Abstract

Virulence factor activity relationships (VFARs) – a concept loosely based on quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSARs) for chemicals was proposed as a predictive tool for ranking risks due to microorganisms relevant to water safety. A rapid increase in sequencing capabilities and bioinformatics tools has significantly increased the potential for VFAR-based analyses. This review summarizes more than 20 bioinformatics databases and tools, developed over the last decade, along with their virulence and antimicrobial resistance prediction capabilities. With the number of bacterial whole genome sequences exceeding 241 000 and metagenomic analysis projects exceeding 13 000 and the ability to add additional genome sequences for few hundred dollars, it is evident that further development of VFARs is not limited by the availability of information at least at the genomic level. However, additional information related to co-occurrence, treatment response, modulation of virulence due to environmental and other factors, and economic impact must be gathered and incorporated in a manner that also addresses the associated uncertainties. Of the bioinformatics tools, a majority are either designed exclusively for virulence/resistance determination or equipped with a dedicated module. The remaining have the potential to be employed for evaluating virulence. This review focusing broadly on omics technologies and tools supports the notion that these tools are now sufficiently developed to allow the application of VFAR approaches combined with additional engineering and economic analyses to rank and prioritize organisms important to a given niche. Knowledge gaps do exist but can be filled with focused experimental and theoretical analyses that were unimaginable a decade ago. Further developments should consider the integration of the measurement of activity, risk, and uncertainty to improve the current capabilities.

Introduction

The term “virulence factor activity relationship” (VFAR) refers to the utilization of structure–activity relationships to compare the structures of newly identified or produced virulent factors and associated genes to the known ones for the prediction of their virulence and other functional properties. VFARs were envisioned in 2001 in a National Research Council report,1 around the same time when human genome sequencing was completed and the number of completed and published bacterial genomes was less than 100 to establish predictive capabilities for ranking of risk posed by microorganisms as a tool necessary for regulating waterborne pathogens. Regulations for the microbial safety of water may require implementation of expensive technology; hence, decision-making processes must employ approaches that are quantitative and allow benefit-cost analysis. The overall concept had parallels in quantitative structure–activity relationships – a term used for predicting risk from chemicals coined much earlier in 1962.2 The ability to predict virulence and its severity based on measurements of characteristics coded in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics and their modulatory mechanisms, although complex, is fundamentally sound. It is described as Koch postulates in silico by one researcher.3 The concept was then further discussed in a workshop focused on VFARs.4 Since then, numerous and significant developments have occurred contributing to the capability of predicting virulence and risk from microbial sequences. More often, these developments are based on studies that predate the first VFAR report and do not necessarily use the term – VFAR. In fact, of the more than one hundred publications reviewed here due to their relevance to VFARs, only few5–8 refer to the original National Research Council report.1 This exemplifies that the need for developing the ability to predict functions including virulence based on sequence information is universal and includes scientists engaged in predicting increased risk of infectious diseases due to climate change, clinicians engaged in predicting antimicrobial resistance, and regulatory bodies engaged in ensuring public and ecosystem health, among many others.

Although the first bacterial genome was sequenced more than two decades ago in 1995,9 completion of the first human genome was announced on April 14, 2003. The VFAR concept – coined in 2001, reflected the hope from such information. Since then, incredible progress has been made in the microbial information available using omics technologies. As of February 11, 2017, the Genomes Online Database (GOLD) contained 265 824 organisms (virus, bacteria, fungus, plant or animal); of which, 241 658 are bacteria.10 The number of informatics or sequence analysis projects, a majority of which focus on genomics and metagenomics, also exceeds 105 708. A significant number of microbial community samples for metagenomics also relate to water, wastewater, surface water and other water bodies providing occurrence data.

This progress was to some extent made possible by a significant decrease in the cost of sequencing. While Haemophilus influenza sequencing was finished at the cost of 50 cents per base in 13 months,11,12 and a human genome was sequenced at a staggering cost of US $2.7 billion and 13 years.13 At present, a human genome can be fully sequenced for less than $1000, and the cost of bacterial whole genome sequencing is also much lower in the range of $100 per gigabase. After the initial disruptive approach pioneered by Craig Venter, a big drop in cost – known as “sequencing cost crash” occurred in 2007 due to the entry of Illumina.14 Based on some flagship projects (e.g., the 1000 Genomes Project by the National Human Genome Research Institute and Precision Medicine Initiative by Beijing Genome Institute – China), it is predicted that more than 100 million human genomes will be sequenced by the year 2030, and the cost may further come down to less than $10 per genome.15 In addition to the lower cost, other technologies on the horizon, e.g., quantum sequencing or quantum tunneling will carry out simultaneous sequencing of DNA, RNA, and proteins – a feat that has not been achieved so far.16 Similarly, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics have made significant progress, albeit not at the scale seen for genomics.17,18 This is evident by the significantly lower number of analysis projects (~2088) in the GOLD that is related to transcriptomics and metatranscriptomics. Bacterial proteome studies are a subset of these studies.19 Studies related to metabolomic and lipidomic analyses with a focus on microbes are even fewer as illustrated by the databases available at the Metabolomics Society20 and the Lipidomics Gateway.21

Combined with these wet analyses and data repository capabilities, there has also been tremendous progress in the availability of bioinformatics tools to analyze such data, infer useful information, and develop predictive models at an unprecedented scale. It is now possible to analyze more than 50 000 whole genome sequences to decipher virulence, antimicrobial resistance, and many other functional repertoires of microorganisms.22–24 Databases and tool repositories such as the Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) – an online resource for bioinformatics tools, provide capabilities to analyze genomic and transcriptomic data on a very large scale.

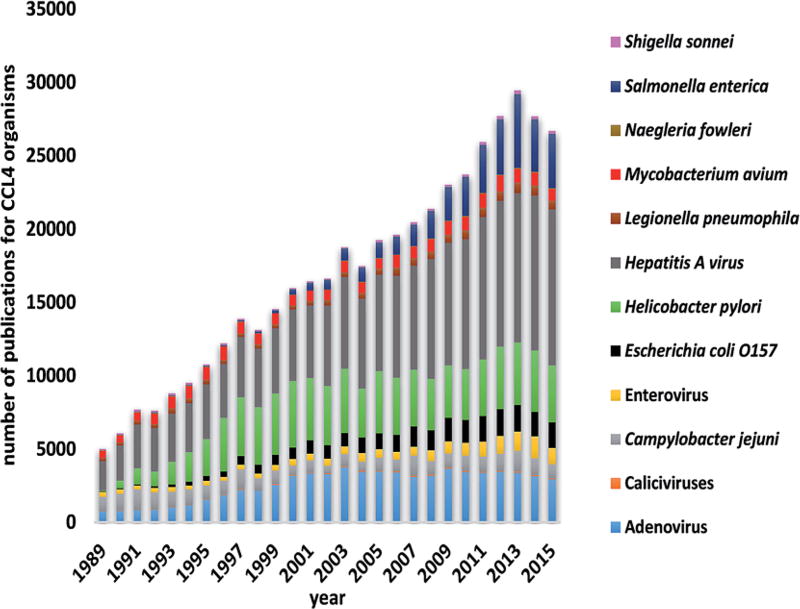

VFARs, as envisioned in the National Research Council report,1 were expected to serve as a tool to select and rank the microbial candidates on the Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List (CCL). The CCL is a mechanism used by the United States Environmental Protection Agency to identify chemical and microbiological hazards that are known or likely to be present in drinking water sources. The presence of such hazards may require preventive measures to protect public health under the Safe Drinking Water Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1974 and most recently amended in 1996. The CCL 4 list announced by the US EPA on November 17, 2016 contains 12 microbial contaminants (assembled in Fig. 1).25 The number of publications available in the Web of Science database that are broadly connected to these 12 microorganisms is also shown in Fig. 1. Considering the VFAR objective of ranking known candidates or determining the suitability of additional candidates to be added to a future CCL, it is evident that the state of science to carry out such an exercise is perhaps adequate with some obvious data gaps that can be easily closed.

Fig. 1.

Number of publications based on Web of Science keyword search of CCL 4 organisms.

This perspective article identifies some of these tools and gaps by providing snapshots of the progress made in omics describing some of the capabilities of selected bioinformatics tools in the context of VFARs. The focus is on the types of capabilities that have been developed so far that could be used to evaluate the VFAR concept rather than carry out a high-resolution analysis of the studies. Examples illustrating the exercise of microbial hazard ranking from other related areas are presented. Finally, a summary of some of the limitations, gaps, and uncertainties associated with such an exercise is also included. Key resources, reviews, and websites are identified for readers who wish to explore some of these tools and resources.

