Alzheimer’s disease (AD) currently affects 5.3 million Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2010) and will inflict an estimated 14 million by 2050 (Hebert, Scherr, Bienias, Bennett, & Evans, 2003). Older adults with AD experience functional decline that contributes significantly to poor healthcare outcomes and incurs enormous expenditure (Yu, Kolanowski, Strumpf, & Eslinger, 2006). Aerobic training is a potential intervention that could mitigate functional decline and its negative impact by improving cardiovascular fitness.

Cardiovascular fitness is defined as the ability of the heart to deliver oxygen to the body and is estimated as maximal or peak oxygen consumption (VO2max or peak) (American College of Sports Medicine, 2005). Important for independence and mortality (Sui et al., 2007; Vogel et al., 2009), VO2peak needs to be at least 15–18 ml/kg/min for older adults to perform daily activities (Hawkins & Wiswell, 2003). However, older adults often do not meet this minimum and experience accelerated decline in cardiovascular fitness at 15–22% per decade (Fleg et al., 2005; Hollenberg, Yang, Haight, & Tager, 2006). Individuals with decreased cardiovascular fitness tend to avoid exercise which further reduces cardiovascular fitness (Vogel et al., 2009). This downward spiral is inadvertently catalyzed by AD because older adults with AD already show functional decline, lack awareness and motivation for exercise, and manifest challenging AD symptoms. Excess disability also becomes common when caregivers take over tasks, become overly protective, and do too much for older adults with AD (Rogers et al., 1999).

Although aerobic training has shown numerous health benefits in older adults (Vogel et al., 2009), findings are inconsistent in those with AD and other dementias (Forbes et al., 2008; Heyn, Abreu, & Ottenbacher, 2004). One prevailing issue is the wide variation of exercise programs in terms of exercise mode (aerobic or non-aerobic), intensity (very low or high), frequency (1–6 times/week), session duration [10–60 minutes (min)], program duration (2–12 months), and delivery (subjectively reported or supervised). Few studies included aerobic training at the recommended moderate intensity, 150-min weekly dose for older adults (American College of Sports Medicine, 2005). For studies that did meet this recommendation, it is unclear whether the prescribed dose was successfully delivered and resulted in gain in cardiovascular fitness. Hence, there exists a critical need to develop aerobic training programs that can be safely and successfully delivered to older adults with AD. The purposes of this paper are to describe the change in cardiovascular fitness from 2 months of aerobic training and the feasibility of aerobic training in four men with moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

Design

A one-group, pre-post test design was used to measure cardiovascular fitness at baseline and post-training. Exit interviews were conducted with spouses and participants separately using open ended questions to identify facilitators and barriers for exercise participation.

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited through local AD support groups and newspaper advertisements from June 2007 to April 2008. The inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 60 years old; community-dwelling; AD diagnosis; English speaking; and resting heart rate (HR) < 100 beats per minute. The exclusion criteria included: psychiatric illness, alcohol, or chemical dependency within the preceding 5 years; unstable medical conditions within the past 6 months (e.g., heart attack, stroke); HR-altering medications; physician’s advice against aerobic training; symptoms unevaluated by a physician (e.g., chest pain, shortness of breath); and electrocardiogram (ECG) readings indicative of cardiac ischemia during baseline exercise testing. This study was approved by the university’s IRB. Because all participants lacked decision-making capacity, surrogate consents were obtained from spouses and assents from participants. Of the 20 respondents, 15 did not have AD and five were eligible, but one dropped out due to surgery. Participants received $75 in compensation, a Certificate of Completion, and some transportation assistance.

Exercise testing was conducted at the university’s General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) exercise testing room where an ECG machine and a computer-controlled Lode Corival (906900) cycle ergometer (Lode BV, Groningen, Netherlands) was housed. Aerobic training took place at the Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene and Exercise Science where two Precor™ recumbent stationary cycles (Precor, Woodinville, WA) were available for exercise training.

Procedures

A trained research assistant (RA) conducted the initial phone interviews. The principal investigator (FY) corroborated health data and obtained consents at the GCRC, and the RA administered the Mini-Mental State Examination – MMSE (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) for assessing baseline cognition. After a GCRC nurse measured participant’s height and weight, an exercise physiologist applied the ECG electrodes and started exercise testing on the Lode cycle ergometer. A graded protocol was started at 20–50 Watts (W) for 3 min and increased by 10–20W every 2 min until symptom limited peak (American College of Sports Medicine, 2005). The exercise physiologist took blood pressure (BP) after 10-min resting, during the last 15 sec of each power stage, cool-down, and recovery, while FY instructed the participant. A cardiologist (ASL) monitored ECG readings and determined if cardiac ischemia developed.

