Abstract

Ethnic-racial identity (ERI) development and ethnic-racial discrimination are two salient experiences among adolescents in the U.S. Despite growing awareness of the costs and benefits of these experiences individually, we know little about how they may influence one another. The current study examined competing hypotheses relating discrimination and components of ERI (i.e., exploration, resolution, affirmation) among a sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (N = 181; Mage at W1 = 16.83, SD = 1.01) across 6-waves of data. Findings revealed that within-person changes in discrimination predicted subsequent ERI resolution and affirmation; however, ERI did not predict subsequent discrimination. Between-person effects of discrimination on affirmation were significant. Our findings underscore the importance of discrimination experiences in shaping Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ normative developmental competencies.

Keywords: Discrimination, Ethnic-Racial Identity, Latinas, Adolescent Mothers, Within-Person Effects

Discrimination is a common experience for ethnic-racial minority youth in the United States (Umaña-Taylor, 2016) and has been consistently linked to adverse mental and physical health outcomes (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Ethnic-racial identity (ERI) formation, a central aspect of positive youth development that is particularly salient during adolescence (Spencer, 1995; Swanson, Spencer, Dell’Angelo, Harpalani, & Spencer, 2002; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014; Williams, Tolan, Durkee, Francois, & Anderson, 2012), has been found to relate to adolescent well-being and, in some instances, has been found to buffer the adverse effects of discrimination (see Marks, Ejesi, McCullough, & García Coll, 2015 for an overview). Few studies, however, have focused on the interrelation and bidirectional associations of ERI and discrimination, limiting our knowledge about how these two salient constructs may co-occur and affect one another over time. Do experiences of discrimination inform the development of adolescents’ ERI? Do components of ERI inform the adolescents’ future perceptions of discrimination?

The current study examined the concurrent and prospective longitudinal associations between components of ERI (i.e., exploration, resolution, and affirmation) and perceived discrimination using six waves of data. We examined these relations in a sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, a population in which ERI and discrimination processes may be particularly important and salient. First, the transition to motherhood heightens aspects of cultural socialization (Hughes et al., 2006) which, for adolescent mothers, may result in a greater reflection on their own ERI. These heightened feelings may also be occurring alongside cognitive processes that illuminate discrimination experiences in and outside of school contexts (Brown & Bigler, 2005), and may be amplified given that ethnic minority adolescent mothers also face discrimination based on their off-time pregnancy/parenting status (considered a stigmatized status; Brown & Bigler). Understanding the ways that adolescent mothers navigate ERI and discrimination processes during this sensitive developmental period may provide information about developmental processes among a particularly vulnerable group (Borkowski et al., 2002; Deal & Holt, 1998). The focus on U.S.-Mexican adolescent mothers is further important given that Mexican-origin individuals make up a majority of the U.S. Latino population, and Mexican-origin adolescents have the highest teenage birth rate in the U.S. (Martin et al., 2012).

Theoretical Frameworks Linking Discrimination and ERI

Discrimination and ERI research continues to document the importance of each of these constructs in adolescent development. There remains, however, very little work examining how discrimination and ERI are interrelated or inform one another over time. Given the interrelation between individuals and their contexts, it is logical to expect that contextual experiences, such as discrimination, and self-reflective processes, such as ERI, are interrelated (García Coll et al., 1996). Developmentally, ERI processes come to the forefront in adolescence (Erikson, 1968) when perceptions of discrimination are also increasing (Brown & Bigler, 2005; Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006). Indeed, the ability to reflect on one’s identity and perceive discrimination both rely, in part, on cognitive and social perspective-taking abilities that emerge during adolescence (Marks et al., 2015; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997; Quintana, 1998). Despite the sound theoretical foundations for the interrelation of discrimination and ERI, it remains unclear how directionality within this relation plays out over time; do perceptions of discrimination inform ERI, or do aspects of ERI inform the degree to which youth perceive discrimination?

Discrimination as a Predictor of ERI

A large and diverse set of theoretical models suggest that perceptions of discrimination likely inform subsequent ERI. For instance, the phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST) characterizes ERI as an adaptive coping response to contextual risk factors, such as ethnic-racial bias (Spencer, 1995). When individuals encounter discrimination, they draw meaning from these experiences, which informs subsequent self-organizational processes, such as identity (Spencer, 2006). Similarly, the rejection-identification model proposes that individuals are inherently motivated to seek social inclusion; therefore, experiences of discrimination promote subsequent identification with one’s stigmatized group as a mechanism by which to preserve psychological well-being (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Thus, discrimination experiences motivate individuals to orient themselves towards the stigmatized group to provide social sanctuary and comfort. Similarly, Cross’ (1995) model of racial identity suggests that discrimination may initiate engagement in ERI processes; ERI development is spurred by “encounter” experiences in which, confronted with the social, political, and/or historical meaning of one’s ethnicity/race, one begins the process of evaluating the personal meaning of one’s ethnicity-race.

ERI as a Predictor of Discrimination

In contrast to the above ideas, Sellers and colleagues (1998) have discussed ERI as a lens through which the world is viewed and one that is critical to individuals’ overall self-concept. Sellers, Morgan, and Brown (2001) further argue that individuals who feel that ERI is more central to their sense of self, may be more aware of prejudice and discrimination against their ethnic group and, in turn, more likely to perceive discrimination than their peers for whom ERI is less central. Relatedly, individuals who are exploring their ethnic-racial background and identity may become more aware of historical mistreatment and, in turn, more attuned to personal experiences of discrimination.