Selected sequence databases and bioinformatics tools relevant to VFARs

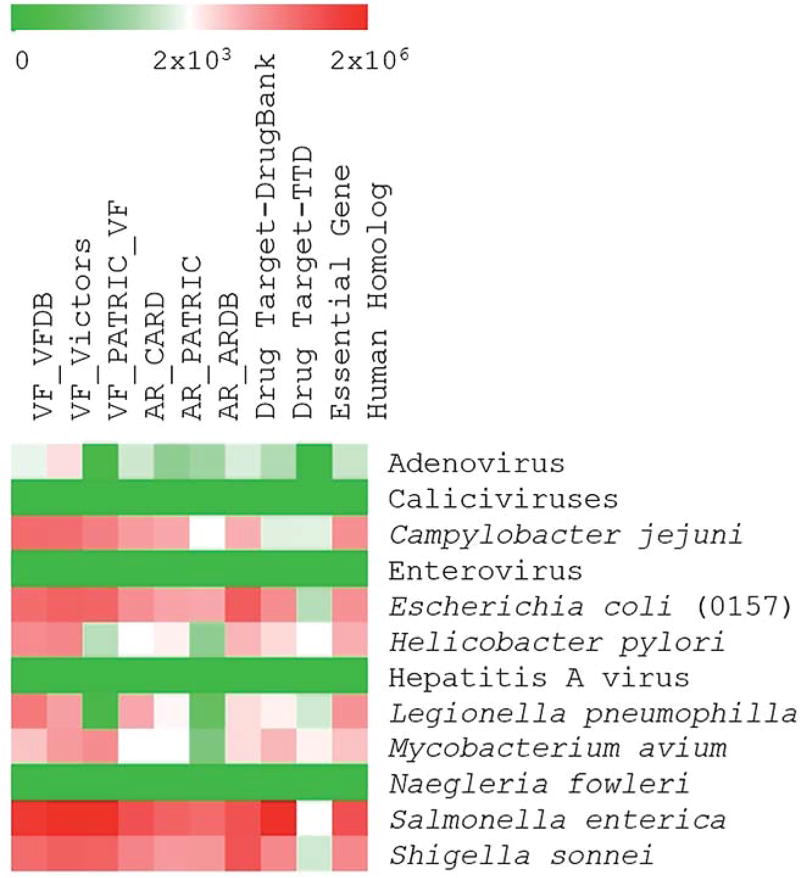

The description of the sequence databases and bioinformatics tools is divided into three categories: databases, genomics tools, and proteomics tools. These resources and approaches are expected to provide an insight into similar exercises carried out in other fields and aid in the analysis of VFARs. The number of sequences in the selected databases as related to the CCL 4 list is shown in Fig. 2. Databases and tools are further summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Number of sequences related to organisms on the CCL 4 list in different databases.

Table 1.

Summary of databases and genomics/proteomics tools

| Name | Distinct feature | Reference data | Input data | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | ||||

| GOLD10 | Can provide metadata information along with the genomes and metagenomes of a large number of organisms | 85 155 whole genome sequences | N.A. | No specific tool for virulence is available in the database |

| IMG 4 (ref. 26) | Able to predict virulence of eukaryotic and viral genomes | 11 568 whole genome sequences | N.A. | No specific tool for virulence is available in the database |

| PATRIC27 | Curation, integration and visualization of virulence factors in the PATRIC database | 22 000 whole genome sequences; 4891 virulent gene sequences | Nucleotide sequences of virulence factors | Data for only six pathogens were integrated for virulence determination |

| VFDB29 | Distribution of virulence factors in distinct categories (secretion systems, toxins etc.); inter-genera virulence factor comparison | 504 whole genome sequences; 2599 virulent gene sequences | Nucleotide or protein sequences | Data redundancy and mixture of experimentally confirmed and predicted virulence factors |

| CARD30 | Curated collection of antibiotic resistance gene sequences equipped with resistance gene identifier (RGI) software for their detection in genome or protein sequences | 2374 resistance gene sequences | Nucleotide or protein sequences | It can only analyse protein sequences and not genome sequences or assembly contigs |

| Genomics tools | ||||

| PICRUSt31 | Prediction of the functional composition of a metagenome on the basis of phylogenetic marker genes | 11 600 general protein information (EC information) | Reference tree; marker genes copy number; functional trait copy number | Accuracy of this tool varies with the depth of the sequencing |

| PAIDB v2.0 (ref. 32) | Can give comprehensive information of reported and potential PAIs and REIs on one platform | 1331 pathogenicity islands; 108 resistance islands | Total ORF of genomes | No integration with other omics platforms for data acquisition and analysis |

| VirulenceFinder33 | Able to detect virulence genes based on WGS data | 76 virulent gene sequences | Pre-assembled, partial or complete genomes | Limited to only three bacterial species |

| Bacterial gene circuits34 | Detection of signature sequences for pathogens and commensals by orthologue abundance | 608 virulent gene sequences; 1364 non-virulent gene sequences | Nucleotide sequences | Incomplete signatures due to incompleteness of many Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway models; no publically available tool is present |

| RVA35 | A technique for the identification of virulent loci using a bacterial genome library | 1536 cosmid sequences | Nucleotide sequences | The technique was performed only with non-virulent recombinant E. coli clones as host strains; no publically available tool is present |

| ARGs-OAP36 | Improved automated classification and enumeration of ARG-like sequences | 4246 resistance gene sequences | Metagenomics data | Repeated annotation evaluation due to continuous inclusion of new ARGs |

| ResFinder39 | Antimicrobial based classification of resistance sequences into various groups | 1400 resistance gene sequences | Pre-assembled, partial or complete genomes | Only predict acquired resistance and unable to predict resistance due to mutations |

| Xander40 | Low memory requirement due to gene targeted metagenomics assembly | Created using other tools using FunGene | Metagenomics read files and reference sequences | Reliance on other software for targeted reference sequences |

| Vikodak43 | Gives detailed information about the functional profiles to infer functional potential of a microbial community based on its 16S rRNA gene analysis in metagenomics data sets | 5876 general protein information (EC information) | Microbial abundance profiles | 16S rRNA gene sequencing data are essential for utilization of the program |

| Protemomics tools | ||||

| MP 3 (ref. 46) | Rapid and accurate detection of pathogenic proteins in large scale genomic & metagenomics reads | 1708 virulent protein sequences; 5815 non-virulent protein sequences | Protein sequences from completed genome or translated metagenomics ORFs | Estimated length of the protein must be known for the metagenomics reads |

| VirulentPred47 | Considerable background noise removal due to two layers of supervised machine learning models in virulent protein predictions | 1025 virulent protein sequences; 1030 non-virulent protein sequences | Single or multiple protein sequences | Poor predictor for eukaryotic virulent proteins |

| VICMpred48 | Functional classification of proteins into virulence factors, information molecules, cellular processes and metabolism molecules | 70 virulent protein sequences; 600 non-virulent protein sequences | Amino acid patterns and composition | Not suitable for multi-functional protein prediction |

| Virulent-Go49 | Gene ontology terms for predicting virulence proteins utilizing single layer machine learning models (support vector models) | 181 virulent protein sequences; 186 non-virulent protein sequences | Protein sequences | GO-term based homology may not occur at all for many proteins; no publicly available tool is present |

| Integrated Query Networks50 | Better prediction of generic and virulent proteins due to multiple queries | 1997 virulent protein sequences; 1703 non-virulent protein sequences | Integrated query graph started with protein sequence query | Prediction accuracy is dependent on choice of data sources and cross linkages |

| PPI networks51 | Prediction of protein functions based on protein–protein interaction networks retrieved from the STRING database | 803 virulent protein sequences | Protein sequences | Reliance on only one database (STRING) may lead to false positive results; no publicly available tool is present |

Databases

Among the microbial sequence databases, foremost is the Genomes Online Database (GOLD).10 It is a comprehensive and centralized repository and data management system for whole genome and metagenome sequencing projects from all over the world. This database also contains curated metadata records – useful for comparative analyses of genomes. The GOLD continuously updates available data from other resources. A user account is required for submission of private data whereas all the publicly available data can be accessed without a user account at http://www.gold.jgi.doe.gov/.

