high levels of negative affect. Likewise, research has yet to evaluate how daily smoking behavior (smoking vs. abstinence) during a quit attempt, in the context of elevated AS, may impact the subjective experience of negative affect. That is, the impact of AS on negative mood states likely may vary as a function of daily smoking lapse status during the quit attempt. Addressing these gaps in the literature is critical to understand how AS, negative affect, and smoking behavior may synergistically function to promote poor cessation outcomes.

Second, the AS-smoking literature has yet to incorporate methodological advances in ambulatory Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) of negative affective states in “real time.” 22 EMA methodologies provide investigators with the capability to complete fine-grained monitoring of theoretically-relevant processes (eg, negative affect, smoking lapse behavior) and in real-world environments with personally-relevant cues and triggers to examine variability over time. 23 Applying EMA to this program of work may yield key insights into the affective and drug-state mechanisms linking AS to early lapse and relapse.

The aim of the present investigation was to examine, in the context of a self-guided (unaided; no psychosocial or pharmacological intervention) quit attempt, prequit levels of AS in terms of the interplay with daily experiences of abstinence-induced negative affect and smoking lapse behavior during the 14 days of a quit attempt. First, the main and interactive effects of prequit AS and time were tested in the prediction of between-day changes in negative affect. It was hypothesized that higher prequit levels of AS would be associated with: (1) greater intensity of negative affect experienced on quit day (intercept); and (2) increases in negative affect across the quit period (slope). Second, the main and interactive effects of prequit AS and between-day smoking lapse behavior (smoking vs. abstinence) were tested in terms of the prediction of between-day changes in negative affect. It was hypothesized that AS would significantly interact with daily smoking status to predict same-day negative affect, such that participants characterized by high levels of AS would experience significant decreases in same-day negative affect on days when they endorse smoking (relative to days they endorse abstinence). Third, the main and interactive effects of prequit AS and between-day changes in negative affect were tested in terms of the prediction of same-day smoking lapse behavior (smoking vs. abstinence) during the quit attempt. Here, it was hypothesized that AS would significantly interact with between-day changes in negative affect during the quit period to predict same-day smoking lapse behavior, such that participants characterized by high levels of AS would be at significantly higher risk of smoking on days when negative affect was high.

Methods

Participants

An initial 84 participants met eligibility criteria for study enrollment and were scheduled to engage in an unaided quit attempt. Study inclusion criteria included: (1) being between 18 and 65 years of age; (2) being a regular daily smoker for at least 1 year; (3) smoking an average of at least 8 cigarettes per day (verified via expired carbon monoxide [CO] breath analysis; ≥8 ppm); (4) reporting motivation to quit smoking of at least 5 on a 0–10 point scale; (5) being interested in making a serious unaided quit attempt; and (6) not having decreased the number of daily cigarettes smoked by more than half in the past 6 months. Participants were excluded from the study based on evidence of: (1) limited mental competency (not oriented to person, place, and/or time) and the inability to give informed, voluntary, written consent to participate; (2) pregnancy or the possibility of being pregnant (by self-report); (3) current use of nicotine replacement therapy and/or smoking cessation counseling; (4) current or past history of psychotic-spectrum symptoms or disorders; (5) current substance dependence (excluding nicotine dependence); (6) active suicidality; and, (7) any current use of psychotropic medication, taken as needed.

Of the 84 eligible persons, 26 did not attend their scheduled quit-day appointment. An additional four participants were excluded from the analyses due to equipment malfunction and/or participants’ failure to return the PDA device. Thus, the final sample was comprised of 54 participants (33.3% female; Mage = 34.6, SD = 13.8). The racial composition was 86.3% white, 7.8% black or African American, 3.9% “mixed,” and 2.0% Asian. In terms of smoking characteristics, participants reported smoking their first cigarette at 14.6 ( SD = 2.8) years of age and being a daily smoker for 15.4 years ( SD = 12.9). Participants reported smoking an average of 15.9 ( SD = 10.2) cigarettes per day upon study entry, and endorsed an average of 3.2 on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, 24 indicating low-moderate levels of nicotine dependence. Regarding prior cessation behavior, participants endorsed an average of 3.2 past “serious” quit attempts ( SD = 2.5).

As assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders-Non-Patient Version (SCID-I/NP 25 ), 35.3% of the sample met criteria for current (past month) Axis I psychopathology. Approximately 41.0% of the sample endorsed drinking alcohol at least 2–3 times per week. In terms of hazardous drinking, 36.1% of male participants scored at least 9 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT 26 ), while 33.3% of female participants endorsed at least 8 on the AUDIT. Approximately 56.0% of the sample endorsed some level of marijuana use within the past 30 days.