Empirical Work Linking Discrimination and ERI

Most of the empirical work examining associations between perceived discrimination and ERI components has been cross-sectional and suggests a relation, both positive and negative, between discrimination and ERI components. For instance, Romero and Roberts (2003) found a negative association between perceived discrimination and ERI exploration and affirmation among a sample of Mexican-origin youth. In contrast, Umaña-Taylor and Updegraff (2007) found a positive association between perceived discrimination and ERI exploration, and no association between perceived discrimination and ERI resolution among a sample of Latino adolescents. As for longitudinal work, Umaña-Taylor and Guimond (2010) found that discrimination did not predict longitudinal changes in Latino youths’ ERI exploration. Pahl and Way (2006) found that perceived discrimination was positively associated with within-person growth in ERI exploration among a sample of Black adolescents, but not among Latino adolescents. With respect to ERI resolution, Umaña-Taylor and Guimond (2010) found that discrimination did not predict longitudinal growth in Latino adolescents’ ERI resolution, whereas Fuller-Rowell, Ong, and Phinney (2013) found that perceived discrimination was negatively related to growth in ERI resolution among Latino college students with a strong American identity, but positively related among those with a weak American identity. As for ethnic-racial affect (i.e., positive affect about one’s ethnic-racial group membership), Seaton, Yip, and Sellers (2009) found a negative association with perceptions of discrimination among African American youth during late adolescence.

Few empirical studies have examined whether ERI predicts subsequent discrimination. Although Pahl and Way (2006) originally hypothesized that perceived discrimination would predict increases in exploration among a sample of Black and Latino adolescents, they also tested an alternate model in which exploration predicted within-person growth in perceived discrimination, but found no support for this direction. Likewise, Seaton and colleagues tested an alternate model in which positive ethnic-racial affect predicted subsequent discrimination among a sample of African Americans, but also found that this directionality was not supported (Seaton et al., 2009). Finally, Hou, Kim, Wang, Shen, and Orozco-Lapray (2015) found that perceived discrimination predicted positive ethnic-racial affect in early adolescence, but also found that positive ethnic-racial affect negatively predicted discrimination in middle adolescence among a sample of Chinese Americans.

Taken together, theory and empirical evidence provide a stronger justification for the hypothesis that perceived discrimination predicts subsequent ERI. Note, however, that few studies have considered the alternative hypothesis, that ERI predicts subsequent discrimination, thus limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about directionality. From a methodological perspective, the existing literature is also limited by the nearly exclusive focus on between-person designs (a notable exception is Pahl & Way, 2006). Between-person designs have limitations when trying to understand directionality between constructs over time (Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, 2015). In order to fully dissect longitudinal relations among two constructs, analytic models must disaggregate within- and between-person changes in each construct, and then focus on how within-person changes in one construct relate to within-person change in the other (Curran & Bauer, 2011; Hamaker, et al., 2015). This analytic approach is particularly important in testing theoretical models linking ERI and discrimination. For instance, the PVEST model emphasizes the importance of self-appraisal and individual responses to stress in linking discrimination to subsequent changes in ERI. Between-person analyses only capture changes relative to the overall sample (whether an individual is higher or lower as compared to others). However, within-person analyses examine whether an increase or decrease in an individual’s own experiences of discrimination, as compared to what an individual is used to experiencing, links to changes in ERI. Accordingly, the current study drew on a six-wave prospective longitudinal design to disaggregate within- and between-person relations between perceived discrimination and ERI components. First, we examined concurrent relations between perceived discrimination and ERI, focusing on the contemporaneous within-person relations between the two constructs. Next, we examined whether (a) within-person fluctuations in perceived discrimination predicted changes in adolescents’ ERI one year later, accounting for prior levels of ERI, and (b) the competing hypothesis, whether within-person fluctuations in ERI predicted changes in perceived discrimination one year later, accounting for prior levels of perceived discrimination. We also examined between-person relations between ERI and discrimination, which provided an average association between the two constructs across individuals and time. We controlled for adolescent nativity as differences in discrimination and ERI by nativity status have emerged in previous work (e.g., Edward & Romero, 2008). Further, we accounted for whether or not adolescent mothers were enrolled in school given that this context is particularly important for perceiving discrimination (Hughes, Watford, & Del Toro, 2016).

Method

Participants

The current analytic sample included 181 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers from a six-wave longitudinal study of 204 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers conducted from 2007 to 2013 (Umaña-Taylor, Guimond, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2013). The majority of adolescents participated across all six waves (i.e., 96% at W2, 85% (W3), 84% (W4), 85% (W5), and 84% at W6). Twenty-three adolescents were excluded from the study because they lived in Mexico or were residing in Mexico during at least one of the interview periods. Participants were interviewed each year; W1 occurred when the adolescent mother was in her third trimester of pregnancy and W2 to W6 occurred 10, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months postpartum. At W1, mothers were, on average, 16.83 years of age (SD = 1.01) and the majority were enrolled in school (61%). School enrollment declined across the five subsequent waves (42%, 30%, 23%, 14%, 11%, W2 – W6, respectively). A majority of adolescents were U.S. born (67%). Family income at W1 was $28,354 (SD = 20,496), on average, which was calculated as a sum of household income, additional funds contributed to the household by others, and public financial assistance (i.e., public assistance, food stamps).

