Abstract

Objectives

Immigrants are thought to be healthier than their native-born counterparts, but less is known about the health of refugees or forced migrants. Previous studies often equate refugee status with immigration status or country of birth (COB) and none have compared refugee to non-refugee immigrants from the same COB. Herein, we examined whether: (1) a refugee mother experiences greater odds of adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes compared with a similar non-refugee mother from the same COB and (2) refugee and non-refugee immigrants differ from Canadian-born mothers for maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Design

This is a retrospective population-based database study. We implemented two cohort designs: (1) 1:1 matching of refugees to non-refugee immigrants on COB, year and age at arrival (±5 years) and (2) an unmatched design using all data.

Setting and participants

Refugee immigrant mothers (n=34 233), non-refugee immigrant mothers (n=243 439) and Canadian-born mothers (n=615 394) eligible for universal healthcare insurance who had a hospital birth in Ontario, Canada, between 2002 and 2014.

Primary outcomes

Numerous adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes.

Results

Refugees differed from non-refugee immigrants most notably for HIV, with respective rates of 0.39% and 0.20% and an adjusted OR (AOR) of 1.82 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.79). Other elevated outcomes included caesarean section (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08) and moderate preterm birth (AOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.17). For the majority of outcomes, refugee and non-refugee immigrants experienced similar AORs when compared with Canadian-born mothers.

Conclusions

Refugee status was associated with a few adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes, but the associations were not strong except for HIV. The definition of refugee status used herein may not sensitively identify refugees at highest risk. Future research would benefit from further refining refugee status based on migration experiences.

Keywords: epidemiology, maternal medicine, perinatology, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a retrospective population-based cohort study from Ontario, Canada, linking official permanent resident immigration, hospital and physician billing data to compare births between 2002 and 2014 from refugee mothers (n=34 233) to both non-refugee immigrant mothers (n=243 439) and Canadian-born mothers (n=615 394).

This is the first study to match refugee immigrant to non-refugee immigrant mothers on country of birth, year and age at arrival; making it possible to explicitly determine whether refugee status confers greater risk of adverse outcomes among two otherwise very similar mothers.

This is one of the largest studies of refugee maternal and perinatal health in the literature.

The administrative definition of refugee status used in this study may not be sensitive enough to identify refugees with greater health risks or greater healthcare needs.

Introduction

Refugees are considered an extremely vulnerable group for adverse health outcomes.1 Canada and other signatories to the United Nations (UN) Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees define refugees as persons who fear persecution or violence because of their race, religion, nationality or political views and are forced to flee their home countries.2 In Canada, 10% of the 250 000 immigrants who become permanent residents each year are admitted as refugees.3 Most non-refugee permanent residents are selected based on high levels of education, official language fluency and work experience, or are related to a permanent resident or Canadian citizen. This is in contrast to refugees who are either chosen based on vulnerability by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or claim refugee status on arrival and have the claim accepted by an independent tribunal.4

Given differing exposures in: countries of origin (eg, conflict), transition countries (eg, poor access to health services), postmigration exposures (eg, discrimination) and receiving country immigration policies, the maternal and perinatal health of refugees may differ from their non-refugee immigrant counterparts.5 6

Few refugee maternal and perinatal health studies in Canada5–8 or in other countries9 compare refugees to non-refugee immigrants. Many studies use a native-born comparator and attribute excess risk to refugee status even though a non-refugee immigrant comparator is absent.10–15 In addition, many studies rely on country of birth (COB) as an indicator of refugee migration11–18 rather than identifying refugees based on their legal status or migration history. These details are critical, since specialised maternal and perinatal healthcare tailored to refugees cannot be effectively justified if a ‘refugee effect’ cannot be differentiated from an ‘immigrant effect’ or ‘country effect’. In addition, research often finds that immigrants are healthier than the native-born population, the so-called ‘healthy migrant effect’ (HME).19 However, the effect may not apply to refugees given their differential exposure to health risks prior to arrival (as described earlier in the Introduction). Studies are mixed as to whether the HME applies to refugee maternal and perinatal health.5 6 12

Given this background, our first objective was to determine whether a refugee immigrant mother experiences greater odds of adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes compared with a similar non-refugee immigrant mother from the same COB. Secondary analyses focused on the top five refugee source countries (Sri Lanka, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iran and China). Second, we compared maternal and perinatal health outcomes among refugee and non-refugee immigrant mothers to Canadian-born mothers to examine whether the HME applies to both refugee and non-refugee immigrants. This study used population-based administrative healthcare and immigration data from Ontario, the province which receives about half of all refugees arriving to Canada.3

Methods

Study design and inclusion/exclusion criteria

This retrospective population-based database study included all Ontario hospital childbirth admissions occurring between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2014. A matched cohort design was used to isolate the excess risk conferred by refugee status beyond that of immigration and COB, while a non-matched cohort design used all available data to compare outcomes of refugee and non-refugee immigrants to Canadian-born mothers. Births to refugee and non-refugee immigrant mothers were identified retrospectively through linkage of hospital admissions to the Immigration and Refugees Citizenship Canada Permanent Resident Database (IRCC-PRD). The cost of healthcare services was not a barrier to accessing care since all mothers were eligible for universal, publicly funded healthcare insurance. Births not linked to the IRCC-PRD were attributed to Canadian-born mothers (Indigenous mothers could not be excluded at the time of the linkage). We reduced the bias attributed to unlinked migrant mothers among Canadian-born mothers by further restricting to mothers who: (1) became eligible for provincial healthcare insurance on or before 1990 (the first-year insurance eligibility was recorded—those eligible prior to 1990 were given an eligibility start year of 1990) and less likely to be immigrants; (2) were born in an Ontario hospital after 1991 (the first-year births were available in hospital data) or (3) became eligible for provincial healthcare insurance within 1 year of their year of birth and therefore lived in Ontario from a very young age.

