Abstract

In this work, we present a novel approach for performing 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) of co-culture systems. We demonstrate for the first time that it is possible to determine metabolic flux distributions in multiple species simultaneously without the need for physical separation of cells or proteins, or overexpression of species-specific products. Instead, metabolic fluxes for each species in a co-culture are estimated directly from isotopic labeling of total biomass obtained using conventional mass spectrometry approaches such as GC-MS. In addition to determining metabolic fluxes, this approach estimates the relative population size of each species in a mixed culture and inter-species metabolite exchange. As such, it enables detailed studies of microbial communities including species dynamics and interactions between community members. The methodology is experimentally validated here using a co-culture of two E. coli knockout strains. Taken together, this work greatly extends the scope of 13C-MFA to a large number of multi-cellular systems that are of significant importance in biotechnology and medicine.

Keywords: Metabolic flux analysis, isotopic tracers, microbial consortia, multi-organism systems, microbial communities

1. INTRODUCTION

Microbial communities are ubiquitous in nature and have a wide range of industrial applications including in biodegradation of organic compounds (Gilbert et al., 2003), conversion of toxic by-products (Sabra et al., 2010), production of biofuels (Bagi et al., 2007), and production of mixed products from single or multiple substrates (Bizukojc et al., 2010). Microbial communities carry out efficient bio-transformations that are the result of multiple complementary metabolic systems working together (Bader et al., 2010; Shong et al., 2012). It is now well appreciated that the capabilities of multi-microorganism systems cannot be predicted by the sum of their parts (Wintermute and Silver, 2010). Rather, synergistic interactions at different levels often result in better overall performance of these systems (Sabra et al., 2010). Co-culture metabolic engineering promises the assembly of complementary metabolic capabilities into functional systems (Gilbert et al., 2003), where the diversity of metabolic pathways and the ability of microorganisms to exchange metabolites dramatically increases the space of possible metabolic conversions (Kato et al., 2005). This flexibility could alleviate limitations encountered in single-species systems. Importantly, integration of diverse metabolic systems may result in more efficient substrate utilization (Sabra et al., 2010), make co-culture systems robust to environmental fluctuation (Brenner et al., 2008), and establish synergistic systems with other advantageous characteristics (Brenner et al., 2008; Keller and Surette, 2006; Kleerebezem and van Loosdrecht, 2007).

Current methods to gain insight into multi-species cultures include genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches (Lee, 2001; Tringe and Rubin, 2005; Wang et al., 2009). These ‘omics tools provide useful information about various aspects of a mixed culture. However, they do not provide information about the in vivo metabolic state of the cells, i.e. intracellular metabolic fluxes. 13C Metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) is the preferred experimental approach to elucidate detailed metabolic fluxes in biological systems (Antoniewicz, 2015). Over the past two decades 13C-MFA has been applied extensively to mono-culture systems (Crown and Antoniewicz, 2013). In 13C-MFA, a labeling experiment is performed by introducing a 13C-labeled substrate, known as the tracer, to the culture and allowing the tracer to be metabolized by the cells. The resulting labeling patterns in metabolites are then measured, e.g. by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Antoniewicz et al., 2011, 2007a), and flux distributions are estimated by iteratively fitting the measured data to a comprehensive model that reflects the known metabolic pathways of the organism (He et al., 2014; Young et al., 2008).

Until now, 13C-MFA has been applied almost exclusively to mono-culture systems. In a few examples where 13C-MFA was applied to co-cultures, it required physical separation of either proteins or cells to resolve species-specific labeling data, from which species-specific fluxes were calculated. This was accomplished either by direct separation of cells via centrifugation or fluorescence-assisted sorting, or indirect separation through purification of an over-expressed reporter protein (Rühl et al., 2011; Shaikh et al., 2008), where the labeling of the over-expressed protein was used as a proxy for whole-cell protein labeling. However, these approaches have significant disadvantages and limitations. Importantly, incomplete separation of cells or proteins produces inaccurate flux results (Ruhl et al., 2011). Additionally, fluorescence-assisted cell sorting is a rather slow separation technique, which makes it impractical for routine use in 13C-MFA, while methods based on an over-expressed reporter protein are limited to organisms with well-developed genetic tools. In addition, these approaches require a large sample size and estimate fluxes that do not reflect native metabolism of cells, but instead an altered metabolic state reflective of high protein overexpression. It is therefore desirable to develop a new methodology for 13C-MFA of co-cultures that overcomes these limitations.

In this work, we have developed a novel framework for co-culture 13C-MFA that accomplishes these objectives. Our approach does not require any physical separation of cells or proteins. Instead, we show that isotopic labeling of total biomass in a co-culture contains enough information to resolve not only species-specific fluxes with high precision, but also determine inter-species metabolite exchange and population dynamics. An important insight gained from this work is that judicious selection of isotopic tracers is extremely important for flux estimation in co-culture systems. We show that several commonly used tracers for 13C-MFA are not suited for flux elucidation in co-cultures; instead, other more appropriate isotopic tracers are proposed.

2. METHODS

2.1. Materials

Media and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). [1,2-13C]glucose (99.5 atom% 13C) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Isotec (St. Louis, MO). All solutions were sterilized by filtration.

