Abstract

Solar geoengineering refers to deliberately reducing net radiative forcing by reflecting some sunlight back to space, in order to reduce anthropogenic climate changes; a possible such approach would be adding aerosols to the stratosphere. If future mitigation proves insufficient to limit the rise in global mean temperature to less than 1.5°C above preindustrial, it is plausible that some additional and limited deployment of solar geoengineering could reduce climate damages. That is, these approaches could eventually be considered as part of an overall strategy to manage the risks of climate change, combining emissions reduction, net-negative emissions technologies and solar geoengineering to meet climate goals. We first provide a physical-science review of current research, research trends and some of the key gaps in knowledge that would need to be addressed to support informed decisions. Next, since few climate model simulations have considered these limited-deployment scenarios, we synthesize prior results to assess the projected response if solar geoengineering were used to limit global mean temperature to 1.5°C above preindustrial in an overshoot scenario that would otherwise peak near 3°C. While there are some important differences, the resulting climate is closer in many respects to a climate where the 1.5°C target is achieved through mitigation alone than either is to the 3°C climate with no geoengineering. This holds for both regional temperature and precipitation changes; indeed, there are no regions where a majority of models project that this moderate level of geoengineering would produce a statistically significant shift in precipitation further away from preindustrial levels.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘The Paris Agreement: understanding the physical and social challenges for a warming world of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’.

Keywords: geoengineering, 1.5, climate change

1. Introduction

The Paris agreement included the specific goal of ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C’ [1]. However, while there are emission scenario analyses that yield a 50% chance of meeting the 1.5°C goal [2,3], these pathways require near-immediate reduction to net-zero emissions. By contrast, current commitments to future mitigation of CO2 emissions are projected to result in warming closer to 3°C [4]. Approaches for ‘net-negative emissions’ carbon dioxide removal (CDR) [5] are already embedded in future emissions scenarios [6], although potentially at unrealistic scale [7,8]. Nonetheless, these technologies might eventually bring the temperature rise back below 1.5°C but only after a possibly lengthy period of overshoot [9].

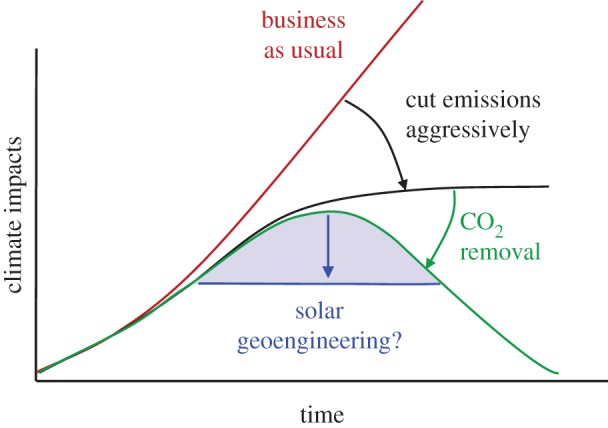

Given this context, solar geoengineering (or solar radiation management, SRM) could be considered as a possible supplement to other tools for managing long-term climate damages and risks [10–13] as illustrated qualitatively in figure 1. The purpose of solar geoengineering is to reduce climate changes by reflecting some sunlight back to space. The most frequently discussed approach is to inject aerosols or their precursors (e.g. SO2) into the stratosphere [14]; the same mechanism by which large volcanic eruptions cool the planet. Another approach is marine cloud brightening (MCB), which aims to increase cloud albedo through injection of sea-salt aerosols [15]; the effectiveness of this is less certain. Other techniques have also been proposed, from space-based [16], that are likely too expensive, to land- or ocean-albedo modification [17,18], that are either less scalable, have other environmental concerns (such as adding surfactants to the ocean), or are simply less well studied. An additional approach that shares some similar features is to deliberately thin cirrus clouds and hence increase outgoing long-wave radiation [19]; the effectiveness of this approach is even more uncertain [20]. For each of the key approaches, table 1 summarizes the confidence level in being able to achieve useful radiative forcing, and advantages and disadvantages.

Figure 1.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, combined with future large-scale atmospheric CO2 removal (CDR), may lead to long-term climate stabilization, but with some potentially significant overshoot of desired temperature targets. There is thus a possible role for limited and temporary solar geoengineering as part of an overall strategy to reduce climate impacts during the overshoot period. (Solar geoengineering as an alternative to mitigation would require extremely large forcing to be sustained for millennia, and is thus not necessarily realistic or advisable.) This graph, adapted from [10], represents climate impacts conceptually, not quantitatively; see figure 3 for a specific representative scenario. (Online version in colour.)

Table 1.

Summary of solar geoengineering options, confidence in ability to produce radiative forcing (RF), key advantages and disadvantages relative to stratospheric sulfate. Any solar geoengineering approach will introduce additional concerns, e.g. [21].

| method | confidence that substantial global ΔRF (e.g. >3 W m−2) is achievable | advantages | disadvantages relative to stratospheric sulfate |

|---|---|---|---|

| stratospheric sulfates | very high: current technologies can likely be adapted to loft materials and disperse SO2 at relevant scales | similarity to volcanic sulfate gives empirical basis for estimating efficacy and risks | |

| other stratospheric aerosols | moderate: depends on aerosol, lofting similar to sulfate but aerosol dispersal much more uncertain | some solid aerosols may have less strat. heating and minimal ozone loss | harder to bound uncertainty since not naturally occurring in stratosphere |

| marine cloud brightening | uncertain: observations support wide range of CCN impact on albedo; substantial process uncertainty | ability to make local alterations of albedo; and modulate on short timescales. | only applicable on marine stratus covering approximately 10% of the Earth means RF inherently patchy |

| cirrus thinning | uncertain: deep uncertainty about fraction of cirrus strongly dependent on homogeneous nucleation; no studies examining diffusion of CCN | works on longwave radiation so could provide better compensation | maximum potential cooling limited; zonal distribution of RF constrained by distribution of cirrus |

| space based | low physical uncertainty, but deep technological uncertainties | possibility of near ‘perfect’ alteration of solar constant | substantially more expensive |

While these approaches can reduce the global mean temperature, the resulting climate is not the same as one with the same global mean temperature but achieved through mitigation alone; some of these differences will be explored in §3. However, unlike mitigation, solar geoengineering would affect the climate quickly, and thus could provide a unique additional tool for managing climate change. The amount and duration of a solar geoengineering deployment required to maintain a specific target such as 1.5°C is directly related to the characteristics of temperature overshoot [9]. Reducing the cumulative anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions would reduce the peak amount of such a deployment, while long-term net-negative emissions would limit the duration of overshoot and hence deployment.

Mitigation remains essential. Solar geoengineering would not compensate all climate damages (e.g. ocean acidification), and the risks and side effects of geoengineering will increase with the amount used [22]. Further, while several degrees of cooling are almost certain to be achievable for some approaches (table 1), the maximum cooling potential is unclear. And finally, even moderate deployment imposes a constraint on future generations to either maintain the deployment or accept the consequences of phasing it out. In the absence of strong mitigation the duration of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations could be substantial.

The climate sensitivity to increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations is uncertain [23], so while the best estimate for the increase in global temperature rises in close proportion to cumulative emissions [24], there is substantial uncertainty for any particular emissions pathway. The 1.5°C target has been operationally interpreted as an emissions pathway that meets 1.5°C with some probability, often 50% or 66% [4] (although a probability is not specified in the Paris agreement). Thus, in addition to providing a possible option for supplementing mitigation trajectories that are insufficient to meet the 1.5°C goal, the ability to implement solar geoengineering if needed appears to be the only way to be certain of limiting global average temperature increases to 1.5°C even if emissions follow proposed 1.5°C-consistent pathways.

The prospect of using solar geoengineering to supplement more conventional climate risk mitigation in reaching a temperature target highlights the fact that global mean temperature is simply a proxy for a broad collection of climate impacts [25]. It is plausible that solar geoengineering could meet a temperature target while failing to reduce many of the specific climate risks that are the implicit goal of any such global temperature target.

