Abstract

Cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) has been recognized as one of cisplatin’s serious side effects, limiting its use in cancer therapy. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and SIRT3 play protective roles against cisplatin-induced kidney injury. However, the role of SIRT7 in cisplatin-induced kidney injury is not yet known. In this study, we found that Sirt7 knockout (KO) mice were resistant to cisplatin-induced AKI. Furthermore, our studies identified that loss of SIRT7 decreases the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by regulating the nuclear expression of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B. It has been reported that cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity is mediated by TNF-α. Our results indicate that SIRT7 plays an important role in cisplatin-induced AKI and suggest the possibility of SIRT7 as a novel therapeutic target for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity.

Introduction

Cisplatin is a highly effective anti-cancer agent used in the treatment of solid organ tumors, such as head and neck, lung, breast, testis, and ovarian cancers1,2. Although cisplatin has taken a leading role in cancer therapy, its use is limited by its nephrotoxicity. Cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) has been recognized as one of its serious side effects1–3.

Sirtuins (SIRTs) are a family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent histone deacetylases that regulate a variety of biological processes, including metabolism, inflammation, DNA repair, and aging4. Seven SIRTs (SIRT1–7) have been identified in mammals, and these proteins display different intracellular localization, enzymatic activity, and biological functions5. Previous studies have shown that the kidney-specific overexpression of SIRT1 or SIRT1 activation by resveratrol ameliorates cisplatin-induced AKI6,7. In addition, Sirt3-deficient mice given cisplatin experience more severe AKI than wild-type (WT) mice8. These findings indicate that both SIRT1 and SIRT3 play protective roles against cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Meanwhile, SIRT7 is an NAD+-dependent deacetylase with high selectivity for acetylated lysine 18 of histone H3 (H3K18), which plays a role in maintaining the transformed state of cancer cells by repressing the transcription of tumor suppressor genes9. We reported that Sirt7 knockout (KO) mice are resistant to high-fat diet-induced body weight gain, fatty liver, and glucose intolerance10. Other studies have also shown the important biological functions of SIRT7 in different tissues11–15. However, the role of SIRT7 in cisplatin-induced kidney injury is not known.

In this study, we investigated the role of SIRT7 in renal injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity using Sirt7 KO mice. We found that Sirt7 KO mice showed protective effects against cisplatin-induced AKI. Furthermore, our studies also identified that the loss of SIRT7 decreases the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a critical proinflammatory cytokine in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, by regulating the nuclear expression of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). Our results indicate that SIRT7 plays an important role in cisplatin-induced AKI.

Results

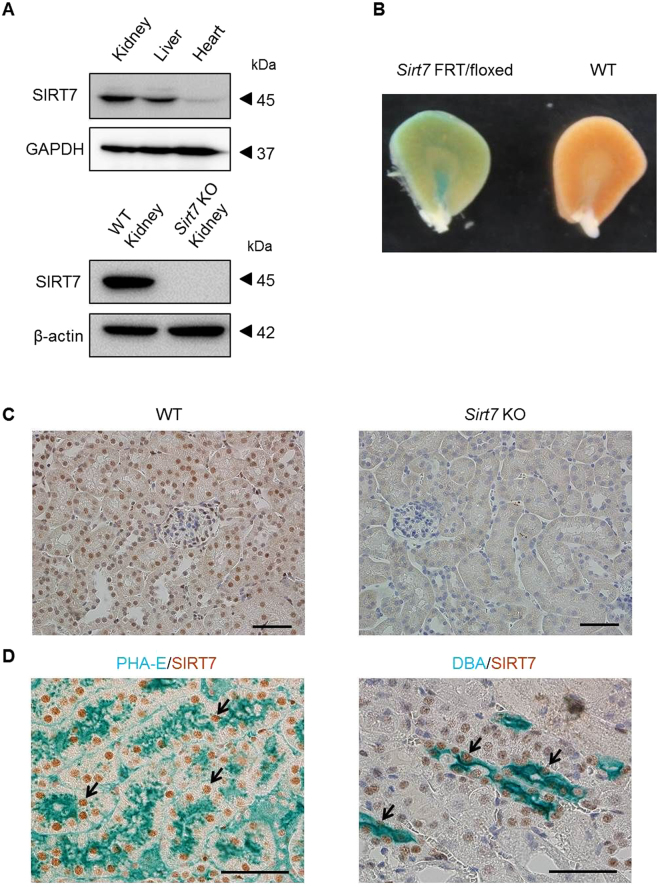

Expression of SIRT7 in the Kidney

SIRT7 is ubiquitously expressed in mouse tissues11. Consistent with these findings, SIRT7 protein expression was detected in the mouse kidney (Fig. 1A). The expression of Sirt1–6 mRNA was unchanged in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The expression pattern of SIRT7 in the kidney was assessed with Sirt7 FRT/floxed mutant mice, which contain the LacZ gene under the control of the Sirt7 promoter10. The inner medullary region and cortical region of the kidney were positive for X-gal staining (Fig. 1B). Parallel immunohistochemical analysis was performed using an anti-SIRT7 antibody. SIRT7 was expressed in the nuclei of renal tubular epithelial cells and glomeruli of the kidney of WT mice, but not in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 1C). Double immunostaining for SIRT7 and Phaseolus vulgaris erythroagglutinin (PHA-E) lectin (a marker of proximal tubular epithelial cells) revealed that SIRT7 is expressed in proximal tubular cells (Fig. 1D)16. Consistent with LacZ staining in the inner medullary region, SIRT7 was also expressed in Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA; a marker of collecting duct cells)-positive collecting duct cells (Fig. 1D)16. SIRT7 expression in proximal tubular cells was comparable with that in collecting duct cells (Supplementary Fig. S1B,C). No overt histological abnormalities were detected in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 1C). Moreover, there were no significant differences in body weight, urine volume, and serum components between the 8-week-old WT and Sirt7 KO mice (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of SIRT7 in the kidney. (A) SIRT7 expression in mouse kidney, liver, and heart was evaluated. GAPDH and β-actin were used as loading controls. SIRT7 protein expression was deleted in Sirt7 KO mouse kidney. (B) SIRT7 expression in the kidney of Sirt7 FRT/floxed mutant mouse was evaluated by β-galactosidase staining. (C) Representative photomicrographs (×400) of immunohistochemical staining for SIRT7 in kidney sections. Scale bar: 50 µm. (D) Representative photomicrographs (×400) of double immunostaining (lectin and SIRT7). PHA-E was used as a marker of proximal tubules and DBA was used as a marker of collecting tubules. The arrows indicate SIRT7-expressing nuclei. Scale bars: 50 µm.