2.2. Strain and growth conditions

Two E. coli knockout strains from the Keio Knockout Collection were used in this study, Δpgi and Δzwf. The strains were purchased from GE Life Sciences/Dharmacon (Pittsburgh, PA). The co-culture experiment was performed under aerobic growth conditions at 37°C in a mini-bioreactor with a working volume of 10 mL, as described previously (Crown et al., 2015). The two E. coli knockout strains were first pre-cultured individually until mid-exponential growth phase in M9 minimal medium with unlabeled glucose (OD600 = 0.47 for Δpgi, and OD600 = 1.24 for Δzwf). Next, 10 mL of M9 minimal medium containing 1.6 g/L of [1,2-13C]glucose was inoculated with 0.7 mL of the Δpgi pre-culture and 15 μL of the Δzwf pre-culture. The ratio of Δpgi biomass to Δzwf biomass was about 18:1. After 8.5 hrs of co-culture, cells were harvested by centrifugation for subsequent GC-MS analysis.

2.3. Analytical methods

Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600nm (OD600) using a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf BioPhotometer). The OD600 values were converted to cell dry weight concentrations using a pre-determined OD600-dry cell weight relationship for E. coli (1.0 OD600 = 0.32 gDW/L). Glucose concentration was measured with a YSI 2700 biochemistry analyzer (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH).

2.4. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry

GC-MS analysis was performed on an Agilent 7890B GC system equipped with a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm-phase thickness; Agilent J&W Scientific), connected to an Agilent 5977A Mass Spectrometer operating under ionization by electron impact (EI) at 70 eV. GC-MS analysis of tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) derivatized proteinogenic amino acids was performed as described previously (Antoniewicz et al., 2007a). Labeling of glucose in the medium was confirmed by GC-MS analysis of the aldonitrile pentapropionate derivative of glucose (Antoniewicz et al., 2011). Mass isotopomer distributions were obtained by integration and corrected for natural isotope abundances (Fernandez et al., 1996).

2.5. Nomenclature

The theoretical aspects of 13C-MFA are presented here using elementary metabolite unit basis vectors (EMU-BV), see Crown and Antoniewicz for details about EMU-BV framework (Crown and Antoniewicz, 2012). In short, an EMU is defined as a specific subset of a given compound’s atoms (Antoniewicz et al., 2007b), and an EMU-BV is a unique way of assembling substrate EMUs to form the measured metabolite (Crown et al., 2012). We use a subscript notation to denote atoms present in an EMU. For example, A234 indicates that the EMU is comprised of atoms 2, 3, and 4 of metabolite A. The subscript notation is also used to refer to metabolites from a specific population of a co-culture system. For example, for a co-culture composed of species #1 and species #2, Aspecies#1 refers to metabolite A in species #1. The MID is a vector that contains fractional abundances of the mass isotopomers of a given metabolite. A convolution (or Cauchy product) describes the condensation of two EMU’s and is denoted by “×” (Antoniewicz et al., 2007b).

2.6. EMU decomposition of networks

EMU decomposition of metabolic network models was conducted using the Metran software, which is based on the EMU framework (Yoo et al., 2008). The resulting EMU networks were decoupled into separate and smaller sub-networks using the technique described by Young et al., (2008), and further simplified using the technique described by Antoniewicz et al., (2007b).

2.7. Simulation of isotopic labeling data

Isotopic labeling data in the example models were simulated using Metran’s built-in feature for tracer experiment simulations. All simulated data are given in Supplemental Materials.

2.8. Metabolic flux analysis

13C-MFA was performed using the Metran software (Yoo et al., 2008), which is based on the elementary metabolite units (EMU) framework (Antoniewicz et al., 2007; Young et al., 2008). The E. coli network model used for flux calculations was described previously by Leighty and Antoniewicz (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2013), and is given in Supplementary Materials. The model includes all major metabolic pathways of central carbon metabolism, lumped amino acid biosynthesis pathways, and a lumped reaction for cell growth. In addition, the model accounts for the exchange of intracellular and atmospheric CO2 (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012), and G-value parameters to describe fractional labeling of amino acids. As described previously (Antoniewicz et al., 2007c), the G-value represents the fraction of a metabolite produced from labeled glucose, while 1−G represents the fraction that is naturally labeled from the inoculum. By default, one G-value parameter was included for each measured amino acid. Reversible reactions were modeled as separate forward and backward fluxes. Net and exchange fluxes were calculated as follows: vnet = vf−vb; vexch = min(vf, vb). Exchange fluxes were then scaled to 0–100% as follows: vexch [0–100%] = vexch / (|vnet| + vexch) × 100%.

For 13C-MFA of co-cultures, the model consisted of two compartments, each representing a separate species, and an f1-parameter that describes the fraction of species #1 in the co-culture (see text for further details). Flux estimation was repeated at least ten times starting with random initial values for all fluxes to find a global solution. In general, we required that the same solution was found at least three times starting with random initial values before the solution was declared a global solution. At convergence, 68% and 95% confidence intervals for all fluxes were computed for all estimated fluxes by evaluating the sensitivity of the minimized SSR to flux variations (Antoniewicz et al., 2006).

