ABSTRACT

The primary cilium is a microtubule-based organelle required for Hedgehog (Hh) signaling and consists of a basal body, a ciliary axoneme and a compartment between the first two structures, called the transition zone (TZ). The TZ serves as a gatekeeper to control protein composition in cilia, but less is known about its role in ciliary bud formation. Here, we show that centrosomal protein Dzip1l is required for Hh signaling between Smoothened and Sufu. Dzip1l colocalizes with basal body appendage proteins and Rpgrip1l, a TZ protein. Loss of Dzip1l results in reduced ciliogenesis and dysmorphic cilia in vivo. Dzip1l interacts with, and acts upstream of, Cby, an appendage protein, in ciliogenesis. Dzip1l also has overlapping functions with Bromi (Tbc1d32) in ciliogenesis, cilia morphogenesis and neural tube patterning. Loss of Dzip1l arrests ciliogenesis at the stage of ciliary bud formation from the TZ. Consistent with this, Dzip1l mutant cells fail to remove the capping protein Cp110 (Ccp110) from the distal end of mother centrioles and to recruit Rpgrip1l to the TZ. Therefore, Dzip1l promotes ciliary bud formation and is required for the integrity of the TZ.

KEY WORDS: Dzip1l, Chibby, Bromi, Cilia, Hedgehog, Gli2, Gli3, Mouse

Summary: Dzip1l functions in ciliary initiation and morphogenesis and the integrity of the transition zone, with mutants showing reduced Hedgehog signaling between Smo and Sufu, expanded brain size and polydactyly.

INTRODUCTION

The primary cilium is a microtubule-based organelle that protrudes from the cell surface of most vertebrate cells. It serves as a sensory organelle and also functions in transducing extracellular signals, such as Hedgehog (Hh), Wnt and PDGF. Defects in ciliary structure and function lead to a diverse array of developmental abnormalities and metabolic diseases, including open brain, holoprosencephaly, polydactyly, microphthalmia, cystic kidney disease, retinal degeneration, and obesity, which are collectively termed ‘ciliopathies’ (Bangs and Anderson, 2017; Gerdes et al., 2009; Reiter and Leroux, 2017).

Most of the developmental abnormalities caused by ciliary gene mutations result from the disruption of Hh signaling from Smoothened (Smo), a seven transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor, to Gli2 and Gli3 transcription regulators (Bangs and Anderson, 2017). As a consequence, the processing of Gli2 and Gli3 into their C-terminally truncated repressors is reduced, and Gli2 and Gli3 full-length activators are less active, although their levels are increased. The exact step(s) between Smo and Gli2/Gli3 at which the ciliary proteins act is unknown.

Primary cilia originate from the mother centriole of the centrosome when cells exit the cell cycle to enter quiescence (Go). Cilia are absorbed when cells re-enter the cell cycle (Kobayashi and Dynlacht, 2011; Nigg and Stearns, 2011). In cultured cells, primary cilia formation begins with the docking of ciliary membrane vesicles to the mother centriole or basal body (Schmidt et al., 2012; Sorokin, 1962; Tanos et al., 2013), followed by the removal of the capping protein Cp110 (Ccp110) from the distal end of the mother centriole (Schmidt et al., 2009; Spektor et al., 2007), the recruitment of intraflagellar transport (IFT) protein complexes (Pazour et al., 2000; Qin et al., 2004; Rosenbaum and Witman, 2002), the formation of the transition zone (TZ) (Chih et al., 2011; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011), the elongation of the ciliary axoneme, and the fusion of ciliary vesicles with the plasma membrane to expose cilia to the extracellular space (Garcia-Gonzalo and Reiter, 2017; Pedersen and Rosenbaum, 2008).

The docking of ciliary vesicles to basal bodies requires distal appendages, accessary basal body structures that were initially identified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as electron-dense structures (Sorokin, 1962). Several recent studies showed that the distal appendage components, including Cep164 and several other proteins, are essential for the docking of a ciliary vesicle to a basal body (Burke et al., 2014; Joo et al., 2013; Schmidt et al., 2012; Tanos et al., 2013; Tateishi et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2014).

The TZ is a specialized compartment between the basal body and ciliary axoneme, and its assembly is dependent on Cep162 (Wang et al., 2012). It serves as a ciliary gate that works together with the septin ring (Hu et al., 2010) and nucleoporins (Kee et al., 2012), and probably with distal appendages, to selectively regulate protein transport to, and exit from, the ciliary compartment. Several multiprotein complexes, including NPHP1-4-8, MKS/B9 and Cep290/NPHP5 complexes, have been found at the TZ, and many are associated with ciliopathies (Chih et al., 2011; Dowdle et al., 2011; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Lambacher et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Roberson et al., 2015; Sang et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2017; Shylo et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2011). These protein complexes are required not only for ciliary biogenesis and protein composition in cilia, but also for a sensory function.

Dzip1 and Dzip1l are two mammalian homologs of the zebrafish iguana (igu) gene, which was initially identified for its role in Hh signaling and later in ciliogenesis (Glazer et al., 2010; Sekimizu et al., 2004; Tay et al., 2010; Wolff et al., 2004). Studies from our lab and others showed that Dzip1 and Dzip1l localize to mother centrioles (Glazer et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Analysis of a Dzip1 mutant mouse line that we had generated revealed that Dzip1 is required for ciliogenesis, Gli3 processing and Gli2 activation (Wang et al., 2013). A recent study showed that Dzip1l is a TZ protein and that a Dzip1l mutation affects Hh signaling and ciliary function but not ciliogenesis in vivo, although ciliogenesis was compromised in cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Lu et al., 2017). Therefore, whether and how Dzip1l regulates ciliogenesis in vivo remain to be determined.

In the present study, we show that loss of Dzip1l gene function results in reduced ciliogenesis and bulged cilia in vivo. As a consequence, Hh signaling is compromised and Gli3 processing, which generates Gli3Rep, is reduced. Mice homozygous for the Dzip1l mutation display enlarged brain and polydactyly. The localization of Dzip1l at the mother centriole partially overlaps with that of the appendage proteins of the mother centriole and Rpgrip1l (also known as Ftm), a TZ protein (Arts et al., 2007; Delous et al., 2007; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Gerhardt et al., 2015; Mahuzier et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2017; Vierkotten et al., 2007). Dzip1l interacts with Chibby (Cby), a component of mother centriolar appendages (Burke et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Steere et al., 2012), and both function in a linear pathway to regulate ciliogenesis. Dzip1l also genetically interacts with Bromi (Tbc1d32), mutations of which affect ciliary morphology and function but not ciliogenesis (Ko et al., 2010), to collaboratively control ciliogenesis and cilia morphology in vivo. Mechanistically, loss of Dzip1l arrests ciliogenesis at the stage of ciliary bud formation from the TZ. Consistent with this, the capping protein Cp110 fails to be removed from the distal end of the mother centriole, and Rpgrip1l is not recruited to the mother centrioles in Dzip1l mutant cells. Thus, Dzip1l is required for the remodeling of the distal end of the mother centriole and the integrity of the TZ, which in turn promotes ciliary bud formation.

RESULTS

Loss of Dzip1l results in a defect in Hh signaling

To understand Dzip1l function in vivo, we used a targeted gene-knockout approach to generate a Dzip1l mutant allele by deleting exons 4-6 of the gene in mice. The allele is designated as Dzip1l– in figures (Fig. 1A,B). The deletion was expected to cause a reading frame shift and a stop codon after the 195th aa residue, if exon 3 were spliced to exon 7. Thus, the mutant protein, if expressed, would contain the single zinc-finger domain (166-189 aa) but no coiled-coil domain (204-450 aa).

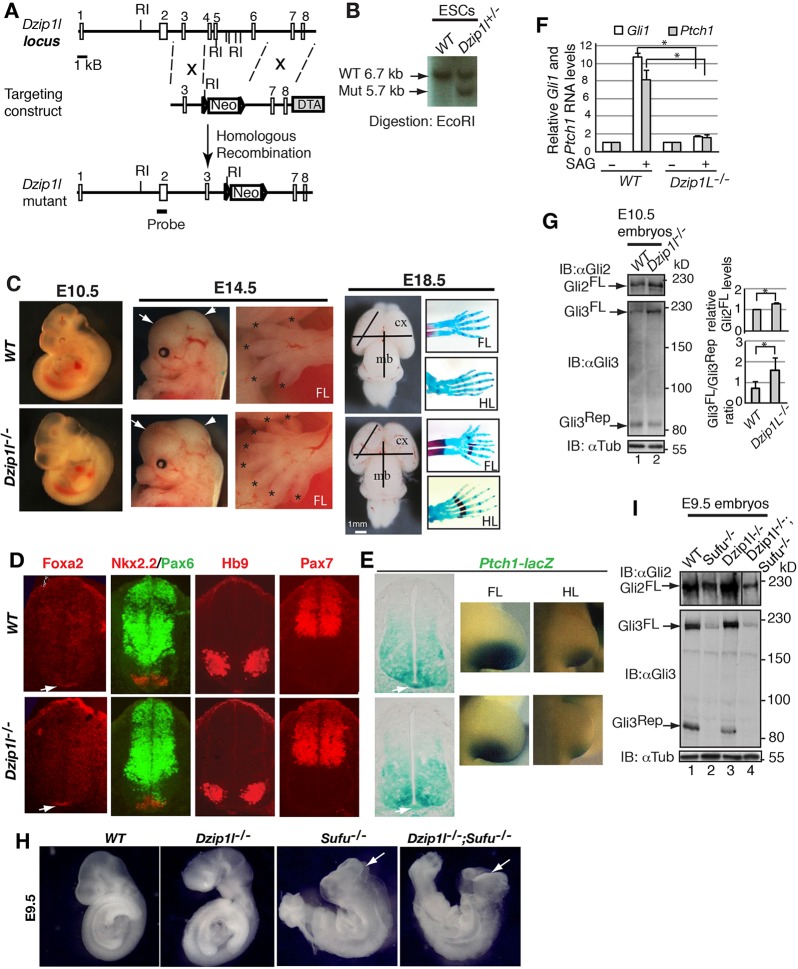

Fig. 1.

