Abstract

Background

Evidence on the treatment effectiveness for bilingual children with primary language impairment (PLI) is needed to advance both theory and clinical practice. Of key interest is whether treatment effects are maintained following the completion of short-term intense treatments.

Aims

To investigate change in select language and cognitive skills in Spanish–English bilingual children with PLI 3 months after children have completed one of three experimental treatment conditions. There are two main study aims. First, to determine if skills in Spanish, English and cognitive processing decline, improve or are maintained after treatment has been completed. Second, to determine if differential rates of change are a function of the type of treatment children received.

Methods & Procedures

Participants were 48 children, aged 5:6–11:3, who spoke Spanish and English and were diagnosed with moderate to severe PLI. Participants received 6 weeks of treatment focused on English only (EO), bilingual skills in Spanish and English (BI) or nonlinguistic cognitive processing (NCP). Treatment effects reported in a previous study were determined by comparing pre- and post-treatment performance on a variety of language and cognitive measures. Here we re-administered each measure 3 months after completion of the experimental treatments. Hierarchical linear models were calculated for each measure using pre-, post- and follow-up testing scores to estimate change trajectories and compare outcomes between treatment conditions.

Outcomes & Results

Participants in all three treatment conditions either maintained skills or showed improvement even after treatment was discontinued for 3 months. Main findings included (1) comparable, positive rates of change on all English language outcomes for EO and BI conditions; (2) maintenance of Spanish language skills, and (3) modest improvements in NCP following the discontinuation of treatment.

Conclusions & Implications

This study is the first to examine longer-term treatment effects for bilingual school-age children with PLI. Differences in rates of change between languages and between treatment conditions are discussed in terms of social and cognitive processes that impact children’s language systems. The main findings have at least two implications for clinical practice: (1) therapy that emphasizes focused practice in language and cognitive processing skills may promote gains in children’s language learning abilities; and (2) bilingual treatment does not detract from outcomes in English, the language of the majority community for study participants.

Keywords: English language learner, specific language impairment, growth trajectories, intervention

Introduction

In an era of limited resources within both educational and healthcare settings, it is unlikely that language treatment services can be applied on an indefinite basis. There is an urgent need to build treatment efficacy research that considers the longer-term effects of language treatment following the discontinuation of direct services. To date, few empirical studies examine treatment effects among school-age children with language impairment, and even fewer studies examine whether these effects are maintained after the completion of treatment.

Similarly, there is an urgent need to investigate language treatment effects in children who rely on two languages to meet their communicative needs. The number of children from immigrant families living in Western countries, including the United States, UK and Canada, has increased markedly over the past two decades (Paradis et al. 2010). Children of immigrants in these countries often need one language to communicate with parents and family members and English to be successful in school and the larger society. There is little empirical literature to date on language treatment efficacy within school-aged children who speak a minority language at home.

The present study contributes to the empirical literature by investigating change in language and cognitive processing skills in Spanish–English bilingual (BI) children with primary language impairment (PLI) 3 months after experimental treatments have been discontinued. In Ebert et al. (2014), we measured immediate effects of three distinct treatment conditions targeting English, Spanish and English, or NCP. Here we use statistical models that capture change over time to determine if En-glish, Spanish and cognitive processing skills increased, decreased or were maintained after the conclusion of treatment. In order to frame the current study, we first consider the expected trajectories of language growth for monolingual children with PLI as well as for typically developing sequential bilinguals.

Language growth for monolingual children with PLI

PLI is considered a chronic deficit in language skill in comparison with age peers, despite otherwise typical development. Longitudinal studies of monolingual English-speaking children with delayed language skills at school entry have shown that language deficits persist over time (e.g. Johnson et al. 1999). It is not yet clear whether children with PLI maintain a similar language growth rate to unaffected peers during the school years—resulting in a steady gap in language skill over time between the two groups—or if they gain language more slowly than typically developing peers and continue to fall further behind. Law et al. (2008) found the former pattern in an analysis of the receptive language growth of school-aged children with PLI: affected children began the school years with lower language skills and then continued to gain language skills at a rate comparable to unaffected peers. However, children in the study, who were part of the Manchester Language Study may have been receiving some language treatment during the years studied; the authors do not discuss the effects of any language treatment in their results. Similarly, Rice et al. (2009) document comparable growth rates in grammaticality judgment performance for school-aged children with and without language impairment; again, the presence or absence of language treatment services is not explicitly discussed. In sum, the limited literature on language growth of children with PLI during the school years suggests they are unlikely to catch up to unaffected peers, perhaps even with ‘treatment as usual’ over time.

It is possible that more effective, or more intensive, language treatment could accelerate language growth in school-aged children with PLI and allow them to narrow the gap. Most published investigations of language interventions for school-aged children with PLI have been limited to considering effects immediately after treatment, with the exception of two recent large randomized controlled trials (Boyle et al. 2009, Gillam et al. 2008). Boyle et al. (2009) examined the effects of intensive language treatment for 161 children, aged 6 to 11 years, in the UK. Treatment was administered directly or indirectly by a speech–language pathologist three times per week over 15 weeks, and post-treatment follow-up assessments were conducted 12 months later. All the intensive language treatment conditions resulted in immediate gains on a standardized measure of expressive language, with some advantage retained one year later compared to children who did not receive this programme. However, there was no continued growth on the dependent variables of interest after therapy had been discontinued. Moreover, children in the control group, who received ‘therapy as usual’, demonstrated no growth in standardized language scores across time, consistent with PLI as a persistent disorder and with the difficulty in inducing longer-term change for this group.