The GOLD also provides a smooth interface with the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) system – another database with a strong focus on gene annotation. The IMG (currently Version 4, hence IMG 4) is a database of genomic information from all three domains of life.26 The GOLD serves as a checkpoint for all the sequencing projects before they are formally passed on to the IMG for annotation of genes. The current version of the IMG provides users with information related to more than 42 million protein-coding genes. By utilizing the comparative genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics tools available with IMG 4, one can infer the functional potential of unannotated virulent genes and predict virulence. The tools are useful for both eukaryotic and viral genomes. However, at present it does not have means to incorporate the effects of environmental and epidemiological factors. It can be accessed at http://www.img.jgi.doe.gov.

Among the databases that focus on specific functional genes repertoires (e.g., virulence, antibiotic resistance, and other factors), the Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) is one of the most comprehensive web resources.27 It contains an extensive set of tools and provides mechanisms to connect to other databases for the required analyses. One of the modules focuses on virulence factors (PATRIC-VF) and displays supporting publications for the identification of genes related to VFs. Through the tools available at the PATRIC-VF, one can access the virulence factors information curated in the Victors database,28 Virulence Factor Database (VFDB),29 and manually curated VFs from six National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-prioritized genera. It can be accessed at http://www.patricbrc.org.

The VFDB mentioned above is an online repository of the virulence factors of bacterial pathogens.29 This database is exclusively used for the bioinformatics mining of the VF related data. In addition to sequence information, the VFDB also provides the structural and functional features of the virulence factors. The VFDB comprises two kinds of datasets – one core set of experimentally verified VF sequences and the other containing information on both verified as well as putative VFs. It also has a characteristic analytical feature of inter- and intragenera comparisons to identify virulent genes. It can be accessed at http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/.

Among the functional gene-focused databases, the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)30 is closely related to VFARs. The CARD is a curated collection of 2374 reference sequences, 3620 ontology terms, 902 single nucleotide polymorphisms, and 2300 antimicrobial resistance gene detection models. Two analytical tools – BLAST and resistance gene identifier, with the ability to predict the resistance in unannotated sequences based on homology and single nucleotide polymorphisms models are also available. It integrates the data of known antimicrobial resistance determinants and their associated phenotypes and provides a framework to organize the antibiotic resistance sequences and other related data by antibiotic resistance ontology. It can be accessed at http://www.arpcard.mcmaster.ca.

Genomics tools

Hundreds of genomics tools are now available that allow analysis of phylogeny and functions including virulence based on sequence information of an isolate or metagenome. High throughput sequencing using universal bacterial primers for the 16S rRNA gene is the most common and economical approach to analyse the phylogenetic diversity of mixed microbial communities. Hence some bioinformatics tools have attempted to predict the community function based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence information (e.g., PICRUSt).31 Other tools are more specifically designed to predict pathogenicity islands, antimicrobial resistance, mobility potential of resistance genes, and other functions specific to virulence and other related characteristics. A few of these tools relevant to VFAR development are described below in more detail. For additional tools, bioinformatics resource portals such as ExPASy are a good starting point (http://www.expasy.org/).

The Pathogenicity Island Database (PAIDB) is a platform dedicated to information about putative and reported pathogenicity islands (PAIs).32 Its modified version is expanded to contain the information about resistance islands (REIs). The Genbank accession numbers of PAIs and REIs were manually collected and 223 types of PAIs and 88 types of REIs were identified. The genomes of 1226 virulent and 1377 non-virulent strains were analysed for the presence of PAIs and REIs. A significant percentage of the candidate PAIs (86%) and candidate REIs (79%) were detected in the genomes of virulent strains but a small portion was also found in the non-pathogenic strains. PAIDB v2.0 is a significant resource because it presents an integrated view of virulence and resistance. The PAIDB can also assist in identifying mechanisms of virulent determinants and help evaluate the virulence potential of commensals. It can be accessed at http://www.paidb.re.kr.

VirulenceFinder – developed using the Center for Genomic Epidemiology web server, is an easy to use tool developed for the identification and extraction of virulent genes from WGS data of E. coli, Enterococcus and S. aureus.33 The predictive performance of VirulenceFinder was evaluated by analysing and comparing 48 WGS samples of verotoxin producing E. coli with routine typing. Results obtained through VirulenceFinder focusing on eae and vtx1 genes agreed with the results obtained by routine typing. VirulenceFinder can also detect other virulent genes missed by routine typing. The tool can be accessed at http://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/VirulenceFinder/.

Bacterial gene circuits is an approach based on a library of gene circuit signatures whose presence or absence in a microbe can potentially define the pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance, or other metabolic pathways.34 Bacterial genomes of 949 pathogenic and 1578 non-pathogenic bacteria from more than 26 genera were used to establish the signature bacterial gene circuits. Gene circuits for pathogens were mostly linked with direct pathogenic mechanisms or signaling pathogenic interactions while most gene circuits for non-pathogens were associated with metabolic pathways. For some of the genera, gene circuitry was established via intra-genus comparisons. The approach has the potential to identify pathogenicity and interactions in more complex systems because of its focus on pathways. The limitations of this approach include: (i) decoded genomes were arbitrarily considered as non-virulent, and (ii) potential incompleteness of the signatures because of their reliance on the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes repository. Despite these limitations, the reported signatures for synergy or pathogenicity seems to be promising for predicting pathogenic phenotypes in isolates or mixed communities.

Many current databases contain genes that lack functional annotation. Rapid virulence annotation solves this problem by identifying the potential loci for virulence in poorly understood pathogens and ascribing biological function to several putative pathogenicity islands.35 This is an assumption-free approach for predicting the virulence factors by using a genomic library of bacteria with multiple invertebrate hosts. The approach was developed by a parallel screening of genomic libraries of the test organism and recombinant clones of E. coli. Gain in toxicity against different invertebrate hosts and subsequent protein analyses were performed to get protein sequences that could be linked to the virulence. During validation with Photorhabdus asymbiotica, the approach could identify 33 virulence factors. Major limitations of the rapid virulence annotation approach are its inability to identify multi-locus virulence factors that are not clustered tightly and lack of studies applying it to other pathogens.

As noted earlier, traits related to virulence and antibiotic resistance are closely related. Hence, databases and tools related to AMR are relevant to VFARs. One such online resource is the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Online Analysis Pipeline which combines a manually vetted database of known AR genes with a pipeline using optimized cut-off parameters for fast detection, classification, and quantification of ARG genes at type, subtype, and reference levels using metagenomics data.36 The tool utilizes a structured ARG reference database that contains 4246 non-redundant sequences, curated with sequences integrated from other databases (e.g., CARD). It was developed using the Galaxy web server (an open, web-based platform for data intensive biomedical research37 available at http://galaxyproject.org/). The Galaxy web server allows the creation of an instance of services either on a public server or locally to perform and share targeted sequence analysis. After a pre-screening of metagenomes using UBlast,38 sequences can be uploaded to the Galaxy web server for analysis. The ARG pipeline is available at http://smile.hku.hk/SARGs.

ResFinder is another web-based tool for the identification of antimicrobial resistant genes from WGS data using BLAST.39 The tool could identify the presence of resistant genes in 1862 WGS from 12 different antimicrobial classes with 100% success. The method was further validated by a strong correlation between the computational predictions and phenotypic testing for 23 samples from 5 bacterial species. By expanding the reference data, this tool may detect antibiotic resistance due to single nucleotide polymorphisms. ResFinder can be accessed at http://www.genomicepidemiology.org.

The remaining tools included in this section (Xander and Vikodak) are not necessarily focused on virulence but are broadly useful to predict a given function. Xander assembles and retrieves user-selected genes of interest40 from metagenomics data. Therefore, it could be used to screen for multiple virulence genes, resistance determinants, and other genes of interest in parallel. A user-assembled reference set of sequences is required for each gene, which can be collected using tools such as the Functional Gene Pipeline Repository (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/).41 Among other applications, Xander has been used to examine the modulation of community and functional markers in a murine gut microbiome in response to an environmental contaminant.42

Vikodak is a multi-modular package with an ability to infer the functional potential of any microbial community based on its 16S rRNA gene diversity.43 The metabolic potential of any population is a direct function of total genes and proteins which are encoded and expressed by specific microbes in a community. By utilizing the readily available 16S rRNA gene sequence data and proteomic information about the specific microbes, this tool can infer the functional or metabolic potential of the community. In the validation study of this tool, Vikodak clustered the pathway abundance profiles belonging to 29 deep and 30 shallow periodontal samples against healthy controls, and differentiated virulent from non-virulent microbial communities. The functional profile data of 103 gut metagenomes indicated a high degree of correlation with the WGS derived functional predictions. Overall Vikodak's utility has been validated with more than 1400 metagenomic samples. The utility of Vikodak may depend upon the depth of sequencing used for the 16S rRNA gene or metagenomics. It is available at http://www.metagenomics.atc.tcs.com/vikodak.