Loss of Dzip1l results in reduced Hh signaling, expanded brain size and polydactyly in mice. (A) The gene-targeting strategy used to create a mouse Dzip1l mutant allele. Open rectangles represent exons and lines represent introns. The probe used for Southern blots is shown. Triangles indicate the loxP site. Neo, neomycin; DTA, diphtheria toxin A; number, exons; RI, EcoRI. (B) Southern blot of representative mutant and wt ESC clones (n=1 experiment). (C) The morphology of wt and Dzip1l mutant embryos at E10.5, head and limb at E14.5, and brain and limb skeleton at E18.5. Expanded brain and polydactyly in mutant embryos are noted. Forebrain and midbrain are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. Digits are labeled with asterisks. Brain size is measured by lines with the same length. FL, forelimb; HL, hind limb; cx, cortex; mb, midbrain. n=12/12 embryos. (D) Neural tube patterning appears to be normal in Dzip1l mutants. E10.5 neural tube sections were immunostained for the indicated protein markers. The Foxa2+ floor plate is indicated by arrows (n≥4 sections from 2-3 embryos). (E) lacZ expression directed by the Ptch1 promoter is reduced in the mutant. E10.5 embryos with indicated genotypes were subject to lacZ staining and subsequently sectioned. Staining of the floor plate (indicated by arrow) in the mutant is weaker than that in wt (n=3 embryos). (F) Gli1 and Ptch1 RNA expression levels in wt pMEFs are significantly higher than those in Dzip1l mutant pMEFs upon Smo activation. RT-qPCR shows Gli1 and Ptch1 RNA expression levels before and after stimulation of wt and mutant pMEFs with SAG, a Smo agonist. Two-tailed Student's t-test P≤0.0004 (n=3 experiments). Asterisks indicate significance. (G) Increased Gli2FL protein level and reduced Gli3 processing in Dzip1l mutant embryos. Immunoblot results show Gli2FL, Gli3FL and Gli3Rep levels in wt and Dzip1l mutant embryos. Graphs to the right show quantitative results. Immunoblot with α-tubulin (αTub) is a loading control. Two-tailed Student's t-test P≤0.036 (n=3). Asterisk indicates the significance. (H,I) Sufu is epistatic to Dzip1l in Hh signaling. Dzip1l−/−;Sufu−/− embryo phenotypes resemble those of Sufu−/− embryo. Arrows point to exencephaly (n=3/3 embryos). (I) Western blot shows that Gli2FL, Gli3FL and Gli3Rep levels in Dzip1l−/−;Sufu−/− embryo are similar to those in Sufu−/− embryo (I) (n=1 experiment).

Mice homozygous for the Dzip1l mutation died between embryonic day (E) 14.5 and birth (n≥60 embryos and pups). At E10.5, the gross morphology of mutant embryos was similar to that of wild type (wt). However, at E14.5, enlarged brain size (occasionally open brain) and polydactyly became apparent (n=12/12). These phenotypes were confirmed by measurement of brain size and limb skeletons of E18.5 embryos (Fig. 1C).

Given that expanded brain size and polydactyly are often associated with Hh signaling, we next examined neural tube patterning of the Dzip1l mutant embryos. In wt embryos, Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) expressed in the notochord specifies and patterns different ventral neural cell types, including the floor plate marked by Foxa2, Nkx2.2 (Nkx2-2)+ p3 interneuron progenitors and Hb9 (Mnx1)+ motoneurons. Shh signaling also restricts the ventral expression of dorsal neural cell types labeled by Pax6 and Pax7 (Briscoe et al., 2000). Surprisingly, all these neural cell types appeared to be generated and patterned normally in Dzip1l mutant embryos (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the effect of Dzip1l mutation on Hh signaling in neural tube patterning, if any, is subtle, given that Dzip1l is expressed in spinal cord and many other tissues of mouse embryos (Fig. S1).

To directly monitor whether Hh signaling is affected in Dzip1l mutants, the Dzip1l mutant allele was crossed into a Ptch1-lacZ knock-in reporter line background so that Hh signaling activity could be assessed by lacZ expression levels (Goodrich et al., 1997). The lacZ expression levels in both the floor plate and posterior region of limb buds of mutant mice were slightly lower than those in wt (Fig. 1E), suggesting that Hh signaling is reduced in the Dzip1l mutant.

To further determine whether Hh signaling is impacted in Dzip1l mutants, the response of primary MEFs (pMEFs) to stimulation with the Smo agonist SAG (Chen et al., 2002) was examined. RT-qPCR analysis showed that Ptch1 and Gli1 RNA expression were increased ∼10- and 8-fold, respectively, in wt pMEFs upon SAG stimulation, whereas they were upregulated only ∼0.5-fold in the mutant pMEFs (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results indicate that Hh signaling is compromised in Dzip1l mutants.

Given that Gli2 and Gli3 are the transcription regulators that primarily mediate Hh signaling (Bai et al., 2004), we next examined Gli2 and Gli3 protein levels in Dzip1l mutants. Western blotting showed that both Gli2 and Gli3 full-length protein (Gli2FL and Gli3FL) levels were increased in the mutant compared with wt, but that Gli3 repressor (Gli3Rep) levels were reduced (Fig. 1G), indicating that Gli3 processing, which generates Gli3Rep from Gli3FL (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Li, 2006), is reduced in the Dzip1l mutant. In addition, because Hh signaling was decreased in the mutant, but Gli2FL and Gli3FL levels are increased, these results also indicate that Gli2FL and Gli3FL are less active in the mutant than in wt.

Sufu is a negative effector that inhibits Gli2 and Gli3 transcriptional activity (Cooper et al., 2005; Ding et al., 1999; Murone et al., 2000; Svärd et al., 2006) and is also required for Gli2FL and Gli3FL stability (Chen et al., 2009; Jia et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). To determine the epistasis between Dzip1l and Sufu, Dzip1l mutants were crossed with Sufu mutants (Wang et al., 2010) to finally generate Dzip1l;Sufu double-mutant embryos. Interestingly, Dzip1l;Sufu double-mutant embryos exhibited exencephaly, which resembled that of Sufu, but not Dzip1l, mutant embryos (Fig. 1H). In support of this, as in Sufu mutants, Gli2FL and Gli3FL levels in the double-mutant embryos were markedly reduced (Fig. 1I). Thus, Sufu acts downstream of Dzip1l in the regulation of Gli2 and Gli3 function.

Bulged cilia and reduced ciliogenesis in Dzip1l mutants

The Dzip1l mutant phenotypes described above resembled those of ciliary gene mutants (Bangs and Anderson, 2017). Thus, we wanted to know whether ciliogenesis is affected in Dzip1l mutants. Immunofluorescence of E10.5 mouse embryo sections for the ciliary markers Arl13b and acetylated α-tubulin showed that cilia density on both neuroepithelia in the neural tube and mesenchymal cells in the limb buds of Dzip1l mutants were lower than in those of wt. Quantitative analysis indicated that number of cilia in the mutant was only approximately half that in wt. In pMEFs, the difference in the percentage of ciliated cells between mutant and wt was even greater: 3% versus 40% (Fig. 2A).

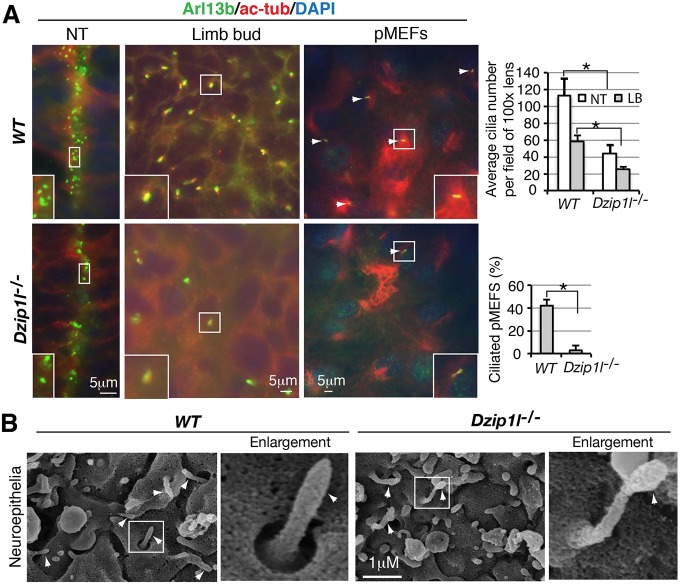

Fig. 2.

Ciliogenesis is reduced and cilia are bulged in Dzip1l mutant. (A) Reduced cilia number in Dzip1l mutants. Neural tube and limb bud sections and pMEFs of wt and Dzip1l mutant embryos were stained for ciliary markers Arl13b and acetylated tubulin (ac-Tub). Average cilia number per field under 100× lens (n≥5 sections from two embryos for each genotype) or percentage of ciliated pMEFs (n≥100 cells) were quantified and are shown to the right. NT, neural tube; LB, limb bud. *P≤0.00026, two-tailed Student's t-test. (B) Micrographs of SEM of neuroepithelia in wt and Dzip1l mutant neural tubes. Some cilia in Dzip1l mutants are bulged. Arrowheads point to cilia. The framed cilia are enlarged and shown to the right (n=2 experiments).

Given that some cilia were formed in Dzip1l mutant embryos, we wanted to know whether ciliary morphology was normal in the mutants. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed that some cilia on neuroepithelia in the lumen of the mutant neural tube were bulged at their tips (Fig. 2B), suggesting that there is an imbalance in anterograde and retrograde IFT trafficking. Taken together, these observations indicate that ciliogenesis is reduced and cilia are dysmorphic in Dzip1l mutant embryos.

Bulged cilia are often associated with the accumulation of proteins in cilia. Thus, we wondered whether Smo, Gli2 and Gli3 accumulate in Dzip1l mutant cilia. Wt and Dzip1l mutant pMEFs were either treated, or not, with SAG and then subjected to immunostaining for Smo, Gli2 or Gli3 together with ciliary markers Arl13b or acetylated α-tubulin. Without SAG stimulation, Smo was undetectable in wt cilia and occasionally detected in Dzip1l mutant cilia (3.4% of cilia). Upon SAG stimulation, 42.2% of wt and 42.9% of mutant cilia were Smo+ (Fig. 3), indicating that Smo ciliary localization is responsive to Hh signaling in both wt and Dzip1l mutant cells. By contrast, although, as expected, SAG stimulation significantly increased the percentage of Gli2+ and Gli3+ cilia in wt cells (41.5% versus 80% and 29.3% versus 73.7%, respectively), it did not do so in the mutant cells (65.4% versus 60.4% and 60.3% versus 57%, respectively). In addition, the percentages of Gli2+ and Gli3+ cilia in ciliated Dzip1l mutant cells without SAG stimulation were significantly higher than in ciliated wt cells (65.4% and 60.3% in mutant versus 41.5% and 29.3% in wt, respectively, P=0.012 and P=0.026, respectively) (Fig. 3). Together, these results indicate that Gli2 and Gli3 accumulate in Dzip1l mutant cilia, which is consistent with bulged cilia morphology (Fig. 2B), and that Hh signaling between Smo and Gli2/Gli3 is impaired in Dzip1l mutant cells.