Based on current knowledge it seems likely that solar geoengineering could reduce many climate risks for most people [26]. However, current knowledge about the climate response and impacts is insufficient to support an informed decision (e.g. [13,27–29]). Furthermore, even if analysis demonstrated a reduction in aggregate climate damages, there are additional ethical concerns such as distributional issues (e.g. [30,31]; these lead to arguments both for and against deployment) and socio-political risks that include the difficulties of governance [32–35], the potential for conflict and the potential for a geoengineering deployment to impact the commitment to mitigation [36]. There are additional societal concerns surrounding the research itself [37]. We briefly review what is known in the next section, with a particular focus on recent research results, trends and open questions. Additional details can be found in a number of recent reviews of solar geoengineering [30,38–41].

Section 3 then assesses the projected climate response of solar geoengineering in the context of a limited deployment aimed at avoiding an increase in global mean temperature above 1.5°C in the presence of mitigation that would otherwise result in a 2.5–3°C temperature rise, including both a representative quantification of figure 1 as well as projections of regional temperature and precipitation impacts. Many geoengineering simulations to date have been designed primarily to understand how models respond differently to different types of radiative forcing, rather than to simulate representative future deployment scenarios—which could lead to misinterpreting the results as being representative of any geoengineering deployment strategy; one exception that simulates geoengineering in an overshoot scenario is Tilmes et al. [42]. The projection in §3 relies on existing climate model simulations, using a dynamic climate emulator [43] to predict the climate response for different forcing trajectories.

2. The state of knowledge

Supporting an informed decision regarding responsible deployment of any form of solar geoengineering would presumably require at least (i) an assessment of the best estimate for the climate response and associated human and ecosystem impacts associated with different deployment choices, as well as (ii) an assessment of the confidence in those estimates. In addition to these physical-science inputs that we primarily focus on here, a responsible decision would also need to understand socio-political ramifications including expected governance.

Numerous climate model simulations of solar geoengineering have been conducted, either with an idealized reduction of the solar constant or using simulations of specific approaches. Some general characteristics of the expected response to any form of solar geoengineering can be assessed from the former; this case also allows for straightforward multi-model comparisons (as in the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project; GeoMIP [44,45]) since the identical simulation can be conducted in each model.

A reduction in sunlight would cool the planet everywhere, though not with the same spatial or seasonal pattern as the warming due to increased GHG, both due to the different mechanism of radiative forcing and the different spatial distribution of radiative forcing. For example, a robust result from climate model simulations of either insolation reduction [45,46] or tropical aerosol injection is an overcooling of the tropics and undercooling of the poles (i.e. less polar amplification than occurs for GHG-warming), due to the spatial pattern of insolation. This has consequences beyond simply spatial differences in the fraction of CO2-warming offset by a given level of solar reduction; for example, the change in equator-to-pole temperature gradients in these simulations yields a shift in the mid-latitude storm track [47].

A second broad conclusion regards precipitation changes. The warming due to increased greenhouse gases has two counteracting influences on precipitation. A warmer world holds more moisture, increasing the strength of the hydrological cycle. At the same time, increased atmospheric GHG concentrations warm the entire troposphere, increasing stability and reducing convection; this ‘fast’ response [48] is thus of opposite sign to the ‘slow’ response due to warming. Transpiration also decreases with increases in CO2, further reducing precipitation [49]. Cooling the planet through a solar reduction counteracts the expected increase in precipitation from the temperature-dependent ‘slow’ response, but because of the different mechanism of radiative forcing, does not compensate for the ‘fast’ responses. As a result, a robust expectation from any solar geoengineering approach is that it results in less global mean precipitation for a given global mean temperature than if the same temperature were achieved through mitigation alone [50,51]. One consequence of this is that using solar geoengineering to return temperatures back to preindustrial levels will overcompensate precipitation, and will almost certainly not represent an optimum balancing of risks [22,26].

Based on the above observations, care should be taken in interpreting projected climate responses from solar reduction simulations, for three reasons. First, any specific approach such as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) will impact the climate differently from a solar reduction. (Although comparisons [47,52–54] can be difficult to interpret due to uncertainty as to which differences result from the different mechanism of radiative forcing, and which are due to the different spatial distribution.) Second, many simulations have compensated all of the global mean temperature rise due to increased atmospheric CO2 (e.g. GeoMIP scenarios G1 and G2 [44]), resulting in overcooling in some regions and overcompensation of precipitation changes. These simulation results can still be useful provided they are scaled to more representative scenarios, as in §3.

The third and more subtle reason for care in evaluating current simulations is that the impacts will depend on design choices such as the latitude at which to inject aerosols into the stratosphere: simulations with a uniform solar reduction or with equatorial aerosol injection may result in climate outcomes that would be avoidable through different choices. The dominant residual temperature pattern of overcooling the tropics and undercooling the poles is due to the different zonal distribution of radiative forcing. However, since the stratospheric Brewer–Dobson circulation is broadly poleward, aerosol injection away from the tropics can be used to increase aerosol concentrations at higher latitudes [55,56], reducing or eliminating differences in the equator to pole temperature gradients [57]. Similarly, altering the injection amount separately in each hemisphere [57] can minimize shifts in the intertropical convergence zone and associated tropical precipitation impacts [58]. That is, a fundamental feature of solar geoengineering is that it is a design problem [59–62]. The extent to which it can be designed to better manage climate outcomes is as yet unknown, and thus how well solar geoengineering could compensate for tropospheric climate effects of increased atmospheric GHGs is still uncertain.

Specific technical approaches for solar geoengineering will have different impacts.

Stratospheric aerosols both scatter and absorb, heating the stratosphere and affecting stratospheric dynamics and water vapour concentrations [47,63–65], which in turn influence surface climate [47]. Aerosols also affect stratospheric ozone chemistry [66–69], though as stratospheric chlorine concentrations recover the aerosol impact on ozone concentrations will decrease [70]. These effects depend on the latitude, altitude and season where aerosols are injected [65]. While sulfate is often assumed, different aerosols could be chosen that have less stratospheric heating and associated impact on dynamics [47,71] or that might reverse the sign of the effect on ozone [72]. Furthermore, many of the earlier SAI simulations do not include some potentially relevant physical processes (e.g. table 2 in [67]). Climate models are now capable of simultaneously capturing aerosol microphysics, interactions with stratospheric chemistry, and coupling with stratospheric dynamics in a fully coupled model [73,74].

MCB [15] involves injecting sea-salt aerosols into marine boundary layer clouds in order to increase cloud albedo through the indirect aerosol effect. This would affect the climate differently from SAI [52]. Cloud–aerosol interactions, however, are one of the largest areas of uncertainty in climate change, and it is unclear over what fraction of the ocean MCB might be effective. While the radiative forcing from stratospheric aerosols is potentially relatively uniform in space and time, MCB would create spatially heterogeneous forcing and potentially more spatially heterogeneous climate effects. This could have both advantages and disadvantages in the ability to compensate for the regional pattern of climate changes from CO2; indeed a combination of SAI and MCB might lead to improved outcomes.

Uncertainty is clearly a significant concern. Conceptually this can be separated into uncertainty in the processes that result in a (negative) radiative forcing, and uncertainty in how the climate then responds to that forcing. While not strictly separable, this conceptualization is valuable for making judgements about the extent to which uncertainty might be resolvable.

Uncertainty in individual processes, such as aerosol microphysical growth assumptions or chemical reaction rates in the case of stratospheric aerosols, can in principle be reduced through small-scale process-level field experiments [75,76] and/or better observations after future large volcanic eruptions [77]; cloud–aerosol interactions underpinning MCB could also be tested at relatively small scale [78]. Indeed, conducting these process experiments would have co-benefits for climate science [79], complementing observations (e.g. [80]). Furthermore, if, for example, stratospheric aerosol geoengineering were deployed, the aerosol properties—their size and spatial distribution—could be measured, and the injection rate adjusted in response to any differences between predictions and observations; this might allow the desired radiative forcing to be produced despite some amount of process uncertainty.

