Abstract

Purpose

To describe the rationale, methodology, design, and interventional approach of a mobile health education program designed for African Americans with end stage renal disease (ESRD) to increase knowledge and self-efficacy to approach others about their need for a living donor kidney transplant (LDKT).

Methods

The Living Organ Video Educated Donors (LOVED) program is a theory-guided iterative designed, mixed methods study incorporating three phases: 1) a formative evaluation using focus groups to develop program content and approach; 2) a 2-month proof of concept trial (n=27) to primarily investigate acceptability, tolerability and investigate increases of LDKT knowledge and self-efficacy; and 3) a 6-month, 2-arm, 60-person feasibility randomized control trial (RCT) to primarily investigate increases in LDKT knowledge and self-efficacy, and secondarily, to increases the number of living donor inquiries, medical evaluations, and LDKTs. The 8-week LOVED program includes an interactive web-based App delivered on 10” tablet computer incorporating weekly interactive video education modules, weekly group video chat sessions with an African American navigator who has had LDKT and other group interactions for support and improve strategies to promote their need for a kidney.

Results

Phase 1 and 2 have been completed and now the program is currently enrolling for the feasibility RCT. Phase 2 experienced 100% retention rates with 91% adherence completing the video modules and 88% minimum adherence to the video chat sessions.

Conclusions

We are in the early stages of an RCT to evaluate the LOVED program; to date, we have found high tolerability reported from Phase 2.

Keywords: Disparities, living donation, kidney transplantation, organ donation

1. Introduction

Kidney transplantation is the optimal treatment option for those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Transplantation outcomes include better quality of life and reduced disability, as well as long-term mortality rates that are 48% to 82% lower than those receiving dialysis [1–3]. Thus, it is critical to assist those with ESRD to receive a kidney transplantation as soon as possible due to costs and increased risk of mortality. This is especially important when considering the burden of kidney disease on minorities [4, 5]. In prior years (i.e., 2011 to 2015), 85,187 patients have received kidney transplantations in the United States via of one of two methods, deceased donor kidney transplant (DDKT) and living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) (based on Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) data as of October 3rd, 2016). DDKT is the receipt of a kidney from a recently deceased individual and represented 66.8% of all kidney transplants from 2011 to 2015. LDKT is the receipt of a kidney from a living individual which represents 33.2% of all transplants over the same time frame [6]. LDKT is superior to DDKT with improved graft survival, lower patient mortality while reducing wait-time to kidney transplantation [7, 8]. To illustrate the disparities issue, African Americans experience ESRD at 3.5 times the rate of Whites [9]. Marked differences are also found when comparing proportions of LDKT of African Americans to White groups (16.5% vs 43.9%) (based on OPTN data as of October 3rd, 2016). Together these data show that not only are African Americans disproportionally affected by ESRD but few receive LDKTs showing a clear need for interventions to address this health disparity [10].

Many transplant centers routinely hold educational sessions for eligible transplant recipients to increase patient knowledge. However, to enable patients, especially African Americans, to approach others and successfully find people to be evaluated for living donation, a larger emphasis on cultural barriers may be needed. Studies using a patient navigator or community health workers have shown promising results to increase potential donor (PD) initial inquiries and screenings [11]. Moreover, kidney transplant waitlist patients often face barriers to care (e.g. scheduling conflicts, transportation, cost, time, childcare, etc.) that limit access to such services or limit travel for group education classes. Other programs that are based closely around metropolitan areas of transplant centers have been effective in addressing some of these barriers by bringing nurse health educators and social workers into patient homes, but this approach may exclude patients who live in excessively outlying regions and could be resource intensive and cost prohibitive [12, 13].

Mobile health (mHealth) technology presents a potential solution to educate patients and teach skills through video education sessions, text messaging, and distance counseling approaches with one-on-one or group meetings. For this reason, we decided to capitalize on such technological advances to develop a mHealth, scalable intervention to engage patients to eliminate transportation and other barriers. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to define the design and rationale of the Living Organ Video Educated Donors (LOVED) program that promotes LKDT in African American ESRD patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study overview

The overarching goal of the LOVED program is to increase LDKTs for African Americans using a patient- and provider-centered, iteratively designed framework. It utilizes a mHealth delivery system for 8-weeks using 10” computer tablets consisting of weekly education modules and group video chat sessions led by an African American LDKT recipient, hereafter referred to as the “navigator”. Main outcomes include developing a highly tolerable program to increase LDKT knowledge, attitudes on LDKT, and increasing patients’ self-efficacy to ask others to be evaluated as a kidney donor who may subsequent complete LDKT. The LOVED program will serve to not only prompt the request but to educate the patient to inform PDs on a wide range LDKT topics (e.g., the testing and surgical process, their rights, financial issues, living with one kidney, etc.). The 5-year study is considered clinical research and is being executed in three iterative phases to increase its efficacy (see Table 1) including 1) a formative needs analysis using focus groups followed by program development, 2) a 1-arm proof of concept study using the LOVED program and subsequent refinement, and 3) a feasibility randomized controlled trial (RCT) using the LOVED program across the state of South Carolina. At this time, Phase 3 is being conducted.

Table 1.