Procedure

Data came from a convenience sample of a larger project that focused on the pregnancy and parenting experiences of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2013). Participants for the larger project were recruited from community agencies and high schools in a Southwestern metropolitan area. Eligibility criteria included that adolescents had to be of Mexican origin, 15 to 18 years of age, currently pregnant, and not legally married. Interviews were conducted in participants’ preferred language, and most adolescents participated in English at W1 (66%). Participants received $25 for participation at W1, $30 at W2, $35 at W3, $40 at W4, $50 at W5, and $60 at W6. All procedures were approved by the university’s Human Subjects Review Board.

Measures

Perceived discrimination

Adolescents’ responses to a revised version of the Perceived Discrimination Scale (PDS; Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001) were utilized to assess their perceived discrimination at W1–W6. The original PDS was designed for use with American Indian adolescents; the adapted version revised items to be applicable to Latinos (Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). The 10 items (e.g., “How often have others said something bad or insulting to you because you are Hispanic/Latina?”) were scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from Almost never (1) to Very often (4). Higher scores indicated higher perceived ethnic-racial discrimination. Cronbach’s alphas at W1–W6 ranged from .80 – .89.

Ethnic-racial identity

Adolescents’ responses on the 17-item Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez (2004) were used to assess the three dimensions of ERI at W1–W6: exploration (7 items; “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity”); resolution (4 items; “I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me”); and affirmation (6 items; “My feelings about my ethnicity are mostly negative”). Responses ranged from (1) Does not describe me at all to (4) Describes me very well, and negatively worded items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated higher ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Cronbach’s alphas at W1–W6 ranged from .77 – .86 for ERI exploration, .81 to .85 for ERI resolution, and .77 to .86 for ERI affirmation.

Covariates

Adolescents reported their nativity status (i.e., 0 = Mexico-born; 1 = U.S.-born) and their date of birth at Wave 1 (which was used to calculate age at each wave). They also indicated whether they were enrolled in school at each wave (0 = not enrolled in school; 1 = enrolled in school).

Results

Analytic Strategy

Multi-level modeling (MLM) in Mplus version 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014) was used to examine our research questions. Specifically, we estimated a two-level model with observations nested within individuals. For both discrimination and each component of ERI (i.e., exploration, resolution, affirmation), we first examined a growth model to estimate the overall pattern of change in each construct across the six waves of data. Next, we examined the concurrent associations for within- and between-person ERI components and discrimination. Given our interest in understanding the direction of effects between discrimination and components of ERI (i.e., exploration, resolution, affirmation), models were run in which the dependent variable was either discrimination or ERI (i.e., exploration, resolution, affirmation) at any given time point. Finally, we examined the lagged associations between discrimination and ERI to understand how within-person ERI components predicted subsequent changes (the next year) in discrimination (and how within-person changes in discrimination predicted subsequent changes in ERI components). Time-varying predictors were centered at each person’s mean to represent the within-person (WP) effect, and a cross-time average of predictors was computed and centered at the grand mean to represent the between-person (BP) effect. In all models, adolescent nativity, age, and school enrollment were included as controls. In the lagged analyses, prior levels of the dependent variable were included as controls.

Descriptive Information and Initial Analyses

Table 1 presents bivariate correlations and descriptive information for all variables. An initial model was estimated to examine the time trend in ERI exploration, resolution, affirmation, and discrimination. For ERI exploration, there was no significant growth (blinear = .01, SE = .01, p = .31). ERI resolution demonstrated significant linear growth across time (blinear =.04, SE =.01, p < .001). For ERI affirmation, there was initial linear growth (blinear = .04, SE = .01, p < .01) that slowed across time (bquadratic = −.01, SE = .008, p < .05). Finally, discrimination demonstrated a significant linear decline across time (blinear = −.02, SE = .01, p < .05). As a result, we included a linear time function as a covariate for resolution and discrimination, and a linear and quadratic time function as a covariate for affirmation.

Table 1.

Descriptives and Correlation for Study Variables (N = 181)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | 19. | 20 | 21. | 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Exp 1 | .52*** | .38*** | .34*** | .33*** | .33*** | .51*** | .29*** | .24** | .22** | .20* | .26** | .06 | −.02 | −.05 | −.10 | −.09 | −.06 | .05 | .19* | .16* | .05 | .09 | .10 | −.01 | −.08 | |

| 2. | Exp 2 | .46*** | .36*** | .46*** | .43*** | .38*** | .42*** | .31*** | .21* | .25** | .35*** | .06 | .12 | .02 | .05 | .14 | .07 | .02 | .15 | .04 | −.10 | .01 | −.01 | .06 | −.16* | ||

| 3. | Exp 3 | .46*** | .48*** | .51*** | .30*** | .26** | .48*** | .26** | .37*** | .41*** | .03 | −.01 | .08 | .04 | .00 | .04 | .09 | .09 | .09 | −.01 | .02 | .03 | −.07 | −.15 | |||

| 4. | Exp 4 | .56*** | .55*** | .19* | .13 | .15 | .53*** | .44*** | .39*** | −.02 | −.04 | −.05 | .02 | −.04 | −.04 | −.05 | .08 | .02 | .00 | −.10 | .01 | −.12 | −.09 | ||||

| 5. | Exp 5 | .61*** | .29*** | .33*** | .33*** | .37*** | .54*** | .42*** | .16* | .23** | .06 | .12 | .05 | .15 | .00 | .06 | .06 | −.10 | .03 | −.06 | −.12 | −.08 | |||||

