Abstract

Beta-casein (BC) in cow’s milk occurs in several genetic variants, where BC A1 (BCA1) and BC A2 (BCA2) are the most frequent. This work deals with a method based on modified polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using urea PAGE to discriminate BCA1 and BCA2 variants from Holstein Friesian (HF) and genetically selected Jersey A2/A2 (JA2) cow’s milk. Two well defined bands were obtained from BC fraction of HF milk, while that of JA2 showed a single band. Proteins from these bands were sequenced by HPLC-quadrupole linear ion trap/mass spectrometry, resulting in BCA1 and BCA2 separation from the BC fraction of HF milk, whereas BCA2 was the only constituent of JA2 fraction. This method represents a feasible and useful tool to on site phenotyping of BC fraction of cow’s milk for pharmaceutical and food industries applications.

Keywords: Cow’s milk, Beta casein A1, Beta casein A2, Polyacrylamide gel, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

Beta casein (BC) is a hydrophobic globular protein consisting of a single polypeptide chain composed of 209 amino acid residues and molecular mass of about 24 kDa (Atamer et al. 2017; Huppertz 2013). Its net charge at pH 6.6 is about − 11.5, due to a 21 negatively charged residues located at N-terminal polar domain and a large hydrophobic C-terminal domain (Huppertz 2013). These properties are used to separate it from other caseins in cow’s milk by electrophoretic mobility (Kiddy 1975; Thompson et al. 1969).

The most frequent genetic variants of BC in milk from the majority of dairy cattle in Western nations are BC A1 (BCA1) and BC A2 (BCA2) (Kaminski et al. 2007). These two genetic variants differ only by one amino acid, His-67 for BCA1 and Pro-67 for BCA2 (Raies et al. 2015). The positively charged imidazole side chain of His-67 in BCA1 results in net charge reduction compared to BCA2 (Eigel et al. 1984), allowing the separation of these genetic variants by electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels. Additionally, gastrointestinal digestion of BCA1 releases the seven-amino acid peptide beta casomorphin 7 (BCM7), comprising Tyr-60 to Ile-66 residues (Jinsmaa and Yoshikawa 1999); whereas Pro-67 in BCA2 makes BCM7 release less likely (Cieslinska et al. 2012).

From epidemiological studies, consumption of milk containing BCA1 and the consequent release of BCM7 after gastrointestinal digestion, have been considered as potential health risk factors. Incidence of human ischemic heart disease, atherosclerosis, type 1 diabetes, food allergies, chronic constipation, autism, schizophrenia and sudden infant death syndrome have been attributed to BCA1 and BCM7 peptide (Kaminski et al. 2007; Sadler and Smith 2013).

Therefore, for companies claiming to offer BCA1-free milk there is a great interest in developing rapid and reliable analytical methods to test the BC phenotype in raw cow’s milk. BC fractions can be analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under acidic and alkaline conditions (Grosclaude et al. 1972; Huppertz 2013), and isoelectric focusing (Bulgari et al. 2013; Caroli et al. 2016). The PAGE method reported here was modified from Andrews (1983), and employs a sample buffer without sucrose and about twice urea concentration for better resolution. In addition, urea was increased to 9 M in the resolving gel buffer, while the acrylamide concentration of this gel was increased to 15%. Furthermore, sucrose was not added to the stacking gel, and separation was conducted at lower temperature (4 °C). More sophisticated methods include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Bonizzi et al. 2009), HPLC coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS) (Givens et al. 2013; Nguyen et al. 2015), and capillary zone electrophoresis (De Noni 2008). However, these methods require robust equipment and are more time consuming than PAGE so they are not considered practical for industrial scale routine analysis of BC genetic variants.

The objectives of this work were to use a modified alkaline urea PAGE method to separate the most common BC fractions from raw cow’s milk and to confirm the identity of the separated BCA1 and BCA2 through amino acid sequencing using high resolution equipment.