However, an experiment to measure the regional climate response to geoengineering would require substantial forcing and/or considerable time [81]. As a result, there will always be some uncertainty in the regional climate projections prior to deployment, just as there remains uncertainty today in the response to increased GHG concentrations [23]. Indeed, the primary source of uncertainty is the same—uncertainty in the strength of regional feedbacks that largely determine the regional climate responses. At least for a solar reduction, the spread across model predictions is reduced with moderate geoengineering rather than increased [82]. Maintaining global mean temperature at 1.5°C using solar geoengineering could arguably reduce some uncertainties regarding future climate changes relative to the same emissions trajectory without solar geoengineering. A feedback process, similar to that described above for modifying the strategy in response to observed aerosol properties, might also be used to maintain global mean temperature [83] or several degrees of freedom of the spatial pattern of temperature [57,61].

Further research is required to address a number of issues raised above. This includes, for example, (i) taking a design perspective to ask what climate outcomes are or are not achievable through different choices, (ii) translating climate response into impacts assessment—how might geoengineering influence specific risks, and (iii) reducing uncertainties through observations and field experiments, and understanding how one might manage irreducible uncertainties.

There is also significant research in geoengineering beyond the physical climate science summarized above. This includes evaluations of the ethics of climate intervention, social science to better understand how different publics might respond to the idea [84], and research aimed at building necessary governance. Just as the climate science implications of geoengineering are at least somewhat contingent on assumptions about how geoengineering is used—whether it is a limited supplement to aggressive mitigation policy or portrayed as a substitute—the ethics, social science and governance conclusions will also depend on the framing. Substantially, more research will also be required in all of these areas over the coming decades.

3. Projected climate response for 1.5°C

(a). A portfolio of options

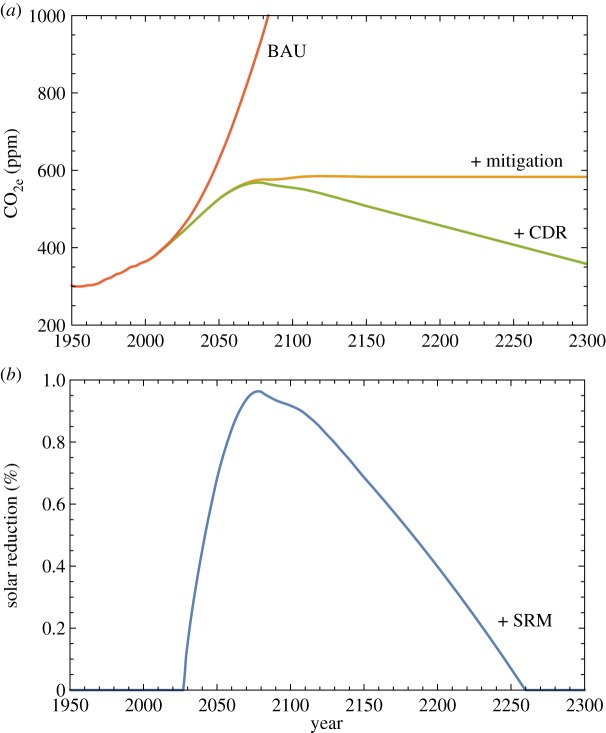

To illustrate how solar geoengineering could be used as part of an overall strategic approach to manage climate risk, we start by defining a set of hypothetical scenarios: (i) following the RCP8.5 representative concentration pathway [85] to illustrate the no-mitigation, business-as-usual, baseline, (ii) following the RCP4.5 pathway to illustrate responses to a robust mitigation effort, (iii) the RCP4.5 pathway augmented with sufficient CDR to reduce atmospheric concentrations at 1 ppm yr−1, leading to a peak warming of approximately 2.7°C in our projection (figure 3) and (iv) this augmented-RCP4.5 pathway, but with sufficient solar geoengineering to maintain global mean temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C; for simplicity, we ignore potentially non-negligible carbon-cycle feedbacks that would reduce the CO2 concentrations if temperatures were reduced through solar geoengineering [86]. The concentrations (expressed in CO2e) and required solar reduction are shown in figure 2.

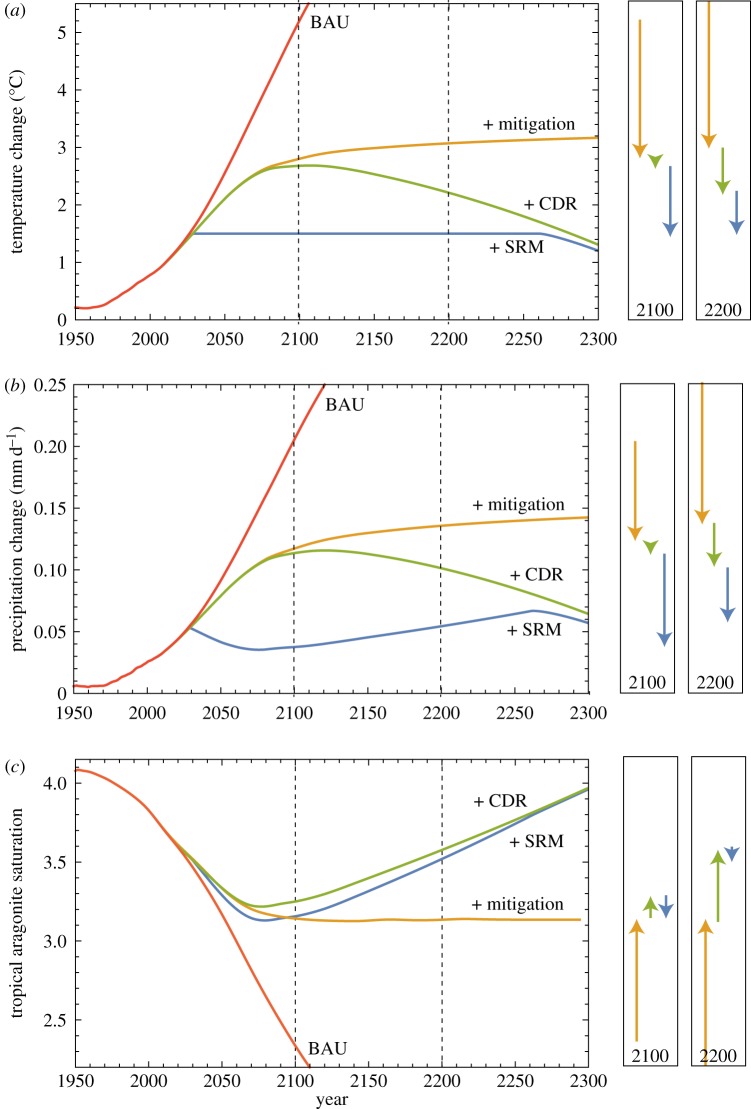

Figure 3.

Not all climate variables respond to solar geoengineering the same way. The global-mean temperature (a), global mean precipitation (b) and tropical aragonite saturation state (c) are shown for the cases in figure 2: RCP8.5 (BAU), RCP4.5 (+mitigation), RCP4.5 augmented with long-term CO2 removal (+CDR) and RCP4.5, CDR, and sufficient solar geoengineering to maintain temperature at 1.5°C (+SRM). SRM acts quickly while CDR acts slowly: in this scenario, the compensation of climate change due to CO2 emissions is primarily due to SRM in 2100; by 2200 both SRM and CDR contribute. Temperature and precipitation responses are estimated from median of 12 models participating in GeoMIP and aragonite saturation state responses are estimated from Kwiatkowski et al. [94] (see appendix A; the electronic supplementary material). (Online version in colour.)

Figure 2.