Measures

Screening and Descriptive Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Non-Patient Version

Diagnostic exclusions and prevalence/incidence of current (past month) Axis I diagnoses were assessed via the SCID-I/NP. 25 The SCID-I/NP follows the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) diagnosis guidelines and demonstrates good psychometric properties. 27 , 28 Interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of 10% of interviews was checked for accuracy.

Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire

The Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire is a self-report instrument that includes items pertaining to both lifetime and past 30-day marijuana smoking rate, age of onset at initiation, years of being a regular marijuana smoker, and other descriptive information (eg, number of attempts to discontinue using marijuana). 29

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

The AUDIT, developed by the World Health Organization, was employed to assess frequency of alcohol consumption and alcohol use problems. 26 The AUDIT has evidenced excellent psychometric properties in past work. 30 Internal consistency was adequate in the present sample (α = .83).

Smoking History Questionnaire

The Smoking History Questionnaire is a self-report measure used to collect descriptive information regarding smoking history (eg, onset of regular smoking), pattern (eg, number of cigarettes consumed per day), past quit attempts (eg, how many times in your life have you made a serious quit attempt), and problematic symptoms experienced during quitting (eg, weight gain, nausea, irritability, and anxiety. 31 , 32

Motivation to Quit Smoking

The Motivation to Quit Smoking measure is based on the stages of change research conducted by Prochaska and colleagues to determine a participant’s pre-cessation motivation to quit smoking. 33 This measure was used for screening and participant selection purposes. Specifically, participants were required to endorse at least a 5 on a 0–10 point scale, indicating serious interest in quitting smoking (“I often think about quitting smoking, but have no plans to quit”).

Primary Measures

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) is a six-item scale designed to assess gradations in tobacco dependence. 25 The FTND is a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ 34 ). Although the FTND has demonstrated questionable psychometric properties, including poor internal consistency, 35–37 it remains one of the most commonly used measures of nicotine dependence. Consistent with this account, internal consistency of the FTND in the current sample was α = .51.

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3) is an 18-item self-report measure which assesses sensitivity to, and discomfort with, physical sensations. 38 Participants are instructed to rate the degree to which they believe the 18 statements apply to them (eg, “It scares me when my heart beats rapidly”) on a Likert-type scale from 0 (“very little”) to 4 (“very much”). The ASI-3 was developed to improve upon the factor structure of the original 16-item ASI. 2 The ASI-3 has been psychometrically-validated for use among daily cigarette smokers. 39 Research has noted that when utilizing a continuous measurement of AS, it is optimally derived from the combined scores on the physical and cognitive subscales, while omitting the items related to the social subscale. 40 Thus, the present investigation utilized a composite score derived from these two subscales (physical and cognitive). Internal consistency of ASI-3 (combined score of the physical and cognitive subscales) in the current sample was α = 0.91.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule

In the present study, state-level negative mood was assessed prequit and postquit using the well-established 20-item PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule). 41 The negative affect subscale (N-PANAS) consists of 10-items, and assesses general dimensions of negative affectivity (eg, distressed; ashamed). In the present investigation, the time-referent of the PANAS was changed from generally to currently in order to capture state-level, as opposed to trait-level, negative affect. Specifically, participants were provided with the following prompt: “please indicate to what extent you are currently feeling [upset, nervous, etc.].” Two indices of negative affect were utilized: (1) prequit negative affect and (2) negative affect experienced during the cessation attempt. First, participants completed daily ratings of the PANAS via online surveys at the end of each day for 3 days prior to their scheduled quit day (prequit negative affect). Prequit negative affect was measured by calculating an average score across the 3 days prior to quit day. Second, negative affect, as it occurred in the context of the cessation attempt, was measured via EMA procedures (3× per day for 14 days). Each emotion was rated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely). The PANAS is a well-established index with sound psychometric properties. 41 Internal consistency of the N-PANAS items in the current sample at baseline was α = 0.85.

Daily Smoking Behavior Status

Self-reports of smoking status were collected from participants via EMA procedures (3× per day for 14 days). Specifically, at each prompt, participants were asked “Have you smoked any cigarettes since the last time you completed questions on the handheld?” Reports of abstinence were verified by expired CO breath sample (8 ppm cutoff) at in-person follow-up assessment points (quit day, 3, 7, 14). Expired air CO levels were assessed with a Vitalograph Breathco CO monitor. 42 Detected values above the stated cutoff scores were considered indicative of smoking.