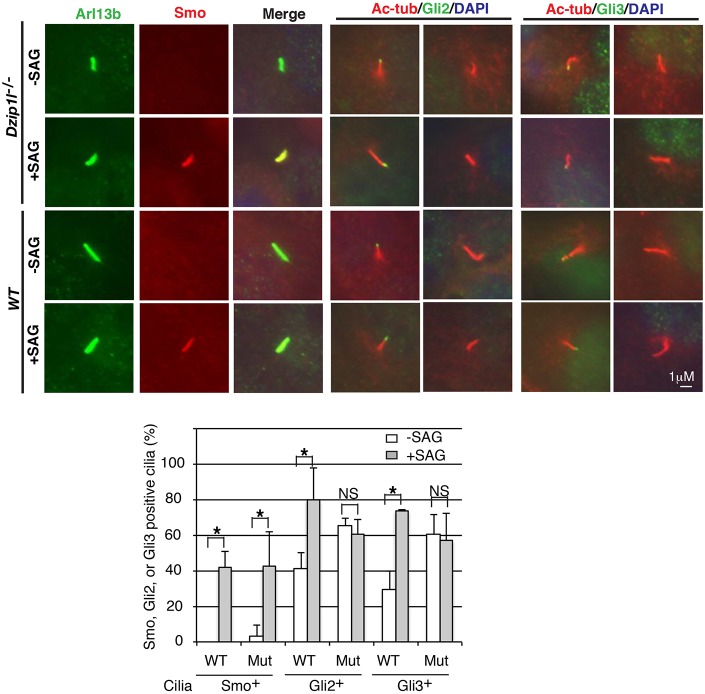

Fig. 3.

Dzip1l mutant cells fail to respond to SAG stimulation with respect to Gli2/Gli3 ciliary localization. Both wt and Dzip1l mutant pMEFs were treated with SAG overnight and then subjected to immunostaining for the proteins as indicated. The graph is derived from three independent experiments (cilia number n ≥30 for mutant and ≥100 for wt per experiment). Ciliary localization of Smo, but not Gli2 and Gli3, is responsive to SAG treatment and Gli2 and Gli3 accumulate in Dzip1l mutant cilia compared with wt in the absence of SAG. *P≤0.028, two-tailed Student's t-test. P=0.012 and P=0.026 for Gli2+ and Gli3+ cilia between wt and the mutant in the absence of SAG, respectively.

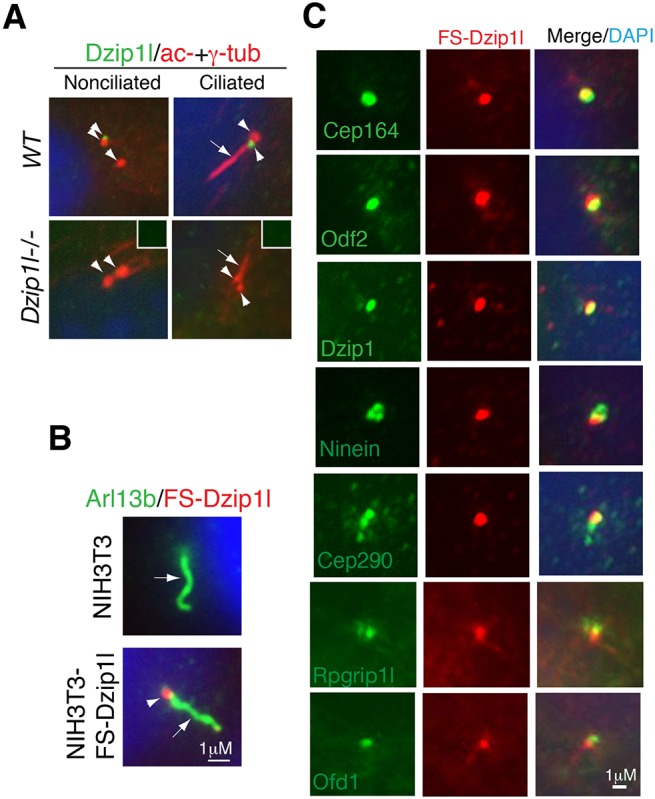

Dzip1l partially colocalizes with basal body appendage and transition zone proteins

To understand how the loss of Dzip1l might affect ciliogenesis and function, the subcellular localization of Dzip1l was examined. Immunostaining with a Dzip1l antibody showed specific signal between the basal body (γ-tubulin staining) and the axoneme (acetylated α-tubulin staining) in ciliated wt pMEFs or next to one of the two centrioles (presumably the mother centriole) in nonciliated wt cells but not in mutant pMEFs (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that Dzip1l staining is specific and that the Dzip1l protein is recruited to the mother centriole independent of a fully assembled axoneme. This was verified by immunostaining of NIH3T3 cells stably expressing FLAG- and Strep-tagged Dzip1l (FS-Dzip1l) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Dzip1l colocalizes partially with appendage markers of basal body and Rpgrip1l at the TZ. (A) Dzip1l localizes to the mother centriole in the cell. Wt and Dzip1l mutant pMEFs were immunostained for Dzip1l and acetylated α- and γ-tubulins (axoneme and centriolar markers, respectively). Dzip1l staining is positive in both ciliated and nonciliated wt mother centrioles, but not in mutant cells. Insets show negative Dzip1l staining in the centrioles indicated by arrowheads. Arrows point to cilia, and arrowheads indicate centrioles or Dzip1l staining. (B) The localization of overexpressed FS-Dzip1l recapitulates that of endogenous Dzip1l. NIH3T3 and NIH3T3-FS-Dzip1l stable cells were co-immunostained with Arl13b (labeling axoneme) and FLAG (for FS-Dzip1l) antibodies. (C) NIH3T3-FS-Dzip1l stable cells were co-immunostained for the indicated proteins and FS-Dzip1l (using FLAG antibody). Note the overlapping localization in yellow.

To determine the more precise localization of Dzip1l at mother centrioles, FS-Dzip1l localization relative to several known mother centriolar proteins was examined. FS-Dzip1l localization overlapped fully with that of Dzip1 and partially with that of the distal appendage marker Cep164 (Graser et al., 2007), subdistal appendage proteins Odf2 (Ishikawa et al., 2005; Tateishi et al., 2013) and ninein (Mogensen et al., 2000), centrosomal protein Cep290 (Chang et al., 2006; Sayer et al., 2006; Valente et al., 2006) and TZ protein Rpgrip1l (Arts et al., 2007; Delous et al., 2007; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Gerhardt et al., 2015; Mahuzier et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2017; Vierkotten et al., 2007), but not with Ofd1 at the distal end of mother centriole (Singla et al., 2010) (Fig. 4C). Thus, Dzip1l is an appendage and/or TZ protein.

Dzip1l interacts with Cby and controls Cby centriolar localization

To elucidate the mechanism by which Dzip1l regulates ciliogenesis and function, we sought to identify Dzip1l-interacting proteins. To this end, a FS-Dzip1l-NIH3T3 stable cell line was used to perform immunoaffinity purification using FLAG antibody beads, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were then subject to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. One of the co-immunoprecipitated proteins was Cby, a known distal appendage protein associated with ciliogenesis (Burke et al., 2014; Steere et al., 2012), given that there were six identified peptide sequences [peptide spectrum matches (PSM)=4] for the protein (Table S1). The Dzip1l–Cby interaction was verified by co-immunoprecipitation using proteins overexpressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, Cby also interacted with Dzip1 (Fig. 5B), which also interacted with Dzip1l (Fig. 5C). Thus, Dzip1l, Dzip1 and Cby form a protein complex.

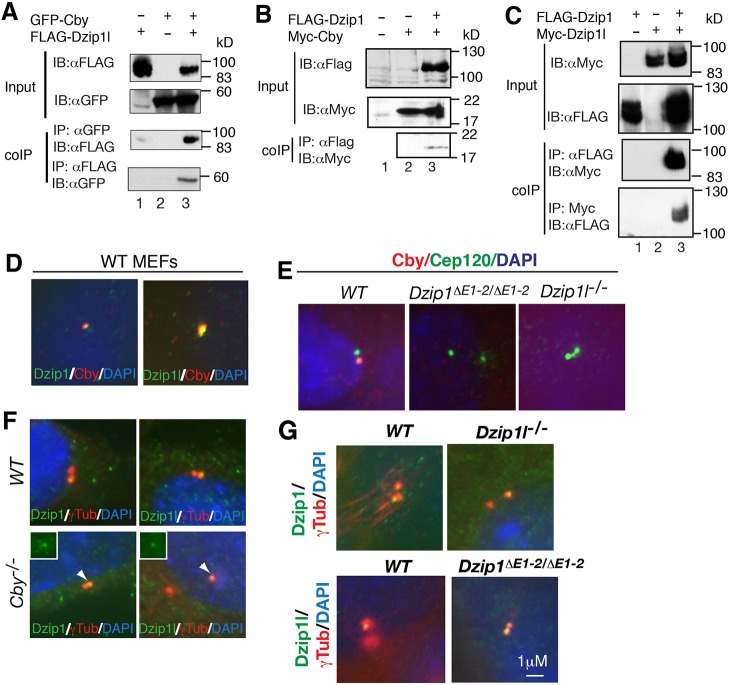

Fig. 5.

Dzip1l and Dzip1 interact and colocalize with Cby and control its localization to the basal body. (A-C) Co-immunoprecipitation shows that Dzip1l (A) and Dzip1 (B) interact with Cby and each other (C) (n=2 experiments). FLAG and Myc, epitope tags; coIP, co-immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot. (D-G) Wt, Cby, Dzip1 and Dzip1l mutant MEFs were subject to immunostaining for the indicated proteins (in color) and DAPI (for nuclei). The results show that Dzip1l and Dzip1 colocalize with Cby (D), that Cby localization is dependent on Dzip1 or Dzip1l (E), but the centriolar localization of Dzip1 and Dzip1l is independent of Cby (F) or each other (G) (n≥2 experiments). Insets (F) show Dzip1 and Dzip1L staining.

To determine the significance of the interaction, we asked whether Dzip1l, Dzip1 and Cby colocalize at the mother centriole and that, if they do, whether their localization is dependent on one another. Immunofluorescence showed that both Dzip1 and Dzip1l colocalized with Cby (Fig. 5D). Cby failed to localize to the mother centriole in either Dzip1 or Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 5E). By contrast, the mother centriolar localization of either Dzip1 or Dzip1l was not affected by loss of Cby (Fig. 5F). Similarly, the centriolar localization of Dzip1 did not depend on that of Dzip1l, and vice versa (Fig. 5G). Thus, Cby centriolar localization is dependent on either Dzip1 or Dzip1l, but the mother centriolar localization of Dzip1 and Dzip1l is independent of Cby and each other.

