Abstract

Consumers of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) are more likely to drive while impaired when compared to alcohol alone consumers. In addition, acute tolerance to the internal cues of feelings of intoxication is known to contribute to maladaptive decisions to drive while impaired. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if there is differential development of acute tolerance for AmED versus alcohol alone for ratings of willingness to drive after alcohol consumption. Social drinkers (n = 12) attended four separate sessions where they received alcohol and energy drinks, alone and in combination. The development of acute tolerance to alcohol was assessed for several objective (a computerized cued go/no-go reaction time task) and subjective measures at matched breath alcohol concentrations (BrAC) for the ascending and descending limbs of the BrAC curve. The results indicated that alcohol administration decreased willingness to drive ratings. Acute tolerance was observed in the AmED dose condition only for the willingness to drive ratings which were significantly higher on the descending versus ascending test. Alcohol-induced impairments of the computer task performance did not exhibit any acute tolerance. Therefore, the differential development of acute tolerance may explain why many studies observe higher rates of impaired driving for AmED consumers as compared to alcohol alone consumers. Since drunk driving is a major public health concern, alcohol consumers should be warned that the use of energy drink mixers with alcohol could lead to a false sense of security in one’s ability to drive after drinking.

Keywords: alcohol, energy drinks, driving, subjective state, acute tolerance

Introduction

The consumption of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) may be riskier than alcohol alone (for a review, see Marczinski & Fillmore, 2016). The addition of highly caffeinated energy drink mixers to alcohol, while a common practice, may lead to greater health and safety risks than would be expected based on the dose of alcohol. For example, one reliable finding in the literature using samples of differing ages from around the world is that consumers of AmED are more likely to be heavier/risky drinkers and are more likely to drive after drinking when compared to alcohol alone consumers (Arria et al., 2016; Bonar et al., 2015; Brache & Stockwell, 2011; Eckschmidt et al., 2013; Martz et al., 2015; O’Brien et al., 2008; Spierer et al., 2014; Thombs et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2016; Woosley et al., 2015a,b). In one field study of U.S. bar patrons, alcohol consumers were asked about their types of drinks consumed that evening (AmED), their intentions to drive upon leaving the bar district, and were asked to provide a breathalyzer reading (Thombs et al., 2010). The results indicated that the AmED consumers were at a 3-fold increased risk of being legally intoxicated as compared to the patrons who did not consume AmED, and the AmED consumers were at a 4-fold increased risk of intending to drive. Given that the association between AmED consumption and driving while impaired is so reliable in the literature, an explanation for this phenomenon is needed.

For alcohol alone, binge drinking is strongly associated with alcohol-impaired driving (Flowers et al., 2008) and driving while intoxicated is more directly related to binge drinking rather than chronic heavy drinking (Borges & Hansen, 1993; Duncan, 1997). Thus, the high rates of impaired driving in AmED consumers may simply reflect excessive use of alcohol (Rossheim et al., 2016). Moreover, heavy drinking is associated with the development of alcohol tolerance or the diminished intensity of the response to a dose of alcohol with repeated administration (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As tolerance develops, higher doses of alcohol may be needed to reinstate the initial effect, which is why tolerance to alcohol is one of the diagnostic criteria for alcohol-related disorders since tolerance contributes to alcohol dependence by encouraging escalating doses. When alcohol consumers drink, they may make decisions to drive in part by how they feel. Tolerance to the subjective impairing effects of alcohol may lead drinkers to think they are more able to drive because they are not feeling the alcohol as much as they used to prior to tolerance development. However, tolerance need not take months or years to develop. In fact, alcohol tolerance can be observed within a single drinking episode (Tabakoff et al., 1986). Acute tolerance is defined as diminished intensity of the response to alcohol later in a drinking episode when compared to the earlier more pronounced intensity of the response to the alcohol measured soon after alcohol administration when blood alcohol is still rising, even if the BAC is the same at both times (Beirness & Vogel-Sprott, 1984; Bennett et al., 1993; Hiltunen & Jarbe, 1990). In the literature, acute tolerance is sometimes referred to as the “Mellanby effect” named for the first demonstration of acute tolerance to alcohol whereby ataxia in dogs was greater for a BAC on the ascending limb of the BAC-time curve as compared to a matched BAC assessment for the declining limb (Mellanby, 1919).

There are two pieces of evidence that suggest that acute tolerance should be examined following AmED consumption to better understand the high rates of impaired driving in AmED consumers. First, the majority of arrests for driving under the influence often occur late at night (Shore et al., 1998) and decisions about whether to drive under the influence are likely to occur when BAC is declining. Toxicological report data from autopsies of drinking drivers who were killed in traffic accidents support this claim (Levine & Smialek, 2000). Data from one sample of driver fatalities where alcohol was present in blood and death occurred shortly after the accident revealed that only 8% of cases were on the ascending limb of the BAC curve and 25% of cases were at the plateau. The majority of cases, specifically 67% of fatalities, were on the declining limb. Since binge drinkers, including AmED consumers, are ingesting high doses of alcohol and timing after alcohol ingestion matters for impaired driving, a study that compares the acute effects of AmED versus alcohol alone when BAC is rising and declining is needed.