Ecological Momentary Assessment

Participants completed daily assessments away from the laboratory, in their regular daily environments, for the first 14 days of their cessation attempt using a pocket PC mini-computer (palm-sized device) utilized in past smoking research. 23 Each palm pilot handheld was preprogrammed to administer the selected self-report measures, over the course of the first 14 days of the cessation attempt, at three random intervals during the day, each day (between 10:00 AM and 7:00 PM). Using the EMA handheld mini-computer, daily smoking status (smoked since last recording) and state-level (that day) negative affect (N-PANAS) were assessed.

Apparatus

Throughout the initial 14 days of the quit attempt, participants were instructed to carry with them the Palm Z22 Handheld PDA. Each palm pilot was programmed with the Experience Sampling Program, Version 4.0. 43 Experience Sampling Program is an open-source software package designed to administer questionnaires, surveys, or experiments via a palm pilot or compatible handheld computer. Experience Sampling Program allows the researcher to create a predetermined schedule of assessment, prompting participants to answer and record their responses using the palm pilot device. Participants responses were recorded and stored on the palm pilot device throughout the duration of the study (eg, initial 14 days of cessation), and were later accessible to download onto a computer for analysis.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from two sites—University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, United States (86.3%) and University of Houston, Houston, Texas, United States (13.7%)—at which identical procedures were executed. Individuals who responded to advertisements for a research study on “quitting smoking” were scheduled for an in-person session to determine eligibility and collect baseline data. The current study was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. As such, upon arrival at the laboratory, participants provided informed consent and were administered the SCID-I/NP by a trained graduate student. Participants biochemically verified their smoking status by CO analysis of breath samples (≥8 ppm 44 ). Participants also completed a packet of self-report questionnaires (including the ASI-3). All participants were compensated $20 for participating in the baseline session. Eligible participants were then invited to complete an unaided quit attempt. Of note, participants were instructed to quit smoking on their own, without any assistance (ie, absent of pharmacological or psychosocial treatment). Additionally, participants were compensated for completing in-person assessments; however, they were not incentivized to remain abstinent.

On the participant-designated quit day, participants were scheduled to come back to the laboratory to biochemically verify smoking abstinence and at this point also received the handheld palm pilot. All participants were permitted to engage in the 14-day assessment period, regardless of their smoking status. Participants endorsing smoking on quit day were informed that they may continue to initiate quitting within the assessment period. They were given a standardized orientation to the ambulatory assessment component of the study, instructed in the care and use of the equipment, and shown how to respond to questions posed on the pocket PC minicomputer’s display. Participants were asked to carry the palm pilot device with them at all times between the hours of 10:00 AM and 7:00 PM for 2 weeks to ensure consistency of responding. They were also scheduled to attend in-person follow-up assessments at days 3, 7, and 14 postquit to verify abstinence. On days 3 and 7 postquit abstinence was verified via CO analysis of breath samples; on day 14 postquit abstinence was verified by both CO analysis of breath samples as well as collection of saliva cotinine. Participants were compensated an additional $10 for completion of each of the follow-up assessments.

A total of 42 repeated EMA assessments were administered across the initial 14 days of the quit attempt. For each participant, within-day EMA entries were binned and averaged to derive a total of 14 daily ratings of negative affect. Smoking status was determined based upon participants’ endorsement of abstinence across all entries on a given day (coded 0 = abstinent) or having one or more indication of smoking on a given day (coded 1 = smoking). EMA entries were completed on an average of 10.2 days ( SD = 3.2); the average number of EMA entries completed per day was 1.4 ( SD = 0.35).

Data Analytic Strategy

The continuous Level-1 predictor (daily rating of negative affect) was centered within-person, such that the score on a given day reflected the daily deviation from the participant’s overall average daily rating. This approach was applied to remove between-person variance. Time was centered at quit day (range 0–13 days). Grand mean centering was conducted for continuous Level-2 predictors (AS and covariates) to improve interpretability of coefficients.

To test the primary study aims, a multi-level mixed model analytic approach was used. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Specifically, PROC MIXED was used to construct Models 1 and 2 and PROC GLIMMIX was used for Model 3 (to account for the binary outcome variable). In Model 1, a multi-level mixed model was constructed to include the main effect of AS (time-invariant predictor), time, and their interaction in predicting negative affect during the quit period. We specified a random slope for time, such that the slope was allowed to vary by participant; furthermore, we specified the repeated statement for the association between time-points (the residual correlations across days) as autoregressive. In Model 2, a multi-level mixed model was constructed to examine the main effect of AS, daily smoking status during the quit period (time-varying), and their interaction to predict same-day changes in negative affect. As before, we specified a random intercept and an autoregressive covariance matrix for time. In both Models 1 and 2, prequit levels of negative affect (averaged across the 3 days prior to quit day) were tested as a time-invariant covariate to control for baseline levels of the outcome prior to engaging in the quit attempt. In Model 3, the effect of AS, between-day change in negative affect during the quit period, and their interaction were tested as predictors of self-reported daily smoking status (per EMA) during the 14 days postquit. We specified a random statement for the intercept, as well as a repeated statement with an autoregressive covariance matrix for time. In all analyses, we specified Satterthwaite degrees of freedom for the denominator.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Lapse Behavior