Dzip1l interacts genetically with Cby in neural tube patterning and Bromi in both ciliogenesis and neural tube patterning

Given the physical interaction between Dzip1l and Cby, we next wanted to determine the relationship between the two in ciliogenesis. Immunostaining for the ciliary markers Arl13b and acetylated α-tubulin showed that the number of cilia on neuroepithelia of Dzip1l mutant neural tube and limb mesenchymal cells was approximately half that in wt. Cilia number on both cell types in Cby mutant embryos was comparable to that in wt, whereas cilia number in Dzip1l;Cby double mutants was similar to that in Dzip1l single mutants (Fig. 6A). Thus, given that the mother centriolar localization of Cby is dependent on Dzip1l (Fig. 5E), these data indicate that Dzip1l functions upstream of Cby in ciliogenesis.

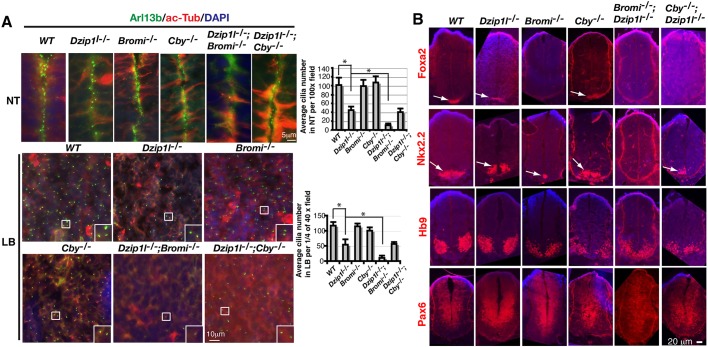

Fig. 6.

Dzip1l genetically interacts with Cby in neural tube patterning and Bromi in both ciliogenesis and neural tube patterning. (A) Neural tube (NT) and limb bud (LB) sections of E10.5 embryos with indicated genotypes were immunostained for Arl13b and acetylated α-tubulin (ac-Tub), two cilia markers. Graphs to the right show average cilia number on neuroepithelia of NT per field under a 100× lens (n≥5 sections from two embryos for each genotype) or in LB per 1/4 field under a 40× lens (n≥4 sections from two embryos for each genotype). *P≤0.0042, two-tailed Student's t-test. Insets are enlargements of the boxed areas. (B) Neural tube sections of E10.5 embryos with indicated genotypes were immunostained for neuronal markers and counterstained with DAPI (blue) (n≥4 sections from two embryos for each genotype). Arrows point to specific staining for Foxa2 and Nkx2.2. Note that the residual Nkx2.2+ domain is seen only in Bromi−/− but not Bromi−/−;Dzip1l−/− neural tubes and that only the residual Nkx2.2+ domain, rather than both Foxa2+ and Nkx2.2+ domains in Cby−/−, is observed in Cby−/−;Dzip1l−/− neural tubes.

We were also curious about the genetic interaction of Dzip1l and Cby in terms of neural tube patterning. All the ventral cell types examined in the neural tube, including the floor plate (Foxa2+ cells), Nkx2.2+ p3 interneuron progenitors and Hb9+ motoneurons, appeared to be specified and patterned normally in either Dzip1l or Cby single mutants. Consistent with this, the dorsal marker Pax6 was ventrally restricted. However, unlike in single mutants, the floor plate was missing in Dzip1l;Cby double mutants. Consequently, Nkx2.2+ p3 interneuron progenitors, although specified, were shifted to the most ventral region of the neural tube (Fig. 6B). Thus, Dzip1l and Cby have overlapping functions in neural tube patterning.

A previous study showed that cilia were swollen in Bromi mutants, although cilia number was normal (Ko et al., 2010). Given that some cilia are bulged in Dzip1l mutants (Fig. 2B), we wondered whether Dzip1l and Bromi have an overlapping function in ciliogenesis. A Bromi mutant mouse line was created using a targeted gene knockout approach to delete exons 6-8. As predicted, the homozygous Bromi mutant embryos died at mid-gestation and displayed exencephaly (Fig. S2). Some cilia were bulged in the Bromi mutants (see below), but the cilia density on the neuroepithelia of the neural tube and limb bud mesenchymal cells was similar to that in wt. Interestingly, however, when Bromi mutants were crossed with Dzip1l mutants to generate Bromi;Dzip1l double mutants, cilia were scarce in both tissues of the double-mutant embryos (Fig. 6A), indicating that Dzip1l and Bromi have overlapping functions in ciliogenesis.

We also compared neural tube patterning between Dzip1l and Bromi single and double mutants. As shown in Fig. 1E and Fig. 6B, neural tube patterning was unaffected in Dzip1l mutants. The floor plate marked by Foxa2 expression was missing in Bromi mutants and, consequently, Nkx2.2+ p3 neural progenitors were ventrally shifted in the neural tube. This is consistent with a previous report (Ko et al., 2010). However, both the floor plate and Nkx2.2+ p3 neural progenitors were not specified in Dzip1l;Bromi double mutants. As a result, Hb9+ motoneuron domains shifted ventrally. Consistently, unlike that in wt, Dzip1l or Bromi single mutants, the dorsal marker Pax6 was expressed throughout the neural tube in Dzip1l;Bromi double mutants (Fig. 6B). Thus, as in ciliogenesis, Dzip1l and Bromi also have redundant roles in neural tube patterning.

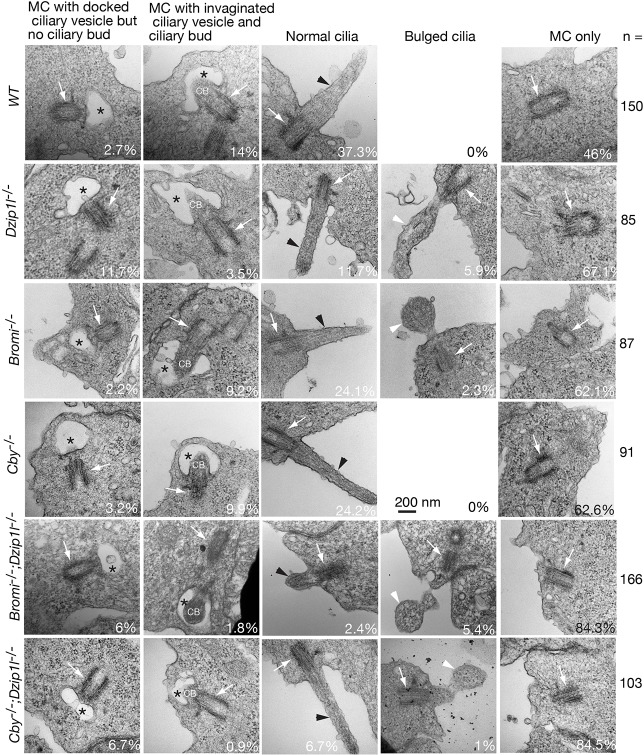

Ciliary bud formation is compromised in Dzip1l mutants

To pinpoint which step in ciliogenesis is affected by Dzip1l mutation, we examined the ultrastructure of cilia on neuroepithelia in the neural tube of wt, Dzip1l, Bromi, Cby, Bromi;Dzip1l, and Cby;Dzip1l mutant embryos by TEM. To objectively obtain data, all mother centrioles that were observed from ∼15 embryo sections were imaged, and ∼100 or more images were taken for each genotype. The images were classified into five categories according to the ciliary state and morphology: (1) mother centrioles only; (2) mother centrioles with docked ciliary vesicle but no ciliary bud; (3) mother centrioles with invaginated ciliary vesicle and ciliary bud or axoneme; (4) cilia (mother centrioles with axoneme exposed to the extracellular space); and (5) bulged cilia (Fig. 7). In wt, on average, there were 2.7% mother centrioles with docked vesicle but no ciliary bud and 14% mother centrioles with invaginated ciliary vesicle and ciliary bud. Similar percentages in these two categories were observed in Bromi (2.2% and 9.2%, respectively) or Cby (3.2% and 9.9%, respectively) single mutants. By contrast, mother centrioles in these two categories were 11.7% and 3.5% in Dzip1l mutants, 6% and 1.8% in Bromi;Dzip1l mutants, and 6.7% and 0.9% in Cby;Dzip1l mutants, respectively. These results suggest that Dzip1l, but not Bromi or Cby, promotes ciliary bud formation. In addition, the sum of the number of mother centrioles in these two categories in either Bromi;Dzip1l or Cby;Dzip1l double mutants (7.8% or 7.6%, respectively) was markedly lower than in wt, Dizip1l, Bromi or Cby single mutants (16.7%, 15.2%, 11.4% and 13.1%, respectively). This suggests that Dzip1l and Bromi or Cby act together to regulate ciliogenesis at a step before the docking of ciliary vesicle to the basal body.

Fig. 7.

Ciliary bud formation is compromised and cilia are bulged in Dzip1l mutants. Shown are TEM micrographs of cilia on neuroepithelia in the neural tube of E10.5 embryos with indicated genotypes. Mother centrioles (MC) are indicated by arrows, cilia by black arrowheads, bulged cilia by arrowheads, and ciliary vesicles by asterisks. CB, ciliary bud. The percentages of mother centrioles in each category and total number of images are listed. Images for wt and Bromi−/−;Dzip1l−/− are from two separate experiments and the rest from one experiment.

The other obvious difference between wt and Dzip1l mutants was the cilia morphology. In wt, all the cilia, which accounted for 37.3% of the total basal bodies detected by TEM, were normal. By contrast, only 11.7% of mother centrioles formed normal-looking cilia, whereas 5.9% had bulged cilia in Dzip1l mutants. Bulged cilia (2.3%) were also observed in Bromi, but not Cby, mutants (Fig. 7 and Fig. S3). This number in Bromi;Dzip1l and Cby;Dzip1l mutants was 5.4% and 1%, respectively, which is similar to, or lower than, that in Dzip1l mutants, respectively. However, because the percentage of normal cilia was also lower in Bromi;Dzip1l or Cby;Dzip1l double mutants (2.4% and 6.7%, respectively), either a decrease or no increase in the number of bulged cilia in Bromi;Dzip1l or Cby;Dzip1l mutants was likely the result of an overall decrease in cilia formation in the double mutants. Therefore, Dzip1l and Bromi function together to support normal cilia formation.