Representative scenarios used in figures 3–6. (a) CO2-equivalent (CO2e) for representative concentration pathway RCP8.5 (representing a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario), RCP4.5 (to represent mitigation) and RCP4.5 augmented with significant levels of long-term CO2 removal (+CDR) sufficient to reduce concentrations by 1 ppm yr−1. The solar reduction (+ SRM) used in figure 3 is shown in b. For simplicity, the carbon-cycle feedbacks between the reduced temperatures associated with using solar geoengineering and resulting CO2 concentrations is ignored. (Online version in colour.)

While the RCP4.5 pathway considered here already includes some CDR [87], its emissions fall well within the range of emissions in scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group 3 database [88] after negative emissions are excluded (electronic supplementary material, Figure S5). The augmented CDR pathway assumed here is deliberately arbitrary for illustration purposes only. We use a sigmoidal ramp-up (as in [9]) from 2050 to 2100 to a sustained rate defined through its impact on concentration (electronic supplementary material, Figure S4). A reduction of 1 ppm yr−1 would require reducing atmospheric CO2 by 7.8 Gt yr−1. Approximately, half of anthropogenic CO2 emissions are currently absorbed by the oceans and biosphere, and the same processes would operate in reverse [89], so that this level of reduction might require of order 15 Gt CDR and storage per year with more precise quantification dependent on uncertainties in the carbon cycle model. This rate is near the high end considered in the working group 3 database [9,90], and higher than some estimates that evaluate terrestrial biomass potential [91–93]. Higher or lower removal rates will result in shorter or longer overshoot of 1.5°C, respectively.

We estimate the global mean response to these scenarios first, and the regional response in §3b; these rely on climate emulators tuned to match the response of 12 climate models participating in GeoMIP, see appendix A and the electronic supplementary material.

While solar geoengineering could maintain temperature at 1.5°C, not all climate variables will respond the same way. Some variables will be more strongly affected (global mean precipitation will be restored even closer to preindustrial than global mean temperature), while others would be under-compensated or exacerbated (e.g. ocean acidity will not be strongly affected by geoengineering; stratospheric ozone loss would be made worse if stratospheric sulfate aerosols are used for cooling). This principle is illustrated in figure 3(a–c), which shows global mean temperature, global mean precipitation and tropical aragonite saturation state under our four pathways. With each additional climate risk mitigation tool, global temperatures are decreased and, finally, solar geoengineering is used to stabilize global temperature. Global precipitation is proportionally restored with mitigation and CDR, but the addition of solar geoengineering reduces precipitation faster than it cools. On the other hand, because surface ocean carbonate chemistry is more sensitive to atmospheric concentrations of CO2 than to changes in surface air temperature, solar geoengineering has little effect on ocean acidification. Tropical aragonite saturation state (ΩA), an important proxy for viability of calcifying organisms, is illustrated for the four pathways in figure 3(c). Solar geoengineering has a small exacerbating effect on ΩA here due to cooler temperatures and our assumed identical atmospheric CO2 concentrations; the sign of the effect might change with a carbon-cycle model that accounts for the impact of temperature on CO2. The way that temperature, precipitation and other effects interact to cause impacts is not necessarily obvious. In the case of coral bleaching, cooler sea surface temperatures have a much greater effect reducing bleaching than reduced ΩA increases it [94]; in the case of agricultural impacts, for example while solar geoengineering tends to decrease precipitation, in combination with cooler temperatures and high atmospheric CO2, simulations have shown a net positive effect on crop yields [95].

The climate changes induced by increased GHG concentrations are complex, but because the impacts typically increase with the global mean temperature, a single number such as 1.5°C or 2°C can be a proxy for a wide collection of climate impacts, with the climate impacts of 1.5 being less than those corresponding to 2°C (although there may be other trade-offs in choosing a target). Since geoengineering would not affect the climate the same way, a lower global mean temperature anomaly achieved using geoengineering does not necessarily lead to lower aggregate climate risks. Choosing an appropriate level that balances different risks to the climate system will not be straightforward.

The peak level of solar geoengineering in figure 2 is approximately 1.7 W m−2. For context, with SAI this would require of order 3 Tg S yr−1 if injected as H2SO4 [96] and 5 Tg S or more if SO2 were injected instead (the most commonly simulated approach); the latter is consistent for example with the 10 Tg yr−1 of SO2 found by Kravitz et al. [57] per degree of cooling. Efficacy uncertainty for MCB is currently too high to compute similar estimates.

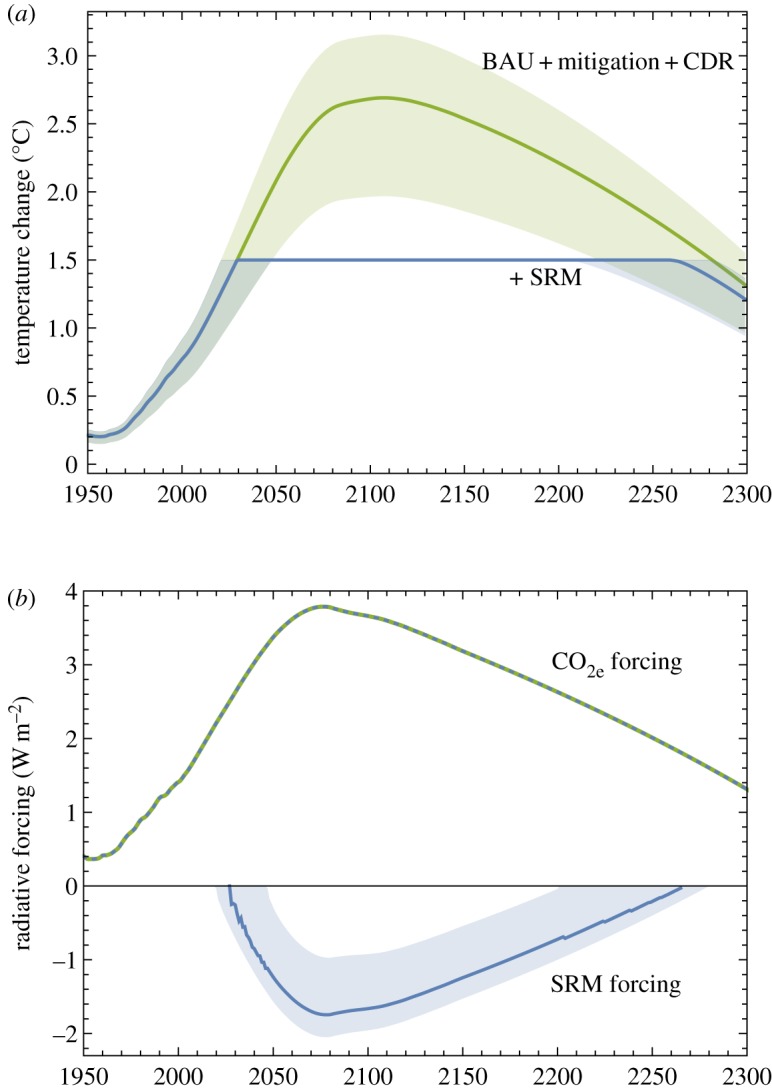

Figure 3 illustrates the median projected response across 12 models. However, an important feature of climate change projections is the uncertainty in climate sensitivity. Figure 4 shows the range of temperature response and forcings across the 12 models considered both with and without geoengineering, assuming that the amount of geoengineering is adjusted to maintain the 1.5°C target in each model. Because of the short timescales between implementation and effect, solar geoengineering would also increase the certainty of being able to achieve a target.

Figure 4.

Uncertainty in climate sensitivity results in a range of temperature outcomes for a given CO2-concentration pathway; the multi-model median response and range across the 12 models considered here is shown for the case with long-term CO2 removal both with and without solar geoengineering. (a) Solar geoengineering could be used to achievea 1.5°C target independent of climate sensitivity uncertainty. (b) The range of forcing from solar geoengineering across the 12 models and from CO2e; analysis uses % solar reduction and concentration, respectively, but these are plotted as approximate radiative forcing to enable comparison between them. CO2 forcing is estimated as 5.35 times the log of the concentration change. Because of the short timescales associated with solar geoengineering, uncertainty in climate response can be compensated for with control over solar geoengineering forcing. (Online version in colour.)