For maternal outcomes, the unit of analysis was the delivery episode, where multiple births were counted as a single delivery. For all perinatal outcomes, the unit of analysis was restricted to singletons. Since many of the outcomes in this study are commonly used in epidemiological surveillance, specifications based on gestational age (GA) and/or birth weight (BWT) used by the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System20 were implemented where possible. These specifications relate to including births that are reasonably expected to be at risk for the outcome; births <500 g and/or <20 weeks gestation are less likely to be viable. The populations were as follows: preterm birth (PTB)—live births between 22 and 41 weeks GA and a BWT of ≥500 g; neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission—live births with GA ≥20 weeks or a BWT ≥500 g; neonatal mortality—live births with a BWT ≥500 g; any congenital anomaly—stillbirths and live births with a GA ≥20 weeks or a BWT ≥500 g; stillbirth—GA ≥20 weeks or a BWT ≥500 g; perinatal mortality—stillbirths and live births with a GA ≥20 weeks or a BWT ≥500 g.

Data sources

We linked five administrative databases held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Toronto, Ontario. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers (ie, encrypted healthcare number) and analysed at ICES.

The IRCC-PRD is administered by the Canadian government and used for legal purposes. The Ontario portion of this dataset contains information on all international migrants successful in obtaining permanent residency between 1985 and 2012. The IRCC-PRD contained <1% of missing values for all variables. Linkage between the IRCC-PRD and Ontario’s healthcare registry was necessary to assign each individual in the IRCC-PRD, their unique encrypted healthcare number since this facilitated deterministic linkage to the healthcare databases used to identify outcomes of interest. Ontario’s healthcare registry consists of all persons eligible for publicly funded healthcare insurance in the province of Ontario between 1 April 1990 and 31 March 2014. The healthcare registry contains encrypted unique healthcare numbers and other personal identifiers. A detailed explanation of the process used to link the IRCC-PRD and Ontario’s healthcare registry can be found elsewhere.21 In summary, deterministic linkage was undertaken first using several personal identifiers (ie, sex, last name, given name, birth date) resulting in a 68.2% deterministic linkage rate. Unmatched records were then submitted to a probabilistic and manual review process which resulted in an additional 18.2% of records being linked (13.6% remained unlinked). Bias in the linkage process was investigated by comparing immigration variables between matched and unmatched individuals and little bias was detected.21

Childbirth records were obtained from the Discharge Abstract Database originating from the Canadian Institute of Health Information. Diagnosis and procedure codes using the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Canadian enhancement, and Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (ICD-10-CA/CCI) identified women with all maternal or perinatal outcomes except early neonatal and neonatal mortality. A validation study supported the use of this database for perinatal research.22 This dataset also contains information on maternal age at the time of delivery, self-reported parity and birth plurality.

The Office of the Registrar General’s Vital Statistics-Death registry was used to identify early neonatal mortality (0–7 days of life) and neonatal mortality (0–28 days of life) between 2002 and 2012. 96.2% of records in the Vital Statistics Registry were successfully linked to the healthcare registry and little bias in the linkage was detected.21 However, individuals between the ages of 0 and 14 years were more likely to be unlinked. Vital Statistics data were supplemented by mortality recorded in the healthcare registry and other administrative healthcare databases, however, early neonatal deaths may also be missing in the healthcare registry because healthcare numbers may not have been issued.21

The Ontario HIV Database (1992–2014) uses an algorithm consisting of at least three physician HIV diagnoses in a 3-year period to identify HIV-positive persons. The algorithm demonstrated 96.2% sensitivity and 99.6% specificity when compared with patient charts.23 HIV diagnoses were restricted to women diagnosed prior to childbirth.

Variables

Refugee status was defined using the IRCC-PRD. There are four categories of refugees in the database: (1) government sponsored refugees, who are provided with financial and settlement assistance during their first year in Canada by the federal government; (2) privately sponsored refugees, who are provided with financial and settlement assistance during their first year in Canada by a group of Canadians; (3) refugee claimants, who arrive to Canada unsupported and make a legal claim to refugee status and (4) refugees who are dependants of a primary refugee applicant. Prior to arrival, the two groups of sponsored refugees were registered with the UNHCR and are chosen for immigration to Canada based on vulnerability. Sponsored refugees become permanent residents and are eligible for provincial healthcare on arrival to Canada. Non-sponsored refugees (ie, refugee claimants)4 24 are eligible for federally funded healthcare (administered by the provinces) while they wait for their refugee determination hearing. The proportion of refugee claims approved during the time span of the IRCC-PRD is unknown, but recent data indicate approvals have risen from 38.1% in 2013 to 66.1% in 2016.25 Successful refugee claimants, who make up the remaining 50% of permanent residents who are refugees, become eligible for permanent residency and for provincial healthcare once their claim is approved. Unsuccessful refugee claimants are not included in the IRCC-PRD.

Non-refugee immigrants in the IRCC-PRD are predominately skilled immigrants or their family members. Skilled immigrants are selected based on high levels of education, official language fluency and work experience. Family class immigrants must be related to a permanent resident or Canadian citizen able to provide financial support. Soon after arrival in Canada both groups become permanent residents and are eligible for universal, provincially funded healthcare.

All immigrants in the IRCC-PRD were subject to an immigration medical examination during the application process. Prior to 2002 immigration applicants could be rejected if they placed ‘excessive demand’ on health and social services.26 However, in 2002 the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA)27 came into effect which changed this ‘excessive demand’ criteria, so it only applied to skilled immigrants and not family class immigrants or refugees.

Canadian-born women are described above (under ‘Study Design and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria’).