In a study conducted in the United States, Gillam et al. (2008) provided treatment to 216 children with PLI, aged 6–9 years who were randomly assigned to one of four different treatment conditions. Participants received intensive treatment over a 6-week period, with post-treatment follow-up testing at 3 and 6 months. Main findings included modest but statistically signifi-cant gains in language scores following the completion of treatment: average gains of 2 standard score points were obtained between immediate post-treatment and the 3-month follow-up and an additional 1.8 standard score points were gained between the 3- and 6-month follow-up time points. Thus, unlike Boyle et al. (2009), Gillam et al. (2008) found some evidence of ongoing growth after the conclusion of language treatment.

A myriad of variables may influence the longer-term effects of language treatment. Differences in participant age, the type and severity of language deficits, the duration and intensity of the treatment programme, and the length of time before follow-up testing is completed may all influence findings of longer-term language gains. Two important sources of variation warrant additional discussion here. First, the measures used to assess language change should be carefully considered: when the effects of language treatment are measured using standard scores from norm-referenced assessments, steady scores over time are an indication of continued language growth at a rate comparable to peers. Second, the treatment programme itself is an important source of variation in longer-term effects. Treatment programmes may of course be more or less efficacious in remediating a disorder. In addition, they vary in the proposed mechanism of action, which influences their expected longer-term effects. In general, treatment that addresses surface symptomatology may provide immediate relief from a condition, but require continued application to maintain effects. Treatment that addresses an underlying cause of a disorder may require more time to take effect, but might be expected to create a longer-term alteration in the trajectory of the disorder. In the case of PLI, a disorder in which the underlying causes are the subject of debate and the surface symptomatology is complex, this distinction is not completely clear. In addition, very different treatments have purported to address underlying causes (cf. computer software targeting rapid auditory processing described in Gillam et al. 2008; explicit work on verb argument structure described in Ebbels et al. 2007). Yet it is reasonable to hypothesize that effective remediation of underlying causes of PLI would lead to improved language learning in the longer-term.

One prominent hypothesis regarding the underlying cause of PLI is that subtle deficits in NCP skills—such as speed of processing, memory, and attention—contribute directly to the defining language weaknesses (Leonard et al. 2007). If these cognitive processing skills do indeed contribute to language learning, treatment that successfully improves them could lead to longer-term improvements in language skills. In the current study, NCP skills were measured alongside language skills, allowing us to consider whether immediate improvements in NCP influence longer-term growth in language.

First and second language growth in sequential bilingual children with and without PLI

Thus far, we have focused on language growth and treatment effects in monolingual children with PLI. Participants in the present study speak more than one language; they speak a minority first language (L1) at home and learn a second language (L2) upon entering preschool or kindergarten, making them early sequential bilinguals. Longitudinal studies with typically developing sequential bilingual school-age children have found rapid gains in the L2 and a shift in language dominance from the L1 to the L2 during middle childhood (e.g. Jia and Aaron-son 2003, Pham and Kohnert 2014). Rapid growth in the majority L2 is a consistent finding across studies and has been related to at least two factors in the school-age years: (1) higher social value attributed to the majority language and (2) increased opportunities to use the majority language for a wide variety of purposes (Kohnert 2013). In contrast, varied growth patterns in the minority L1 have been documented. Continued development of the L1 throughout the early school years is possible and has been found to be related to educational support for the minority language (Pham and Kohnert 2014). In cases of little to no L1 support in the school or community, L1 attrition has been found and can be defined as either a plateau of L1 skills or the loss of previously acquired skills (Jia and Aaronson 2003).

To date, we are aware of a single longitudinal study that includes school-age bilingual children with PLI. Salameh et al. (2004) compared grammatical development among bilingual Arabic–Swedish children, aged 4–7, who were typically developing (n = 10) or had PLI (n = 10). Salameh et al. (2004) found that all typically developing participants reached ceiling levels in the L1 and L2 by Time 3, while only three of 10 participants with PLI reached ceiling levels in both languages. Of the remaining, four of 10 showed incomplete grammatical acquisition in each language, two of 10 reached ceiling levels in the L2 only, and one of 10 reached ceiling level in the L1 only. Preliminary evidence indicates that bilingual children with PLI may be at a greater risk for L1 attrition than their typical peers (Salameh et al. 2004). While bilingual children with and without PLI face the same social factors such as limited opportunity to use the minority language, children with PLI interact with the social environment with a weakened language system (see Kohnert 2013 for a discussion). Consequently, language treatment that contributes to L1 maintenance or even small L1 gains may represent a significant improvement in the expected trajectory.

The present study: purpose and questions

The present study examines longer-term outcomes following treatment for sequential bilingual children with PLI. Previous language treatment studies (e.g. Boyle et al. 2009, Gillam et al. 2008) have used traditional repeated measures analytical approaches (e.g. ANOVAs). The present study calculates growth trajectories using hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) also referred to as growth curve modelling. Main advantages of HLM over traditional repeated measures approaches are the ability (1) to calculate rates of change (i.e. slope), (2) to extrapolate future change, (3) to include participants with missing data and (4) simultaneously to account for individual-level variability and group-level growth (Long 2012).