2.9. Goodness-of-fit analysis

To determine the goodness-of-fit, 13C-MFA fitting results were subjected to a χ2-statistical test. In short, assuming the network model is correct and data are without gross measurement errors, the minimized SSR is a stochastic variable with a χ2-distribution. The number of degrees of freedom is equal to the number of fitted measurements n minus the number of estimated independent parameters p. The acceptable range of SSR values is between χ2α/2(n−p) and χ21−α/2(n−p), where α is a certain chosen threshold value, for example 0.05 for 95% confidence interval. Models that produced SSR values above the threshold were considered statistically not acceptable.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. 13C-Metabolic flux analysis in a simple co-culture system

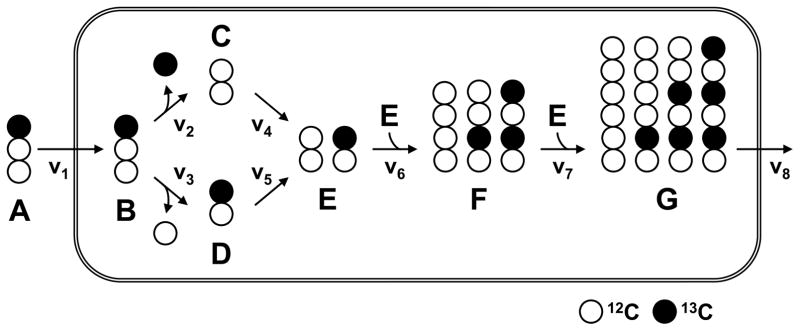

To illustrate the approach for 13C-flux analysis of co-cultures, we will first use a simple example model to highlight the general concepts. Consider the example network shown in Figure 1. In this system, metabolite A is the substrate and metabolites G and CO2 are the products. The system is assumed to be at metabolic and isotopic steady state. For a given value of the substrate uptake rate (v1), this network has one remaining free flux, namely the split between the two alternative pathways at metabolite B branch point. The two pathways have different carbon rearrangements: in the reaction from B to C (v2) the first carbon atom of B is lost as CO2, whereas in the reaction from B to D (v3) the third carbon atom of B is lost as CO2. Flux analysis is easily accomplished for this system using traditional 13C-MFA, for example, when metabolite A is 13C-labeled at the first carbon atom and the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolite E, F or G is measured.

Figure 1.

Simple example metabolic network model. Open circles denote 12C-atoms and filled circles denote 13C-atoms.

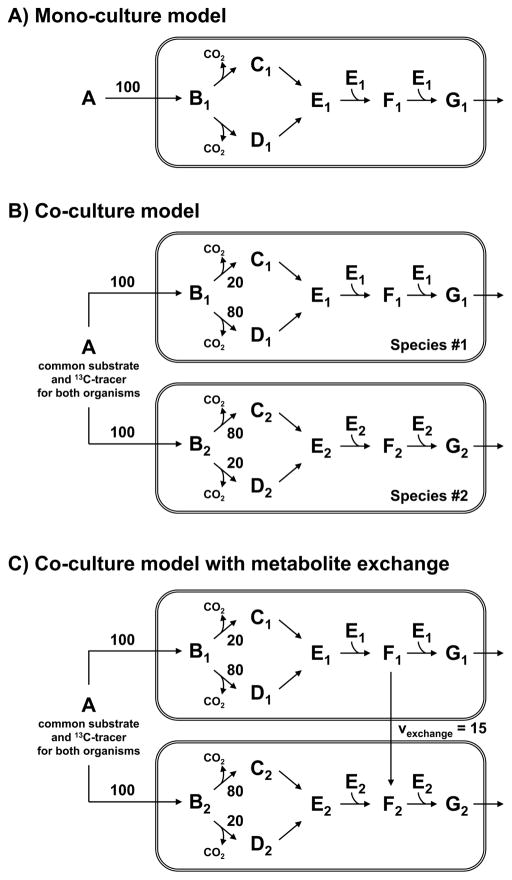

Next, consider the co-culture system composed of two species shown in Figure 2B. Here, both species consume the same substrate A and produce metabolites G and CO2. The two species also have the same underlying metabolic pathways and differ only in the split ratio at metabolite B branch point, where species #1 preferentially uses the pathway from B to D, whereas species #2 preferentially uses the pathway from B to C. The question that we would like to answer is whether it is possible to determine metabolic fluxes for the two species individually using only total biomass labeling, i.e. without physically separating the cells. The total biomass labeling is the result of the proportional contributions of each population’s internal labeling to the total labeling, i.e. assuming similar biomass composition for both species. For example, the total MID of metabolite G is the weighted sum of the MIDs of G from species #1 and species #2, after each is multiplied by the respective fraction of each species in the total cell population:

Figure 2.

Three metabolic network models with increasing level of complexity used to illustrate the general concepts of 13C-metabolic flux analysis of co-cultures.

In this equation, f1 represents the fraction of species #1 in the co-culture, and (1−f1) is the fraction of species #2. The co-culture system in Figure 2B has three unknown parameters that must be estimated in order to fully characterize it, namely the flux split at metabolite B branch point for species #1 (v2, species#1) and species #2 (v2, species#2), and the fraction of species #1 in the total cell population (f1). For simplicity, the substrate uptake rates for both species were normalized to 100. Therefore, to fully characterize this co-culture system at least three independent measurements are needed.