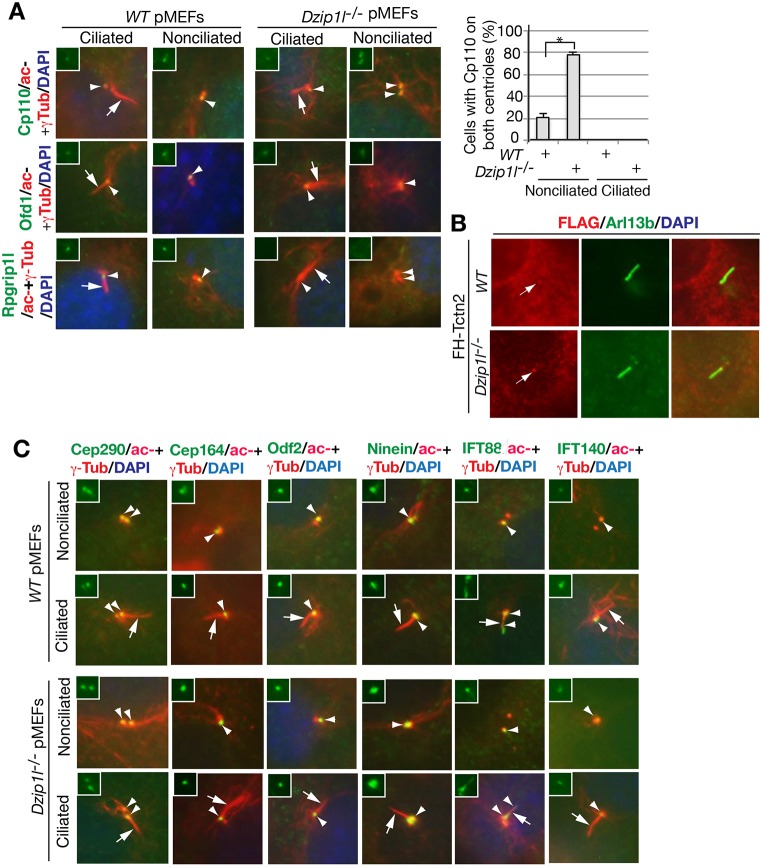

Dzip1l is required for the removal of Cp110 from, and recruitment of Rpgrip1l to, the mother centriole

Compromised ciliary bud formation in Dzip1l mutants suggests that Dzip1l is required for an early step in ciliogenesis. Overexpression and RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown studies in cultured cells showed that Cp110 inhibits ciliogenesis by capping the mother centriole and that the removal of Cp110 from the distal end of mother centrioles is an essential step for the initiation of ciliogenesis (Schmidt et al., 2009; Spektor et al., 2007). However, a recent in vivo study demonstrated that Cp110 mutation results in loss of cilia in mice (Yadav et al., 2016). Thus, Cp110 plays both negative and positive roles in ciliogenesis. To understand how loss of Dzip1l might result in a defect in ciliary bud formation, Cp110 localization at centrioles was examined in wt and Dzip1l mutant cells. Cp110 staining was detected only at one of two centrioles in most nonciliated and all ciliated wt pMEFs. By contrast, Cp110 signals were seen at both centrioles in ∼80% of nonciliated Dzip1l mutant pMEFs, although only one centriole was Cp110 positive in ciliated mutant cells. This was specific for Cp110, because the localization of Ofd1 to the distal end of the mother centriole (Singla et al., 2010) was unaffected in Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 8A). Together, these results suggest that the basal body protein composition that is required for a specific early process of ciliogenesis is disrupted in Dzip1l mutant cells.

Fig. 8.

Dzip1l mutant cells fail to remove Cp110 from the mother centriole and to recruit Rpgrip1l to the mother centriole. (A) wt and Dzip1l mutant pMEFs were stained for the indicated proteins. The graph to the right shows the percentage of cells with Cp110 on both centrioles (n≥95). *P=0.0095, two-tailed Student's t-test. Note that Cp110 is not removed from the mother centriole and that Rpgrip1l is absent at the mother centriole. (B) Tctn2 localizes to the transition zone in Dzip1l mutant cells. Wt and Dzip1l mutant cells were transduced with murine retrovirus carrying FH-Tctn2 construct and then stained with FLAG (labeling FH-Tctn2) and Arl13b (a cilia marker) antibodies. Arrows point to FH-Tctn2 staining near the proximal end of cilia, presumably the TZ. FH, FLAG and HA double tags. (C) The localization of appendage proteins and recruitment of IFT proteins to mother centrioles are unaffected in Dzip1l mutant cells. Wt and Dzip1l mutant cells were stained for the indicated proteins and nuclei by DAPI. For both A and C, arrows point to cilia, and arrowheads indicate one or both centrioles. Insets show green staining for the indicated proteins at centrioles.

The TZ is immediately adjacent to the distal end of mother centrioles. It begins to form after the docking of a ciliary vesicle to the distal appendage of a mother centriole and serves as the base for ciliary bud formation (Garcia-Gonzalo and Reiter, 2017). Thus, we wondered whether loss of Dzip1l alters the integrity of the TZ. To this end, the subcellular localization of Rpgrip1l and Tctn2, two TZ proteins (Arts et al., 2007; Delous et al., 2007; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Gerhardt et al., 2015; Mahuzier et al., 2012; Sang et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2017; Vierkotten et al., 2007), was examined. Immunostaining showed that Rpgrip1l was recruited to the mother centriole in both ciliated and nonciliated wt pMEFs, but not in nonciliated mutant cells, although it was in two out of the 35 ciliated mutant cells examined. Unlike Rpgrip1l, Tctn2 recruited to the TZ in Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 8A,B). Together, these results indicate that the integrity of the TZ is disrupted in Dzip1l mutant cells.

Given that Dzip1l centriolar localization partially overlaps with that of the Cep164, Odf2 and ninein appendage proteins and centrosomal protein Cep290 (Fig. 3C), we wondered whether the centrosomal localization of these proteins was affected in Dzip1l mutant cells. Immunostaining results showed that the centriolar localization of none of these proteins was disrupted (Fig. 8C) in both ciliated and nonciliated mutant cells. This was consistent with our TEM result: the docking of ciliary vesicles to mother centrioles, the process that is dependent on appendages of mother centrioles, was normal in Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 7).

The recruitment of IFT complexes to the mother centriole is required for ciliary bud formation. Given that ciliary bud formation is compromised in Dzip1l mutants, the localization of IFT proteins was examined. Immunofluorescent results showed that, as in wt cells, IFT88, a subunit of IFT-B, was recruited to the mother centrioles in nonciliated mutant cells and transported to cilia in ciliated mutant cells. Similarly, IFT140, part of IFT-A complex and normally localized at the mother centriole, was also recruited to the mother centrioles in both ciliated and nonciliated Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 8C). Taken together, the above observations suggest that impaired ciliary bud formation in Dzip1l mutant cells results from the failure to remove Cp110 from the mother centriole and from the loss of TZ integrity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we showed that Dzip1l is required for Hh signaling and ciliogenesis; Dzip1l, Dzip1 and Cby form a protein complex; and Dzip1l acts upstream of Cby to regulate ciliogenesis. Dzip1l also interacts genetically with Bromi, and both have overlapping functions in ciliogenesis and neural tube patterning. We also demonstrated that Dzip1l promotes ciliary bud formation through its regulation of the removal of Cp110 from the distal end of the mother centriole and the maintenance of TZ integrity. Thus, our study provides insights into the mechanism by which Dzip1l regulates ciliary biogenesis and function.

One of the hallmarks of ciliary gene mutations is the effect on Hh signaling. So far, all known cilia-related proteins regulate Hh signaling between Smo and Gli2/Gli3 (Bangs and Anderson, 2017). As a result, ciliary gene mutations often affect neural tube and limb patterning, both of which are dependent on Hh signaling. Given that most ciliary gene mutations result in only one extra digit and the phenotype for some is not completely penetrant, the effect of most known ciliary gene mutations on limb patterning appears to be modest. On the one hand, Dzip1l mutant mice exhibit 6-8 digits in forelimbs and hind limbs with complete penetrance even in a largely Swiss Webster (SW) outbred genetic background. On the other hand, the neural tube patterning of Dzip1l mutant embryos appears to be normal (Fig. 1C,D). Given that neural tube patterning relies more on Gli2 activator function, whereas limb patterning is mostly dependent on Gli3 repressor activity, these results suggest that Dzip1l mutation mostly affects Gli3 function. This regulation occurs at a level upstream of Sufu, because Dzip1l;Sufu double-mutant embryo phenotypes, including Gli3 protein stability, are similar to those of Sufu single mutants (Fig. 1H,I).

Although the effect of Dzip1l mutation on neural tube patterning, on the basis of the specification of neuronal makers, appears to be subtle, its impact on Hh signaling is clear. First, Gli2FL is stabilized and Gli3 processing is reduced in Dzip1l mutant embryos. Second, Dzip1l mutant cells fail to respond to SAG stimulation on the basis of failure in the upregulation of Gli1 and Ptch1 RNA expression (Fig. 1F) and Gli2/Gli3 accumulation in cilia (Fig. 3). Third, Dzip1l mutants exhibit expanded brain size, cleft lip and smaller nasal structures (Fig. 1C, data not shown). These data suggest that Hh signaling defects are the cause of Dzip1l mutant embryonic lethality.

Defects in ciliary biogenesis and function affect not only Hh signaling, but also other signaling pathways, including Wnt (May-Simera and Kelley, 2012). Wnt signaling has been shown to antagonize Hh signaling through activation of Gli3 transcription to regulate neural tube patterning (Yu et al., 2008). Given that a lack of cilia can potentiate canonical Wnt signaling (Lancaster et al., 2011), it is possible that Wnt signaling is increased in the Dzip1l mutant neural tube. In principle, this could lead to upregulation of Gli3 RNA transcription. In addition, because Gli3 processing is reduced in Dzip1l mutants, which increases the Gli3FL:Gli3Rep ratio (Fig. 1G), an increase in Gli3 RNA levels could increase Gli3FL levels, which may compensate the reduced Gli2FL/Gli3FL activity caused by the reduced cilia number in theDzip1l mutant neural tube. This may in part explain why no obvious neural tube patterning defect is detected in Dzip1l mutants. Additional studies are needed to determine whether this is the case.

In addition to polydactyly, Dzip1l mutant embryos also exhibit enlarged brain, cleft lip and reduced nasal structures (Fig. 1C, and data not shown). These phenotypes are similar to those found in another Dzip1l mutant that was recently reported (Lu et al., 2017). At least the enlarged brain phenotype is likely the result of the increased Gli3FL:Gli3Rep ratio, because we have previously shown that experimentally increasing the Gli3FL:Gli3Rep ratio can result in increased cerebral cortical size, a phenotype that resembles that of the Kif3a mutant, in which ciliogenesis and function are disrupted (Wilson et al., 2012). In addition to Hh signaling, Wnt signaling might also be involved in expanded cerebral cortex of Dzip1l mutants, because Wnt signaling was shown to be elevated in a hypomorphic Ift88 mutant mouse line (Willaredt et al., 2008). Further studies are necessary to determine whether this is the case.