| 6. | Exp 6 | .21** | .16 | .27** | .42*** | .46*** | .48*** | .02 | .07 | .03 | .12 | .04 | .11 | .08 | .06 | .08 | .03 | .03 | .06 | −.02 | −.11 | ||||||

| 7. | Res 1 | .51*** | .34*** | .27** | .30*** | .37*** | .14 | .17* | .09 | .00 | .02 | .11 | .04 | .10 | .08 | .06 | .00 | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | |||||||

| 8. | Res 2 | .27** | .28** | .36*** | .29*** | .24** | .26** | .16 | .15 | .22** | .17* | −.07 | .01 | .01 | −.14 | −.07 | −.09 | .01 | −.05 | ||||||||

| 9. | Res 3 | .21* | .34*** | .38*** | .12 | .18* | .25** | .09 | .12 | .12 | −.01 | .02 | .02 | .04 | −.03 | −.05 | .00 | −.07 | |||||||||

| 10. | Res 4 | .54*** | .45*** | .09 | .12 | .10 | .24** | .09 | .14 | −.04 | −.03 | −.08 | .00 | −.16 | −.10 | −.08 | −.05 | ||||||||||

| 11. | Res 5 | .57*** | .03 | .14 | .04 | .04 | .08 | .03 | −.04 | .03 | .10 | −.10 | −.05 | −.08 | −.08 | −.13 | |||||||||||

| 12. | Res 6 | .15 | .19* | .07 | .06 | .10 | .14 | .03 | .07 | .02 | −.08 | −.09 | −.08 | .03 | −.06 | ||||||||||||

| 13. | Aff 1 | .44*** | .32*** | .49*** | .62*** | .61*** | −.23** | −.15* | −.30*** | −.22** | −.32*** | −.03 | .10 | .12 | |||||||||||||

| 14. | Aff 2 | .43*** | .62*** | .54*** | .57*** | −.18* | −.10 | −.23** | −.18* | −.15 | −.13 | .10 | .18* | ||||||||||||||

| 15. | Aff 3 | .59*** | .66*** | .68*** | −.19* | −.33*** | −.28*** | −.21* | −.44*** | −.03 | −.02 | .13 | |||||||||||||||

| 16. | Aff 4 | .75*** | .81*** | −.31*** | −.37*** | −.45*** | −.33*** | −.43*** | .02 | −.01 | .07 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17. | Aff 5 | .75*** | −.27** | −.29*** | −.34*** | −.29** | −.34*** | .03 | −.01 | .10 | |||||||||||||||||

| 18. | Aff 6 | −.37*** | −.36*** | −.50*** | −.42*** | −.44*** | −.03 | .00 | .08 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 19. | Disc 1 | .52*** | .61*** | .53*** | .53*** | .21* | .07 | .17* | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20. | Disc 2 | .59*** | .50*** | .52*** | .32*** | .07 | .20** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. | Disc 3 | .61*** | .71*** | .43*** | .11 | .00 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. | Disc 4 | .69*** | .41*** | −.03 | .12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. | Disc 5 | .45*** | .10 | .08 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24. | Disc 6 | .14 | .07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. | Age 1 | .06 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. | Nat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | 2.88 | 2.87 | 2.90 | 2.94 | 2.93 | 2.94 | 3.30 | 3.39 | 3.53 | 3.47 | 3.51 | 3.57 | 3.81 | 3.82 | 3.86 | 3.89 | 3.90 | 3.88 | 1.35 | 1.34 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.23 | 16.83 | .67 | |

| SD | .71 | .66 | .65 | .71 | .65 | .71 | .71 | .64 | .60 | .65 | .59 | .56 | .47 | .41 | .44 | .32 | .33 | .39 | .37 | .42 | .45 | .45 | .46 | .34 | 1.01 | .47 | |

Note: Exp = ERI Exploration, Res = ERI Resolution, Aff = ERI Affirmation, Disc = Perceived Discrimination. Nat = Nativity. Numbers after variable names indicate wave. Nativity is coded 0 = Mexico-born, 1 = U.S. born.

p < .05.

