Abstract

Background:

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein families are a large class of transcription factors, which are associated with cell proliferation, tissue differentiation, and other important development processes. We reported that the Nuclear localized protein-1 (Nulp1) might act as a novel bHLH transcriptional factor to mediate cellular functions. However, its role in development in vivo remains unknown.

Methods:

Nulp1 (dNulp1) mutants are generated by CRISPR/Cas9 targeting the Domain of Unknown Function (DUF654) in its C terminal. Expression of Wg target genes are analyzed by qRT-PCR. We use the Top-Flash luciferase reporter assay to response to Wg signaling.

Results:

Here we show that Drosophila Nulp1 (dNulp1) mutants, generated by CRISPR/Cas9 targeting the Domain of Unknown Function (DUF654) in its C terminal, are partially homozygous lethal and the rare escapers have bent femurs, which are similar to the major manifestation of congenital bent-bone dysplasia in human Stuve-Weidemann syndrome. The fly phenotype can be rescued by dNulp1 over-expression, indicating that dNulp1 is essential for fly femur development and survival. Moreover, dNulp1 overexpression suppresses the notch wing phenotype caused by the overexpression of sgg/GSK3β, an inhibitor of the canonical Wnt cascade. Furthermore, qRT-PCR analyses show that seven target genes positively regulated by Wg signaling pathway are down-regulated in response to dNulp1 knockout, while two negatively regulated Wg targets are up-regulated in dNulp1 mutants. Finally, dNulp1 overexpression significantly activates the Top-Flash Wnt signaling reporter.

Conclusion:

We conclude that bHLH protein dNulp1 is essential for femur development and survival in Drosophila by acting as a positive cofactor in Wnt/Wingless signaling.

Keywords: bHLH, dNulp1, CRISPR/Cas9, Wnt/Wg signaling, femur, Drosophila

1. INTRODUCTION

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein families are a large class of transcription factors, including myf-5, MyoD, twist, ehand, and dhand [1-3], which are associated with neurogenesis, muscle cell specification and differentiation, cell proliferation, tissue differentiation, and other important development process [4]. bHLH family members form homodimers or heterodimers to activate or repress target gene expression [5, 6]. The function of bHLH families are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to humans [7].

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a critical role in tissue development [8, 9]. This pathway was first described in Drosophila, where the homologue of the Wnt ligand is encoded by the wingless (wg) gene. Downstream, armadillo (arm), the homologue of mammalian β-Catenin, is a critical intracellular mediator in Wg signaling [10]. Canonical Wg signaling is initiated when Wg binds to frizzled/lipoprotein receptors to form heterodimers, which promotes stabilization and accumulation of cytosolic Arm. Subsequently Arm translocates to the nucleus, where it binds the DNA-binding protein T-cell factor (TCF), pangolin (Pan) in Drosophila, lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) and other cofactors to form a complex that controls the transcription of Wg/TCF responsive genes [11]. Most of the Wnt pathway components are evolutionarily conserved between Drosophila and humans.

Wg, a homolog of mammalian Wnt1, is essential for the development of all fly appendages [12, 13]. Sol narae (Sona), a Drosophila ADAMTS involved in Wg signaling, causes malformed appendages in the loss-of-function mutants, such as missing and malformed branches of arista, disrupted ommatidial bristles, bent femurs, and smaller wings with disordered veins [14]. Two segment polarity genes in Drosophila, legless (lgs) and pygopus (pygo), are also involved in Wnt signaling. Lgs and pygo mutant flies display a segment polarity phenotype and in the pygo mutant, a row of bristles on the ventral side of the leg is missing [15].

Stuve-Weidemann syndrome (STWS) is a rare congenital disorder in human with the major manifestation being bowing of the long bones (particularly the tibia and the femur) (OMIM #601559) and with frequent deaths in infancy [16]. The leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) gene is considered to be the causative gene of the disease [16]. Loss of the LIFR gene in mice results in a phenotype similar to that of human STWS [17]. However, the mutations in the LIFR gene are found in only some patients with STWS. Other causative genes for STWS remain to be identified [16].

Nulp1 has been isolated and identified as a novel bHLH gene and it may participate in the regulation of cellular functions [18]. Nulp1 homologues exist in many species from invertebrates to vertebrates, including human, rat, mouse, Danio, C. elegans and Drosophila melanoganster. It is known that TCF/Pan/LEF interact with other cofactors to form a complex that affects the transcription of Wg/TCF responsive genes [19]. Here we used the fly model to explore the in vivo function of Nulp1 and test the possibility that Nulp1 may act as a co-factor in Wnt/Wg signaling.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fly Stocks and Maintenance

All Fly strains used in this study were maintained on standard cornmeal food (Bloomington formulation) at 25°C. The nos-CAS9 fly stocks (Cas9 express in Germ cell) were a gift from Xingjie Ren, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China. The 3rd chromosome balancer stock (TM3/TM6B-ubi-GFP and TM3/TM6B), Arm-Gal4, and salE-Gal4 were a gift from Rolf Bodmer, Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute. Wildtype (WT) and UAS-Sgg (5360) flies were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center at Indiana University, USA.