LOVED Aims and Structure

| Phase 1 | Formative analysis | Conduct 9 total focus groups using: i) LDKT recipients; ii) LDKT donors; iii) ESRD patients who declined to approach potential donors (PDs); and, iv) transplant healthcare providers/staff. |

|

|

||

| Program Development | ||

|

| ||

| Phase 2 | Proof of Concept (n=27) | 2a. Conduct an 8-week single-arm proof of concept trial with African American ESRD patients (0–10 years on dialysis) to assess intervention fidelity, tolerability (% adherence, % drop out), and increases in LDKT related knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy at baseline and 8 weeks. |

| 2b. Conduct post-trial interviews/focus groups with: 1) navigators and providers; 2) LOVED participants to assess facilitators/barriers, attitudes/behaviors, cultural competency, and feedback on mHealth, navigator, and supportive components for LOVED optimization. | ||

|

|

||

| Program Iterative Development and Refinement | ||

|

| ||

| Phase 3 | Feasibility Trial (n = 60) | 1a. Conduct a 6-month feasibility RCT with African American ESRD patients (0–10 years on dialysis) comparing LOVED to standard of care (SOC) to assess feasibility indices of % adherence, % drop out and increases in knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy at baseline, 8-weeks and 6 months. Secondary outcomes are % of patients who identify PDs, and % of those who elect to be screened, and % who complete LDKT. |

| 2b. Conduct post-trial focus groups with: i) navigators/providers/staff; ii) random sample of 15 ESRD patients who received LOVED to assess facilitators/barriers, cultural competence, and recommendations for LOVED refinement. | ||

Phase 1 used a formative approach prior to the initial program development and incorporated data from focus groups consisting of LDKT and DDKT recipients, living donors, PDs, and providers in the medical profession. Focus groups were used to assess perceptions and knowledge of living donation, prevalence of technology ownership and utilization and familiarity and tolerance when using mobile devices for education purposes. The qualitative approach assessed focus groups’ transcripts and developed themes investigating various attitudes, barriers, and knowledge gaps of LKDT for the development of how video education components should be received and structured that encourages program use without overburdening the user. Cultural tailoring of the education modules and other program elements were reviewed by a panel of African American ESRD patients to ensure content was appropriate and culturally sensitive. The results from the Phase 1 have been previously published elsewhere [14, 15]. Findings aided in the development of the LOVED program’s format and content to dispel myths, increase knowledge, introduce skills and provide discussion topics [10, 16–20].

Phase 2 consisted of a locally recruited, 1-arm proof of concept study to assess the delivery of the first iteration of the LOVED program. Four waves consisting of 5–9 participants each, for a total of 25 African American adult ESRD patients were enrolled. The 8-week program used weekly video education modules along with peer navigator-led group mentoring sessions using video chat features (VidyoDesktop/VidyoMobile™) on supplied computer tablets (i.e., Samsung Galaxy Tab 2). After the program’s completion, focus groups provided feedback that clarified learning points and were used to refine educational modules and navigators’ educational delivery.

Phase 3 then used the reiterated LOVED program in a statewide 2-arm RCT with 60 African American adult ESRD patients (i.e., 30 in a LOVED arm and 30 in a standard care arm). Phases 2 and 3 will report usage statistics (i.e. dropouts, % modules watched, % chat session attendance) to assess the feasibility and tolerability of the program along with pre- and post-study surveys to assess attitudes, knowledge, and willingness (i.e., self-efficacy) to ask others for a LDKT. Phase 3 focus groups will aid in additional feedback to design a multi-site large-scale RCT using the LOVED program. Additional follow-up surveys in Phase 3 will be sent at 6-months post-baseline to assess retention of program knowledge in addition to number of living donor referrals, donor assessments and LDKTs.

2.2 Theoretical development overview

The LOVED program was informed by several behavioral change theories, technology acceptance models and the Multimedia Learning Theory [21–25]. The incorporation of these models and theories guided program development to address participants’ needs, prescribe an acceptable dosage and to select the medium of content delivery that will promote understanding of core concepts, increase the retention of program elements and enhance the usability of the program.

Theoretical constructs from the Self-Determination (SDT) [24], and Social Cognitive (SCT) [25, 26] Theories guided the behavioral content to address the “what”, “how” and “why” of behavior change and maintenance strategies. Self-efficacy and competence for behavior change are critical mediating constructs of SDT and SCT, but SDT additionally posits that confidence and competency are inadequate for facilitating behavior if motivation does not exist. To address this concept, SDT focuses on the processes through which one acquires motivation for initiating and maintaining behaviors over time and contends that developing a sense of autonomy and competence are critical [27], The People, Activity, Context and Technology Approach framework guided the approach toward technology usability to augment users’ perceptions to feel at ease with technology so they perceive the program as relevant and useful for their desired goal [23, 28]. For this reason, segments of the video modules were devoted to encouraging participants to perform the behavior and introduce relevant skills that are reinforced in the navigator chat sessions by providing opportunities to role play and practice speaking about their need for a LDKT (e.g., 1-minute backstory about their need, when and how to follow through, one-on-one versus group setting, etc.). The increase in accountability by requiring live video chat sessions was designed to promote follow-through to learn these skills and to build the social component of the program.