We examined several maternal and perinatal health outcomes (see online supplementary table S1 for codes). Severe maternal morbidity (SMM), was evaluated using a composite surveillance indicator,28 29 developed by the Canadian Perinatal Health Surveillance System. A woman had a SMM if she had one or more of 45 ICD-10-CA/CCI diagnoses or procedures reported during hospital admission for labour or delivery.28 Other maternal health outcomes, documented at the time of delivery, were: complicated urinary tract infection (UTI), pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, prepregnancy diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) and maternal intensive care unit admission. Perinatal outcomes, documented at birth, included: any congenital anomaly, moderate PTB (32–36 weeks gestation), very PTB (<32 weeks gestation), NICU admission and stillbirth. Measurements of early neonatal mortality (0–7 days of life) and neonatal mortality (0–28 days of life) were not restricted to the hospital delivery admission. Information from both the Office of the Registrar General’s Vital Statistics Death Registry and Ontario’s health care registry were combined to identify early neonatal and neonatal mortality. Early neonatal mortality was combined with information on stillbirth to identify perinatal mortality.

bmjopen-2017-018979supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

Potential confounders were identified a priori. Some control variables were available for all births, including maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40+ years), neighbourhood income quintile, parity (0, 1, 2 or ≥3 previous births) and plurality. Other control variables were only available for refugees and non-refugee immigrants since this information was collected in the IRCC-PRD. These included: maternal COB; COBs categorised into world regions and subregions according to the UN classification system with a modification to the developed countries classification30; year of arrival (5-year categories); age at arrival (5-year categories); maternal education at arrival (0–9 years, 10–12 years, 13+ years, trade certificate/non-university diploma, university degree); knowledge of official Canadian languages at arrival (English and/or French or neither) and duration of residence in Canada, defined as the time (in years) elapsed between the date of becoming a permanent resident and the date of delivery.

Analysis

Births with missing data for any control variable were excluded. To estimate whether refugee status increases the odds of adverse outcomes between a refugee mother and a non-refugee mother with similar premigration circumstances (objective 1), we 1:1 matched first births in Canada among refugees to non-refugee immigrants on COB, year of arrival (±5 years) and age at arrival (±5 years). Analyses were restricted to the first delivery in the hospitalisation database to prevent matching several births from a single refugee mother to births to more than one non-refugee immigrant mother. We conducted a matched pair analysis using conditional logistic regression. In secondary analyses focusing on refugee and non-refugee immigrants from each of the top five refugee-source countries of birth, all births were included and analysed with logistic regression. All the above models were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, parity, neighbourhood income, education at arrival, knowledge of official languages at arrival and duration of residence in Canada. In a sensitivity analysis, all births to refugee mothers were compared with all births to non-refugee mothers using logistic regression with generalised estimating equations (GEE) to account for the non-independence of the outcome among mothers from the same COB.

To compare refugee and non-refugee mothers to Canadian-born mothers, all births were included and logistic regression with GEE were used to account for non-independence of the outcome among births to the same mother. Fewer variables were available for Canadian-born women so models were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, parity and neighbourhood income.

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of refugee immigrant mothers (n=34 233), non-refugee immigrant mothers (n=243 439) and Canadian-born mothers (n=615 394). Refugee mothers had 52 360 births in Ontario, non-refugee immigrant mothers had 360 007 births and Canadian mothers had 977 045 births. More refugee mothers (10%) had high parity (≥3 previous births) compared with both non-refugee immigrant (3.2%) and Canadian-born mothers (2.7%) at the first birth in Ontario. A greater proportion of refugees had less than 13 years of education at arrival (72.6%) compared with non-refugee immigrants (43.0%). There were about five times as many refugee mothers from Sub-Saharan Africa compared with non-refugee immigrant mothers (22.8% and 4.8%, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of refugee immigrant, non-refugee immigrant and Canadian-born mothers in Ontario, Canada 2002–2014

| Refugee immigrant (n=34 233) |

Non-refugee immigrant (n=243 439) |

Canadian-born (n=615 394) |

|

| Maternal age at first birth, years | |||

| 15–19 | 989 (2.9) | 3469 (1.4) | 40 905 (6.6) |

| 20–24 | 5271 (15.4) | 30 330 (12.5) | 98 808 (16.1) |

| 25–29 | 10 231 (29.9) | 75 982 (31.2) | 180 850 (29.4) |

| 30–34 | 10 032 (29.3) | 79 885 (32.8) | 191 433 (31.1) |

| 35–39 | 5958 (17.4) | 42 893 (17.6) | 84 383 (13.7) |

| ≥40 | 1742 (5.1) | 10 843 (4.5) | 18 624 (3.0) |

| Missing | 10 (0.0) | 37 (0.0) | 391 (0.1) |

| Parity at first birth in Ontario | |||

| 0 | 18 826 (55.0) | 152 530 (62.7) | 445 715 (72.4) |

| 1 | 7631 (22.3) | 62 708 (25.8) | 109 462 (17.8) |

| 2 | 4317 (12.6) | 20 091 (8.3) | 42 656 (6.9) |

| ≥3 | 3421 (10.0) | 7892 (3.2) | 16 635 (2.7) |

| Missing | 38 (0.1) | 218 (0.1) | 926 (0.2) |

| No of births in Ontario | |||

| 1 | 20 406 (59.6) | 148 694 (61.1) | 328 458 (53.4) |

| 2 | 10 356 (30.3) | 76 411 (31.4) | 225 838 (36.7) |

| 3 | 2800 (8.2) | 15 473 (6.4) | 50 262 (8.2) |

| ≥4 | 671 (2.0) | 2861 (1.2) | 10 836 (1.8) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 15 332 (44.8) | 78 309 (32.2) | 111 281 (18.1) |

| 2, 3, 4 (middle) | 16 804 (49.1) | 141 357 (58.1) | 386 578 (62.8) |

| 5 (highest) | 2001 (5.8) | 22 926 (9.4) | 113 769 (18.5) |

| Missing | 96 (0.3) | 847 (0.3) | 3766 (0.6) |

| Official language ability at immigration | |||

| English and/or French | 19 633 (57.4) | 157 788 (64.8) | – |

| Neither English or French | 14 600 (42.6) | 85 645 (35.2) | – |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.0) | – |