p < .01

p < .001

Concurrent Associations between ERI and Discrimination

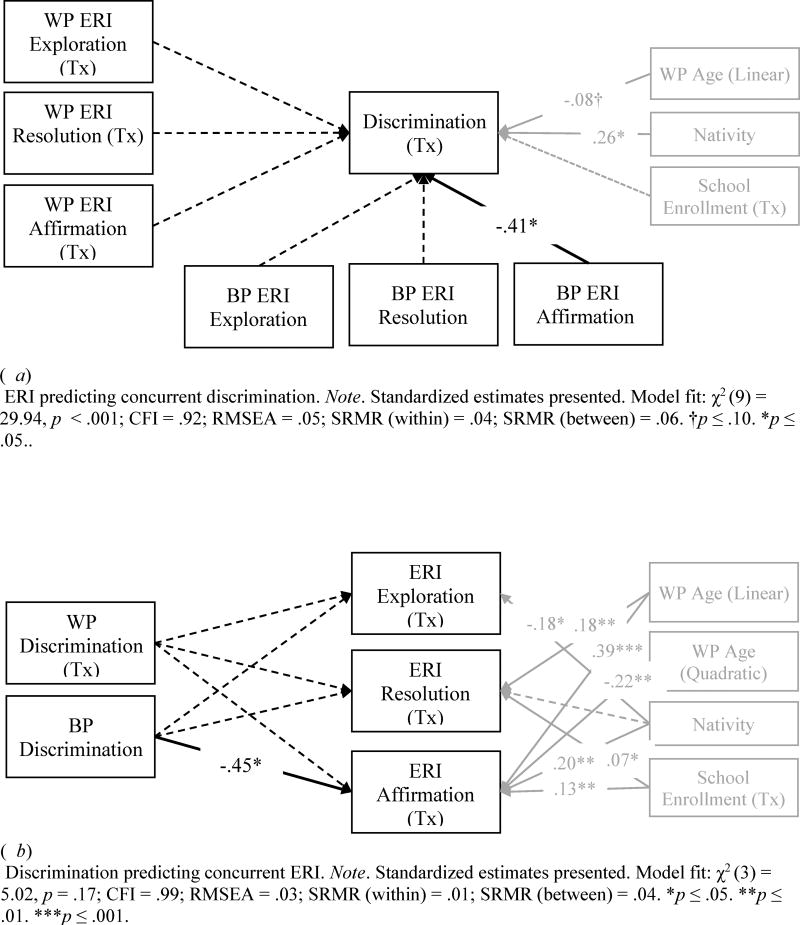

Next, we examined how within-person (WP) fluctuations in ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation related to concurrent discrimination, controlling for adolescent age, nativity, school enrollment, and developmental changes in discrimination based on age (Figure 1a). In the same model, we also examined the between-person (BP) effects of ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation on discrimination. Significant covariates indicated that perceptions of discrimination decreased over the course of the study (marginally significant), and that U.S.-born adolescents reported higher levels of discrimination than Mexico-born adolescents. With respect to the effects of interest, results revealed no relation between WP ERI components and discrimination. A significant BP affirmation effect emerged, indicating that individuals who reported greater ERI affirmation (compared to the overall sample average), tended to report lower levels of discrimination.

Figure 1.

Contemporaneous relations between ERI and Discrimination (1a) and Discrimination and ERI (1b). Solid lines indicate significant effects; dashed lines indicated non-significant effects. Control variables are presented within grey boxes and their estimated effects are illustrated with grey lines.

Next, we examined a similar model, but with ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation serving as the dependent variable, and discrimination as the predictor (Figure 1b). There were a number of significant covariates. As expected based on the initial growth models, there was a significant linear increase in ERI resolution, and an initial increase that slowed across time for ERI affirmation. Additionally, U.S.-born adolescents reported lower ERI exploration and higher ERI affirmation than Mexico-born adolescents. With respect to the effects of interest, results revealed that WP discrimination was not a significant predictor of ERI exploration, resolution, or affirmation. BP discrimination predicted ERI affirmation; individuals who reported greater discrimination (as compared to the overall sample), also reported lower levels of affirmation.

Lagged Association between ERI and Discrimination

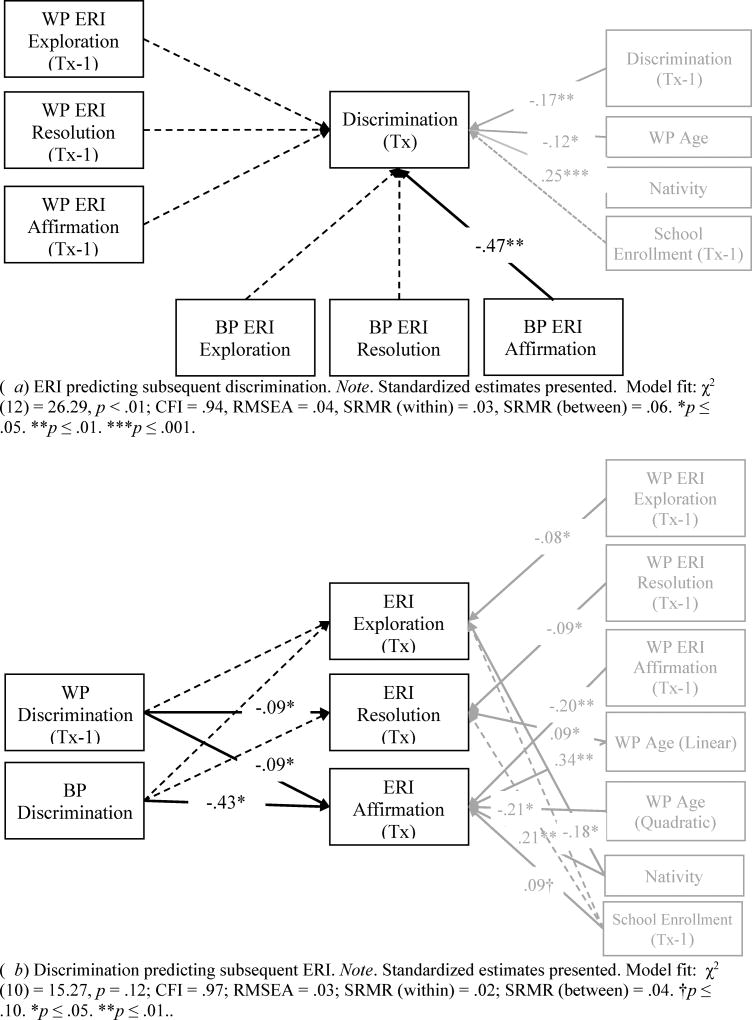

Next, we examined how prior WP fluctuations (t −1) in ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation predicted discrimination (t) experiences one year later, controlling for adolescent age, nativity, school enrollment, and prior levels of discrimination (t −1). WP fluctuations in ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation did not significantly predict subsequent discrimination (Figure 2a). Similar to the concurrent analyses, BP ERI affirmation was negatively related to discrimination.

