Abstract

Purpose

To describe and compare the frequency and type of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) reported by men and women at the time they were recruited from urology and urogynecology clinics into the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) multi-center, prospective, observational cohort study.

Materials and Methods

Six research sites enrolled treatment-seeking men and women who reported any LUTS at a frequency more than “rarely” during the past month on the LUTS tool. At baseline, study participants underwent a standardized clinical evaluation and completed validated questionnaires; urological tests were performed, including pelvic/rectal examination, post-void residual, and urinalysis.

Results

A total of 545 women and 519 men were enrolled. The mean age was 58.8 ± 14.1 years. At baseline, nocturia, frequency, and a sensation of incomplete emptying were similar between men and women, whereas men experienced more voiding symptoms (90% vs. 85%, p=0.007), and women reported more urgency (85% vs. 66%, p<0.001). Women also reported more urinary incontinence (any type) than men (82% vs. 51% p<0.001), which was predominantly mixed incontinence (57%). Men rarely reported stress incontinence (1%), but did have other urinary incontinence (44% post-void dribbling) or urgency incontinence (46%). Older participants had higher odds of reporting symptoms of nocturia and urgency.

Conclusion

In this large treatment-seeking cohort of men and women, LUTS varied widely by sex and age. Men reported more voiding symptoms and non-stress or urgency urinary incontinence, whereas women reported more incontinence overall and urgency. Older participants had greater odds of urgency and nocturia.

Keywords: lower urinary tract symptoms, nocturia, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence

INTRODUCTION

The term “lower urinary tract symptoms” (LUTS) includes a wide range of urinary symptoms, including urgency, frequency, dysuria, nocturia, post-void dribbling, and urinary incontinence (UI). Population prevalence and incidence of LUTS varies depending on sex, age, ethnicity, and many other factors. For example, in the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, a community-based prospective cohort study, one in ten adults developed LUTS at 5-year follow-up, and symptoms were significantly more prevalent in women and non-white minorities,1 with a sharp increase with advancing age. Primarily due to an aging US population, Ganz et al estimated that, in 2020, total national costs of overactive bladder symptoms alone will exceed $82 billion annually.2 Importantly, LUTS also adversely affect mental and physical quality of life.3–5 There is a large knowledge gap in the understanding of the pathophysiology behind LUTS; therefore, treatments are often inadequate.6

The Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) (www.nih-lurn.org) was established to better characterize the type, frequency, distribution, and patients’ experiences with LUTS, with four objectives of: 1) identifying and explaining the important subtypes of LUTS in a treatment-seeking cohort; 2) creating more specific and sensitive validated measuring tools of patient experiences of LUTS; 3) disseminating novel findings to researchers, clinicians, and patients; and 4) generating data, research tools, and biological samples for future studies.7 None of the previously published longitudinal studies of LUTS have included both men and women who were care-seeking. A care-seeking population is expected to be distinct from population studies and uniquely important since these patients are significantly bothered by their symptoms. The types and distribution of symptoms that drive persons to seek care may be distinct from those experienced by persons in the community at large. The primary purpose of this specific report of the baseline symptoms and methodology of LURN was to describe the LUTS of a cohort of treatment-seeking men and women; secondary aims were to compare the reported LUTS between males and females, as well as how they differ by age.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Boards from all participating sites approved the study protocol for the LURN Observational Cohort Study. LURN is a multi-center National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH/NIDDK)-sponsored research network consisting of six US research sites and a data coordinating center (DCC). The LURN also includes an External Expert Panel that provides oversight for all LURN protocols. This treatment-seeking cohort of both men and women was recruited from January 2015 through January 2017 from patients who presented for care at tertiary referral centers for LUTS. All participants were at least 18 years old and were primarily those presenting for the first time for treatment of LUTS to a LURN physician in urology or urogynecology clinics. In order to accelerate recruitment, the study protocol was modified to permit recruitment of men returning to the clinic for treatment of LUTS (not first presenters). Patients were invited to participate if they reported at least one urinary symptom based on a 1-month recall period on the LUTS Tool.8 Table 1 lists the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, and all participants were provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the LURN observational cohort study.

Inclusion criteria:

|

Deferral criteria (once issue investigated or resolved patient eligible):

|

Exclusion criteria:

|

Abbreviations: GU, genitourinary; LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms.