Dzip1l localizes to the mother centriole (Glazer et al., 2010), and its localization partially overlaps with the basal body appendage proteins Cep164, Odf2, ninein and Rpgrip1l at the TZ, but not Ofd1, a protein at the distal end of the mother centriole (Fig. 4). This is in agreement with a recent report showing that Dzip1l localizes to the TZ (Lu et al., 2017). Consistent with its localization, the number of cilia in Dzip1l mutants is approximately half that in wt and even lower in mutant pMEFs (on average, ∼3.2%) (Fig. 2A). This differs from a recent study showing that cilia number in Dzip1l mutant tissues was largely unaffected and that ∼30% Dzip1l mutant pMEFs were ciliated (Lu et al., 2017). The difference in cilia number between the two studies is most likely attributed to the different mutant alleles used, because the Dzip1l mutants in the present study would produce an N-terminal 195 aa fragment, if any (Fig. 1A), whereas the Dzip1lspy mutants in Lu et al. (2017) would express an N-terminal 375 aa peptide. The genetic background is unlikely to contribute to the difference, because the Dzip1l mutant allele in our study is mostly in a SW outbred background.

In cultured cells, the formation of primary cilia begins with the docking of the ciliary vesicle onto the basal body (Schmidt et al., 2012; Sorokin, 1962; Tanos et al., 2013), followed by the removal of Cp110 from the distal end of the basal body (Spektor et al., 2007), the recruitment of IFT components (Pazour et al., 2000; Qin et al., 2004; Rosenbaum and Witman, 2002), the assembly of the TZ (Chih et al., 2011; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2011), the invagination of the ciliary vesicle by the ciliary bud and then cilia, and, finally, fusion of the ciliary vesicle with the plasma membrane to expose cilia to the extracellular space (Garcia-Gonzalo and Reiter, 2017; Pedersen and Rosenbaum, 2008). Disruption of any of these processes may result in defects in ciliogenesis, and the type of defect in ciliary structure may indicate which process in ciliogenesis is disrupted. TEM analysis of neuroepithelia of Dzip1l mutant neural tube revealed that there was a large number of basal bodies docked with the ciliary vesicle but no ciliary bud (11.7% in the mutant versus 2.7% in wt) and a smaller number of basal bodies with invaginated ciliary vesicle and ciliary bud (3.5% in the mutant versus 14% in wt) (Fig. 7). These results indicate that ciliary bud formation is compromised in Dzip1l mutants. A similar defect was also observed in igu mutant zebrafish, although the molecular mechanism was unknown (Tay et al., 2010). Thus, Dzip1l and Igu most likely use the same mechanism to regulate ciliogenesis.

In support of the TEM results, the capping protein Cp110 was not removed from the distal end of the mother centriole in most of nonciliated Dzip1l mutant cells, and Rpgrip1l was not recruited to the TZ in Dzip1l mutant cells (Fig. 8A). These results indicate that Dzip1l is required for the integrity of the TZ, which serves as the base for ciliary bud formation (Garcia-Gonzalo and Reiter, 2017). A recent study showed that Cep162 RNAi knockdown arrested ciliogenesis at the stage of TZ assembly (Wang et al., 2012). In Cep162 RNAi knockdown RPE1 cells, Rpgrip1l was also absent at the TZ, but Cp110 was removed from the distal end of the mother centriole. Thus, Dzip1l and Cep162 most likely regulate different processes in the assembly and/or maintenance of the TZ.

Cby is required for ciliogenesis in cultured cells and facilitates basal body docking to the apical cell membrane during airway cell differentiation (Burke et al., 2014; Steere et al., 2012). In the present study, we showed that Dzip1l, Dzip1 and Cby form a protein complex (Fig. 5A-C). The localization of Cby to the appendages of the mother centriole is dependent on either Dzip1l or Dzip1, whereas Dzip1l and Dzip1 do not depend on Cby (Fig. 5D-F). The number of cilia on neuroepithelia in the neural tube and limb mesenchymal cells of Cby mutant embryos was similar to that in wt, but the number in Dzip1l;Cby double mutants was comparable to that in Dzip1l mutants (Fig. 6). In addition, the percentage of basal bodies docked with the vesicle but with no ciliary bud in Dzip1l;Cby double mutant neural tubes was not increase compared with that in Dzip1l mutants (Fig. 7). There was a difference in the number of cilia counted by immunofluorescence versus TEM (Figs 6 and 7). This discrepancy is likely due to two reasons. First, the number of cilia determined by TEM is likely undercounted because only fully extended axonemes are counted as cilia, whereas both partially and fully extended axonemes are included by immunofluorescence, because both types of axonemes are stained. Second, the number of cilia determined by TEM may have a larger experimental error than that determined by immunofluorescence, because the sample size was smaller. Thus, together, these results indicate that Dzip1l acts upstream of Cby to regulate ciliogenesis. By contrast, Dzip1l and Cby appear to have an overlapping function in neural tube patterning, because the floor plate is absent in the double mutants but present in either single mutant (Fig. 6B).

The finding that Dzip1l is required for ciliary bud formation is in line with the model that Cby functions in ciliary vesicle formation through vesicle trafficking or fusion (Burke et al., 2014). In fly spermatogenesis, Cby, in cooperation with Azi1, has been shown to facilitate TZ assembly via the formation of ciliary vesicles (Vieillard et al., 2016). Thus, given that Dzip1l interacts with Cby, Dzip1l may also act in the trafficking or fusion of vesicles via Cby.

In addition to a high number of basal bodies with docked vesicles but no ciliary bud in Dzip1l mutants, the other defect was a high percentage of bulged cilia. A similar ciliary morphology is also found in Bromi mutants, although cilia number appears to be normal (Fig. 6A, Fig. 7 and Fig. S3) (Ko et al., 2010). Interestingly, cilia were scarce, and the neural tube patterning defect was also exacerbated in Dzip1l;Bromi double mutants (Fig. 6). The results indicate that Dzip1l and Bromi have a redundant function in both ciliogenesis and neural tube patterning. Given that IFT proteins are recruited to basal bodies in Dzip1l and Bromi mutant cells (Fig. 8C), the dysmorphic cilia seen in Dzip1l and Bromi mutants are probably the result of inefficient anterograde and/or retrograde IFT trafficking. Consistent with this, both Gli2 and Gli3 (and probably Smo as well) accumulate in Dzip1l mutant cilia compared with wt in the absence of Hh signaling (Fig. 3). A recent study showed that the loss of Ccrk (Cdk20), a Bromi-interacting protein, results in bulged cilia and imbalanced IFT trafficking. However, Ccrk mutation does not lead to Gli2 and Gli3 accumulation in cilia (Snouffer et al., 2017). Thus, Dzip1l and Ccrk most likely regulate different steps of IFT trafficking. Additional experiments are needed to determine whether this is the case.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains and the generation of a Dzip1l mutant allele

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Weill Cornell Medical College approved this research, including the use of mice and MEFs.

A BAC clone containing mouse Dzip1l genomic DNA sequences was purchased from the BACPAC Resources Center and used to create a Dzip1l-targeting construct. The construct was engineered by replacing 4-6 exons of the Dzip1l gene with the neomycin cassette flanked by loxP sites (Fig. 1A). The linearized construct was electroporated into W4 embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and targeted ESC clones were identified by digestion of genomic DNA with EcoRI, followed by a Southern blot analysis of ESC DNA using a probe as indicated (Fig. 1B). Two Dzip1l-targeted ESC clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate chimeric founders, which were then bred with C57BL/6 to establish F1 heterozygotes. The Dzip1l heterozygotes were then bred with SW outbred mice and maintained in a SW background. PCR analysis was used for routine genotyping with the following primers: forward primer BW1199F, 5′-CTATGCCTGGAGTTATAGGCAG-3′ and reverse primer BW1172R, 5′-ACTGCCCTAAGAACACATGTC -3′ for the wt allele, which produced a 140 bp fragment; and forward primer BW1199F and reverse primer CW649-loxpR, 5′-CGAAGTTATATTAAGGGTTCCG-3′ for the targeted Dzip1l allele, which produced a 100 bp fragment. Sufu and Cby mutants were described previously (Voronina et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010) and also maintained in a SW background.

Cell lines and cell culture

Wt and mutant Dzip1l pMEFs were prepared from E13.5 or E14.5 mouse embryos and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin. Dzip1 mutant MEFs (Wang et al., 2013) and HEK293 cells were grown in the same medium.

NIH3T3 and NIH3T3-FS-Dzip1l stable cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum (CS), penicillin and streptomycin. The stable cell line was established by transducing NIH3T3 cells with murine retrovirus carrying the FS-Dzip1l construct and then selecting neomycin-resistant clones with G418 (1 mg/ml) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). HEK293 was purchased from ATCC and NIH3T3 was obtained from the Xin-Yun Huang lab at Weill Medical College. The cells were free of contamination and authenticated by cell morphology.

cDNA constructs, cloning and transfection

Dzip1l (BC099950) and Dzip1 (BC098211) cDNAs were purchased from Open Biosystem (now part of Dharmacon). FLAG-Dzip1l, FLAG-Dzip1 and Myc-Dzip1l expression constructs were created by cloning the respective cDNAs into CMV-based pRK-FLAG and pRK-Myc plasmids, or murine retroviral vector pLNCX-FS [FLAG and Strep double tags inserted in a pLNCX vector (Clontech)] by PCR and conventional recombinant DNA cloning techniques. Mouse Cby cDNA was amplified from a mouse cDNA library by PCR and cloned into pRK-Myc or pEGFP vectors (Clontech). pLNCX-FH-Tctn2 was developed as previously described (Wang et al., 2017). The constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Murine retrovirus carrying a FS-Dzip1l or FH-Tctn2 insert was generated by cotransfection of a pLNCX-FS-Dzip1l or pLNCX-FH-Tctn2 viral construct and a pEco packaging construct into Phoenix-Eco cells (ATCC) using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Wang et al., 2013).

Embryo section immunofluorescence, whole-mount lacZ staining and mouse skeleton preparation

For immunofluorescence of neural tube sections, mouse embryos at E10.5 were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS for 1 h at 4°C, equilibrated in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight at 4°C and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT). The frozen embryos were transversely cryosectioned (10 µm/section). Tissue sections were immunostained using antibodies against Foxa2 (concentrated), Nkx2.2, Hb9, Pax6 and Pax7 [Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)], or against Arl13b and acetylated α-tubulin together as described (Pan et al., 2009).