The second reason that acute tolerance should be examined following AmED consumption is that a recent systematic review of human laboratory-based studies of the acute alcohol tolerance literature revealed that acute tolerance was most reliably demonstrated for subjective intoxication and willingness to drive ratings (Holland & Ferner, 2017). When BAC is rising, participants feel more intoxicated and report being less willing to drive. However, later in the drinking episode when BAC is declining, participants develop acute tolerance and report feeling less intoxicated and report being more willing to drive. The development of acute tolerance to these subjective ratings does not coincide with actual behavior indicating that the development of acute tolerance is not uniform across all subjective and objective measures (Cromer et al., 2010; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2009; Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). In fact, the objective measures that reflect the skills that would actually be needed for safe driving (i.e., fast and accurate response times, responses to inhibitory cues, and skills measured using driving simulators) are generally collectively as a whole worse on the declining limb as compared to the same BAC on the rising limb. Thus, acute tolerance plays an important role in maladaptive decisions to drive because acute tolerance is more readily observed for subjective state than objective skills (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2009). Importantly for AmED consumers and this current study, alterations in subjective state are frequently reported in laboratory research where the acute effects of AmED versus alcohol alone are compared on a variety of subjective and objective measures (regardless of what BAC position was tested although most studies focus on ascending or peak BAC). After consumption of AmED beverages, participants report feeling less intoxicated, less impaired, more stimulated, and less sedated (for a review, see Marczinski & Fillmore, 2016). However, these subjective reactions do not coincide with better driving. The results of at least one study examining simulated driving for caffeinated alcohol versus alcohol alone indicated that caffeine does not alter BrAC or driving performance when alcohol has been consumed (Howland et al., 2011).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if differential development of acute tolerance occurs for AmED versus alcohol alone may play a role in the heightened risk of impaired driving following AmED consumption. Social drinkers (n = 12) attended four separate sessions where they received alcohol and energy drinks, alone and in combination. The development of acute tolerance to alcohol for subjective willingness to drive ratings was assessed by comparing measures during the ascending and descending phases of the blood alcohol curve. Performance on a cued go/no-go reaction time task and other subjective measures were also tested on these two tests. It was predicted that there may be differential development of acute tolerance for AmED as compared to alcohol alone, particularly for the subjective ratings. It was also predicted that acute tolerance would not be observed for the objective measures from the cued go/no-go reaction time task.

Method

Participants

Twelve adults (7 men and 5 women) between the ages of 21 and 27 years (M = 22.33, SD = 1.67) participated in this study. The self-reported racial makeup of the sample was 1 African-American and 11 white participants. For ethnicity, no participants self-identified as Hispanic. Participants had a mean weight of 77.10 kg (SD = 15.47). Volunteers completed questionnaires that provided demographic information, alcohol and caffeine use habits, and physical and mental health status.

Exclusion criteria included a self-reported psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, head trauma, or other CNS injury. In addition, volunteers with a score of the 5 or higher on the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer et al., 1975) and/or a score of 8 or higher on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Barbor et al., 1989) were also excluded from study participation because of the risk for dependence (Barry & Fleming, 1993; Schmidt et al., 1995). Furthermore, individuals who did not regularly consume alcohol (i.e., fewer than 2 standard drinks per month) were excluded. Inclusion criteria included the self-reported consumption of 1 energy drink in the past year, and having consumed at least 1 caffeinated beverage in the past 2 weeks (e.g., soft drink, tea, coffee, chocolate, and/or energy drink). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and normal color vision. No volunteers used any illicit drugs or were pregnant, as determined by self-report and urine drug testing assessed at the start of each session. Participants were recruited through notices posted on community bulletin boards at the university. All volunteers provided informed consent before participating. The Northern Kentucky University Institutional Review Board approved this study, and volunteers received $130 for their participation in the entire 5 session study.

Apparatus and Materials

Personal Drinking Habits Questionnaire (PDHQ: Vogel-Sprott, 1992)

The PDHQ measures an individual’s current, typical alcohol use habits including: (a) number of standard drinks (i.e., bottles of beer, glasses of wine, and shots of liquor) typically consumed during a single drinking occasion, (b) dose (grams of absolute alcohol per kilogram of body weight typically consumed during a single drinking occasion), (c) weekly frequency of drinking, and (d) hourly duration of a typical drinking occasion. The PDHQ also measures previous experience with alcohol in terms of the number of months that an individual has been drinking on a regular basis or customarily on social occasions.

Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB: Sobell & Sobell, 1992)

The TLFB assesses self-reported daily patterns of alcohol consumption during the past 30 days including maximum number of continuous days of drinking, maximum number of continuous days of abstinence, total number of drinking days, total number of drinks consumed in the past month, highest number of drinks consumed in one day, total number of heavy drinking (5+ drinks) days, and total number of ‘drunk’ days (i.e., days on which the participant self-reported feeling intoxicated).

Caffeine Use Questionnaire (CUQ)

This questionnaire provides a measure of a participant’s daily caffeine consumption in milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Estimates of the caffeine content in foods and beverages were taken from Barone and Roberts (1996), McCusker et al. (2006), and manufacturer websites for newer products.

Impulsivity Measures

Two measures assessed self-reported impulsivity, with higher scores indicating greater impulsivity. The Eysenck Impulsiveness Questionnaire (Eysenck et al., 1985) assesses impulsivity using 19 yes/no questions. The Barrett Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995) assesses impulsivity by asking participants to rate how typical 30 different states are for them on a 4-point Likert scale.

Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES; Martin et al., 1993)

Subjective ratings of stimulation and sedation were evaluated using this 14-adjective rating scale where 7 adjectives describe stimulation effects (e.g., stimulated, elated) while the remaining 7 describe sedation effects (e.g., sedated, sluggish). Participants rated each item on an 11-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) and Stimulation and Sedation scores were summed separately (score subscale range = 0–70).

Subjective Effect Ratings

A 2-item 100 mm visual analogue scale was used to assess the subjective effects of the dose administered with end anchors of not at all and very much. Participants rated their willingness to drive and their overall level of impairment at the time of the rating (Beirness, 1987). A rating of 100 would indicate total willingness to drive and no impairment for these measures. In addition, participants completed an intoxication rating scale (Fillmore & Vogel-Sprott, 2000). Perceived level of intoxication was indicated by the perceived alcoholic content of the beverage administered in terms of bottles of beer containing 5% alcohol. The scale ranges from 0 to 10 bottles of beer, in 0.5 bottle increments. Finally, participants were asked to rate what they would be willing to pay for the beverage they had received. The scale ranges from $0.00 to $10.00, in $0.50 increments.