First, inter-correlations between the study variables were examined. Specifically, for each participant, aggregate variables for daily change in negative affect and smoking status across the EMA assessment period was computed; these aggregate variables were correlated with the remaining Level-2 variables (AS, nicotine dependence and prequit negative affect). Correlations, as well as means and standard deviations, are reported in Table 1 . There was a significant and positive association between the person-average daily change in negative affect and AS, and between person-average daily change in negative affect and prequit negative affect. There was also a significant positive association between AS and prequit negative affect. No other significant associations were observed.

Table 1.

Means and Correlations for All Study Variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Daily PANAS | 16.12 | 5.21 | 0.68**** | |||

| 2.Daily smoking status | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.59**** | ||

| 3.AS | 7.15 | 8.34 | 0.51**** | 0.02 | — | |

| 4.FTND | 3.20 | 1.76 | 0.25* | 0.08 | 0.09 | — |

| 5.Prequit PANAS | 16.69 | 6.03 | 0.80**** | 0.13 | 0.50**** | 0.23* |

EMA = Ecological Momentary Assessment; FTND = Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; High-risk AS = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (cognitive and physical concerns subscales); Prequit PANAS = average (time-invariant) Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Negative Affect; Daily PANAS (daily ratings of negative affect per EMA); Daily smoking status (1 = smoking, 0 = no smoking). The values on the diagonal in italic bold reflect the ICC for the empty model; it indicates the amount of variance due to the nest structure (between-person variance).

* P < .1; ** P ≤ .05; *** P ≤ .01; **** P < .001.

Lapse rates were highest during the early phase of the quit attempt and slow thereafter. Specifically, 30% of the participants were unable to abstain on their designated quit day; 63% of the participants lapsed into smoking within the first 3 days of their quit date; 75% of the participants had lapsed by the seventh day postquit; and 78% of the participants had lapsed by the 14th day postquit. The average number of days to first smoking lapse within the sample was 6.8.

Interaction Analyses

Results from Model 1 are presented in Table 2 . Results indicated a significant effect of AS in terms of quit-day negative affect (intercept; b = 0.17, P = .007), after controlling for prequit negative affect ( b = 0.56, P < .001) and the nonsignificant effect of prequit nicotine dependence. There was a nonsignificant effect of time, suggesting that levels of negative affect did not significantly change during the 14 days postquit. Additionally, there was a nonsignificant interaction of AS × time, indicating that changes in negative affect across the quit period did not differ as a function of level of AS.

Table 2.

Fixed Effects Estimates

| Model 1 | Negative affect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect | Estimate | SE | t | Sig | ||

| Intercept | 16.36 | 0.45 | 36.41 | <.001 | ||

| FTND | 0.36 | 0.25 | 1.48 | .15 | ||

| Prequit PANAS | 0.56 | 0.08 | 6.76 | <.001 | ||

| AS | 0.17 | 0.06 | 2.77 | .01 | ||

| Time | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.66 | .51 | ||

| AS × time | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.70 | .10 | ||

| Model 2 | Negative affect | |||||

| Fixed effect | Estimate | SE | t | Sig | ||

| Intercept | 16.52 | 0.49 | 34.02 | <.001 | ||

| FTND | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.77 | .45 | ||

| Prequit PANAS | 0.60 | 0.09 | 6.86 | <.001 | ||

| AS | 0.17 | 0.07 | 2.54 | .01 | ||

| Daily smoking status | 0.77 | 0.44 | −1.75 | .08 | ||

| AS × smoking | 0.15 | 0.05 | −2.77 | .01 | ||

| Model 3 | Same-day smoking status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect | Estimate | SE | t | Sig | OR | OR 95% CI |

| Intercept | 0.17 | .34 | 0.50 | .62 | 1.18 | 0.61, 2.30 |

| FTND | −0.001 | .20 | −0.01 | .10 | 1.00 | 0.68, 1.47 |

| Prequit PANAS | 0.06 | .07 | 0.86 | .40 | 1.06 | 0.93, 1.21 |

| AS | −0.01 | .05 | −0.27 | .79 | 0.99 | 0.90, 1.08 |

| Daily PANAS | 0.06 | .03 | 1.92 | .06 | 1.06 | 1.00, 1.13 |

| AS × daily PANAS | 0.01 | .004 | 2.29 | .02 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 |

CI = confidence interval; EMA = Ecological Momentary Assessment; FTND = Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; High Risk AS = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (cognitive and physical concerns subscales); OR = odds ratio; Prequit PANAS = average (time-invariant) Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Negative Affect; SE = standard error; Daily smoking status (1 = smoking, 0 = no smoking); Daily PANAS (daily ratings of negative affect per EMA).