The development of the framework for the program elements of LOVED also leveraged the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. This theory posits that information should be structured on learning principles as opposed to the limits of specific technology [29]. Particularly, considerations of working memory [30] and cognitive load [31] strengthened the idea to utilize short video modules to disseminate learning points (e.g., dispel prevalent myths, learn the processes of transplantation, etc.). Further information on these concepts is not in the scope of this article but can be found elsewhere [22]. Overall, this strategy informed the development team to incorporate a series of short video clips with reinforcement quizzes covered over several weeks so participants would not be overwhelmed with too much information given at once, as is typically done in center-based programs. Distractions in videos were kept to a minimum by focusing on speakers and minimal use of other footage, thereby reducing extraneous cognitive load by focusing mostly on interviews using simple bullets during key moments. Learner control [21] was emphasized by the design of the app to allow the participant to pause and replay video segments so that they may move forward at their own pace. Choosing to break learning segments over a set number of weeks enables learners to reduce cognitive load by distributing material over time [31, 32]. This allowed the users to assimilate the knowledge in an asynchronous (i.e., at any time after the last week’s chat session until the next scheduled chat session; typically in 1 week) and methodological pattern (i.e., knowledge and skills build from week 1–8). Primary themes identified from the formative analysis were used to inform the creation of the weekly video sessions and served as the focus of the weekly chat sessions.

2.3 Sample

The LOVED program is designed for African Americans who are eligible for kidney transplantation and have not been able to identify a living kidney donor. This includes preemptive and former deceased donor transplanted patients. Phase 1 consisted of a convenience sample of African American deceased and living donor recipients, living donors, caretakers, and medical university transplant providers. Phase 2 and 3 inclusion criteria consisted of African American men and women between the ages of 18 to 65 years, who were preemptive or have had <10 years of dialysis treatment, were legally competent, were able to use a cell phone or tablet computer after instruction is given, and were active on the kidney-only transplant wait-list (i.e., multiple organ waitlisted patients were not included). Exclusion criteria included current substance use problems identified by transplant center providers or any persistent major psychiatric illness. Specific sampling targets vary per study phase discussed below. Before approaching patients, all recruitment and intervention practices were approved by the University’s ethical internal review board. Initial contact with potential participants were made through the transplant center’s transplant coordinator staff using approved patient contact scripts with follow-up calls made by research staff.

2.4 Protocols

2.4.1 Development of focus groups: Study Phase 1

Development of focus groups materials was predominantly derived from literature reviews and a series interdisciplinary team meetings, consisting of health behavior researchers, transplant surgeons and transplant coordinators with guidance from mHealth researchers from the Medical Center’s Technology Applications Center. Topics focused on attitudes and barriers associated with asking others for a LDKT among African American patients. There are many barriers that may contribute to the disparate trends regarding African American LDKT rates. Prior findings describe associations between low willingness to inquire about living donation and lower income status, medical distrust, financial misunderstanding on how the transplant is paid for, myths and beliefs about needing two kidne ys for optimal health, and other misrepresented concerns for the PD [10, 16, 17, 20, 33–36]. Other reasons include a lack of knowledge on the process of LDKT for the donor and lack of communication skills on how to initiate and follow-up on asking for a kidney [19, 37].

Guided by the behavioral theory-based motivational constructs previously mentioned, the basic structure for the LOVED intervention components were identified and created to guide the initial module components (Table 2) and focus group questions. Qualitative experts then finalized the target areas and scope of the questions. The acceptability of technology use was pretested using African American and other minority populations through templates and video demos.

Table 2.

Initial Module Content that Guided Development

| Barrier (theoretical content) |

LOVED Module Content | Navigator Role |

|---|---|---|

| Concerns about Potential Donors (PD) with a chronic condition (Motivation for change) | ESRD patients will play an educational “pick the donor” game where they will select an eligible donor from a list of video vignettes. Vignettes will include physically fit donors and donors with chronic health problems. The vignettes will be tailored to the health conditions present in the patient’s family to increase relevance. | Help ESRD patient identify eligible donors from their social network. |

| Burden operation would place on donor (Motivation for change) | Video “testimonial” content will be created that features LDKT donors speaking about their experiences with the process. Videos will provide corrective information about the misperceptions that often make ESRD patients unwilling to identify PDs & complete a transplant. | Address specific worries patients have about their identified PDs. |

| Mistrust of the medical community (Autonomy Motivation for change) | Video “testimonial” content will include LDKT donors and recipients speaking specifically about their experiences with medical staff during their transplant process. These commentaries will include both positive and negative experiences to minimize bias. | Speak with ESRD patients away from a medical setting. |

| Physical hardship after surgery (Autonomy Self-Efficacy) | A myth buster style game will address patients’ concerns about surgery. Patients will determine if a fact about the LDKT process is true and then given corrective information (e.g. “Transplant recipients are unable to have children after the surgery”). | Provide patient specific information about recovery. |

| Religious Concerns (Autonomy Motivation for change) | “Testimonial” content will include discussions with religious figures about the need for LDKT and from past LDKT receipts about the role faith played in their process. | Discuss the role of faith in the LDKT process. |

| Limited skills to approach PDS for LDKT (Self-Efficacy) | An interactive “role play” tool will guide the patients through several different scenarios in order to provide practice with approaching PDs. Patients will be given feedback about different strategies and encouraged for their choices. | Role plays with ESRD patients in approaching identified PDs. |

| Fear donors would regret their decision (Motivation for change) | Video “testimonials” of prior LDKT donors speaking candidly about their experience will be provided to ESRD patients. Topics will include benefits of their experience and regrets to give patients an honest portrayal of the LDKT process from the donor’s perspective. | Share personal stories and benefits about LDKT. |

| Financial Cost of Operation (Self-Efficacy) | A “guess the cost” tool will guide patients through the costs of the LDKT procedure for both the patient and the donor. Patients will estimate costs and given corrective feedback. | Give specific information for reimbursement plan. |

2.4.1.1 Phase 1 recruitment

In Phase 1, the recruitment structure used the transplant center’s records and transplant coordinator staff to make initial contact and to coordinate the focus group meetings. The registry used the entire state of South Carolina for the pool of eligible participants.

