Abstract

Objective

Assess whether a commitment contract informed by behavioral economics leads to persistent virologic suppression among HIV-positive patients with poor antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence.

Design

Single-center pilot randomized clinical trial, plus a non-randomized control group.

Setting

Publicly-funded HIV clinic in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Intervention

The study involved three arms. (i) Participants in the provider visit incentive arm received $30 after attending each scheduled provider visit. (ii) Participants in the incentive choice arm were given a choice between the above arrangement and a commitment contract that made the $30 payment conditional on both attending the provider visit and meeting an ART adherence threshold. (iii) The passive control arm received routine care and no incentives.

Participants

110 HIV-infected adults with a recent plasma HIV-1 viral load (pVL) >200 copies/mL despite ART. The sample sizes of the three groups were as follows: provider visit incentive, n=21; incentive choice, n=19; passive control, n=70.

Main outcome measure

Virologic suppression (pVL≤200 copies/mL) at the end of the incentive period and at an unanticipated post-incentive study visit approximately three months later.

Results

The odds of suppression were higher in the incentive choice arm than in the passive control arm at the post-incentive visit (adjusted odds ratio 3.93, 95%CI 1.19 to 13.04, p=0.025). The differences relative to the passive control arm at the end of the incentive period and relative to the provider visit incentive arm at both points in time were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Commitment contracts can improve ART adherence and virologic suppression.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01455740

Keywords: Behavioral Economics, Commitment Contract, Financial Incentives, Antiretroviral Therapy, Adherence, HIV-1 Virologic Suppression

INTRODUCTION

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence is critical for HIV treatment to be successful but remains difficult for many individuals to maintain.1,2 Barriers to adherence include socioeconomic status, mental health, and substance abuse.3–6 Interventions that can improve adherence and demonstrate sustained virologic suppression for people living with HIV (PLWH) are needed. Conditional cash transfers (CCT)—monetary rewards tied to adherence—have produced mixed results in improving ART adherence.7–15 Even when financial incentives have shown positive impacts on adherence and viral suppression, the effect does not persist once incentives are withdrawn.15

This study leverages behavioral economics to improve the design of financial incentives for ART adherence.16–19 Individuals often intend to engage in healthy behaviors in the future, but when the moment to engage in such a behavior arrives, they frequently fail to follow through on their intentions, instead making choices that are expedient at the time. Commitment contracts allow individuals to tie their own hands—by choosing to make future incentive payments contingent on following through on good intentions, individuals can increase their own engagement in healthy behaviors.20,21 Commitment contracts have proved effective in promoting healthy behaviors, but to our knowledge they have never been used in HIV care.22–26

We hypothesized that participants offered a commitment contract for ART adherence would be more likely to be virologically suppressed at the end of the period during which the incentives were in effect, as well as at an unanticipated study visit after incentives had ended. To test our hypothesis, we used a randomized trial design combined with a comparison to a non-randomized control group, studying patients on appropriate ART having virologic failure within a publicly-funded HIV clinic serving Atlanta, Georgia.

METHODS

Design

The study used a randomized trial design for two treatment arms: (i) Participants in the provider visit incentive (PVI) arm were told that they would receive $30 after attending each scheduled provider visit (a CCT). (ii) Participants in the incentive choice (IC) arm were given a choice between the above CCT and a commitment contract, which made the $30 payment conditional on the patient attending the provider visit and meeting an ART adherence threshold. A block randomization scheme, stratified on whether or not the majority of the participant’s three previous viral load measurements were suppressed, assigned 21 individuals to the PVI arm and 19 to the IC arm.

The study also included 70 individuals in a passive control (PC) arm, who did not receive financial incentives. Individuals in the PC arm were not enrolled in the randomized trial but met basic study eligibility criteria during the same time period.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants in the PVI and IC arms were PLWH who attended the Grady Health System Infectious Disease Program (IDP). They were enrolled during November 2011 – April 2012 and were followed for a median of 15 months. To be eligible, an individual’s most recent HIV-1 plasma RNA viral load (pVL) must have been > 200 copies/mL and must have been measured within the prior 18 months and at least 6 months after starting the current ART regimen. The pool was further restricted to English-speaking adults who filled prescriptions through IDP, were not using pillboxes, were not planning to relocate, and were not enrolled in another trial.

To create a matched PC arm based on observational data, we identified individuals via IDP electronic health records (EHR). Because recruitment for the PVI and IC arms involved asking clinical staff to refer individuals who had difficulty with adherence, we restricted our search to adults who registered pVL > 200 copies/mL at some point in 2011 after having been on ART for at least six months. To parallel the enrollment process of the PVI and IC arms, we then narrowed the sample to individuals who visited IDP during 2012 and whose most recent pVL was > 200 copies/mL and measured within the prior six months. We further narrowed the sample to individuals who filled prescriptions through IDP and were not in the PVI or IC arms. The 2012 visit was considered the “enrollment visit,” and we tracked individuals forward in time from that point.