Skeleton preparation of E18.5 embryos and lacZ staining of E10.5 embryos were performed as described (Hogan et al., 1994).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

For cell ciliation studies, cells were plated on coverslips coated with 0.1% gelatin for at least overnight and serum starved with 0.1% FBS for 20-24 h to arrest the cycling of the cells. For centrosome staining, cells were fixed with −20°C cold methanol for 5 min. For both cytoplasmic and cilia staining, cells were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS for 15 min. For both centrosome and cilia staining, cells were fixed either with 4% PFA for 2 min followed by cold methanol for 5 min or with cold methanol alone. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with blocking solution (PBS/0.2% Triton X-100/2% heat-inactivated CS) for 20 min. The cells were then incubated with primary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. In other cases, the fixed cells were incubated with PBS/0.2% Triton-X100 for 5 min and then immediately with primary antibodies. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, the coverslips were mounted to glass slides with Vectashield mounting fluid with DAPI (Vector Labs). The staining was visualized using a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescent microscope.

Antibodies

Rabbits were immunized with the following insoluble His-tagged protein fragments purified from bacteria to generate Dzip1l, Rpgrip1l, Ofd1, Cp110 and ninein antibodies: Dzip1l (276-503 aa) (Syd Lab), Rpgrip1l (715-1265 aa) (Biosynthesis), Ofd1 (1-408 aa), Cp110 (1-149 aa) and ninein (1291-E aa) (Covance). Although anti-Dzip1l antibodies may detect other nonspecific proteins of the same size as Dzip1l in western blot analysis (data not shown), this antibody was also found to detect the protein in the mother centriole (Fig. 4A). Smo antibodies were made in mice using its C-terminal fragment fused with GST. Other antibodies included: Gli2, Gli3, Dzip1, Arl13b, IFT88, Cep164, Odf2, Cep290, GFP (all 1:1000) (Wang et al., 2000, 2013; Wu et al., 2014, 2017), acetylated α-tubulin (1:2000), γ-tubulin (1:4000) (T6793, T6557, Sigma), IFT40 (1:1000) (Pazour et al., 2002), Cby (1:500) (Cyge et al., 2011), rabbit Pax6 polyclonal (Covance), and Foxa2, Nkx2.2, Hb9, Pax6 and Pax7 (Developmental Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa). Secondary antibodies [Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (111-545-144) and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (115-165-146)] were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Immunoblotting, co-immunoprecipitation, immunoaffinity purification and mass spectrometry analysis

E10.5 mouse embryos used to detect Gli2 or Gli3 were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitors). Transfected HEK293 cells used for co-immunoprecipitation were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40, protease inhibitors). Immunoblotting and co-immunoprecipitation were performed as described (Wang et al., 2000).

For immunoaffinity purification, 20 15 cm plates of NIH3T3 cells stably expressing FS-Dzip1l virus or NIH3T3 control cells were lysed by Dounce homogenization in lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP40, freshly add DTT (1 mM), protease inhibitor cocktail]. After being cleared by centrifugation, the protein lysates were incubated with 200 µl FLAG antibody conjugated with Sepharose beads (A2220, Sigma) by rotation for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with lysis buffer at least four times. The immunoprecipitated proteins were denatured with SDS loading buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel lanes were sliced into eight pieces, which were subjected to digestion with trypsin. The resulting peptides were extracted and subjected to MS analysis according to a method previously described (Duan et al., 2016). The MS/MS data were searched using Proteome Discoverer 1.3 (Thermo Scientific) against the IPI protein database released in September 2011 (Kersey et al., 2004) and peptides with a 1% false discovery rate were obtained for protein identification.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy

E10.5 embryos were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4, EM quality) overnight at 4°C. For SEM, the embryos were washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and dissected to expose the lumen of the neural tube. The embryo fragments were dehydrated using a graded ethanol series and subjected to critical point drying. The embryo fragments were mounted with the lumen face up on aluminium stubs with adhesive tabs and sputter-coated with gold-palladium alloy. Cilia of neuroepithelia in the neural tube were imaged using a field emission electron microscope (Supra 25, Carl Zeiss). For TEM, after washing with sodium cacodylate buffer and then water, the fixed embryos were transversely cut into five segments. The embryos segments were incubated with 1% OsO4 for 1 h in the dark. After washing with water, the embryo segments were incubated in 1% uranyl acetate for 2 h at room temperature, washed with water and dehydrated with a series of graded ethanol. The embryo segments were then infiltrated and embedded with Embed812 mixed solution according to the manufacturer's instruction (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Transverse ultrathin sections (65 nm) were cut with Leica UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems), stained with uranyl acetate and lead nitrate, and imaged with a JEOL1400 transmission electron microscope.

RT-qPCR

Confluent wt and Dzip1l mutant pMEFs in 60 mm plates were incubated with growth medium containing SAG (300 nM) (Cayman Chemical) or vehicle control overnight. Total RNA was isolated from the pMEFs by using TRIzol solution according to the manufacturer's instruction (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five micrograms of each of the isolated total RNA were used to synthesize first stranded cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instruction (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR was performed using a qPCR kit (MasterMix-R, Applied Biological Materials) and primers described previously (Wang et al., 2017). For a 20 µl reaction, 0.15 µl of the first stranded cDNA was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Gregory Pazour for IFT140 antibodies, and Ms Nina Lampen and Leona Cohen-Gould for help with SEM and TEM. Monoclonal antibodies, Foxa2, Nkx2.2, Hb9, Pax6 and Pax7, were purchased from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, under contract NO1-HD-7-3263 from the NICHD.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.W., B.W.; Methodology: C.W., J.L., X.J., G.X., B.W.; Formal analysis: B.W.; Investigation: C.W., J.L., X.J., G.X., B.W.; Resources: K.-I.T.; Writing - original draft: B.W.; Writing - review & editing: C.W., J.L., K.-I.T., G.X., B.W.; Supervision: B.W.; Funding acquisition: B.W.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R01GM114429 to B.W., R01HL107493 to K.-I.T.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470772) and Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Translational Research and Therapy for Neuro-Psycho-Diseases (BM2013003) to G.X. J.L. is a recipient of a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.164236.supplemental