2.4.1.2 Phase 1 formative focus groups

A doctoral-level researcher experienced in qualitative interviewing led all focus groups. In addition, a research scribe who attended the focus groups showed a demo of a sample 1- minute video module and took verbal and non-verbal reactions during the sessions. Surveys were given at the beginning (i.e., living donation knowledge and perceptions) and end (i.e., mHealth use) during the focus groups. The focus groups took place on the MUSC campus (n=8) or through a conference call (n=1) setting. All focus groups were transcribed verbatim and examined by a qualitative analyst. Nine focus groups were originally defined to identify components for the program. The samples in the focus groups were as follows: 2 focus groups with LDKT recipients; 2 focus groups with DDKT recipients; 2 focus groups with living kidney donors; 2 focus groups with PDs/caretakers; and 1 focus group with providers. These groupings had been agreed upon by the research team after much deliberation to give a vast range of perspectives on the living donor and kidney donation process to identify the needs of LDKT recipients’ PDs and capture common questions that are asked of providers. At the conclusion of these collective discussions, the results gave direction to identify culturally sensitive strategies (e.g., promoting trust, communication, shared decision making) to facilitate LDKT.

2.4.1.3 Phase 1 formative analysis

The qualitative analysis for all focus groups used grounded theory using NVIVO 10.0 (QSR International, Pty, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). This entailed using a hybrid analysis including inductive and deductive methods to develop taxonomy and themes that became the basis of the video module education content and discussion points during video chat sessions [38]. Two researchers reviewed the transcripts in a line-by-line method and code responses to form a set of themes until [39]. Refinement of coding results were performed through methods of immersion and crystallization by two researchers and non-verbal observations from the focus groups [40]. Surveys were used to contrast against the qualitative results and included additional topic areas focus groups may not have included (e.g. other common myths, barriers, acceptance and perceptions mHealth). All data were combined and contrasted to report study outcomes.

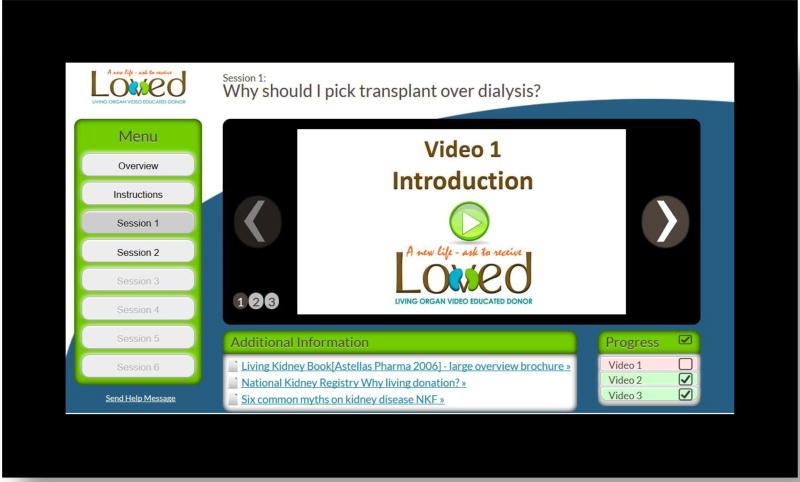

2.4.2 LOVED program development

From Phase 1’s results, LOVED was developed as an 8-week program. Identified themes and subthemes were used to initiate program development content. Weekly content included 8 video chat sessions and 6 web-app delivered video education modules where the first 4 modules would be delivered consecutively and the remaining 2 delivered every other week. This allowed participants additional time to develop strategies, gain feedback, and practice skills to express their need for a kidney during the weekly video chat sessions. Each module was accessed through the LOVED web-app and was defined with a central theme with several sub-themed video segments. Each sub-theme consisted of educational topics the research team felt ESRD patients should know based on the formative results. For instance, in week 3, the central theme is “Who qualifies to be a living donor”? Subthemes were then developed each with a descriptive video using physician surgeons, social workers, prior LDKT recipients, nursing researchers and caretakers (i.e., Video subthemes 1: Who can you ask? (matching and testing criteria, initial evaluation steps for PD qualification, message to let physicians decide who can donate so ask everyone); 2: Who can donate? (e.g., topics of age, race, diabetes, hypertension, selection committee decision); and 3: Overcoming your barriers to ask (e.g., preparing yourself mentally, mindset on who is eligible to donate, educate yourself). Additional resources were provided for each module to provide additional examples and patient stories pooled from other sources. The LOVED web-app interface was designed using the theories previously mentioned for technology use and multimedia learning. During development, creation of 3 brief 2- to 4-minute videos were made for each of the 6 modules using short segments from physicians, transplant center staff and testimonials from LDKT recipients, living donors, caretakers and community leaders that varied by topic (See Figure 1 for an illustration of the interface). Integrated questions after each video tested understanding of key education topics. The delivery form factor used a cellular connected 10” tablet computer (i.e., Samsung Galaxy Tab 2) to provide video feeds during chat sessions while standardizing the experience using the LOVED web-app. The LOVED program application was accessed by a web-link using registered usernames and passwords. Shortcuts to the LOVED program app and video chat links were placed on the tablet home screen for direct access. Video chat discussion topics were created from the weekly education module topics. Navigator training consisted of a series of intensive training workshops with transplant center and study staff to ensure interpersonal skills, group guidelines and relevant content knowledge when leading the group video chat sessions.