There are two main research questions:

Do targeted skills in Spanish, English and cognitive processing decline, improve or remain the same 3 months after the completion of treatment?

For the targeted skills that show change following the completion of treatment, is the change dependent on the type of treatment children received?

Ebert et al. (2014) found positive gains immediately after treatment on multiple measures of English and relatively fewer gains in Spanish and nonlinguistic cognitive skills. The present study examines whether these effects are maintained over time.

Method

A total of 48 children participated in this study (41 boys, 7 girls), ranging in age (years:months) from 5:6 to 11:3. Participants spoke either Spanish only or Spanish and English in the home and attended primary school in an urban setting in the United States in which English was the language of instruction. All participants were receiving school-based special education services and were classified as having moderate to severe PLI based on clinical referral and parental concern. Clinical referral was based on school district criterion of below age-level performance in both languages. Parental concern was with language and/or learning in the absence of other health concerns including hearing loss, autism, head injury, cerebral palsy, seizures, general cognitive delay, or physical disabilities (see Ebert et al. 2014 for further details on the classification process).

Participants completed treatment in small groups for 75 min/day, 4 days/week, for 6 weeks. Treatment sessions consisted of four to five activities of equal length, balanced between computer-based and interactive formats. Treatment was administered by speech–language pathologist at children’s schools, after school hours. All three treatment conditions were administered iteratively throughout the year.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: EO (n = 17), BI (n = 15) or NCP (n = 16). A fourth, deferred-treatment control condition, did not complete follow-up testing and is not included in the present study. EO and BI treatment conditions targeted language areas that have been known to be difficult for school-age children with PLI including vocabulary, grammar, and listening comprehension. The EO condition received treatment solely in English, while the BI condition received treatment primarily in Spanish, with English modelling to make connections between languages. NCP treatment targeted attention and processing speed using nonlinguistic stimuli (e.g. shapes, colours, tones) (see Ebert et al. 2014 for specific treatment procedures).

Assessment measures

Dependent variables were derived from a battery of conventional and experimental measures administered to each child at three times: before and after treatment (pre- and post-testing) and 3 months following treatment (follow-up). Testing was completed by speech–language pathologists or speech–language pathology students who were fluent in the target language (Spanish or English). Treatment and testing were conducted by separate researchers to prevent clinician bias.

At each testing time, participants completed English and Spanish versions of four language tests: Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOW; Brownell 2000a, 2001a), Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROW; Brownell 2000b, 2001b), the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, 4th edition (CELF: Semel et al. 2003; Wiig et al. 2006), and nonword repetition tasks (NWR; Dollaghan and Campbell 1998; Ebert et al. 2008). Dependent measures were standard scores for EOW, ROW and the Core Language score of the CELF, which is a composite score based on four subtests that measure receptive and expressive language skills. Dependent measures for non-word repetition tasks were percent phonemes correct (PCC; Dollaghan and Campbell 1998) for the most dif-ficult level in each language (i.e. four syllables in length for English and five syllables for Spanish).

In addition to the eight language tasks, participants completed three NCP tasks: choice visual detection (CVD; Kohnert and Windsor 2004), auditory serial memory (ASM), and sustained selective attention (SSA). CVD was a measure of processing speed in the visual domain. Participants were shown either a red or blue circle on a computer screen and asked to press one button if the circle was red and another button if the circle was blue. The dependent measure was the average response time (RT) between the onset of the picture and the participant’s button press in milliseconds. ASM was a measure of working memory for nonverbal auditory information (i.e. tones). Participants were asked to determine if two sets of tones were the same or different. Tone sequences increased in length and difficulty from two to five tones per sequence. Participants received a score from 0 to 4 based on the highest level of difficulty in which they reached a criterion of 75% accuracy. Finally, SSA measured selective attention, namely the ability to detect a target sound (i.e. keys rattling) from on ongoing stream of environmental noises. The dependent measure was d’, a signal detection measure that captures both ‘hit rate’ (proportion of target sounds correctly detected) and ‘false alarm rate’ (proportion of non-target sounds incorrectly detected).

Study attrition

All participants completed pre- and post-treatment testing. The attrition rate between post-testing and follow-up was three of 17 children (18%) for the EO condition; four of 16 children (25%) for the NCP condition, and nine of 15 children (60%) for the BI condition. To assess attrition in each condition, we conducted separate Wilcoxon rank sum tests to identify group differences between children who completed all three testing times versus children who did not, using pre-testing scores for language measures (EOW, ROW, CELF, NWR in Spanish and English) and nonlinguistic tasks (CVD, ASM, SSA). For the EO condition, the single group difference was on Spanish EOW (p = 0.04) and was related to lack of variability: the three participants who did not complete follow-up testing scored at floor levels at pre-testing (i.e. SS = 55, < 1%ile). For the NCP condition, there were two group differences on Spanish EOW and ROW. The group difference on Span-ish EOW (p = 0.04) was related to lack of variability (i.e. floor level performance) among the four participants who did not complete follow-up testing. The group difference on Spanish ROW (p = 0.03) indicated that the group of participants who completed follow-up testing scored higher at pre-testing than the four participants who did not (mean of 79 versus 62, respectively). For the BI condition, there were no group differences on any measure. Results from attrition analyses indicated that participants who completed follow-up testing were representative of the full sample in each treatment condition. All missing data were accounted for using maximum likelihood estimation (Long 2012).