2.2. DNA Constructs

We obtained gRNA oligo nucleotides from Sangon Biological, Shanghai, China. gRNA oligo nucleotides contained Bbs I cohesive ends (sgRNA oligo forward: 5’-TTCGGTTCAAGCACGCGCAGTACC-3’; sgRNA oligo reverse: 5’-AAACGTTCAAGCACGCGCAGTACC-3’). The annealed gRNA oligo nucleotides were then cloned into the pCFD3: U6:3-gRNA plasmid (Addgene, China, #49410). dNulp1-PA cDNA was originally obtained from a fly embryo cDNA library (see below). dNulp1-PA cDNA was cloned into the pMD18-T vector. The pUAST-dNulp1 was generated by tagging dNulp1-PA downstream of 5×Gal4 binding sites in pUAST using EcoRI and KpnI. pAct-dNulp1 was generated by tagging dNulp1-PA into the multiple cloning site using speI and KpnI.

2.3. Embryo Injections and Mutant Strains Screening

Embryo injections were provided by Core Facility of Drosophila Resource and Technology, SIBCB, CAS (Shanghai, China). In brief, the injection mix contained 50 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and sgRNA plasmid (final concentration 300ng/µl. Embryos were collected from a 30 min egg-laying period with nos-cas9 flies. Egg chorion was removed by incubating hypochlorite in 30% sodium for 2 min. After the eggs dried, they were injected into posterior pole with the injection mix, then cultured in a moist chamber at 18°C for 36 to 48 h. Approximately 50 larvae were collected into vials and incubated at 25°C. All F0 flies were crossed to the 3rd chromosome balancer stock (TM3/TM6B-ubi-GFP). Ten F1 flies with TM6B-ubi-GFP were collected to extract genome for HRMA (High resolution melting analysis). The fly lines with different melting curves compared with wt control were crossed to the 3rd chromosome balancer stock. Then ten F2 flies with TM6B-ubi-GFP were collected for HRMA, and the lines with different melting curves compared with wt control were inbred to obtain F3 progeny with the TM6B-ubi-GFP marker. Extracted genomic DNA from F3 flies was analyzed by PCR and direct sequencing (Fig. S1 (248.9KB, pdf) ).

2.4. Genomic DNA Extraction, PCR Analysis and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from 10 adult flies by the gDNA Mini Tissue kit (Invitrogen, Cat. no. CS11204) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. A typical PCR (20 µl) contained 0.5 µM of each primer (cas-bves-F/ cas-bves-R), 1µl gDNA, 10µl 2X PCR mix (Biotool, Cat. no. B46015), and 7µl ddH2O. PCR conditions were 95°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec, and a final elongation at 72°C for 8 min, then held at 4°C. PCR production was purified by the Cycle-pure kit (OMEGA, Cat. no. D6492-02) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. 180bp PCR product was amplified spanning the presumed CRISPR cleavage site (F primers: 5’- TTCTCCTTCTGGAATCGT-3’; R primers: 5’-GACTCAGGAGCAGTTTGG -3’). Purified PCR product was then cloned into PMD18-T vector (TaKaRa, Cat. no. 6011). Sequencing was carried out by BioSune (Shanghai, China). Sequence analysis was done with BLAST.

2.5. Total RNA Extraction, Real-Time q-PCR Analysis

Real-time q-PCR analyses was carried out with SYBR Green premix ExTaq™ II (TaKaRa, Cat. no. RR820A) on the QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from 10 larvae using the RNA Isolation Kit from Sigma-Aldrich (Canada, #83913) according to the manufacture's protocol and reverse transcribed with cDNA Synthesis Kits (TaKaRa), followed by qRT-PCR. Sequences of the primer pairs used are listed in Table S1 (248.9KB, pdf) .

2.6. Total Protein Extraction, Antibody, Western Analysis

Total protein was extracted from 100 fly embryos using 50µl RIPA buffer (AuRAGENE, Cat. no. P002A) and 1µl cocktail (Biotool, Cat. no. B14001). For Western analysis, samples were mixed with 5 x loading buffer and boiled at 95°C for 10 min. Samples were then separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred, membranes were blocked with 8% nonfat milk in TBST buffer (10 mMTris pH 7.4, 0.8% NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20). Primary antibodies were directed against the dNulp1 (1:2,000), and β-actin (1:2,000, Sigma). Secondary antibodies were anti-rat IgG (1:2,000; Sigma) or anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; Sigma). Proteins were visualized using the Super Signal West Dura detection reagent (Thermo Scientific) and signals were detected with the ChemiGenius Bio Imaging System.

2.7. Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay

S2 cells (1x105) were transfected with a total of 300ng of various plasmid combinations (1:3 ratio of reporter plasmid to renilla). Luciferase activities of the plasmid Top-Flash was measured 48h after stimulation with pActin-nulp1 using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The basal activity of WNT/β-catenin signaling corresponds to the negative control where only pAct-back, pAct-dNulp1, TOP-flash, or pAct+ TOP-flash were transfected. Every experiment was repeated at least twice with three replicates in each independent experiment.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 Software. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t test; p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. dNulp1 is Involved in Wnt Signaling Cascade