We next turn to an assessment of the regional response to geoengineering used to maintain a 1.5°C target, using the same hypothetical mitigation, CDR and solar geoengineering scenarios.

(b). Regional climate response

As in §3a, rather than conducting new simulations of geoengineering specific to a 1.5°C global mean temperature target, we rely on a climate emulator to project the response based on existing climate simulations, using the same 12 GeoMIP climate models’ response to a solar reduction. The regional projection is based on the emulator developed and verified in [43] (see appendix A); this relies on an assumption of linearity, which has been validated to be a good approximation for many, but not all variables. Because of the observation made earlier regarding both the mechanism and spatial pattern of radiative forcing, the regional response predictions should be interpreted cautiously; we chose this set of models because it provides an opportunity to assess inter-model robustness. The only geoengineering simulation we are aware of that uses a similar scenario is [42] in which stratospheric sulfur injections are used to maintain global mean temperature near 2°C in an overshoot scenario that would otherwise peak near 3°C; their results are broadly consistent with results here in that their geoengineered climate is more similar to a 2°C climate achieved through mitigation alone than either are to the 3°C climate.

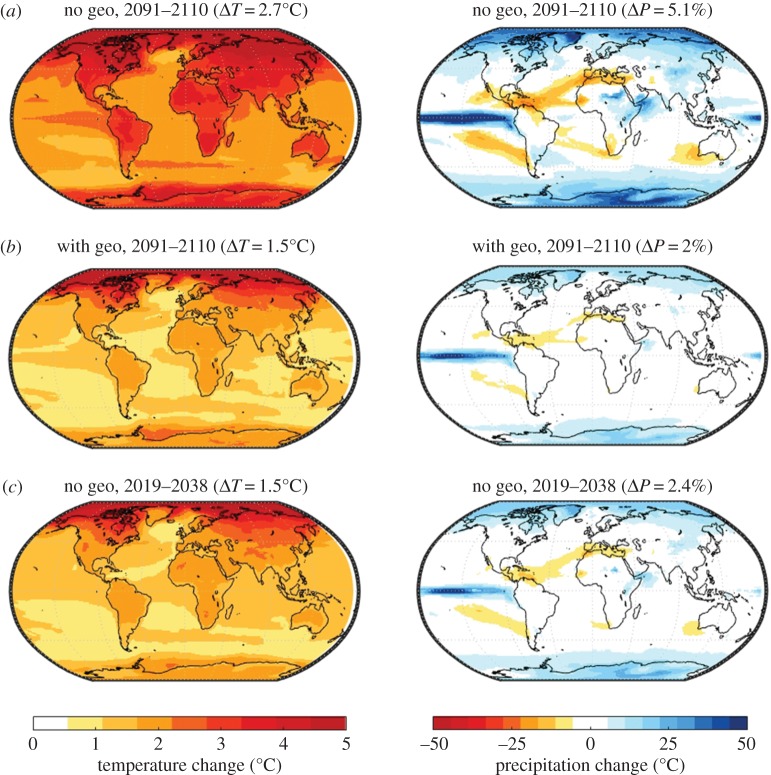

Figure 5 compares three different cases: an end-of-century (2091–2110) warming of approximately 2.7°C achieved through mitigation alone (the RCP4.5+CDR case in figures 2 and 3), the same time period but with solar geoengineering to maintain a 1.5°C target, and for comparison the average over 2019–2038 chosen so that the global mean temperature rise is 1.5°C but due only to increased GHG concentrations. The area-averaged root mean squared (RMS) temperature difference between the two 1.5°C climates is only 0.1°C, while the RMS difference between either of these and the 2.7°C climate is 1.2°C. The RMS precipitation difference between the two 1.5°C climates is 2.3%, while either 1.5°C case has approximately 8% RMS precipitation difference compared with the 2.7°C un-geoengineered climate. Electronic supplementary material, Figures S6–S8 also show the extent (or lack) of model agreement, comparing the 1.5°C-geoengineered case to either the 2.7°C no-geoengineering end-of-century case (all models show cooling everywhere), to the preindustrial (all models show warming everywhere) and to the 1.5°C case due to increased GHG alone. For this last case, the dominant difference in the geoengineered temperature pattern is the relatively cooler tropics and warmer high latitudes compared with the GHG-alone case that is an artefact of the choice of simulations used here. There is generally less model agreement for precipitation responses than for temperature (although this is also true for the CO2 warming alone).

Figure 5.

Projected temperature and precipitation changes relative to preindustrial for the scenarios in figure 2; end-of-century response without (a) and with (b) geoengineering, and for comparison the warming from 2019–2038 (c) where the global mean temperature change is 1.5°C without geoengineering. Each panel also lists the global-mean change in temperature or the % change in precipitation. Median results are shown over 12 climate models participating in GeoMIP, estimated using a dynamic climate emulator (see appendix A).

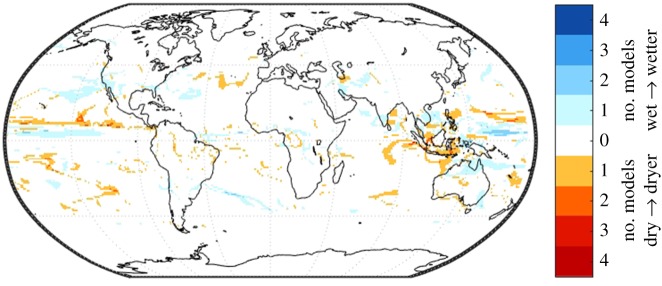

While the limited deployment of geoengineering considered here results in every location being closer to preindustrial temperature with than without geoengineering, of particular concern is whether there may be places where increased GHG leads to a reduction in precipitation that is further exacerbated by geoengineering, or where GHG leads to increased precipitation that is then increased further by geoengineering. There are places in each climate model where this is true, but these regions are not robust across climate models, as shown in figure 6, consistent with [97]. If there were less aggressive mitigation, and greater use of solar geoengineering, then there would be additional places at which the changes were statistically significant. Precipitation alone is typically not the relevant driver of climate impacts; even if precipitation were further from preindustrial in some location, reduced temperatures may still lead to a net reduction in local climate impacts. These results are from climate models, and from simulations that do not include the full physics of a specific geoengineering approach (such as SAI or MCB). One should not overinterpret these results; the only conclusion to draw without further research is that it is plausible based on current model simulations that a limited deployment in addition to mitigation could lead to a climate much more similar to a 1.5°C-climate achieved through mitigation than either is to a 3°C world.

Figure 6.

Number of models considered here (out of 12) where projected end-of-century precipitation is both further from preindustrial with geoengineering than it is without, and where the change is statistically significant over a 20-year period (consistent with the averaging time in figure 5). For temperature, every model is closer to preindustrial everywhere.

4. Summary

Solar geoengineering could be used as one element of an overall strategy to manage climate change damages and risks. Mitigation alone is unlikely to succeed in meeting a target of 1.5°C global mean temperature rise above preindustrial, with current commitments projected to lead to approximately 3°C warming. Atmospheric CDR is already built into future emissions scenarios, and over a sufficiently long term (centuries) could in principle reduce CO2 concentrations and resultant temperatures back below the 1.5°C target. In the interim, there is a potential role for solar geoengineering to limit temperature rise and associated climate changes.