Data analysis

Data analysis was based on HLM, conducted using the lmer() function in the lme4 package (Bates 2005) of the R software programme. The time variable was based on the original treatment design for a maximum of three time points: pre-testing, post-testing and follow-up. Time was centred on pre-testing for the intercept to represent language performance prior to treatment. In a preliminary analysis, linear and nonlinear models were compared using procedures outlined in Long (2012). Results indicated comparable AICc weights and median effect sizes between linear and the best nonlinear models. Therefore, linear models were selected to parsimoniously represent the shape of change.

The main analysis consisted of 11 HLMs for each dependent measure: CVD, ASM, SSA, and EOW, ROW, CELF, NWR in each language. Models allowed for potentially different fixed intercepts and slopes across treatment conditions, EO, BI, and NCP, and potential interactions between treatment condition and time. Chronological age at pre-testing served as a covariate (i.e. Age1) to account for the wide range of initial ages. All models included two random effects to account for individual variation in random intercepts and slopes (cf. Long 2012). The following is an example of the HLM for English EOW in R script:

The example HLM consists of time centred on pre-testing (Time0), age at pre-testing as the covariate (AGE1), EO as the reference condition (EOref), and random effects in parentheses (1+Time0|ID). Separate models were conducted using EO, BI, or NCP as the reference condition in order to examine treatment condition as a three-way factor. Treatment conditions were compared using six pair-wise linear contrasts for each dependent variable, namely three linear contrasts for fixed intercepts (i.e. EO versus NCP; BI versus NCP; BI versus EO) and three linear contrasts for fixed slopes (cf. Long 2012).

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for Spanish, En-glish, and cognitive measures by treatment condition and time of testing. Follow-up scores were either better or the same as pre-testing scores, suggesting either improvement or maintenance following treatment. Average standard scores (ROW, EOW, CELF in each language) and average accuracy scores (NWR, ASM, SSA) at follow-up were the same or higher than pre-testing; similarly, average RTs at follow-up were either lower (faster) or the same as pre-testing across conditions.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Time | EO | BI | NCP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | |

| Spanish language measures | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| ROW | 70 (15) | 69 (12) | 73 (16) | 69 (18) | 72 (14) | 71 (15) | 74 (11) | 72 (16) | 73 (13) |

| EOW | 69 (20) | 73 (21) | 72 (19) | 61 (8) | 66 (14) | 63 (10) | 67 (16) | 68 (13) | 68 (15) |

| CELF | 65 (13) | 67 (14) | 68 (15) | 60 (9) | 62 (10) | 61 (16) | 60 (12) | 60 (13) | 60 (15) |

| NWR | 64 (26) | 68 (17) | 75 (16) | 78 (11) | 74 (11) | 75 (12) | 63 (25) | 75 (18) | 71 (14) |

|

| |||||||||

| English language measures | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| ROW | 73 (5) | 76 (8) | 82 (12) | 78 (9) | 82 (7) | 86 (11) | 76 (5) | 78 (7) | 78 (6) |

| EOW | 61 (7) | 68 (9) | 68 (8) | 69 (8) | 72 (8) | 72 (7) | 65 (6) | 67 (9) | 69 (14) |

| CELF | 48 (9) | 55 (12) | 55 (12) | 53 (8) | 59 (9) | 59 (10) | 50 (10) | 54 (13) | 50 (13) |

| NWR | 53 (16) | 56 (15) | 55 (14) | 58 (7) | 65 (11) | 65 (10) | 53 (17) | 54 (15) | 59 (12) |

|

| |||||||||

| Nonlinguistic cognitive measures | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CVD | 857 (148) | 755 (127) | 746 (133) | 684 (134) | 744 (138) | 706 (135) | 709 (79) | 646 (76) | 689 (132) |

| ASM | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.5) |

| SSA | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.8) | 3.7 (1.0) | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.8) |

Notes: Means and standard deviations (SDs) are displayed in parentheses.

ROW = Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test standard scores; EOW = Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test standard scores; CELF = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, 4th edition, standard scores; NWR = Nonword repetition; CVD = Choice Visual Detection; ASM = Audio Serial Memory; SSA = Selective Sustained Attention.

Table 2 displays estimates for fixed intercepts and slopes based on HLMs and followed by linear contrasts between treatment conditions. There were unequal starting points (i.e. fixed intercepts) between participants on two dependent measures: English ROW and CVD. For English ROW, participants in the EO condition had a lower intercept estimate than those assigned to the BI condition (66 versus 71; p = 0.05, 95% CI [−8.9, −0.03]). For CVD, the EO condition had a slower fixed intercept estimate (1135 ms) than both the BI condition (1030 ms; p = 0.01; 95% CI [23.9, 187.2]) and NCP conditions (1013 ms; p = 0.002; 95% CI [44.6, 200.4]). Poorer initial performance by the EO condition on the CVD may have reflected the slightly younger average age as compared to the other two treatment conditions. The average age of participants in the EO condition at pre-testing was 7:10, while average ages of participants in the BI and NCP conditions at pre-testing were 9:0 and 8:7, respectively. Although differences in initial ages between treatment conditions did not reach statistical significance (Ebert et al. 2014), they may have contributed to differences in fixed intercept estimates for CVD, a measure of processing speed, which has been found to be highly dependent on age (Kohnert and Windsor 2004).

Table 2.