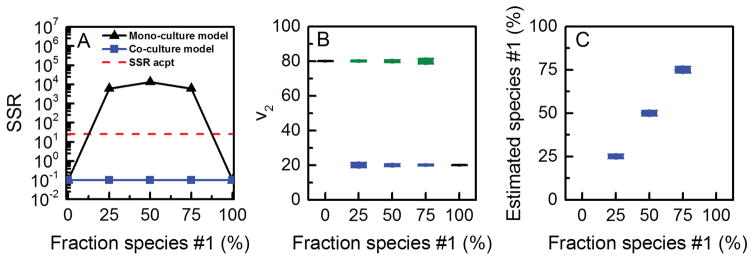

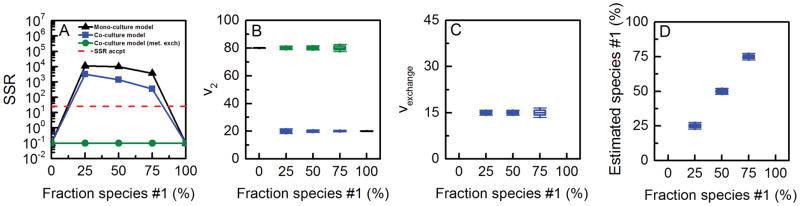

To evaluate the feasibility of estimating species-specific fluxes from total biomass labeling, we simulated MIDs of Etotal, Ftotal and Gtotal for different percentages of species #1 and species #2 in this co-culture, using f1 = 0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75 and 1. Note that the first and last data sets correspond to pure mono-cultures of species #2 and species #1, respectively. First, we attempted to fit the simulated MID data to a mono-culture model shown in Figure 2A. As expected, we obtained statistically acceptable fits only for MID data generated from mono-cultures (i.e. when f1 = 0 or 1) (Figure 3A); MIDs generated from co-cultures (i.e. when f1 = 0.25, 0.50 or 0.75) could not be fit to a mono-culture model. The SSR values were significantly higher than acceptable at 95% confidence level (Figure 3A). This result suggests that total labeling of metabolites E, F and G contain enough information to identify that the data is not derived from a simple mono-culture system. Next, we fit the data to a co-culture model (Figure 2B), which consisted of two compartments, each compartment representing a separate species and containing the complete set of reactions, and an f1-parameter. Using the co-culture model we obtained statistically acceptable fits for all data sets. As shown in Figure 3B, the true flux values of v2 in both species, i.e. v2, species#1 = 20 and v2, species#2 = 80, were estimated with narrow confidence 95% intervals. Furthermore, the fraction of species #1 in the co-culture was also accurately estimated with narrow confidence intervals (Figure 3C). This result confirms that it is possible to measure species-specific metabolic fluxes and relative population sizes of different species in a co-culture from total biomass labeling data without physically separating cells. To further evaluate if the results were sensitive to the relative population sizes of the two species, the analysis was repeated with smaller and larger fractions of species #1 (f1 = 0.1, …, 0.9). In all cases, accurate fluxes were estimated.

Figure 3.

Results of 13C-MFA obtained using a mono-culture model (results shown with black lines) and co-culture model (results shown with colored lines; blue = fluxes estimated for species #1; green = fluxes estimated for species #2). The input for 13C-MFA were simulated MIDs of Etotal, Ftotal, and Gtotal, assuming the fluxes shown in Figure 2B, and assuming metabolite A was labeled at the first carbon atom. The co-culture model produced statistically acceptable fits of all data sets. The estimated fluxes matched perfectly with the true flux values for both species.

3.2. Theoretical aspects of 13C-metabolic flux analysis of co-cultures

In the previous section, we demonstrated the feasibility of performing 13C-MFA in a co-culture system using total labeling data of metabolites E, F and G together. We also evaluated the feasibility of performing 13C-MFA in a co-culture system using total labeling data of metabolites E, F and G individually. When flux analysis was repeated using only MID of Etotal, we obtained statistically acceptable fits using both the mono-culture model and the co-culture model (Figure 4). This result suggests that metabolite E does not have enough isotopic information to resolve the fluxes in the two species. We also found that the estimated flux v2 in the mono-culture model corresponded to the population-average flux, i.e. the estimated flux v2 decreased with increasing fraction f1 (Figure 4). In contrast, when using MID of Ftotal, only the co-culture model produced a statistically acceptable fit of the data. However, when inspecting the 95% confidence intervals of the estimated fluxes we noted that fluxes v2,species#1, v2,species#2, and f1 could not be determined independently, resulting in very wide 95% confidence intervals (Figure 4). This result suggests that although metabolite F does contain enough information to detect that the MID data was not derived from a mono-culture system, it does not contain enough information to estimate the three unknown fluxes independently. Finally, we fit the MID of Gtotal. In this case, all three fluxes in the co-culture model could be determined accurately and precisely (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of 13C-MFA obtained using a mono-culture model (results shown with black lines) and co-culture model (results shown with colored lines; blue = fluxes estimated for species #1; green = fluxes estimated for species #2). The input for 13C-MFA was the simulated MID of Etotal (left column), Ftotal (middle column), or Gtotal (right column), assuming the fluxes shown in Figure 2B, and assuming metabolite A was labeled at the first carbon atom.

