Abstract

Archaeal viruses, especially viruses that infect hyperthermophilic archaea of the phylum Crenarchaeota, constitute one of the least understood parts of the virosphere. However, owing to recent substantial research efforts by several groups, archaeal viruses are starting to gradually reveal their secrets. In the present review, we summarize the current knowledge on one of the emerging model systems for studies on crenarchaeal viruses, the Rudiviridae. We discuss the recent advances towards understanding the function and structure of the proteins encoded by the rudivirus genomes, their role in the virus life cycle, and outline the directions for further research on this model system. In addition, a revised genome annotation of SIRV2 (Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus 2) is presented. Future studies on archaeal viruses, combined with the knowledge on viruses of bacteria and eukaryotes, should lead to a better global understanding of the diversity and evolution of virus–host interactions in the viral world.

Keywords: Archaea, filamentous virus, genome replication, hyperthermophile, transcription regulation, virus egress

Introduction

Studies of viruses of hyperthermophilic archaea resulted in the description of many new, previously unsuspected, virion morphotypes [1]. However, the biology of these viruses remained largely enigmatic. In the last few years, a substantial effort was made to decipher the functions of proteins encoded by archaeal viruses and to characterize different stages of the viral infection cycles. As a result, several virus–host systems, among both the Crenarchaota [2–4] and the Euryarchaeota [5–8], are emerging as promising models to study in more detail archaeal virus–host interactions. In the present review, we summarize the available information on one of such model systems, the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Sulfolobus islandicus and its rod-shaped virus SIRV (Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus) 2, provide a revised genome annotation of SIRV2 (Supplementary Table S1 at http://www.biochemsoctrans.org/bst/041/bst0410443add.htm), which should aid future functional studies with this virus, and briefly address the comparative genomics of the rudiviruses.

The Rudiviridae, comprising linear non-enveloped ds (double-stranded) DNA viruses [9] (Figure 1), is one of the nine currently recognized families of crenarchaeal viruses [1,10]. The rudiviruses appear to share a common ancestry with another family of filamentous crenarchaeal viruses, the Lipothrixviridae. The two families are unified in the order Ligamenvirales [11]. The family Rudiviridae consists of one genus, Rudivirus, and four species: SIRV1, SIRV2, ARV1 (Acidianus rod-shaped virus 1) and SRV (Stygiolobus rod-shaped virus). All of these viruses originate from terrestrial hot acidic springs in Europe: SIRV1 and SIRV2 are from Iceland (Kverkfjöll and Hveragerdi respectively), ARV1 is from Italy (Pozzuoli), and SRV is from Portugal (San Miguel, the Azores), and respectively infect hyperthermophilic species from the genera Sulfolobus, Acidianus and Stygiolobus of the order Sulfolobales [9,12,13]. Recently, an additional rudiviral genome has been sequenced (GenBank® accession number JX944686). According to the GenBank® record, this virus, SMRV1 (Sulfolobales Mexican rudivirus 1), has been recovered from a hot spring located in Los Azufres National Park, Mexico. Of the five rudivirus isolates, SIRV1 and SIRV2 are the most closely related, with 73% identity across the complete genome sequences (Figure 2). Moreover, SIRV1 and SIRV2 infect closely related strains of S. islandicus. Most of the current knowledge on the Rudiviridae stems from studies carried out with SIRV1 and SIRV2. Given the extent of similarity between these two viruses, results obtained with one virus are likely to be directly transferable to the other.

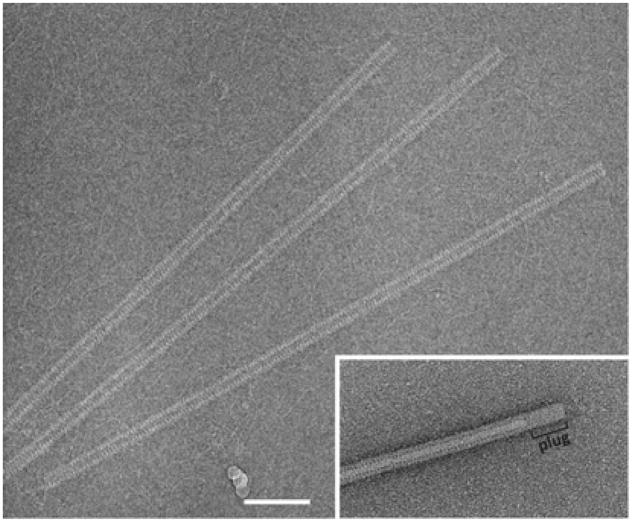

Figure 1. Cryo-electron micrograph of SIRV2 virions.