Figure 1.

LOVED program application screenshot

2.4.3 LOVED intervention components

The LOVED application includes three primary intervention components: 1) weekly education modules delivered via a web-application available for use on tablet computers, 2) weekly group-based navigator-led video chat discussions, and 3) supportive interaction with navigator and other group members (i.e. chat rooms, phone calls, text messaging, etc.). Details of each component are discussed next.

2.4.3.1 Education modules

Modules will directly address key barriers with respect to LDKT while providing education about the donor process to correct misperceptions on LDKT knowledge. The intention of the education modules is to prepare participants to discuss topics related to LDKT during the video chat sessions to clarify the education content and prepare them to openly discuss these topics with PDs. Education modules themes and discussion topics are found in Table 3. Each module has a primary theme, 3 education videos and a set of additional resources. Participants are allowed to watch videos multiple times at their own pace though they are not allowed to fast forward during the first viewing. The modules are paced in a weekly format where modules are slowly released throughout the 8-week program (e.g., the module for week 2 will be released immediately after completion of week 1’s video chat session). Participants are expected to complete the current week’s module prior to the next video chat session.

Table 3.

LOVED Weekly Module Central Themes and Navigator Discussion Topics

| Week | Weekly Tablet-Based Video Education Module Themes |

Navigator Video Chat Session Topics Discussion Topics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1: What is transplant like for the recipient? | 1 – Your story, recipient’s transplant process |

| 2 | 2: What is donation like for the donor? | 2 – Knowledge on donor process Q&A |

| 3 | 3: Who qualifies to be a living donor? | 3 – Who can you ask, eligibility |

| 4 | 4: Communicating your need | 4 – Strategies to ask others |

| 5 | No module assigned | 5 – Practice asking, methods to get the word out |

| 6 | 5: Expectation of Support | 6 – Forming your support system, Finding caretakers and advocates |

| 7 | No module assigned | 7 – Practice asking, methods to get the word out, list out your support system |

| 8 | 6: Motivation for Action: Get the ask out | 8 – What is life like after transplant, keeping motivated, Q&A |

2.4.3.2 Navigator discussions and interactions

Navigators will lead 8 weekly group video discussions to review the weekly module content, address group questions, and facilitate conversations among group members. Since navigators have received a LDKT, they will be able to relate to the experiences and emotional perspective of the participants. Participants will be able to directly contact navigators through LOVED via video or phone chat about their concerns, questions, or clarifications on topics involving LDKT. These conversations could include addressing specific concerns about the process (e.g., what will my recovery time be?) or practice specific skills (e.g., role play how to ask a PD). The video chat sessions will be recorded by study staff to assure predefined education topics have been covered by each navigator.

2.4.3.3 Role of interactive support features

Participants will be allowed to contact each other through LOVED to privately discuss their experiences and provide support to one another. Use of self-directed components including chat rooms, text/email exchanges between group members and/or navigator could occur if desired. The focus groups throughout the studies will further inform preferences for additional contact well as other components in the LOVED intervention to provide support.

2.4.4 Phase 2: Proof of concept study

2.4.4.1 Scope of Phase 2

Phase 2 used a single arm study using kidney transplant wait-list patients who live within 60 miles of the transplant center and were available to attend in-person orientation. Four groups using two navigators were completed with 25 total participants. Participants were provided free cellular network connected tablet computers for the duration of the study to remove technology ownership barriers such as lack of a tablet computer of their own, or not having a computer with broadband internet. All participants were invited to give feedback through in-person focus group sessions upon completion to elicit feedback on the program.

2.4.4.2 Phase 2 recruitment

The LOVED program seats approximately 6–10 kidney wait-listed participants per group. Phase 2 used a sample from the immediate area in and around Charleston, South Carolina within 60 minutes of the University meeting location. Four groups were recruited from transplant center wait-list records by transplant center staff with a goal of 27 participants.

2.4.4.3 Phase 2 sample size determination

Primary intervention outcomes using mean % tolerability (i.e., % adherence to both video chat sessions and completion of video modules; % drop out rate) and primary patient-level changes in LDKT related knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy pre- to post-study with 24 subjects per trial will provide 80% power to detect at least a 0.60 standardized (sd units) effect size using a one-group t-test (level of significance [α]=0.05, two-tailed). Secondary outcomes include % ESRD patients who identify PDs and % PDs who complete screening and donation. Secondary outcomes pertaining to the number of PD evaluations and % of PD completing LDKT, are based on a one-group χ2-test (α=0.05, two-tailed) with 24 participants will provide at least 80% power to detect a difference between the null hypothesis and alternative proportions (estimates are based on Rodrigue et al. [41, 42]). We expect a 10% drop out rate based on our previous transplant clinical trial studies [43] so 27 participants were used as the targeted enrollment for this phase. For the qualitative component, based on previous studies [44] we expect 12 key informant interviews to be sufficient to provide common experiences of subjects, along with variations in participants’ perceptions necessary to identify outliers [45].