To explain these results, we expressed each measured metabolite in the network as a linear combination of EMU-BVs (Crown and Antoniewicz, 2012):

Where, α1 = (v2/v1)species#1, α2 = (v2/v1)species#2. The above equations indicate that in the co-culture model, metabolites E, F and G have 2, 3 and 4 EMU-BVs, respectively. As described previously in Crown and Antoniewicz (Crown and Antoniewicz, 2012), in order to estimate n independent unknown fluxes in a network model at least n+1 independent EMU-BVs are needed. Thus, in this system with three unknown fluxes at least four independent EMU-BVs are needed. Therefore, only metabolite G has enough EMU-BVs to make the model observable, assuming the EMU-BVs are independent for an appropriate choice of substrate labeling.

This example clearly illustrates the utility of analyzing the number of independent EMU-BVs in flux analysis studies, as it can inform how many independent fluxes can be estimated in theory. This is especially important when more fluxes are added to the model, for example, inter-species metabolite exchange fluxes as is described in the next section.

3.3. 13C-Metabolic flux analysis in a co-culture with inter-species metabolite exchange

A key characteristic of many microbial communities is inter-species metabolite exchange, where one species produces a product that is then taken up and metabolized by other species in the community. It would be highly desirable to have a method that can detect the presence of inter-species metabolite exchange and accurately and precisely determine these fluxes. To evaluate the feasibility of determining inter-species fluxes from total biomass labeling, we extended the co-culture model to include inter-species exchange of metabolite F (Figure 2C), where species #1 secretes metabolite F that is then taken up and further metabolized by species #2. We simulated total isotopic labeling of E, F and G for this extended model for different percentages of species #1 and species #2 in the co-culture and assuming an inter-species metabolite flux of 15. The MID data was then fit, first using a mono-culture model (Figure 2A), then using a co-culture model without metabolite exchange (Figure 2B), and finally using a co-culture model with metabolite exchange (Figure 2C). The first two models did not produce statistically acceptable fits. The SSR values were significantly higher than acceptable at 95% confidence level (Figure 5A). This suggests that the MID data in this system contains enough information to statistically detect inter-species metabolite exchange. Using the co-culture model shown in Figure 2C, we obtained statistically acceptable fits of all data. As shown in Figure 5, the true values of the four unknown fluxes, i.e. v2, species#1, v2, species#2, vexchange, and f1 were estimated with high precision. This result confirms that it is indeed possible to determine not only species-specific metabolic fluxes and relative population sizes in co-cultures, but also inter-species metabolite exchange without physically separating cells. It is also worth noting that estimation of inter-species exchange fluxes can be further improved by measuring the isotopic labeling of secreted metabolites directly.

Figure 5.

Results of 13C-MFA obtained using a mono-culture model (results shown with black lines), a co-culture model without metabolite exchange, and a co-culture model with metabolite exchange flux (results shown with colored lines; blue = fluxes estimated for species #1; green = fluxes estimated for species #2). The input for 13C-MFA were the simulated MIDs of Etotal, Ftotal, and Gtotal, assuming the fluxes shown in Figure 2C, and assuming metabolite A was labeled at the first carbon atom. Only the co-culture model with inter-species exchange of metabolite F produced statistically acceptable fits. The estimated metabolic fluxes matched perfectly with the true flux values.

3.4. 13C-Metabolic flux analysis in a simulated co-culture of two E. coli strains