| Level of education at immigration | |||

| 0–9 years | 14 923 (43.6) | 56 485 (23.2) | – |

| 10–12 years | 9931 (29.0) | 48 137 (19.8) | – |

| ≥13 years | 3010 (8.8) | 22 380 (9.2) | – |

| Trade, diplomas | 3720 (10.9) | 30 852 (12.7) | – |

| Bachelors, masters, doctorate | 2649 (7.7) | 85 585 (35.2) | – |

| Duration of residence, years | |||

| <10 | 21 569 (63.0) | 184 508 (75.8) | – |

| ≥10 | 12 664 (37.0) | 58 931 (24.2) | – |

| World region of birth | |||

| South Asia | 9233 (27.0) | 78 184 (32.1) | – |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7810 (22.8) | 11 733 (4.8) | – |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 4928 (14.4) | 33 075 (13.6) | – |

| Western and Central Asia, North Africa | 3458 (10.1) | 17 502 (7.2) | – |

| Eastern Europe | 3189 (9.3) | 18 542 (7.6) | – |

| Southeast Asia, Oceania Islands | 1514 (4.4) | 28 514 (11.7) | – |

| East Asia (excluding Japan) | 1878 (5.5) | 35 669 (14.7) | – |

| Southern Europe | 1966 (25.1) | 8003 (30.8) | – |

| Developed countries | 250 (22.4) | 12 152 (25.5) | – |

| Missing | 7 (0.0) | 65 (0.0) | – |

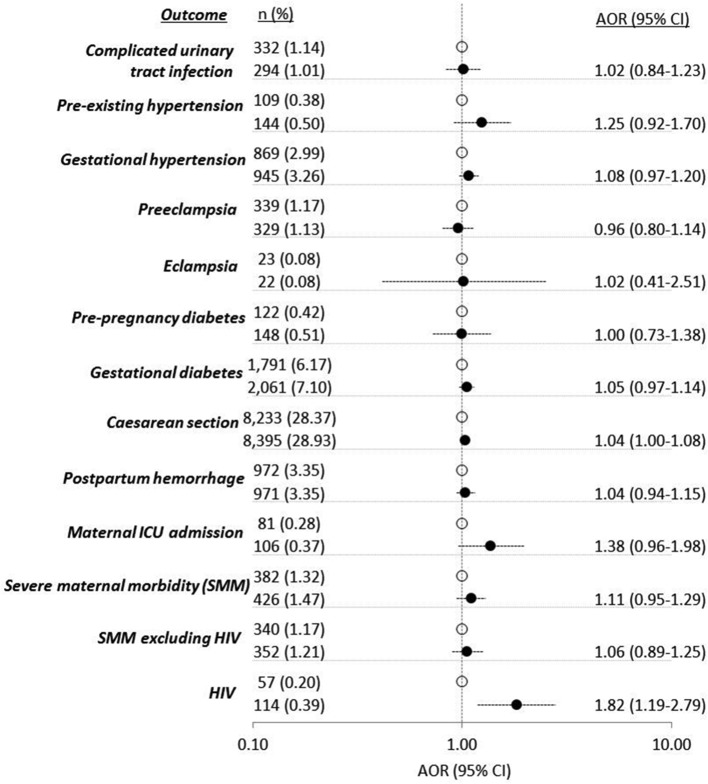

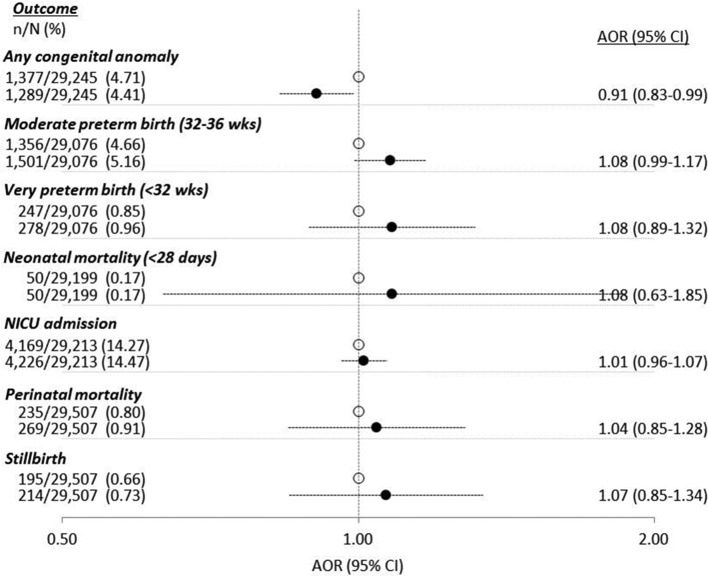

Eighty-five per cent of refugee mothers (n=29 023) were successfully matched to a non-refugee mother on COB, and year and age at arrival (±5 years). For most outcomes, differences between matched refugees and non-refugees were non-significant (see figures 1 and 2). Caesarean section (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08) and HIV (AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.79) were significantly higher among refugees. Moderate PTB approached statistical significance (AOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.17). See online supplementary table S2 for unadjusted results.

Figure 1.

Adverse maternal outcomes comparing 29 023 first births in Ontario to refugee immigrants (black circles) versus 29 023 first births in Ontario births to non-refugee immigrants (open circles), 1:1 matched on country of birth, year and age at arrival (±5 years). ORs adjusted for maternal age, parity, income quintile, official language ability, education and duration of residence. AOR, adjusted OR; ICU, intensive care unit; SMM, severe maternal morbidity.

Figure 2.

Adverse perinatal outcomes comparing first births in Ontario to refugee immigrants (black circles) versus first births in Ontario to non-refugee immigrants (open circles), 1:1 matched on country of birth, year and age at arrival (±5 years). Denominators vary with the outcome examined. ORs adjusted for maternal age, parity, income quintile, official language ability, education and duration of residence. AOR, adjusted OR; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Online supplementary figures (S1a/b through S5a/5b) disaggregate results according to the top five refugee-source countries to Ontario—Sri Lanka, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq and China. Afghan and Iraqi refugees had higher odds of caesarean section. Refugee mothers from all countries either had significantly greater odds of GDM (Afghanistan AOR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.54) or borderline greater odds of GDM (Sri Lanka AOR 1.09, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.21; Somalia AOR 1.20, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.48; Iraq AOR 1.22, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.50; China AOR 1.16, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.37) compared with their non-refugee counterparts.