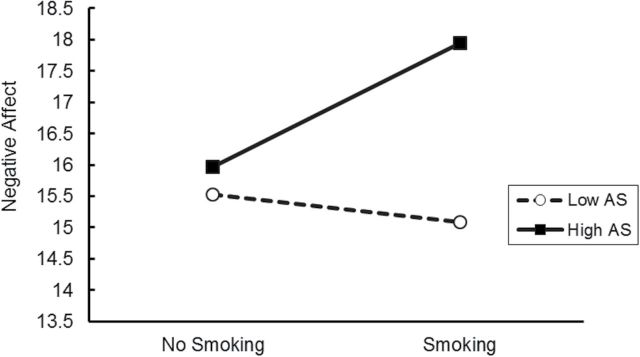

With regard to Model 2, the fixed effects estimates are presented in Table 2 . A significant effect of AS on the intercept was observed, such that AS was positively associated with greater average negative affect experienced throughout the quit attempt ( b = 0.17, P = .014). This effect was significant after controlling for the effect of prequit negative affect ( b = 0.60, P < .001) and the nonsignificant effect of nicotine dependence. There was a nonsignificant (although trending) effect of smoking on a given day in predicting negative affect experienced that same day ( b = 0.77, P = .08). These main effects were qualified by a significant interaction of AS and daily smoking status in predicting negative affect ( b = 0.15, P = .006). The form of the interaction is presented in Figure 1 . Specifically, results indicated that participants characterized by high levels of AS reported significant increases in same-day negative affect on days when they endorsed smoking, relative to days they endorsed abstinence ( b = 0.98, P = .03). The association between smoking status and negative affect was nonsignificant for participants characterized by low levels of AS ( b = −0.33, P = ns).

Figure 1.

Interaction of anxiety sensitivity (AS) by smoking status to predict increases in between-day change in negative affect.

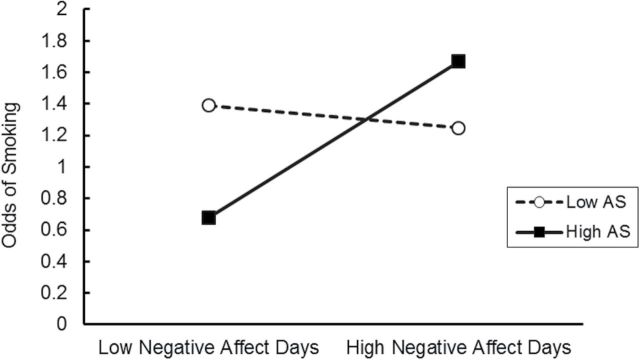

For Model 3, Table 2 provides the estimates for the likelihood of smoking as a function of AS and between-day change in negative affect. Results indicated that no prequit factors significantly predicted likelihood of smoking on any given day postquit attempt, including prequit negative affect, nicotine dependence, or AS. There was a trend-effect of between-day change in negative affect in terms of smoking likelihood, such that on days when smokers experienced (within-person) increases in negative affect during the cessation period, they were at an increased likelihood of smoking ( b = 0.06, P = .055). These main effects were qualified by a significant interaction of AS and between-day change in negative affect in predicting same-day smoking incidence ( b = 0.009, P = .023). The form of this interaction is presented in Figure 2 . Specifically, plots of the simple slopes indicated that participants characterized by high levels of AS were at a significantly higher risk of smoking on days when negative affect is high relative to low ( b = 0.14, P = .004). The same effect was nonsignificant for participants characterized by low levels of AS ( b = −0.02, P = ns).

Figure 2.

Interaction of anxiety sensitivity (AS) by between-day change in negative affect to predict likelihood of smoking.