Solar geoengineering with stratospheric aerosols is both certain to be able to provide at least some cooling (by analogy with large volcanic eruptions), and would be relatively straightforward technologically to implement [98]. Other approaches such as MCB or cirrus cloud thinning require more research to assess effectiveness. Simulations with climate models suggest that, while a 1.5°C-climate achieved through a combination of mitigation, CDR and solar geoengineering is not the same as a 1.5°C-climate achieved through more aggressive mitigation+CDR alone, these two are much more similar to each other than either would be to a 3°C-climate achieved through mitigation+CDR without any additional solar geoengineering. Maintaining a global mean temperature rise of 1.5°C in the presence of less aggressive mitigation would require higher levels of solar geoengineering, and would result in larger differences relative to a climate where 1.5°C was achieved without geoengineering.

From a pure climate-impacts perspective, ignoring economic and other sociopolitical factors, it is clear that achieving a 1.5°C target through emissions reduction alone would introduce fewer risks. (Though meeting this target with a combination of emissions reduction and atmospheric CDRCO2 removal would also incur impacts that also need serious evaluation.) While solar geoengineering might become the only available means of meeting the 1.5°C target, it is not yet clear whether the benefits would exceed the harms and risks from its deployment, nor, were it to be deployed, whether 1.5°C would be an appropriate goal for the deployment. Uncertainties are currently too large to support informed decisions, and more research is needed in areas such as climate impacts assessment and assessing and reducing uncertainty. There are also important factors beyond simply accounting for aggregate climate damages, including philosophical and ethical concerns, the need for centuries-long governance and concern over the impact on mitigation trajectories. However, if the 1.5°C target is exceeded it is plausible based on current climate model results that some limited amount of solar geoengineering could reduce climate damages and risks for most people.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP, the US Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provides coordinating support and led development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. We thank all participants of the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project and their model development teams, CLIVAR/WCRP Working Group on Coupled Modeling for endorsing GeoMIP, and the scientists managing the Earth System Grid data nodes who have assisted with making GeoMIP output available. We thank Lester Kwiatkowski for providing simulation data used to produce figure 3c. Paul Salazar at Cornell assisted with electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2. Conversations with Jane Long were invaluable in shaping ideas in this paper.

Appendix A

The 12 GeoMIP models used here are listed in the electronic supplementary material, Table S1. The global mean temperature response of climate models to radiative forcing is well captured by heat diffusion into a semi-infinite medium [99–101]; this is validated in electronic supplementary material, Figure S1 for the models considered here. This allows the temperature for any forcing pathway to be computed from the impulse response function (IRF) for semi-infinite diffusion. The median sensitivity of these 12 models is 3.3°C for a CO2 doubling, slightly higher than the IPCC central estimate.

The global mean precipitation response to CO2 can be decomposed into a ‘slow’ response proportional to temperature and a ‘fast’ response proportional to the instantaneous CO2 concentrations. As in [102], we fit the precipitation response of the GeoMIP models to

where T is the global mean temperature, fCO2 the radiative forcing from CO2, S>0 the solar reduction and the coefficients α>0, β<0 and γ>0 are found from least squares, shown in electronic supplementary material, Figure S2 for each model. Electronic supplementary material, Figure S3 verifies that this functional form reasonably predicts precipitation changes in the GeoMIP models.

Aragonite saturation of the surface ocean is determined primarily by atmospheric CO2 concentrations, but is also sensitive to temperature [94]; the tropical aragonite saturation state is approximated as

The temperature sensitivity is difficult to capture in simulations without solar geoengineering because of the high correlation between CO2 and temperature. Simulations of RCP4.5 both with and without solar geoengineering [94] in a model with dynamic ocean biogeochemistry (HadGEM-ES) were used to derive the temperature coefficient after controlling for atmospheric CO2. That relationship was then applied to the ensemble median response of ΩA to changes in atmospheric CO2 using the full ensemble of CMIP5 simulations that included dynamic ocean biogeochemistry (see [103] for the list of simulations included).

To estimate the regional response for each model, the emulator in [43] first computes empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs) from the abrupt 4×CO2 and GeoMIP G1 simulations. (G1 balances the 4×CO2 temperature using solar reduction.) The first EOF captures the spatial pattern of the long-term response to increased CO2, while the next few EOFs describe both differences between the short- and long-term response to forcing and differences between the response to solar reduction and CO2 forcing. Only the first three to four EOFs typically have any predictive power; higher EOFs simply describe natural variability in the simulations used to train the emulator.

As with the global-mean temperature, the response to any forcing scenario can be computed from the IRF, assuming linearity. An assumption-free IRF can be estimated for the projection onto each EOF as the time-derivative of the corresponding 4×CO2 response [43]. There is some uncertainty in the IRF due to natural variability in the 4×CO2 simulation, but the resulting errors are small when projecting the response to smaller CO2 levels. We fit the IRF for the projection onto the first EOF to semi-infinite diffusion as above, including a fit to the fast response for precipitation. This is necessary as the assumption-free IRF estimates are limited to the duration of the training simulations. The IRFs for the projections onto the second and higher EOFs decay to zero before the end of the simulations and can be set to zero thereafter. The projected forced response is the sum of the responses for each EOF.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by Cornell University’s David R. Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future.

References

- 1.UNFCCC. 2015. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. See https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09.pdf.

- 2.Rogelj J, Luderer G, Pietzcker RC, Kriegler E, Schaeffer M, Krey V, Riahi K. 2015. Energy system transformations for limiting end-of-century warming to below 1.5°C. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 519–527. ( 10.1038/nclimate2572) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanderson B, O’Neill B, Tebaldi C. 2016. What would it take to achieve the Paris temperature targets? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7133–7142. ( 10.1002/2016GL069563) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogelj J. et al. 2016. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature 534, 631–639. ( 10.1038/nature18307) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academy of Sciences. 2015. Climate intervention: carbon dioxide removal and reliable sequestration. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuss S. et al. 2014. Betting on negative emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 850–853. ( 10.1038/nclimate2392) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockström J. et al. 2016. The world’s biggest gamble. Earth’s Future 4, 465–470. ( 10.1002/2016EF000392) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field CB, Mach KJ. 2017. Rightsizing carbon dioxide removal. Science 356, 706–707. ( 10.1126/science.aam9726) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricke KL, Millar RJ, MacMartin DG. 2017. Constraints on global temperature target overshoot. Sci. Rep. 7, 14743 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-14503-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long JCS, Shepherd JG. 2014. The strategic value of geoengineering research. Glob. Environ. Change 1, 757–770. ( 10.1007/978-94-007-5784-4_24) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wigley TML. 2006. A combined mitigation/geoengineering approach to climate stabilization. Science 314, 452–454. ( 10.1126/science.1131728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith SJ, Rasch PJ. 2013. The long-term policy context for solar radiation management. Clim. Change 121, 487–497. ( 10.1007/s10584-012-0577-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long JCS. 2017. Coordinated action against climate change: a new world symphony. Issues. Sci. Technol. 33, Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crutzen PJ. 2006. Albedo enhancement by stratospheric sulfur injections: a contribution to resolve a policy dilemma? Clim. Change 77, 211–219. ( 10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latham J. et al. 2012. Marine cloud brightening. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 370, 4217–4262. ( 10.1098/rsta.2012.0086) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angel R. 2006. Feasibility of cooling the Earth with a cloud of small spacecraft near the inner Lagrange point (L1). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17 184–17 189. ( 10.1073/pnas.0608163103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irvine PJ, Ridgwell A, Lunt DJ. 2011. Climatic effects of surface albedo geoengineering. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 116, D24112 ( 10.1029/2011JD016281) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crook JA, Jackson LS, Forster PM. 2016. Can increasing albedo of existing ship wakes reduce climate change? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 1549–1558. ( 10.1002/2015JD024201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell DL, Finnegan W. 2009. Modification of cirrus clouds to reduce global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 045102 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/045102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penner JE, Zhou C, Liu X. 2015. Can cirrus cloud seeding be used for geoengineering? Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8775–8782. ( 10.1002/2015GL065992) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robock A. 2008. 20 reasons why geoengineering may be a bad idea. Bull. Atom. Sci. 64, 14–18. ( 10.1080/00963402.2008.11461140) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keith DW, MacMartin DG. 2015. A temporary, moderate and responsive scenario for solar geoengineering. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 201–206. ( 10.1038/nclimate2493) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins M. et al. 2013. Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. In Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds TF Stocker, D Qin, GK Plattner, M Tignor, S Allen, J Boschung, A Nauels, Y Xia, V Bex, P Midgley), pp. 1029–1136. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 24.Matthews HD, Landry JS, Partanen AI, Allen M, Eby M, Forster PM, Friedingstein P, Zickfeld K. 2017. Estimating carbon budgets for ambitious climate targets. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 3, 69–77. ( 10.1007/s40641-017-0055-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knutti R, Rogelj J, Sedláček J, Fischer EM. 2016. A scientific critique of the two-degree climate change target. Nature Geosci. 9, 13–18. ( 10.1038/ngeo2595) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keith DW, Irvine PJ. 2016. Solar geoengineering could substantially reduce climate risks—A research hypothesis for the next decade. Earth’s Future 4, 549–559. ( 10.1002/2016EF000465) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack CG. et al. 2016. Key impacts of climate engineering on biodiversity and ecosystems, with priorities for future research. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 13, 103–128. ( 10.1080/1943815X.2016.1159578) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacMartin DG, Kravitz B, Long JCS, Rasch PJ. 2016. Geoengineering with stratospheric aerosols: what don’t we know after a decade of research? Earth’s Future 4, 543–548. ( 10.1002/2016EF000418) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith DW. 2017. Toward a responsible solar geoengineering research program. Issues Sci. Technol. 33, Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schäfer S. et al 2015. The European Transdisciplinary Assessment of Climtae Engineering (EuTRACE): removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and reflecting sunlight away from Earth. EuTRACE Report.