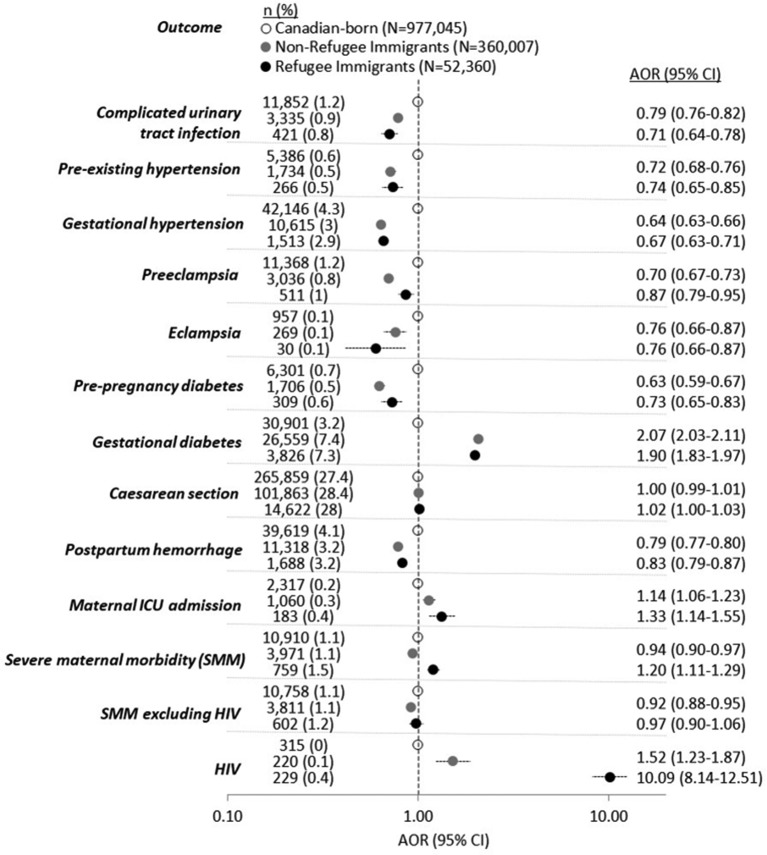

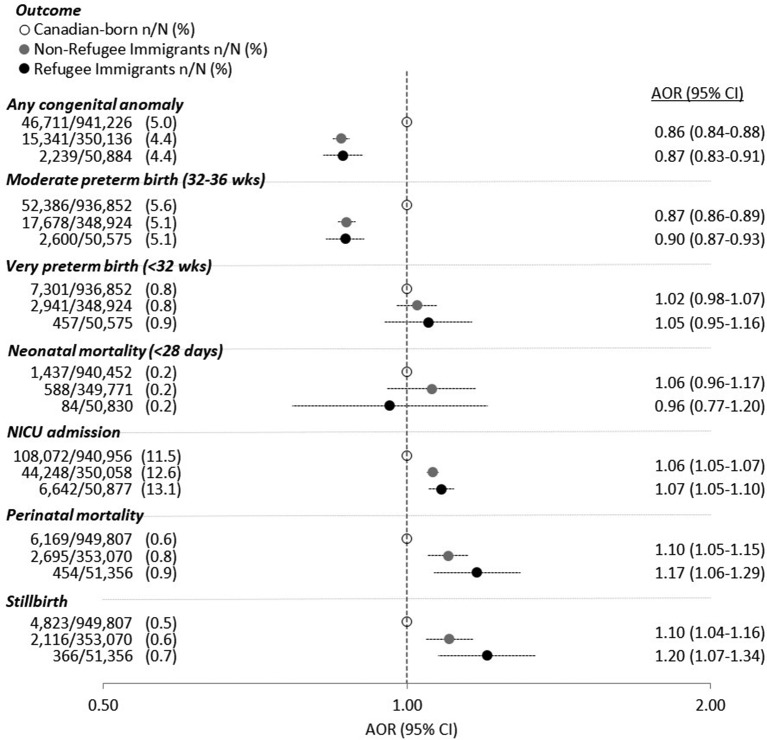

Figures 3 and 4 compare both refugees to Canadian-born mothers and non-refugee immigrants to Canadian-born mothers. Other than SMM and HIV, the two sets of AORs comparing refugees to Canadian-born mothers and non-refugees to Canadian-born mothers were in the same direction and of a similar magnitude. With respect to SMM (see figure 3), refugees had significantly higher odds compared with Canadian-born mothers while non-refugee immigrant mothers had significantly lower odds. However, after HIV was removed from the SMM index, refugees experienced similar odds of SMM to Canadian-born mothers. For other maternal outcomes (figure 3), both refugees and non-refugees compared with Canadian-born mothers had: significantly lower odds of complicated UTI, pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, prepregnancy diabetes and PPH; and significantly higher odds of caesarean section, GDM, maternal ICU admission and HIV. In terms of perinatal outcomes (figure 4), both refugees and non-refugees compared with Canadian-born mothers had: significantly lower odds of any congenital anomaly and moderate PTB; similar odds of very PTB and neonatal mortality; and significantly higher odds of NICU admission, perinatal mortality and stillbirth. See supplementary table S3 for unadjusted results.

Figure 3.

Adverse maternal outcomes comparing 52 360 births to refugee immigrants (black circles) and 360 007 births to non-refugee immigrants (grey circles) versus 977 045 births to Canadian-born (open circles) mothers. ORs adjusted for maternal age, parity and income quintile. AOR, adjusted OR; ICU, intensive care unit; SMM, severe maternal morbidity.