2.4.4.4 Phase 2 measures

Primary intervention outcome variables are fidelity and tolerability of the LOVED program (i.e., % adherence to chat sessions; % module completion; % drop out rate). Primary patient level outcome variables are changes in LDKT knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy toward LDKT. This study was not designed to determine the optimal dose but rather used literature reviews, expert opinion, and theory-based patient-guided iterative design to enhance tolerability. Participant outcomes will be measured pre- and post-study (i.e., 3 months) using: 1) LDKT Knowledge Scale (15 item T/F) 2) LDKT Concerns Scale (attitudes) (21 T/F) and 3) Willingness to Discuss LDKT Scale (efficacy) (1 item 7 pt. Likert scale).[13, 46] Response burden is acceptable at 15–20 minutes. Adjusted mean change (adjusted for covariates such as age, gender, education, etc.) and corresponding 95% CIs will be obtained using GLM approaches. Mean change in LDKT knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy within the two groups pre- to 6 months will be estimated via 95% CI. At the post-study evaluation, subjects will also complete a Likert-scale survey that will assess satisfaction and barriers/facilitators of adherence and intervention cultural competency.

All participants were invited to participate in focus groups of their “lived experiences” as a LOVED participant. Topic areas covered LDKT expectations, experiences, adherence, motivation, advice from advocates, and culturally competency (trust, shared decision making, etc.). Audio recordings were transcribed and analyzed with qualitative approaches using NVivo 10.

2.4.4.5 Iterative development between Phase 2 and 3

Between Phase 2 and 3, the LOVED program was iterated upon using Phase 2 focus groups’ feedback to guide new video educational content, additional resources, and changes to the navigator discussion topics. The Phase 2 focus groups primarily provided insight on additional myths and topics needing additional clarity (i.e., number of sessions, connectivity or hardware issues, beliefs that kidneys will eventually regenerate). Changes to program delivery included earlier introduction of skills training for patients to prepare and practice asking for a kidney during the video chat sessions, additional extra resource links in the education modules and a redeveloped video from a physician stating that kidney damage is permanent and the body cannot self-heal.

2.4.5 Phase 3: Feasibility RCT

2.4.5.1 Scope of Phase 3

Phase 3 was designed as a RCT with a sample size of 60 and will compare the LOVED (n=30) against a standard care arm (n=30). The LOVED arm followed the protocol of the LOVED program. The standard care arm incorporated usual care provided by the MUSC transplant center including wait-list candidate transplant center coordinators and education material (i.e., brochures, handouts) provided by the center. All wait-list patients attend an in-person 2-hour transplant education seminar about kidney transplantation including DDKT and LDKT prior to being waitlisted for kidney transplantation. Baseline, post-study (i.e., 3 months) and 6-month follow-up measures will be completed to assess retention of knowledge and attitudes toward LDKT using mailed or an encrypted emailed survey response system. In addition, post-study and 6-month review of transplant center records will assess the number of referred PDs, how many of those completed the evaluation process and the proportion of those who subsequently completed a LDKT. Due to the location of participants across South Carolina, each of the LOVED-only arms will be invited to a post-study online video chat focus group session to collect program feedback.

2.4.5.2 Phase 3 recruitment

Phase 3 incorporated a sample that encompassed all geographic locations in South Carolina. Eligible patients were contacted by phone by transplant center staff then followed up by study staff where informed consents were mailed and returned before entry into the study. Computer randomization stratified by gender was used to assign participants into standard care or LOVED arms so approximately equal numbers of male and females were represented in each arm. Four LOVED groups were planned in groups of 6–10 each.

2.4.5.3 Phase 3 sample size determination

Sample sizes were designed to obtain estimates of variability for the primary outcome measures and to obtain preliminary indicators of treatment effectiveness as necessary input for the design of a future efficacy/effectiveness RCT. Therefore, sample size justification focuses on precision of estimates rather than power of statistical tests. For the categorical outcome measures, using an intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses, with 30 participants per group was used and allows estimated outcome proportions with precision values of ±0.11 to ± 0.16 for p-values ranging from 0.10 to 0.30. For the continuous primary outcome measures, using an ITT analyses, with 30 participants per group, 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates of the mean % tolerability over the study intervention and the within-group change in LDKT knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy from pre to months 1, 3, and 6, will have precisions ranging from ±0.18 to ±0.90 corresponding to estimated standard deviation (SD) of LDKT knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy change ranging from 0.5 to 2.5, respectively. The between groups difference in changes can be estimated with precision ranging from ±0.18 to ±0.76 for SDs of scale score difference ranging from 0.35 to 1.5 SD units. Assuming a 10% drop out rate based on our previous transplant clinical trial studies[43] with 27 participants per group, 95% CI estimates of the difference between group change in scores (pre to months 1–6), we will have precisions ranging from ±0.19 to ±0.80 (±0.16 to ±0.69), corresponding to estimated SDs of change ranging from 0.35 to 1.5, respectively. Preliminary hypothesis test of between group comparison of differences in changes in the 3 LDKT scales will have 80% power to detect a difference of 0.74 (0.63) SD units (based on 2-sided pooled t-test comparison with α=0.05).