Cued go/no-go reaction time task

The cued go/no-go reaction time task was used to assess the ability to activate and inhibit responses (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003a,b; Miller et al., 1991). This task is sensitive to the effects of moderate doses of alcohol and energy drinks (Marczinski et al., 2011, 2017). The task was operated using E-Prime 2.0 software (Schneider et al., 2002) on a Dell Latitude laptop computer (Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX). A test consisted of 250 trials involving four possible cue-target combinations and took approximately 15 minutes to complete. A trial involved the following sequence of events: (i) a fixation point (+) for 800 ms, (ii) a blank screen for 500 ms, (iii) a cue (a horizontal or vertical white rectangle), displayed for one of five stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs = 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ms), (iv) a go or no-go target (green or blue rectangle), visible until a response occurred or 1000 ms elapsed, and (v) an intertrial interval of 700 ms.

The cue orientation (horizontal or vertical) correctly indicated the target 80% of the time. Participants were instructed to press the forward slash (/) key on the keyboard as soon as a go (green) target appeared and to suppress (inhibit) any response if a no-go (blue) target appeared. Activational and inhibitory tendencies show rapid development of cue dependence as cues help an individual prepare for the appropriate execution or inhibition of behavior (Miller et al., 1991). For response activation, the acute effects of alcohol typically slow mean reaction times (RT) to go targets, particularly in the invalid no-go cue condition (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003a,b). For response inhibition, the go cue generates the proclivity to prepare to act, yet subjects must overcome this response prepotency to successfully inhibit the response when a no-go target is displayed. Acutely, alcohol impairs response inhibition, particularly in the invalid go cue condition (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003a,b). When alcohol is administered in moderate doses, the co-administration of caffeine/energy drinks have been shown to reduce the impairment by alcohol for response execution (as measured by RTs to go targets) but does not alter the alcohol impairment on response inhibition (as measured by the proportion of failures to inhibit responses to no-go targets) (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003a; Marczinski et al., 2011). Given that the invalid cue conditions are where the acute effects of alcohol and energy drinks will be observed, data analyses will focus on the invalid no-go cue condition for mean RTs and the invalid go cue condition for proportion of failures to inhibit responses.

Procedure

Pre-laboratory Screening

Individuals who responded to the advertisements contacted the research assistant by e-mail to set up a time to participate in a telephone intake-screening interview. During the telephone interview, volunteers were informed that the purpose of the experiment was to study the effects of alcohol and energy drinks on behavioral and mental functioning. Volunteers were told that they would be asked to come to the lab for five sessions to perform computerized tasks and complete paper-and-pencil questionnaires. Moreover, they were informed that they would receive a beverage to consume on all sessions except the first one, and that the beverage they would receive on each session could contain the maximum dose of alcohol found in 4 beers and the maximum dose of caffeine found in a cup of coffee or 2 cans of a soft drink. The research assistant determined if the participant met all eligibility requirements to participate. Before any test session, participants were required to fast for 2 hours, abstain from any form of caffeine for 8 hours, and abstain from alcohol for 24 hours. Eligible subjects then made an appointment for one baseline session and four dose administration sessions.

Baseline Session

Each participant was tested individually by a trained research assistant. Testing occurred between the hours of 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. Testing times within one subject were kept as similar as possible and did not vary more than 4 hours from the baseline session start time. Upon arrival in the lab for the baseline session, the participant was asked to provide informed consent. The participant also completed a general health questionnaire, PDHQ, TLFB, CUQ, Eysenck, and BIS-11 paper-and-pencil questionnaires. The participant was weighed. Finally, the participant practiced the cued go/no-go task on the computer.

Dose Administration Sessions

Sessions two through five were dose administration sessions. At the start of every dose administration, the participant was weighted and completed a medical screening questionnaire to ensure that the participant was healthy and had not recently taken any prescribed or over-the-counter medications. A zero breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) was confirmed using an Intoxilyzer Model 400 (CMI Inc., Owensboro, KY). The participant provided a urine sample in a private bathroom in the lab and the research assistant immediately tested the urine sample for drug metabolites and pregnancy (women only). For drug metabolites, the testing was for benzodiazepines, barbiturates, tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, amphetamines, and opiates (uVera Diagnostics, Inc., Norfolk, VA).

On each test day, the participant received one of four possible doses: (1) 1.97 ml/kg vodka + 3.94 ml/kg decaffeinated soft drink, (2) 1.97 ml/kg vodka + 3.94 ml/kg energy drink, (3) 3.94 ml/kg decaffeinated soft drink, and (4) 3.94 ml/kg energy drink. Dose administration was single blind as the research assistant was monitoring BrACs and dose order was counterbalanced between subjects. Doses were calculated by body weight and the alcohol doses were reduced by 87% for female participants. For the alcohol doses, the 1.97 ml/kg vodka (40% alcohol/volume Smirnoff Red Label vodka, No. 21, Smirnoff Co., Norwalk, CT) was chosen as this dose results in a moderate peak BrAC of approximately .08 g% (Marczinski et al., 2011) which is the U.S. legal limit for driving.. The alcohol doses were mixed with either Squirt (Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, Plano, TX), a decaffeinated carbonated soft drink or with Red Bull energy drink (Red Bull, Switzerland). In the control conditions where the energy drink or decaffeinated soft drink was consumed, 10 ml of vodka was floated on the surface of the beverage to give the drink an alcoholic scent (Marczinski et al., 2011). Participants were informed that they might receive alcohol, energy drink, decaffeinated soft drink or a combination of these during all of the test sessions. However, the exact contents of the beverages were never disclosed to the participants during the course of the study.

