Abstract

Objectives

Suicides by train have devastating consequences for families, the rail industry, staff dealing with the aftermath of such incidents and potential witnesses. To reduce suicides and suicide attempts by rail, it is important to learn how safe interventions can be made. However, very little is known about how to identify someone who may be about to make a suicide attempt at a railway location (including underground/subways). The current research employed a novel way of understanding what behaviours might immediately precede a suicide or suicide attempt at these locations.

Design and methods

A qualitative thematic approach was used for three parallel studies. Data were gathered from several sources, including interviews with individuals who survived a rail suicide attempt (n=9), CCTV footage of individuals who died by rail suicide (n=16) and qualitative survey data providing views from rail staff (n=79).

Results

Our research suggests that there are several behaviours that people may carry out before a suicide or suicide attempt at a rail location, including station hopping and platform switching, limiting contact with others, positioning themselves at the end of the track where the train/tube approaches, allowing trains to pass by and carrying out repetitive behaviours.

Conclusions

There are several behaviours that may be identifiable in the moments leading up to a suicide or suicide attempt on the railways which may present opportunities for intervention. These findings have implications for several stakeholders, including rail providers, transport police and other organisations focused on suicide prevention.

Keywords: mental health, qualitative research, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

By mapping together three data sources, this study took a novel approach to understanding what behaviours might precede a suicide or suicide attempt at a railway location, thus consequently provides a more complete picture of what behaviours might precede a suicide or suicide attempt at a railway/subway location.

There are some distinct similarities, and ‘triangulation’, in the findings of the three studies reported which strengthen their conclusions.

Due to difficulties with accessing this type of data, our sample sizes are limited, therefore findings are unlikely to be generalisable across all railway and underground locations.

Introduction

Suicides on the railway and underground network in the UK are of great concern to the railway industry, putting a financial strain on the service, as well as emotional strain on their staff, including British Transport Police (BTP) officers.1 Between 2015 and 2016, 278 people died by suicide or suspected suicide on UK railways and undergrounds,2 with over 1100 interventions taking place to prevent a suicide.3 The UK rail industry have their own suicide-prevention strategy, and work closely with organisations such as the Samaritansi and BTP to understand and prevent suicides.4 Researchers have tried to understand who might be at risk of suicide on the railways, and what environmental factors might play a role in suicides on the railways. Being male, living close to a railway and having a diagnosed psychiatric illness have all been established to increase the risk.5 The time of year and time of day have also been linked to suicide risk.5

Individuals’ behaviours immediately preceding a suicide attempt are a crucial element of the suicidal process, that is, the multidimensional sequence of events by which suicidal ideas become plans, and plans are then acted upon.6 Understanding behaviour before an attempt on the railways is thus a key aspect of understanding why and how individuals attempt suicide using this method. Yet there is very little research into this,5 and existing research tends to focus on the perspectives of witnesses and staff present at the time of the suicide. For example, research that has gathered the views of police officers suggests that behaviours associated with subsequent suicide attempts include leaving behind belongings, avoiding eye contact, erratic movements, erratic communication and confusion. Other behaviours include being under the influence of alcohol, wandering around and unusual clothing.7 This type of research tells us about some of the potential behaviours that may precede a railway suicide, however it relies on interpretation by a third party and may be subject to memory bias. In this context, the accounts of individuals who have survived an attempt on the rails can offer some important insights and help triangulate the findings of research focusing on staff/witnesses, but are also subject to poor recall.

Structured analyses of close circuit television (CCTV) data can usefully complement witness and survivor accounts of the events, decisions and behaviours leading up to a suicidal attempt on the rails, particularly the moments immediately preceding the act. In addition, this method may lead to identifying discernible circumstances and patterns of behaviour in the lead up to an incident which may assist staff in preventing suicide on the railways. This information could feed directly into staff training and inform new initiatives to reduce suicide on the railways, including computer software capable of detecting ‘high risk’ behaviour from live CCTV data. However, there have been few previous attempts to use rail suicide CCTV data for these purposes,5 8 and their primary focus has been limited to identifying how suicidal individuals position themselves on the tracks.9 10 Only one publication that focused on Canadian railway locations has used CCTV data to establish possible identifiable behaviour in the moments preceding a suicide.8 There are no publications which incorporate an analysis of CCTV data of people who have died by rail suicide with first-hand accounts of suicidal behaviour at railway locations, from the perspectives of those who have survived and/or have witnessed such behaviour at railway locations.