Scale bar, 100 nm. Inset, negative-contrast electron micrograph of a terminal portion of the SIRV2 virion.

Figure 2. Genomic relationships between members of the family Rudiviridae.

SIRV2 ORFs for which a function has been demonstrated or inferred in silico are shown in magenta. The names of ORFs, which encode proteins with experimentally verified functions, are underlined. Pairwise tblastx hits between rudiviral genomes are indicated by different shades of grey (the identity scale is included in the Figure). The structures of proteins of the Ligamenvirales (rudiviral or lipothrixviral) with orthologues in SIRV2 genome are shown above the SIRV2 genome map, with the source of each structure indicated in parentheses. The protein structures are coloured according to the secondary-structure elements: α-helices, blue; β-strands, magenta; coils, grey. The Figure was prepared using EasyFig [52] and UCSF Chimera [53].

Virion architecture

Virion composition and organization of rudiviruses have been investigated biochemically and by electron microscopy. The virion of SIRV2, the type member of the family, is stiff, rod-shaped and measures ~23 nm×900 nm (Figure 1). It contains no envelope and represents a tube-like superhelix formed by dsDNA and multiple copies of the viral protein P134. Negative-contrast electron micrographs suggest that, at each end, the virion tube carries plugs, ~50 nm×6 nm (Figure 1, inset). However, these plugs are absent from cryo-electron micrographs (Figure 1), and thus may represent an artefact of negative staining. Notably, as in the case of filamentous viruses infecting bacteria {circular ss (single-stranded) DNA genomes, family Inoviridae [14]} and plants (linear ssRNA genomes [15]), the virion length in rudiviruses is proportional to the length of the genomic dsDNA [13]. The overall virion organization of rudiviruses also somewhat resembles that of rod-shaped plant-infecting viruses of the family Virgaviridae. Indeed, the pitch of the virion helix is about the same (~2.3 nm) for SIRV2 and tobacco mosaic virus [10]. However, the crystal structure of the rudiviral MCP (major capsid protein), P134, revealed a unique four-helix bundle topology [16] (Figure 2), which radically differs from the fold of the tobacco mosaic virus MCP [17]. By contrast, the rudiviral MCP shares a common fold with the MCPs of the enveloped lipothrixvirus AFV (Acidianus filamentous virus) 1 [18], also a member of the order Ligamenvirales [11]. The rudiviral MCP can self-assemble to produce filamentous helical structures with diameter and pitch similar to those of the native virions [13].

At each end, the SIRV2 virion carries three terminal fibres with which it attaches to the cellular appendages of the host. The largest viral protein P1070 is a component of these fibres [19]. The fibres appear to be built up of multiple subunits ordered in a linear array [13]. Consistently, analysis of the sequence revealed the presence of a coiled-coil domain, suggesting that each fibre is a homomultimer of intertwining chains of P1070. Besides P134 and P1070, two other viral proteins, encoded by ORF488 and ORF564, were found to be present in the SIRV2 virion, albeit in a very low amount [13]. The four capsid proteins are encoded in all members of the Rudiviridae family, and the degree of sequence conservation is very high, especially for the major capsid protein (83–95% identity).

Genome, its replication and nucleic acid metabolism

The linear genome of SIRV2 consists of 35502 bp and encompasses 1628 bp-long ITRs (inverted terminal repeats). The genomes of other members of the family also contain the ITRs; however, these differ in size and sequence. The two strands of the linear dsDNA of SIRV1 are covalently linked at both ends of the genome, forming a continuous polynucleotide chain [20]. Such structural design of the genome combined with the absence of an identifiable virus-encoded DNA polymerase suggested a unique mechanism of rudiviral genome replication. SIRV1 served as an experimental model for such studies. An insight into the DNA replication mechanism was provided by the observation of single-stranded nicks at a conserved position, 11 nucleotides from the genome terminus, in approximately 5% of DNA molecules isolated from SIRV1 virions [20]. More insights into the replication process were offered by the detection of head-to-head or tail-to-tail linked replicative intermediates in SIRV1-infected cells [21]. On the basis of these results, the self-priming model of SIRV1 genome replication was proposed [22]. According to this model, the replication is initiated by the introduction of single-stranded nick at position 11 from the terminus followed by unfolding of the hairpin loop and reconstruction of the palindrome by elongating the free 3′-hydroxy end. The elongated DNA strand then folds back on itself and replication proceeds by elongation of this structure, resulting in formation of head-to-head and tail-to-tail linked replicative intermediates, which adopt cruciform topology at the borders of genome units by extrusion of the palindromic linkers formed by the ITRs. The resolution of these Holliday junction-like structures gives rise to new copies of the viral genome.

