Abstract

Many important behaviours are socially learned. For example, the acoustic structure of courtship songs in songbirds is learned by listening to and interacting with conspecifics during a sensitive period in development. Signallers modify the spectral and temporal structures of their vocalizations depending on the social context, but the degree to which this modulation requires imitative social learning remains unknown. We found that male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) that were not exposed to context-dependent song modulations throughout development significantly modulated their song in ways that were typical of socially reared birds. Furthermore, the extent of these modulations was not significantly different between finches that could or could not observe these modulations during tutoring. These data suggest that this form of vocal flexibility develops without imitative social learning in male zebra finches.

Keywords: courtship, songbird, zebra finch, vocal control, behavioural development, vocal flexibility

1. Introduction

Many important behaviours, including predator evasion, mate choice, foraging, tool use and communication, are socially learned [1–4]. Numerous vertebrate species require imitative social learning during development to know how and when to produce communication signals [2–6]. As such, developmental social learning plays an important role in sculpting the behavioural control of individuals.

Social animals often ‘optimize’ their behaviours by tailoring them to their social environment [7]. For example, in songbirds like the zebra finch, Taeniopygia guttata, males modulate the spectral and temporal structures of their songs when they sing to females relative to when they sing by themselves [8,9], and these acoustic changes can increase the attractiveness of a male's song [10]. Despite the importance of these context-dependent modifications, the contribution of social learning to this behavioural modulation remains unknown.

We analysed the extent to which adult zebra finches that were raised with limited social experiences modulated their song across social contexts. We specifically asked whether juvenile zebra finches need to observe an adult modulate his song across social contexts during tutoring to produce the modulations himself. Normally raised male zebra finches sing longer, faster and more stereotyped songs when singing towards females during courtship interactions (female-directed (FD) songs) than when producing spontaneous songs not towards a particular individual or when alone (undirected (UD) songs) [11,12]. While socially isolated males have been shown to produce courtship songs, it remains unknown whether they alter their song structure across contexts [13]. Because socially reared juveniles have ample opportunity to observe and hear adult males socially modulate their song and because developmental experiences affect female preference for socially modulated song in zebra finches [14], we predicted that context-dependent vocal flexibility could be learned during development by observing adult males.

2. Material and methods

Male zebra finches were bred and raised in sound-attenuating chambers (TRA Acoustics, Ontario) and raised by both parents for only 5 days. Thereafter, fathers were removed and juvenile males were raised only by their biological mothers. Once juveniles were nutritionally independent (beyond 35 days post-hatch (dph)), they were individually housed in sound-attenuating chambers until they were sexually mature (120 dph; ‘singly reared males’). Importantly, these juveniles could not hear or observe adult males modulate the structure of their song during the sensitive period for song learning [5].

Singly reared juvenile males were tutored using an operant paradigm [15]. Briefly, juveniles heard a synthesized version of song after hopping on a perch. Zebra finches were tutored because birds deprived of song exposure throughout development produce aberrant songs that are not typical of conspecific song [16] and because tutoring juveniles allowed us to analyse the modulation of the same song features as previously examined in socially reared birds [11]. Furthermore, experimental tutoring allowed us to rigorously control the degree of acoustic modulations heard by the juvenile; for this experiment, we created song stimuli with no modulation to acoustic structure or timing (i.e. a single exemplar of each syllable was presented at a fixed intersyllable interval; electronic supplementary material).

We used a procedure identical to previous studies to assess context-dependent changes to song in adult zebra finches [17]. For these behavioural experiments, we housed males individually in a sound-attenuating chamber and collected FD and UD songs (see the electronic supplementary material) using a computerized, song-activated recording system (Sound Analysis Pro). Songs were digitally filtered (0.3–8 kHz) for offline analysis using custom-written scripts in matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). To collect FD song, we acutely exposed males to a conspecific female (for 30–60 s) and analysed the songs that they directed towards females. All songs that males produced when they were exposed to females were accompanied by a courtship dance and categorized as FD song (see the electronic supplementary material), and all UD songs were produced when males were in isolation. Isolation and acute exposure to conspecifics can affect hormone levels and, in turn, vocal performance [18]; consequently, it is possible that context-dependent variation in song performance is driven by rapid endocrine changes. However, because context-dependent changes to song are similarly observed in males that are continuously housed with females [9,19], we propose that endocrine changes are not the primary mechanism underlying context-dependent changes to song.