Exercise training involved 2-month, moderate intensity cycling on Precor™ cycles supervised by a trained trainer, 3 times/week, and was prescribed based on HR reserve (HRR = peak HR during exercise testing – resting HR; see Table 1). In each session, participants wore a Polar™ F7 HR monitor (Polar Electro Finland Oy, Kempele, Finland) and did a 5–10-min cardiovascular warm-up and cool-down before and after cycling at target doses. The trainer monitored the participant’s HR, signs and symptoms (e.g., skin color, sweat, and breathing), and talking ability, adjusted cycling speed, resistance, and duration accordingly, and served water to participants. FY randomly checked 10% of sessions to ensure treatment fidelity. The RA conducted exit interviews. Exercise testing was repeated within one week of training completion.

Table 1.

Prescribed Aerobic Exercise Training Progression

| Week | Target HR Range (resting HR + % of HRR) |

Duration at Target HR (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 – 50 | 10–15 |

| 2 | 40 – 50 | 15–20 |

| 3 | 50 – 60 | 15–20 |

| 4 | 50 – 60 | 20–25 |

| 5 | 60 – 65 | 20–25 |

| 6 | 65 – 70 | 20–25 |

| 7 | 65 – 70 | 25–30 |

| 8 | 65 – 70 | 25–30 |

Measures

Cardiovascular fitness was defined as absolute and relative VO2peak estimated from peak power achieved during exercise testing. Estimate absolute VO2peak (mL·min−1) = relative VO2peak×weight (kg) (Wasserman, Hansen, Sue, Stringer, & Whipp, 2005). Estimate relative VO2peak (mL·kg·min−1) = 1.8 (power)/weight (kg) + 7.0 (American College of Sports Medicine, 2005).

Training feasibility was measured quantitatively and with open ended questions. Quantitatively, training feasibility was defined as the number of completed training sessions, number and percent of sessions that met training goals, percent of HRR actually achieved, and cycling duration with and without warm-up and cool-down. At exit interviews, participants and spouses were asked to identify exercise facilitators and barriers: “You/your spouse have participated in a biking program during the past 2 months. What we would like to focus on now is what motivates you/your spouse to come and bike. Think for a moment on that. Can you give an example of what motivates you/your spouse to come to bike? We would also like to focus on what it is that stops you/your spouse from coming. Think for a moment on that. Can you give an example of what stops you/your spouse from coming to bike?”

Data Analysis

All data were entered into a Microsoft Excel database and double checked for accuracy. Estimate absolute and relative VO2peak were calculated in Excel. SPSS 17.0 was used to analyze actual training doses and generate graphs. Exit interview data were transcribed verbatim.