Data collection at the baseline clinic visit included a standard clinical examination, including digital rectal prostate exam in men and pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) and pelvic floor muscle assessment in women, using the Oxford grading system. All participants were screened with a urinalysis and post-void residual with catheterization or ultrasound bladder scan. Participants were instructed to withhold initiating new medical or surgical therapies for LUTS prior to the study visit and specimen collection. During a separate study visit, data collected included patient-reported urinary, pelvic floor, and psychological symptoms. During this research visit, demographic information collected on all participants included date of birth, sex, race, ethnicity, education, employment, and marital status. Participants were queried regarding past medical and surgical history; diet; use of alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine; obstetric history; menopausal status; and use of hormone therapy. For each participant, we calculated their Functional Comorbidity Index from 18 diagnoses.9 We collected family history among first-degree relatives who have been diagnosed and/or treated for LUTS. All current prescription and over-the-counter medications were recorded.

Participants completed a battery of validated survey instruments that assessed urinary and bowel function, generic health, mental health, and other symptoms during the study visit. Table 2 outlines these survey instruments.8,10–21

Table 2.

Survey instruments used in LURN observational cohort.

| Instrument | Domains Assessed | Number of Items | Recall Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUTS Tool8 | Severity and bother of 22 urinary symptoms | 44 | Past week |

| American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI)10 | Severity of 7 urinary symptoms and 1 QOL question | 8 | 4 weeks |

| PROMIS gastrointestinal: constipation subset, diarrhea subset, and bowel incontinence subset21 | Presence and severity of constipation, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence | 9, 5, and 4 | Past week |

| International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)11 | Erectile function in men | 5 | 6 months |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR)12 | Sexual function among women with pelvic organ prolapse or urinary or fecal incontinence | 20 | None |

| Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20)20 | Urinary, prolapse, and colorectal symptom – presence and associated bother | 20 | 3 months |

| Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI)13 | Symptoms associated with chronic pelvic pain in men and women | 9 | 7 days |

| Childhood Traumatic Events Scale14 | Occurrence of childhood traumatic events | 6 | None |

| PROMIS Depression and Anxiety Short Forms15 | Emotional distress, including depressed mood, anxiety, and worry | 16 | 7 days |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)16 | Subjective stress | 10 | 4 weeks |

| PROMIS Sleep Disturbance Short Form17 | Sleep disturbance | 8 | 7 days |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAC-SF)18 | Four graduated levels of activity | 9 | 7 days |

| PROMIS Physical Function, Mobility Subdomain19 | Lower extremity function | 16 | 7 days |

Abbreviations: LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; QOL, quality of life.

Participants also completed a 3-day fluid intake and urinary diary within 4 weeks of the baseline visit and before initiating any prescribed treatment. The diary recorded fluid intake, volume of urine voided, episodes of urinary leakage, and whether leakage occurred with activity or urgency.

Our study was powered based on four basic types of hypothesis tests: t-tests, logistic regression, correlations, and chi-square tests. For the full 1000-person cohort, >90% power was achieved for detecting differences between groups as small as 0.3 standard deviations for urinary symptom ratings (using a t-test), odds ratios (ORs) of 1.3, or proportions of 0.35 versus 0.50 for urinary symptom presence or absence (using logistic regression or chi-square test, respectively) when subgroups were split 50%–50% (e.g., sex). For less prevalent group comparisons, e.g., diabetes or obesity, >90% power was achieved for differences between groups as small as 0.4 standard deviations for symptom ratings, ORs of 1.5, or proportions of 0.30 versus 0.50 for urinary symptom presence or absence when subgroups were split 90%–10%.

Study participants completed follow-up assessments with the instruments outlined in Table 1 at 3 and 12 months after their initial assessment to evaluate the trajectory of their urinary symptoms in the context of the treatments they received. Additional information collected at these time points included an interval clinical history that assessed any changes in medical or surgical therapy from the prescribed plan. The results presented in this study are limited to the baseline assessment.

Blood, saliva, urine, and biologic flora of patients are associated with LUTS, specimens were prospectively collected, processed, and stored at the NIDDK Biorepository for biomarker and other studies. Specific details of biospecimen collection are described within the Supplemental Text.

The primary measures of LUTS for this report are the validated LUTS Tool, with a 1-week recall,8 and the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI). The AUA-SI was initially developed to assess the severity of LUTS associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH),10 but it has been utilized in women.22

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the LURN cohort were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables by sex and overall. Tests for differences by sex were performed using chi-square test and Wilcoxon two-sample tests. Frequency and percentage of participant responses to the LUTS Tool and AUA-SI questions were calculated by sex; overall and percentages of responses to the LUTS Tool severity items were graphed by sex using horizontal stacked bar charts.