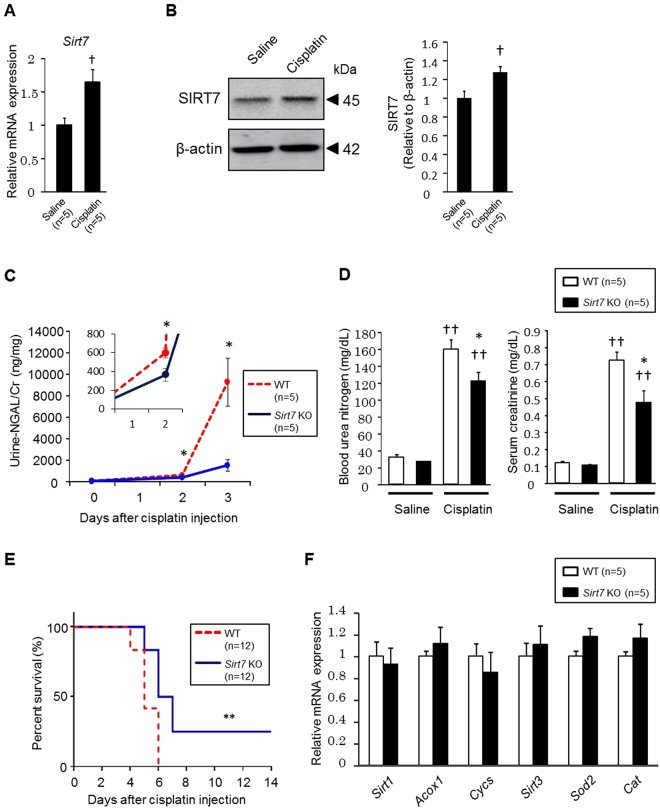

Cisplatin-induced Kidney Injury is Ameliorated in Sirt7 KO Mice

We investigated the role of SIRT7 in cisplatin-induced AKI. Cisplatin administration led to an increase of Sirt7 mRNA and SIRT7 protein expression in WT mice (Fig. 2A,B). We next studied the impact of SIRT7 deficiency on cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Interestingly, urinary levels of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), a biomarker of kidney injury17, were significantly lower in Sirt7 KO mice than in WT mice (Fig. 2C). Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels were significantly lower in Sirt7 KO mice than in WT mice at 72 h after cisplatin injection (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, Sirt7 KO mice showed a significantly higher survival rate than WT mice after cisplatin injection (Fig. 2E). These results indicated that Sirt7 KO mice were resistant to cisplatin-induced AKI. SIRT1 and SIRT3 play protective roles in the development of cisplatin-induced AKI6–8. However, the expression of Sirt1 and Sirt3 and their downstream target genes (SIRT1: acyl-CoA oxidase 1 [Acox1] and cytochrome c [Cycs]; SIRT3: superoxide dismutase 2 [Sod2] and catalase [Cat])6,18,19 was unchanged in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice after cisplatin administration (Fig. 2F), suggesting that the protective effect of SIRT7 deficiency is independent of these SIRTs.

Figure 2.

Deletion of SIRT7 ameliorates cisplatin-induced kidney injury. (A) Sirt7 mRNA expression in the kidney of WT mice was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5/group). (B) SIRT7 protein expression in the kidney of WT mice was evaluated. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 5/group). (C) Urine was collected for 24 h using metabolic cages, and urinary NGAL/creatinine levels were determined at each time point (n = 5/group). (D) Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels were measured at day 3 in the normal saline administration groups and cisplatin administration groups (n = 5/group). (E) Survival rate after cisplatin administration was assessed until day 14 (n = 12/group). (F) mRNA expression of Sirt1, Sirt3, and their target genes in the cisplatin-treated kidney of WT and Sirt7 KO mice was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5/group). *WT vs. Sirt7 KO, p < 0.05; **WT vs. Sirt7 KO, p < 0.01; †saline vs. cisplatin, p < 0.05; ††saline vs. cisplatin, p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

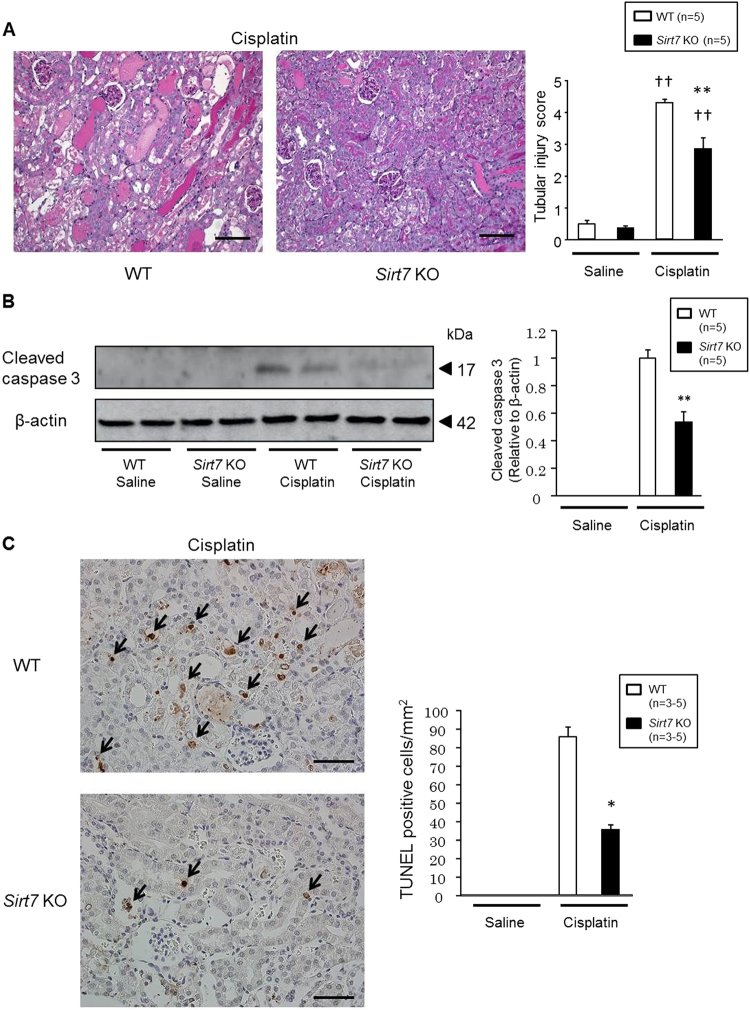

Cisplatin mainly affects the proximal tubules in the kidney1. Accordingly, histological analysis revealed that cisplatin treatment resulted in severe tubular injury reflected by necrosis, cast formation, dilation, and loss of the brush border in the cortical region of WT mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the cisplatin-induced damage was significantly ameliorated in the cortical region of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 3A). Neither WT nor Sirt7 KO mice showed kidney tissue injury in the inner medullary region by cisplatin (Supplementary Fig. S2). Cisplatin-induced activated (cleaved) caspase 3 protein expression was detected in the kidney of WT mice, but its expression was lower in Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 3B). Consistent with this result, the number of TUNEL-positive cells in the injured tubules was significantly decreased in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice, suggesting that loss of SIRT7 suppresses the apoptosis induced by cisplatin (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Deletion of SIRT7 ameliorates apoptosis in cisplatin-induced kidney injury. (A) Representative photomicrographs (×200) of PAS-stained kidney sections. The tubular injury score was calculated on a scale of 0–5 (n = 5/group). Scale bars: 100 µm. (B) Protein expression of cleaved caspase 3 in the kidney was evaluated by western blot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. (n = 5/group). (C) Representative photomicrographs (×400) of TUNEL staining in kidney sections. TUNEL-positive cells were counted in 4 randomly selected fields per section (n = 3/saline group, n = 5/cisplatin group). The arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bars: 50 µm. *WT vs. Sirt7 KO, p < 0.05; **WT vs. Sirt7 KO, p < 0.01; †saline vs. cisplatin, p < 0.05; ††saline vs. cisplatin, p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