Discussion

The present study sought to examine the dynamic interplay between AS, negative affect, and smoking behavior during the course of a self-guided (unaided) quit attempt. In terms of the main effects of AS and daily smoking lapse behavior in relation to change in negative affect during the quit attempt, several key findings were observed. First, AS was significantly associated with greater overall levels of negative affect experienced throughout the 14 days of the quit attempt. Here, high AS smokers endorsed more severe and distressing negative affect across the initial 14 days of cessation as compared to their low AS counterparts. Yet, smoking status (relative to abstinence) was not a unique predictor of overall levels of negative affect during the quit attempt. Notably, results indicated a significant interaction between AS and daily smoking lapse behavior in terms of between-day change in negative affect. Contrary to prediction, participants characterized by high levels of AS reported significant increases in same-day negative affect on days when they endorsed smoking, relative to days they endorsed abstinence. This association was nonsignificant for participants characterized by low levels of AS. A possible explanation for this finding may be that among high AS smokers, a forward-feeding cycle may develop, whereby smoking is used as a coping strategy for managing negative mood states in the short term, yet paradoxically confers risk for greater negative affective experiences over time. Specifically, individuals high in AS may experience greater degrees of negative affect during early periods of abstinence as well as in response to smoking lapses during cessation, which may in turn, promote a faster progression to relapse.

When examining the main effects of AS and between-day change in negative affect in relation to smoking lapse behavior, results revealed that neither AS nor negative affect independently influenced the likelihood of smoking during the cessation attempt. However, a significant interaction was observed such that participants characterized by high levels of AS were at a higher risk of smoking on days when negative affect was high (relative to low). This effect was nonsignificant for participants characterized by low levels of AS. This pattern of findings is consistent with previous empirical work demonstrating that smokers high in AS experience greater exacerbations of negative mood states, such as anxiety and/or depression, during the early phases of quitting. 19 Moreover, our results lend further support to theoretical models purporting that smokers high in AS may encounter greater difficulty with smoking cessation due to their perception that these internal states are personally harmful and threatening. 1 , 45 , 46

These findings underscore that AS may serve as a putative mechanism involved in early smoking cessation lapse and exacerbation of negative affect during a quit attempt. Specifically, smokers characterized by high levels of AS may be more apt to experience, and negatively respond to, greater affective disturbance during episodes of abstinence. Given that high AS individuals hold stronger expectations of the affect-regulating properties of smoking, 45 , 47 this subgroup of smokers may be more motivated to re-engage in smoking (lapse) to counteract the abstinence-provoked states of negative affect. The current findings also suggest that high AS individuals may be at greater risk for progression from lapse to full-blown relapse given that this subgroup of smokers endorsed greater negative affect on days when they smoked, relative to days they remained abstinent.

Together, these findings point to AS as a potentially important factor to target in smoking cessation, as it appears to uniquely impact the subjective experience of negative affect and lapse behavior. Existing AS reduction programs for smoking cessation, albeit still in developmental phases, have provided evidence of the feasibility and merit of incorporating tailored cognitive-behavioral skills that specifically address affective vulnerabilities (eg, interoceptive exposure, psychoeducation) into smoking cessation programs. 48 Consistent with such work, the present findings suggest that it may be advisable to modify levels of AS prior to initiating a quit attempt in order to reduce negative affect states experienced during acute periods of abstinence.