Fixed effects estimates

| Intercepts | Slopes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| EO | BI | NCP | Contrasts | EO | BI | NCP | Contrasts | |

| Spanish language measures | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| ROW | 84* (11) | 87* (13) | 89* (12) | EO = BI = NCP | 1.8 (2.1) | 0.8 (2.3) | −0.3 (2.2) | EO = BI = NCP |

| EOW | 99* (12) | 97* (14) | 99* (13) | EO = BI = NCP | 1.0 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.7) | 0.4 (1.7) | EO = BI = NCP |

| CELF | 59* (10) | 54* (12) | 53* (11) | EO = BI = NCP | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.1) | −0.4 (0.9) | EO = BI = NCP |

| NWR | 41* (12) | 52* (14) | 41* (13) | EO = BI = NCP | 5.9* (2.7) | −1.8 (3.3) | 5.5 (2.9) | EO = BI = NCP |

|

| ||||||||

| English language measures | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| ROW | 66* (5) | 71* (6) | 69* (6) | EO < BI; EO = NCP; BI = NCP | 4.1* (1.1) | 3.3* (1.4) | 0.9 (1.2) | EO = BI; BI = NCP; EO > NCP |

| EOW | 53* (7) | 58* (8) | 55* (7) | EO = BI = NCP | 3.5* (0.9) | 3.5* (1.2) | 1.9 (1.0) | EO = BI = NCP |

| CELF | 23* (7) | 23* (8) | 22* (8) | EO = BI = NCP | 3.9* (1.0) | 4.8* (1.3) | −0.001 (1.1) | EO = BI > NCP |

| NWR | 38* (10) | 41* (11) | 35* (10) | EO = BI = NCP | 1.8 (2.1) | 5.3* (2.7) | 3.9 (2.3) | EO = BI = NCP |

|

| ||||||||

| Nonlinguistic cognitive measures | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| CVD | 1135* (84) | 1030* (96) | 1013* (92) | EO > BI = NCP | −61.0* (18.0) | 29.8 (22.6) | −14.9 (19.0) | EO > BI; EO = NCP; NCP = BI |

| ASM | 0.5 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.4) | EO = BI = NCP | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | EO = BI = NCP |

| SSA | 2.0* (0.7) | 2.4* (0.8) | 2.4* (0.7) | EO = BI = NCP | 0.4* (0.1) | 0.5* (0.2) | 0.3* (0.1) | EO = BI = NCP |

Notes: Standard errors are displayed in parentheses.

EO = English only treatment condition; BI = Bilingual treatment; NCP = Nonlinguistic Cognitive Processing treatment. ROW = Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test standard scores; EOW = Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test standard scores; CELF = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals; NWR = Nonword repetition; CVD = Choice Visual Detection; ASM = Audio Serial Memory; SSA = Selective Sustained Attention.

p < 0.05 or a z-score > ±1.96.

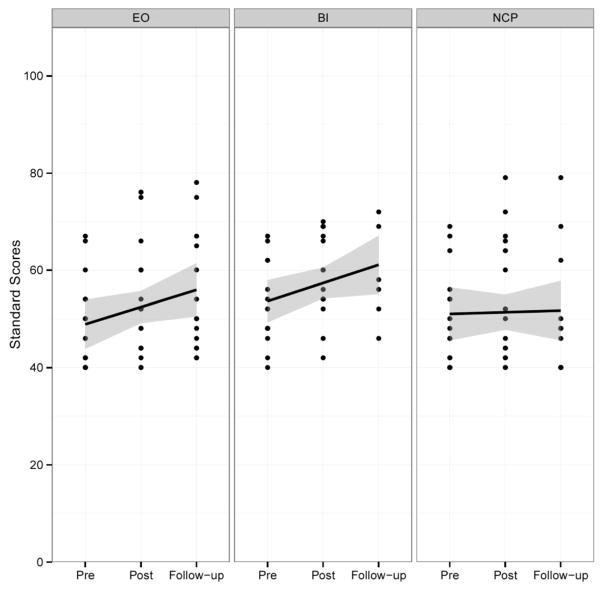

The primary focus of the analysis was on estimates of fixed slopes, namely rates of change over time. As shown in table 2, fixed slope estimates showed different outcomes between Spanish, English, and cognitive measures. Fixed slope estimates for all Spanish language measures were not significantly different from zero. Findings indicated no change in Spanish receptive and expressive vocabulary and overall language proficiency, as measured by ROW, EOW, and CELF, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates performance on Spanish CELF across treatment conditions. The single exception to the find-ing of no change for Spanish was with NWR. The EO condition showed positive change for NWR at a rate of +5.9%/testing time. However, linear contrasts indicated no differences between EO, BI, and NCP conditions, suggesting that the positive change in the EO condition was modest at best.

Figure 1.

Group-level growth trajectories for Spanish CELF across the three conditions of English only (EO), bilingual (BI) and nonlinguistic cognitive processing (NCP). The standard error is shaded in grey. Data points represent individual performance at each testing time: prior to treatment (pre), immediately following treatment (post) and 3 months following the completion of treatment (follow-up).