Figure 2.

Lagged relations between ERI and Discrimination (2a) and Discrimination and ERI (2b). Solid lines indicate significant effects; dashed lines indicated non-significant effects. Control variables are presented within grey boxes and their estimated effects are illustrated with grey lines.

Then, we examined a similar model, but with ERI exploration, resolution, and affirmation serving as the dependent variables, and prior WP fluctuations in discrimination (t − 1) as the predictor (Figure 2b). Results revealed a significant WP discrimination effect on ERI resolution and affirmation, suggesting that increases in discrimination within an individual predicted decreases in ERI resolution and affirmation one year later, controlling for adolescent age, nativity, school enrollment and prior levels of ERI resolution and affirmation. A significant BP effect of discrimination on ERI affirmation also emerged, suggesting that individuals who reported greater levels of discrimination than the average level across the sample, tended to report lower levels of ERI affirmation.

Discussion

The current study examined the concurrent and longitudinal prospective associations between perceived discrimination and ERI components (i.e., exploration, resolution, and affirmation) among a sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. The study offers a number of innovations for the field. First, we examined the bidirectional nature of this interrelation by testing models in which perceived discrimination predicted ERI, and in which ERI predicted perceived discrimination. Consideration of these alternative models is rarely undertaken in the same study, but is necessary to rule out competing hypotheses about directionality. Second, we combined between- and within-person perspectives to provide greater conceptual clarity about the degree to which the interrelation of perceived discrimination and ERI produced changes within adolescents over time. Overall, our findings are in line with theoretical models (i.e., PVEST, rejection-identification) that point to the importance of discrimination experiences in predicting subsequent changes in identity. Specifically, we found that perceptions of discrimination predicted changes in Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ ERI, but that ERI did not predict changes in adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination. Identifying the directionality of this association is critical to our understanding of the ways that youth navigate both the identity process and their experiences of discrimination during adolescence and has the potential to inform future prevention efforts.

Perceived Discrimination and ERI Exploration

Our results indicated that the degree to which Mexican-origin adolescents had explored their ethnic-racial background at any given point in time in the study was unrelated to their concurrent and subsequent perceptions of discrimination. Thus, perceptions of discrimination appear to be neither a catalyzing (Cross, 1995), nor inhibiting (Major & Schmader, 1998) experience when it comes to the ERI exploration process. This null finding is consistent with Umaña-Taylor and Guimond (2010), who found that perceived discrimination was unrelated to both initial levels and subsequent growth in exploration for Latina adolescents. It is also consistent with findings among Black and Latino high school students (both boys and girls)—Black adolescents reported an association between discrimination and exploration, but Latino adolescents did not (Pahl & Way, 2006). However, it should be stressed that our sample only considered girls and given prior research suggesting that discrimination experiences are particularly impactful on boys (Alfaro, Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, Bámaca, & Zeiders, 2009), a continued focus and examination on Mexican-origin boys is needed. For girls, one possible explanation for the null findings is that they may have other salient experiences at play that inform their engagement in ERI exploration. For example, research has shown that adolescents’ ERI exploration is related to the cultural socialization messages they receive from their families (Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, Knight, Roosa, Berkel, & Nair, 2014), and that this relation is particularly strong among females (Juang & Syed, 2010), and may be especially salient among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers who are relying heavily on their own mothers for support during early parenthood (Contreras, Narang, Ikhlas, & Teichman, 2002).

Perceived Discrimination and ERI Resolution

As for ERI resolution, no concurrent relations emerged between within-person effects of ERI resolution and perceived discrimination. However, in the lagged analyses, findings suggested within-person effects such that when Mexican-origin adolescent mothers experienced increases in perceived discrimination (relative to their own average experiences), they reported decreases in clarity about the personal meaning of their ERI one year later. As for the competing model, ERI resolution did not predict subsequent perceptions of discrimination. Generally, these findings support theoretical notions from the PVEST theory and the rejection-identification model, both of which point to the importance of discrimination experiences in shaping subsequent identity. However, the negative association is somewhat surprising given that the rejection-identification model, in particular, argues that discrimination may bring a greater awareness and sense of identity (resulting in greater resolution). In light of this, our findings may be more in line with Cross’s (1995) explanation that being confronted with negative messages about yourself as a function of your ethnic/racial group can serve as an “encounter” experience that spurs a reconsideration of one’s identity. Note however, that Fuller-Rowell and colleagues (2013) found that the association between discrimination and resolution differed based on American identity; those with the strongest American identities reported a negative association, whereas those with a weaker American identities reported a positive association. The current study did not assess American identity, but such findings suggest that future research should consider the potential interactions between ERI and other aspects of identity.