Participants were given their beverage in a plastic cup and were asked to consume the drink within 10 minutes. Drinking was self-paced. After dose administration, participants relaxed and read magazines. BACs were measured at 30, 40, 50, 60, 75, 90, 100, 110, and 140 min. after drinking. Participants also provided breath samples at those times during sessions where no alcohol was administered. Based on previous work examining acute tolerance using the same dose of alcohol and administration procedures (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2009), the peak BrAC for the alcohol conditions was expected to be approximately .08 g% and to occur at approximately 60 minutes after drinking began. The ascending limb and descending testing battery occurred at 30 and 90 minutes after drinking began as BrACs were expected to be approximately .06-.07 g% and match at those times, also based on previous work (Marczinski & Fillmore, 2009). For both ascending and descending limb tests, participants completed the cued go/no-go task, the BAES, the willingness to drive rating, and impairment rating. For the descending limb test, participants also completed the intoxication and pay ratings.

Upon completion of the testing period, participants relaxed in a waiting room in the laboratory. Participants received a hot meal and snacks and remained at leisure to read magazines or watch DVDs until their BrAC fell below .02 g%., at which time they were released. Participants who had not received alcohol were immediately released after the testing battery concluded. All participants were paid and debriefed following the completion of the final session.

Data Analyses

For the dependent measures obtained, the data were submitted to separate 2 (Alcohol Dose: 1.97 ml/kg vodka v. 0.00 ml/kg vodka) × 2 (Energy Drink: 3.94 ml/kg energy drink × 3.94 ml/kg decaffeinated soft drink) × 2 (Test: Ascending Limb v. Descending Limb) within-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Sex was included as an initial between-subjects factor for all initial analyses but no main effects or interactions with sex were obtained for the measures after dose administration. Given the small sample size and focus on measuring acute tolerance that required three-way ANOVA analyses, sex is only reported for the analyses of the drinking habits where sex differences could be anticipated. The alpha level was set at .05 for all statistical tests and SPSS 17.0 was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Demographic Characteristics and Self-reported Caffeine and Alcohol Use

Table 1 provides all demographic and baseline questionnaire measures for the male and female participants. Possible sex differences in these baseline measures were tested using two-tailed independent samples t tests. Results revealed that males weighed significantly more than females, t(10) = 4.39, p = .001. Also, males self-reported a longer history of drinking alcohol compared to the females, t(10) = 2.52, p = .030. No other significant differences on any of the other alcohol use, caffeine use, or impulsivity measures were observed (ps > .14).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and self-reported alcohol/caffeine use for the male (n = 7) and female (n = 5) participants.

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 22.86 | 2.04 | 21.60 | 0.55 |

| Weight (kg) | 87.26 | 8.54 | 62.88 | 10.72 |

| Body Mass Index | 26.99 | 3.35 | 22.36 | 4.43 |

| Daily caffeine use (mg/kg) | 1.63 | 1.61 | 3.21 | 1.27 |

| SMAST | 1.00 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AUDIT | 8.00 | 5.69 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| Eysenck | 6.71 | 4.00 | 3.20 | 4.97 |

| BIS-11 | 59.43 | 5.06 | 45.80 | 10.01 |

| Personal Drinking Habits Questionnaire (PDHQ): | ||||

| History (months) | 75.57 | 30.83 | 38.40 | 12.58 |

| Frequency (occasions/week) | 1.43 | 0.53 | 1.05 | 0.67 |

| Alcohol dose (g/kg) | 1.47 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 0.64 |