Proteomics tools

Analytical and bioinformatics tools related to proteomics have also seen significant developments. Techniques such as tandem mass tags44 and isobaric tags are now available for relative and absolute quantification of proteins and proteomes.45 Although, these techniques are still expensive (e.g., $500 per sample) and not available broadly, they allow reduced analysis cost per sample and rapid analysis by multiplexing of samples (8 to 12 plex). The associated bioinformatics tools focusing on proteomics, some of which directly relevant to VFARs, are described below.

Predict Pathogenic Proteins in Metagenomic Datasets (or MP 3) is a standalone tool for the prediction of pathogenic proteins.46 MP 3 integrates two machine learning approaches – Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Hidden Markov Model (learning algorithms used to classify and predict outcomes) to carry out accurate, sensitive, and rapid protein predictions in genomic and meta-genomics datasets. In a blind dataset constructed using 200 complete protein sequences, MP 3 could achieve a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 92%, 100%, and 96% respectively. However, in a blind metagenomics dataset, the accuracy decreased to below 90%. A valuable feature of MP 3 is its ability to work with fragments of virulent proteins obtained from relatively short (100 to 150 bp) metagenomics reads. This feature allows comparison of pathogenic proteins in diseases and control samples without the use of laborious homology-based alignment. MP 3 and associated tools can be accessed at http://metagenomics.iiserb.ac.in/mp3/index.php.

VirulentPred is also a protein prediction tool utilizing two layers of SVMs.47 In this tool, the user is required to feed protein sequences in the FASTA format to predict the virulence. Using an SVM algorithm, first layer output based on an amino acid, dipeptide, higher order dipeptide composition and PSI-BLAST (Position-Specific Iterative Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) results are generated which are then used to train the second layer classifier. In a blind data set of 83 protein sequences, it could predict approximately 83% virulent and 81% non-virulent proteins. A five-fold cross-validation strategy was opted to evaluate the predictions. A major limitation of VirulentPred is its inability to correctly predict the virulence for eukaryotic proteins (56% accuracy). This difference may be due to the compositional differences between eukaryotic and prokaryotic virulent proteins. VirulentPred is available at http://www.bioinfo.icgeb.res.in/virulent/.

Another proteomic tool is VICMpred – specifically designed for Gram-negative bacterial proteins.48 It also relies on SVMs and uses tetrapeptides as an input for predicting the function of proteins. In a dataset of 670 sequences, VICMpred could achieve a prediction accuracy of ~68%. When amino acid information was also added along with tetrapeptide information, the accuracy increased to ~71%. Of the 670 proteins in the training dataset, approximately 10% were identified as virulence factors. Because VICMpred is designed for single-function proteins with a focus on Gram-negative bacteria, its utility for multifunctional proteins may be limited. It is available at http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/vicmpred/.

Some of the proteomics-based tools, although unique in their capabilities, do not provide web-based services. These include virulent-GO,49 integrated query networks,50 and protein–protein interaction networks.51 Virulent-GO is a Gene Ontology (GO) annotation-based tool for the prediction of virulent proteins in bacterial pathogens.49 GO annotation describes the functions of genes and their products across the species. Virulent-GO employs a two-stage approach for the classification of virulent proteins. In stage 1, the protein sequences in each dataset are used to obtain their homologies. The acquired accession numbers of homologies are then used as an input to the GO annotation database to obtain instructive GO terms. In stage 2, a high-performance classifier uses these instructive GO terms to classify the proteins. Multiple classifiers validated on an independent dataset are available. The accuracy of virulent-GO is around 83% using a single GO term. The performance of the model can further be enhanced by incorporating instructive GO terms with additional sequence based features like amino acid and dipeptide compositions.

Integrated query networks rely on information available in different biological repositories. An integrated query graph is used to link all available information related to specific proteins providing enhanced coverage of functional data for a given protein.50 Because this model relies on multiple data sources, its accuracy is dependent on the choice of data sources and cross-linkages. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks are based on Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interactive Genes/Proteins database for the identification of virulence factors in the proteomes of different bacteria.51 In PPI networks, two types of information are considered for the prediction of virulence factors: (i) the number of neighbouring nodes (to proteins), and (ii) confidence scores based on strengths of interactions with them. The identification accuracy of PPI networks is around 0.9–significantly higher than those obtained using sequence-based prediction methods. One apparent limitation of this approach is the false negative result due to the use of the limited negative dataset. With an increase in available PPI networks, this approach may play a significant role in developing new strategies for in-depth investigation of virulence.

Assessment of virulence in environmental samples

Multiple studies have focused on assessing virulence in environmental samples and clinical isolates.52–54 These include examining the abundance and frequency of virulence genes, antibiotic resistance determinants, and mobile genetic elements. Previous efforts using genomics to assess virulence in environmental samples focused on multiple genetic markers conferring virulence or antibiotic resistance. For example, one study used polymerase chain reactions with assays targeting 58 virulence genes in E. coli to assess the risk.55 The authors found no correlation between the number of genes detected and the number of viable E. coli bacteria. Similar studies have tested for the presence of virulence genes in Aeromonas isolated from drinking water treatment processes.56 Using quantitative polymerase chain reactions, the authors demonstrated variations in the distribution of three virulence genes – namely aer, ser, and alt, and concluded that the method was well suited for risk assessment in water. More recent studies in wastewater treatment plants have used shotgun metagenomics and other tools to analyze the abundance of virulence genes57 and co-presence of virulence and antibiotic resistance determinants and associated environmental factors.58 Similar studies are available for samples from water treatment plants59 and drinking water distribution systems.60

The goal of these studies was to characterize the presence of virulence genes. However, the mere presence of any one gene by itself does not necessarily indicate virulent activity or disease-causing potential.61 This may be due to several reasons including (i) the method for assessing the presence of virulence genes typically only detects gene fragments, not complete genes or linkages to other genes, (ii) fragments might be from nonviable organisms or extracellular DNA, (iii) activity may only be conveyed if other genes or mechanisms are present or absent, and (iv) the presence of resistance determinant is not necessarily hazardous, especially if they are part of the natural resistome. Failure to quantitatively link ARGs, mobile genetic elements, and virulence genes among each other and to risk of disease has so far prevented researchers to adequately employ for regulatory and control purposes. A resistance determinant linked to a virulence marker or a mobile genetic element is a greater threat due to its potential for horizontal transmission to other pathogens. Studies examining methods to establish such linkages with certainty have focused on obtaining long read sequencing, better means of sequence assembly, and source-tracking methods based on the WGS of isolates.

The MinION, for example, provides an average read length of 5000 bp and was used to examine the genomic regions that have all ARGs, mobile genetic elements, and virulence genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi H58.62 In another study, inverse polymerase chain reactions were used to enrich long fragments adjacent to ARGs in environmentally complex samples, which identified novel ARG sequences and genetic linkages to mobile genetic elements.63

Interest in establishing markers that differentiate host-specific pathogens from those present in the environment has long history due to its regulatory and microbial ecology implications. Due to the ease of WGS analysis, many examples exist where this has been demonstrated in their respective niches. For example, recent studies have identified genes that can potentially be used to differentiate E. coli strains from environmental and clinical sources (Table 2). The clustering of various E. coli clades observed by whole genome sequences64 confirmed the clustering observed via multi-locus sequence typing,65 and indicated that about 84 genes are unique to environmental E. coli and 120 genes are unique to pathogenic E. coli, some of which are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of potential E. coli genetic markers for differentiating sources and pathogenicity

| Microbial group | Marker genes |

|---|---|

| Total coliform | Lactose utilization: lacZ (several sets of alleles) |

| E. coli | Gluocoronidase: uidA, gadA, fimH |

| Pathogenic E. coli | Various virulence genes: stx1/2, eae, eltA, estA, Bfp, eaeA, aafA, aggR, hlyA, cdtA, senA, ipaH |

| Environmental E. coli | Genes related to lysozyme production and diol utilization: acmA (lysozyme M1 1,4-β-N-acetylmuramidase), eutL (ethanolamine utilization), pduL (propanediol utilization), yjhH (dihydrodipicolinate synthase), rfaQ (ADP-heptose), rfaI (lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis), pduE (propanediol dehydratase small subunit), relE (cytotoxic translational repressor of toxin-antitoxin stability systems) |

Another study exploring mobile ARGs, collected from the ResFinder database and mobile genetic elements in 23 425 sequenced bacterial genomes, could rank potential for transmission based on phylogeny.66 The majority of mobile ARGs were observed in Proteobacteria.67 This may be expected as many clinical pathogens are within this group, which are presumably under greater selective pressure due to antibiotic treatment. Similarly, analysis of genomic islands has been used to track the clinical vs. environmental origin of Burkholderia pseudomallei with genomic islands GI8.1, GI8.2 and GI16c indicative of clinical isolates.68 Molecular markers are also available for differentiating species of mycobacteria species involved in nosocomial infections and occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to metalworking fluid exposures.69 This is done using the internal transcribed spacer region between 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes.