Perceived Discrimination and ERI Affirmation

Finally, no concurrent relations emerged between within-person effects of affirmation and discrimination. However, in the lagged analyses, findings suggested that when Mexican-origin adolescent mothers experienced increases in perceived discrimination (relative to their own average experiences), they reported decreases in ERI affirmation one year later. These findings are consistent with some previous empirical work indicating that adolescents’ positive sense of self suffers in the face of perceived discrimination (e.g., Hou et al., 2015; Seaton et al., 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010), but inconsistent with one study that reported no association between within-person changes in discrimination and Latino and African American adolescents’ affirmation (Pahl & Way, 2006). Further, findings are somewhat inconsistent with theoretical models that emphasize that discrimination may evoke coping resources (PVEST) and a greater awareness of self (rejection-identification model). Again, these findings may align more with the explanation that discrimination experiences are negative “encounter experiences” that subsequently make you feel less positive about your ethnic-racial background. For adolescent mothers in particular, this unique period—a time in which they are navigating parenthood and normative developmental challenges—may make them particularly sensitive to internalizing the underlying messages of discrimination to the extent that they felt less positively about their ethnic-racial group membership (e.g., Crocker & Major, 1989). Null findings in previous studies may be tied to contextual and developmental differences. For instance, Pahl and Way’s (2006) sample came from a predominantly minority school context; in such a setting, certain protective factors may be at play that could have buffered the negative effect of discrimination on ERI affirmation that emerged in the current and other previous studies.

In addition to this within-person effect, a between-person effect also emerged; adolescents who, on average, perceived greater discrimination over time had lower levels of ERI affirmation. Perceptions of discrimination may be a catalyst that produces within-person decreases in ERI affirmation that solidify over time; adolescents who consistently perceive high levels of discrimination may develop persistently low affirmation.

Contributions, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current study examined the interrelations between ERI and discrimination among Mexican-origin adolescent females. We tested competing hypotheses (which have rarely been considered) to move the field forward in understanding how a developmentally normative process of ERI coincides with the relatively normative experiences of discrimination for Latina youth. Further, we utilized longitudinal data to examine within-person changes in each construct. This analytic approach aligns with theoretical models linking discrimination to ERI and is a robust way of testing change, as it focuses on understanding changes within individuals, ruling out the influence of stable confounds. Further, the lagged within-person longitudinal design provided a rigorous test of the direction of effects by looking at how within-person change predicts subsequent changes in individuals’ behaviors (Singer & Willet, 2003). Aside from a repeated measures experimental design, the current study’s design is one of the strongest tests of causation and direction of effects of two constructs using non-experimental techniques in the naturalistic setting (Singer & Willet, 2003). Our findings suggest that perceived discrimination informs the development of ERI, rather than the development of ERI informing youths’ perceptions of discrimination.

Despite the study’s contributions, there are limitations worth noting. First, the population under study was limited to a community-based sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Although this group is critical to examine due to high rates of teenage pregnancy (Martin et al., 2012) and the fact that ethnic-racial aspects of identity become salient during the transition to parenthood (Hughes et al., 2006), results have limited generalizability (e.g., not generalizable to males or to Latina adolescents from other national origin groups). Understanding the directionality between discrimination and ERI is needed in other samples with equal representation of male and female youth across different developmental periods, as the process of ERI development and individuals’ exposure to discrimination differs by adolescent gender (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010) and the uniqueness of adolescent mothers’ experiences does not map on directly to other youths’ developmental experiences. It could be that dynamic relations between ERI and discrimination differ based on developmental periods—for younger youth, the new relations between discrimination and ERI could be much stronger given the new found cognitive awareness of discrimination (Brown & Bigler, 2005) and the emphasis on identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Although we found that ERI did not predict discrimination, an association for younger youth may be evident as identity processes may shape the way in which they start to notice discriminatory experiences. Future research examining the directionality of ERI and discrimination across early adolescence is needed. A second limitation worth noting is the reliance on self-report for all study variables. Self-reports can inflate the observed associations and are prone to issues of shared method variance. Future studies with multi-informant methods could provide a stronger test of the relations observed in our study.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides one of the first six-year longitudinal examinations of the bidirectional nature of ERI and discrimination. From a practical standpoint, these findings underscore the importance of discrimination experiences in developmental processes of adolescent mothers. Many studies have demonstrated that ERI can buffer the negative effects of discrimination on numerous indices of adolescent adjustment (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003; Umaña-Taylor, Tynes, Toomey, Williams, & Mitchell, 2015). Thus, our finding that discrimination can undermine adolescents’ ERI development is troubling because it implies that the very resource that can potentially protect youth against the deleterious effects of discrimination is threatened by the risk factor it can protect against. Specific to adolescent mothers, this may mean that prevention programs, which typically focus on supporting adolescent mothers’ parenting processes (e.g., Easterbrooks, Kotake, Raskin, & Bumganer, 2016; Jacobs et al., 2016), should also consider adolescent mothers’ experiences that are not solely tied to their parenting status. Growing evidence suggests that parents’ discrimination experiences impact parent-child interactions and children’s developmental outcomes (Zeiders, Umaña-Taylor, Jahromi, Updegraff, & White, 2016). Thus, practitioners and family members should be aware that experiences of discrimination can pose significant risks to adolescent mothers, their ERI development, their parenting, and ultimately their young children’s development. Therefore, implementing interventions focused on strengthening adolescents’ ERI (see Umaña-Taylor, Douglass, Updegraff, & Marsiglia, 2017, for an example) are necessary and may counteract the negative effects of discrimination. Given that discrimination remains a salient experience for ethnic-racial minority youth in the U.S. (Umaña-Taylor, 2016), and that ERI is an important developmental competency that can promote positive development among marginalized youth (Williams et al., 2012), identifying ways to intervene in this dimension of youths’ experiences will be critical for promoting positive outcomes among ethnic-racial minority youth, particularly adolescent mothers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061376; PI: Umaña-Taylor), the Department of Health and Human Services (APRPA006011; PI: Umaña-Taylor), and the Cowden Fund and Challenged Child Project of the T. Denny School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. We thank the adolescents and female family members who participated in this study. We also thank Edna Alfaro, Mayra Bámaca, Diamond Bravo, Emily Cansler, Lluliana Flores, Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Elizabeth Harvey, Melissa Herzog, Sarah Killoren, Ethelyn Lara, Esther Ontiveros, Jacqueline Pflieger, Alicia Godinez and the undergraduate research assistants of the Supporting MAMI project for their contributions to the larger study.