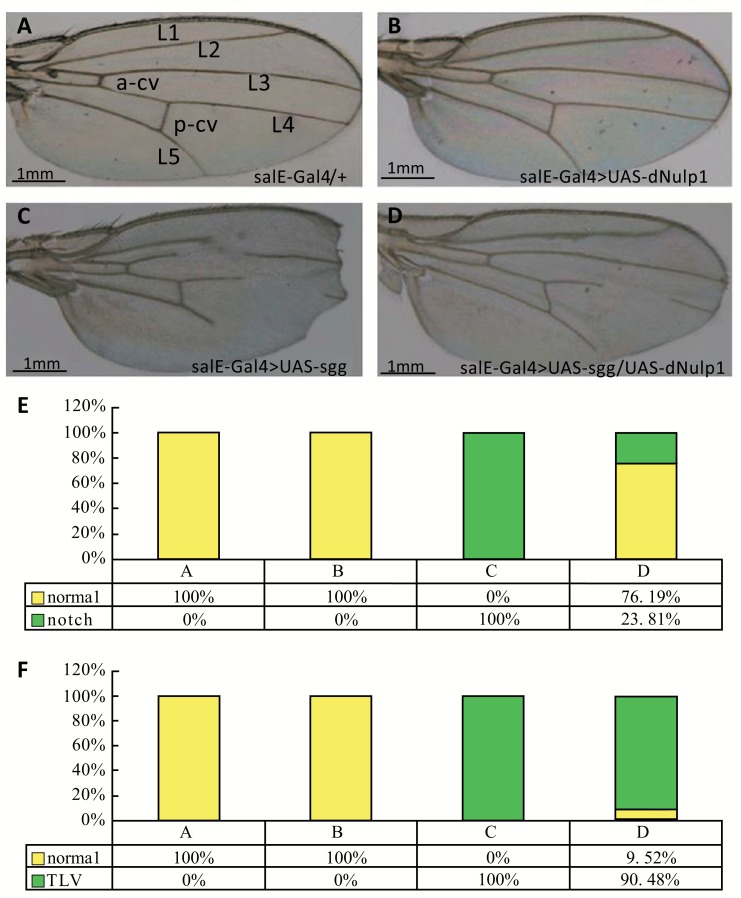

Sgg, also known as Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3β), is a key component of the β-catenin destruction complex. It functions as an inhibitor of the canonical Wnt signaling cascade [20, 21]. Whereas, WT flies and flies with over-expression of dNulp1 using the salE-Gal4 driver in wing disc showed normal wing phenotype (Fig. 1A-B). We over-expressed Sgg using the salE-Gal4 driver, which would be expected to block wingless signaling [22]. As expected, these flies displayed some notch phenotypes and mismatched veins in the wing (Fig. 1C). The notch phenotype induced by sgg overexpression was rescued by co-over-expression of dNulp1 and the mismatched longitudinal vein phenotype was also largely rescued except for some defects in L4 (the forth longitudinal vein) (Fig. 1D-F). These results indicate that dNulp1 is involved in the Wnt signaling cascade.

Fig. (1).

Ectopic expression of dNulp1 in the wing rescues the wing notch defects caused by the sgg over-expression. (A) The wing of a male fly from the salE-Gal4 line crossed with WT line (control); longitudinal (L1 to L5) and cross veins (a-cv, p-cv) are indicated. N=20. (B) dNulp1 over-expression (salE-GAL4>UAS-dNulp1) resulted in a normal wing phenotype; N=20. (C) sgg over-expression in the wing (salE-GAL4>UAS-sgg) caused wing defects, including notches in the wing margin (arrows), and L2 to L5 are truncated (asterisk). N=20. (D) Co-overexpression of dNulp1 along with sgg rescued the notched wing and partially rescued the truncated longitudinal veins (TLV, except for L4) phenotypes, and restored the wing notch defects in salE-GAL4>UAS-sgg. N=21. All scale bars are 1 mm. (E) Percentage of normal, and notch wing phenotypes in the different genotypes. 76.19% of flies’ notch wing were rescued by dNulp1 over-expression. (F) Percentage of normal, and TLV wing in the different genotypes. Only 9.52% of flies’ TLV wing were rescued by dNulp1 over-expression.