Figure 4.

Adverse perinatal outcomes comparing births to refugee immigrants (black circles) and births to non-refugee immigrants (grey circles) versus births to Canadian-born mothers (open circles). Denominators vary with the outcome examined. ORs adjusted for maternal age, parity and income quintile. AOR, adjusted OR; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Discussion

We found modest increased odds of caesarean section and moderate PTB among refugee compared with non-refugee mothers from the same COB. HIV was the exception with a much greater prevalence. Overall, our findings suggest that refugee status, measured with an administrative definition, is not a strong risk indicator for poor maternal and perinatal health. In addition, we found that refugee and non-refugee mothers experienced a similar magnitude of ORs for almost all outcomes when each group was separately compared with Canadian-born mothers. About one-third of outcomes were significantly worse among refugee and non-refugee immigrant mothers when compared with Canadian-born mothers.

The SMM and HIV findings are explained in detail in a previous report of ours5 (although unmatched on COB). Our current results are consistent with the previous study however with smaller HIV prevalence ratios. The smaller prevalence ratio can likely be explained by the different method used to capture HIV diagnoses (hospital discharge data in the previous study and HIV physician diagnoses data in the current study) but also because 1:1 matching of refugee to non-refugee immigrants on COB, year and age at arrival in the current study accounted for some of the difference between refugee and non-refugee immigrants. In our previous work, we found that refugee mothers with HIV did not have any greater maternal morbidity compared with non-refugee immigrant or Canadian-born mothers with HIV, suggesting that HIV during pregnancy is well managed in Ontario regardless of refugee status (with permanent residency). In contrast, a Dutch study9 describes HIV as a risk indicator for severe acute maternal morbidity among asylum seekers (refugees without permanent residency); suggesting that a lack of appropriate HIV care may be contributing to SAMM.

Refugee mothers were 4% more likely to have a caesarean section compared their non-refugee counterparts while Afghan and Iraqi refugee mothers were ~30% more likely to experience caesarean section than their same-country non-refugee counterparts. A study involving 10 Canadian hospitals31 found a significant difference between refugee, asylum-seeker and non-refugee immigrants from Southeast and Central Asia. Reasons for the higher caesarean rate among refugees were: higher parity, medical complications, low socioeconomic status, sociocultural factors and suboptimal perinatal care.31

Refugee status was also positively associated with moderate PTB and with gestational diabetes among mothers from the top five refugee-receiving countries. The relationship between refugee status and gestational diabetes may be explained by a study which found stressful events were associated with 2.5 times greater risk of gestational diabetes.32 Other research suggests maternal chronic stress is an important risk factor for PTB,33 particularly among socially disadvantaged populations.34 Previously published research of ours found that the effect of refugee status on PTB was stronger among refugee mothers who resided in a transition country prior to arriving in Canada7 with potentially greater exposure to psychosocial stress. The hypothesised physiological mechanism connecting psychosocial stress to both gestational diabetes and PTB involves dysfunction of regulatory hormones in the body—insulin resistance or impaired insulin metabolism leading to gestational diabetes32 and early release of hormones required for the initiation of labour leading to PTB.33

The extent to which refugee and non-refugee immigrants experienced the HME (relative to Canadian-born mothers) for all maternal and perinatal health outcomes was identical. We found that both refugee and non-refugee immigrants experienced higher odds of the same adverse maternal and perinatal health outcomes (one-third of all outcomes examined) compared with Canadian-born mothers. This suggests that refugee status, using an administrative definition of refugees, is not an important factor in the HME for these outcomes. These findings are also consistent with others who have stated that the HME is not evident for all health outcomes.35

Strengths and limitations

Among studies examining refugee maternal and perinatal health,5–18 36–47 our study has several unique and important strengths. First, our study used official government immigration data to identify women who met the UNHCR definition of a refugee rather than relying on COB as an indicator of refugee status, as many previous studies have done.11–18 Second, we matched refugee and non-refugee immigrant women on COB, as well as year and age at arrival (see supplementary figures S6 and S7 for unmatched results). By matching on these variables, ours is the first study to effectively address the question of whether refugee status among two otherwise similar immigrant mothers, is a risk indicator for adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Third, to our knowledge our study includes the largest sample of mothers legally classified as refugees reported in the literature contributing to adequate statistical power for our main analyses (objectives 1 and 2).

This study is not without limitations. In our main analysis, we matched 85% of refugee mothers to one non-refugee immigrant mother. To ensure that the results of the matched sample were not biased, a sensitivity analysis was conducted where the refugees and non-refugees unmatched on COB were matched instead by subregion of birth (eg, East Africa) as well as year and age at arrival. With this second round of matching, 99% of all refugee mothers were matched to a non-refugee mother either on country or subregion of birth. Analysis of this two times matched cohort yielded very similar ORs to those of the first match. Given that the results were similar, and that the first match most effectively tells us whether refugee status among immigrant mothers with a similar premigration context increases risk of adverse outcomes, we chose to present results from only the first match.

Other limitations are as follows. First, the ‘refugee experience’ as it pertains to health risks may not be consistent with the legally applied definition of ‘refugee’. Risk factors for adverse outcomes (ie, exposure to violence, forced family separation) are context dependent, such as the length of time in the migration phase and access to health and other supportive services before and during migration—factors for which we did not have data. We addressed context by matching refugees to non-refugees on COB, year and age at arrival as well as restricting analyses to the top five refugee-source countries; however, even within these COBs there is likely important heterogeneity which we could not examine or account for. A second limitation is the inability to categorise family class non-refugee immigrants according to the permanent residency status of the sponsoring family member (ie, economic or refugee). This may have caused some refugees to be misclassified as non-refugee immigrants and contributed to biassing estimates in figures 1 and 2 towards the null. However, since refugees are less likely to have the financial means necessary for sponsorship, the number of family class members who may be refugees is not likely to substantially affect estimates. A third limitation may be that estimates in figures 1 and 2 were overadjusted given that the majority of non-refugee permanent residents are selected based on their education and official language ability. However, unadjusted estimates (see supplementary table S2) demonstrate that adjusting for these variables does not substantially affect our conclusions. A fourth limitation is that we lacked data on body mass index. Finally, our findings are not generalisable to unsuccessful refugee claimants (since our study was limited to permanent residents) who may be more representative of refugees and asylum seekers in other countries.