| Duration (hour) | 5.14 | 2.48 | 4.00 | 0.79 |

| Timeline Follow-back (TLFB): | ||||

| Continuous drinking days | 2.29 | 1.98 | 1.20 | 0.45 |

| Continuous abstinence days | 7.57 | 1.40 | 12.60 | 5.51 |

| Total no. drinking days | 6.71 | 3.86 | 3.60 | 2.19 |

| Total no. drinks | 51.14 | 52.05 | 10.00 | 6.04 |

| Highest no. drinks in 1 day | 9.71 | 5.62 | 4.80 | 2.59 |

| Heavy drinking days | 4.29 | 4.19 | 0.60 | 0.89 |

| Drunk days | 3.57 | 3.60 | 1.40 | 1.67 |

Breath Alcohol Concentrations

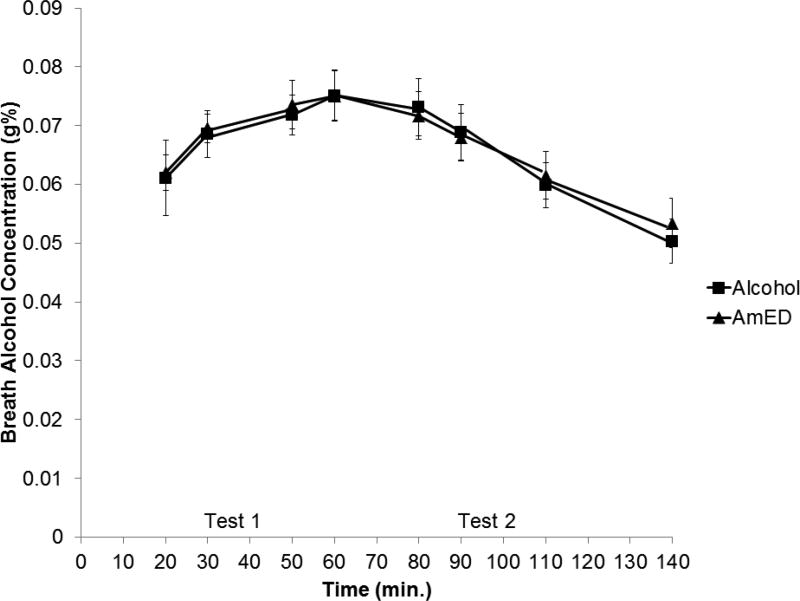

No detectable BrACs were observed under the placebo or energy drink conditions. BrACs obtained in the 2 active alcohol dose conditions were examined by a 2 (Energy Drink) × 8 (Time) within-subjects ANOVA. The means are presented in Figure 1. A main effect of time, F(7,77) = 10.98, p < .001, η2 = .499 was obtained, as BrACs rose and then declined during the course of the session. There was no main effect of energy drink and no energy drink by time interaction, ps > .772. To confirm that BrACs were approximately equivalent during the rising limb test (test 1) and declining limb test (test 2) for both alcohol dose conditions, BrACs recorded at 30 and 50 min. were averaged (for test 1) and BrACs recorded at 90 and 110 min. were averaged (for test 2) for each alcohol dose condition. Mean BrACs were .07 g% and .06 g% for tests 1 and 2, respectively, in the alcohol alone dose condition, and .07 g% and .06 g% for tests 1 and 2, respectively, for the AmED dose condition. A difference score was created by subtracting test 2 from test 1 BrACs. A paired samples t test on these difference scores indicated that there was no difference between alcohol and AmED conditions, t(11) = − 0.26, p = .803.

Figure 1.

Mean breath alcohol concentration (g%) following alcohol and alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) administration. Vertical bars show standard errors of the mean.

Cued Go/No-go Task Performance

Table 2 reports the mean (SD) values for the mean RTs and p-inhibition failures under all four dose conditions for each test. The results of a 2 (Alcohol) × 2 (Energy Drink) × 2 (Test) within-subjects ANOVA for mean RTs for the invalid no-go cue condition revealed a significant main effects of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 5.31, p = .042, η2 = .325, and a significant main effect of Test, F(1,11) = 7.00, p = .023, η2 = .389. There were no other main effects or interactions, ps > .052. The main effect of Alcohol reflected slower mean RTs for the alcohol conditions (M = 328.77) as compared to when alcohol was not administered (M = 302.99). The main effect of Test reflected slower mean RTs for the test 2 (M = 325.80) as compared to test 1 (M = 305.95).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) self-reported subjective ratings and cued go/no-go reaction time task performance under all four dose conditions for test 1 (ascending limb) and test 2 (descending limb).

| Dose Conditions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| 0.00 ml/kg Alcohol | 1.97 ml/kg Alcohol (40% abv. vodka) |

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

| 3.94 ml/kg Placebo |

3.94 ml/kg Energy Drink |

3.94 ml/kg Placebo |

3.94 ml/kg Energy Drink |

|||||

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Cued go/no-go task: | ||||||||

| Test 1 no-go cue RT (msec.) | 305.50 | 36.69 | 296.89 | 30.14 | 311.78 | 53.47 | 296.35 | 71.00 |

| Test 2 no-go cue RT (msec.) | 305.97 | 46.21 | 303.58 | 41.15 | 352.47 | 85.23 | 341.18 | 80.70 |

| Test 1 no-go cue p-inhibitory failures | 0.14 | .012 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Test 2 no-go cue p-inhibitory failures | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

| Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES): | ||||||||

| Test 1 Stimulation | 18.08 | 13.77 | 20.83 | 12.25 | 27.58 | 11.57 | 31.92 | 9.83 |

| Test 2 Stimulation | 16.00 | 13.36 | 22.75 | 14.05 | 19.25 | 9.45 | 26.58 | 11.07 |

| Test 1 Sedation | 17.00 | 12.08 | 15.33 | 14.76 | 26.83 | 12.37 | 28.58 | 14.53 |

| Test 2 Sedation | 18.25 | 13.49 | 14.92 | 12.82 | 34.75 | 13.29 | 30.08 | 15.05 |

| Test 1 Willingness to Drive | 98.25 | 3.60 | 88.50 | 20.41 | 17.58 | 20.15 | 11.83 | 17.16 |

| Test 2 Willingness to Drive | 98.42 | 3.99 | 94.17 | 14.34 | 22.08 | 23.33 | 34.08 | 30.85 |

| Test 1 Impairment | 3.00 | 7.39 | 7.58 | 14.89 | 71.42 | 18.75 | 69.08 | 18.67 |

| Test 2 Impairment | 5.42 | 12.19 | 10.08 | 12.81 | 52.92 | 22.90 | 49.50 | 15.77 |

| Intoxication | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 3.67 | 1.40 | 2.88 | 1.79 |

| Willing to Pay | 0.75 | 0.84 | 1.67 | 1.57 | 2.58 | 1.64 | 3.38 | 1.69 |

The results of a 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA for p-inhibition failures for the invalid go cue condition revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 10.48, p = .008, η2 = .488. There were no other significant main effects or interactions for this analysis, ps > .410. The main of Alcohol reflected greater p-inhibitory failures for the alcohol conditions (M = 0.23) as compared to when alcohol was not administered (M = 0.14).

Subjective Ratings

Mean (SD) values for all subjective ratings under all four dose conditions for each test are reported in Table 2. The results of a 2 × 2 × 2 within-subjects ANOVA for Stimulation ratings revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 6.59, p = .026, η2 = .374, and a significant Alcohol × Test interaction, F(1,11) = 8.68, p = .013, η2 = .441. There were no other main effects or interactions, ps > .050. The Alcohol × Test interaction reflected higher stimulation ratings for test 1 (M = 29.75) versus test 2 (M = 22.92) for the alcohol conditions, which was confirmed with a paired samples, t(11) = 2.90, p = .015. By contrast, stimulation ratings for test 1 (M = 19.46) and test 2 (M = 19.38) were relatively similar when alcohol was not administered, t(11) = 0.06, p = .954.

The results of a 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA for Sedation scores revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 13.25, p = .004, η2 = .546. There were no other main effects or interactions for this analysis, ps > .149. The main effect of alcohol reflected higher sedation ratings when alcohol was administered (M = 30.06) versus conditions with no alcohol (M = 16.38).