Two SIRV1/2-encoded proteins could be major players in the proposed DNA replication mechanism. The resolution of the crystal structure of P119 of SIRV1 [23,24] enabled recognition of the protein as a member of the Rep superfamily of proteins (Figure 2), which are site-specific endonucleases involved in the initiation of rolling-circle replication of diverse viruses and plasmids [25]. Although P119 and its homologues in other rudiviruses do not show significant sequence similarity to any other protein sequences in database searches performed using PSI-BLAST, HHpred search showed significant similarity (P = 91.5%) to a tyrosine transposase of the TnpA family [26] and limited similarity to other tyrosine transposases and Rep proteins. Moreover, the diagnostic sequence motifs of the Rep superfamily [25] could be identified in the multiple alignment of the rudivirus initiator proteins. The experimentally demonstrated nicking and joining activities of P119, which functions as a dimer, could be involved both in initiation of SIRV1 genome replication by nicking DNA strands close to the terminus and in the formation of a new contiguous DNA strand as a result of the joining activity [23]. Moreover, one of the nicking target sites of the recombinant P119 corresponded to the main nicking site identified in DNA isolated from SIRV1 virions, suggesting that cleavage of the sequence by P119 observed in vitro is relevant in vivo [23]. Owing to its catalytic properties, P119 could potentially be involved also in the resolution of replicative intermediates. However, the more likely candidate to perform the resolution of Holliday junctions at the boarders of two genome units is P121. This protein shows high sequence similarity to archaeal Hjrs (Holliday junction resolvases) and has been shown experimentally to possess Hjr activity; it functions as a dimer with two active centres which independently introduce two nicks in the DNA strands of the Holliday junction [27].

Sequence analysis led to the prediction that two other SIRV1/2 proteins, P158b and P207, participate in nucleic acid metabolism (Supplementary Table S1); in both cases, the putative enzymatic activities were confirmed in biochemical assays. The recombinant P158b, as predicted, was shown to represent a dUTPase, which catalyses the hydrolysis of dUTP to dUMP [28]. Among the rudiviruses, only SIRV1 and SIRV2 encode the dUTPase, but a highly conserved homologue is present in an otherwise unrelated Sulfolobus virus, STSV1 (Sulfolobus tengchongensis spindle-shaped virus 1), and in numerous archaea and bacteria. The SIRV dUTPase might play an important role in adjusting the intracellular concentration of dTTP in infected cells. Notably, the GC content of SIRV is substantially lower than that of its host (25% compared with 38% GC). Thus the pool sizes of dTTP in host cells might not be optimal for supporting rapid growth of the virus. P207, a member of the RecB nuclease superfamily [29], was indeed shown to display a single-strand-specific endonuclease activity with a cleavage mechanism similar to that of the RecB nuclease [30]. Like the dUTPase P158b, the endonuclease P207 is only present in SIRV1 and SIRV2 among the rudiviruses. Notably, among all members of the RecB family, this protein shows the strongest sequence similarity to the Cas4 protein of the CRISPR (cluster of regularly interspaced palindromic repeats)–Cas (CRISPR-associated sequences) antivirus defence system [31], suggesting the possibility that the common ancestor of SIRV1 and SIRV2 acquired this gene from a CRISPR–Cas locus. The exact role of the ssDNA endonuclease P207 during the infection cycle is unclear. One possibility is that P207 plays a role in host chromosome degradation during SIRV lytic infection.

Transcription regulation and DNA-binding proteins

The analysis of gene expression of the viruses SIRV1 and SIRV2 by Northern blot hybridization, from 30 min to 3 h after infection, revealed that there is little temporal regulation of viral gene expression [32]. Many genes are clustered and appeared to be transcribed as polycistronic messengers. To promote transcription of its genes, SIRV1 was shown to co-opt host-encoded transcription activator Sta1, which displays a canonical winged HTH (helix–turn–helix) fold [33]. Another candidate involved in viral gene expression is P56b (SvtR) that, in experiments in vitro, repressed transcription from several viral promoters including the promoters of its own gene and the gene for the largest structural protein, P1070 [34]. The NMR structure of the protein revealed a typical RHH (ribbon–helix–helix) fold; it has been shown that P56b forms a dimer (Figure 2) and binds DNA with its β-sheet face [34].