In yet another example, the panton-valentine leukocidin gene, thought to be specific to the community associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, may help differentiate healthcare associated with community-acquired strains.70 The presence or absence of the coagulase gene – coa or the two-component system regulator gene-vicK, can be used to differentiate S. aureus from other staphylococci that are often present in humans.71 Markers can also be used for species-specific differentiation along with an assortment of antibiotic resistance gene markers that may confer resistance in staphylococci (e.g., the elongation factor Tu or tuf gene).

Thus, sequence information and mapping tools can be used to track the presence and emergence of genetic determinants in the environment and clinical settings with a reliable prediction of virulence.72 For selected niches, many assays targeting virulence and resistance determinants are available on simpler platforms.58,73,74 It is anticipated that future studies will focus on analyzing linkages among clusters of virulence genes, mobile genetic elements, and resistance genes to determine the health risk in environmental samples.75

Modulation of virulence by environment- and host-related factors

Genomics perhaps adequately describes the potential of virulence but fails to consider many environment- and host-related factors that may modulate the virulence. Some of these modulations are captured in transcriptomics and proteomics studies. However, many remain unaddressed. The leading approach for quantifying risk from microorganisms focuses on the fate, transport, growth, decay, and dilution among the many factors that affect the risk assessment. Long-term evolutionary changes in the pathogen due to factors related to the environment and the host resulting in novel resistances may also cause the risk to increase over time. Many of these characteristics are a function of the pathogen of interest and significant information exists to incorporate them into risk models.76–78

Environmental factors affecting the transport and survival of microorganisms include wind speed, sunshine, temperature, and precipitation, among other factors. High winds have been associated with dust particle attachment, survival, and transport of bacteria, viruses, and fungal spores.79–81 Factors such as hours of sunshine may have a negative effect on some pathogens such as Campylobacter due to UV rays,82 but may increase the proliferation for other pathogens such as Vibrio cholera.83 Similarly, humidity can directly influence the survival and transmission of diseases such as influenza84,85 or indirectly impact the numbers of disease-carrying vectors such as ticks and fleas.86 Aeroionisation and wind speed were responsible for suggesting the use of a set-back distance of 160 m during manure application to food crops.87 Risk can also be a function of the antimicrobial resistance or the potential to develop resistance over time following the use of a therapeutic molecule.88

Host-associated factors are also known to exacerbate or decrease the health risk of certain pathogens. Hosts that carry and transmit Clostridium difficile89 or methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus are well known.90 Host and commensal-based modulation of virulence is not well understood but it is recognized that commensals play a major role in outcompeting pathogens thus controlling their virulence.91 One study suggests that similar microbial populations form a barrier that can prevent over-colonization of virulent pathogens.92 Hosts with a mature immune system, such as those that are colonized by immune activators and suppressors (e.g., segmented filamentous bacteria and Bacteroides fragilis, respectively), are also less susceptible to pathogenic infection via the induction of regulatory host responses.93,94 The host response itself may be modulated by environmental factors. Although such modulations are only beginning to be understood in humans, studies in mice suggest that exposure to environmental toxicants influenced host susceptibility to infection95 and shifted gut commensal populations.96 Similarly, unsuitable environmental conditions (e.g., higher temperature) may suppress antibiotic production by bacterial commensals or increase the feeding rate thereby increasing its susceptibility to infection in plants.97,98 Thus, the growth, decay, and rate of emergence of resistance used to assess risk may all vary based on the pathogen identity, environmental factors, and host response.

Microbial risk models

Based on the potential for modulations described above, models have been developed to assess the risk of emergence and virulence, and even predict the outcome of biotherapies. Risk models based on environment–pathogen interactions, with emphasis on the potential for the emergence of transmission of a given pathogen under environmental conditions, are known. Using a newly developed statistical indicator termed relative sensitivity, a controlled study in China revealed that absolute humidity increased the transmission efficiency and survival of pathogens.99 Semenza described testing the European Environment and Epidemiology (E3) Network – a portal developed and maintained for the purpose of monitoring infectious disease epidemiology in Europe using known precursors.100 Described precursors included environmental conditions that allow for or stimulate the presence of diseases, and dispersal through air traffic. The results showed that the E3 network could be used to predict vector-borne disease threats.

Other models consider interactions between host–pathogen, pathogen–environment, and pathogen–commensals. For example, the “Host–Pathogen Interaction Database” – a database of protein–protein interactions,101 can be used to identify, search, or study proteins involved in host–pathogen interactions. At present, it contains data of 18 separate pathogens and 6 different hosts. Models combining RNA-seq, proteomics, and metadata to predict host–pathogen interactions have also been suggested.102 Such tools could be used to help predict the outcome of bacterio-therapies such as shown in one study examining the influence of probiotic strains on C. difficile infected gnotobiotic mice.103 The tool could predict bacterial communities that inhibit pathogen growth and strains that aid in resistance to community perturbations.

Disease prioritization, needed to help decision-makers focus on prevention and control of the greatest threats, must include many of the modulation factors described above. A multi-criteria decision analysis prioritization approach was described, with 40 questions encompassing known disease epidemiology, the influence of climate change, economic and social impact, the burden of diseases, and the ability to monitor and control.104 A review by O'Brien and co-authors examined five prioritization methodologies (Delphi, bibliometrics, qualitative algorithm, multi-criteria decision analysis, and questionnaire studies) described in 17 published studies for ranking communicable disease threats.105 The authors concluded that no method is superior, but observed that common practices in all methods could be employed in a superior manner.

While these models are indeed multifaceted, virulence assessment for waterborne pathogens may require predictive tools that encompass all known modulation factors on multiple scales including the individual, community, regional, and global scales.106 At the community level, factors to consider may include access to clean drinking water and resources for mitigation. Communities with a lower income may be at a greater risk to emergence and transmission. The individual level may require consideration of host susceptibility (e.g., levels of the select important commensals in the gut microbiome).

Limitations of VFARs

It is evident that factors associated with the pathogen, environment, treatment technology, and host are many and a deterministic model even when possible may have many uncertainties. Predictions about complex biological systems have always included some level of uncertainty.107 However, uncertain parameters do not necessarily lead to uncertain predictions, even for complex biological systems,108 provided that accurate models exist. This suggests that even though VFARs may be difficult to assess for the entire set of pathogenic microorganisms, it is possible to apply them to a limited set of microorganisms relevant to a given niche under controlled conditions such as those needed to formulate the CCL. The limitation that “The prediction of virulence based on the presence of virulence genes in E. coli may not always be accurate”,109 is perhaps true for most organisms. It may be more appropriate to combine results from different approaches and recognize that predictive models based on omics alone may miss or ignore potential virulence factors that are uncharacterized or not yet fully understood.110

There is also a lack of data on the “activity” component of VFARs compared to the “virulence factor” part. The fact that microbes have the potential to change in the environment, i.e., gain or lose genes111 (some of which may be less or more virulent) does not help.112 Mobile genetic elements are key in this fluidity of virulence and activity among organisms, as they are mediators of horizontal gene transfer and have been called “agents of open source evolution”.113 Characterizing these elements in addition to genes is becoming an increasingly commonplace, particularly in AR research, as they are important mechanisms in the dissemination of AR genes. The fact that loss or gain of “gene families” is at least 25-fold slower provides information to handle such factors in a quantitative manner, however.114,115 Control on genome engineering is also improving. For single genomes (and soon for communities), it is possible to implement the “Design-Build-Test-Learn” cycle which is a hallmark of engineering disciplines.116

Approaches to quantifying the pathogenic activity using in vivo models is perhaps the most significant limitation mainly due to the cost associated with such studies. Many groups are now utilizing alternate cost-effective in vivo models, e.g., small embryos of zebrafish117 and nematodes like Caenorhabditis elegans118 for virulence evaluation. Recently introduced organ-on-chip systems may also be employed for assessing the effect of virulence factors.119

Summary

Given the significant progress made in omics technologies, it is evident that the potential for semi-quantitative ranking of microbial hazards can now be realized by integrating the omics data (mostly quantitative) with virulence modulation data (still mostly qualitative). It is also obvious that there may be significant data gaps for a given scenario or application that must be filled. Fortunately, most omics data are easily and economically obtainable by high-throughput approaches available today. Data about modulation, especially by the host, are more difficult to obtain, but given that the most vulnerable population must be protected, decisions can be made conservatively. Combined with the occurrence, treatment response, and benefit-cost analysis data, it should now be possible to use the proposed VFAR approach in a manner that incorporates many, if not all, components of the originally proposed VFAR concept. If true, this will be the first example of integrating omics data with factors related to virulence modulation, and engineering analysis (occurrence, treatment, and benefit-cost analysis) in making decisions related to public and ecosystem health. Lessons from environmental impact assessment, risk, and statistical approaches can be learnt to ensure robustness and incorporate the level of uncertainty that is the hallmark of all biological systems.