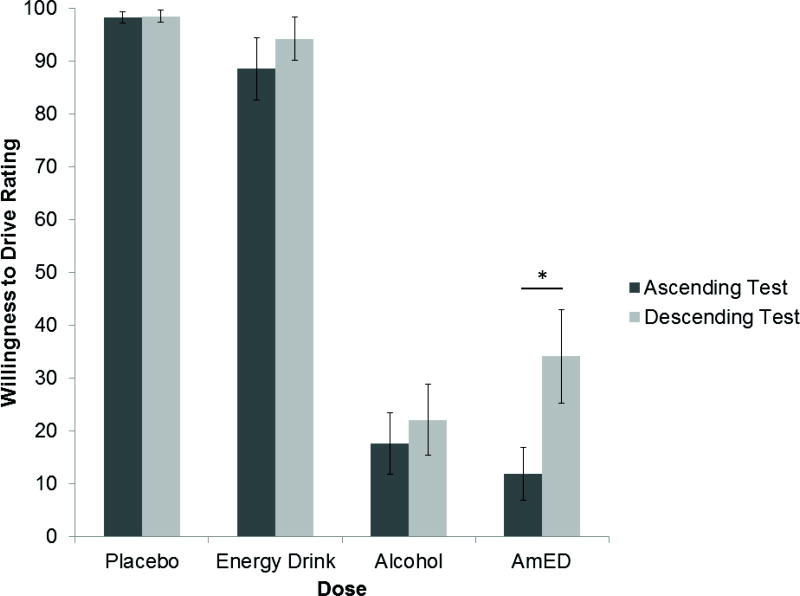

The results of a 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA for Willingness to Drive ratings revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 145.29, p < .001, η2 = .930, a significant main effect of Test, F(1,11) = 17.24, p = .002, η2 = .610, and a significant Energy Drink × Test interaction, F(1,11) = 15.21, p = .002, η2 = .580. There were no other main effects or interactions for this analysis, ps > .054. Figure 2 presents the mean willingness to drive ratings under each dose and test. The figure illustrates the main effect of alcohol where willingness to drive ratings were significantly lower after alcohol administration (M = 21.40) versus no (M = 94.83). Given the interest in assessing the development of acute tolerance, paired samples t-tests were conducted to compare tests 1 and 2 for each dose condition. The results indicated that for the AmED condition, test 2 willingness to drive ratings were significantly higher than test 1, t(11) = −3.56, p = .005. By contrast, test 1 and 2 willingness to drive ratings did not differ for any other conditions, ps > .132.

Figure 2.

Mean Willingness to Drive ratings for the Ascending Limb and Descending Limb tests under all dose conditions. Vertical bars show standard errors of the mean. * indicates a significant difference between the two tests for the AmED condition (p = .005).

The results of a 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA for Impairment ratings revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 128.89, p < .001, η2 = .921, a significant main effect of Test, F(1,11) = 6.85, p = .024, η2 = .384, and a significant Alcohol × Test interaction, F(1,11) = 22.94, p = .001, η2 = .676. There were no other main effects or interactions for this analysis, ps > .189. The Alcohol × Test interaction reflected higher impairment ratings for test 1 (M = 70.25) versus test 2 (M = 51.21) for the alcohol conditions. A paired samples t-test confirmed that test 1 scores were significantly higher than test 2 scores for the alcohol conditions, t(11) = 5.00, p < .001. By contrast, impairment ratings for test 1 (M = 5.29) and test 2 (M = 7.75) were low and relatively similar when alcohol was not administered, t(11) = −0.62, p = .547.

The results of a 2 (Alcohol) × 2 (Energy Drink) ANOVA for Intoxication ratings revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 55.56, p < .001, η2 = .835, and a significant Alcohol × Energy Drink interaction, F(1,11) = 13.53, p = .004, η2 = .551. There was no main effect of Energy Drink, p = .497. The Alcohol × Energy Drink interaction reflected lower intoxication ratings in the AmED condition (M = 2.88) versus the alcohol alone condition (M = 3.67), which was confirmed with a paired samples t-test, t(11) = 2.55, p = .027. By contrast, intoxication ratings for placebo (M = 0.00) and energy drink alone (M = 0.46) were low and not significantly different, t(11) = − 1.69, p = .119.

Finally, the results of a 2 (Alcohol) × 2 (Energy Drink) ANOVA for Willingness to Pay ratings revealed a significant main effect of Alcohol, F(1,11) = 13.12, p = .004, η2 = .544, and a significant main effect of Energy Drink, F(1,11) = 5.37, p = .041, η2 = .328. There was no interaction, p = .828. The main effect of alcohol reflected participant ratings that they would be willing to pay more for alcoholic drinks (M = $2.98) versus drinks with no alcohol (M = $1.21). The main effect of energy drink reflected that participant would pay more for energy drinks (M = $2.52) versus drinks made with the decaffeinated soft drink (M = $1.67).

Discussion

The results of the current study indicated that alcohol (alone and in combination with energy drinks) decreased willingness to drive ratings for each test compared to conditions where no alcohol was administered. However, on the descending limb test, AmED administration resulted in significantly higher willingness to drive ratings compared to the ascending limb test (indicating development of acute tolerance). This result was not observed for alcohol alone where ascending and descending limb willingness to drive ratings were similar. When participants were asked on the descending limb test about their perceived level of intoxication using a scale that asked them how many standard drinks they thought they had consumed, participants indicated they felt less intoxicated after AmED versus alcohol alone. For the subjective rating of impairment, there was evidence for acute tolerance to alcohol as impairment ratings were lower on the descending limb test as compared to the ascending limb test for the alcohol conditions. However, no differences in limb tests for alcohol versus AmED were observed for the measure of impairment indicating that acute tolerance developed uniformly for both alcohol and AmED for this measure. Thus, the results for the willingness to drive and intoxication measures provide some indication why AmED consumers might be more likely to engage in impaired driving in the real world. AmED consumers may feel less intoxicated and are more willing to drive and this is in addition to general acute tolerance to feelings of impairment that generally occurs after alcohol administration.