Results

Case 1

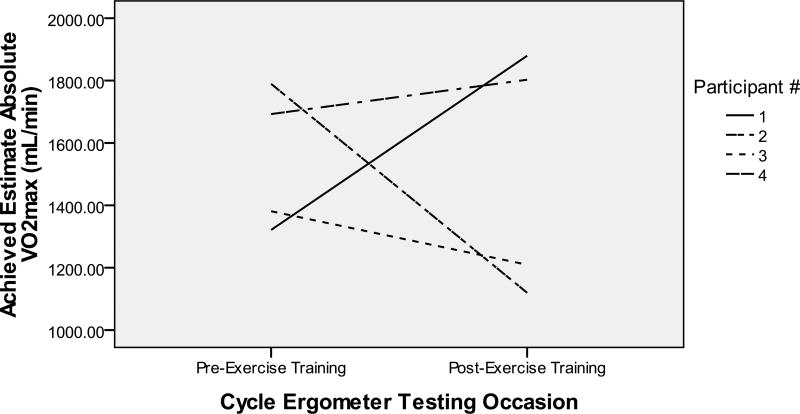

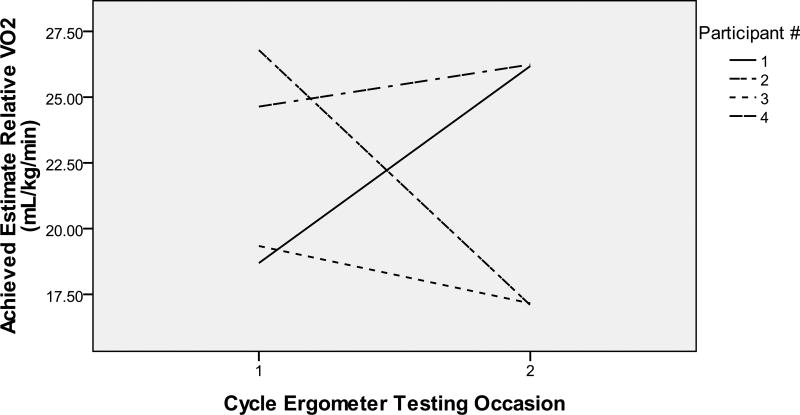

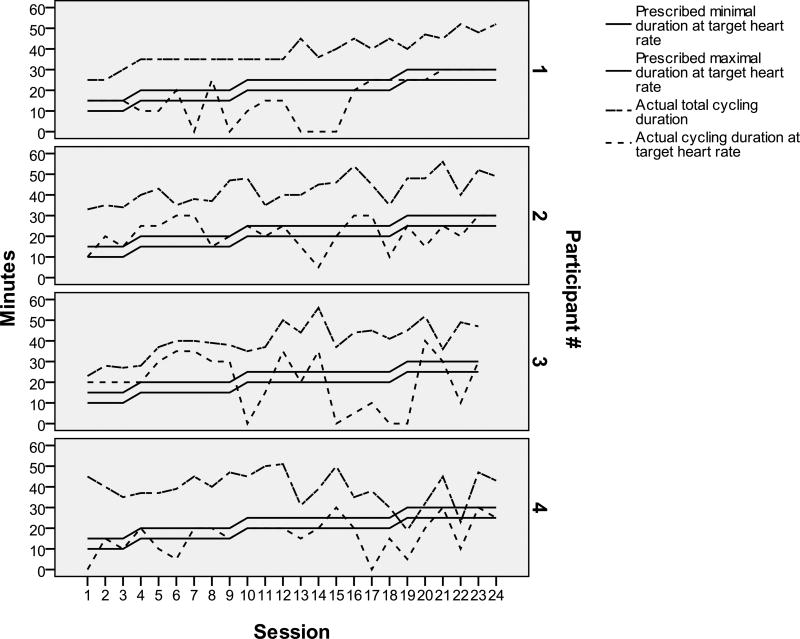

Participant 1 was a 72 year old Caucasian man (20-year education, baseline MMSE 12) who lived at home with his spouse. He showed an increase from 1321.1 to 1879.6 mL/min in estimate absolute VO2peak from baseline to post-training (see Figure 1) and from 18.7 to 26.2 mL/kg/min in estimate relative VO2peak (see Figure 2). He completed 24 training sessions: 54.2% met training goals (see Table 2). He started at 39% of HRR, increased his HR over time, and peaked at 61% of HRR by week 7 (see Table 3). Because his HR rose slowly, he had a longer cardiovascular warm-up and cool-down (see Figure 3). Exercise facilitators included: 1) “I thought it would be good for him because particularly during the winter months he is relatively inactive” (spouse); and 2) “I appreciate the effort and goals of the study and I think it is exciting to be a part of it” (spouse); 3) “Because we said we were going to. My wife told me about it and I said okay. So we came in and it is now” (participant); and 4) “I have not really thought about exercising because I can not think of things” (participant). No barriers were identified.

Figure 1.

Estimate Aerobic Capacity from Pre- to Post-Training

Figure 2.

Estimate Relative Aerobic Capacity from Pre- to Post-Training

Table 2.

Feasibility of the Exercise Training Prescriptions

| Participant | Baseline MMSE |

# of Training Session Completed |

# (%) of Sessions with Unmet Training Goal |

# (%) of Sessions with Met Training Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 24 | 11 (45.8%) | 13 (54.2%) |

| 2 | 7 | 24 | 9 (37.5%) | 15 (62.5%) |

| 3 | 2 | 23 | 10 (43.5%) | 13 (56.5%) |

| 4 | 10 | 24 | 15 (62.5%) | 9 (37.5%) |

| Total | 95 | 45 (47.1%) | 50 (52.9%) |

Note: MMSE – Mini-Mental State Examination. An exercise session was categorized as meeting the training goal if both the target training HR and the cycling duration at the target HR were met.

