Description

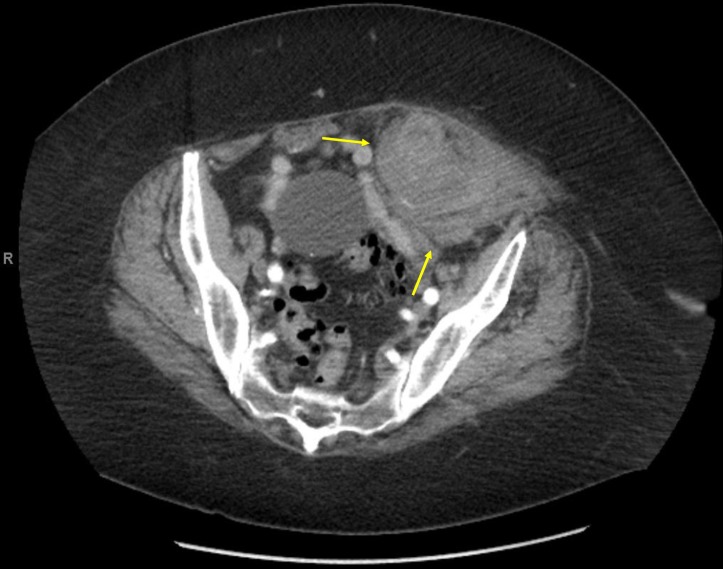

A 69-year-old woman on apixaban for 4 years due to her atrial fibrillation presented with severe left lower abdominal pain. She was discharged from the hospital 4 days prior after treatment for influenza and had finished a course of oseltamivir. She did not receive any heparin products and was continued on apixaban during that admission. A few hours before presentation, she reported coughing severely with sudden onset of excruciating abdominal pain. She denied trauma or injury to the abdomen. On exam, she was alert, normotensive and tachycardic, with significant left lower quadrant tenderness in the abdomen. Laboratory results were significant for decreased haemoglobin from 15.2 to 12.9 g/dL. CT of the abdomen showed acute left inferior rectus abdominis muscle haematoma (7.5 cm), along with stable and unchanged left adnexal cystic lesion (figure 1). Apixaban was discontinued, and the patient was closely monitored in the hospital with supportive care. Her haemoglobin remained stable and her pain improved. Repeat CT showed stable rectus sheath haematoma. She was asked to withhold apixaban for 1 week and was discharged to follow-up with her primary care physician to restart it.

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen showing acute left inferior rectus abdominis muscle haematoma measuring 7.5 cm (arrows), along with stable and unchanged left adnexal cystic lesion.

About one in six emergency department visits for adverse drug events is due to bleeding in patients taking anticoagulant medications, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) account for 10% of these events.1 Only four cases of DOAC-associated rectus sheath haematoma have been reported, two associated with apixaban and two with rivaroxaban.2 Rectus sheath haematoma is a rare but serious complication associated with significant morbidity and occasional mortality. It is the result of bleeding into the rectus sheath from damage to the superior or inferior epigastric arteries. Common risk factors and causes of rectus sheath haematoma include anticoagulation, blunt or penetrating trauma, pregnancy, female gender, older age, hypertension, medical conditions such as collagen vascular disorders, and increased abdominal pressure from straining or severe coughing.2 Ultrasound is the initial test of choice, but CT of the abdomen will help to identify the origin, location and extent of bleeding. Management of rectus sheath haematoma depends on several factors such as the severity and size of the haematoma, the haemodynamic status of the patient and the extent of anticoagulation. Treatment includes usual supportive measures, including interventional source control when indicated.2 No guidelines exist to direct the timing of anticoagulation resumption in patients with spontaneous rectus sheath haematomas. The requirement for anticoagulation should be weighed against the risk of rebleeding once the haematoma is stable. For severe DOAC-related bleeding, prothrombin complex concentrate and recombinant activated factor VII have been recommended.1 Current research focuses on antidotes to neutralise the anticoagulant activity of DOACs, including both direct thrombin inhibitors and direct factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors. Idarucizumab is licensed for the rapid reversal of the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran in the setting of life-threatening bleeding. Andexanet alfa is an investigational drug being developed as a reversal agent for anti-FXa DOACs (apixaban, betrixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban), and ciraparantag is another investigational drug being developed as a universal antidote to reverse all DOACs.3

Learning points.

Rectus sheath haematoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients on anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants, who present with acute abdominal pain particularly after rigorous coughing.

Ultrasound is usually the initial diagnostic test, but CT might be necessary to determine the origin and source of a rectus sheath haematoma.

The primary treatment for rectus sheath haematoma is supportive care, but interventional radiology-guided vascular embolisation or surgical repair may be warranted in severe cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Scott Kaatz for critical review of this manuscript and Ms. Sarah Whitehouse for language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: KE is the primary author and was responsible for data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and manuscript preparation. SM participated in manuscript preparation and editing. JD participated in data interpretation and manuscript evaluation. KG supervised the development of the manuscript and final evaluation. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kaatz S, Mahan CE, Nakhle A, et al. Management of elective surgery and emergent bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19:124 10.1007/s11886-017-0930-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunasekaran K, Winans ARM, Murthi S, et al. Rectus sheath hematoma associated with apixaban. Clin Pract 2017;7:957 10.4081/cp.2017.957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnett A, Siegal D, Crowther M. Specific antidotes for bleeding associated with direct oral anticoagulants. BMJ 2017;357:j2216 10.1136/bmj.j2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]