UI subtype was determined from responses to questions 16a-g on the LUTS Tool. Participants were classified as having stress UI (SUI) if they answered “sometimes” or more often on at least one of two questions related to experiencing leakage when they exercised, laughed, coughed, or sneezed. Those who responded “sometimes” or more to leakage due to a sudden feeling of needing to rush to urinate were considered to have urgency UI (UUI). Patients were classified as mixed UI (MUI) if they fulfilled criteria for both SUI and UUI. Finally, those indicating leakage during sleep, sex, just after voiding, or for no reason who did not meet criteria for any of the aforementioned groups were classified as having Other UI.

RESULTS

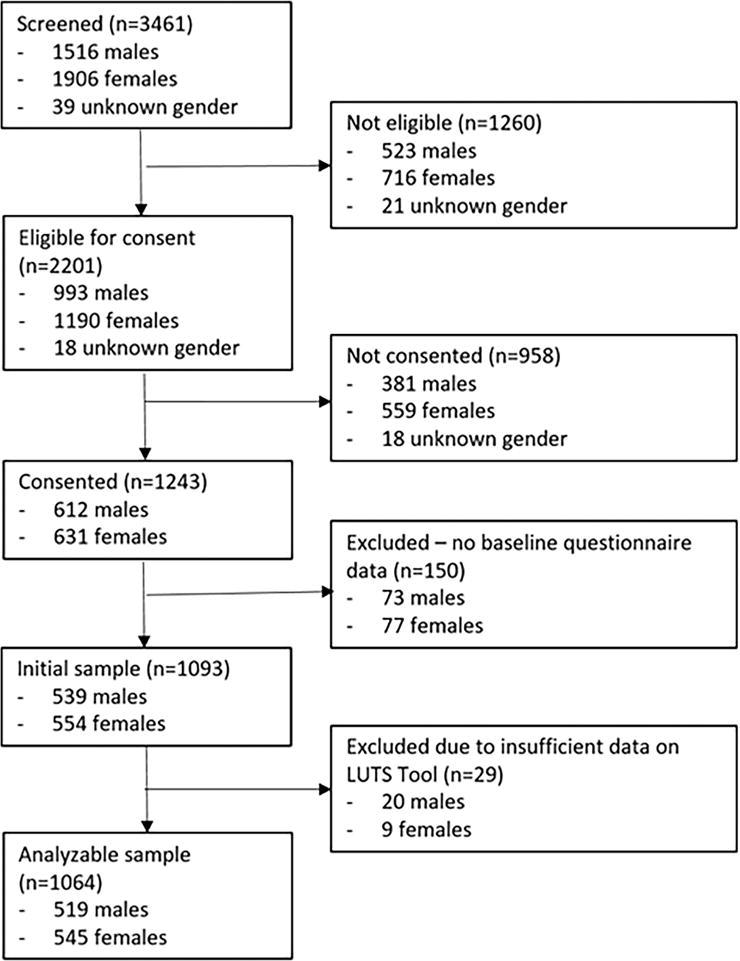

Of 3461 patients screened between January 2015 to January 2017, 2201 were eligible for consent; of these, 1231 consented. (For reasons for ineligibility and refusal of consent, see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.) Of those, 150 participants were excluded because they did not complete the baseline clinical exam, and 29 were excluded due to inadequate symptom reporting on the LUTS Tool. (Less than two-thirds of the form was complete.) The final analytical sample was 1064 participants: 545 women and 519 men (Figure 1). Overall, the mean age of the cohort was 58.8± 14.1 years, and participants were predominantly white (83%). Female participants were significantly younger than the males (mean age 56.4 vs. 61.2, p < 0.001). Median body mass index (BMI) was 28.9 (interquartile range [IQR] 25.1–33.4) kg/m2, with 43% of all participants categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). A history of diabetes and smoking was more common in men (19% and 46%, respectively) compared with women (14% and 35%, respectively, p = 0.073 for diabetes and p < 0.001 for smoking). Only 3% of patients reported currently using antimuscarinic medications for the bladder. Almost a third of women had previously undergone a hysterectomy, and 12% had already undergone a surgical procedure for incontinence or prolapse. Among the men, 4% had undergone prostate surgery for benign conditions in the past, and 39% and 15% reported using alpha blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 1.

STROBE Diagram.

Table 3.