Environmental impact.

Virulence factor activity relationships (VFARs) for microorganisms is a concept based on quantitative structure activity relationships (QSAR) for chemicals. It was proposed in a National Research Council report. The extensive data now available related to whole genome sequences of bacteria, and bioinformatics tools that could be used to analyze virulence factors are reviewed here for their usefulness to develop VFARs and help in developing a ranking system for waterborne pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program Grant No. P42 ES04911 with contributions from Projects 4, 5, and Core B.

References

- 1. [accessed December 2016];Classifying Drinking Water Contaminants for Regulatory Consideration. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10080.html. [PubMed]

- 2.Cherkasov A, Muratov EN, Fourches D, Varnek A, Baskin II, Cronin M, Dearden J, Gramatica P, Martin YC, Todeschini R, Consonni V, Kuz'min VE, Cramer R, Benigni R, Yang C, Rathman J, Terfloth L, Gasteiger J, Richard A, Tropsha A. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:4977–5010. doi: 10.1021/jm4004285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren X. Virulence. 2013;4:437–438. doi: 10.4161/viru.26211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Leon R. J. Water Health. 2009;7:94–100. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cangelosi GA. J. Water Health. 2009;7:64–74. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra AK, Graf J, Horneman AJ, Johnson JA. J. Water Health. 2009;7:29–54. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.José Figueras M, Borrego JJ. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010;7:4179–4202. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7124179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tourlousse DM, Stedtfeld RD, Baushke SW, Wick LM, Hashsham SA. Water Environ. Res. 2007;79:246–259. doi: 10.2175/106143007x156826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, Bult CJ, Kerlavage AR, Sutton G, Kelley JM, Fritchman RD, Weidman JF, Small KV, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback TR, Saudek DM, Phillips CA, Merrick JM, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Bott KF, Hu PC, Lucier TS, Peterson SN, Smith HO, Hutchison CA, Venter JC. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee S, Stamatis D, Bertsch J, Ovchinnikova G, Verezemska O, Isbandi M, Thomas AD, Ali R, Sharma K, Kyrpides NC, Reddy TBK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016:992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Power PM, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Moxon ER, Hood DW. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser CM, Eisen JA, Salzberg SL. Nature. 2000;406:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35021244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.I. Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. [Google Scholar]

- 14. [accessed December 2016];CNN Tech. http://www.money.cnn.com/2013/06/25/technology/enterprise/low-cost-genome-sequencing/

- 15. [accessed December 2016];Next Big Future. http://www.nextbigfuture.com/2016/06/chinas-92-billion-precision-medicine.html.

- 16.Di Ventra M, Taniguchi M. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016;11:117–126. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mochida K, Shinozaki K. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:2017–2038. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horgan RP, Kenny LC. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;13:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holliday GL, Bairoch A, Bagos PG, Chatonnet A, Craik DJ, Finn RD, Henrissat B, Landsman D, Manning G, Nagano N, O'Donovan C, Pruitt KD, Rawlings ND, Saier M, Sowdhamini R, Spedding M, Srinivasan N, Vriend G, Babbitt PC, Bateman A. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2015;83:1005–1013. doi: 10.1002/prot.24803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [accessed December 2016];Meatbolomics Society: Databases. http://www.metabolomicssociety.org/resources/metabolomics-databases.

- 21. [accessed December 2016];Lipidomics Gateway. http://www.lipidmaps.org/data/databases.html.

- 22.Cui W, Chen L, Huang T, Gao Q, Jiang M, Zhang N, Zheng L, Feng K, Cai Y, Wang H. Mol. BioSyst. 2013;9:1447–1452. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70024k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis JJ, Boisvert S, Brettin T, Kenyon RW, Mao C, Olson R, Overbeek R, Santerre J, Shukla M, Wattam AR, Will R, Xia F, Stevens R. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:276930. doi: 10.1038/srep27930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bashir M, Ahmed M, Weinmaier T, Ciobanu D, Ivanova N, Pieber TR, Vaishampayan PA. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [accessed Feburary 2017];US EPA (Microbial Contaminants CCL-4) http://www.epa.gov/ccl/microbial-contaminants-ccl-4.

- 26.Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Woyke T, Huntemann M, Anderson I, Billis K, Varghese N, Mavromatis K, Pati A, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D560–D567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wattam AR, Abraham D, Dalay O, Disz TL, Driscoll T, Gabbard JL, Gillespie JJ, Gough R, Hix D, Kenyon R, Machi D, Mao C, Nordberg EK, Olson R, Overbeek R, Pusch GD, Shukla M, Schulman J, Stevens RL, Sullivan DE, Vonstein V, Warren A, Will R, Wilson MJC, Yoo HS, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Sobral BW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D581–D591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. [accessed Feburary 2017];Victors virulence factors. http://www.phidias.us/victors/