A number of limitations of the present investigation and points for future direction should be considered. First, participants volunteered to participate in an unaided quit attempt (ie, no psychosocial or pharmacological treatment was provided) for monetary compensation. Therefore, it is unclear whether these results will generalize to smokers receiving formal cessation treatment. Replication of these findings in a treatment-seeking sample may be an important next step. Second, our sample was largely comprised of a relatively homogenous group of smokers (~87% white). To increase the generalizability/representativeness of these findings, it will be important for future studies to recruit a more ethnically/racially diverse sample of smokers. Third, the smokers participating in the current study endorsed low-moderate levels of nicotine dependence. It, therefore, may be beneficial for future studies to sample smokers with varying levels of nicotine dependence to ensure the generalizability of the results to the general smoking population. Fourth, AS was only measured at baseline. Although AS is conceptualized as a trait-like cognitive characteristic, evidence suggests that it is malleable, and may change in response to cognitive-behavioral cessation interventions. 8 However, less is known about whether levels of AS vary as a direct function of smoking cessation (in the absence of psychosocial treatment). Thus, future research may benefit from assessing changes in AS overtime in relation to smoking cessation outcomes among self-quitters. Fifth, in the current study, EMA compliance was relatively low, producing large amounts of missing data. Specific statistical procedures were utilized in an attempt to minimize the effects of missing data; however, it remains unclear how the low level of compliance impacted the overall pattern of results. Sixth, although negative affect and lapse behavior were assessed prospectively over time, given study procedures, and missing data, we were unable to definitely evaluate the temporal ordering of these variables. Thus, future work may benefit from a more stringent assessment of negative affect and smoking behavior in order to accurately capture proximal associations over time. Finally, there is a high degree of overlap between negative affect and nicotine withdrawal symptoms. The current investigation was interested in exploring the role of negative affect, specifically, in terms of the relations between AS and smoking behavior during cessation. Yet, it may be fruitful for future studies to expand the focus to the withdrawal syndrome more broadly in order to more fully capture factors that influence cessation difficulties.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant F31-DA026634 awarded to KJL by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This work was also supported by grant R01-MH076629-01A1 awarded to MJZ by the National Institute of Mental Health and F31-DA035564-02 awarded to SGF by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Please note that the content presented does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and that the funding sources had no other role other than financial support.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ . Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity . Psychol Bull . 2014. ; 141 ( 1 ): 176 – 212 . doi: 10.1037/bul0000003 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ . Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness . Behav Res Ther . 1986. ; 24 ( 1 ): 1 – 8 . doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smits JAJ, Berry AC, Tart CD, Powers MB . The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions for reducing anxiety sensitivity: a meta-analytic review . Behav Res Ther . 2008. ; 46 ( 9 ): 1047 – 1054 . doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rapee RM, Medoro L . Fear of physical sensations and trait anxiety as mediators of the response to hyperventilation in nonclinical subjects . J Abnorm Psychol . 1994. ; 103 ( 4 ): 693 – 693 . doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battista SR, Stewart SH, Fulton HG, Steeves D, Darredeau C, Gavric D . A further investigation of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to smoking motives . Addict Behav . 2008. ; 33 ( 11 ): 1402 – 1408 . doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson KA, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Smits JAJ, Zvolensky MJ . Panic attack history and anxiety sensitivity in relation to cognitive-based smoking processes among treatment-seeking daily smokers . Nicotine Tob Res . 2013. ; 15 ( 1 ): 1 – 10 . doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr332 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE . Anxiety sensitivity: relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder . Addict Behav . 2001. ; 26 ( 1 ): 887 – 899 . doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00241-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Assayag Y, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Steeves D, Stewart SS . Nature and role of change in anxiety sensitivity during NRT-aided cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation treatment . Cogn Behav Ther . 2012. ; 41 ( 1 ): 51 – 62 . doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.632437 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Leventhal AM, Schmidt NB . Anxiety sensitivity mediates relations between emotional disorders and smoking . Psychol Addict Behav . 2014. ; 28 ( 3 ): 912 – 920 . doi: 10.1037/a0037450 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC . Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement . Psychol Rev . 2004. ; 111 ( 1 ): 33 – 51 . doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.1.33 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB . Life before and after quitting smoking: an electronic diary study . J Abnorm Psychol . 2006. ; 115 ( 3 ): 385 – 396 . doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.115.3.454 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piasecki TM, Niaura R, Shadel WG, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics in unaided quitters . J Abnorm Psychol . 2000. ; 109 ( 1 ): 74 – 86 . doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.74 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, Jorenby DE, Baker TB . Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment . Addict . 2011. ; 106 ( 2 ): 418 – 427 . doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03173.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilbert DG, Meliska CJ, Williams CL, Jensen RA . Subjective correlates of cigarette-smoking-induced elevations of peripheral beta-endorphin and cortisol . Psychopharmacol . 1992. ; 106 ( 2 ): 275 – 281 . doi: 10.1007/bf02801984 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shiffman S, Waters AJ . Negative affect and smoking lapses: a prospective analysis . J Consult Clin Psychol . 2004. ; 72 : 192 – 201 . doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.2.192 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beckham JC, Dennis MF, McClernon FJ, et al. The effects of cigarette smoking on script-driven imagery in smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder . Addict Behav . 2007. ; 32 ( 12 ): 2900 – 2915 . doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.026 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carter BL, Lam CY, Robinson JD, et al. Real-time craving and mood assessments before and after smoking . Nicotine Tob Res . 2007. ; 10 ( 7 ): 1165 – 1169 . doi: 10.1080/14622200802163084 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Giedgowd GE, Concklin CA, Sayette MA . Differences in negative mood-induced smoking reinforcement due to distress tolerance, anxiety sensitivity, and depression history . Psychopharmacol . 2010. ; 210 ( 1 ): 25 – 34 . doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1811-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Langdon KJ, Leventhal AM, Stewart S, Rosenfield D, Steeves D, Zvolensky MJ . Anhedonia and anxiety sensitivity: prospective relationships to nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation . J Stud Alcohol Drugs . 2013. ; 74 ( 3 ): 469 . doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.469 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong M, Krajisnik A, Truong L, et al. Anxiety sensitivity as a predictor of acute subjective effects of smoking . Nicotine Tob Res . 2012. ; 15 ( 6 ): 1084 – 1090 . doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts208 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evatt DP, Kassel JD . Smoking, arousal, and affect: the role of anxiety sensitivity . J Anxiety Disord . 2010. ; 24 ( 1 ): 114 – 123 . doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shiffman S . Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use . Psychol Assess . 2009. ; 21 ( 4 ): 486 – 497 . doi: 10.1037/a0017074 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickox M . First lapses to smoking: within-subjects analysis of real-time reports . J Consult Clin Psychol . 1996. ; 64 ( 2 ): 366 – 379 . doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.64.2.366 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO . The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire . Brit J Addict . 1991. ; 86 ( 9 ): 1119 – 1127 . doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J . Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) . New York, NY: : Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; ; 2002. . [Google Scholar]