In contrast to the minimal change in Spanish, there were significant positive changes in English. As shown in table 2, positive change rates were found for EO and BI conditions on English ROW, EOW, and CELF at +3 to 4 standard score points/testing time. Figure 2 illustrates change rates for English CELF across conditions. Additionally, the BI condition showed significant positive change for English NWR with an increase of +5%/time. Although positive change rates were found for the two linguistic conditions (EO and BI), no change was found on any English measure in the NCP condition. For English ROW, the EO condition had a greater slope (+4 standard scores/time) than the NCP condition (+1 standard score/time; p = 0.05; 95% CI [0.1, 6.4]). For English CELF, the EO and BI conditions had greater slopes (about +4 standard scores/time) than the NCP condition (0 standard scores/time) with significant linear contrasts between EO and NCP conditions (p = 0.008; 95% CI [1.0, 6.7]) and between BI and NCP conditions (p = 0.005; 95% CI [1.4, 8.1]).

Figure 2.

Group-level growth trajectories for English CELF across the three conditions of English only (EO), bilingual (BI) and nonlinguistic cognitive processing (NCP). Standard error is shaded in grey. Data points represent individual performance at each testing time: prior to treatment (pre), immediately following treatment (post) and 3 months following the completion of treatment (follow-up).

In addition to positive change in English, results showed positive change for 2 of three cognitive processing tasks (CVD and SSA) in at least one condition. As shown in table 2, the EO condition showed a faster rate of change on CVD (−61 ms/testing time) than the BI condition (+30 ms/time, p = 0.002, 95%CI [−147.4, −34.2]) and the NCP condition that approached sig-nificance (p = 0.07). It should be noted that the intercept for the EO condition was initially higher (i.e. slower RT) than the other two conditions, which may be related to the faster slope. Slopes for BI and NCP conditions were not statistically different from zero. All treatment conditions showed positive growth rates on the SSA with positive rates of change ranging from +0.3 to 0.5 d’units/time. There was no change in ASM in any treatment condition.

In sum, HLM analysis suggested positive change in English on all measures, positive change in cognitive skills primarily in the area of sustained attention, and no change in Spanish. Differences in rates of change between EO, BI, and NCP conditions were minimal, though the two language treatment conditions (EO and BI) outperformed the NCP condition in English.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine longer-term treatment effects on language and cognitive skills for school-age Spanish–English BI children with PLI. Children participated in one of three treatment conditions focusing on skills in EO, Spanish and English BI or NCP. Effects immediately following treatment are reported in Ebert et al. (2014). The present study uses hierarchical linear modelling to calculate rates of change in Spanish, English, and cognitive processing 3 months following treatment and to compare longer-term effects across treatment conditions.

It is important to frame the following discussion of results within the specific features of the analysis. Data analysis is based on a highly conservative estimate of change over time. First, we focus on generalization of skills rather than performance on items directly targeted in treatment. For example, gains in vocabulary are measured using norm-referenced vocabulary tests rather than the specific vocabulary words targeted during treatment. Second, longitudinal trajectories are based on standard scores instead of raw scores for consistency across language outcomes. Our participants spanned a wide age range (5–11 years), and multiple standardized tests were used to measure expressive and receptive vocabulary (EOW, ROW) and overall abilities (CELF) in each language. Criteria to begin and end testing varied for each test as a function of chronological age and language of administration, which made longitudinal trajectories using raw scores difficult to interpret. It is important to note that trajectories based on standard scores that show no change over time (i.e. zero growth) may actually reflect positive change in raw scores and growth that is on par with same-aged peers.

The present study has three main findings. First, we found positive change on all English language measures, at least for EO and BI conditions. Rates of change on English standardized tests ranged from 3.3 to 4.8 standard score points/testing time. Positive rates of change of 3 standard scores or greater are substantial compared to the few previous studies of longer-term treatment effects with school-age children. Gillam, et al. (2008) reported an average increase of 2 standard score points per follow-up testing time, at three and six months post treatment. Boyle et al. (2009) reported increases ranging from 0 to 5 points at 12 months following treatment. Positive development in English underscores the capacity for children with moderate to severe language impairment to learn language in face of a compromised language system even beyond the time of direct treatment. As expected, EO treatment promotes English language skills, particularly related to vocabulary, grammar, and listening comprehension. The vast majority of speech–language pathologists in the US and the UK are capable of providing direct language treatment only in English. The American Speech–Language–Hearing Association reported that only 5% of over 150 000 members have native or near-native proficiency in a second language (ASHA 2012); in the UK, Stow and Dodd (2003) estimate that fewer than 1% of clinical professionals may be considered ‘specialists in bilingualism’.

Study results provide some empirical support for the conventional practice (albeit not best practice) of EO language treatment. However, there are at least two caveats. First, results showed that treatment in EO did not promote gains in Spanish. This lack of spontaneous transfer of skills from English to Spanish is consistent with previous work suggesting that children with language impairment have difficulty generalizing skills (Hsu and Bishop 2011). A clinical implication is to support explicit, systematic connections between English and Spanish to support transfer of skills between the two languages (Kohnert 2013). Second, it should be noted that treatment was provided in a dosage much more intensive than typical school-based services (300 min/week versus 60 min/week). Further study is needed to examine treatment dosage, specifically the frequency and amount of treatment required to cause longer-term change in English language outcomes among bilingual children.

Finally, it is important to note that the BI condition showed the same English language improvement as the EO condition. Participants in the EO condition received treatment solely in English, while participants in the BI condition received treatment primarily in Spanish with explicit connections between Span-ish and English. This finding is consistent with the mounting empirical evidence with typically developing bilingual learners showing that bilingual school programmes achieve comparable English outcomes to EO programmes (for a meta-analysis, see Rolstad et al. 2005). Study results extend the literature to bilingual children with PLI and support the notion that instruction that incorporates two languages does not detract from English language development.