References

- Alfaro EC, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Bámaca MY, Zeiders KH. Latino adolescents' academic success: The role of discrimination, academic motivation, and gender. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(4):941–962. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski JG, Bisconti T, Week D, Willard C, Koegh DA, Whitman TL. The adolescent as parent: Influences on children’s intellectual, academic and socioemotional 0 development. In: Borkowski JG, Ramey SL, Bristol-Power M, editors. Parenting and the Child’s World: Influences on Academic, Intellectual, and Social-Emotional Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Bigler RS. Children's perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development. 2005;76(3):533–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Narang D, Ikhlas M, Teichman J. A conceptual model of the determinants of parenting among Latina adolescent mothers. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the U.S. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96(4):608–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr . The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the Cross model. In: Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995. pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal LW, Holt VL. Young maternal age and depressive symptoms: results from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:266–270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Kotake C, Raskin M, Bumgamer E. Patterns of depression among adolescent mothers: Resilience related to father support and home visiting programs. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:61–68. doi: 10.1037/ort0000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward LM, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Ong AD, Phinney JS. National identity and perceived discrimination predict changes in ethnic identity commitment: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Latino college students. Applied Psychology. 2013;62(3):406–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, García HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman RPPP. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods. 2015;20(1):102–116. doi: 10.1037/a0038889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Kim SY, Wang Y, Shen Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Longitudinal reciprocal relationships between discrimination and ethnic affect or depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(11):2110–2121. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0300-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DL, Watford JA, Del Toro A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic-racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. Advances in Child Development and Behaviors. 2016;51:1–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs F, Easterbrooks MA, Goldberg J, Mistry J, Bumgarner E, Raskin M, et al. Improving adolescent parenting: Results from a randomized controlled trial of home visiting program for young families. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:342–349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang L, Syed M. Family cultural socialization practices and ethnic identity in college-going emerging adults. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Schmader T. Coping with stigma through psychological disengagement. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The Target’s Perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Marks AK, Ejesi K, McCullough MB, García Coll C. Developmental implications of discrimination. In: Lamb ME, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. Volume 3: Socioemotional Processes. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishers; 2015. pp. 324–365. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ Division of Vital Statistics. Births: Final data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Report. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_09.pdf.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s guide (Version 7.31) Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Children's developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1998;7:27–45. doi: 10.1016/s0962-1849(98)80020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33(11):2288–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01885.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, Sellers RM. A longitudinal examination of racial identity and racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2009;80:406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Morgan L, Brown TN. A multidimensional approach to racial identity: Implications for African American children. In: Neal-Barnett AM, Contreras JM, Kerns KA, editors. Forging Links: African American Children, Clinical Developmental Perspectives. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2001. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SA, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Old issues and new theorizing about African-American youth: A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory. In: Taylor RL, editor. Black Youth: Perspectives on their Status in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 1995. pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartmann T. A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9(4):817–833. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. 6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishers; 2006. pp. 829–893. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DP, Spencer MB, Harpalani V, Spencer TR. Identity processes and the positive youth development of African Americans: An explanatory framework. New Directions for Youth Development. 2002;95:73–100. doi: 10.1002/yd.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ. A post-racial society in which ethnic-racial discrimination still exists and has significant consequences for youths’ adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2016;25:111–118. doi: 10.1177/0963721415627858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Douglass S, Updegraff KA, Marsiglia F. Small-scale randomized efficacy trial of the Identity Project: Promoting adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12755. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Guimond AB. A longitudinal examination of parenting behaviors and perceived discrimination predicting Latino adolescents' ethnic identity. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(3):636–650. doi: 10.1037/a0019376. doi: http:10.1037/2168-1678.1.S.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Guimond AB, Updegraff KA, Jahromi LB. A longitudinal examination of support, self-esteem, and Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ parenting efficacy. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75:746–759. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, O’Donnell M, Knight GP, Roosa MW, Berkel C, Nair R. Mexican-Origin early adolescents’ ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and psychosocial functioning. The Counseling Psychologist. 2014;42:170–200. doi: 10.1037/a0029438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Seaton E. Ethnic and Racial Identity Revisited: An Integrated Conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Tynes B, Toomey RB, Williams D, Mitchell K. Latino adolescents’ perceived discrimination in online and off-line settings: An examination of cultural risk and protective factors. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:87–100. doi: 10.1037/a0038432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(4):549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4(1):9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, Stubben JD. Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:405–424. doi: 10.2307/3090187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Tolan PH, Durkee MI, Francois AG, Anderson RE. Integrating racial and ethnic identity research into developmental understanding of adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):304–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Jahromi LB, Updegraff KA, White RMB. Discrimination and acculturation stress: A longitudinal study of children’s well-being from prenatal development to 5 years of age. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2016;37:557–564. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]