Importantly in the results, any acute tolerance for measures of perceived state under alcohol does not appear to reflect any changes in cognitive and behavioral skills that would be needed to drive with effectiveness. For the cued go/no-go task performance, alcohol administration resulted in slower RTs and increased inhibitory failures and these impairments were maintained regardless of when testing occurred. Thus, the differential development of acute tolerance to AmED versus alcohol alone may explain why many studies observe higher rates of impaired driving for AmED consumers as compared to alcohol alone consumers. AmED consumers are not feeling the subjective impairment to the same degree as alcohol alone consumers, yet all alcohol consumers display behavioral impairment after ingesting alcohol.

In the current study, dose administration was controlled so that acute tolerance can be assessed by comparing matched BrACs as BrAC rises versus falls. However, we recently reported a lab study where we observed that self-paced consumption of AmED beverages is typically faster than alcohol alone when measured in the same drinker (Marczinski et al., 2017). This occurs since AmED beverages are more rewarding and reinforcing than alcohol alone (Marczinski et al., 2013, 2016). Even with alcohol alone, individuals vary in the speed of alcohol intake which will determine how quickly BrAC rises. In one laboratory study of social drinkers who ingested a moderate dose of alcohol, faster increases in BrAC on the ascending limb were associated with greater acute tolerance for ratings of subjective intoxication (Morris et al., 2017). As such, the differential development of acute tolerance for AmED versus alcohol alone observed for willingness to drive ratings in the current study may actually underestimate what is occurring when real drinkers can drink at a self-desired pace. It would be important for further work to examine if self-paced drinking results in greater effects for willingness to drive than that observed in the current study.

While every study has limitations, a few specific limitations should be noted. In the current study, the peak BrAC reached was just below .08 g% (i.e., the legal limit for driving in the U.S.). With alcohol administration studies, keeping BrAC within a moderate range ensures participant safety but impaired driving in the real world reflects situations where BrAC is much higher. It would be very important to replicate these findings using varying doses of alcohol and energy drinks to increase the ecological validity of these current results. Another limitation in this study is that we recruited a small non-diverse sample of social drinkers with homogenous drinking habits and who vary on personality traits including impulsivity and sensation seeking. Future work should examine heavier drinkers that may be more tolerant to the alcohol-impairing effects for both subjective and objective measures. Finally, a third study limitation is that we only assessed the measures of perceived intoxication (i.e., how many standard drinks do you think you were given) and willingness to pay (i.e., how much would you pay for the drink you were given) on the descending limb test. Moreover, we did not include a measure of perceived dangerousness of driving measure that others have used to detect acute tolerance reliably in alcohol studies (Amlung et al., 2014). When designing the study, we were concerned that participants would not vary their scores from their initial rating on the perceived intoxication and willingness to pay items since these measures may not fluctuate when compared to measures that can be assessed repeatedly (i.e., sedation, willingness to drive at the time of the rating). It remains unclear if perceived intoxication or willingness to pay ratings could fluctuate within one dose administration session and whether other measures might similarly or better measure willingness to drive following alcohol consumption.

In sum, the current study provides laboratory evidence that there is differential development of acute tolerance for AmED versus alcohol alone. Acute tolerance is already known to play a role in impaired driving decisions and the current study extends this work to suggest that AmED consumption may lead to greater acute tolerance for the willingness to drive versus alcohol alone. This provides a partial explanation of why AmED consumers are more likely to drive impaired. As AmED consumers also drink higher doses of alcohol than alcohol consumers, it is likely that both binge drinking and acute tolerance are leading to impaired driving. Prevention programs should communicate this information to alcohol consumers in efforts to reduce the harms and hazards of alcohol use.

Public Health Significance.

Consumers of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) are more likely to drive while impaired when compared to alcohol alone consumers. This laboratory study demonstrated that AmED administration resulted in significantly higher willingness to drive ratings when breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) was declining as compared to the same BrAC earlier in the drinking episode when BrAC was rising. This result was not observed for alcohol alone where ascending and descending limb willingness to drive ratings were similar.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by NIH grants AA019795 and GM103436 awarded to CA Marczinski. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Some of the ideas and data appearing in this manuscript were presented at the 2012 Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism in San Francisco, CA. An abstract from this poster presentation was published in a journal supplement associated with this meeting (Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36S1, 139A).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Morris DH, McCarthy DM. Effects of acute alcohol tolerance on perceptions of danger and willingness to drive after drinking. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:4271–4279. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE. Energy drink use patterns among young adults: Associations with drunk driving. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:2456–2466. doi: 10.1111/acer.13229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. WHO/MNH/DAT 89.4. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1989. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. [Google Scholar]