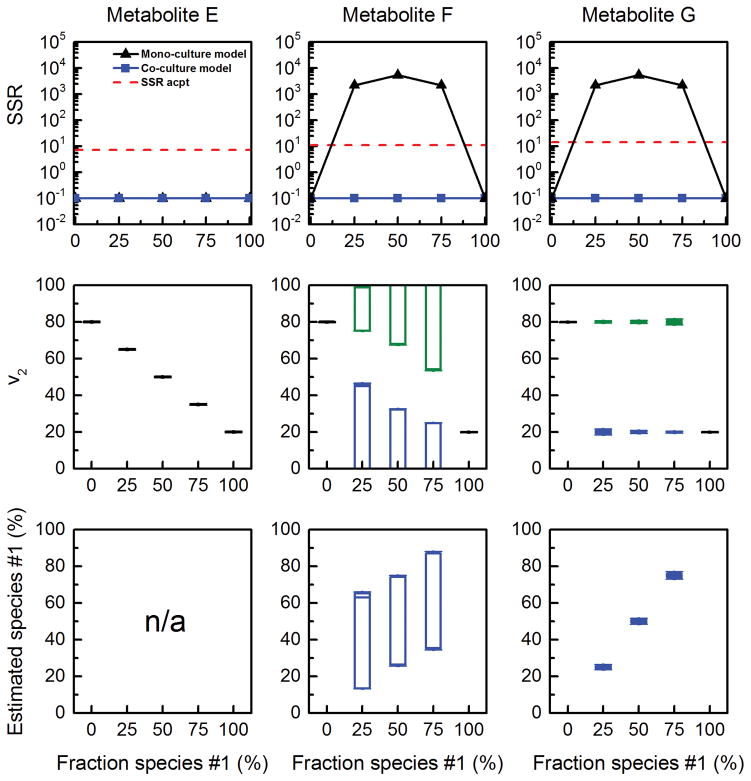

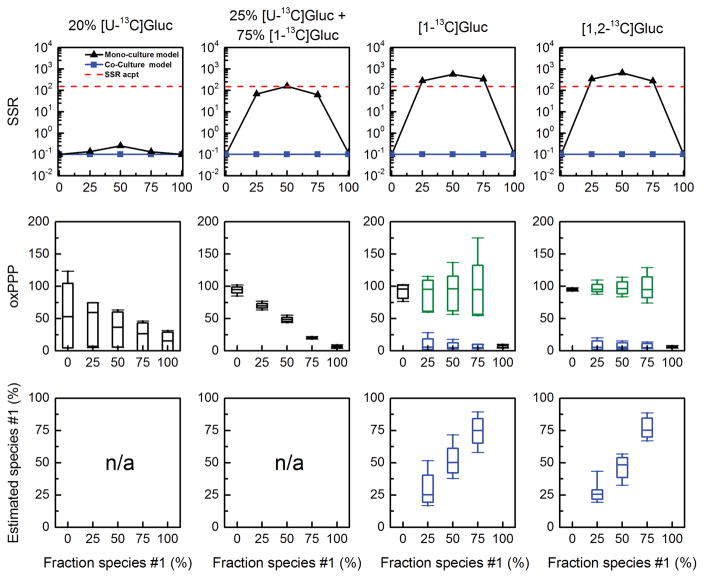

Thus far, we have demonstrated the feasibility of performing 13C-MFA in simple co-culture systems. Next, we extend our analysis to a realistically sized E. coli/E. coli co-culture system. Consider the co-culture of two E. coli species grown on glucose as the only carbon source, where each species has a distinct metabolic phenotype: E. coli species #1 predominantly uses glycolysis to metabolize glucose, whereas E. coli species #2 predominantly relies on the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP). The normalized oxPPP flux for species #1 is 5 (i.e. normalized to glucose uptake of 100), and the normalized oxPPP flux for species #2 is 95. We simulated total biomass amino acid labeling data typically measured by GC-MS for 13C-flux studies (Au et al., 2014) for this co-culture for different percentages of species #1 and species #2, and for four different isotopic tracers: [1-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, 20% [U-13C]glucose, and a mixture of 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose. For simplicity, we assumed identical biomass composition for the two E. coli species. In practice, this assumption can be easily validated using the methods described by Long and Antoniewicz (Long and Antoniewicz, 2014).

The simulated MID data was then analyzed, first using a mono-culture model and then a co-culture model. The results are summarized in Figure 6. For the tracers 20% [U-13C]glucose and 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose, the mono-culture model produced statistically acceptable fits of all simulated data, thus suggesting that these two tracers are not appropriate for flux studies of co-cultures. When inspecting the estimated fluxes, we observed that for 20% [U-13C]glucose only upper and lower bounds could be determined for the oxPPP flux, while for 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose the estimated oxPPP flux corresponded to the population-average oxPPP flux, i.e. the estimated oxPPP flux decreased with increasing fraction f1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Results of 13C-MFA for a simulated E. coli/E. coli co-culture, obtained using a mono-culture model (results shown with black lines) and a co-culture model (results shown with colored lines; blue = fluxes estimated for species #1; green = fluxes estimated for species #2). The input for 13C-MFA consisted of simulated MIDs of total biomass amino acids. Four different choices of glucose labeling were evaluated. Overall, [1,2-13C]glucose was the best tracer for 13C-flux analysis of the E. coli/E. coli co-culture.

In contrast, for the other two tracers, [1-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose, the mono-culture model did not produce statistically acceptable fits of the data. To obtain statistically acceptable fits it was necessary to use the co-culture model. For both tracers, the estimated species-specific oxPPP fluxes matched well with the true values, i.e. voxPPP,species#1 = 5 and voxPPP,species#2 = 95. In addition, the estimated fraction f1 matched well with the true fraction of E. coli species #1 in the co-culture. Overall, [1,2-13C]glucose produced more precise flux results than [1-13C]glucose; thus, we concluded that [1,2-13C]glucose is a better tracer choice for 13C-MFA studies of E. coli co-cultures.