- 26. Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M . AUDIT- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care . Geneva, Switzerland: : World Health Organization; ; 1992. . [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A . Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II) . Clin Psychol Psychother . 2011. ; 18 ( 1 ): 75 – 79 . doi: 10.1002/cpp.693 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shear MK, Greeno C, Kang J, et al. . Diagnosis of nonpsychotic patients in community clinics . Am J Psychiatr . 2000. ; 157 ( 4 ): 581 – 587 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ . The Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire . Burlington, VT: The Anxiety and Health Research Laboratory, University of Vermont; ; 2005. . Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M . Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II . Addict . 1993. ; 88 ( 6 ): 791 – 804 . doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR . Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts . J Abnorm Psychol . 2002. ; 111 ( 1 ): 180 – 185 . doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.111.1.180 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA . Nonclinical panic attack history and smoking cessation: an initial examination . Addict Behav . 2004. ; 29 ( 4 ): 825 – 830 . doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rundmo T, Smedslund G, Gotestam KG . Motivation for smoking cessation among the Norwegian public . Addict Behav . 1997. ; 22 ( 3 ): 377 – 386 . doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00056-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fagerström K . Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment . Addict Behav . 1978. ; 3 ( 3–4 ): 235 – 241 . doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burling AS, Burling TA . A comparison of self-report measures of nicotine dependence among male drug/alcohol-dependent cigarette smokers . Nicotine Tob Res . 2003. ; 5 ( 5 ): 625 – 633 . doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158708 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sledjeski EM, Dierker LC, Costello D, et al. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample . Drug Alcohol Depend . 2007. ; 87 ( 1 ): 10 – 19 . doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Steinberg ML, Williams JM, Steinberg HR, Krejci JA, Ziedonis DM . Applicability of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in smokers with schizophrenia . Addict Behav . 2005. ; 30 ( 1 ): 49 – 59 . doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, et al. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 . Psychol Assess . 2007. ; 19 ( 2 ): 176 – 188 . doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farris SG, DiBello AM, Allan NP, Hogan J, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ . Evaluation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 among treatment-seeking smokers . Psychol Assess . In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernstein A, Stickle TR, Zvolensky MJ, Taylor S, Abramowitz J, Stewart S . Dimensional, categorical, or dimensional-categories: testing the latent structure of anxiety sensitivity among adults using Factor-Mixture Modeling . Behavior Therapy . 2010. ; 41 ( 4 ): 515 – 529 . doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.02.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A . Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales . J Pers Soc Psychol . 1988. ; 54 ( 6 ): 1063 – 1070 . doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jarvis MJ, Hajek P, Russell MA, et al. Nasal nicotine solution as an aid to cigarette withdrawal: a pilot clinical trial . Brit J Addict . 1987. ; 82 ( 9 ): 983 – 988 . doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01558.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barrett LF, Barrett DJ . An introduction to computerized experience sampling in psychology . Soc Sci Comput Rev . 2001. ; 19 : 2 . [Google Scholar]

- 44. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Research Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification . Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res . 2002;4(2):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45. Farris SG, Langdon KJ, DiBello AM, Zvolensky MJ . Why do anxiety sensitive smokers perceive quitting as difficult?: the role of expecting “interoceptive threat” during acute abstinence . Cognit Ther Res . 2014. ; 39 ( 2 ): 236 – 244 . doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9644-6 . [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A . Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2005. ; 14 ( 6 ): 301 – 305 . doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00386.x . [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abrams K, Zvolensky MJ, Dorman L, Gonzalez A, Mayer M . Development and validation of the Smoking Abstinence Expectancies Questionnaire . Nicotine Tob Res . 2011. ; 13 ( 12 ): 1296 – 1304 . doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr184 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zvolensky M, Yartz A, Gregor K, Gonzalez A, Bernstein A . Interoceptive exposure-based cessation intervention for smokers high in anxiety sensitivity: a case series . J Cogn Psychother . 2008. ; 22 ( 4 ): 346 – 365 . doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.22.4.346 . [Google Scholar]