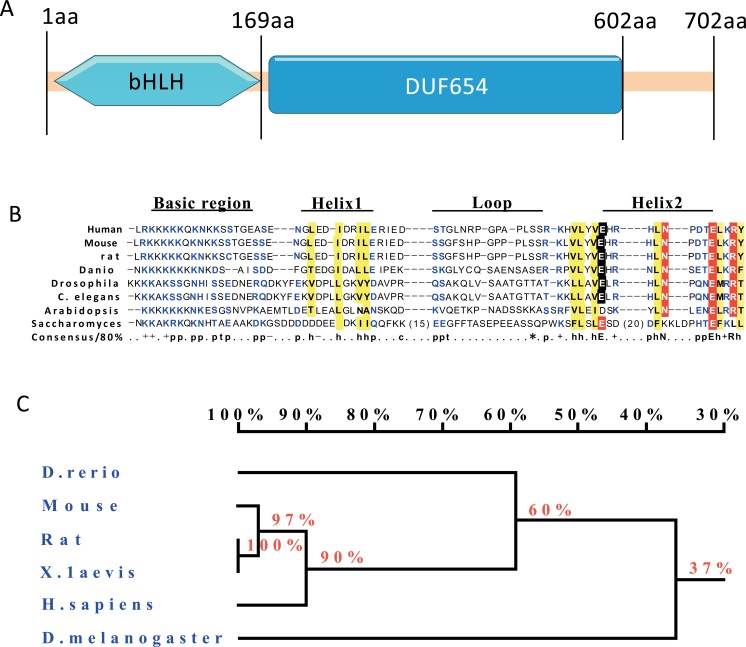

3.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of Drosophila Nulp1

The Nulp1 homolog in Drosophila melanogaster is dNulp1, also known as CG7927 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene), inferred from sequence or structural similarity with human Nulp1/TCF25. dNulp1 is located on the left arm of the third chromosome (3L), in the region 66B6-66B6 (8,110,368..8,113,406) and its genomic sequence has 7 exons separated by 6 introns, with 3 different transcripts identified as dNulp1-PA, dNulp1-PB and dNulp1-PC. dNulp1 has a bHLH domain in the N-terminus and a domain of unknown function called DUF654 in the C-terminus (Fig. 2A). The dNulp1 protein in Drosophila shares a high degree of homology with other Nulp1 proteins, especially in bHLH domain and DUF654 domain (Fig. 2B-C).

Fig. (2).

Comparison of the amino acid sequences among known Nulp1 proteins. (A) dNulp1 has the bHLH domain in N-terminal and a domain of unknown function called DUF654 in C-terminal. (B) A comparison of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) motif to other known bHLH in Nulp1proteins. Amino acids in blue and red indicate residues that match the consensus sequence for bHLH sequences. Amino acids in yellow indicate conservative substitutions. (C) Homology Tree: A comparison of the Nulp1 amino acid sequence in fly to known Nulp1 proteins from other species, showing a 37% amino acid conservation between fly and human. (Color figure available online).

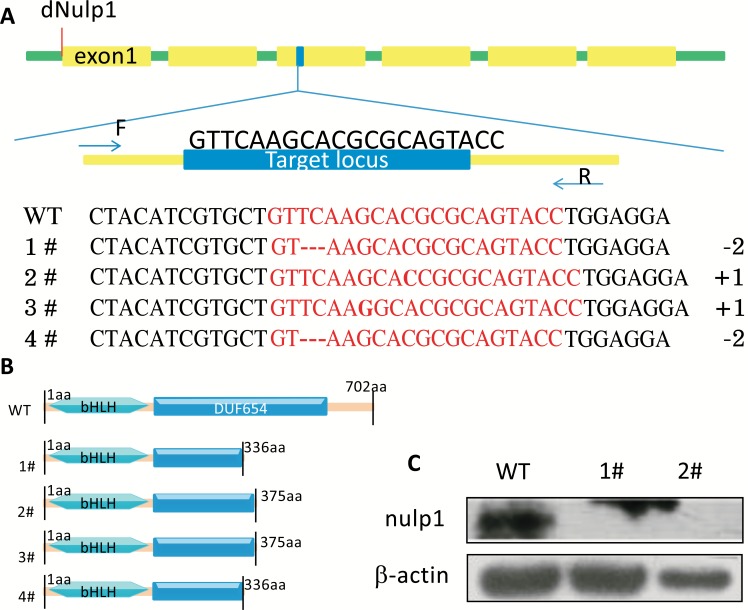

3.3. CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated dNulp1 Knockout in D. melanogaster

We used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to obtain the dNulp1 knockout flies. We chose to target a region located in the third exon of dNulp1 (on-target locus 3L: 8111649-8111671), with the sequence GTTCAAGCACGCGCAGTACC (Fig. 3A). We assembled this 20bp sgRNA oligos into a vector pCFD3-dU6:3gRNA and injected the sgRNA plasmid into approximately 200 nos-CAS9 fly embryos. Approximately 25% of injected embryos (40) survived as F0 flies, and they were crossed to a balancer stock (TM3/TM6B-ubi-GFP) (Fig. S1 (248.9KB, pdf) ). 34 of those F0 crosses produced viable offspring (~85%). F1 progeny was collected and genomic DNA was extracted for High Resolution Melting Assay (HRMA) [23] and four clusters showed different melting curves compared with WT. Then each F1 fly was crossed to a balancer stock (TM3/TM6B-ubi-GFP) (Fig. S1 (248.9KB, pdf) ). F2 progenies were collected and gDNA extracted for a second HRMA, and four different clusters with different melting curves compared with WT control were observed. Finally, the four different F2 fly lines with TM6B-ubi-GFP were interbred to obtain F3 progeny with the TM6B-ubi-GFP marker. Extracted genomic DNA from F3 flies was analyzed by PCR and direct sequencing. The result showed 4 lines with indel mutations; lines dNulp11# and dNulp14# exhibited the same mutation, 2bp deletions at 1007-1008bp in the CDS of dNulp1. dNulp12# had 1bp insertion at the 1014bp locus in the CDS of dNulp1, and dNulp13# had 1bp insertion at the 1011bp locus in the CDS of dNulp1 (Fig. 3A). All these indel mutations resulted in a premature stop codon and produced an abbreviated poly-peptide chain (Fig. 3B).

Fig. (3).