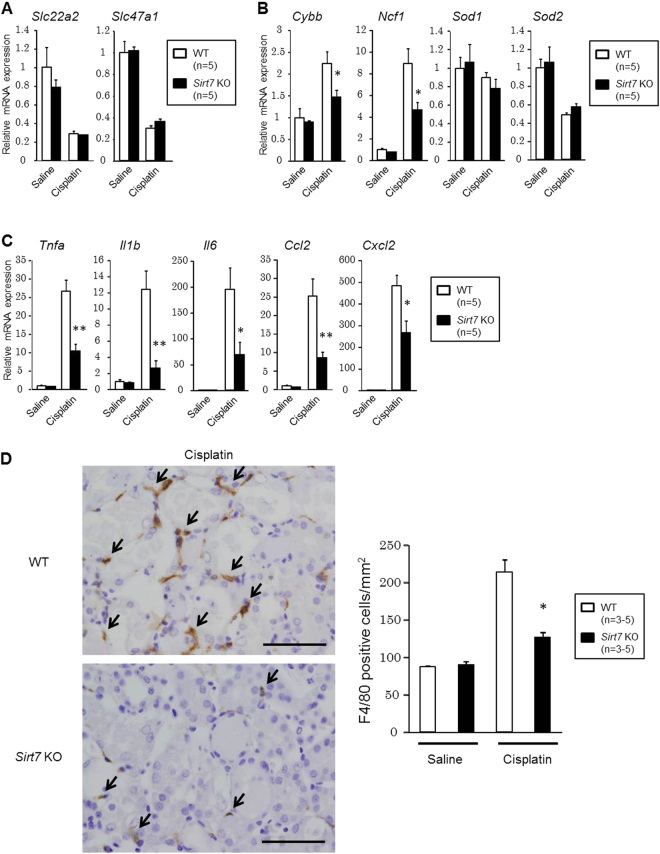

Inflammation-related Gene Expression and Macrophage Infiltration are Suppressed in the Kidney of Sirt7 KO Mice

Next, we analyzed the expression of genes involved in cisplatin-induced renal injury. The expression of the gene encoding OCT2 (Slc22a2), which plays a role in cisplatin uptake20, and MATE1 (Slc47a1), which regulates the excretion of cisplatin21, was unchanged (Fig. 4A). Oxidative stress and inflammation play important roles in the pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced kidney injury;1–3 therefore, we evaluated oxidative stress and inflammation-related gene expression. The expression of the genes encoding NOX2 (Cybb) and p47phox (Ncf1), which are involved in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), was significantly decreased in the cisplatin-treated kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 4B). The expression of genes involved in inflammation (Tnfa, Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, and Cxcl2) was also significantly reduced in the cisplatin-treated kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 4C), suggesting that SIRT7 plays critical roles in the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation.

Figure 4.

Suppression of the inflammatory response in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice. (A) Slc22a2 and Slc47a1 mRNA expression in mouse kidneys was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5/group). (B) Oxidative stress-related mRNA expression in mouse kidneys was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5/group). (C) Inflammation-related mRNA expression in mouse kidneys was determined by real-time PCR (n = 5/group). (D) Representative photomicrographs (×400) of immunostaining for F4/80 in kidney sections. F4/80-positive cells were counted in 4 randomly selected fields per section (n = 3/saline group, n = 5/cisplatin group). The arrows indicate F4/80-positive cells. Scale bars: 50 µm. The abundance of each mRNA type was normalized using GAPDH. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) is another experimental model of renal injury22. Consistent with the cisplatin model, the expression levels of Tnfa, Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, and Cxcl2 at an acute stage were significantly decreased in the obstructed kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S3).

In cisplatin nephropathy, the production of cytokines and chemokines by renal parenchymal cells leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells1. In accordance with the reduced expression of Ccl2 (encoding MCP1) (Fig. 4C), immunostaining for MCP1 showed a decrease of intensity in the cisplatin-treated kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S4). The number of F4/80-positive infiltrating macrophages in the interstitium was significantly suppressed in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice as compared with that in WT mice (Fig. 4D).

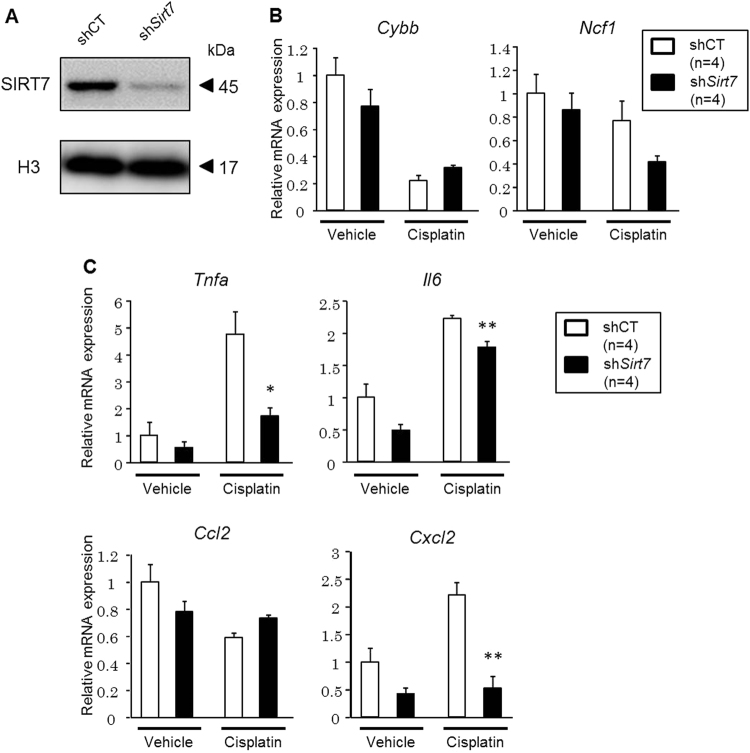

SIRT7 Regulates the Expression of TNF-α

We next examined gene expression in control and Sirt7 knockdown (KD) rat renal proximal tubular NRK-52E cells. The introduction of Sirt7 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) markedly reduced the levels of endogenous SIRT7 (Fig. 5A). The expression of Cybb, Ncf1, and Ccl2 mRNA was reduced in the cisplatin-treated kidney of Sirt7 KO mice (Fig. 4B,C), but their expression was not decreased in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells after cisplatin exposure (Fig. 5B,C). In contrast, the expression of Tnfa, Il6, and Cxcl2 (encoding MIP-2α) mRNA was significantly decreased in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells following cisplatin administration (Fig. 5C). The expression of Il1b mRNA in the cisplatin-treated cells was below the detection limit. These findings suggest that SIRT7 regulates the cisplatin-induced gene expression of Tnfa, Il6, and Cxcl2 via a cell-autonomous mechanism. Cisplatin treatment significantly induced TNF-α protein production in control NRK-52E cells, but resulted in no increase of TNF-α protein production in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells (Supplementary Fig. S5). TNF-α plays a critical role in renal injury and the increase of MIP-2α expression after cisplatin administration23,24, whereas it has been reported that IL-6 does not play an injurious role in cisplatin-induced AKI25. These results suggest that SIRT7 controls cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, at least partly by regulating the expression of TNF-α.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of Sirt7 decreases the expression of TNF-α in cisplatin-treated NRK-52E cells. (A) SIRT7 protein expression in shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells was evaluated by western blot analysis. (B) Oxidative stress-related mRNA expression in shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells was determined by real-time PCR (n = 4/group). (C) Inflammation-related mRNA expression in shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells was determined by real-time PCR (n = 4/group). The abundance of each mRNA type was normalized using GAPDH. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