References

- Arts H. H., Doherty D., van Beersum S. E. C., Parisi M. A., Letteboer S. J. F., Gorden N. T., Peters T. A., Märker T., Voesenek K., Kartono A. et al. (2007). Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome. Nat. Genet. 39, 882-888. 10.1038/ng2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C. B., Stephen D. and Joyner A. L. (2004). All mouse ventral spinal cord patterning by hedgehog is Gli dependent and involves an activator function of Gli3. Dev. Cell 6, 103-115. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00394-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangs F. and Anderson K. V. (2017). Primary cilia and mammalian hedgehog signaling. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 9, a028175 10.1101/cshperspect.a028175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J., Pierani A., Jessell T. M. and Ericson J. (2000). A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell 101, 435-445. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80853-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M. C., Li F.-Q., Cyge B., Arashiro T., Brechbuhl H. M., Chen X., Siller S. S., Weiss M. A., O'Connell C. B., Love D. et al. (2014). Chibby promotes ciliary vesicle formation and basal body docking during airway cell differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 207, 123-137. 10.1083/jcb.201406140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B., Khanna H., Hawes N., Jimeno D., He S., Lillo C., Parapuram S. K., Cheng H., Scott A., Hurd R. E. et al. (2006). In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 1847-1857. 10.1093/hmg/ddl107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. K., Taipale J., Young K. E., Maiti T. and Beachy P. A. (2002). Small molecule modulation of Smoothened activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14071-14076. 10.1073/pnas.182542899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-H., Wilson C. W., Li Y.-J., Law K. K. L., Lu C.-S., Gacayan R., Zhang X., Hui C. C. and Chuang P.-T. (2009). Cilium-independent regulation of Gli protein function by Sufu in Hedgehog signaling is evolutionarily conserved. Genes Dev. 23, 1910-1928. 10.1101/gad.1794109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B., Liu P., Chinn Y., Chalouni C., Komuves L. G., Hass P. E., Sandoval W. and Peterson A. S. (2011). A ciliopathy complex at the transition zone protects the cilia as a privileged membrane domain. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 61-72. 10.1038/ncb2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A. F., Yu K. P., Brueckner M., Brailey L. L., Johnson L., McGrath J. M. and Bale A. E. (2005). Cardiac and CNS defects in a mouse with targeted disruption of suppressor of fused. Development 132, 4407-4417. 10.1242/dev.02021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyge B., Fischer V., Takemaru K.-I. and Li F.-Q. (2011). Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against human Chibby protein. Hybridoma 30, 163-168. 10.1089/hyb.2010.0098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delous M., Baala L., Salomon R., Laclef C., Vierkotten J., Tory K., Golzio C., Lacoste T., Besse L., Ozilou C. et al. (2007). The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 39, 875-881. 10.1038/ng2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Fukami S., Meng X., Nishizaki Y., Zhang X., Sasaki H., Dlugosz A., Nakafuku M. and Hui C. (1999). Mouse suppressor of fused is a negative regulator of sonic hedgehog signaling and alters the subcellular distribution of Gli1. Curr. Biol. 9, 1119-1122. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80482-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle W. E., Robinson J. F., Kneist A., Sirerol-Piquer M. S., Frints S. G. M., Corbit K. C., Zaghloul N. A., van Lijnschoten G., Mulders L., Verver D. E. et al. (2011). Disruption of a ciliary B9 protein complex causes Meckel syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 94-110. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W., Chen S., Zhang Y., Li D., Wang R., Chen S., Li J., Qiu X. and Xu G. (2016). Protein C-terminal enzymatic labeling identifies novel caspase cleavages during the apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells induced by kinase inhibition. Proteomics 16, 60-69. 10.1002/pmic.201500356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo F. R. and Reiter J. F. (2017). Open sesame: how transition fibers and the transition zone control ciliary composition. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 9, a028134 10.1101/cshperspect.a028134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Corbit K. C., Sirerol-Piquer M. S., Ramaswami G., Otto E. A., Noriega T. R., Seol A. D., Robinson J. F., Bennett C. L., Josifova D. J. et al. (2011). A transition zone complex regulates mammalian ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane composition. Nat. Genet. 43, 776-784. 10.1038/ng.891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J. M., Davis E. E. and Katsanis N. (2009). The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell 137, 32-45. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt C., Lier J. M., Burmuhl S., Struchtrup A., Deutschmann K., Vetter M., Leu T., Reeg S., Grune T. and Rüther U. (2015). The transition zone protein Rpgrip1l regulates proteasomal activity at the primary cilium. J. Cell Biol. 210, 115-133. 10.1083/jcb.201408060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer A. M., Wilkinson A. W., Backer C. B., Lapan S. W., Gutzman J. H., Cheeseman I. M. and Reddien P. W. (2010). The Zn finger protein Iguana impacts Hedgehog signaling by promoting ciliogenesis. Dev. Biol. 337, 148-156. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich L. V., Milenković L., Higgins K. M. and Scott M. P. (1997). Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science 277, 1109-1113. 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graser S., Stierhof Y. D., Lavoie S. B., Gassner O. S., Lamla S., Le Clech M. and Nigg E. A. (2007). Cep164, a novel centriole appendage protein required for primary cilium formation. J. Cell Biol. 179, 321-330. 10.1083/jcb.200707181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B., Beddington R., Costantini F. and Lacy E. (1994). Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Milenkovic L., Jin H., Scott M. P., Nachury M. V., Spiliotis E. T. and Nelson W. J. (2010). A septin diffusion barrier at the base of the primary cilium maintains ciliary membrane protein distribution. Science 329, 436-439. 10.1126/science.1191054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H., Kubo A., Tsukita S. and Tsukita S. (2005). Odf2-deficient mother centrioles lack distal/subdistal appendages and the ability to generate primary cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 517-524. 10.1038/ncb1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Kolterud A., Zeng H., Hoover A., Teglund S., Toftgård R. and Liu A. (2009). Suppressor of Fused inhibits mammalian Hedgehog signaling in the absence of cilia. Dev. Biol. 330, 452-460. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo K., Kim C. G., Lee M.-S., Moon H.-Y., Lee S.-H., Kim M. J., Kweon H.-S., Park W.-Y., Kim C.-H., Gleeson J. G. et al. (2013). CCDC41 is required for ciliary vesicle docking to the mother centriole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5987-5992. 10.1073/pnas.1220927110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee H. L., Dishinger J. F., Blasius T. L., Liu C.-J., Margolis B. and Verhey K. J. (2012). A size-exclusion permeability barrier and nucleoporins characterize a ciliary pore complex that regulates transport into cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 431-437. 10.1038/ncb2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P. J., Duarte J., Williams A., Karavidopoulou Y., Birney E. and Apweiler R. (2004). The International Protein Index: an integrated database for proteomics experiments. Proteomics 4, 1985-1988. 10.1002/pmic.200300721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H. W., Norman R. X., Tran J., Fuller K. P., Fukuda M. and Eggenschwiler J. T. (2010). Broad-minded links cell cycle-related kinase to cilia assembly and hedgehog signal transduction. Dev. Cell 18, 237-247. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. and Dynlacht B. D. (2011). Regulating the transition from centriole to basal body. J. Cell Biol. 193, 435-444. 10.1083/jcb.201101005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambacher N. J., Bruel A.-L., van Dam T. J. P., Szymańska K., Slaats G. G., Kuhns S., McManus G. J., Kennedy J. E., Gaff K., Wu K. M. et al. (2016). TMEM107 recruits ciliopathy proteins to subdomains of the ciliary transition zone and causes Joubert syndrome. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 122-131. 10.1038/ncb3273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster M. A., Schroth J. and Gleeson J. G. (2011). Subcellular spatial regulation of canonical Wnt signalling at the primary cilium. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 700-707. 10.1038/ncb2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. L., Sante J., Comerci C. J., Cyge B., Menezes L. F., Li F.-Q., Germino G. G., Moerner W. E., Takemaru K.-I. and Stearns T. (2014). Cby1 promotes Ahi1 recruitment to a ring-shaped domain at the centriole-cilium interface and facilitates proper cilium formation and function. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2919-2933. 10.1091/mbc.E14-02-0735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Jensen V. L., Park K., Kennedy J., Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Romani M., De Mori R., Bruel A. L., Gaillard D., Doray B. et al. (2016). MKS5 and CEP290 dependent assembly pathway of the ciliary transition zone. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002416 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Galeano M. C. R., Ott E., Kaeslin G., Kausalya P. J., Kramer C., Ortiz-Brüchle N., Hilger N., Metzis V., Hiersche M. et al. (2017). Mutations in DZIP1L, which encodes a ciliary-transition-zone protein, cause autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 1025-1034. 10.1038/ng.3871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahuzier A., Gaudé H.-M., Grampa V., Anselme I., Silbermann F., Leroux-Berger M., Delacour D., Ezan J., Montcouquiol M., Saunier S. et al. (2012). Dishevelled stabilization by the ciliopathy protein Rpgrip1l is essential for planar cell polarity. J. Cell Biol. 198, 927-940. 10.1083/jcb.201111009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May-Simera H. L. and Kelley M. W. (2012). Cilia, Wnt signaling, and the cytoskeleton. Cilia 1, 7 10.1186/2046-2530-1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen M. M., Malik A., Piel M., Bouckson-Castaing V. and Bornens M. (2000). Microtubule minus-end anchorage at centrosomal and non-centrosomal sites: the role of ninein. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3013-3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murone M., Luoh S.-M., Stone D., Li W., Gurney A., Armanini M., Grey C., Rosenthal A. and de Sauvage F. J. (2000). Gli regulation by the opposing activities of fused and suppressor of fused. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 310-312. 10.1038/35010610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E. A. and Stearns T. (2011). The centrosome cycle: centriole biogenesis, duplication and inherent asymmetries. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1154-1160. 10.1038/ncb2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Wang C. and Wang B. (2009). Phosphorylation of Gli2 by protein kinase A is required for Gli2 processing and degradation and the Sonic Hedgehog-regulated mouse development. Dev. Biol. 326, 177-189. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour G. J., Dickert B. L., Vucica Y., Seeley E. S., Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B. and Cole D. G. (2000). Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J. Cell Biol. 151, 709-718. 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour G. J., Baker S. A., Deane J. A., Cole D. G., Dickert B. L., Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B. and Besharse J. C. (2002). The intraflagellar transport protein, IFT88, is essential for vertebrate photoreceptor assembly and maintenance. J. Cell Biol. 157, 103-113. 10.1083/jcb.200107108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen L. B. and Rosenbaum J. L. (2008). Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 85, 23-61. 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H., Diener D. R., Geimer S., Cole D. G. and Rosenbaum J. L. (2004). Intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo: IFT transports flagellar precursors to the tip and turnover products to the cell body. J. Cell Biol. 164, 255-266. 10.1083/jcb.200308132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J. F. and Leroux M. R. (2017). Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 533-547. 10.1038/nrm.2017.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson E. C., Dowdle W. E., Ozanturk A., Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Li C., Halbritter J., Elkhartoufi N., Porath J. D., Cope H., Ashley-Koch A. et al. (2015). TMEM231, mutated in orofaciodigital and Meckel syndromes, organizes the ciliary transition zone. J. Cell Biol. 209, 129-142. 10.1083/jcb.201411087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J. L. and Witman G. B. (2002). Intraflagellar transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 813-825. 10.1038/nrm952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang L., Miller J. J., Corbit K. C., Giles R. H., Brauer M. J., Otto E. A., Baye L. M., Wen X., Scales S. J., Kwong M. et al. (2011). Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell 145, 513-528. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer J. A., Otto E. A., O'Toole J. F., Nurnberg G., Kennedy M. A., Becker C., Hennies H. C., Helou J., Attanasio M., Fausett B. V. et al. (2006). The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat. Genet. 38, 674-681. 10.1038/ng1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T. I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Lavoie S. B., Stierhof Y. D. and Nigg E. A. (2009). Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19, 1005-1011. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K. N., Kuhns S., Neuner A., Hub B., Zentgraf H. and Pereira G. (2012). Cep164 mediates vesicular docking to the mother centriole during early steps of ciliogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 199, 1083-1101. 10.1083/jcb.201202126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimizu K., Nishioka N., Sasaki H., Takeda H., Karlstrom R. O. and Kawakami A. (2004). The zebrafish iguana locus encodes Dzip1, a novel zinc-finger protein required for proper regulation of Hedgehog signaling. Development 131, 2521-2532. 10.1242/dev.01059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Garcia G. III, Van De Weghe J. C., McGorty R., Pazour G. J., Doherty D., Huang B. and Reiter J. F. (2017). Super-resolution microscopy reveals that disruption of ciliary transition-zone architecture causes Joubert syndrome. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1178-1188. 10.1038/ncb3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shylo N. A., Christopher K. J., Iglesias A., Daluiski A. and Weatherbee S. D. (2016). TMEM107 is a critical regulator of ciliary protein composition and is mutated in orofaciodigital syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 37, 155-159. 10.1002/humu.22925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla V., Romaguera-Ros M., Garcia-Verdugo J. M. and Reiter J. F. (2010). Ofd1, a human disease gene, regulates the length and distal structure of centrioles. Dev. Cell 18, 410-424. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snouffer A., Brown D., Lee H., Walsh J., Lupu F., Norman R., Lechtreck K., Ko H. W. and Eggenschwiler J. (2017). Cell Cycle-Related Kinase (CCRK) regulates ciliogenesis and Hedgehog signaling in mice. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006912 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin S. (1962). Centrioles and the formation of rudimentary cilia by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 15, 363-377. 10.1083/jcb.15.2.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spektor A., Tsang W. Y., Khoo D. and Dynlacht B. D. (2007). Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell 130, 678-690. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere N., Chae V., Burke M., Li F.-Q., Takemaru K.-I. and Kuriyama R. (2012). A Wnt/beta-catenin pathway antagonist Chibby binds Cenexin at the distal end of mother centrioles and functions in primary cilia formation. PLoS ONE 7, e41077 10.1371/journal.pone.0041077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svärd J., Heby-Henricson K., Persson-Lek M., Rozell B., Lauth M., Bergstrom A., Ericson J., Toftgard R. and Teglund S. (2006). Genetic elimination of Suppressor of fused reveals an essential repressor function in the mammalian Hedgehog signaling pathway. Dev. Cell 10, 187-197. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanos B. E., Yang H.-J., Soni R., Wang W.-J., Macaluso F. P., Asara J. M. and Tsou M.- F. B. (2013). Centriole distal appendages promote membrane docking, leading to cilia initiation. Genes Dev. 27, 163-168. 10.1101/gad.207043.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi K., Yamazaki Y., Nishida T., Watanabe S., Kunimoto K., Ishikawa H. and Tsukita S. (2013). Two appendages homologous between basal bodies and centrioles are formed using distinct Odf2 domains. J. Cell Biol. 203, 417-425. 10.1083/jcb.201303071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S. Y., Yu X., Wong K. N., Panse P., Ng C. P. and Roy S. (2010). The iguana/DZIP1 protein is a novel component of the ciliogenic pathway essential for axonemal biogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 239, 527-534. 10.1002/dvdy.22199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente E. M., Silhavy J. L., Brancati F., Barrano G., Krishnaswami S. R., Castori M., Lancaster M. A., Boltshauser E., Boccone L., Al-Gazali L. et al. (2006). Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat. Genet. 38, 623-625. 10.1038/ng1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieillard J., Paschaki M., Duteyrat J.-L., Augière C., Cortier E., Lapart J.-A., Thomas J. and Durand B. (2016). Transition zone assembly and its contribution to axoneme formation in Drosophila male germ cells. J. Cell Biol. 214, 875-889. 10.1083/jcb.201603086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]