CRISPR/Cas9 system mediated dNulp1 knockout. (A) Partial structure and sequence of the dNulp1 gene shows the CRISPR/Cas9 target site, which is located in exon3 of the dNulp1 gene (yellow boxes region indicate the exons, blue region is the target locus). F and R are the upstream and downstream primers of target locus respectively. Partial sequencing blast results between wild-type and mutant lines are shown in the bottom of Fig. 2A, Lines 1# and 4# had 2bp deletions at 1007-1008bp in the CDS of dNulp1, Line 2# had 1bp knock in at 1014bp in the CDS of dNulp1, and line 3# had 1bp knock in at 1011bp in the CDS of dNulp1. (B) Schematic showing the domain structure of dNulp1 in WT and four mutant lines. (C) Western blot analysis of fly Nulp1 in lysates from wild-type (WT), homozygous dNulp11#, and homozygous dNulp12# larvae. As expected the dNulp11# and dNulp12# homozygous larvae are devoid of full length dNulp1 protein. (Color figure available online).

To check how expression of dNulp1 was affected by the deletions in the on-target locus, we extracted total protein from dNulp11# and dNulp12# homozygous larvae. Western analysis using a fly nulp1 polyclonal antibody [16] showed that the full length dNulp1 protein was not expressed in dNulp11# and dNulp12# homozygotes (Fig. 3C).

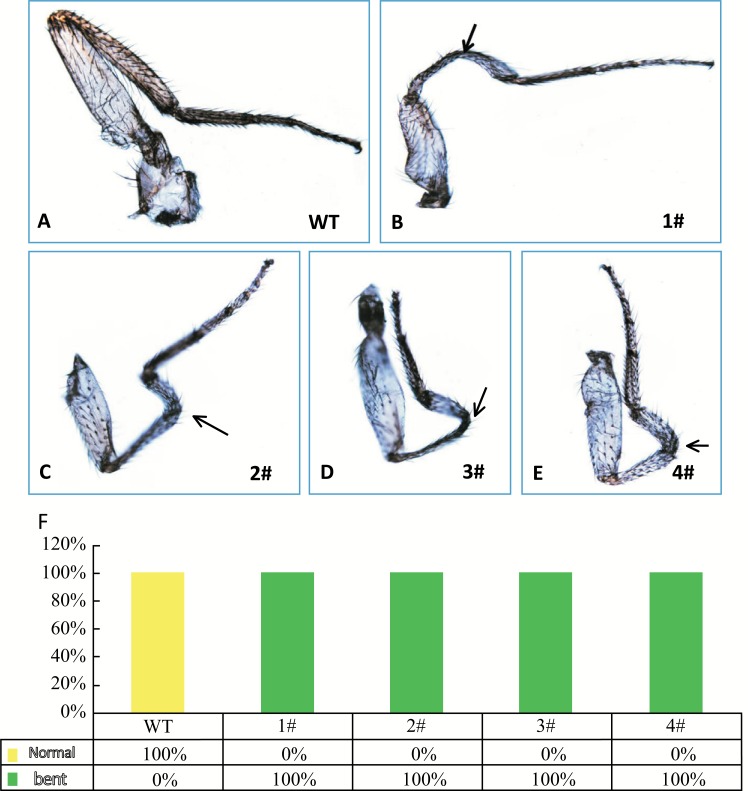

3.4. dNulp1 is Essential for Survival and Development of Flies

The four dNulp1 mutations all caused the same developmental defects compared with WT (Fig. 4A-E) and partial lethality throughout pupal stages, namely, 100% of WT flies survived to the adult stage, while 80% dNulp1-/- homozygous mutants died by late pupal stages, just before eclosion. The 20% of dNulp1-/- escapers that reached adulthood died by two weeks of adult age. dNulp11# (dNulp1-/-) was chosen for further analysis. Rare homozygous escapers from dNulp11# mutant could reach adulthood at a low frequency (N=10/50), and exhibited distinct femur defects (Fig. 4B-E). The percentage of escapers and their morphological defects were overall similar among the four dNulp1 mutant lines (Fig. 4F).

Fig. (4).

dNulp1 is essential for the development of fly femurs. (A) Normal femurs in WT flies. (B-E) Bent femurs in dNulp1-/- escapers (dNulp11#-4#) are marked with arrow. (F) Percentage of normal or bent femurs in WT and dNulp1-/-, all dNulp1-/- flies show bent femurs. N=20.