In addition to P56b, several other putative DNA-binding proteins were predicted by structural (summarized in [35]) and comparative genomics approaches [29] (Supplementary Table S1). These include P83a/83b (HTH motif), P59b (RHH motif), P55 (zinc-binding domain) and P114 (Table 1). Although the exact function of these proteins has yet to be determined, the presence of typical DNA-binding domains suggests that they might be involved in the regulation of viral and/or cellular promoters. The protein P114 is of special interest because it is highly conserved not only in rudiviruses and lipothrixviruses, but also in other diverse viruses of Crenarchaeota. This protein adopts a unique structural fold, and its homologues in lipothrixvirus AFV3 and STIV (Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus) were shown to bind dsDNA [36,37].

Table 1.

Functions encoded by the SIRV2 genome

| Role | Protein | GenBank® accession number | Evolutionary conservation* | Function | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virion structure | P134 | NP_666560 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses; structural homologues in lipothrixviruses | Major capsid protein | Experimental evidence |

| P488 | NP_666567 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses; no other detectable homologues | Structural protein | Experimental evidence | |

| P1070 | NP_666572 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses; middle coiled-coil domains similar to the coiled-coil domains of Smc protein involved in chromosome segregation | Structural protein; terminal fibres | Experimental evidence | |

| P564 | NP_666573 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses; more distant homologues in lipothrixviruses and several archaea | Structural protein | Experimental evidence | |

| DNA binding and transcriptional control | P56b (SvtR) | NP_666549 | Among rudiviruses, clear orthologue only in SIRV1; distant homologues in other archaeal viruses; significant similarity to numerous homologues from bacteria and some archaea; RHH domain | Transcriptional regulator | Experimental evidence |

| P83a/P83b | NP_666535/NP_666588 | Homologues in all rudiviruses except ARV1. Homologous with oligomerization domains of carbamoyl phosphate synthases (mostly bacterial); HTH domain | DNA-binding and/or protein oligomerization | Structural similarity | |

| P59b | NP_666555 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses, other archaeal viruses, archaea and bacteria; RHH domain | DNA-binding protein | In silico analysis | |

| P55 | NP_666561 | Among rudiviruses, conserved only in SIRV1 and SIRV2; more distant homologues in Thermococcus prieurii virus 1 and fusellovirus SSV7 (Sulfolobus spindle-shaped virus 7); significant similarity to eukaryotic zinc-finger proteins, particularly transcription factors; C2H2 zinc finger | DNA-binding protein | In silico analysis | |

| P114 | NP_666571 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses, lipothrixviruses and other archaeal viruses; more distant homologues in diverse bacteria; unique protein fold | DNA-binding protein | Structural similarity | |

| Genome replication | P119c | NP_666550 | Conserved in all rudiviruses; distant similarity to tyrosine transposases and Rep proteins; conserved motifs required for endonuclease activity | Replication initiator | Experimental evidence |

| P121 | NP_666569 | Conserved in all rudiviruses; strong similarity to archaeal Hjrs | Hjr | Experimental evidence | |

| Nucleic acid metabolism | P158b | NP_666557 | Only in SIRV1 and SIRV2 among the rudiviruses. A highly conserved homologue in STSV1 (Bicaudaviridae) and numerous archaea and bacteria | dUTPase | Experimental evidence |

| P207 | NP_666553 | Only in SIRV1 and SIRV2 among the rudiviruses, but also in some other archaeal viruses. Homologous with the Cas4 protein of the CRISPR–Cas antivirus immunity systems | ssDNA-specific endonuclease | Experimental evidence | |

| Virion egress | P98 | NP_666583 | Homologues in STIV and all rudiviruses except for ARV1 | Formation of VAPs | Experimental evidence |

| Covalent modification of various substrates | P356 | NP_666578 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses and in diverse bacteria. More distant homologues in other viruses | GTase | In silico analysis |

| P335 | NP_666562 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses and in diverse archaea and bacteria. More distant homologues in other viruses | GTase | In silico analysis | |

| P176 | NP_666577 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses and lipothrixviruses; distant similarity to bacterial GTases | GTase | In silico analysis | |

| P154 | NP_666568 | Highly conserved homologues only in SIRV1, SIRV2 and SRV; limited similarity to numerous acetyltransferases of the GCN5 family | Protein acetyltransferase | In silico analysis | |

| P310 | NP_666547 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses (except for ARV1), STSV1 and most archaea | Queuine/archaeosine tRNA-ribosyltransferase | In silico analysis | |

| P158a | NP_666575 | Highly conserved homologues in all rudiviruses and lipothrixviruses; more distant homologues in numerous archaea and bacteria | AdoMet (S-adenosylmethionine)-dependent (RNA) methyltransferase | In silico analysis | |

| Other | P399 | NP_666548 | Among rudiviruses, only in SIRV1 and SIRV2; moderately conserved homologues in numerous bacteria | Amino acid transporter | In silico analysis |

| P436 | NP_666552 | Homologues in all rudiviruses, some lipothrixviruses and in bacteria (ATPase domains of Lon proteases) | AAA + (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) | In silico analysis |

For details, see Supplementary Table S1 at http://www.biochemsoctrans.org/bst/041/bst0410443add.htm.