- 29.Chen L, Zheng D, Liu B, Yang J, Jin Q. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D694–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McArthur AG, Waglechner N, Nizam F, Yan A, Azad MA, Baylay AJ, Bhullar K, Canova MJ, De Pascale G, Ejim L, Kalan L, King AM, Koteva K, Morar M, Mulvey MR, O'Brien JS, Pawlowski AC, Piddock LJV, Spanogiannopoulos P, Sutherland AD, Tang I, Taylor PL, Thaker M, Wang W, Yan M, Yu T, Wright GD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Vega Thurber RL, Knight R, Beiko RG, Huttenhower C. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon SH, Park YK, Kim JF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D624–D630. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joensen KG, Scheutz F, Lund O, Hasman H, Kaas RS, Nielsen EM, Aarestrup FM. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:1501–1510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shestov M, Ontañón S, Tozeren A. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:773. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1957-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterfield NR, Sanchez-Contreras M, Eleftherianos I, Dowling A, Yang G, Wilkinson P, Parkhill J, Thomson N, Reynolds SE, Bode HB, Dorus S, ffrench-Constant RH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:15967–15972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Jiang X, Chai B, Ma L, Li B, Zhang A, Cole JR, Tiedje JM, Zhang T. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2346–2351. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, Galaxy Team T. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Jiang X-T, Zhang T, Thomas T, Gilbert J, Meyer F, Sboner A, Mu X, Greenbaum D, Auerbach R, Gerstein M, Pennisi E, Hess M, Sczyrba A, Egan R, Kim T, Chokhawala H, Albertsen M, Hugenholtz P, Skarshewski A, Nielsen K, Tyson G, Scholz M, Lo C, Chain P, Altschul S, Madden T, Schäffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Kent W, Ye Y, Choi J, Tang H, Zhao Y, Tang H, Ye Y, Edgar R, Yu K, Zhang T, Liu B, Pop M, McArthur A, Waglechner N, Nizam F, Yan A, Azad M, Yang Y, Li B, Ju F, Zhang T, MacDonald N, Parks D, Beiko R, Cai L, Yu K, Yang Y, Chen B-W, Li X-D, Yang Y, Yu K, Xia Y, Lau F, Tang D, Chao Y, Ma L, Yang Y, Ju F, Zhang X. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Fish JA, Gilman M, Sun Y, Brown CT, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Microbiome. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fish JA, Chai B, Wang Q, Sun Y, Brown CT, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:291. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stedtfeld RD, Stedtfeld TM, Fader KA, Williams MR, Quensen J, Zacharewski TR, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix058. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagpal S, Haque MM, Mande SS. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dayon L, Sanchez J-C. Methods in molecular biology. Vol. 893. Clifton, N.J.: 2012. pp. 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumura CY, Menezes de Oliveira B, Durbeej M, Marques MJ. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta A, Kapil R, Dhakan DB, Sharma VK. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg A, Gupta D. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saha S, Raghava GPS. Genomics, Proteomics Bioinf. 2006;4:42–47. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(06)60015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai C-T, Huang W-L, Ho S-J, Shu L-S, Ho S-Y. Proc. World. Acad. Sci. Eng. Tech. 2009;3:80. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cadag E, Tarczy-Hornoch P, Myler PJ. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13:321. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng L-L, Li Y-X, Ding J, Guo X-K, Feng K-Y, Wang Y-J, Hu L-L, Cai Y-D, Hao P, Chou K-C. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Menezes FGR, Neves S da S, de Sousa OV, Vila-Nova CMVM, Maggioni R, Theophilo GND, Hofer E, Vieira RHS dos F. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 2014;56:427–432. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000500010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sujatha S, Chandra P, Ira P. Indian. J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2013;56:24. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.116144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimani RW, Muigai AWT, Sang W, Kiiru JN, Kariuki S, Kimani R. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2014;3:1–7. doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v3i1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masters N, Wiegand A, Ahmed W, Katouli M. Water Res. 2011;45:6321–6333. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu CP, Chu KH. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011;176:225–238. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cai L, Zhang T. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:5433–5441. doi: 10.1021/es400275r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang B, Xia Y, Wen X, Wang X, Yang Y, Zhou J, Zhang Y. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang K, Zhang XX, Shi P, Wu B, Ren H. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014;109:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi P, Jia S, Zhang XX, Zhang T, Cheng S, Li A. Water Res. 2013;47:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rogers S, Commons R, Danchin MH, Selvaraj G, Kelpie L, Curtis N, Robins-Browne R, Carapetis JR. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195:1625–1633. doi: 10.1086/513875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ashton PM, Nair S, Dallman T, Rubino S, Rabsch W, Mwaigwisya S, Wain J, O'Grady J. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;33:296–300. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pärnänen K, Karkman A, Tamminen M, Lyra C, Hultman J, Paulin L, Virta M, D'Costa VM, Martinez JL, Bhullar K, Forsberg KJ, Segawa T, Perry JA, Wright GD, Muniesa M, Colomer-Lluch M, Jofre J, Li A, Li L, Zhang T, Davison J, Gaze WH, Martinez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F, Chambers L, Fitzpatrick D, Walsh F, Bengtsson-Palme J, Boulund F, Fick J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ, Ravi A, Koren S, Phillippy AM, Ni J, Yan Q, Yu Y, Ferrarini M, Mikheyev AS, Tin MMY, Ochman H, Gerber AS, Hartl DL, Muziasari WI, Tamminen M, Brown H, Stokes H, Hall R, McArthur AG, Bankevich A, Li D, Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin FYL, Bercot B, Poirel L, Silva-Sanchez J, Nordmann P, Ye J, Morgulis A, Edgar RC, Martin M, Bacci G, Bazzicalupo M, Benedetti A, Mengoni A, Li H, Durbin R, Bengtsson-Palme J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W, Fichot EB, Norman RS, Hyatt D, Koskinen P, Toronen P, Nokso-Koivisto J, Holm L, Pei R, Kim S, Carlson KH, Pruden A. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35790. doi: 10.1038/srep35790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo C, Walk ST, Gordon DM, Feldgarden M, Tiedje JM, Konstantinidis KT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:7200–7205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015622108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walk ST, Alm EW, Gordon DM, Ram JL, Toranzos GA, Tiedje JM, Whittam TS. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6534–6544. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01262-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Y, Yang X, Li J, Lv N, Liu F, Wu J, Lin IYC, Wu N, Weimer BC, Gao GF, Liu Y, Zhu B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:6672–6681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01802-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bartpho T, Wongsurawat T, Wongratanacheewin S, Talaat AM, Karoonuthaisiri N, Sermswan RW, Currie B, Palasatien S, Lertsirivorakul R, Royros P, Wongratanacheewin S, Sermswan R, Woods D, Chaowagul W, White N, Dance D, Wattanagoon Y, Naigowit P, White N, Cheng A, Currie B, Vesaratchavest M, Tumapa S, Day N, Wuthiekanun V, Chierakul W, Sermswan R, Wongratanacheewin S, Trakulsomboon S, Thamlikitkul V, Ulett G, Currie B, Clair T, Mayo M, Ketheesan N, Sim S, Yu Y, Lin C, Karuturi R, Wuthiekanun V, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, Holden M, Titball R, Peacock S, Cerdeno-Tarraga A, Atkins T, Tuanyok A, Leadem B, Auerbach R, Beckstrom-Sternberg S, Beckstrom-Sternberg J, Hacker J, Carniel E, Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J, Ahmed N, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, Hasnain S, Dobrindt U, Agerer F, Michaelis K, Janka A, Buchrieser C, Tumapa S, Holden M, Vesaratchavest M, Wuthiekanun V, Limmathurotsakul D, Rajashekara G, Glasner J, Glover D, Splitter G, Weaver D, Karoonuthaisiri N, Tsai H, Huang C, Ho M, Jayapal K, Lian W, Glod F, Sherman D, Hu W, Wu C, Glasner J, Collins M, Naser S, Talaat A, Moore R, Reckseidler-Zenteno S, Kim H, Nierman W, Yu Y, Ong C, Ooi C, Wang D, Chong H, Ng K, Kim H, Schell M, Yu Y, Ulrich R, Sarria S, Sarmiento-Rubiano L, Berger B, Moine D, Zuniga M, Perez-Martinez G, Juhas M, van der Meer J, Gaillard M, Harding R, Hood D, Tiyawisutsri R, Holden M, Tumapa S, Rengpipat S, Clarke S, Subsin B, Thomas M, Katzenmeier G, Shaw J, Tungpradabkul S, Shalom G, Shaw J, Thomas M, Loprasert S, Sallabhan R, Whangsuk W, Mongkolsuk S, Singh R, Wiseman B, Deemagarn T, Donald L, Duckworth H, Korbsrisate S, Tomaras A, Damnin S, Ckumdee J, Srinon V, Vellasamy K, Vasu C, Puthucheary S, Vadivelu J, Vanaporn M, Vattanaviboon P, Thongboonkerd V, Korbsrisate S, Song Y, Xie C, Ong Y, Gan Y, Chua K, Loprasert S, Sallabhan R, Whangsuk W, Mongkolsuk S, Sarkar-Tyson M, Thwaite J, Harding S, Smither S, Oyston P, Woo P, Woo G, Lau S, Wong S, Yuen K, Samosornsuk N, Lulitanond A, Saenla N, Anuntagool N, Wongratanacheewin S, Quackenbush J, Yang Y, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin D, Peng V, Bengtsson H, Jonsson G, Vallon-Christersson J, Bengtsson H, Hossjer O, Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash A, Madigan M, Martinko J, Parker J. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khan IUH, Selvaraju SB, Yadav JS. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4466–4472. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4466-4472.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsiao C-H, Ong SJ, Chuang C-C, Ma DHK, Huang Y-C. J. Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/923941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rallapalli S, Verghese S, Verma RS. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;26:361–364. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.43580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stedtfeld RD, Williams MR, Fakher U, Johnson TA, Stedtfeld TM, Wang F, Khalife WT, Hughes M, Etchebarne BE, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016;92:020. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stedtfeld RD, Baushke SW, Tourlousse DM, Miller SM, Stedtfeld TM, Gulari E, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:3831–3838. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02743-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kostić T, Ellis M, Williams MR, Stedtfeld TM, Kaneene JB, Stedtfeld RD, Hashsham SA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:7711–7722. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson TA, Stedtfeld RD, Wang Q, Cole JR, Hashsham SA, Looft T, Zhu Y-G, Tiedje JM. mBio. 2016;7:e02214–e02215. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02214-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perkins TL, Perrow K, Rajko-Nenow P, Jago CF, Jones DL, Malham SK, McDonald JE. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;572:1645–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Altizer S, Ostfeld RS, Johnson PTJ, Kutz S, Harvell CD. Science. 2013;341:514–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1239401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu X, Lu Y, Zhou S, Chen L, Xu B. Environ. Int. 2016;86:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Griffin DW. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:459–477. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schlesinger P, Mamane Y, Grishkan I. Aerobiologia. 2006;22:259–273. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen P-S, Tsai FT, Lin CK, Yang C-Y, Chan C-C, Young C-Y, Lee C-H. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:1211–1216. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Obiri-Danso K, Paul N, Jones K. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;90:256–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Islam MS, Sharker MAY, Rheman S, Hossain S, Mahmud ZH, Islam MS, Uddin AMK, Yunus M, Osman MS, Ernst R, Rector I, Larson CP, Luby SP, Endtz HP, Cravioto A. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;103:1165–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shaman J, Kohn M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu B, Jin Z, Jiang Z, Guo J, Timberlake M, Ma X. Global Urban Monitoring and Assessment through Earth Observation. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2014. Climatological and Geographical Impacts on the Global Pandemic of Influenza A (H1N1) 2009; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gage KL, Ostfeld RS, Olson JG. J. Mammal. 1995;76:695–715. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jahne MA, Rogers SW, Holsen TM, Grimberg SJ, Ramler IP, Kim S. J. Environ. Qual. 2016;45:666. doi: 10.2134/jeq2015.04.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fullybright R, Dwivedi A, Mallawaarachchi I, Sinsin B. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;35:1259–1267. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2659-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Zabarsky TF, Eckstein EC, Jump RLP, Donskey CJ. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:992–998. doi: 10.1086/521854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Monecke S, Ehricht R, Slickers P, Wiese N, Jonas D. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009;28:1383–1390. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rea MC, O'Sullivan O, Shanahan F, O'Toole PW, Stanton C, Ross RP, Hill C. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:867–875. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05176-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ducluzeau R, Raibaud P. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 1989;8:313–332. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Cell. 2005;122:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, Imaoka A, Itoh K, Takeda K, Umesaki Y, Honda K, Littman DR. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thigpen JE, Faith RE, McConnell EE, Moore JA. Infect. Immun. 1975;12:1319–1324. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.6.1319-1324.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang Y-J, Li S, Gan R-Y, Zhou T, Xu D-P, Li H-B. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:7493–7519. doi: 10.3390/ijms16047493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Humair B, González N, Mossialos D, Reimmann C, Haas D. ISME J. 2009;3:955–965. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elderd BD, Reilly JR. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014;83:838–849. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang Y, Rao Y, Wu X, Zhao H, Chen J. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:767–783. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120100767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Semenza JC. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:6333–6351. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kumar R, Nanduri B, Guldener U, Munsterkotter M, Oesterheld M, Pagel P, Ruepp A, Mewes H, Stumpflen V, Prasad TK, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, Salwinski L, Miller C, Smith A, Pettit F, Bowie J, Eisenberg D, Aranda B, Achuthan P, Alam-Faruque Y, Armean I, Bridge A, Derow C, Feuermann M, Ghanbarian A, Kerrien S, Khadake J, Gilbert D, Matthews L, Gopinath G, Gillespie M, Caudy M, Croft D, de Bono B, Garapati P, Hemish J, Hermjakob H, Jassal B, Zanzoni A, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Quondam M, Ausiello G, Helmer-Citterich M, Cesareni G, Driscoll T, Dyer M, Murali T, Sobral B, Winnenburg R, Urban M, Beacham A, Baldwin T, Holland S, Lindeberg M, Hansen H, Rawlings C, Hammond-Kosack K, Kohler J, Navratil V, de Chassey B, Meyniel L, Delmotte S, Gautier C, Andre P, Lotteau V, Rabourdin-Combe C, Zhang C, Crasta O, Cammer S, Will R, Kenyon R, Sullivan D, Yu Q, Sun W, Jha R, Liu D, Dyer M, Murali T, Sobral B, Kim J, Park D, Kim B, Cho S, Kim Y, Park Y, Cho H, Park H, Kim K, Yoon K, Lee S, Chan C, Tsai C, Lai J, Wang F, Kao C, Huang C, Chen C, Lin C, Lo Y, Yang J, Altschul S, Madden T, Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D, Killcoyne S, Carter G, Smith J, Boyle J, Chen L, Yang J, Yu J, Yao Z, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin Q. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:S16. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dix A, Vlaic S, Guthke R, Linde J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bucci V, Tzen B, Li N, Simmons M, Tanoue T, Bogart E, Deng L, Yeliseyev V, Delaney ML, Liu Q, Olle B, Stein RR, Honda K, Bry L, Gerber GK, Bucci V, Xavier J, Gerber G, Donia M, Fischbach M, Rakoff-Nahoum S, Coyne M, Comstock L, Friedman J, Alm E, Marino S, Baxter N, Huffnagle G, Petrosino J, Schloss P, Butcher J, Fisher C, Mehta P, Love M, Huber W, Anders S, McMurdie P, Holmes S, Park T, Casella G, O'Hara R, Sillanpaa M, Mosimann J, Gerber G, Onderdonk A, Bry L, Schubert A, Sinani H, Schloss P, Schaubeck M, Haller D, Hou J, Lee D, Lewis J, Maurice C, Haiser H, Turnbaugh P, Macdonald B, Higham C, Husmeier D, Welch JM, Rossetti B, Rieken C, Dewhirst F, Borisy G, Bar-Joseph Z, Gerber G, Simon I, Gifford D, Jaakkola T, Leng C, Tran M, Nott D, Kass R, Raftery A, Aries V, Crowther J, Drasar B, Hill M, Bentley R, Meganathan R, Brandt L, Dabek M, McCrae S, Stevens V, Duncan S, Louis P, Derrien M, Vaughan E, Plugge C, Vos W, Gilliland S, Speck M, Hayakawa S, Hattori T, MacDonald I, Rochon Y, Hutchison D, Holdeman L, Macdonald I, White B, Hylemon P, Miller T, Wolin M, Pereira D, McCartney A, Gibson G, Salyers A, West S, Vercellotti J, Wilkins T, Suvarna K, Stevenson D, Meganathan R, Hudspeth M, Taranto M, Vera J, Hugenholtz J, Valdez G, Sesma F, Kozich J, Westcott S, Baxter N, Highlander S, Schloss P, Wheeler T, Eddy S. Genome Biol. 2016;17:121. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cox R, Sanchez J, Revie CW, Greer A, Ng V, Fisman D, Furgal C, Seguin J, Oreskes N, Morse S, Krause G, Cox R, Revie C, Sanchez J, Linkov I, Satterstrom F, Kiker G, Batchelor C, Bridges T, Huang I, Keisler J, Linkov I, Bots P, Hulshof J, Soon J, Davies W, Chadd S, Baines R, Costa CBe, Chagas M, Vilas VDR, Voller F, Montibeller G, Franco L, Sribhashyam S, Gale P, Brouwer A, Ramnial V, Kelly L, Kosmider R, Peel M, Finlayson B, McMahon T, Ogden N, Lindsay L, Hanincova K, Barker I, Bigras-Poulin M, Hubalek Z, Doherty J, Murray C, Krause G, Morgan D, Kirkbride H, Hewitt K, Said B, Walsh A, Van der Fels-Klerx H, Cooke R, Nauta M, Goossens L, Havelaar A, McKendrick I, Gettinby G, Gu Y, Reid S, Revie C, Steele K, Carmel Y, Cross J, Wilcox C, Guis H, Caminade C, Calvete C, Morse A, Tran A, Soverow J, Wellenius G, Fisman D, Mittleman M, Lambert RC, Kolivras K, Resler L, Brewster C, Paulson S, Tanowitz H, Weiss L, Montgomery S, Hasan N, Choi S, Eppinger M, Clark P, Chen A, Rose J, Epstein P, Lipp E, Sherman B, Bernard S, Patz J, Olson S, Uejio C, Gibbs H, Olson M, Budescu D, Gilsdorf A, Krause G, Aspinall W, Albert I, Donnet S, Guihenneuc-Joyaux C, Low-Choy S, Mengersen K, McKenzie J, Simpson H, Langstaff I, Horby P, Rushdy A, Graham C, O'Mahony M, Humblet M, Vandeputte S, Albert A, Gosset C, Kirschvink N, Pheloung P, Williams P, Halloy S, Anand P. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O’Brien EC, Taft R, Geary K, Ciotti M, Suk JE. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21:30212. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.17.30212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mellor JE, Levy K, Zimmerman J, Elliott M, Bartram J, Carlton E, Clasen T, Dillingham R, Eisenberg J, Guerrant R, Lantagne D, Mihelcic J, Nelson K. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;548–549:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zallot R, Harrison K, Kolaczkowski B, de Crécy-Lagard V. Life. 2016;6:39. doi: 10.3390/life6030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van Mourik S, ter Braak C, Stigter H, Molenaar J. PeerJ. 2014;2:e433. doi: 10.7717/peerj.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]