2.4.5.4 Phase 3 measures

Primary outcome measures will use mean adherence and changes in LDKT knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy measured at pre-intervention, to 6 months as in the Phase 2 proof of concept study [13, 46]. For primary continuous measures, pre- to 6-month changes (effect sizes) will be estimated via 95% CIs. Adjusted mean change (adjusted for covariates such as age, gender, education, etc.) and corresponding 95% CIs will be obtained using the GLM approach. Mean change in LDKT knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy within the two groups pre- to 6 months will be estimated via 95% CI. Secondary outcome measures are the proportions and differences in proportions of ESRD patients who identify PDs and % PDs who complete screening and % who donate a kidney estimated via 95% CIs. For end-of-study efficacy outcomes, we will impute missing 6 months data via multiple imputation methods using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA) [47]. If >10% of data are missing, we will consider adding an intermediate measurement point for the primary outcomes in the future RCT to provide additional information for use in endpoint imputation.

Feasibility measures include recruitment and tolerability (% agreed to participate out of those approached, % adherence to sessions, % drop out). Further, reasons for non-adherence and discontinuation of treatment, and problems/issues encountered with the intervention will be des cribed from focus group data using a qualitative approach. Post-study focus groups were conducted using the video chat feature of the LOVED program with the LOVED arm participants to elicit program feedback, transcribed and evaluated using NVivo 10.

2.4.6 Technology use analytics for Phase 2 and 3

Monitoring and reporting of LOVED web-app use analytics will be performed. Reporting includes the number and timing of watched videos, the count and time of when videos and resources were accessed and video quiz scores. These will be reported in the analysis of Phase 2 and 3 acceptability and tolerability results.

2.4.7 Overview Phase 2 and 3 analyses

Sample distributions will be evaluated to ensure distributional assumptions underlying the proposed statistical tests are met. Main outcome statistics are described previously. If assumptions of parametric procedures are violated, appropriate nonparametric analogs will be used (e.g., Wilcoxon signed ranks test). Descriptive statistics will be calculated for all variables, including demographics, as appropriate. Univariate descriptive statistics and frequency distributions will be calculated, as appropriate using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA).

Results of Phase 2 and 3 focus groups who received LOVED will be analyzed using methods described previously to explore attitudes, beliefs, barriers and facilitators for use, as well as feedback on recruitment, retention, fidelity (e.g., how is the study introduced to participants, pertinent instructions for LOVED implementation, adherence to modules and videoconference and chat room sessions, etc.).

2.5 Potential risks

Potential risks from the LOVED studies represent minimal risk. All study data collection procedures (i.e., questionnaires) are noninvasive. All procedures will be explained and the identified questionnaires have been purposely selected, have established psychometric properties for the age range of the participants and can be completed with low user burden. There are no aspects of data collection procedures expected to bring physical discomfort. In the unlikely event of an adverse event during the participant’s visit, he/she will be already be present in his/her personal physician/provider’s practice.

3. Results

Findings from the focus groups in aim one [14, 15] have been used to develop the video education modules and develop education materials for the navigators and program elements. Results showed initial high acceptability on the LOVED program concept. Preliminary results from Phase 2 showed 100% retention rates in all groups, 91% adherence to completing the video modules, 88% minimum adherence to the video chat sessions suggests strong tolerability. Patients reporting high acceptability using LOVED to provide them support in their need for a LDKT. Two participants from Phase 2 are entered in the paired-exchange process for LDKT. At the time of this report, Phase 3’s feasibility RCT is currently in process.

4. Discussion

The LOVED study intends to increase the number of living donor kidney referrals, medical evaluations and eventually increase the rates of LDKT of African Americans in South Carolina. Leveraging mHealth communication and education technology, patients from various disparate locations can form small supportive groups, learn how to strategize the best way to market their need for a kidney and increase self-efficacy to ask others for a LDKT. Programs such as LOVED and other telehealth ventures are important to consider when reaching minority groups in remote locations. States such as South Carolina or other geographic areas where there are few transplantation centers, wait-list patients may be hundreds of miles away. Many dialysis patients may be hindered by the lack of access or ability to afford transportation to complete face-to-face meetings at transplant centers or in patient homes. Furthermore, many wait-list candidates also work, have family responsibilities, and have limited time to meet on a routine basis for in-person group meetings. The LOVED program may be a feasible alternative to transplantation center-centric education sessions that inform patients about LDKT education. Though some patients may elect face-to-face interactions, our preliminary findings show this may be more of a want than a need to increase knowledge and improve their social support system resulting in increased ways to improve LDKT advocacy.

5. Conclusions

The LOVED program seeks to address barriers for African American ESRD patients seeking a LDKT. The design and execution of the LOVED program may be an important case study in the methodological considerations for other distance health education practices. These may include telehealth programs for other living donor organs such as liver, or inform other services such as motivational programs for coronary heart disease or stroke recovery. Besides improved life expectancy and quality of life for kidney transplant recipients [1–3], there is a large economic incentive as medical costs are much lower for transplanted patients as opposed to remaining on dialysis. It is the aim of the LOVED program to increase the longevity of African American kidney wait-listed patients while providing an economic benefit to the greater community through reduced costs of care.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure statement

We would like to give our sincere appreciation to the MUSC Transplantation Center, especially Phyllis Connor-Richey, Sarah Parker, BS, RN We would like to thank our navigators in the project, Everett German and Clifford Fullmore, Ph.D. and Ashley Anderson, BS who served as a Program Manager during the feasibility trial. Lastly, we would like to thank James Rodrigue, Ph.D for valuable input during the development of the project. This publication was supported with funding from NIH grant DK 098777 and the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (SCTR), with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina, Clinical & Translational Science Award NIH/National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), grant UL1RR029882. The content does not represent the official views of the NIH or the NCRR. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.”