Materials and methods

Materials

Bovine BC standard, dithiotreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IAA), and thermolysin (Type X), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tris base, EDTA disodium salt, ammonium persulfate, TEMED, and Coomassie G-250 were acquired from Bio-Rad (molecular biology grade; Hercules, CA, USA). Urea, 2-mercaptoethanol, glycine, bisacrylamide, bromophenol blue, absolute ethanol and glacial acetic acid were purchased from Avantor (Center Valley, PA, USA). DNA extraction and purification were performed using the Invitrogen PureLink® DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR-amplification created restriction site (ACRS-PCR) was carried out utilizing Platinum™ Hot Start PCR Master Mix from Invitrogen (Thermo). Protein concentration was determined with the Qubit® Protein Assay Kit (Invitrogen).

Collection of milk samples

Individual samples of raw bovine milk were collected from naive Holstein Friesian (HF) breed (n = 40, pooled into 2 milk samples of 600 mL). Samples were also taken from previously genotyped A2/A2 Jersey (JA2) breed (n = 40, pooled into 4 milk samples of 300 mL each, for easier handling and processing due to higher fat content than HF cow’s milk). Cattle were housed in dairy herds located at Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, Mexico. Raw milk samples were stored at − 20 °C until analysis. Jersey cows’ genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood samples by salt-ethanol extraction and silica-based spin column purification according to Invitrogen’s PureLink® DNA Mini Kit, and genotyping for the CSN2 A2 allele was performed by ACRS-PCR, according to Raies et al. (2012).

Whole casein fractionation

Whole casein fractionation was carried out by a modified isoelectric precipitation method according to Hollar et al. (1991). Briefly, pooled raw milk samples were mixed at 60 °C, and fat separated by centrifugation at 2600×g for 20 min at room temperature. Then, skimmed milk pH was adjusted to 4.6 using 10% (v/v) acetic acid. After isoelectric precipitation, samples were centrifuged, and the resultant supernatants were decanted. Whole casein pellets were washed twice in acidic distilled water (pH 4) followed by centrifugation. Whole casein pellets were resuspended in distilled water and pH adjusted to 7.5. Protein concentration was determined using the Qubit® Protein Assay kit and the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher) as recommended by the manufacturer.

BCA1 and BCA2 genetic variants discrimination by modified alkaline urea PAGE

PAGE of bovine casein was performed according to Andrews (1983) with modifications. Briefly, casein samples were mixed 6:1 (v/v) with a 0.12 M Tris base, 0.0025 M EDTA, 8.2 M urea, 0.2 M 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.01% bromophenol blue 6x sample loading buffer. Casein working solutions were heat denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, then 7.9 µg and 6.1 µg of casein protein derived from HF and JA2 cow’s milk, respectively, were loaded into PAGE wells. The stacking gel solution was prepared to 4% acrylamide, whereas the resolving gel contained 15% acrylamide, 9 M urea at pH 8.9. A Mini PROTEAN cell (Bio-Rad) filled with 0.02 M Tris, 0.19 M Glycine, pH 8.3 running buffer was used. Separation was performed at 4 °C, 0.01 A for 15 min, followed by 0.03 A for 2 h. The gel was stained with Coomassie G-250 and documented on a GelDoc EZ system (Bio-Rad), using the ImageLab 5.2.1 software (Bio-Rad).