Implications

To help understand modest differences in gestational diabetes and moderate PTB between refugee and non-refugee immigrant women, further research into stressors refugee mothers experience in their countries of origin, in transition countries and in countries of resettlement may help support development of preconception and pregnancy stress prevention and management strategies.

Research has described that refugees and other immigrants in Canada experience barriers to accessing healthcare48 had unaddressed health concerns after birth49 and experienced culturally insensitive policies.48 Indeed, such healthcare deficiencies may have contributed to the one-third of outcomes where refugee and non-refugee immigrant mothers experienced greater odds when compared with Canadian-born mothers. By the same token, it is surprising that refugee mothers did not experience an excess of maternal and infant health risks compared with non-refugee immigrants since these healthcare deficiencies are likely experienced more acutely by refugee mothers.

There are a few important caveats to our findings. First, and perhaps most importantly, the administrative definition of refugees is broad and is perhaps unable to sensitively identify refugees at highest health risk. Second, non-refugee immigrants from refugee-source countries may be just as likely to experience predeparture health risks (related to persecution) as their refugee counterparts, reducing specificity and minimising any differences between the groups. Third, all permanent resident refugees to Canada receive financial and social supports (eg, housing, resettlement), particularly in the first year after arrival as well as universal healthcare (as described in the methods section). Specialised primary healthcare centres catering to the unique health needs of refugees are available.50 51 There are also national efforts to focus on equity in the quality of care received and migrant friendly maternity care.52 These specialised health and social support efforts may be helping to minimise potential health inequities experienced by refugees. Lastly, despite official immigration policies, such as the IRPA, 200226 27 (see methods section for more details), it is possible that unofficial processes select refugees based on factors such as skill level and language fluency (ie, similar to non-refugee immigrants), effectively selecting for healthy refugees.

Future research

Refugees should be compared with non-refugee immigrants, preferably from the same COB, as this more effectively addresses the question of whether refugees, among all migrants, are at increased risk for poor health. Further refining refugee status based on detailed migration experiences would also be beneficial. Finally, to help facilitate international comparisons, refugee health researchers may find it useful to state if and how immigration policies shape the health of refugees relative to other immigrants within their borders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Contributors: SW conceived the research questions, designed the study, conducted statistical analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. RM, JGR and MLU contributed to the research design and data analysis. YS, AG, DCC, MR, JB, PD, RM, JGR and MLU contributed to data interpretation and revisions of the manuscript. MLU and JGR obtained funding. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (MOP 137110). SW is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship funded from this grant. MLU holds a Canada Research Chair in Applied Population Health. JGR holds a CIHR Chair in Reproductive, Child and Youth Health Services and Policy Research.

Disclaimer: Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and the Ethics Review Board of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data available from this study.

References

- 1. Gagnon AJ, Merry L, Robinson C. A systematic review of refugee women’s reproductive health: Refuge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Guide 6000 - convention refugees abroad and humanitarian-protected persons abroad. 2017. http://www.cic.gc.ca/English/information/applications/guides/E16000TOC.asp (accessed 1 May 2017).

- 3. Immigration, Refugees & Citizenship Canada. Facts & figures 2015: immigration overview - permanent residents – annual IRCC updates. Canada - permanent residents by province or territory and category. 2015. http://www.cic.gc.ca/opendata-donneesouvertes/data/IRCC_FFPR_17_F.xls (accessed 11 May 2017).

- 4. Settlement.org. How does Canada’s refugee system work? 2017. http://settlement.org/ontario/immigration-citizenship/refugees/basic-information-for-refugees/how-does-canada-s-refugee-system-work/ (accessed 1 May 2017).

- 5. Wanigaratne S, Cole DC, Bassil K, et al. Contribution of HIV to maternal morbidity among refugee women in Canada. Am J Public Health 2015;105:2449–56. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanigaratne S, Cole DC, Bassil K, et al. Severe neonatal morbidity among births to refugee women. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:2189–98. 10.1007/s10995-016-2047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wanigaratne S, Cole DC, Bassil K, et al. The influence of refugee status and secondary migration on preterm birth. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:622–8. 10.1136/jech-2015-206529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vigod SN, Bagadia AJ, Hussain-Shamsy N, et al. Postpartum mental health of immigrant mothers by region of origin, time since immigration, and refugee status: a population-based study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:439–47. 10.1007/s00737-017-0721-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Hanegem N, Miltenburg AS, Zwart JJ, et al. Severe acute maternal morbidity in asylum seekers: a two-year nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:1010–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Wahoush O, et al. International migration to Canada: the post-birth health of mothers and infants by immigration class. Soc Sci Med 2013;76:197–207. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vangen S, Stoltenberg C, Johansen RE, et al. Perinatal complications among ethnic Somalis in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;81:317–22. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Essén B, Hanson BS, Ostergren PO, et al. Increased perinatal mortality among sub-Saharan immigrants in a city-population in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:737–43. 10.1080/00016340009169187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belihu FB, Davey MA, Small R. Perinatal health outcomes of East African immigrant populations in Victoria, Australia: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:86 10.1186/s12884-016-0886-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bakken KS, Skjeldal OH, Stray-Pedersen B. Immigrants from conflict-zone countries: an observational comparison study of obstetric outcomes in a low-risk maternity ward in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:163 10.1186/s12884-015-0603-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller LS, Robinson JA, Cibula DA. Healthy immigrant effect: preterm births among immigrants and refugees in Syracuse, NY. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:484–93. 10.1007/s10995-015-1846-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Block A, et al. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes among women of refugee background from African countries: a retrospective, observational study in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:392 10.1186/s12884-014-0392-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gibson-Helm M, Boyle J, Cheng IH, et al. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes among women of refugee background from Asian countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;129:146–51. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibson-Helm ME, Teede HJ, Cheng IH, et al. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes comparing migrant women born in humanitarian and nonhumanitarian source countries: a retrospective, observational study. Birth 2015;42:116–24. 10.1111/birt.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Urquia ML, Gagnon AJ. Glossary: migration and health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:467–72. 10.1136/jech.2010.109405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Public Health Agency of Canada. Perinatal health indicators for Canada- 2011. 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/rhs-ssg/phi-isp-2011-eng.php