Demographics and medical history of LURN participants by sex.

|

Male (n=519) |

Female (n=545) |

Total (n=1064) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

N% or Mean (SD) |

N% or Mean (SD) |

N% or Mean (SD) |

||

| Age (mean [SD]) | 61.2 (13.3) | 56.4 (14.5) | 58.8 (14.1) | <.001 |

| Race | 0.620 | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 8 (1%) | |

| Asian | 20 (4%) | 14 (3%) | 34 (3%) | |

| African-American | 53 (11%) | 65 (12%) | 118 (11%) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| White | 418 (84%) | 448 (83%) | 866 (83%) | |

| Multi-racial/other | 6 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 11 (1%) | |

| Hispanic | 22 (4%) | 21 (4%) | 43 (4%) | 0.907 |

| BMI kg/m2 (median [IQR]) | 28.6 (25.6–32.6) | 29.3 (24.7–34.7) | 28.9 (25.1–33.4) | 0.448 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 4 (1%) | 12 (2%) | 16 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 105 (20%) | 144 (26%) | 249 (23%) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9 | 204 (39%) | 142 (26%) | 346 (33%) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 206 (40%) | 247 (45%) | 453 (43%) | |

| Current or former smoker | 238 (46%) | 188 (35%) | 426 (40%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes type I or II | 96 (19%) | 78 (14%) | 174 (16%) | 0.073 |

| Number of vaginal births (median [IQR]) | – | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | – | |

| Post-menopausal | – | 347 (65%) | – | |

| Hormone use | – | 62 (18%) | – | |

| Anticholinergic medication use | 18 (3%) | 11 (2%) | 29 (3%) | 0.147 |

| Anti-constipation medication use | 43 (8%) | 34 (6%) | 77 (7%) | 0.198 |

| Alpha blocker medication use | 202 (39%) | 9 (2%) | 211 (20%) | <.001 |

| 5α-reductase medication use | 78 (15%) | – | – | <.001 |

| Previous surgery (multiple possible) | ||||

| Urgency urinary incontinence | 1 (0%) | 6 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 0.067 |

| SUI/prolapse | – | 67 (12%) | – | . |

| Hysterectomy | – | 164 (30%) | – | . |

| Prostate | 23 (4%) | – | – | . |

| Urethral dilation | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 9 (1%) | 0.683 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 0.167 |

| Functional comorbidity index (median [IQR]) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.330 |

| Prolapse stage (n=458)α | ||||

| Stage 0 | – | 143 (31%) | – | |

| Stage 1 | – | 147 (32%) | – | |

| Stage 2 | – | 139 (30%) | – | |

| Stage 3 | – | 28 (6%) | – | |

| Stage 4 | – | 1 (0%) | – | |

| Prostate findings (n=450)α | ||||

| Nodule/anomaly | 8 (2%) | – | – | |

| Normal/enlarged prostate | 442 (98%) | – | – | |

| Urinalysis results | ||||

| Nitrate positiveβ | 4 (1%) | 10 (2%) | 14 (2%) | 0.149 |

| Red blood cell positiveγ | 19 (5%) | 34 (10%) | 53 (7%) | 0.006 |

| White blood cell positiveβ | 17 (4%) | 54 (11%) | 71 (8%) | <.001 |

| Glucose positiveβ | 30 (7%) | 16 (3%) | 46 (5%) | 0.015 |

| Urine specific gravity (median [IQR])β | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | <.001 |

| pH (median [IQR])β | 6.0 (5.0–6.5) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) | 6.0 (5.0–6.5) | <.001 |

| PVR (ml) (median [IQR]) (n=416 male, 464 female)β | 27.0 (0.0–78.5) | 25.0 (10.0–60.0) | 26.0 (6.0–67.0) | 0.254 |

| AUA-SI (median [IQR])α | 13.0 (8.0–18.5) | 12.0 (8.0–16.0) | 12.0 (8.0–17.0) | 0.004 |

| AUA QOL (median [IQR])α | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | <.001 |

P-value for male versus female from chi-square test or Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

Missing 6%–8%

Missing 13%–17%

Missing 32%

Abbreviations: AUA-SI, American Urological Association Symptom Index; BMI, body mass index; LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; PVR, post-void residual; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; SUI, stress urinary incontinence.