BCA1 and BCA2 genetic variants identification by HPLC–MS amino acid sequencing

After alkaline urea PAGE, BCA1 and BCA2 bands were excised from the gel, reduced with 10 mM DTT, alkylated with 55 mM IAA, and digested overnight with thermolysin (1:30 enzyme:protein ratio) at 75 °C. The resulting peptides were reconstituted in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile with 1% acetic acid (v/v) to a final amount of about 500 pmol. Sample was directly applied at a flow rate of 300 nL/min into a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) using an EASY-nLC II nanoflux pump delivery system. The peptides were separated in a house made capillary column (0.75 µm internal diameter × 10 cm long, RP-C18) using a linear gradient of 10–80% solvent B (water/acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid) in solvent A (deionized water). Mass spectrometry system was set on a xyz multi-axis translational stage to optimize the electrospray ionization (ESI) signal. Collision induced dissociation and high-energy collision dissociation modes were applied, selecting 1+ and 2+ charges. All spectra were obtained in the positive ion mode. Fragmentation data collection was performed with an isolation width of 3.0 (m/z), normalized collision energy of 3 5 arbitrary units, a Q activation of 0.250, activation time of 10 ms and maximum injection time of 10 ms. Data collection was performed with Proteome Discoverer™ Software (Thermo Fisher).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and mean ± standard error was reported.

Results and discussion

Casein fractions extracted from HF and JA2 cow’s raw milk samples were separated into BC and alpha casein (Fig. 1, lanes 3–8), where alpha casein showed a higher mean relative mobility (Rf = 0.553 ± 0.003) compared to BC (mean Rf = 0.219 ± 0.002). BCA2 has been detected in at least 10 different casein genotypes samples, with mean Rf = 0.220 ± 0.001, relative standard deviation = 0.41%, with a detection limit of 6 µg. These results are consistent with other reports (Andrews 1983; Aschaffenburg and Thymann 1965; Peterson and Kopfler 1966). According to Kiddy (1975), PAGE is more suitable than either paper or starch gel for BC genetic variants identification, and successfully separated A, B, C, D and E variants of BC. At pH 8.6, alpha casein is more negatively charged than BC, so that relative mobility is alpha casein > BC (Swaisgood 1992).

Fig. 1.

Representative illustration of electrophoretic separation of whole casein fraction from cow’s milk by modified urea PAGE. Whole casein fraction was resolved in a 15% polyacrylamide gel under reducing, denaturing and alkaline conditions. Lanes 1–2. Bovine beta casein standard (Sigma Aldrich); lanes 3–4. Whole casein fraction obtained from naïve Holstein Friesian cow’s milk; lanes 5–8. Whole casein fraction obtained from CSN2 A2/A2 genotyped Jersey cow’s milk. Whole casein fraction from cow´s milk separated under conditions described above resulted in alpha casein being more negatively charged compared to beta casein. Bovine beta casein standard was used as reference to identify beta casein fraction in whole casein from cow´s milk. Furthermore, beta casein fraction from Holstein Friesian cow’s milk was separated into two bands, band 1 (Bd 1) and band 2 (Bd 2), corresponding to beta casein A1 and A2, respectively. In contrast, CSN2 A2/A2 genotyped Jersey beta casein fraction generated only one single band corresponding to beta casein A2. Protein band identity from cow´s milk beta casein fraction was determined by HPLC-LTQ-MS