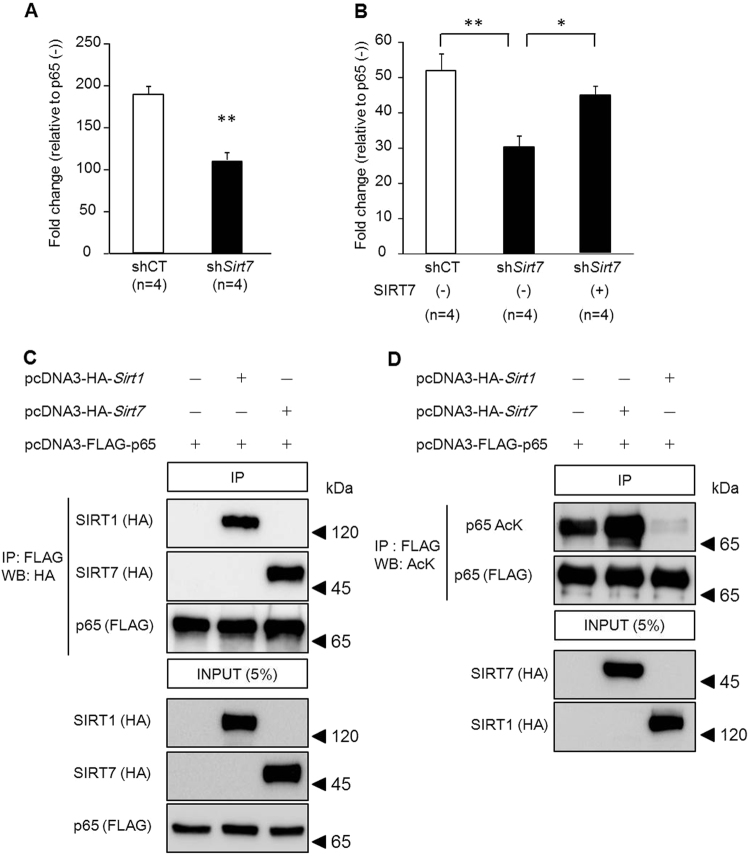

SIRT7 Regulates the Inflammatory Response Through Modulating NF-κB p65 Transcription Activity and Nuclear Translocation

The NF-κB transcription factor, composed of a heterodimer of p50 and p65 subunits, is a key mediator of the inflammatory response, including TNF-α, IL-6, and MIP-2α production26–29. In non-stimulated cells, NF-κB largely resides in the cytoplasm where it is bound by its inhibitory IκB family proteins. After stimulation, IκB proteins are phosphorylated by IκB kinase and degraded by the ubiquitin proteasome system30,31. Degradation of IκB proteins liberates NF-κB, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus. SIRT1, 2, and 6 regulate the function of NF-κB by interacting with p6532–34. Thus, we examined the effect of SIRT7 on NF-κB activity. Control and Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells were transfected with a p65 expression plasmid together with a pNF-κB luciferase reporter gene. Transfection of p65 activated the reporter gene by 188.9-fold in control NRK-52E cells. However, the transactivation activity of p65 in Sirt7 KD cells was significantly decreased by 41.6% (p < 0.01) (Fig. 6A). Overexpression of SIRT7 in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells restored the transactivation of NF-κB activity (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that NF-κB activity is reduced in SIRT7-deficient NRK-52E cells. Previous studies have revealed that FAF1, NME1, SNIP1, ING4, NFκBIL1, and TNFAIP1 regulate the activity of NF-κB in various ways35–41. Since SIRT7 is reported to bind to the proximal promoter regions of these genes9, SIRT7 might increase NF-κB activity by affecting their gene expression. However, the expression levels of these genes were similar between control and Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 6.

Regulation of the transactivation activity of NF-κB by SIRT7. (A,B) The transcriptional activity of NF-κB was examined using the dual luciferase reporter assay. Each Sirt7 KD (shSirt7) and control (shCT) NRK-52E cell was transfected with 80 ng pCI-HA-p65 expression plasmid or pCI-HA-control plasmid as well as 20 ng pNF-κB-Luc plasmid, which contains multiple copies of the NF-κB consensus sequence, and 0.8 ng pRL-TK plasmid (n = 4/group). In addition, Sirt7 KD cells were co-transfected with 100 ng pcDNA3-FLAG-Sirt7 expression plasmid or pcDNA3-FLAG-control plasmid (B) (n = 4/group). (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with 2 μg pcDNA3-HA-Sirt1 expression plasmid or pcDNA3-HA-Sirt7 expression plasmid as well as 2 μg pcDNA3-FLAG-p65 expression plasmid. At 24 h after transfection, an immunoprecipitation assay and western blotting were performed. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 μg pcDNA3-HA-Sirt1 expression plasmid or pcDNA3-HA-Sirt7 expression plasmid as well as 0.5 μg pcDNA3-FLAG-p65 expression plasmid and 0.5 μg pCMVβ-p300-myc expression plasmid. After 36 h, an immunoprecipitation assay was performed and p65 acetylation was detected by western blotting. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

SIRT1 regulates the activity of NF-κB through the deacetylation of p65. We then examined whether SIRT7 can also deacetylate p65. A co-immunoprecipitation assay revealed that SIRT7 as well as SIRT1 bound to p65 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 6C). Deacetylation of p65 by SIRT1 was detected in these cells (Fig. 6D, lane 3) as described previously32, while SIRT7 overexpression did not decrease the acetylation status of p65 (Fig. 6D, lane 2). These results indicate that SIRT7 has no deacetylase activity for p65.