A comparison of responses to the LUTS tool by sex demonstrated that a greater number of women experienced more than rare incontinence on a weekly basis than men (67% vs. 49%, Supplemental Table S3 and Supplemental Figure S1). In contrast, men reported more voiding symptoms, including hesitancy (48% vs. 24%), intermittency (53% vs. 25%), straining (28% vs. 19%), and weak stream (61% vs. 29%) compared with women. Responses to AUA-SI questions by sex showed similar patterns to the LUTS Tool (Supplemental Figure S2). The full distribution of participant responses, including both the LUTS Tool and AUA-SI, can be found in Supplemental Table S3.

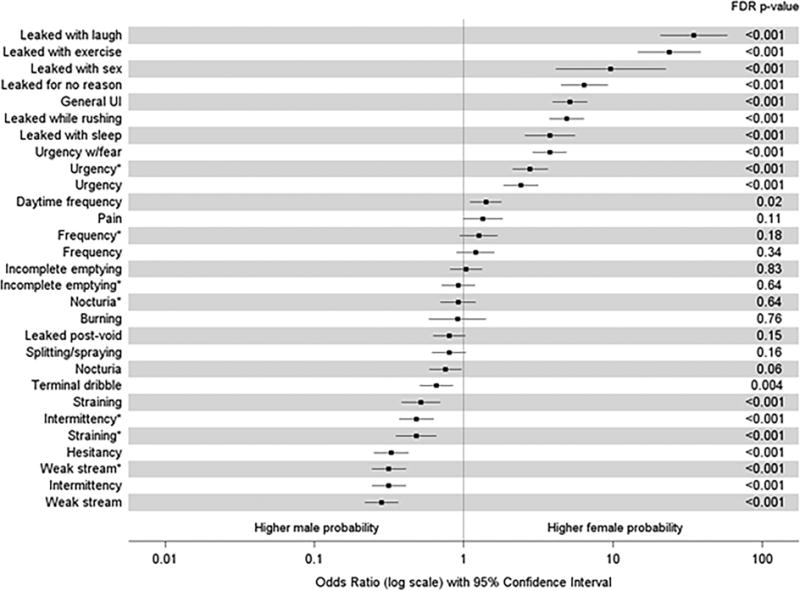

When symptoms were combined into the categories of present (defined as “sometimes”, “often”, or “almost always”) or absent (“never” or “rarely”), after adjusting for age, men were far more likely to report that they have to strain, have their urine stream start and stop, have hesitancy, or a weak stream (age-adjusted OR [95% confidence interval (CI)] comparing females vs. males 0.52 [0.38–0.70], 0.31 [0.24–0.41], 0.33 [0.25–0.43], and 0.28 [0.22–0.36], respectively). Women, in contrast, reported more UI, more fear of urgency and UUI (OR [95% CI] comparing females vs. males 5.13 [3.92–6.72], 3.78 [2.90–4.92], and 4.89 [3.73–6.40], respectively). Urinary frequency was similar between groups, as was nocturia and a sense of incomplete bladder-emptying (Figure 2).

Figure 2. ORs (female vs. male) of LUTS symptoms by sex (adjusted for age).

Results from bivariate logistic regression models, with squares denoting ORs comparing female with male participants on the log-odds scale for each item on the LUTS Tool and AUA (AUA items denoted by *). Lines extend to the lower and upper 95% CIs. P-values listed on the right were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method.