The second main finding was maintenance of Spanish language skills, 3 months following the completion of treatment. In the social context of minority language learning, no change in L1 skills (versus attrition) is noteworthy, particularly when the metric for change is standard scores. Similar to Gujarati or Punjabi in the UK, Spanish has a minority status in the United States with less prestige than English; children who speak Spanish as a minority L1 have more limited opportunities to listen and practice the language in school and the larger community. Although the BI condition was conducted primarily in Spanish, treatment was conducted within a broader social context in which English was the dominant language of the school and community. Bilingual treatment provided within a relatively short time period may not have been enough to promote positive change in Spanish. The risk of L1 attrition is present even for typical bilingual learners particularly when there is a lack of L1 support in the school or community (Jia and Aaronson 2003). Bilingual children with PLI have weakened child-internal resources for learning language (Kohnert 2013) and may be at a greater risk for L1 attrition than their typical bilingual peers (Salameh et al. 2004). Therefore, although bilingual children with PLI in the present study did not show positive change in Spanish, the lack of negative change suggests that intensive language treatment may potentially stave off L1 attrition. Future studies that include a longitudinal comparison between bilingual children with PLI who did and did not receive treatment are needed to examine whether treatment in the L1 directly contributed to longer-term maintenance of L1 skills.

Finally, although participants in the BI condition showed greater gains in Spanish than participants in the EO condition immediately following treatment (Ebert et al. 2014), the present study did not find differences in Spanish change rates between EO and BI conditions. It is unclear why the present study did not find relatively greater longitudinal outcomes for Spanish in the BI condition. The finding is inconclusive at this point and may be related to methodological limitations. The BI condition had fewer participants who completed follow-up testing (60% attrition). It is noted that the BI condition showed positive change rates in English—on par with the EO condition—demonstrating that detecting overall change in the BI condition was methodologically possible. However, the large attrition in the BI condition may have limited the ability to make between-condition comparisons on differential treatment outcomes. Based on the evidence available, current best practice for clinical action continues to be systematic support for all the languages a child needs to be successful in home, school, and community settings (Kohnert 2013). Further investigation is needed to examine treatment effects that support the L1 alongside L2 gains, particularly when the clinician does not speak the minority L1 (Pham et al. 2011).

The third main finding was in the area of cognitive processing. All conditions increased on a measure of sustained selective attention. Only one condition (the EO condition) made gains on our measure of nonlin-guistic processing speed, and there were no longer-term gains on the working memory measure. For the condition that received NCP treatment, which was designed to improve speed of processing and sustained selective attention, continued gains were seen in one of the two areas targeted directly by treatment. However, the hypothesis that direct treatment of these basic nonlinguis-tic cognitive skills would result in superior gains was not supported: gains made by the NCP condition on cognitive measures were equivalent to or smaller than gains made by the language-based conditions on these skills.

This result may stem in part from the complexity of altering basic cognitive skills through behavioural treatment (Rabipour and Raz 2012). Alternatively, the relatively comparable gains made by the two language-based treatment groups may point to the relative success of language treatment in modifying these skills, particularly attention. Our findings are consistent with previous work suggesting that intensive language treatment for children with PLI may operate, in part, by improving general attention skills (Gillam et al. 2008, Stevens et al. 2008). In other words, scaffolded experience with language forms and meanings may effectively engage and thus improve general cognitive processing skills. The current findings supplement prior literature in this area by finding similar gains across multiple treatment conditions on a behavioural measure of attention. However, our study design did not allow us to rule out general maturation as an alternative explanation for the attention gains seen here. Future studies that control for general maturation (e.g. through inclusion of a no-treatment condition) are needed to further explore this possibility.

Finally, the NCP condition showed no significant change in Spanish and English language measures over time. Because there was no longer-term improvement on most nonlinguistic processing skills, we did not anticipate transfer of skills from the cognitive domain to the language domain. Ultimately, our results do not negate the importance of cognitive processing skills for ongoing language learning in children with PLI, but rather suggest that these skills may be best supported in tandem with focused language practice.

Future directions

While the present study provides foundational evidence for the longer-term effects of treatment for bilingual children with PLI, a number of questions remain to be answered. First, it is clear that the social context of language learning influences language growth for school-aged children who speak a minority home language. Our work examined children who speak Spanish as their L1, within the social context of the United States. It is possible that children in other countries, who speak another L1 but are also affected by PLI, may demonstrate slightly different responses to treatment. International and cross-linguistic investigations of treatment for bilingual children with PLI are warranted to expand this fledgling literature.

In addition, while our conclusions about the longer-term effects of NCP treatment are largely neutral, the concept of treatment on cognitive processing skills which provide a foundation for longer-term improvements in language learning for children with PLI remains worthy of exploration. Modest gains in the NCP condition and comparable gains in sustained attention across treatment conditions suggest that it is easier to take language out of cognitive processing than to take cognitive processing out of language (see Ebert et al. 2014 for a discussion). Future studies are needed to systemically embed cognitive processing skills into focused language practice. Ongoing consideration of the factors that underlie PLI and effective means of modifying them may lead to treatment approaches with greater longer-term effects.

What this paper adds?

What is already known on the subject?