Table 3.

Percentage of HRR (% HRR) Participants Actually Achieved During Training

| Week | Prescribed % HRR |

Actual % HRR Achieved | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Participant 2 | Participant 3 | Participant 4 | ||

| 1 | 40 – 50 | 39 | 41 | 67 | 33 |

| 2 | 40 – 50 | 39 | 44 | 64 | 39 |

| 3 | 50 – 60 | 45 | 55 | 69 | 44 |

| 4 | 50 – 60 | 45 | 53 | 50 | 48 |

| 5 | 60 – 65 | 49 | 56 | 61 | 63 |

| 6 | 65 – 70 | 58 | 64 | 47 | 54 |

| 7 | 65 – 70 | 61 | 61 | 69 | 72 |

| 8 | 65 – 70 | 61 | 65 | 72 | 71 |

Note: Participant 1: Resting HR = 57 bpm; HRR = 109 bpm; Participant 2: Resting HR = 58 bpm; HRR = 95 bpm; Participant 3: Resting HR = 68 bpm; HRR = 36 bpm; Participant 4: Resting HR = 58 bpm; HRR R = 90bpm.

Figure 3.

Actual Cycling Duration in Comparison to Prescribed Cycling Duration

Case 2

Participant 2 was a 61 year old Asian man (19-year education, baseline MMSE 7, English as the 2nd language) who lived at home with his spouse/daughter. At both exercise testing sessions, he could not understand and follow instructions. He showed a decrease in cardiovascular fitness from 1789.5 to 1119.5 mL/min in estimate absolute VO2peak (see Figure 1) and from 19.3 to 17.2 mL/kg/min in estimate relative VO2peak (see Figure 2). He completed 24 training sessions: 62.3% met training goals (see Table 2). He exercised at his prescribed HRR except for weeks 5–7 and the prescribed durations except for weeks 4–6 when he experienced visual hallucinations, talked to self, had side effects from a new medication, and “has gotten the idea that the bike is going to break or something and has not been looking forward to it as much” (spouse). Despite medication side effects and the thought of broken bike, he cycled with increasing durations over time (see Figure 3). It became evident per spouse that his ability to understand English had declined. Toward the end of the study, the spouse actually spoke to him in his native language. Exercise facilitators were: 1) “We wanted to help you get the program going. He loves to exercise so I thought he would enjoy it. He seemed to enjoy it most of the time” (spouse); and 2) “I am an athlete and I want to keep my body as good as I can… it is fun and I like to be around people who are also just like me who like to talk and think and it’s fun” (participant). Barriers included: “Just working out the transportation and the time commitment” (spouse).

Case 3

Participant 3 was an 82 year old Caucasian man (17-year education, baseline MMSE 2, English as the 2nd language) who lived at home with spouse. During baseline exercise testing, his legs fatigued shortly after the testing started with abnormal HR responses (decreasing with increasing power). During post-training exercise testing, his HR responded normally: increasing as power increased. He showed a decrease from 1381.1 to 1209.5 mL/min in estimate absolute VO2peak (see Figure 1) and from 26.8 to 17.1 mL/kg/min in estimate relative VO2peak (see Figure 2). He completed 23 training sessions: 56.5% met training goals (see Table 2). His HR was higher for weeks 1–3 and lower for week 6 than prescribed HRR (see Table 3). He cycled at the prescribed durations at prescribed HRR in weeks 1–4, but only occasionally afterwards (see Figure 3). Exercise facilitators included: 1) “He always enjoyed exercising. He used to walk a lot” (spouse); 2) “I think he likes everybody in the group. He is a shy person. At the beginning he was a little shy, but then he became very bold. He was very open, don’t you think? He was always joking around with her or you. He really enjoyed it and he benefited a lot from it” (spouse); and 3) “Anything that is good for him” (spouse). Barriers were “Time frame is nothing to him anymore. He dilly dallies. The biggest problem was getting his clothes on and get him ready for exercise sessions” (spouse).