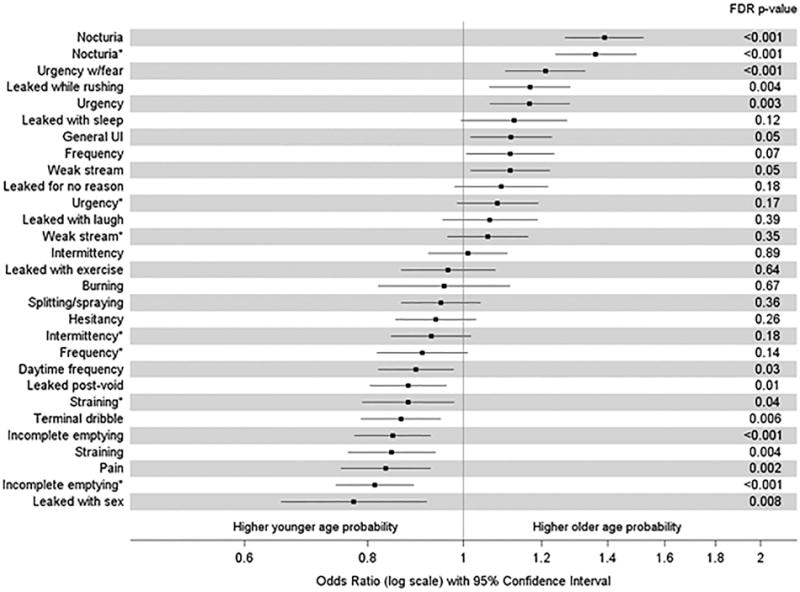

Nocturia was more likely to occur in older patients (sex-adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.39 [1.27–1.52] per 10-year increase in age), as was fear of leakage due to urgency (sex-adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.21 [1.10–1.33] per 10-year increase in age) and UUI (sex-adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.17 [1.06–1.28] per 10-year increase in age). Younger patients had greater odds of leakage with sexual activity, sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, straining, and leaking right after urinating (sex-adjusted OR [95% CI] 0.77 [0.65–0.92], 0.85 [0.77–0.93], 0.85 [0.76–0.94], 0.88 [0.80–0.96] per 10-year increase in age, respectively) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ORs (per 10 year increase in age) of LUTS symptoms by age (adjusted for sex).

Results from bivariate logistic regression models, with squares denoting ORs comparing two participants with a 10-year age difference on the log-odds scale for each item on the LUTS Tool and AUA (AUA items denoted by *). Lines extend to the lower and upper 95% CIs. P-values listed on the right were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method.

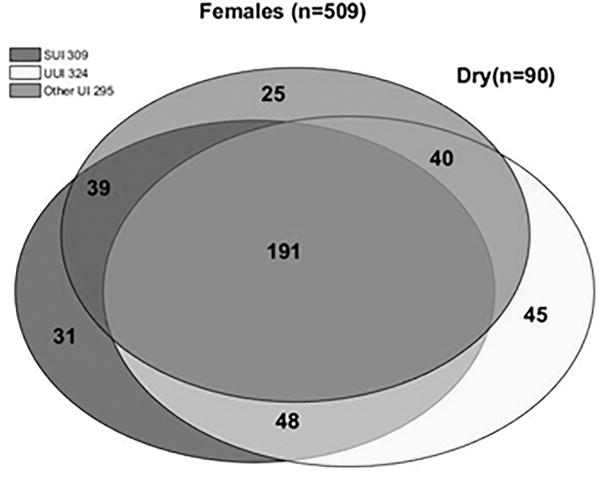

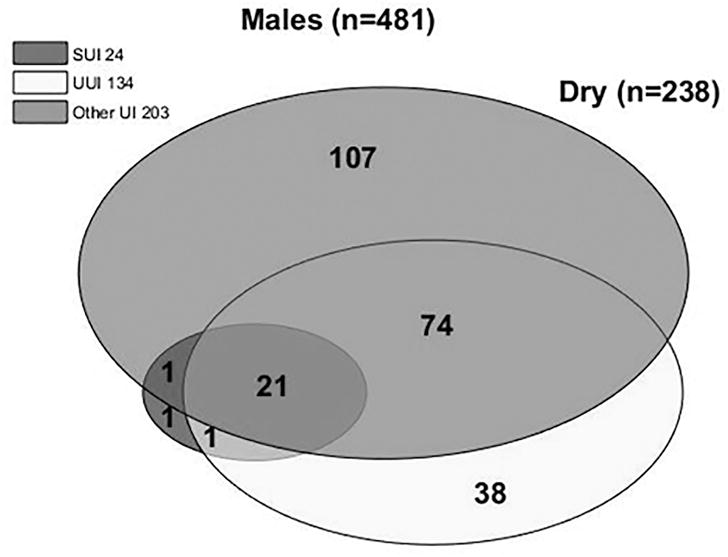

Determination of UI type was completed for men (n=481) and women (n=509) that completed all seven questions related to incontinence on the LUTS Tool (16a-g). Overall, UI combined was more common in women than men (82% vs. 51%). SUI was more common in women, and Other UI was more common in men. The most common type of UI among women with UI was MUI (57%), followed by UUI (20%, Figure 4). Men who leaked, in contrast, most commonly had UUI (46%) and Other UI (44%), with most of the latter being post-void dribbling. SUI or MUI were uncommon in men with UI (n = 2/243 and n = 22/243 respectively).

Figure 4. Venn diagram of incontinence subtypes based on LUTS tool responses.

Each circle represents the total number of participants with a given type of incontinence. Circle areas are proportional to the number of participants with a given type of incontinence relative to the total number of participants with incontinence. Each overlapping section represents the number of people with multiple (2 or 3) types of incontinence. A) Females; B) Males.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that LUTS in treatment-seeking men and women vary not only with sex, but also with age. Overall UI is more prevalent in women, and men report more voiding symptoms.