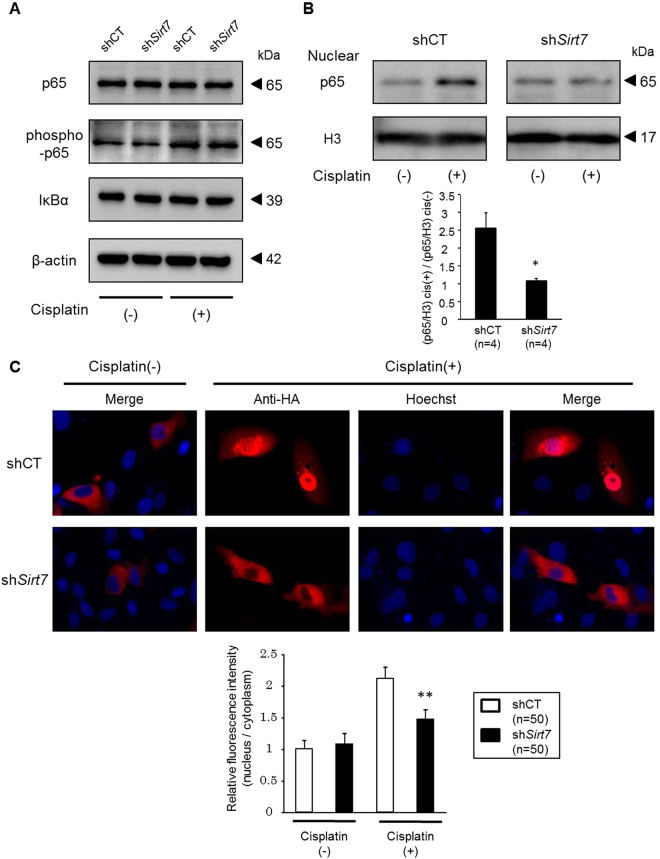

Western blot analysis revealed that the expression levels of p65, phospho-p65, and IκBα proteins in whole cell lysates were unchanged between the control and Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells (Fig. 7A). We next investigated nuclear p65 expression after cisplatin treatment. Exposure of the control NRK-52E cells to cisplatin markedly increased the levels of nuclear p65, whereas this increase was significantly blunted in the Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells (Fig. 7B). The suppression of increased nuclear p65 expression by cisplatin was also detected in Sirt7 KO mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (Supplementary Fig. S7). We next examined the effect of SIRT7 on the cellular location of p65 by immunofluorescence microscopy. Transiently transfected p65 was mainly cytoplasmic in both untreated control and Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells (Fig. 7C). After cisplatin stimulation, p65 staining was detected in the nucleus of the control cells, but p65 signals mostly remained cytoplasmic after cisplatin exposure in the Sirt7 KD cells (Fig. 7C). Relative nuclear p65 fluorescence intensity was significantly decreased in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells.

Figure 7.

Nuclear accumulation of p65 is suppressed in Sirt7-deficient cells. (A) Protein expression of p65, phospho-p65, and IκBα in whole cell lysates of shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells with or without 1-h cisplatin (30 μM) treatment was evaluated by western blot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Protein expression of p65 in the nuclear fraction with or without 1-h cisplatin (30 μM) treatment. Relative nuclear p65 expression was normalized by H3 (p65/H3, n = 4/group). To indicate the fold change of nuclear p65 expression by cisplatin, the value of p65/H3 with cisplatin exposure (p65/H3 cis (+)) was divided by that without cisplatin (p65/H3) cis (−)) (n = 4/group). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure S7. (C) Intracellular localization of p65. NRK-52E cells with or without 1-h cisplatin (30 μM) treatment were transfected with the pCI-HA-p65 plasmid, and p65 expression was evaluated by HA immunostaining. For nuclear staining, Hoechst 33342 was used. Relative fluorescence intensity is represented by the ratio of nuclear fluorescence intensity in the ROI to cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity in the ROI as measured by ImageJ software (n = 50/group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

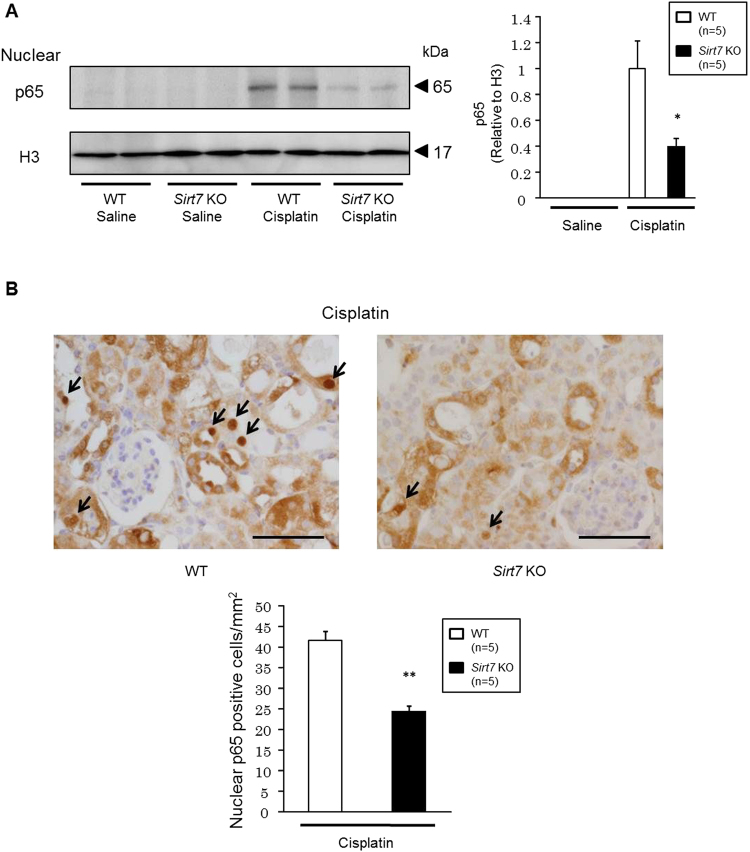

Finally, we examined nuclear p65 protein expression in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice. Western blotting analysis revealed that nuclear p65 protein expression was significantly decreased in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice compared with that in WT mice after cisplatin administration (Fig. 8A). Immunohistochemical analysis also showed that the number of nuclear p65-positive tubular cells was significantly decreased in the Sirt7 KO mice compared with that in the WT mice (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that the loss of SIRT7 suppresses the nuclear accumulation of p65 after cisplatin exposure both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 8.

Nuclear accumulation of p65 is suppressed in the kidney of cisplatin-treated Sirt7 KO mice. (A) Protein expression of p65 in the nuclear fraction of mouse kidney was evaluated by western blot analysis. H3 was used as a loading control (n = 5/group) (B) Nuclear p65 protein expression in tubular cells was evaluated by p65 immunostaining (n = 5/group). The arrows indicate p65-expressing nuclei. Scale bars: 50 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Inflammation and ROS-generated oxidative stress are involved in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity1–3. Previous studies have indicated that SIRT1 and SIRT3 are protective in cisplatin-induced kidney injury6–8. Interestingly, SIRT7 apparently plays an opposite role. TNF-α plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of cisplatin-induced AKI23,24 and stimulates the expression of a number of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g., MIP-2α). NADPH oxidase is a significant source of ROS. TNF-α also enhances ROS production by increasing the expression of NOX2 and p47phox, which are subunits of the NADPH oxidase complex42,43. The expression of Tnfa, Cxcl2 (encoding MIP-2α), Cybb (encoding NOX2), and Ncf1 (encoding p47phox) mRNA was significantly reduced in the cisplatin-treated kidney of Sirt7 KO mice. Thus, SIRT7 deficiency might ameliorate cisplatin-induced renal injury at least in part by reducing the expression of TNF-α. SIRT2 deficiency ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute tubular injury and suppresses renal failure with decreased renal Cxcl2 mRNA expression44. Thus, the reduced expression of Cxcl2 might also be involved in the amelioration of cisplatin-induced kidney injury.