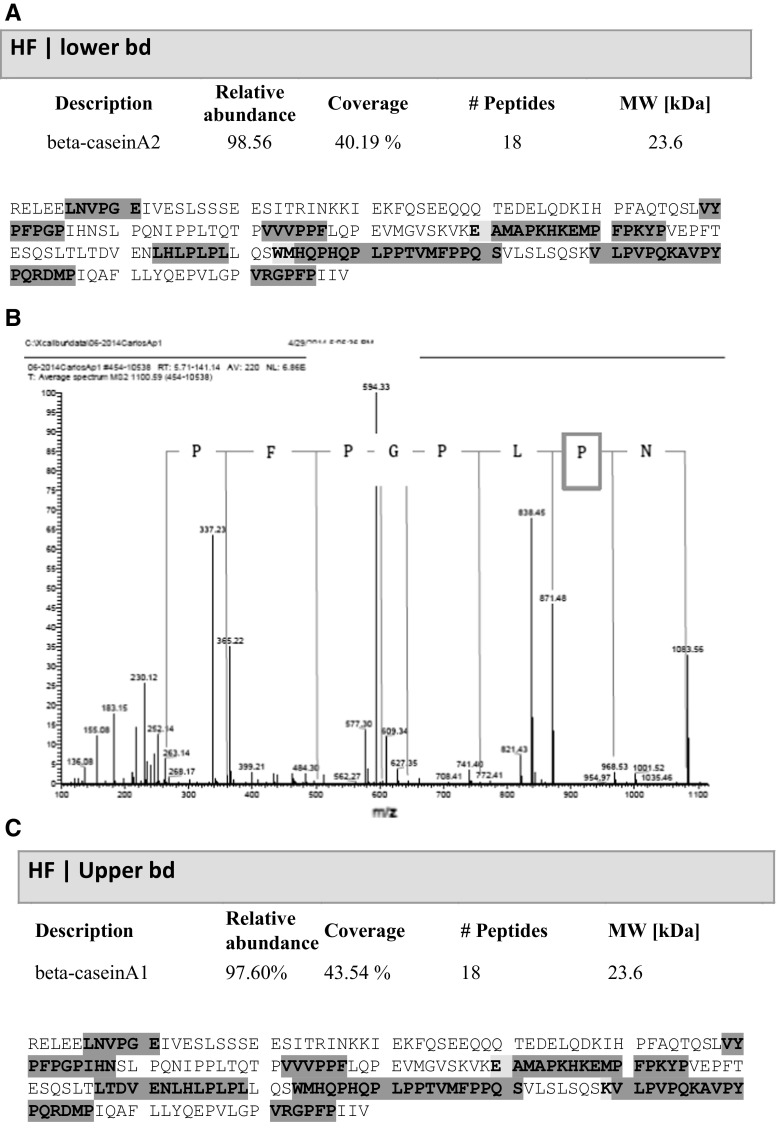

Resolution of the BC fraction from HF cow’s milk casein resulted in two bands (Fig. 1; lanes 3 and 4, bands 1 and 2). Band 1 showed mean Rf = 0.203 ± 0.005 while band 2 revealed Rf = 0.217 ± 0.005. In contrast, BC fraction in caseins from JA2 cow’s milk presented only one band with mean Rf = 0.220 ± 0.001 (Fig. 1, lanes 5–8). Bands were consistently found in all triplicate experiments. The amino acid sequence and mass spectra of HF casein is shown in Fig. 2. Upper and lower bands refer to the separation achieved from SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). The amino acid sequence of HF lower band (BCA2) is shown in Fig. 2a, while the corresponding mass spectrum is observed in Fig. 2b; here proline is highlighted by a blue square. Figure 2c shows the amino acid sequence of HF upper band, corresponding to band 1 of Fig. 1 in the HF BC fraction, which coincided with BCA1 as reported in NCBI data base (Fig. 3). Band 2 and the unique band from JA2 milk were homologous to the BCA2 sequence according to UniProt KB data base (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Representative illustration of amino acid sequencing of cow’s milk beta casein fraction by HPLC–MS. a Full amino acid sequence of protein band Bd 2 (lower band) of Holstein Friesian (HF) beta casein fraction. b Manual analysis of mass spectra obtained from protein band Bd 2 (lower band) of Holstein Friesian (HF) beta casein fraction. Proline residue at position 67 is highlighted by a blue square. c Full amino acid sequence of protein band Bd 1 (Upper band) of Holstein Friesian (HF) beta casein fraction

Fig. 3.

Amino acid sequence alignment of both BCA1 and BCA2 using the Similarity Alignment Tool for protein sequences from ExPASy-Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Complete amino acid sequence of BCA1 (GenBank ID: AAA30431.1) and BCA2 (UniProtKB ID: P02666) mature proteins were deduced comparing data obtained from HPLC–MS analysis with protein sequences databases from the NCBI using the protein BLAST tool. The rectangle depicts the change of histidine (H) residue in BCA1 to proline (P) residue in BCA2

Aschaffenburg and Thymann (1965) as well as Peterson and Kopfler (1966) separated cow’s milk BC genetic variants by PAGE under alkaline followed by acidic conditions. However, the method reported here can separate them using one step only. According to Veloso et al. (2004) electrophoretic separation shows better resolution than HPLC for casein proteolysis. Nevertheless, these authors were not able to separate BCA1 from the whole casein fraction. The significance of the presence of BCA2 arises from its reported correlation with improved production traits, milk composition and quality (Nilsen et al. 2009).