Sex-specific urinary symptom characteristics have been reported in studies similar to ours.5,23,1 In this cohort, incontinence of any type was more common in women than men, but surprisingly, over half of all men reported some degree of incontinence, which mainly comprised post-void dribbling, but also UUI. Women more commonly reported SUI, which is not surprising, given that 20% of women will have surgery for SUI or pelvic organ prolapse in their lifetime.24 Our results that women more often report UI is qualitatively similar to findings of the BACH Survey, a community-based study of racially diverse men and women, where 10.4% of women and only 5.3% of men reported urinary leakage.1 Not surprisingly, the overall prevalence of incontinence was lower in the BACH Survey compared with our cohort, since it enrolled persons living in the community rather than tertiary care treatment-seeking patients.

Several urinary symptoms affected men and women similarly. Urinary frequency, nocturia, and a sense of incomplete bladder emptying were common in both sexes, challenging the common misconception that women experience more LUTS than men.22,25,26

In this cohort, when adjusting for sex, nocturia was a more common complaint among older patients. These findings are similar to a study by Fitzgerald et al, who also reported that nocturia was common in a community-based population; on their multivariate analysis, the odds of nocturia increased with age and were lower for men (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65, 0.97).27 However, we found that odds of nocturia were not significantly different across sexes. This could be due to a broader age demographic and to inherent population differences in a treatment-seeking cohort.

This report has several strengths and limitations. As the individuals in this cohort were a fraction of the treatment-seeking patients seen in tertiary care urology or urogynecology clinics and mostly white, our findings may not be generalizable to the general population of patients seeking care with primary care physicians. Our definition of incontinence and incontinence type, as well as LUTS, are based solely on patient self-report and are not corroborated by any objective testing, such as urodynamic studies. This report also did not include controls that were not seeking treatment to serve as a comparison group. Strengths, however, are that this is a very large mixed-sex cohort with detailed medical and surgical history, with duplicative questionnaires covering patients’ urinary symptoms.

Data collected as part of this cohort, but not presented here, contain a wealth of information on many other aspects of participants’ non-urologic history and symptoms that will be used to explore relationships between these and their LUTS. Additionally, studies on biological samples, bladder diaries, and the longitudinal portion of the study will further supplement our understanding of LUTS in this group. Our findings from future reports will be a useful guide to health care providers in the management of LUTS in men and women presenting for treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

The LURN has successfully recruited a large cohort of treatment-seeking men and women with LUTS. The study participants completed a detailed, standardized assessment, which provides a novel opportunity to identify and study LUTS and other potentially associated symptoms that will be the subject of future reports. These initial analyses indicated that LUTS varied widely by sex and age. While this variation was similar to prior population-based studies, prevalence of symptoms was higher in our cohort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This is publication number 4 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK097776, DK099879).

Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (DK097780): PI: Cindy Amundsen, MD, Kevin Weinfurt, PhD; Co-Is: Kathryn Flynn, PhD, Matthew O. Fraser, PhD, Todd Harshbarger, PhD, Eric Jelovsek, MD, Aaron Lentz, MD, Drew Peterson, MD, Nazema Siddiqui, MD, Alison Weidner, MD; Study Coordinators: Carrie Dombeck, MA, Robin Gilliam, MSW, Akira Hayes, Shantae McLean, MPH

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (DK097772): PI: Karl Kreder, MD, MBA, Catherine S Bradley, MD, MSCE, Co-Is: Bradley A. Erickson, MD, MS, Susan K. Lutgendorf, PhD, Vince Magnotta, PhD, Michael A. O’Donnell, MD, Vivian Sung, MD; Study Coordinator: Ahmad Alzubaidi

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK097779): PIs: David Cella, Brian Helfand, MD, PhD; Co-Is: James W Griffith, PhD, Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Christina Lewicky-Gaupp, MD, Todd Parrish, PhD, Jennie Yufen Chen, PhD, Margaret Mueller, MD; Study Coordinators: Sarah Buono, Maria Corona, Beatriz Menendez, Alexis Siurek, Meera Tavathia, Veronica Venezuela, Azra Muftic, Pooja Talaty, Jasmine Nero. Dr. Helfand, Ms. Talaty, and Ms. Nero are at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK099932): PI: J Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSCI; Co-Is: Mitch Berger, MD, PhD, John DeLancey, MD, Dee Fenner, MD, Rick Harris, MD, Steve Harte, PhD, Anne P. Cameron, MD, John Wei, MD; Study Coordinators: Morgen Barroso, Linda Drnek, Greg Mowatt, Julie Tumbarello