Case 4

Participant 4 was a 68 year old Caucasian man (18-year education, baseline MMSE 10) who lived at home with his spouse. He showed an increase from 1692.66 to 1802.82 mL/min in estimate absolute VO2peak (see Figure 1) and from 24.6 to 26.2 mL/kg/min in estimate relative VO2peak (see Figure 2). He completed 24 sessions: 37.5% met training goals (see Table 2). He reached 33–48% and 71–72% of HRR for weeks 1–6 and 7–8 (See Table 3). Durations at prescribed HRR were met for week 1. Total cycling durations increased in weeks 1–4 and varied in weeks 5–8 (see Figure 3). He had several anger outbursts during training. Exercise facilitators included: 1) “I think it is helpful for him, partly because he got a lot of positive affirmation so he felt good about that” (spouse); 2) “He was more aware from the beginning of his diagnosis. We wanted to be available to participate in any studies that could help somebody else” (spouse); and 3) “Cause it works. It makes you feel stronger or cleaner or whatever” (participant). Barriers were: “It was very time consuming. It took a hunk out of the week” (spouse).

Discussion

In these four case studies of older adults with moderate-to-severe AD, we found that cardiovascular fitness improved in two participants who had higher MMSE scores (MMSE 10 & 12), but decreased for two participants with lower MMSE scores (MMSE 2 & 7). The lack of improvement in those with lower MMSE scores suggests that the aerobic training doses were inadequate for a training effect to occur. In our study, aerobic training was prescribed based on baseline laboratory-based, graded exercise testing which is a very challenging way to measure cardiovascular fitness in individuals with AD for research purposes. It requires special exercise equipment, ECG monitor, sphygmomanometer, and the presence of several professional staff (i.e., licensed cardiologist, exercise physiologist, and nurse). Furthermore, older adults with AD might not be able to understand and follow testing instructions or be too physically de-conditioned to maintain a required cycling speed with increasing resistance. Although we had the mechanical and professional resources, participant 2 did not seem to understand testing instructions and participant 3 reported leg fatigue shortly after baseline testing began. For those two participants, it is likely that a lower than actual cardiovascular fitness was estimated, resulting in low intensity training prescriptions. They were then able to complete a higher percentage of sessions at low intensity that met targets than participants 1 and 4 whose cardiovascular fitness was more accurately measured. Since individuals with lower VO2peak are more likely to benefit from aerobic training (Vaitkevicius et al., 2002), aerobic training offers great promise for older men with AD. Hence, future studies need to further examine the utility of graded exercise testing and alternative measures for assessing cardiovascular fitness to assist aerobic training prescriptions in this population.

Despite the available norms for cardiovascular fitness in older adults, little is known about how cardiovascular fitness changes naturally or in response to aerobic training in those with AD. The average estimate relative VO2peak of our participants at baseline was lower than men with mild cognitive impairment (22.4 ± 4 vs. 25.2 ± 4.2) (Baker et al., 2010). It is also possible that although two participants declined in cardiovascular fitness, the extent of their decline had been reduced by our 2-month training program in comparison to their natural course of decline. Despite the drop in cardiovascular fitness, participants 2 and 3 tolerated duration progression like participants 1 and 4. Together, those findings suggest that our exercise program might be used as the adaptive period for progressing older adults with AD to longer duration training programs (e.g., 6–12 months) at moderate intensity and a control group should be included in future studies.

The suggestion of using our exercise program as the adaptive period was also based on our results that participants only reached 38–57% of prescribed doses with wide variations in training progression. Hence, ensuring the delivery of adequate exercise doses should be the cornerstone for future outcome studies in AD. If a sufficient aerobic training dose was not delivered, then it would be unreasonable to expect treatment effects. Further, the change in cardiovascular fitness provides important information on treatment delivery and might play a major dose-response role in outcome differences. Recent studies reported improvements in cognition and cardiovascular fitness in those with mild cognitive impairment (Baker et al., 2010; Lautenschlager et al., 2008), but outcome studies of aerobic training in AD are limited.