Description of the Intervention

All participants received the standard of care (SOC) at IDP, which included not only medical care but also a wide range of social services. In addition, participants in the PVI and IC arms received financial incentives designed to motivate health-improving behaviors. After the initial study enrollment visit, participants in the PVI arm received a $30 payment each time they showed up as scheduled for one of their next four HIV primary care visits. At the initial study enrollment visit, participants in the IC arm chose between either the incentive scheme assigned to the PVI arm (Attend Clinic Get Paid, ACGP) or an incentive scheme that tied payments to clinic attendance and ART medication adherence (Take Medications and Attend Clinic Get Paid, TMACGP). More precisely, participants who selected TMACGP received a $30 payment at each of their next four HIV primary care visits if they (i) showed up as scheduled and (ii) presented a dose-recording pill bottle cap indicating that they correctly took at least 90% of doses of a sentinel medication since the previous study visit (see the Supplementary Materials for the algorithm for assigning a sentinel medication).

Participants in the PVI and IC arms were also asked to return for a sixth, unanticipated study visit approximately three months after the last of the four study visits to which the incentive scheme applied. To reduce attrition, participants were offered $100 for showing up to the fifth and sixth study visits.

Data Collection

In both the PVI and IC arms, questionnaires were administered at each study visit, and adherence was measured using a dose-recording cap (Aardex Group, Switzerland).

EHR data were collected for all three arms, with “study visits” for the PC arm selected to match the study visit schedule for the other arms as closely as possible. HIV-1 pVL was assessed using Abbott Real Time HIV-1 assay (Abbott RT, Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany). The primary outcome of interest was virologic suppression (pVL ≤ 200 copies/mL, in accordance with Department of Health and Human Services guidelines at the time of the study) at the fifth study visit. A second outcome of interest was virologic suppression at the sixth visit. Missing values for pVL were coded as failures, but in supplementary analyses we find similar results using inverse probability weighting to correct for missing values.

Statistical Power

The study had 51% statistical power to detect an absolute difference of 30 percentage points between the PVI and IC groups’ rates of virologic suppression at a 5% significance level for a two-sided test. Comparing the IC and PC arms, the study had 67% power to detect the same difference.

Statistical Analysis

We used logistic regression to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted impact of the IC treatment relative to the PVI arm and relative to the PC arm. The predictor variables included treatment arm indicators and the stratifying variable. Our hypothesis tests were constructed relying on the asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimator, but we obtained similar results when we conducted permutation tests. All statistical procedures were implemented using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics and Data Summary

Supplementary analyses indicate that the three arms had similar demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline, although individuals in the PC arm were older (median age 48.93 years) than individuals in the IC arm (median 40.10) and PVI arm (median 42.88). Individuals in the IC arm had higher pVL values leading up to the enrollment visit relative to individuals in the other arms. The PC arm had a higher rate of missing pVL measurements at the fifth study visit compared to the other arms.

In the IC arm, 48% of participants had at least one suppressed viral load measurement across the three visits prior to the enrollment visit. The percentage was 43% in the PVI arm and 36% in the PC arm. Thus, many individuals in the study had experienced some previous success in achieving viral suppression, although some individuals in the study had faced much more difficulty achieving success in the past.

Plasma HIV-1 Viral Load Suppression

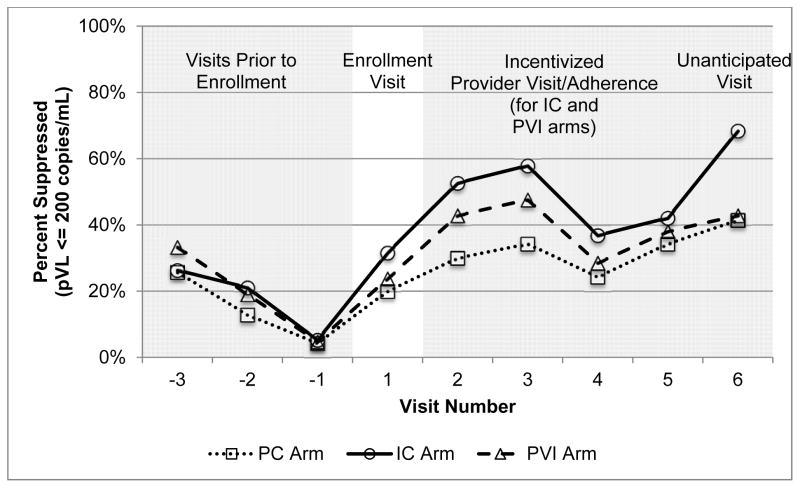

Figure 1 shows that for the three visits prior to enrollment, the percentage of individuals with suppressed viral load measurements was similar across arms. At the fifth study visit, the percentages suppressed were: IC arm 42%, PVI arm 38%, and PC arm 34%. At the sixth study visit, the percentages were: IC arm 68%, PVI arm 43%, and PC arm 41%.