Abbreviations

- LDKT

Living donor kidney transplantation

- DDKT

Deceased donor kidney transplant

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- LOVED

The Living Organ Video Educated Donors

- RCT

Randomized Control Trial

- mHealth

Mobile Health

- SCT

Social Cognitive Theory

- SDT

Self-Determination Theory

- LOVED program

Living Organ Video Educated Donors

- PD

Potential donor

- ITT

Intent-to-treat

- CI

Confidence interval

- SD

Standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkelmayer WC, et al. Health economic evaluations: the special case of end-stage renal disease treatment. Med Decis Making. 2002;22(5):417–30. doi: 10.1177/027298902236927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ichikawa Y, et al. Quality of life in kidney transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(7):1815–6. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra R, et al. Racial differences in mortality among those with CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(7):1403–1410. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feehally J. Ethnicity and renal disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(1):414–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarantino A. Why should we implement living donation in renal transplantation? Clinical nephrology. 2000;53(4):A55–A63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemati E, et al. Does kidney transplantation with deceased or living donor affect graft survival? Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6(4):e12182. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molnar MZ, et al. Age and the associations of living donor and expanded criteria donor kidneys with kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(6):841–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fast Facts. 2016 Apr; 2016 Nov 11, 2016]; Available from: https://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/factsheets/FastFacts.

- 10.Waterman AD, et al. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30(1):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marlow NM, et al. A patient navigator and education program for increasing potential living donors: a comparative observational study. Clin Transplant. 2016;30(5):619–27. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weng FL, et al. Protocol of a cluster randomized trial of an educational intervention to increase knowledge of living donor kidney transplant among potential transplant candidates. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:256. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigue JR, et al. A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: effects in blacks and whites. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):663–70. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sieverdes JC, et al. African American kidney transplant patients’ perspectives on challenges in the living donation process. Prog Transplant. 2015;25(2):164–75. doi: 10.7182/pit2015852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieverdes JC, et al. Patient-Centered mHealth Living Donor Transplant Education Program for African Americans: Development and Analysis. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(3):e84. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siminoff LA, Saunders Sturm CM. African-American reluctance to donate: beliefs and attitudes about organ donation and implications for policy. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2000;10(1):59–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigue JR, et al. Patients’ willingness to talk to others about living kidney donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):25–31. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunsford SL, et al. Racial differences in the living kidney donation experience and implications for education. Prog Transplant. 2007;17(3):234–40. doi: 10.1177/152692480701700312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterman AD, et al. Living donation decision making: recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arriola K, Perryman J, Doldren M. Moving Beyond Attitudinal Barriers: Understanding African Americans’ Support for Organ and Tissue Donation. J Nat Med Assoc. 2005;97(3):339–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer RE, Moreno R. Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson ID, Marsch LA, Acosta MC. Using findings in multimedia learning to inform technology-based behavioral health interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(3):234–243. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huis in ‘t Veld RM, et al. A scenario guideline for designing new teletreatments: a multidisciplinary approach. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(6):302–7. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentiss-Hall; 1986. pp. 1–617. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan R, et al. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on self-determination theory. The European Health Psychologist. 2008;10:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beynon-Davies P, Holmes S. Design breakdowns, scenarios and rapid application development. Information and Software Technology. 2002;44:579–592. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer RE. Multimedia Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baddeley A. Working memory. Science. 1992;255(5044):556–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1736359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweller J. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learn Instr. 1994;4:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plass JL, Homer BD, E H. Design factors for educational effective animations and simulations. J Comput High Educ. 2009;21:31–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunsford SL, et al. Racial differences in coping with the need for kidney transplantation and willingness to ask for live organ donation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(2):324–31. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weng FL, et al. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among black or older transplant candidates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2338–47. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill J, et al. The effect of race and income on living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1872–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purnell TS, et al. Measuring and explaining racial and ethnic differences in willingness to donate live kidneys in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(5):673–83. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnieh L, et al. Barriers to living kidney donation identified by eligible candidates with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(2):732–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigue J, et al. Increasing Live Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Home Based Educational Intervention. American journal of transplantation. 2007;7(2):394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodrigue JR, et al. A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: Effects in blacks and whites. American journal of kidney diseases. 2008;51(4):663–670. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taber DJ, et al. AMERICAN TRANSPLANT CONGRESS. Boston, MA: American Journal of Transplantation; 2012. Prospective Comparative Efficacy of Induction Therapy in a High-Risk Kidney Transplant (KTX) Population. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poland ML, et al. Quality of prenatal care; selected social, behavioral, and biomedical factors; and birth weight. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1990;75(4):607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poland ML, et al. Quality of prenatal care; selected social, behavioral, and biomedical factors; and birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(4):607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigue JR, et al. Increasing live donor kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial of a home-based educational intervention. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(2):394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]