Inflammation is one of the key processes that contributes to renal injury at an acute stage in the UUO model22. The expression levels of Tnfa and Cxcl2 were significantly decreased in the obstructed kidney of Sirt7 KO mice. Decreased expression of inflammation-related genes is also detected in the heart of Sirt7 KO mice after myocardial infarction and in the white adipose tissue of high-fat diet-fed Sirt7 KO mice10,14. These findings strongly suggest that SIRT7 plays critical roles in the regulation of inflammation. In the present study, we identified that NF-κB activity and the expression of TNF-α are decreased in cisplatin-treated Sirt7 KD NRK-52E kidney cells. However, considering the important roles of macrophages in the progression of inflammation and the anti-inflammatory roles of SIRTs in macrophages45,46, further investigation is required to clarify the relative contribution of TNF-α production by SIRT7 in infiltrating immune cells using macrophage-specific Sirt7 KO mice.

SIRTs regulate NF-κB function in multiple ways. SIRT6 suppresses NF-κB target gene expression by deacetylating histone H3 lysine 9 and destabilizing the binding of NF-κB to chromatin34. Phosphorylation of p65 stimulates acetylation at Lys 310, and this acetylation enhances the transcriptional activity of NF-κB47. SIRT1 and SIRT2 inhibit NF-κB activity through deacetylation of p65 at Lys 31032,33. We found that total p65 expression levels were unchanged, but nuclear p65 expression after cisplatin exposure was decreased in Sirt7 KD NRK-52E cells. We also found that Sirt7 deficiency in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells led to the suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced p65 nuclear accumulation (unpublished data). Thus, SIRT7 may regulate the nuclear accumulation of NF-κB p65. SIRT7 is located in the nucleus, while p65 is predominantly present in the cytosol of unstimulated cells. However, there is substantial evidence indicating that NF-κB-IκBα complexes are not static in their localization but are shuttled continuously between the nucleus and cytoplasm48–50. It may not be unanticipated, therefore, that SIRT7 binds to p65 in the nucleus and regulates this shuttling. Although SIRT7 could not deacetylate p65, recent studies have shown that SIRT7 exhibits desuccinylase or defatty-acylase activity51,52. Therefore, SIRT7 might regulate nuclear p65 translocation by regulating non-acetyl-lysine modifications. Lysine acetylation affects protein-protein interactions53. Alternatively, SIRT7 might regulate p65 nuclear translocation indirectly by deacetylating p65-interacting proteins. Further studies are necessary to address how SIRT7 regulates p65 translocation to the nucleus.

Several studies have shown that KD of Sirt7 increases apoptosis in vitro54,55. We also found that Sirt7 KD promoted apoptosis in NRK-52E cells (data not shown). In contrast, fewer TUNEL-positive cells were noted in the kidney of Sirt7 KO mice compared with WT mice. Cisplatin-induced proinflammatory cytokines increase apoptosis in renal cells56,57. Thus, inhibition of the recruitment and accumulation of inflammatory cells by the suppression of cytokines and chemokines in Sirt7 KO mice might be responsible for the overall anti-apoptosis effect in vivo. Further studies are also needed to clarify the relationship between SIRT7 and apoptosis.

In conclusion, these results demonstrated that SIRT7 deficiency ameliorated cisplatin-induced AKI in mice. Our findings suggest that SIRT7 is an important novel therapeutic target for cisplatin-induced AKI.

Methods

Animal Experiments

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Committee of Kumamoto University and were approved by the Committee on Animal Research at Kumamoto University. Except when indicated, 10-week-old WT and Sirt7 KO mice with a C57/BL6J background were used for this study. The generation of Sirt7 KO mice and Sirt7 FRT/floxed mice was described previously10,58. The mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12:12-h light–dark cycle and were fed a standard normal diet ad libitum with free access to water. Cisplatin (cis-diammineplatinum(II) dichloride; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in normal saline at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, and was given by intraperitoneal injection of 20 mg/kg body weight as described previously59. Metabolic cages were used for 24-h urine collections. Blood and kidneys were harvested at 72 h after cisplatin injection. Serum chemistry analysis was performed by a commercial laboratory (SRL, Tokyo, Japan).

Urinary NGAL Concentrations

We collected 24-h urine samples at days 1, 2, and 3 after cisplatin injection. Urinary NGAL concentrations were measured using a mouse NGAL ELISA Kit (BioPorto Diagnostics, Gentofte, Denmark). For creatinine adjustment, urine creatinine levels were measured using a Lab Assay Creatinine Kit (Wako, Osaka, Japan).

Histology and Tubular Injury Score

The kidneys were fixed with 10% formalin neutral buffer solution and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4-μm thick) were stained using Periodic acid-Schiff and examined under a light microscope. The tubular injury score was calculated on a scale of 0–5 on the basis of the percentage of tubules with necrosis, cast formation, dilation, or loss of the brush border: 0, 0%; 1, 1–10%; 2, 11–25%; 3, 26–45%; 4, 46–75%; and 5, 76–100%60. A pathologist evaluated 5 randomly selected fields per section of the mouse kidney at a magnification of ×400 in a blind manner.

β-Galactosidase (lacZ) Staining

Kidney sections harvested from Sirt7 FRT/floxed and WT mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h at 4 °C. Fixed sections were washed with 0.02% NP-40 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min and PBS for 20 min 3 times. After washing, the sections were transferred to an X-gal solution (0.5 mg/mL X-gal, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 1 mM MgCl2) and incubated at 37 °C overnight.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Deparaffinized sections were subjected to microwave pretreatment with a pH 6.0 citrate buffer for p65 immunostaining or pretreatment with proteinase K for F4/80 immunostaining61. After the reaction of each primary antibody (anti-p65 antibody, #8242, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, and anti-F4/80 antibody clone CI:A3-1, Serotec, Oxford, UK), the samples were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rat or goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). The reaction was visualized using the diaminobenzidine system (Nichirei).

For immunostaining of SIRT7 and lectin, deparaffinized sections were incubated in HistoVT One solution (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) for 40 min at 90 °C. After reaction with an anti-SIRT7 antibody (1:300, #5360, Cell Signaling Technology), the sections were reacted with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody and HRP-labeled streptavidin (Nichirei). The reaction was visualized with diaminobenzidine (brown) as above. After the sections were rinsed with 100 mM glycine-HCL buffer (pH 2.2) to remove the primary and secondary antibodies, the sections were reacted with biotinylated PHA-E (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or DBA (Vector Laboratories) and then incubated with HRP-labeled streptavidin. The reaction was visualized with HistoGreen (Linaris, Heidelberg, Germany) (green).

TUNEL Assay

TUNEL assay was performed with a commercially available detection kit (In situ Apoptosis Detection Kit; Takara, Shiga, Japan).