A variety of strategies are needed to engage older adults with AD in aerobic training. The trainer must know and establish rapport with participants in order to adequately assess exercise responses and gauge exercise progression for participants, e.g., symptoms, sweating patterns, breathing, talking ability, HR, and perceived exertion (Yu & Bil, 2010). Repeated coaching and individualized training are essential for a participant’s enjoyment, adherence, and compliance to training. AD is a progressing, deteriorating condition, which causes different symptoms across people, whereas symptoms change for the same person over time. Different behavioral symptoms, which are expressions of unmet needs by people with AD (Algase et al., 1996), might appear and be worse at one session than another. Hence, strategies working in the early weeks of training might not work in latter weeks. In our study, the trainer did not challenge participants’ visual hallucination or anger, re-assured safety when the participant thought the cycle was broken, and helped his spouse to resolve reasons for his anger. The barriers and facilitators reported by participants and spouses suggest that adequate resources such as transportation assistance will be necessary for the recruitment and retention of older adults with AD into exercise trials. Although the spouses did not mind driving their husbands, it could be a burden for spouses if exercise programs were 6 or 12 months in duration. A language barrier likely exists for individuals whose native language is not English as we observed with our two cases. The spouses all enjoyed the respite periods when participants were with research staff by exercising themselves, reading books, going shopping, or relaxing. Individuals who used to be physically active were more likely to participate in and adhere to aerobic training. Families were particularly appreciative of the caring attitudes and competence of trainers since they lacked the resources or influence that trainers possessed to encourage exercise in their family members with AD. Participants who found the training enjoyable and fun tended to adhere to training better and made an effort to cooperate. In comparison, monetary compensation did not appear to be important.

Conclusion

Older men with moderate-to-severe AD can engage in aerobic training. Two months of aerobic training could be too short for improving cardiovascular fitness particularly in those with more severe dementia. However, this time period could serve as the adaptive period for longer duration exercise at moderate intensity. Future research needs to determine the optimal way to measure change in cardiovascular fitness and prescribe aerobic training in older adults with AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a NIH K12 Career Advancement Award (RR023247-04) and an American Nurses Foundation Research Grant (# 2005102). Dr. Leon is partially supported by the H.L. Taylor Professorship in Exercise Science and Health Promotion. The authors thank the participants, their family members, and local support group staff for their support. The authors also thank Susan McPherson, PhD, geriatric neuropsychologist, for consulting in the study. This publication was made possible by support (or partial support) from grant M01 RR00400 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Contributor Information

Fang Yu, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Arthur S. Leon, University of Minnesota School of Kinesiology.

Henry L. Taylor, University of Minnesota School of Kinesiology.

Donna Bliss, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Maurice Dysken, Geriatric Research, Education, and Care Center Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Kay Savik, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Jean F. Wyman, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

References

- Algase DL, Beck C, Kolanowski A, Whall A, Berent S, Richards K, et al. Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 1996;11(6):10. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. [Retrieved July 26, 2010];What is Alzheimer's? 2010 from http://alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp.

- American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for graded exercise testing and exercise prescription. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Archives of Neurology. 2010;67(1):71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleg JL, Morrell CH, Bos AG, Brant LJ, Talbot LA, Wright JG, et al. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation. 2005;112(5):674–682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, Markle-Reid M, Wood J, Culum I. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(3):CD006489. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S, Wiswell R. Rate and mechanism of maximal oxygen consumption decline with aging: implications for exercise training. Sports Medicine. 2003;33(12):877–888. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert L, Scherr P, Bienias J, Bennett D, Evans D. Alzheimer disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Archives of Physical and Medical Rehabilitation. 2004;85(10):1694–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg M, Yang J, Haight TJ, Tager IB. Longitudinal changes in aerobic capacity: implications for concepts of aging. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2006;61(8):851–858. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, Foster JK, van Bockxmeer FM, Xiao J, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1027–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JC, Holm MB, Burgio LD, Granieri E, Hsu C, Hardin JM, et al. Improving morning care routines of nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(9):1049–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, LaMonte MJ, Laditka JN, Hardin JW, Chase N, Hooker SP, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as mortality predictors in older adults. JAMA. 2007;298(21):2507–2516. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitkevicius PV, Ebersold C, Shah MS, Gill NS, Katz RL, Narrett MJ, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise training in community-based subjects aged 80 and older: a pilot study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(12):2009–2013. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel T, Brechat PH, Lepretre PM, Kaltenbach G, Berthel M, Lonsdorfer J. Health benefits of physical activity in older patients: a review. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2009;63(2):303–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue D, Stringer W, Whipp B. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation: Including pathophysiology and clinical applications. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Bil K. Correlation between Heart Rate and Perceived Exertion during Aerobic Exercise in Older Men with Alzheimer’s Disease. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2010;12(3):375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Kolanowski A, Strumpf N, Eslinger P. Improving cognition and function through exercise intervention in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(4):358–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]