Computer-based and interactive behavioural interventions have been found to be generally effective for monolingual school-age children with PLI. However, little is known about the maintenance of treatment effects following the discontinuation of services. For bilingual children there are few previous studies investigating differential effects across treatment approaches, and no studies have examined maintenance effects.

What this study adds?

This study assessed bilingual children with PLI 3 months after completing an intervention programme to determine whether treatment gains were maintained, diminished or augmented in the post-treatment period. Using hierarchical linear modelling, we found continued growth on English language measures for children who received one of two language-based conditions – English only (EO) and bilingual Spanish–English maintenance in Spanish (BI) – and modest gains in nonlinguistic cognitive processing (NCP). Findings support (1) the integration of NCP targets in language intervention with school-age children; and (2) the need for systematic support of the two languages of bilingual children with PLI.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD R21DC010868) awarded to Kathryn Kohnert; and by an NIDCD R21 Postdoctoral Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research awarded to Giang Pham. The authors are very grateful for the collaboration of Dr Frank Cirrin and the faculty, staff and administrators in the Minneapolis Public Schools. They thank project coordinators Jill Rentmeester Disher and Bita Payesteh as well as research assistants in the Center for Cognitive and Social Processes, University of Minnesota, who assisted with data collection, coding and scoring. Finally, they thank the participants and their families. Declaration of interest: The authors report no con-flicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- ASHA. [accessed on 11 October 2013];Demographic Profile of ASHA Members Providing Bilingual Services. 2012 (available at: http://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/Demographic-Profile-Bilingual-Spanish-Service-Members.pdf)

- Bates D. Fitting linear mixed models in R. R News. 2005;5:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle JM, McCartney E, O’Hare A, Forbes J. Direct versus indirect and individual versus group modes of language therapy for children with primary language impairment: principal outcomes from a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2009;44:826–846. doi: 10.1080/13682820802371848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publ; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publ; 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—Spanish-Bilingual Edition. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publ; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—Spanish-Bilingual Edition. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publ; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan C, Campbell T. Nonword repetition and child language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1136–1146. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4105.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbels SH, van der Lely HK, Dockrell JE. Intervention for verb argument structure in children with persistent SLI: a randomized control trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:1330–1349. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/093). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K, Kalanek J, Cordero K, Kohnert K. Spanish nonword repetition: stimuli development and preliminary results. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2008;29:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K, Kohnert K, Pham G, Rentmeester Disher J, Payesteh B. Three treatments for bilingual children with primary language impairment: examining cross-linguistic and cross-domain effects. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014;57:172–186. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0388). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, Loeb DF, Hoffman LM, Bohman T, Cham-plin C, Thibodeau L, Widen J, Brandel J, Friel-Patti S. The efficacy of Fast For Word language intervention in school-age children with language impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2008;51:97–119. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HJ, Bishop DVM. Grammatical difficulties in children with specific language impairment: is learning deficient? Human Development. 2011;53:264–277. doi: 10.1159/000321289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Aaronson D. A longitudinal study of Chinese children and adolescents learning English in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24:131–161. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CJ, Beitchman JH, Young A, Escobar M, Atkinson L, Wilson B, Brownlie EB, DOUGLAS L, Taback N, LAM I, Wang M. Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: speech/language stability and outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:744–760. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4203.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K. Language Disorders in Bilingual Children and Adults. 2. San Diego, CA: Plural; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Windsor J. The search for common ground part II: nonlinguistic performance by linguistically diverse learners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:891–903. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/066). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J, Tomblin JB, Zhang X. Characterizing the growth trajectories of language-impaired children between 7 and 11 years of age. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2008;51:739–749. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/052). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Weismer S, Miller C, Francis D, Tomblin JB, Kail R. Speed of processing, working memory, and language impairment in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:408–428. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/029). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. Longitudinal Data Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences Using R. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis J, Emmerzael K, Sorenson Duncan T. Assessment of English language learners: using parent report on first language development. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2010;43:474–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham G, Kohnert K. A longitudinal study of lexical development in children learning Vietnamese and English. Child Development. 2014;85:767–782. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham G, Kohnert K, Mann D. Addressing clinician–client mismatch: language intervention with a bilingual Vietnamese–English preschooler. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2011;42:408–422. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0073). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabipour S, Raz A. Training the brain: fact and fad in cognitive and behavioral remediation. Brain and Cognition. 2012;79:159–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Hoffman L, Wexler K. Judgments of omitted BE and DO in questions as extended finiteness clinical markers of SLI to fifteen years: a study of growth and asymptote. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:1417–1433. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0171). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolstad K, Mahoney K, Glass GV. The big picture: a meta-analysis of program effectiveness research on English language learners. Educational Policy. 2005;19:572–594. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh E, Hakansson G, Nettelbladt U. Developmental perspectives on bilingual Swedish–Arabic children with and without language impairment: a longitudinal study. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2004;39:65–91. doi: 10.1080/13682820310001595628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semel E, Wiig EH, Secord WA. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals. 4. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C, Fanning J, Coch D, Sanders L, Neville H. Neural mechanisms of selective auditory attention are enhanced by computerized training: electrophysiological evidence from language-impaired and typically developing children. Brain Research. 2008;1205:55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stow C, Dodd B. Providing an equitable service to bilingual children in the UK: a review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2003;38:351–377. doi: 10.1080/1368282031000156888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiig EH, Secord WA, Semel E. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Spanish 4th Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]