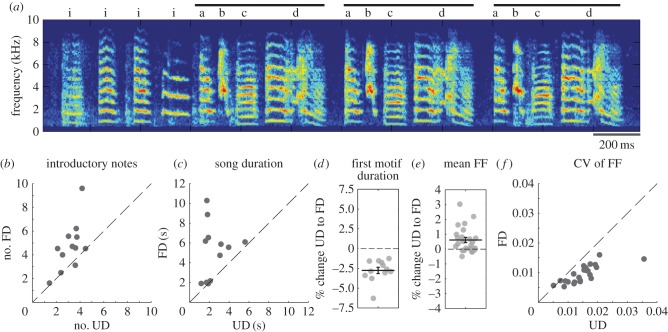

Zebra finch song consists of syllables arranged into a stereotyped sequence (motif) [20]. Each song contains one or more repetitions of the motif, preceded by a variable number of introductory notes (figure 1a). Following amplitude-based segmentation of song files, a single experimenter manually labelled songs for each individual bird and was blind to the social context of the songs. To assess context-dependent changes to song, we analysed song features that reliably change across social contexts: the number of introductory notes before song onset, song duration, the duration of the first motif in the song and the fundamental frequency (FF) of syllables with flat, harmonic structure (figure 1a; electronic supplementary material) [11].

Figure 1.

Singly reared birds demonstrate context-dependent modulations to song. (a) An example spectrogram of adult zebra finch song (colour indicates intensity). Arbitrary labels are assigned to individual acoustic elements (‘syllables’; above the spectrogram) for offline song analysis. Introductory notes are labelled as ‘i’. Black lines above labels indicate the ‘motif’ in this bird's song (syllables ‘abcd’). (b) FD songs were preceded by more introductory notes than UD songs. (c) FD songs were longer in duration than UD songs. (d) The duration of the first motif was significantly shorter during FD songs than during UD songs. For the sake of visualization, we plot the per cent change in mean motif duration for each bird. (e) The mean FF of syllables with flat, harmonic structure was significantly higher during FD songs than during UD songs, represented as the per cent change from UD to FD. (f) The CV of the FF was lower for FD song than for UD song, indicating that FD songs were more stereotyped. (b–d) Each point represents average values for both UD and FD songs from individuals. (e,f) Each point represents one syllable across UD and FD songs within a bird. The horizontal and vertical lines in d and e depict mean ± s.e. (Online version in colour.)

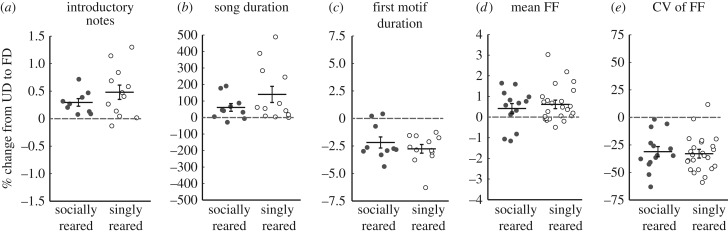

To supplement this primary analysis, we also compared the magnitude of context-dependent song modulations (% change) of singly reared males with that of males that were raised by their father and mother in a mixed-sex breeding colony (‘socially reared males'; electronic supplementary material).

All birds in this study were four-month-old birds that produced stereotyped, species-typical songs and that reliably produced courtship song to females (n = 12 singly reared; n = 10 socially reared).

3. Results and discussion

Singly reared males (i.e. operantly tutored and raised without exposure to the social modulation of song) demonstrated the full range of context-dependent changes to temporal and spectral features of song. Singly reared males produced significantly more introductory notes before FD song than before UD song (mixed-effects model for all analyses: F1,11 = 10.9, p = 0.0071; figure 1b) and produced significantly longer songs when singing to females than when singing alone (F1,11 = 10.6, p = 0.0077; figure 1c). Additionally, the FD songs of singly reared males were faster than their UD songs, as manifested by shorter motif durations during FD song (F1,11 = 20.6, p = 0.0009; figure 1d).