Figure 1.

Percent Virologically Suppressed by Study Arm and Visit Number

Table 1 shows logistic regression results. The adjusted odds ratio of suppression in the IC arm relative to the PVI arm at the fifth visit was 1.57 (95%CI 0.25 to 9.92; p-value 0.630), and in the IC arm relative to the PC arm it was 1.44 (95%CI 0.46 to 4.49; p-value 0.52). At the sixth visit, the adjusted odds ratio of virologic suppression in the IC arm relative to the PVI arm was 3.38 (95%CI 0.77 to 14.84; p-value 0.107), and in the IC arm relative to the PC arm it was 3.93 (95%CI 1.19 to 13.04; p-value 0.025).

Table 1.

Virologic Suppression in the IC Arm Compared to the PVI Arm and the PC Arm

| Panel A: Virologic Suppression in the IC Arm Compared to the PVI Arm | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Unadj. Odds Ratio [95% conf. int.] | Adj. Odds Ratio [95% conf. int.] | |

|

|

||

| Virologic suppression at fifth visit | 1.16 [0.31,4.36] | 1.57 [0.25,9.92] |

| Virologic suppression at sixth visit | 3.17 [0.80,12.59] | 3.38 [0.77,14.84] |

|

| ||

| Panel B: Virologic Suppression in the IC Arm Compared to the PC Arm | ||

|

| ||

| Unadj. Odds Ratio [95% conf. int.] | Adj. Odds Ratio [95% conf. int.] | |

|

|

||

| Virologic suppression at fifth visit | 1.28 [0.44,3.77] | 1.44 [0.46,4.49] |

| Virologic suppression at sixth visit | 2.88* [0.98,8.47] | 3.93** [1.19,13.04] |

p<0.10

p<0.05

This table reports the results of logistic regressions where the outcome variable is an indicator for virologic suppression (pVL ≤200 copies/mL) at the fifth visit (the last incentivized visit for the IC and PVI arms) or at the sixth visit (the unanticipated post-incentive visit for the IC and PVI arms). Individuals who are missing a pVL measurement are coded as not suppressed.

The sample in Panel A is only participants in the IC and PVI arms, and this panel reports the odds ratio for the IC arm compared to the PVI arm. The unadjusted odds ratio is from a regression specification in which the predictor variables are the stratifying variable (an indicator for whether or not the majority of the previous three pVL measurements were suppressed) and an indicator for the IC arm. The adjusted odds ratio is from a regression specification that adds age, gender, race, baseline pVL, and mean pVL in the 6 months prior to the study as predictor variables.

The sample in Panel B includes participants in all three arms, and this panel reports the odds ratio for the IC arm compared to the PC arm. The unadjusted odds ratio is from a regression specification in which the predictor variables are the stratifying variable (an indicator for whether or not the majority of the previous three pVL measurements were suppressed), an indicator for the PVI arm, and an indicator for the IC arm. The adjusted odds ratio is from a regression specification that adds age, gender, race, baseline pVL, and mean pVL in the 6 months prior to the study as predictor variables.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using commitment contracts in HIV care. Many previous interventions have produced statistically significant effects on ART adherence that do not persist after the intervention ends. A notable feature of our study is that after the incentives for ART adherence and provider visits were removed, participants who had been offered a commitment contract for ART adherence were more likely to achieve virologic suppression relative to individuals who had been assigned a conditional cash transfer for provider visits and relative to individuals who had been assigned the standard of care, although the difference was only statistically significant in the latter comparison. There were differences in the prevalence of missing outcomes across groups, but these differences were not statistically significant for the unanticipated post-incentive visit and therefore were unlikely to be the explanation for the results. Thus, financial rewards coupled with individual choice can increase engagement in healthy behaviors after incentives are removed.

In the face of mixed evidence regarding the efficacy of conditional cash transfers for promoting ART adherence,7–15 our results offer a new perspective on the use of financial incentives. When individuals can choose whether or not to make financial rewards dependent on adherence, they may become more adherent both because of the direct incentive effect and because the ability to choose may increase feelings of personal engagement and empowerment in disease management.27

Replication is needed to address the limitations of our study, including its small sample size, as well as to determine whether similar findings are obtained in other settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Financial support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (P30AG034532), the Emory University Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409), and the Pershing Square Fund for the Foundations of Human Behavior.