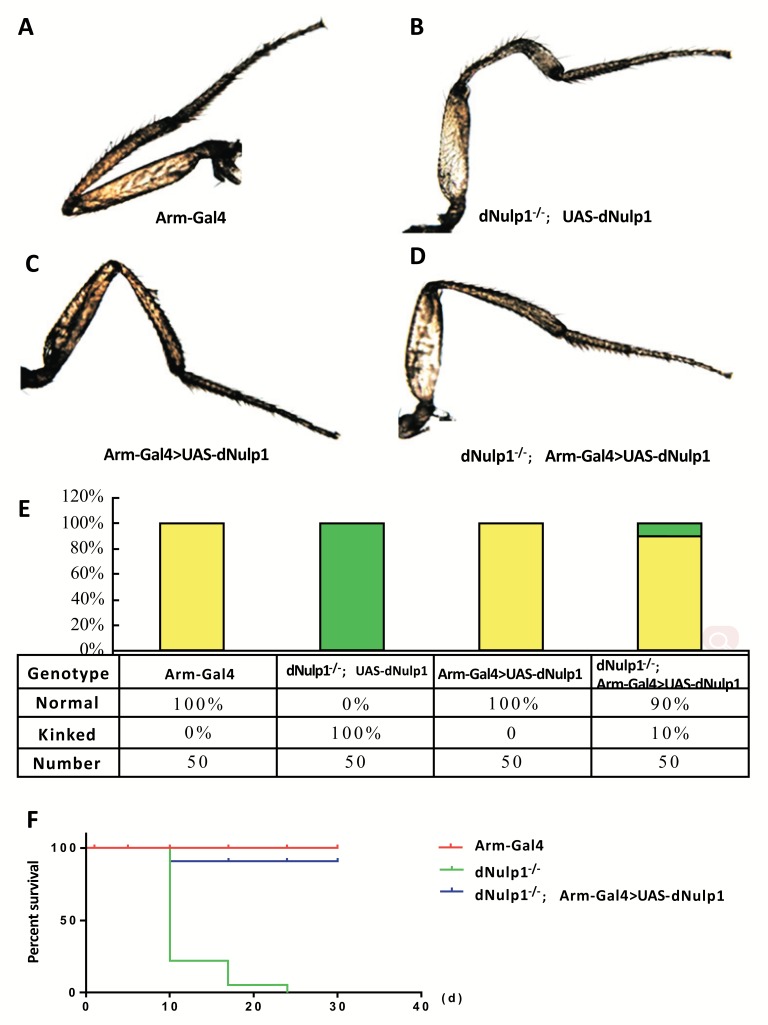

To prove that the deletion in dNulp1 was responsible for the lethal phenotype of dNulp11# mutants, we determined whether the lethality of dNulp11# could be rescued by over-expressing UAS-dNulp1-PA using the ubiquitous Arm-Gal4 driver. We crossed UAS-dNulp1-PA; dNulp11#/TM6B-ubi-GFP flies with Arm-Gal4; dNulp11#/TM6B-ubi-GFP flies and progeny lacking the TM6B-ubi-GFP marker were cultured at 25°C. Approximately 90% of UAS-dNulp1-PA/Arm-Gal4; dNulp11# pupae eclosed as normal adults and showed no femur defects (Fig. 5A-F). This result indicates that dNulp1-PA is able to rescue the lethal phenotype and bent femurs of dNulp11# mutants.

Fig. (5).

The dNulp1-PA form is sufficient to rescue the bent femurs in dNulp1-/- mutants. (A-D) Femurs of flies of different genotypes, (A) Arm-Gal4, control, shows normal femur. (B) dNulp1-/-; UAS-dNulp1, dNulp1 homozygous mutant, shows bent femur. (C) Arm-Gal4>UAS-dNulp1, dNulp1 over-expression line, does not exhibit any femur defects. (D) Only 10% of flies had bent femurs when dNulp1 was over-expressed in the dNulp1-/- homozygous mutant background (dNulp1-/-; Arm-Gal4>UAS-dNulp1). (E) Percentage of normal or bent femurs in the different genotypes. 90% of flies exhibited normal femurs with dNulp1 over-expression. (N=50). (F) Percent survival of wt (red), dNulp1-/- homozygous mutant (green), and dNulp1 rescue (blue). Over-expression of dNulp1 rescued the lethality of dNulp1-/- to 90% adult survivorship at 30 days. X-axis shows the percent survival, Y-axis shows the days after birth. (Color figure available online).

3.5. dNulp1 Acts as a Cofactor in the Wg Signaling

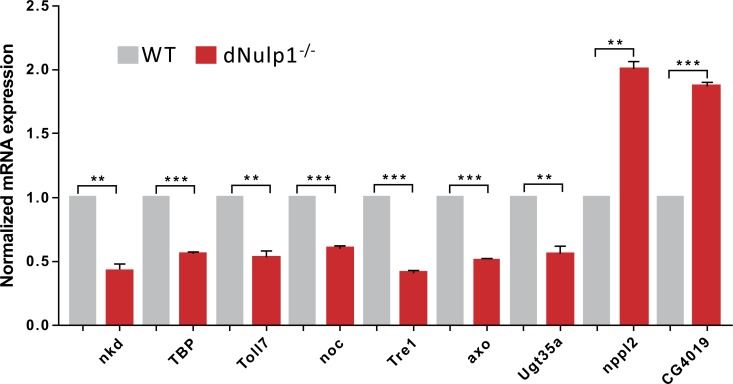

To study the specific role of dNulp1 in Wnt signaling in Drosophila, we used quantitative PCR to examine whole body mRNA expression levels in dNulp1 knockout and WT flies. Other researchers identified some key Wnt/Wg target genes [19], including naked cuticle (nkd), TBP, Toll7, noc, Tre1, axo and Ugt35a, that were significantly down-regulated, and nplp2 and CG4019 that were significantly up-regulated in dNulp11# KO flies compared to WT (Fig. 6). These results suggest that dNulp1 modulates the Wnt signaling pathway.

Fig. (6).

Gene expression analysis of Wg/Wnt target genes in dNulp1-/- mutant flies. Expression of candidate wnt target genes was quantified using qRT-PCR, in WT and dNulp1 knock out flies. In all cases mRNA levels were normalized relative to rp49 levels and mutant expression data are displayed normalized to wt levels. (***p<0.001, **p<0.01, paired T test).