- 21. Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:135 10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joseph KS, Fahey J. Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Validation of perinatal data in the Discharge Abstract Database of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Chronic Dis Can 2009;29:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Antoniou T, Zagorski B, Loutfy MR, et al. Validation of case-finding algorithms derived from administrative data for identifying adults living with human immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS One 2011;6:e21748 10.1371/journal.pone.0021748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keung N. Tor. Star. The law says refugee claims must be heard in 60 days. So why are people waiting 16 months? 2017. https://www.thestar.com/news/immigration/2017/09/20/the-law-says-refugee-claims-must-be-heard-in-60-days-so-why-are-asylum-seekers-waiting-16-months.html (accessed 19 Nov 2017).

- 25. Keung N. Tor. Star. Canada’s refugee acceptance rate peaked in four years. 2017. https://www.thestar.com/news/immigration/2017/03/07/canadas-refugee-acceptance-rate-peaked-in-four-years.html (accessed 19 Nov 2017).

- 26. Immigration, Refugees & Citizenship Canada. Excessive demand on health and social services. 2016. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/tools/medic/admiss/excessive.asp (accessed 1 May 2017).

- 27. Minister of Justice, Canada. Immigration and Refugee Protection Act S.C. 2001, c.27. 2016. http://laws.justice.gc.ca/PDF/I-2.5.pdf (accessed 19 Dec 2016).

- 28. Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007: surveillance using routine hospitalization data and ICD-10CA codes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:837–46. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34655-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu S, Joseph KS, Bartholomew S, et al. Temporal trends and regional variations in severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:847–55. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34656-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groups 2013. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm (accessed 13 Oct 2016).

- 31. Gagnon AJ, Van Hulst A, Merry L, et al. Cesarean section rate differences by migration indicators. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287:633–9. 10.1007/s00404-012-2609-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hosler AS, Nayak SG, Radigan AM. Stressful events, smoking exposure and other maternal risk factors associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:566–74. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Latendresse G. The interaction between chronic stress and pregnancy: preterm birth from a biobehavioral perspective. J Midwifery Womens Health 2009;54:8–17. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, et al. The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol 2011;38:351–84. 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, et al. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health 2017;22:209–41. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goosen S, Hoebe CJ, Waldhober Q, et al. High HIV prevalence among asylum seekers who gave birth in the Netherlands: a nationwide study based on antenatal hiv tests. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134724 10.1371/journal.pone.0134724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dennis CL, Merry L, Stewart D, et al. Prevalence, continuation, and identification of postpartum depressive symptomatology among refugee, asylum-seeking, non-refugee immigrant, and Canadian-born women: results from a prospective cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:959–67. 10.1007/s00737-016-0633-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dennis CL, Merry L, Gagnon AJ. Postpartum depression risk factors among recent refugee, asylum-seeking, non-refugee immigrant, and Canadian-born women: results from a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:411–22. 10.1007/s00127-017-1353-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gann P, Nghiem L, Warner S. Pregnancy characteristics and outcomes of Cambodian refugees. Am J Public Health 1989;79:1251–7. 10.2105/AJPH.79.9.1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flynn PM, Foster EM, Brost BC. Indicators of acculturation related to Somali refugee women’s birth outcomes in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:224–31. 10.1007/s10903-009-9289-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kandasamy T, Cherniak R, Shah R, et al. Obstetric risks and outcomes of refugee women at a single centre in Toronto. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2014;36:296–302. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30604-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis JM, Goldenring J, McChesney M, et al. Pregnancy outcomes of Indochinese refugees, Santa Clara County, California. Am J Public Health 1982;72:742–4. 10.2105/AJPH.72.7.742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lalchandani S, MacQuillan K, Sheil O. Obstetric profiles and pregnancy outcomes of immigrant women with refugee status. Ir Med J 2001;94:79–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King PA, Duthie SJ, Li DF, et al. Obstetric outcome among Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong: an age-matched case-controlled study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1990;33:203–10. 10.1016/0020-7292(90)90002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malamitsi-Puchner A, Tzala L, Minaretzis D, et al. Preterm delivery and low birthweight among refugees in Greece. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1994;8:384–90. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1994.tb00477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuvacic I, Skrablin S, Hodzic D, et al. Possible influence of expatriation on perinatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1996;75:367–71. 10.3109/00016349609033333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu C, Urquia M, Cnattingius S, et al. Migration and preterm birth in war refugees: a Swedish cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:141–3. 10.1007/s10654-013-9877-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stewart M, Dennis CL, Kariwo M, et al. Challenges faced by refugee new parents from Africa in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2015;17:1146–56. 10.1007/s10903-014-0062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Platt RW, et al. Refugee and refugee-claimant women and infants post-birth: migration histories as a predictor of Canadian health system response to needs. Can J Public Health Rev Can Sante Publique 2007;98:287–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Women’s College Hospital. Crossroads clinic. http://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/programs-and-services/crossroads-clinic/ (accessed 21 Jul 2017).

- 51. Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services. http://accessalliance.ca/ (accessed 21 Jul 2017).

- 52. Gagnon AJ, DeBruyn R, Essén B, et al. Development of the Migrant Friendly Maternity Care Questionnaire (MFMCQ) for migrants to Western societies: an international Delphi consensus process. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:200 10.1186/1471-2393-14-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018979supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)