Cow’s milk BC is coded by the CSN2 gene mapped on bovine chromosome 6q31 (Gene ID: 281099, NCBI database). Single nucleotide polymorphism 201-CCT-203 (GenBank: JX273429.1) to 201-CAT-203 (GenBank: JX273430.1) in exon 7 of bovine CSN2 gene results in the substitution of Pro-67 in BCA2 to His-67 in BCA1, respectively (Caroli et al. 2009; Gallinat et al. 2013). The reported average frequency of CSN2 A2:A1 allele distribution in Holstein Friesian breed, which is the most common dairy breed in Mexico, is 0.40:0.60, respectively (Martin et al. 2013). In contrast, Jersey herds typically have an average frequency of CSN2 A2 allele distribution of 0.70 (Kaminski et al. 2007).

Due to health and economic impact related to the composition of BC fraction of cow’s milk proteins, different robust analytical methods have been developed with suitable resolution to determine the BC phenotype. However, the majority of these methods require specialized equipment that may represent a great technical challenge for dairy breeders.

The electrophoretic method reported here is capable of discriminating between BCA2 and BCA1 in the casein fraction of raw cow’s milk without performing more elaborate phenotyping approaches. This method represents a feasible and selective tool with suitable resolution to analyze the phenotype of cow’s milk BC fraction in the production unit. For industrial applications analytical proof is required to claim that milk contains BCA2 fraction only.

Conclusion

The urea PAGE under alkaline conditions methodology described in this work can be used to determine the phenotype of BC in cow’s milk by directly analyzing whole casein milk fraction. The method’s resolution performance showed good reliability on bulk milk samples drawn from production farm and on site sampling. A significant operational advantage can be achieved as high cost specialized equipment methods can be replaced by a simple procedure. In addition, this protocol can be easily adopted in the control of industrial processes as common instrumentation is only needed. Resolution and reliability of this modified urea PAGE method can be applied by dairy producers, and control services as an on-line tool for milk production quality assurance.

Acknowledgements

Tanks are given to CONACyT-PEI, for Grant No. C003V-2013-01-199586. Authors acknowledge Ecológico Tierra Viva breeders for genotyping control data and provision of milk samples. Authors thank Dr. C. Ferreira-Batista and E. Meneses-Romero from IBT, UNAM, México for technical support in BC sequencing.