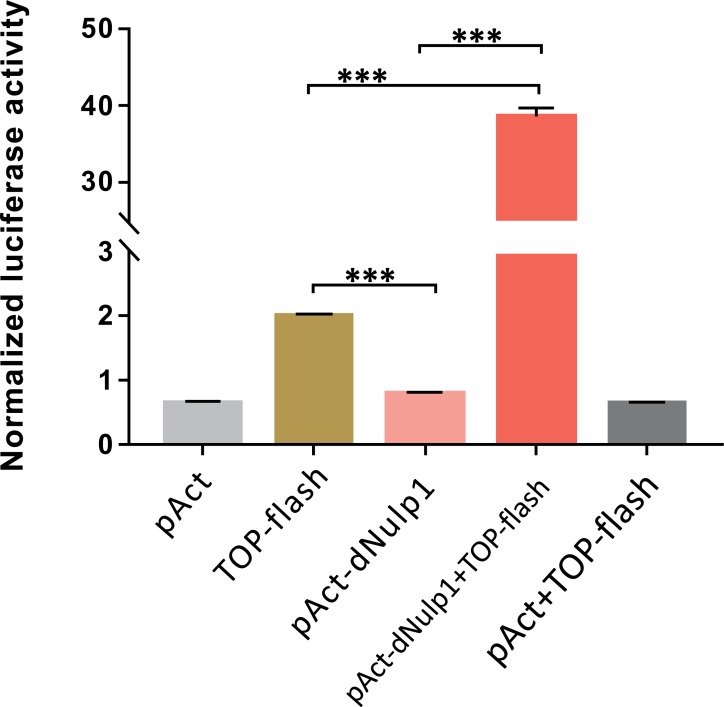

To verify this, we used the Top-Flash luciferase reporter assay in S2 cell; this reporter gives a robust response to Wg signaling [14, 24, 25]. Overexpression of dNulp1 stimulated the Top-Flash reporter activity by 38.6 fold (Fig. 7). Taken together, these results indicate that dNulp1 can activate Wnt/Wg pathway.

Fig. (7).

dNulp1 increases the TOP-Flash activity. The basal activity (negative controls) of WNT/β-catenin signaling is seen in S2 cells where only pAct-back, pAct-dNulp1, TOP-flash, orpAct+TOP-flash were transfected individually. Co-transfection of pAct-dNulp1 together with TOP-flash (red), caused a significant increase in WNT/β-catenin signaling (~38 fold). (***p<0.001, paired T test). (Color figure available online).

4. DISCUSSION

The dNulp1 protein contains a domain of unknown function DUF654 in the C-terminus and a bHLH domain in N-terminal, making it a new member of the bHLH family. The dNulp1 protein shares high homology with other nulp1 proteins, especially in these two domains, indicating that the function of Nulp1 is evolutionarily conserved between flies and humans. It is well known that bHLH proteins participate in cell fate-determination and differentiation of most organs [4]. Apart from these observations, the role of Nulp1 in biological processes remains unknown.

We have now identified a genetic link between dNulp1 and Wnt/Wg signaling through a screen that looked for rescue of the notch wing phenotype caused by the over-expression of sgg (GSK3β), a negative regulatory factor of the Wnt signaling pathway [20, 26]. The notch phenotype induced by sgg overexpression was rescued by co-overexpression of dNulp1 and loss of dNulp1 had similar effects on the mRNA levels of known Wnt/Wg signaling target genes. All 4 of our CRISPR/Cas9 generated dNulp1 knockout lines exhibited the same phenotypic defects, including partial lethality through pupal stages and bent femurs in adult escapers. Moreover, the lethality and bent femurs could be rescued by the over-expression of dNulp1. The fly appendage phenotype caused by dNulp1 knockout is similar to what is observed in flies with hypoactive Wnt/Wg signaling [14, 15], suggesting that dNulp1 is involved in Wg signaling. In this study, the sites of indel mutations mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 were far from the initiation codon and produced abbreviated polypeptides that included the entire bHLH domain and part of the DUF654 domain, suggesting that a more severe phenotype maybe observed when the entire protein is deleted.

Our results show that dNulp1 is essential for femur development and survival in Drosophila, which is similar to the major manifestation of congenital bent-bone dysplasia in human Stuve-Weidemann syndrome. A major phenotype in STWS patients is the bowing of the long bones (particularly the tibia and the femur) with frequent death in infancy [16]. While defects in the LIFR gene is one of the clinical molecular diagnostic markers, not all STWS patients have LIFR mutations, suggesting that other causative genes for STWS remain to be identified [27]. It is possible that Nulp1 is involved in this syndrome and if so it could be used as a clinical molecular diagnostic marker in STWS.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we provide evidence that the bHLH protein dNulp1 acts as a cofactor in Wnt/Wingless signaling and is essential for survival and development of flies, which is similar to the major

manifestation of congenital bent-bone dysplasia in human Stuve-Weidemann syndrome. Furthermore, dNulp1 plays a role downstream of sgg in the Wnt signaling pathway to affect the expression of specific target genes in D. melanogaster. Involvement of dNulp1 in Wg signaling raises a possibility that mammalian Nulp1 and other bHLH proteins may also play a role in Wnt signaling. Further work on identifying interactions between Nulp1 and β-catenin/TCF will be required to fully understand the specific role of dNulp1 in Wg signaling.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.: 81470449, 81470377, 81670290, 31572349, 81370451, 31472060, 81400304, 81270156, 81370230, 81570279, 81670288, 81370341, 81700338), the Cooperative Innovation Center of Engineering and New Products for Developmental Biology of Hunan Province (No. 2013-448-6), China National Ministry of Science and Technology key national research and development plan: SQ2017ZY050117, Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation project:1714060000079, and Guangzhou Science and Technology Plans major projects of Production-study-research cooperative innovation: 201508020107.