Viral cycle and virion egress

Owing to the absence of visible indications of cell lysis, it was originally presumed that rudiviruses are not lytic [9]. This view has been challenged by the recent in-depth analysis of SIRV2–Sulfolobus interactions [38]. Unexpectedly, massive degradation of the host chromosome was detected starting from early stages of infection. This was followed by virion assembly in the cytoplasm, in the form of several (three or four) densely packed bundles of approximately 50 virions, arranged side by side. Parallel to the virion assembly, heptagonal pyramidal formations, termed VAPs (virus-associated pyramids), are formed at the cell surface, rupturing the S-layer and pointing outwards [38]. The virus cycle ends with opening of the VAPs, allowing release of the cytoplasm and mature virions.

The VAPs could be isolated as stable structural units, hollow baseless pyramids with seven faces (isosceles triangles with angles of 74° and 33°) from the membrane fraction of SIRV2-infected cells [39]. These structures have been shown to consist solely of multiple copies of a single SIRV2 protein, P98 [39,40], which is predicted to be a type II membrane protein [40] and is self-sufficient for formation of pyramidal structures with sevenfold symmetry [39]. One member of the Rudividae, ARV1 [12], does not encode a P98 homologue and apparently exploits a different, currently unclear, mechanism of virion egress. Surprisingly, a homologue of P98 is present in STIV that has been shown to exploit a virion egress mechanism similar to that of rudiviruses [2,41,42]. Conceivably, these findings reflect independent evolution of virion morphogenesis and egress systems in archaeal viruses.

Covalent modification of various substrates and other functions

DNA viruses often encode proteins that are responsible for covalent modification of various cellular or viral substrates. These functions are likely to play important roles in modulating virus–host interactions at all stages of the infection cycle and are usually derived from the host genome, judging from typically high sequence similarity to and abundance of cellular homologues [29,43]. Among archaeal viruses, perhaps the most prevalent class of modification-conferring enzyme is GTases (glycosyltransferases). These enzymes are encoded by both euryarchaeal (e.g. His1) [44] and various crenarchaeal viruses [29], including the recently described Aeropyrum coil-shaped virus with a single-stranded DNA genome [10]. Genomes of members of the Ligamenvirales are particularly enriched in GTase-encoding genes, although the exact number varies among these viruses. SIRV2 encodes three GTases (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1), whereas the lipothrixvirus SIFV (Sulfolobus islandicus filamentous virus) encodes five. The three GTases of SIRV2 do not seem to have evolved via recent duplications; rather, each is represented by highly conserved orthologues in all known rudiviruses and, accordingly, all three can be inferred to be ancestral in this virus family. Moreover, the ultimate origins of these GTase might be different, with one of them (P356) being of apparent bacterial provenance. To date, none of the GTases encoded by archaeal viruses has been functionally characterized. However, irrespective of the presence of a GTase gene in a viral genome, it has been demonstrated that structural proteins of archaeal viruses are often glycosylated [45–47]. The same is true for rudivirus ARV1, the major capsid protein of which has been shown to be sugar-modified [12]. Besides virion proteins, GTases might also be responsible for modification of viral genomes, cellular proteins or host cell envelope. However, the latter modifications remain to be investigated.

In addition to the GTases, SIRV2 encodes three other predicted enzymes potentially involved in modification of various substrates (Table 1). These include a protein acetyltransferase and two RNA-modifying enzymes, namely tRNA-ribosyltransferase (also a member of the GTase superfamily) and S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyl-transferase. Close homologues of the last two proteins are widespread in archaea and are also conserved in lipothrixviruses. In addition, a homologue of the SIRV2 tRNA-ribosyltransferase is encoded by STSV1 [48], a tentative member of the Bicaudaviridae family. An apparent function for these proteins is modification of (certain) cellular tRNAs, with consequent potential role in decoding, translation accuracy and control, as well as structural integrity of tRNAs [49].