Cell Culture

Rat kidney proximal tubular cells (NRK-52E) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). NRK-52E cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 25 mM glucose, 1.0 mM pyruvate, 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, and 0.1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

SIRT7 Gene Silencing

For KD of SIRT7, oligonucleotides encoding SIRT7 shRNA (target sequence: shSirt7, 5′-GGGACACCATTGTGCACTT-3′) were cloned into the pSIREN-RetroQ expression vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). After the pSIREN-RetroQ-SIRT7 or pSIREN-RetroQ-control vector was transfected into Plat-E cells, the retrovirus-containing medium was mixed with Polybrene and added to NRK-52E cells for infection. Selection was achieved using puromycin treatment (5 µg/mL).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA from mouse kidneys and NRK-52E cells was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). cDNA synthesis was then achieved with a Prime Script RT Reagent Kit (Takara). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using TaqMan probes for mouse Tnfa, Il1b, Il6 (Sigma Aldrich), Ccl2, Cxcl2, Cybb, Ncf1, Sod1, Sod2, Slc22a2, Slc47a1, and Gapdh, and rat Tnfa, Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, Cxcl2, Cybb, Ncf1, and Gapdh (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the Light Cycler 480 Sequence Detector System (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), or primers for mouse Sirt1–7, Acox1, Cycs, Cat, and Gapdh with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara) in an ABI 7300 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems). The results were analyzed statistically based on ΔCT values (Ct gene of interest − CT GAPDH). Relative gene expression was obtained using the ΔΔCt method (Ct sample − Ct calibrator).

Western Blotting

Total lysates of cells and kidney tissues were obtained by lysis in RIPA Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mg/mL Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM PMSF) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque). Nuclear fractions of cells and kidney tissues were prepared using a LysoPure™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extractor Kit (Wako) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Aliquots of proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in a reduced condition and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA), which was probed with the primary antibodies. After incubation with the secondary antibodies, proteins were visualized using Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nacalai Tesque) and a LAS-1000 imaging system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Primary antibodies included an anti-SIRT7 antibody (#5360, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody (#9661, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-p65 antibody (#4764, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-p65 antibody (#3031, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-IκBα antibody (#9242, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-β-actin antibody (A5060, Sigma Aldrich), anti-GAPDH antibody (#2118, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-histone H3 antibody (#39163, Active Motif).

Immunofluorescence

Each chamber of a 4-chamber 35-mm glass bottom dish were seeded with 5.0 × 103 shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells and incubated for 24 h. Then, the cells were transfected with 0.5 μg pCI-HA-p65 expression plasmid in each chamber using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection, Strasbourg, France). At 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with or without 30 μM cisplatin for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed in a 10% formalin neutral buffer solution for 15 min. The fixed cells were incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min to permeabilize the cells. In the blocking step, the cells were covered with Blocking One (Nacalai Tesque) for 20 min. The cells were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies against the hemagglutinin (HA) tag (1:500, Roche Diagnostics). To detect the primary antibody, the sections were incubated with anti-rat Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated antibodies (1:1000, Life Technologies). Hoechst 33342 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was used for nuclear staining. The fluorescence intensity in the regions of interests (ROI) in the nucleus and cytoplasm was measured using ImageJ software, as described previously62. Relative fluorescence intensity is represented by the ratio of nuclear fluorescence intensity to cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity.

Luciferase Assay

The NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid (pNF-κB-Luc, Takara) was used for measuring NF-κB activity, and the pRL-TK plasmid was used as an internal control. The pCI-HA-p65 expression plasmid was used for examining the expression of p65, and the pCI-HA-control plasmid was used as a control. The pCI-HA-p65 expression plasmid was constructed as follows: the HA tag was inserted into the pCI-p65 expression plasmid (gifted from Dr. Takashi Minami) by PCR using HA-containing primers. The pcDNA3-FLAG-Sirt7 expression plasmid was used for the expression of Sirt7, and the pcDNA3-FLAG-control plasmid was used as a control.

The shRNA-introduced NRK-52E cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 7.5 × 104 cells/well and maintained for 24 h. Subsequently, the pNF-κB-Luc plasmid and pRL-TK plasmid were co-transfected into the cells with expression plasmids using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection). The luciferase assay was performed 24 h later with the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-FLAG-p65 and either pcDNA3-HA, pcDNA3-HA-Sirt1, or pcDNA3-HA-Sirt7 using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection). After 24 h, the cells were lysed using a 27 G syringe in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail [Nacalai Tesque]). The soluble cellular fractions were recovered by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Then, 700 μg cell lysate was mixed with FLAG-tag antibody beads (Wako) and stirred at 4 °C for 15 h. After washing with IP buffer, proteins were eluted with 1 × SDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 0.2% bromophenol blue) for western blotting. Binding of SIRT7 protein to p65 was detected with a rat anti-HA high affinity antibody (3F10; Roche Diagnostics).

Detection of Lysine Acetylation

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-FLAG-p65, pCMVβ-p300-myc, and either pcDNA3-HA, pcDNA3-HA-Sirt7, or pcDNA3-HA-Sirt1 using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection). After 36 h, the cells were lysed with a 27 G syringe in IP buffer. The soluble cell fractions were recovered by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Then, 500 μg cell lysate was mixed with FLAG-tag antibody beads (Wako) and stirred at 4 °C for 6 h. After washing with IP buffer, proteins were eluted with 1× SDS sample buffer and subjected to western blotting. Acetylation of p65 protein was detected with a Pan anti-acetyl lysine rabbit polyclonal antibody (TM-105; PTM Biolabs, Chicago, IL). pCMVβ-p300-myc was a gift from Tso-Pang Yao (Addgene plasmid # 30489).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between subject groups were analyzed with Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Survival rates were analyzed by the log-rank test. For comparisons among more than two groups, analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s correction was used. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and were prepared in Excel or GraphPad Prism.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Yuichiro Arima and Dr. Satoshi Araki (Department of Cardiology, Kumamoto University), Dr. Tsuyoshi Kadomatsu (Department of Molecular Genetics, Kumamoto University), Dr. Takeshi Matsumura (Department of Metabolic Medicine, Kumamoto University), Dr. Kunimasa Ohta (Department of Developmental Neurobiology, Kumamoto University), and Ms. Noriko Nakagawa and Ms. Naoko Hirano (Department of Nephrology, Kumamoto University) for their helpful discussions and experimental support. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (to K.Y.), a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP17gm5010002) (to K.Y.), a grant from the Naito Foundation (to K.Y.), a grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to K.Y.), and a grant from the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (to K.Y. and Yoshikazu Miyasato).