3.5. 13C-Metabolic flux analysis in a co-culture of two E. coli knockout strains

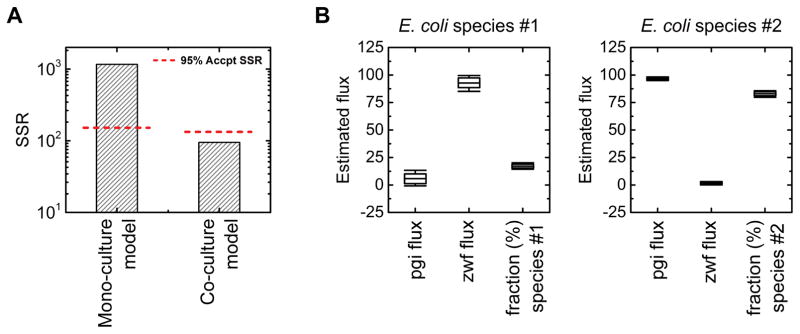

In this last section, we extend our analysis to a biological co-culture system of two E. coli knockout strains in order to demonstrate the accuracy and feasibility of our methodology using experimental data. Specifically, we investigated the co-culture of Δpgi (knockout of upper glycolysis) and Δzwf (knockout of oxidative pentose phosphate pathway). The two E. coli knockout strains were first pre-cultured individually on unlabeled glucose. Next, a co-culture was inoculated and cells were grown in the presence of [1,2-13C]glucose, the tracer that was found to be optimal in the previous section. During mid-exponential growth phase of the co-culture, a biomass sample was collected and labeling of total biomass amino acids was measured using GC-MS (Supplementary Materials). The labeling data was then analyzed, first using a mono-culture model and then a co-culture model. The co-culture model consisted of two identical compartmentalized E. coli models, each containing the complete set of reactions of the mono-culture model, and an f1 parameter that estimates the fraction of species #1 in the co-culture.

The flux analysis results are summarized in Figure 7. The mono-culture model did not produce a statistically acceptable fit of the data. The SSR value of 1161 was much higher than the maximum acceptable threshold value of 152 at 95% confidence level (Figure 7A). In contrast, the co-culture model produced an acceptable fit with an SSR value of 95, which was below the threshold value of 133 at 95% confidence level. The estimated pgi and zwf fluxes for the two strains matched well with the expected values (Figure 7B). The pgi flux of species #1, normalized to a glucose uptake flux of 100, was estimated to be 5 ± 4 (i.e. this is the Δpgi strain), while the zwf flux of species #2 was estimated to be 1 ± 1 (i.e. this is the Δzwf strain). The estimated fraction of species #1 (Δpgi) in the co-culture was 17% ± 2%. The small fraction of Δpgi biomass in the co-culture was expected, given that Δzwf has a significantly higher growth rate (0.59 h−1) than Δpgi (0.18 h−1) in mono-culture.

Figure 7.

Results of 13C-MFA for the co-culture system of two E. coli knockouts (Δpgi and Δzwf) cultured on [1,2-13C]glucose. (A) Minimized SSR values of best fits obtained using a mono-culture model and co-culture model, along with threshold SSR values at 95% confidence level. (B) Estimated species-specific metabolic fluxes for E. coli species #1 (Δpgi) and species #2 (Δzwf) obtained using the co-culture model.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that species-specific intracellular metabolic fluxes have been successfully estimated in a co-culture without separation of cells or proteins. These results demonstrate the utility of our methodology and pave the way for future studies of co-cultures with this approach.

4. CONCLUSIONS

13C-Metabolic flux analysis is an important tool in metabolic engineering. Although mono-culture 13C-MFA has been applied extensively over the past two decades, to our knowledge, there have been only a handful of studies attempting to conduct co-culture 13C-MFA. In this work, we present a novel framework for performing 13C-MFA of co-cultures that offers significant advantages over previous approaches. Unlike previous approaches, no physical separation of cells or additional genetic manipulations of cells is required to measure species-specific fluxes. In our approach total biomass labeling is used for flux elucidation. This not only simplifies experimental and analytical procedures for co-culture flux analysis, but also improves accuracy, and allows flux elucidation in systems where physical separation of cells or proteins is difficult, e.g. in co-cultures where cells have similar physical and/or proteome characteristics. In addition to quantifying species-specific metabolic fluxes, our approach estimates relative population sizes of the species in the co-culture and inter-species metabolite exchange. As such, it enables detailed studies of microbial communities including species dynamics and interactions between community members (Antoniewicz, 2013).

Recently, Ghosh et al. proposed an alternative, peptide-based methodology for co-culture 13C-MFA (Ghosh et al., 2014). Instead of relying on amino acid labeling, it was proposed that 13C-labeling data of species-specific peptides could be used to deconvolute fluxes of individual species in a co-culture. The advantage of this approach is that, in theory, it could be applied to complex co-cultures with a large number of species, i.e. assuming it is possible to identify and detect species-specific peptides. A notable disadvantage is, however, that because peptides contain inherently less flux information than amino acids, a large number of species-specific peptides is needed for this methodology, up to 30 peptides per microbial species (Ghosh et al., 2014). Another disadvantage is that the methodology cannot be applied to co-cultures with closely related species. For example, this methodology could not be applied to determine species-specific fluxes in the E. coli/E. coli co-culture described in this work, since both E. coli strains would have produced the same peptides.

Taken together, the new methodology for co-culture 13C-MFA developed here greatly extends the scope of 13C-MFA to include a large number of multi-cellular systems which are of significant importance in biotechnology, medicine, and other fields (Röling et al., 2010). As a proof-of-concept, we have analyzed a co-culture of two distinct E. coli species and, for the first time, successfully estimated accurate metabolic fluxes in multiple species. Analysis of other co-culture systems studied will be reported in separate publications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF-MCB-1120684 grant.