University of Washington, Seattle Washington (DK100011): PI: Claire Yang, MD; Co-I: John L. Gore, MD, MS; Study Coordinators: Alice Liu, MPH, Brenda Vicars, RN

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis Missouri (DK100017): PI: Gerald L. Andriole, MD, H. Henry Lai; Co-I: Joshua Shimony, MD, PhD; Study Coordinators: Susan Mueller, RN, BSN, Heather Wilson, LPN, Deborah Ksiazek, BS, Aleksandra Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urology, and Hematology, Bethesda, MD: Project Scientist: Ziya Kirkali MD; Project Officer: John Kusek, PhD; NIH Personnel: Tamara Bavendam, MD, Robert Star, MD, Jenna Norton

Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, Data Coordinating Center (DK097776 and DK099879): PI: Robert Merion, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Victor Andreev, PhD, DSc, Brenda Gillespie, PhD, Gang Liu, PhD, Abigail Smith, PhD; Project Manager: Melissa Fava, MPA, PMP; Clinical Study Process Manager: Peg Hill-Callahan, BS, LSW; Clinical Monitor: Timothy Buck, BS, CCRP; Research Analysts: Margaret Helmuth, MA, Jon Wiseman, MS; Project Associate: Julieanne Lock, MLitt, BA

Heather Van Doren, MFA, senior medical editor with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on this manuscript.

References

- 1.Tennstedt SL, Link CL, Steers WD, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for urine leakage in a racially and ethnically diverse population of adults: The Boston area community health (BACH) survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:390–399. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic Costs of Overactive Bladder in the United States. Urology. 2010;75:526–532.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.096. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milsom I, Kaplan SA, Coyne KS, et al. Effect of bothersome overactive bladder symptoms on health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression, and treatment seeking in the United States: Results from EpiLUTS. Urology. 2012;80:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.004. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaughan CP, Johnson TM, Ala-Lipasti MA, et al. The prevalence of clinically meaningful overactive bladder: Bother and quality of life results from the population-based FINNO study. Eur Urol. 2011;59:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.031. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103:4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lua LL, Pathak P, Dandolu V. Comparing anticholinergic persistence and adherence profiles in overactive bladder patients based on gender, obesity, and major anticholinergic agents. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nau.23256. e pub ahea: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang CC, Weinfurt KP, Merion RM, et al. The Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network. J Urol. 2016;196:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne KS, Barsdorf AI, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:448–454. doi: 10.1002/nau.21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, et al. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2000;11:319–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. Available at: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR) Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a Modified National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index to Assess Genitourinary Pain in Both Men and Women. Urology. 2009;74 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus Negl. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–83. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3153635&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6668417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS™ sleep disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment item banks. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;10:6–24. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.636266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, et al. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:115. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3214824&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, et al. Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber MD, Chen Z, Lukacz E, et al. Further validation of the short form versions of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:541–546. doi: 10.1002/nau.20934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegel BMR, Hays RD, Bolus R, et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.237. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepor H, Machi G. Comparison of aua symptom index in unselected males and females between fifty-five and seventy-nine years of age. Urology. 1993;42:36–40. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-Based Survey of Urinary Incontinence, Overactive Bladder, and Other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Five Countries: Results of the EPIC Study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Matthews C, Conover M, et al. Lifetime Risk of Stress Incontinence or Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery. Obs Gynecol. 2014;123:1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chai TC, Belville WD, McGuire EJ, et al. Specificity of the American Urological Association voiding symptom index: comparison of unselected and selected samples of both sexes. J Urol. 1993;150:1710–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35874-3. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7692107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chancellor MB, Rivas DA. American Urological Association symptom index for women with voiding symptoms: lack of index specificity for benign prostate hyperplasia. J Urol. 1993;150:1706–1709. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35872-x. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/docview/76007612?accountid=14744%5Cnhttp://fama.us.es/search*spi/i?SEARCH=00225347%5Cnhttp://pibserver.us.es/gtb/usuario_acceso.php?centro=$USEG¢ro=%24USEG&d=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FitzGerald MP, Litman HJ, Link CL, et al. The Association of Nocturia With Cardiac Disease, Diabetes, Body Mass Index, Age and Diuretic Use: Results From the BACH Survey. J Urol. 2007;177:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.