References

- Andrews AT. Proteinases in normal bovine milk and their action on caseins. J Dairy Res. 1983;50:45–55. doi: 10.1017/S0022029900032519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschaffenburg R, Thymann M. Simultaneous phenotyping procedure for the principal proteins of cow’s milk. J Dairy Sci. 1965;48:1524–1526. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(65)88511-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atamer Z, Post AE, Schubert T, Holder A, Boom RM, Hinrichs J. Bovine β-casein: isolation, properties and functionality. A review. Int Dairy J. 2017;66:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2016.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzi I, Buffoni JN, Feligini M. Quantification of bovine casein fractions by direct chromatographic analysis of milk. Approaching the application to a real production context. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgari O, Raineri M, Gigliotti C, Caroli AM. Metodo per la quantificazione delle varianti genetiche di β-caseina bovina. Scienza Tecnica Lattiero-Casearia. 2013;64:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Caroli AM, Chessa S, Erhardt GJ. Milk protein polymorphisms in cattle: effect on animal breeding and human nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:5335–5352. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroli AM, Savino S, Bulgari O, Monti E. Detecting β-casein variation in bovine milk. Molecules. 2016;21:141–147. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslinska A, Kostyra EB, Kostyra H, Olenski K, Fiedorowicz E, Kaminski SA. Milk from cows of different β-casein genotypes as a source of β-casomorphin-7. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63:426–430. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.634785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Noni I. Release of β-casomorphins 5 and 7 during simulated gastrointestinal digestion of bovine β-casein variants and milk-based infant formulas. Food Chem. 2008;110:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigel WN, Butler JE, Emstrom EA, Farrell KM, Harwalkar VR, Jenness R, Whitney RML. Nomenclature of proteins of cow’s milk: fifth revision. J Dairy Sci. 1984;67:1599–1631. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81485-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallinat JL, Qanbari S, Drogemuller C, Pimentel ECG, Thaller G, Tetens J. DNA-based identification of novel bovine casein gene variants. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96:699–709. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens I, Aikman P, Gibson T, Brown R. Proportions of A1, A2, B and C β-casein protein variants in retail milk in the UK. Food Chem. 2013;139:549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosclaude F, Mahe MF, Mercier JC, Ribadeau-Dumas B. Caracterisation des variants genetiques des caseine αs1 et β bovines. Eur J Biochem. 1972;26:328–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollar CM, Law AJ, Dalgleish DG, Medrano JF, Brown RJ. Separation of beta-casein A1, A2, and B using cation-exchange fast protein liquid chromatography. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3308–3313. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz T. Chemistry of the caseins. In: Fox PF, editor. Advanced dairy chemistry. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jinsmaa Y, Yoshikawa M. Enzymatic release of neocasomorphin and beta-casomorphin from bovine beta-casein. Peptides. 1999;20:957–962. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(99)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski S, Cieslinska A, Kostyra E. Polymorphism of bovine beta-casein and its potential effect on human health. J Appl Genet. 2007;48:189–198. doi: 10.1007/BF03195213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiddy CA. Gel electrophoresis in vertical polyacrylamide beds. Procedure II. In: Swaisgood HE, editor. Methods of gel electrophoresis of milk proteins. American Dairy Science Association: Illinois; 1975. pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bianchi L, Cebo C, Miranda G. Genetic polymorphism of milk proteins. In: Fox PF, editor. Advanced dairy chemistry. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 463–514. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DD, Busetti F, Johnson SK, Solah VA. Identification and quantification of native beta-casomorphins in Australian milk by LC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS. J Food Compos Anal. 2015;44:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2015.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen H, Olsen HG, Hayes B, Sehested E, Svendsen M, Nome T, Meuwissen T, Lien S. Casein haplotypes and their association with milk production traits in Norwegian Red cattle. Genet Sel Evol. 2009;41:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-41-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RF, Kopfler FC. Detection of new types of b-casein by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at acid pH: a proposed nomenclature. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1966;22:388–392. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(66)90658-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raies MH, Kapila R, Shandilya UK, Dang AK, Kapila S. Detection of A1 and A2 genetic variants of β-casein in Indian crossbred cattle by PCR-ACRS. Milchwissenschaft. 2012;67:396–398. [Google Scholar]

- Raies MH, Kapila R, Kapila S. Release of β-casomorphin-7/5 during simulated gastrointestinal digestion of milk β-casein variants from Indian crossbred cattle (Karan Fries) Food Chem. 2015;168:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler MJ, Smith N. Beta-casein proteins and infant growth and development. Infant J. 2013;9:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Swaisgood HE. Chemistry of the caseins. In: Fox PC, editor. Advanced dairy chemistry. London: Elsevier Applied Science; 1992. pp. 63–110. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Gordon WG, Boswell RT, Farrell HM. Solubility, solvation and stabilization of αs1- and β-caseins. J Dairy Sci. 1969;52:1166–1173. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(69)86719-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veloso ACA, Teixeira N, Peres AM, Mendonça A, Ferreira IMPLVO. Evaluation of cheese authenticity and proteolysis by HPLC and urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Food Chem. 2004;87:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.12.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]