Author Contributions

Yoshikazu Miyasato, T.Y., and K.Y. designed the research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Yoshikazu Miyasato, Y.S., T.N. and Yuko Miyasato performed the experiments. Yutaka Kakizoe, T.K., M.A., A.I., T.B. and Yoshihiro Komohara helped with data acquisition and discussion of the data. Yoshikazu Miyasato and K.Y. analyzed the data and prepared the figures. M.M. and K.Y. supervised the whole project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Tatsuya Yoshizawa, Yoshifumi Sato, Terumasa Nakagawa and Yuko Miyasato contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-24257-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel). 2010;2:2490–2518. doi: 10.3390/toxins2112490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozkok, A. & Edelstein, C. L. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res. Int. 2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Pabla N, Dong Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 2008;73:994–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavu S, Boss O, Elliott PJ, Lambert PD. Sirtuins–novel therapeutic targets to treat age-associated diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:841–853. doi: 10.1038/nrd2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa K, et al. Kidney-specific overexpression of Sirt1 protects against acute kidney injury by retaining peroxisome function. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:13045–13056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DH, et al. SIRT1 activation by resveratrol ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal injury through deacetylation ofp53. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F427–435. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00258.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morigi M, et al. Sirtuin 3-dependent mitochondrial dynamic improvements protect against acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:715–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI77632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barber MF, et al. SIRT7 links H3K18 deacetylation to maintenance of oncogenic transformation. Nature. 2012;487:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshizawa T, et al. SIRT7 controls hepatic lipid metabolism by regulating the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell Metab. 2014;19:712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford E, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription service Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1075–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin J, et al. SIRT7 represses myc activity to suppress er stress and prevent fatty liver disease. Cell Rep. 2013;5:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryu D, et al. A SIRT7-dependent acetylation switch of GABPβ1 controls mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 2014;20:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki S, et al. Sirt7 Contributes to Myocardial Tissue Repair by Maintaining Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling Pathway. Circulation. 2015;132:1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang J, et al. Sirt7 promotes adipogenesis in the mouse by inhibiting autocatalytic activation of Sirt1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:E8352–E8361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706945114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill MS, et al. APOBEC3G expression is restricted to epithelial cells of the proximal convoluted tubules and is not expressed in the glomeruli of macaques. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2007;55:63–70. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7054.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra J, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerhart-Hines Z, et al. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1α. EMBO J. 2007;26:1913–1923. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong Y, Wang M, Zhao J, Han Y, Jia L. Sirtuin 3: A Janus face in cancer (Review) Int. J. Oncol. 2016;49:2227–2235. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciarimboli G, et al. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity is critically mediated via the human organic cation transporter 2. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yonezawa A, Inui KI. Organic cation transporter OCT/SLC22A and H+/organic cation antiporter MATE/SLC47A are key molecules for nephrotoxicity of platinum agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ucero AC, et al. Unilateral ureteral obstruction: Beyond obstruction. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014;46:765–776. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramesh G, Reeves WB. TNF-α mediates chemokine and cytokine expression and renal injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:835–842. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrier RW. Cancer therapy and renal injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:743–745. doi: 10.1172/JCI0216568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faubel S, et al. Cisplatin-Induced Acute Renal Failure Is Associated with an Increase in the Cytokines Interleukin (IL) -1β, IL-18, IL-6, and Neutrophil Infiltration in the Kidney. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;322:8–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF- κB in defense and disease NF- κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shakhov AN, Collart MA, Vassali P, Nedospasov SA, Jongeneel CV. kB-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the Tumor Necrosis Factor a gene in primary macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 1990;171:35–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha J, Lee Y, Kim HH. CXCL2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclastogenesis in RANKL-primed precursors. Cytokine. 2011;55:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HY, Kim HS. Upregulation of MIP-2 (CXCL2) expression by 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007;85:60–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared Principles in NF-κB Signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanz AB, et al. NF-κB in Renal Inflammation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1254–1262. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung F, et al. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369–2380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothgiesser KM, Erener S, Waibel S, Lüscher B, Hottiger MO. SIRT2 regulates NF-κB dependent gene expression through deacetylation of p65 Lys310. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:4251–4258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawahara TLA, et al. SIRT6 Links Histone H3 Lysine 9 Deacetylation to NF-κB-Dependent Gene Expression and Organismal Life Span. Cell. 2009;136:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park MY, Jang HD, Lee SY, Lee KJ, Kim E. Fas-associated Factor-1 Inhibits Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) Activity by Interfering with Nuclear Translocation of the RelA (p65) Subunit of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2544–2549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You DJ, et al. A splicing variant of NME1 negatively regulates NF-κB signaling and inhibits cancer metastasis by interacting with IKKβ. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17709–17720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim RH, et al. SNIP1 Inhibits NF-κB Signaling by Competing for Its Binding to the C/H1 Domain of CBP/p300 Transcriptional Co-activators. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46297–46304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garkavtsev I, et al. The candidate tumour suppressor protein ING4 regulates brain tumour growth and angiogenesis. Nature. 2004;428:328–332. doi: 10.1038/nature02329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou Y, et al. Inhibitor of growth 4 induces NFκB/p65 ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Oncogene. 2013;33:1997–2003. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mankan AK, Lawless MW, Gray SG, Kelleher D, McManus R. NF-κB regulation: The nuclear response. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:631–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou C, et al. MicroRNA-372 maintains oncogene characteristics by targeting TNFAIP1 and affects NFκB signaling in human gastric carcinoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2013;42:635–642. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anrather, J., Racchumi, G. & Iadecola, C. NF-κB Regulates Phagocytic NADPH Oxidase by Inducing the Expression of gp91 phox. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5657–5667 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Gauss KA, et al. Role of NF-κB in transcriptional regulation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase by tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;82:729–741. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung YJ, et al. SIRT2 Regulates LPS-Induced Renal Tubular CXCL2 and CCL2 Expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;26:1549–1560. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshizaki T, et al. SIRT1 inhibits inflammatory pathways in macrophages and modulates insulin sensitivity. AJP Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;298:E419–E428. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00417.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo Sasso, G. et al. SIRT2 deficiency modulates macrophage polarization and susceptibility to experimental colitis. PLoS One9, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Huang B, Yang XD, Lamb A, Chen LF. Posttranslational modifications of NF-kappaB: another layer of regulation for NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell. Signal. 2010;22:1282–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:81–96. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang TT, Kudo N, Yoshida M, Miyamoto S. A nuclear export signal in the N-terminal regulatory domain of IkappaBalpha controls cytoplasmic localization of inactive NF-kappaB/IkappaBalpha complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:1014–1019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson C, Van Antwerp D, Hope TJ. An N-terminal nuclear export signal is required for the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 1999;18:6682–93. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L, et al. SIRT7 is a histone desuccinylase that functionally links to chromatin compaction and genome stability. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12235. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tong Z, et al. SIRT7 Is an RNA-Activated Protein Lysine Deacylase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:300–310. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang XJ, Seto E. Lysine Acetylation: Codified Crosstalk with Other Posttranslational Modifications. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang HL, et al. SIRT7 Exhibits Oncogenic Potential in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3573–3577. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.8.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S, et al. Sirt7 promotes gastric cancer growth and inhibits apoptosis by epigenetically inhibiting miR-34a. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9787. doi: 10.1038/srep09787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Inflammatory cytokines in acute renal failure. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2004;66:S56–S61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang H, Zhang Z, He L, Wang Y. CXCL16 regulates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Oncotarget. 2016;7:31652–31662. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vakhrusheva O, et al. Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ. Res. 2008;102:703–710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oh GS, et al. Pharmacological activation of NQO1 increases NAD levels and attenuates cisplatin-mediated acute kidney injury in mice. Kidney Int. 2013;85:547–560. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi S, Wu D. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury in rats by inhibiting cell apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013;32:1262–72. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakagawa T, et al. Optimum immunohistochemical procedures for analysis of macrophages in human and mouse formalin fixed paraffin- embedded tissue samples. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 2017;57:31–36. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.17017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kagoya Y, et al. Positive feedback between NF-kappaB and TNF-alpha promotes leukemia-initiating cell capacity. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:528–542. doi: 10.1172/JCI68101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.