We analysed context-dependent changes to the FF of syllables with flat, harmonic structure [11]. Singly reared males significantly increased the FF of such syllables when producing FD song relative to when producing UD song (F1,23 = 9.7, p = 0.0049; figure 1e). Additionally, singly reared birds produced the FF of such syllables with less variability when singing to females than when singing alone, as manifested by the lower coefficient of variation (CV) during FD song (F1,23 = 43.1, p < 0.0001; figure 1f).

These results demonstrate that zebra finches raised without exposure to the social modulation of song during song tutoring significantly modulated the structure of their song in ways consistent with normally raised birds [11]. However, it remained unclear if the magnitude of this modulation was affected by exposure to such modulations during development. To this end, we compared the magnitudes of context-dependent changes between singly reared and socially reared birds. Across all five song features analysed above, there was no significant difference in the magnitude of modulation from UD song to FD song (% change) between singly reared and socially reared birds (t-tests or mixed-effects models: p > 0.15 for all comparisons; figure 2; electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Figure 2.

Singly and socially reared birds do not differ in the magnitude of song modulations. For (a–e), the per cent change from UD to FD song is plotted for each feature for singly reared birds (open circles) and socially reared birds (filled circles). Data for each syllable are plotted in (d) and (e). Horizontal and vertical lines depict mean ± s.e.

These results demonstrate that zebra finches socially modulate the structure of their song without witnessing an adult perform such social modulations during song learning. However, it remains possible that experiences with tutors outside the sensitive period for song learning or other social experiences during development (e.g. interactions with mothers or siblings) could shape this modulation. For example, it is possible that sensory and social experiences before or within the first 5 days after hatching could influence the ability to modulate song. However, breeding males do not extensively produce song around hatching [20], and, therefore, singly reared juveniles have limited opportunities to learn about these modulations during this period. As such, our data suggest that this type of vocal flexibility and the neural circuits that regulate this flexibility generally develop without imitative social learning in zebra finches [11,12].

Our results contrast sharply with the importance of developmental social learning for the ability to produce complex, species-typical vocalizations in many songbirds and for the social modulation of vocalizations in mice [3,9,16,21]. This also contrasts with other behaviours such as group integration and social preferences that have been found to be affected by social experiences during development in zebra finches [4,22,23]. Of particular interest is the fact that singly reared female zebra finches fail to demonstrate species-typical preferences for directed song [14], which suggests that the production and processing of socially modulated signals are differentially sensitive to developmental experiences.

The modulation of behaviour across social contexts can serve to ‘optimize’ the efficacy of behaviours [7]. Across species, various aspects of communication and social behaviour are impacted by social interactions or the social environment (e.g. [4,6,24]), and it will be important to assess the contributions of developmental social learning to such modulations of behaviour. In addition, it will also be important to assess the degree to which other, non-social forms of vocal flexibility (e.g. responses to urban noise) are influenced by developmental social interactions [25].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Y.W. Chou for help with data collection and T. Moulton for comments on the manuscript.

Ethics

All procedures were approved by the McGill University Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care: AUP #5977 and #7149.

Data accessibility

Data are uploaded to Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.r5d54 [26].

Authors' contributions

L.S.J. and J.B.D. collected and analysed songs. L.S.J. and J.T.S. analysed the data. L.S.J., J.B.D. and J.T.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors agree to be held accountable for the content of the manuscript and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

Research was supported by a NSERC Discovery Grant (J.T.S.; 2016-05016), a FQRNT Projet de Recherche en équipe (J.T.S.; PR-189949), a Heller Award (L.S.J.; Biology, McGill University) and a NSERC USRA (J.B.D.).