Abbreviations

- bHLH

The basic Helix-Loop-Helix

- UAS

Upstream Activating Sequence

- GFP

Green Fluorescent Protein

- TLV

Truncated Longitudinal Veins

- HRMA

High Resolution Melting Assay

- CDS

Coding Sequence

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available on the publisher's website along with the published article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Rights

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- 1.Wood W.M., Etemad S., Yamamoto M., Goldhamer D.J. MyoD-expressing progenitors are essential for skeletal myogenesis and satellite cell development. Dev. Biol. 2013;384(1):114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu G., Zhang J., Wang L., et al. Sex- and age-dependent expression of Pax7, Myf 5, MyoG, and Myostatin in yak skeletal muscles. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016;15(2) doi: 10.4238/gmr.15028020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thattaliyath B.D., Firulli B.A., Firulli A.B. The basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor HAND2 directly regulates transcription of the atrial naturetic peptide gene. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34(10):1335–1344. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atchley W.R., Fitch W.M. A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94(10):5172–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson S.R. Turner Dl, Weintraub H, Parkhurst SM. Specificity for the hairy/enhancer of split basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins maps outside the bHLH domain and suggests two separable modes of transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15(12):6923–6931. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjalt T. Basic helix-loop-helix proteins expressed during early embryonic organogenesis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2004;236:251–280. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)36006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Z., Wang Y., Yu W., et al. hnulp1, a basic helix-loop-helix protein with a novel transcriptional repressive domain, inhibits transcriptional activity of serum response factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;343(3):973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X., Golden K., Bodmer R. Heart development in Drosophila requires the segment polarity gene wingless. Dev. Biol. 1995;169(2):619–628. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takaesu N.T., Johnson A.N., Sultani O.H., Newfeld S.J. Combinatorial signaling by an unconventional Wg pathway and the Dpp pathway requires Nejire (CBP/p300) to regulate dpp expression in posterior tracheal branches. Dev. Biol. 2002;247(2):225–236. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X. Wg signaling in Drosophila heart development as a pioneering model. J. Genet. Genomics. 2010;37(9):593–603. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang M., Yuan W., Fan X., et al. Pygopus maintains heart function in aging Drosophila independently of canonical Wnt signaling. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(5):472–480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nusse R., Varmus H. Three decades of Wnts: a personal perspective on how a scientific field developed. EMBO J. 2012;31(12):2670–2684. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salasova A., Yokota C., Potesil D., Zdrahal Z., Bryja V., Arenas E. A proteomic analysis of LRRK2 binding partners reveals interactions with multiple signaling components of the WNT/PCP pathway. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim G.W., Won J.H., Lee O.K., et al. Sol narae (Sona) is a Drosophila ADAMTS involved in Wg signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31863. doi: 10.1038/srep31863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramps T., Peter O., Brunner E., et al. Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF complex. Cell. 2002;109(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koul R., Al-Kindy A., Mani R., Sankhla D., Al-Futaisi A. One in three: congenital bent bone disease and intermittent hyperthermia in three siblings with stuve-wiedemann syndrome. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2013;13(2):301–305. doi: 10.12816/0003238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxford A.E., Jorcyk C.L., Oxford J.T. Neuropathies of Stüve-Wiedemann Syndrome due to mutations in leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) gene. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016;1(7):37–44. doi: 10.29245/2572.942x/2016/7.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsson M., Durbeej M., Ekblom P., Hjalt T. Nulp1, a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein expressed broadly during early embryonic organogenesis and prominently in developing dorsal root ganglia. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;308(3):361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franz A., Shlyueva D., Brunner E., Stark A., Basler K. Probing the canonicity of the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(4):e1006700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadopoulou D., Bianchi M.W., Bourouis M. Functional studies of shaggy/glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation sites in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24(11):4909–4919. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4909-4919.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomlinson A., Strapps W.R., Heemskerk J. Linking Frizzled and Wnt signaling in Drosophila development. Development. 1997;124(22):4515–4521. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourouis M. Targeted increase in shaggy activity levels blocks wingless signaling. Genesis. 2002;34(1-2):99–102. doi: 10.1002/gene.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Housden BE, Perrimon N. 2016.

- 24.Kessler R., Hausmann G., Basler K. The PHD domain is required to link Drosophila Pygopus to Legless/beta-catenin and not to histone H3. Mech. Dev. 2009;126(8-9):752–759. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu T., Phiwpan K., Guo J., et al. MicroRNA-142-3p Negatively Regulates Canonical Wnt Signaling Pathway. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun C., Luan S., Zhang G., Wang N., Shao H., Luan C. CEBPA-mediated upregulation of the lncRNA PLIN2 promotes the development of chronic myelogenous leukemia via the GSK3 and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017;7(5):1054–1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dagoneau N., Scheffer D., Huber C., et al. Null Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor (LIFR) Mutations in Stuve-Wiedemann/Schwartz-Jampel Type 2 Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74(2):298–305. doi: 10.1086/381715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material is available on the publisher's website along with the published article.