We thank the patients and staff at the Grady Health System Infectious Disease Program for their generous contributions to this work, especially Christopher Foster, Elyse LaFond, and Tanisha Sullivan. We also thank Andrew Chong, Jonathan Cohen, Layne Kirshon, John Klopfer, Gwendolyn Reynolds, and Alexandra Steiny for their contributions.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2016. Abst. #1039

Supplementary Materials. Algorithm for Choosing Sentinel Medication

- If the individual has an agent from the protease inhibitor (PI) group, use it as the sentinel

- If no PI, use a non-nucleoside/tide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) as the sentinel

- If no PI or NNRTI, use raltegravir as the sentinel

- If no PI or NNRTI or raltegravir, use maraviroc as the sentinel

- If no PI or NNRTI or raltegravir or maraviroc, use a nucleoside/tide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) as the sentinel

Transparency Statement: The guarantors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies are disclosed.

Data Sharing Statement: The data are potentially sensitive and will not be shared.

Author Contributions: Marcella Alsan, John Beshears, Wendy S. Armstrong, and Vincent C. Marconi had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Design and conduct of the study: Marcella Alsan, John Beshears, Wendy S. Armstrong, James J. Choi, Brigitte C. Madrian, Carlos del Rio, David Laibson, and Vincent C. Marconi.

Collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data: Marcella Alsan, John Beshears, Wendy S. Armstrong, Minh Ly T. Nguyen, and Vincent C. Marconi.

Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: Marcella Alsan, John Beshears, Wendy S. Armstrong, James J. Choi, Brigitte C. Madrian, Minh Ly T. Nguyen, Carlos del Rio, David Laibson, and Vincent C. Marconi.

Ethics Approval: All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Emory University, Harvard University, and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Role of Study’s Sponsors: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the article.

Competing Interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the Corresponding Author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work other than from the National Institutes of Health (P30AG034532), the Emory University Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409), and the Pershing Square Fund for the Foundations of Human Behavior; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work, with the exception of the following: David Laibson is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the pharmacy benefit management company Express Scripts, a position for which he does not receive compensation.

References

- 1.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–1183. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ickovics J, Meade C. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among patients with HIV: A critical link between behavioral and biomedical sciences. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):98–102. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC, Grebler T. Stress and poverty predictors of treatment adherence among people with low-literacy living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):810–816. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f01be3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett PG, Sorensen JL, Wong W, Haug NA, Hall SM. Effect of incentives for medication adherence on health care use and costs in methadone patients with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1–2):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Operario D, Kuo C, Sosa-Rubí SG, Gálarraga O. Conditional economic incentives for reducing HIV risk behaviors: Integration of psychology and behavioral economics. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2283–2292. doi: 10.1037/a0032760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haug NA, Sorensen JL. Contingency management interventions for HIV-related behaviors. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(4):154–159. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigsby MO, Rosen MI, Beauvais JE, et al. Cue-dose training with monetary reinforcement: Pilot study of an antiretroviral adherence intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(12):841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, et al. Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(1):30–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, et al. Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: A randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni J, Amico K, Pearson C, Malow R. Strategies for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the literature. Curr Infect Disease Rep. 2008;10(6):515–521. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, et al. Effect of patient navigation with or without financial incentives on viral suppression among hospitalized patients with HIV infection and substance use: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(2):156–170. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loewenstein G, Brennan T, Volpp KG. Asymmetric paternalism to improve health behaviors. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2415–2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Friedman JY, Melichar LA, Volpp KG. Can behavioural economics make us healthier? BMJ. 2012;344:e3482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Behavioral economics holds potential to deliver better results for patients, insurers, and employers. Health Aff. 2013;7:1244–1250. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volpp KG, Pauly MV, Loewenstein G, Bangsberg D. P4P4P: An agenda for research on pay-for-performance for patients. Health Aff. 2009;28(1):206–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angeletos G, Laibson D, Repetto A. The hyperbolic consumption model: Calibration, simulation, and empirical evaluation. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15(3):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashraf N, Karlan D, Yin W. Tying Odysseus to the mast: Evidence from a commitment savings product in the Philippines. Q J Econ. 2006;121(2):635–672. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryan G, Karlan D, Nelson S. Commitment devices. Annu Rev Econom. 2010;2(1):671–698. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giné X, Karlan D, Zinman J. Put your money where your butt is: A commitment contract for smoking cessation. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2010;2(4):213–235. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers T, Milkman KL, Volpp KG. Commitment devices: Using initiatives to change behavior. JAMA. 2014;311(20):2065–2066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royer H, Stehr M, Sydnor J. Incentives, commitments, and habit formation in exercise: Evidence from a field experiment with workers at a Fortune-500 company. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2015;7(3):51–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volpp KG, Galvin R. Reward-based incentives for smoking cessation: How a carrot became a stick. JAMA. 2014;311(9):909–910. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nokes K, Johnson MO, Webel A, et al. Focus on increasing treatment self-efficacy to improve human immunodeficiency virus treatment adherence. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(4):403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]