References

- Antoniewicz MR. Methods and advances in metabolic flux analysis: a mini-review. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:317–325. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR. Dynamic metabolic flux analysis--tools for probing transient states of metabolic networks. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:973–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Measuring deuterium enrichment of glucose hydrogen atoms by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2011;83:3211–6. doi: 10.1021/ac200012p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Accurate assessment of amino acid mass isotopomer distributions for metabolic flux analysis. Anal Chem. 2007a;79:7554–9. doi: 10.1021/ac0708893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Elementary metabolite units (EMU): A novel framework for modeling isotopic distributions. Metab Eng. 2007b;9:68–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Determination of confidence intervals of metabolic fluxes estimated from stable isotope measurements. Metab Eng. 2006;8:324–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kraynie DF, Laffend La, González-Lergier J, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic flux analysis in a nonstationary system: fed-batch fermentation of a high yielding strain of E. coli producing 1,3-propanediol. Metab Eng. 2007c;9:277–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au J, Choi J, Jones SW, Venkataramanan KP, Antoniewicz MR. Parallel labeling experiments validate clostridium acetobutylicum metabolic network model for 13C metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 2014;26:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader J, Mast-Gerlach E, Popović MK, Bajpai R, Stahl U. Relevance of microbial coculture fermentations in biotechnology. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:371–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagi Z, Acs N, Bálint B, Horváth L, Dobó K, Perei KR, Rákhely G, Kovács KL. Biotechnological intensification of biogas production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizukojc M, Dietz D, Sun J, Zeng AP. Metabolic modelling of syntrophic-like growth of a 1,3-propanediol producer, Clostridium butyricum, and a methanogenic archeon, Methanosarcina mazei, under anaerobic conditions. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2010;33:507–23. doi: 10.1007/s00449-009-0359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner K, You L, Arnold FH. Engineering microbial consortia: a new frontier in synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR. Rational design of 13C-labeling experiments for metabolic flux analysis in mammalian cells. BMC Syst Biol. 2012;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Antoniewicz MR. Parallel labeling experiments and metabolic flux analysis: Past, present and future methodologies. Metab Eng. 2013;16:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Antoniewicz MR. Selection of tracers for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis using Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) basis vector methodology. Metab Eng. 2012;14:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Long CP, Maciek R. Integrated 13C-metabolic flux analysis of 14 parallel labeling experiments in. Metab Eng. 2015;28:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Ca, Des Rosiers C, Previs SF, David F, Brunengraber H. Correction of 13C mass isotopomer distributions for natural stable isotope abundance. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:255–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199603)31:3<255::AID-JMS290>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Nilmeier J, Weaver D, Adams PD, Keasling JD, Mukhopadhyay A, Petzold CJ, Martín HG. A Peptide-Based Method for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis in Microbial Communities. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ES, Walker aW, Keasling JD. A constructed microbial consortium for biodegradation of the organophosphorus insecticide parathion. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;61:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Xiao Y, Gebreselassie N, Zhang F, Antoniewicz MR, Tang YJ, Peng L. Central metabolic responses to the overproduction of fatty acids in Escherichia coli based on 13C-metabolic flux analysis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:575–85. doi: 10.1002/bit.25124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Haruta S, Cui ZJ, Ishii M, Igarashi Y. Stable coexistence of five bacterial strains as a cellulose-degrading community stable coexistence of five bacterial strains as a cellulose-degrading community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7099–7106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7099-7106.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller L, Surette MG. Communication in bacteria: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:249–58. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem R, van Loosdrecht MCM. Mixed culture biotechnology for bioenergy production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH. Proteomics: a technology-driven and technology-limited discovery science. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:217–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR. COMPLETE-MFA: complementary parallel labeling experiments technique for metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 2013;20:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR. Parallel labeling experiments with [U-13C]glucose validate E. coli metabolic network model for 13C metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 2012;14:533–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long CP, Antoniewicz MR. Quantifying biomass composition by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2014;86:9423–7. doi: 10.1021/ac502734e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röling WFM, Ferrer M, Golyshin PN. Systems approaches to microbial communities and their functioning. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21:532–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rühl M, Hardt WD, Sauer U. Subpopulation-specific metabolic pathway usage in mixed cultures as revealed by reporter protein-based 13C analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1816–21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02696-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabra W, Dietz D, Tjahjasari D, Zeng AP. Biosystems analysis and engineering of microbial consortia for industrial biotechnology. Eng Life Sci. 2010;10:407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh AS, Tang YJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. Isotopomer distributions in amino acids from a highly expressed protein as a proxy for those from total protein. Anal Chem. 2008;80:886–90. doi: 10.1021/ac071445+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shong J, Jimenez Diaz MR, Collins CH. Towards synthetic microbial consortia for bioprocessing. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23:798–802. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe SG, Rubin EM. Metagenomics: DNA sequencing of environmental samples. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:805–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermute EH, Silver Pa. Emergent cooperation in microbial metabolism. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:407. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo H, Antoniewicz MR, Stephanopoulos G, Kelleher JK. Quantifying reductive carboxylation flux of glutamine to lipid in a brown adipocyte cell line. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20621–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706494200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JD, Walther JL, Antoniewicz MR, Yoo H. An Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) Based Method of Isotopically Nonstationary Flux Analysis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:686–699. doi: 10.1002/bit.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.