Finally, SIRV2 encodes two additional proteins that could play important roles during the infection cycle. Protein P436 possesses an AAA + (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) domain, most closely related to the ATPase domains of ATP-dependent Lon proteases. However, the function of this protein remains enigmatic. Protein P399 possesses 12 transmembrane domains and is homologous with amino acid transporters (Supplementary Table S1). This protein could be important for securing the supply of amino acids for virus propagation and virion assembly, a process which might be compromised as a result of degradation of the cellular chromosome [38]. Interestingly, beyond the rudiviruses, both of these proteins have primarily bacterial, but not archaeal, homologues, emphasizing the apparent bacterial contribution to the evolution of archaeal viruses.

Conclusions

Properties of approximately half of the proteins encoded by the rudiviruses SIRV1 and SIRV2 have been characterized as a result of analysis of their sequences, structures and biochemical characteristics (Table 1). Such a proportion of recognized gene functions is among the highest for crenarchaeal viruses. The discovery of the unique egress mechanism of rudiviruses suggests that the wealth of information on molecular aspects of virus–host interactions from the two other domains of life, Bacteria and Eukarya, is of limited value for the rudiviruses, and perhaps generally for archaeal viruses. Major questions remain to be answered, particularly the following. (i) How do rudiviruses deliver DNA into the host cell? (ii) How is the host replication machinery recruited for preferential production of viral genomes? (iii) How do viral proteins achieve dramatic changes in the host cell leading to the elimination of the host chromosome and establishment of viral factory? (iv) What are the requirements and molecular mechanisms that allow incorporation of rudiviral gene fragments (protospacers) into CRISPR loci of Sulfolobales [50,51]? (v) What drives the assembly of individual virions as well as virion bundles in the cytoplasm of the host cell? (vi) How do rudiviruses achieve well-orchestrated opening of the virion release structures, VAPs, and extrusion of linear virions through the perforations? Answering these questions and deciphering molecular details of the life cycle of rudiviruses promises to unravel unknown aspects of virus–host interaction and could provide novel insights into the origin and evolution of viruses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to all past and present laboratory members and all collaborators who have contributed to the studies described in the present review.

Funding

E.V.K. is supported by the intramural funds of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (to the National Library of Medicine).