- Barone JJ, Roberts HR. Caffeine consumption. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1996;34:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry KL, Fleming MF. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and the SMAST-13: predictive validity in a rural primary care sample. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1993;23:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirness DJ, Vogel-Sprott M. The development of alcohol tolerance: Acute recovery as a predictor. Psychopharmacology. 1984;84:398–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00555220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RH, Cherek DR, Spiga R. Acute and chronic alcohol tolerance in humans: Effects of dose and consecutive days of exposure. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:740–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LK, Fendrich M, Chen HY, Arria AM, Cisler RA. Sociodemographic correlates of energy drink consumption with and without alcohol: results of a community survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonar EE, Cunningham RM, Polshkova S, Chermack ST, Blow FC, Walton MA. Alcohol and energy drink use among adolescents seeking emergency department care. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;43:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges NJ, Hansen SL. Correlation between college students’ driving offenses and their risks for alcohol problems. Journal of American College Health. 1993;42:79–81. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1993.9940464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromer JR, Cromer JA, Maruff P, Snyder PJ. Perception of alcohol intoxication shows acute tolerance while executive functions remain impaired. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:329–339. doi: 10.1037/a0019591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DF. Chronic drinking, binge drinking and drunk driving. Psychological Reports. 1997;80:681–682. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckschmidt F, de Andrade AG, dos Santos B, de Oliveira LG. The effects of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) on traffic behaviors among Brazilian college students: a national survey. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2013;14:671–679. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.755261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsop JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SE, de Mello MT, Pompeia S, de Souza-Formigoni MLO. Effects of energy drink ingestion on alcohol intoxication. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Vogel-Sprott M. Behavioral effects of combining alcohol and caffeine: the contribution of alcohol-related expectancies. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;7:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers NT, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Elder RW, Shults RA, Jiles R. Patterns of alcohol consumption and alcohol-impaired driving in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:639–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudin R, Nicastro R. Can caffeine antagonize alcohol-induced performance decrements in humans? Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1988;67:375–391. doi: 10.2466/pms.1988.67.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltunen AJ, Jarbe TUC. Acute tolerance to ethanol using drug discrimination and open-field procedures in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1990;102:207–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02245923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland MG, Ferner RE. A systematic review of the evidence for acute tolerance to alcohol – the “Mellanby effect”. Clinical Toxicology. 2017;55:545–556. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1296576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway FA. Lose-dose alcohol effects on human behavior and performance. Alcohol, Drugs, and Driving. 1995;11:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Arnedt JT, Bliss CA, Hunt SK, Vehige Calise T, Heeren T, Winter M, Littlefield C, Gottlieb DJ. The acute effects of caffeinated versus non-caffeinated alcoholic beverage on driving performance and attention/reaction time. Addiction. 2010;106:335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AW. Status of alcohol absorption among drinking drivers. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1990;14:198–200. doi: 10.1093/jat/14.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Smialek JE. Status of alcohol absorption in drinking drivers killed in traffic accidents. Journal of Forensic Science. 2000;45:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003a;11:228–236. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Preresponse cues reduce the impairing effects of alcohol on the execution and suppression of responses. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003b;11:110–117. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Clubgoers and their trendy cocktails: Implications of mixing caffeine into alcohol on information processing and subjective reports of intoxication. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:450–458. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol tolerance on subjective intoxication and simulated driving performance in binge drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:238–247. doi: 10.1037/a0014633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Energy drinks mixed with alcohol: What are the risks? Nutrition Reviews. 2014;72(S1):98–107. doi: 10.1111/nure.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Bardgett ME, Howard MA. Effects of energy drinks mixed with alcohol on behavioral control: Risks for college students consuming trendy cocktails. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1282–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Henges AL, Ramsey MA, Young CR. Mixing an energy drink with an alcoholic beverage increases motivation for more alcohol in college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:276–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Maloney SF, Stamates AL. Faster self-paced rate of drinking for alcohol mixed with energy drinks versus alcohol alone. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017;31:154–161. doi: 10.1037/adb0000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Stamates AL, Maloney SF. The desire to drink alcohol is enhanced with high caffeine energy drink mixers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:1982–1990. doi: 10.1111/acer.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM. Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz ME, Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol mixed with energy drink use among U.S. 12th-grade students: prevalence, correlates, and associations with unsafe driving. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker RR, Goldberger BA, Cone EJ. Caffeine content of energy drinks, carbonated sodas, and other beverages. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2006;30:112–114. doi: 10.1093/jat/30.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellanby E. Special report series No. 31. London: Medical Research Committee 1919 [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Schaffer R, Hackley SA. Effects of preliminary information in a go versus no-go task. Acta Psychologica. 1991;76:241–292. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(91)90022-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH, Amlung MT, Tsai CL, McCarthy DM. Association between overall rate of change in rising breath alcohol concentration and the magnitude of acute tolerance of subjective intoxication via the Mellanby method. Human Psychopharmacology. 2017;32 doi: 10.1002/hup.2565. article in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MC, McCoy TP, Rhodes SD, Wagoner A, Wolfson M. Caffeinated cocktails: Energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college students. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15:453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossheim ME, Thombs DL, Weiler RM, Barry AE, Suzuki S, Walters ST, Barnett TE, Paxton RK, Pealer LN, Cannell B. Alcohol mixed with energy drink: Use may be a consequence of heavy drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;57:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Barry KL, Fleming MF. Detection of problem drinkers: the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) Southern Medicine Journal. 1995;88:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Eschman A, Zuccolotto A. E-Prime User’s Guide. Pittsburgh, PA: Psychology Software Tools; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer ML, Vinokur A, Van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore ER, McCoy ML, Toonen LA, Kuntz EJ. Arrests of women for driving under the influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1988;49:7–10. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biomedical Methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spierer DK, Blanding N, Santella A. Energy drink consumption and associated health behaviors among university students in an urban setting. Journal of Community Health. 2014;39:132–138. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakoff B, Cornell N, Hoffman PL. Alcohol tolerance. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1986;15:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, O’Mara RJ, Tsukamoto M, Rossheim ME, Weiler RM, Merves ML, Goldberger BA. Event-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Troxel WM, Ewing BA, D’Amico EJ. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Associations with risky drinking and functioning in high school. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;167:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel-Sprott M. Alcohol Tolerance and Social Drinking: Learning the Consequences. New York, NY: Guilford; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Acute tolerance to alcohol impairment of behavioral and cognitive mechanisms related to driving: drinking and driving on the descending limb. Psychopharmacology. 2012;220:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2519-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey CL, Jacobson BH, Williams RD, Jr, Barry AE, Davidson RT, Evans MW, Jr, Beck NC. A comparison on the combined-use of alcohol & energy drinks to alcohol-only on high-risk drinking and driving behaviors. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015a;50:1–7. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.935948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey CL, Williams RD, Jr, Housman JM, Barry AE, Jacobson BH, Evans MW., Jr Combined use of alcohol and energy drinks increases participation in high-risk drinking and driving behaviors among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015b;76:615–619. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]