References

- 1.Reader SM. 2016. Animal social learning: associations and adaptations. F1000Research 5, 2120 ( 10.12688/f1000research.7922.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janik VM, Slater PB. 2000. The different roles of social learning in vocal communication. Anim. Behav. 60, 1–11. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galef BG, Laland KN. 2005. Social learning in animals: empirical studies and theoretical models. Bioscience 55, 489 ( 10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0489:SLIAES]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riebel K. 2009. Song and female mate choice in zebra finches: a review. Adv. Study Behav. 40, 197–238. ( 10.1016/S0065-3454(09)40006-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brainard MS, Doupe AJ. 2002. What songbirds teach us about learning. Nature 417, 351–358. ( 10.1038/417351a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljubičić I, Hyland Bruno J, Tchernichovski O. 2016. Social influences on song learning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 7, 101–107. ( 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.12.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taborsky B, Oliveira RF. 2012. Social competence: an evolutionary approach. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 679–688. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2012.09.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podos J, Lahti DC, Moseley DL. 2009. Vocal performance and sensorimotor learning in songbirds. Adv. Study Behav. 40, 159–195. ( 10.1016/S0065-3454(09)40005-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Matheson LE, Sakata JT. 2016. Mechanisms underlying the social enhancement of vocal learning in songbirds. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6641–6646. ( 10.1073/pnas.1522306113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolley SC, Doupe AJ. 2008. Social context-induced song variation affects female behavior and gene expression. PLoS Biol. 6, 0525–0537. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao MH, Brainard MS. 2006. Lesions of an avian basal ganglia circuit prevent context-dependent changes to song variability. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 1441–1455. ( 10.1152/jn.01138.2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolley SC, Kao MH. 2015. Variability in action: contributions of a songbird cortical–basal ganglia circuit to vocal motor learning and control. Neuroscience 296, 39–47. ( 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.10.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams H, Kilander K, Sotanski ML. 1993. Untutored song, reproductive success and song learning. Anim. Behav. 45, 695–705. ( 10.1006/anbe.1993.1084) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Clark O, Woolley SC. 2017. Courtship song preferences in female zebra finches are shaped by developmental auditory experience. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170054 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0054) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James LS, Sakata JT. 2017. Learning biases underlie ‘universals’ in avian vocal sequencing. Curr. Biol. 27, 3676–3682.e4. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehér O, Wang H, Saar S, Mitra PP, Tchernichovski O. 2009. De novo establishment of wild-type song culture in the zebra finch. Nature 459, 564–568. ( 10.1038/nature07994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toccalino DC, Sun H, Sakata JT. 2016. Social memory formation rapidly and differentially affects the motivation and performance of vocal communication signals in the bengalese finch (Lonchura striata var. domestica). Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 113 ( 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez EC, Elie JE, Soulage CO, Soula HA, Mathevon N, Vignal C. 2012. The acoustic expression of stress in a songbird: does corticosterone drive isolation-induced modifications of zebra finch calls? Horm. Behav. 61, 573–581. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.02.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinig A, Pant S, Dunning JL, Bass A, Coburn Z, Prather JF. 2014. Male mate preferences in mutual mate choice: finches modulate their songs across and within male–female interactions. Anim. Behav. 97, 1–12. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.08.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zann RA. 1996. The zebra finch: a synthesis of field and laboratory studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keesom SM, Finton CJ, Sell GL, Hurley LM. 2017. Early-life social isolation influences mouse ultrasonic vocalizations during male–male social encounters. PLoS ONE 12, e0169705 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0169705) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruploh T, Bischof HJ, von Engelhardt N. 2014. Social experience during adolescence influences how male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) group with conspecifics. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 68, 537–549. ( 10.1007/s00265-013-1668-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adkins-Regan E, Krakauer A. 2000. Removal of adult males from the rearing environment increases preference for same-sex partners in the zebra finch. Anim. Behav. 60, 47–53. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1448) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beecher MD, Brenowitz EA. 2005. Functional aspects of song learning in songbirds. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 143–149. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patricelli G, Blickley JJL. 2006. Avian communication in urban noise: causes and consequences of vocal adjustment. Auk 123, 639–649. ( 10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[639:ACIUNC]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James LS, Dai JB, Sakata JT.2018. Data from: Ability to modulate birdsong across social contexts develops without imitative social learning. Dryad Digit. Repos. ( ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- James LS, Dai JB, Sakata JT.2018. Data from: Ability to modulate birdsong across social contexts develops without imitative social learning. Dryad Digit. Repos. ( ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are uploaded to Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.r5d54 [26].