Abbreviations used

- AFV

Acidianus filamentous virus

- ARV1

Acidianus rod-shaped virus 1

- CRISPR

cluster of regularly interspaced palindromic repeats

- Cas

CRISPR-associated sequences

- ds

double-stranded

- GTase

glycosyltransferase

- Hjr

Holliday junction resolvase

- HTH

helix–turn–helix

- ITR

inverted terminal repeat

- MCP

major capsid protein

- ORF

open reading frame

- RHH

ribbon–helix–helix

- SIRV

Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus

- SRV

Stygiolobus rod-shaped virus

- ss

single-stranded

- STIV

Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus

- STSV1

Sulfolobus tengchongensis spindle-shaped virus 1

- VAP

virus-associated pyramid

References

- 1.Pina M, Bize A, Forterre P, Prangishvili D. The archeoviruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:1035–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu CY, Johnson JE. Structure and cell biology of archaeal virus STIV. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iverson E, Stedman K. A genetic study of SSV1, the prototypical fusellovirus. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirth JF, Snyder JC, Hochstein RA, Ortmann AC, Willits DA, Douglas T, Young MJ. Development of a genetic system for the archaeal virus Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus (STIV) Virology. 2011;415:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R, Rossler N, Iro M, Scholz H, Witte A. Haloarchaeal myovirus phiCh1 harbours a phase variation system for the production of protein variants with distinct cell surface adhesion specificities. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:137–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roine E, Oksanen HM. Viruses from the hypersaline environment. In: Ventosa A, Oren A, Ma Y, editors. Halophiles and Hypersaline Environments: Current Research and Future Trends. Springer; Berlin: 2011. pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senčilo A, Paulin L, Kellner S, Helm M, Roine E. Related haloarchaeal pleomorphic viruses contain different genome types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5523–5534. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter K, Dyall-Smith ML. Transfection of haloarchaea by the DNAs of spindle and round haloviruses and the use of transposon mutagenesis to identify non-essential regions. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:1236–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prangishvili D, Arnold HP, Gotz D, Ziese U, Holz I, Kristjansson JK, Zillig W. A novel virus family, the Rudiviridae: structure, virus–host interactions and genome variability of the Sulfolobus viruses SIRV1 and SIRV2. Genetics. 1999;152:1387–1396. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochizuki T, Krupovic M, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Sako Y, Forterre P, Prangishvili D. Archaeal virus with exceptional virion architecture and the largest single-stranded DNA genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13386–13391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203668109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prangishvili D, Krupovic M. A new proposed taxon for double-stranded DNA viruses, the order “Ligamenvirales”. Arch Virol. 2012;157:791–795. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestergaard G, Haring M, Peng X, Rachel R, Garrett RA, Prangishvili D. A novel rudivirus, ARV1, of the hyperthermophilic archaeal genus Acidianus. Virology. 2005;336:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vestergaard G, Shah SA, Bize A, Reitberger W, Reuter M, Phan H, Briegel A, Rachel R, Garrett RA, Prangishvili D. Stygiolobus rod-shaped virus and the interplay of crenarchaeal rudiviruses with the CRISPR antiviral system. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6837–6845. doi: 10.1128/JB.00795-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rakonjac J, Bennett NJ, Spagnuolo J, Gagic D, Russel M. Filamentous bacteriophage: biology, phage display and nanotechnology applications. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2011;13:51–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelloniemi J, Makinen K, Valkonen JP. Three heterologous proteins simultaneously expressed from a chimeric potyvirus: infectivity, stability and the correlation of genome and virion lengths. Virus Res. 2008;135:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szymczyna BR, Taurog RE, Young MJ, Snyder JC, Johnson JE, Williamson JR. Synergy of NMR, computation, and X-ray crystallography for structural biology. Structure. 2009;17:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupovic M, Bamford DH. Double-stranded DNA viruses: 20 families and only five different architectural principles for virion assembly. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goulet A, Blangy S, Redder P, Prangishvili D, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Forterre P, Campanacci V, Cambillau C. Acidianus filamentous virus 1 coat proteins display a helical fold spanning the filamentous archaeal viruses lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21155–21160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909893106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinmetz NF, Bize A, Findlay KC, Lomonossoff GP, Manchester M, Evans DJ, Prangishvili D. Site-specific and spatially controlled addressability of a new viral nanobuilding block: Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus 2. Adv Funct Mater. 2008;18:2478–3486. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum H, Zillig W, Mallok S, Domdey H, Prangishvili D. The genome of the archaeal virus SIRV1 has features in common with genomes of eukaryal viruses. Virology. 2001;281:6–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng X, Blum H, She Q, Mallok S, Brugger K, Garrett RA, Zillig W, Prangishvili D. Sequences and replication of genomes of the archaeal rudiviruses SIRV1 and SIRV2: relationships to the archaeal lipothrixvirus SIFV and some eukaryal viruses. Virology. 2001;291:226–234. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prangishvili D. Evolutionary insights from studies on viruses of hyperthermophilic archaea. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:289–294. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oke M, Kerou M, Liu H, Peng X, Garrett RA, Prangishvili D, Naismith JH, White MF. A dimeric Rep protein initiates replication of a linear archaeal virus genome: implications for the Rep mechanism and viral replication. J Virol. 2011;85:925–931. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01467-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oke M, Carter LG, Johnson KA, Liu H, McMahon SA, Yan X, Kerou M, Weikart ND, Kadi N, Sheikh MA, et al. The Scottish Structural Proteomics Facility: targets, methods and outputs. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2010;11:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilyina TV, Koonin EV. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3279–3285. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messing SA, Ton-Hoang B, Hickman AB, McCubbin AJ, Peaslee GF, Ghirlando R, Chandler M, Dyda F. The processing of repetitive extragenic palindromes: the structure of a repetitive extragenic palindrome bound to its associated nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9964–9979. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birkenbihl RP, Neef K, Prangishvili D, Kemper B. Holliday junction resolving enzymes of archaeal viruses SIRV1 and SIRV2. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:1067–1076. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prangishvili D, Klenk HP, Jakobs G, Schmiechen A, Hanselmann C, Holz I, Zillig W. Biochemical and phylogenetic characterization of the dUTPase from the archaeal virus SIRV. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6024–6029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prangishvili D, Garrett RA, Koonin EV. Evolutionary genomics of archaeal viruses: unique viral genomes in the third domain of life. Virus Res. 2006;117:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardner AF, Prangishvili D, Jack WE. Characterization of Sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus 2 gp19, a single-strand specific endonuclease. Extremophiles. 2011;15:619–624. doi: 10.1007/s00792-011-0385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Wolf YI, Yakunin AF, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler A, Brinkman AB, van der Oost J, Prangishvili D. Transcription of the rod-shaped viruses SIRV1 and SIRV2 of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7745–7753. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7745-7753.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler A, Sezonov G, Guijarro JI, Desnoues N, Rose T, Delepierre M, Bell SD, Prangishvili D. A novel archaeal regulatory protein, Sta1, activates transcription from viral promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4837–4845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guilliere F, Peixeiro N, Kessler A, Raynal B, Desnoues N, Keller J, Delepierre M, Prangishvili D, Sezonov G, Guijarro JI. Structure, function, and targets of the transcriptional regulator SvtR from the hyperthermophilic archaeal virus SIRV1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22222–22237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.029850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krupovic M, White MF, Forterre P, Prangishvili D. Postcards from the edge: structural genomics of archaeal viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2012;82:33–62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394621-8.00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller J, Leulliot N, Cambillau C, Campanacci V, Porciero S, Prangishvili D, Forterre P, Cortez D, Quevillon-Cheruel S, van Tilbeurgh H. Crystal structure of AFV3-109, a highly conserved protein from crenarchaeal viruses. Virol J. 2007;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larson ET, Eilers BJ, Reiter D, Ortmann AC, Young MJ, Lawrence CM. A new DNA binding protein highly conserved in diverse crenarchaeal viruses. Virology. 2007;363:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bize A, Karlsson EA, Ekefjard K, Quax TE, Pina M, Prevost MC, Forterre P, Tenaillon O, Bernander R, Prangishvili D. A unique virus release mechanism in the Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11306–11311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901238106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quax TE, Lucas S, Reimann J, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Prevost MC, Forterre P, Albers SV, Prangishvili D. Simple and elegant design of a virion egress structure in Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3354–3359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quax TE, Krupovic M, Lucas S, Forterre P, Prangishvili D. The Sulfolobus rod-shaped virus 2 encodes a prominent structural component of the unique virion release system in Archaea. Virology. 2010;404:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brumfield SK, Ortmann AC, Ruigrok V, Suci P, Douglas T, Young MJ. Particle assembly and ultrastructural features associated with replication of the lytic archaeal virus Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus. J Virol. 2009;83:5964–5970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02668-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder JC, Brumfield SK, Peng N, She Q, Young MJ. Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus c92 protein responsible for the formation of pyramid-like cellular lysis structures. J Virol. 2011;85:6287–6292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00379-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krupovic M, Prangishvili D, Hendrix RW, Bamford DH. Genomics of bacterial and archaeal viruses: dynamics within the prokaryotic virosphere. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:610–635. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bath C, Dyall-Smith ML. His1, an archaeal virus of the Fuselloviridae family that infects Haloarcula hispanica. J Virol. 1998;72:9392–9395. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9392-9395.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kandiba L, Aitio O, Helin J, Guan Z, Permi P, Bamford DH, Eichler J, Roine E. Diversity in prokaryotic glycosylation: an archaeal-derived N-linked glycan contains legionaminic acid. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:578–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maaty WS, Ortmann AC, Dlakic M, Schulstad K, Hilmer JK, Liepold L, Weidenheft B, Khayat R, Douglas T, Young MJ, Bothner B. Characterization of the archaeal thermophile Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus validates an evolutionary link among double-stranded DNA viruses from all domains of life. J Virol. 2006;80:7625–7635. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00522-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mochizuki T, Yoshida T, Tanaka R, Forterre P, Sako Y, Prangishvili D. Diversity of viruses of the hyperthermophilic archaeal genus Aeropyrum, and isolation of the Aeropyrum pernix bacilliform virus 1, APBV1, the first representative of the family Clavaviridae. Virology. 2010;402:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiang X, Chen L, Huang X, Luo Y, She Q, Huang L. Sulfolobus tengchongensis spindle-shaped virus STSV1: virus–host interactions and genomic features. J Virol. 2005;79:8677–8686. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8677-8686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips G, de Crécy-Lagard V. Biosynthesis and function of tRNA modifications in Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo L, Brugger K, Liu C, Shah SA, Zheng H, Zhu Y, Wang S, Lillestol RK, Chen L, Frank J, et al. Genome analyses of Icelandic strains of Sulfolobus islandicus, model organisms for genetic and virus–host interaction studies. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1672–1680. doi: 10.1128/JB.01487-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You XY, Liu C, Wang SY, Jiang CY, Shah SA, Prangishvili D, She Q, Liu SJ, Garrett RA. Genomic analysis of Acidianus hospitalis W1 a host for studying crenarchaeal virus and plasmid life cycles. Extremophiles. 2011;15:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s00792-011-0379-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.