- 31.Horton J, Keith D. 2016. Solar geoengineering and obligations to the global poor. In Climate justice and geoengineering: ethics and policy in the atmospheric anthropocene (ed. CJ Preston), pp. 79–92. London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- 32.Parson EA, Ernst LN. 2013. International governance of climate engineering. Theor. Inquiries Law 14, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodansky D. 2013. The who, what, and wherefore of geoengineering governance. Clim. Change 121, 539–551. ( 10.1007/s10584-013-0759-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett S. 2014. Solar geoengineering’s brave new world: thoughts on the governance of an unprecedented technology. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 8, 249–269. ( 10.1093/reep/reu011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton JB, Reynolds JL. 2016. The international politics of climate engineering: a review and prospectus for international relations. Int. Stud. Rev. 18, 438–461. ( 10.1093/isr/viv013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morton O. 2015. The planet remade: how geoengineering could change the world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frumhoff PC, Stephens JC. 2018. Towards legitimacy of the solar geoengineering research enterprise. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20160459 ( 10.1098/rsta.2016.0459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caldeira K, Bala G, Cao L. 2013. The science of geoengineering. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 41, 231–256. ( 10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105548) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robock A. 2014. Stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Issues Environ. Sci. and Tech. 38, 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Academy of Sciences. 2015. Climate intervention: reflecting sunlight to cool Earth. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irvine PJ, Kravitz B, Lawrence MG, Muri H. 2016. An overview of the Earth system science of solar geoengineering. WIREs Clim. Change 7, 815–833. ( 10.1002/wcc.423) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tilmes S, Sanderson BM, O’Neill B. 2016. Climate impacts of geoengineering in a delayed mitigation scenario. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8222–8229. ( 10.1002/2016GL070122) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacMartin DG, Kravitz B. 2016. Dynamic climate emulator for solar geoengineering. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 15 789–15 799. ( 10.5194/acp-16-15789-2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kravitz B, Robock A, Boucher O, Schmidt H, Taylor KE, Stenchikov G, Schulz M. 2011. The Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). Atmos. Sci. Lett. 12, 162–167. ( 10.1002/asl.316) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kravitz B. et al. 2013. Climate model response from the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). J. Geophys. Res. 118, 8320–8332. ( 10.1002/JGRD.50646) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Govindasamy B, Caldeira K. 2000. Geoengineering Earth’s radiation balance to mitigate CO2-induced climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 2141–2144. ( 10.1029/1999GL006086) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferraro AJ, Charlton-Perez AJ, Highwood EJ. 2015. Stratospheric dynamics and midlatitude jets under geoengineering with space mirrors and sulfate and titania aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. A 120, 414–429. ( 10.1002/2014JD022734) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrews T, Forster PM, Boucher O, Bellouin N, Jones A. 2010. Precipitation, radiative forcing and global temperature change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L14701 ( 10.1029/2010GL043991) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao L, Bala G, Caldeira K. 2012. Climate response to changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide and solar irradiance on the time scale of days to weeks. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 034015 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bala G, Duffy PB, Taylor KE. 2008. Impact of geoengineering schemes on the global hydrological cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7664–7669. ( 10.1073/pnas.0711648105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tilmes S. et al. 2013. The hydrological impact of geoengineering in the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). J. Geophys. Res. 118, 11 036–11 058. ( 10.1002/jgrd.50868) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niemeier U, Schmidt H, Alterskjær K, Kristjánsson JE. 2013. Solar irradiance reduction via climate engineering: impact of different techniques on the energy balance and the hydrological cycle. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 118, 11 905–11 917. ( 10.1002/2013JD020445) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalidindi S, Bala G, Modak A, Caldeira K. 2015. Modeling of solar radiation management: a comparison of simulations using reduced solar constant and stratospheric sulphate aerosols. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2909–2925. ( 10.1007/s00382-014-2240-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crook JA, Jackson LS, Osprey SM, Forster PM. 2015. A comparison of temperature and precipitation responses to different Earth radiation management geoengineering schemes. J. Geophys. Res. A. 120, 9352–9373. ( 10.1002/2015JD023269) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tilmes S, Richter JH, Mills MJ, Kravitz B, MacMartin DG, Vitt F, Tribbia JJ, Lamarque JF. 2017. Sensitivity of aerosol distribution and climate response to stratospheric SO2 injection locations. J. Geophys. Res. A. 122, 12 591–12 615. ( 10.1002/2017JD026888) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai Z, Weisenstein D, Keith DW. 2018. Tailoring meridional and seasonal radiative forcing by sulfate aerosol solar geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1030–1039. ( 10.1002/2017GL076472) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kravitz B, MacMartin DG, Mills MJ, Richter JH, Tilmes S, Lamarque JF, Tribbia JJ, Vitt F. 2017. First simulations of designing stratospheric sulfate aerosol geoengineering to meet multiple simultaneous climate objectives. J. Geophys. Res. A 122, 12 616–12 634. ( 10.1002/2017JD026874) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haywood JM, Jones A, Bellouin N, Stephenson D. 2013. Asymmetric forcing from stratospheric aerosols impacts Sahelian rainfall. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 660–665. ( 10.1038/nclimate1857) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ban-Weiss GA, Caldeira K. 2010. Geoengineering as an optimization problem. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 034009 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/5/3/034009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacMartin DG, Keith DW, Kravitz B, Caldeira K. 2013. Management of trade-offs in geoengineering through optimal choice of non-uniform radiative forcing. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 365–368. ( 10.1038/nclimate1722) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kravitz B, MacMartin DG, Wang H, Rasch PJ. 2016. Geoengineering as a design problem. Earth Syst. Dyn. 7, 469–497. ( 10.5194/esd-7-469-2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MacMartin DG, Kravitz B, Tilmes S, Richter JH, Mills MJ, Lamarque JF, Tribbia JJ, Vitt F. 2017. The climate response to stratospheric aerosol geoengineering can be tailored using multiple injection locations. J. Geophys. Res. A 122, 12 574–12 590. ( 10.1002/2017JD026868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pitari G, Genova GD, Mancini E, Visioni D, Gandolfini I, Cionni I. 2016. Stratospheric aerosols from major volcanic eruptions: a composition-climate model study of the aerosol cloud dispersal and e-folding time. Atmosphere 7, 75 ( 10.3390/atmos7060075) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aquila V, Garfinkel CI, Newman PA, Oman LD, Waugh DW. 2014. Modifications of the quasi-biennial oscillation by a geoengineering perturbation of the stratospheric aerosol layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1738–1744. ( 10.1002/2013GL058818) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richter JH, Tilmes S, Mills MJ, Tribbia JJ, Kravitz B, Vitt F, Lamarque JF. 2017. Stratospheric dynamical response and ozone feedbacks in the presence of SO2 injection. J. Geophys. Res. A 122, 12 557–12 573. ( 10.1002/2017JD026912) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tilmes S, Müller R, Salawitch R. 2008. The sensitivity of polar ozone depletion to proposed geoengineering schemes. Science 320, 1201–1204. ( 10.1126/science.1153966) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pitari G. et al. 2014. Stratospheric ozone response to sulfate geoengineering: results from the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). J. Geophys. Res. A 119, 2629–2653. ( 10.1002/2013JD020566) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Solomon S, Rosenlof KH, Portmann RW, Daniel JS, Davis SM, Sanford TJ, Plattner GK. 2010. Contributions of stratospheric water vapor to decadal changes in the rate of global warming. Science 327, 1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aquila V, Oman LD, Stolarski RS, Douglass AR, Newman PA. 2013. The response of ozone and nitrogen dioxide to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo at southern and norther midlatitudes. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 894–900. ( 10.1175/JAS-D-12-0143.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xia L, Nowack PJ, Tilmes S, Robock A. 2017. Impacts of stratospheric sulfate geoengineering on tropospheric ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 11 913–11 928. ( 10.5194/acp-17-11913-2017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dykema JA, Keith DW, Keutsch FN. 2016. Improved aerosol radiative properties as a foundation for solar geoengineering risk assessment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7758–7766. ( 10.1002/2016GL069258) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keith DW, Weisenstein KK, Dykema JA, Keutsch FN. 2016. Stratospheric solar geoengineering without ozone loss? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14 910–14 914. ( 10.1073/pnas.1615572113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stenke A, Schraner M, Rozanov E, Egorova T, Luo B, Peter T. 2013. The SOCOL version 3.0 chemistry-climate model: description, evaluation, and implications from an advanced transport algorithm. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 1407–1427. ( 10.5194/gmd-6-1407-2013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mills M. et al. 2017. Radiative and chemical response to interactive stratospheric aerosols in fully coupled CESM1(WACCM). J. Geophys. Res. A. 122, 13 061–13 078. ( 10.1002/2017JD027006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keith DW, Duren R, MacMartin DG. 2014. Field experiments on solar geoengineering: report of a workshop exploring a representative research portfolio. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 372, 20140175 ( 10.1098/rsta.2014.0175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dykema JA, Keith DW, Anderson JG, Weisenstein D. 2014. Stratospheric-controlled perturbation experiment: a small-scale experiment to improve understanding of the risks of solar geoengineering. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 372, 20140059 ( 10.1098/rsta.2014.0059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robock A, MacMartin DG, Duren R, Christensen MW. 2013. Studying geoengineering with natural and anthropogenic analogs. Clim. Change 121, 445–458. ( 10.1007/s10584-013-0777-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wood R, Ackerman TP. 2013. Defining success and limits of field experiments to test geoengineering by marine cloud brightening. Clim. Change 121, 459–472. ( 10.1007/s10584-013-0932-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wood R, Ackerman T, Rasch P, Wanser K. 2017. Could geoengineering research help answer one of the biggest questions in climate science? Earth’s Future 4, 659–663. ( 10.1002/2017EF000601) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malavelle FF. et al. 2017. Strong constraints on aerosol–cloud interactions from volcanic eruptions. Nature 546, 485–491. ( 10.1038/nature22974) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.MacMynowski DG, Keith DW, Caldeira K, Shin HJ. 2011. Can we test geoengineering? Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 5044–5052. ( 10.1039/C1EE01256H) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.MacMartin DG, Kravitz B, Rasch PJ. 2015. On solar geoengineering and climate uncertainty. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7156–7161. ( 10.1002/2015GL065391) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.MacMartin DG, Kravitz B, Keith DW, Jarvis AJ. 2014. Dynamics of the coupled human-climate system resulting from closed-loop control of solar geoengineering. Clim. Dyn. 43, 243–258. ( 10.1007/s00382-013-1822-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burns ET, Flegal JA, Keith DW, Mahajan A, Tingley D, Wagner G. 2016. What do people think when they think about solar geoengineering? a review of empirical social science literature, and prospects for future research. Earth’s Future 4, 536–542. ( 10.1002/2016EF000461) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meinshausen M. et al. 2011. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extension from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Change 109, 213–241. ( 10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keith DW, Wagner G, Zabel CL. 2017. Solar geoengineering reduces atmospheric carbon burden. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 617–619. ( 10.1038/nclimate3376) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomson AM. et al. 2011. Rcp4.5: a pathway for stabilization of radiative forcing by 2100. Clim. change 109, 77 ( 10.1007/s10584-011-0151-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clarke L. et al. 2014. Assessing transformation pathways. In Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds O Edenhofer et al.), pp. 417–510. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 89.Cao L, Caldeira K. 2010. Atmospheric carbon dioxide removal: long-term consequences and commitment. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 024011 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/5/2/024011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Azar C, Johansson DJA, Mattson N. 2013. Meeting global temperature targets–the role of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034004 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kato E, Yamagata Y. 2014. BECCS capability of dedicated bioenergy crops under a future land-use scenario targeting net negative carbon emissions. Earth’s Future 2, 421–439. ( 10.1002/2014EF000249) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith P. et al. 2016. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50. ( 10.1038/nclimate2870) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boysen LR, Lucht W, Gerten D, Heck V, Lenton TM, Schellnhuber HJ. 2017. The limits to global-warming mitigation by terrestrial carbon removal. Earth’s Future 5, 463–474. ( 10.1002/2016EF000469) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kwiatkowski L, Cox P, Halloran PR, Mumby PJ, Wiltshire AJ. 2015. Coral bleaching under unconventional scenarios of climate warming and ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 777–781. ( 10.1038/nclimate2655) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pongratz J, Lobell DB, Cao L, Caldeira K. 2012. Crop yields in a geoengineered climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 101–105. ( 10.1038/nclimate1373) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pierce JR, Weisenstein DK, Heckendorn P, Peter T, Keith DW. 2010. Efficient formation of stratospheric aerosol for climate engineering by emission of condensible vapor from aircraft. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L18805 ( 10.1029/2010GL043975) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kravitz B. et al. 2014. A multi-model assessment of regional climate disparities caused by solar geoengineering. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 074013 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/9/7/074013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McClellan J, Keith DW, Apt J. 2012. Cost analysis of stratospheric albedo modification delivery systems. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 034019 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.MacMynowski DG, Shin HJ, Caldeira K. 2011. The frequency response of temperature and precipitation in a climate model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L16711 ( 10.1029/2011GL048623) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Caldeira K, Myhrvold N. 2013. Projections of the pace of warming following an abrupt increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. Environ. Res. Lett. 8 034039 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034039) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.MacMartin DG, Caldeira K, Keith DW. 2014. Solar geoengineering to limit rates of change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 372, 20140134 ( 10.1098/rsta.2014.0134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cao L, Bala G, Zheng M, Caldeira K. 2015. Fast and slow climate responses to CO2 and solar forcing: a linear multivariate regression model characterizing transient climate change. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 12 037–12 053. ( 10.1002/2015JD023901) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ricke KL, Orr JC, Schneider K, Caldeira K. 2013. Risks to coral reefs from ocean carbonate chemistry changes in recent earth system model projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 8 034003 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.