The aim of the current study was to identify behaviours that may precede a suicide or suicide attempt on the railway or underground using multiple data sources: CCTV footage of rail suicides, interviews with individuals who have attempted suicide on the railway and accounts from staff working in railway settings.

Methods

Design

Three parallel studies were carried out to understand what behaviours may precede a suicide or suicide attempt, using multiple perspectives (ie, CCTV, interviews with survivors and comments from staff working in rail locations). This work forms part of a wider study into why people choose to end their lives on the railways (see The QUEST study, http://questcoding.wikispaces.com/). Railways included both rail and underground networks across the UK. Written informed consent was provided by all participants for both the survey study and interviews. Consent for CCTV analysis was gained through BTP.

CCTV study

We carried out a structured analysis of CCTV data of individuals (13 males and 3 females) who took their lives on the rails in 2013. BTP provided 16 clips of fatal attempts at railway stations (n=3) and underground stations (n=13). In relation to each incident, the footage includes all or editedii CCTV data—from the moment the person came to the train or tube station (or when they first appear on CCTV) up to the moment of death (this ranged between 2 min and 12 hours, with the average footage lasting 30 min).

Analysis: Analysis of these CCTV data involved coding and making detailed notes for every 2 min segments of footage.11 The initial coding scheme was developed using an iterative coding process, based on emerging interview and survey findings, and existing evidence; and was refined as the study progressed. Our aim was to analyse people’s behaviour before taking their lives on the railways. To ensure interobserver reliability, the initial coding was conducted by one author (J-MM) and checked for consistency by a second author (JB), both are experienced qualitative researchers who specialise in suicide. The final coding scheme was agreed by three authors (J-MM, LM, JB) (see table 1).

Table 1.

Close circuit television coding scheme

| Code number | Code |

| Code 1 | Position of the person on the platform. |

| Code 2 | Were other people/potential bystanders present? |

| Code 3 | Did the person interact with others? |

| Code 4 | Behaviour/body language. |

| Code 5 | How many trains went by in both directions before each incident? |

| Code 6 | Comparison with other passengers’ behaviour. |

| Code 7 | Do other passengers appear to notice anything suspicious? |

Interviews

Interviews were carried out as part of a wider study into why people consider or attempt to end their lives on the railways (The QUEST study). Participants for the current research included nine UK nationals (six males and three females) who spoke about their behaviour preceding a suicide attempt at a railway or underground location. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 72 years, with most describing themselves as white British and one British Indian. Participants were recruited through an online survey and via the BTP. Depending on the preference and location of the participant, interviews were conducted either face-to-face in university premises or in a private room at a local Samaritans’ branch or over the telephone. Interviews were conducted by J-MM or JB.

A semistructured interview schedule was used to explore participants’ experiences of attempting suicide on the railways, and for the current study focus was given to behaviours immediately preceding an attempt/planned attempt when at a station.

Analysis: Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and then analysed for both semantic and latent themes using an inductive thematic approach.12 13 Identifiable information was removed to ensure participant anonymity. Transcripts were read at least twice, summarised and major themes recorded. Data coding was iterative: a coding frame was developed based on analysis of the first interview transcript and then refined based on subsequent transcripts, until themes were finalised. NVivo V.10 was used in the final stages of coding to assist with this process. Coding and final themes were checked for consistency by two authors (JB and J-MM). No participants were previously known to either of the coders.

Online staff survey

The aim of this survey was to gain a better understanding of railway suicidal behaviour from a front-line perspective, using both structured and open-ended questions. The 39-item survey (see online supplementary file) covered several key areas, including demographics, relevant training, views and experiences of suicidal behaviour on the railways, and suggestions for prevention. The current research focused on drawing out what behaviours staff reported as potentially preceding a suicide or suicide attempt on the rails.

bmjopen-2017-021076supp001.pdf (253.6KB, pdf)

The survey was piloted with a small number of Network Rail staff, after which purposive sampling was used to recruit respondents via the railway’s intranet. A link to the questionnaire was sent, along with a briefing document, to specific points of contact within the rail industry through the suicide prevention duty holders group, who then shared the link with their respective organisations. The target population included employees in all roles, in all railway environments across the country, including transport police. No employees were excluded from the study but briefings focused on front-line operational staff as they are more often involved either directly or indirectly with suicide incidents.

Responses were received from 140 (103 males, 35 females, 2 unknown) staff aged 18–64 years, from a wide range of disciplines within the railway industry, with experience ranging from 2 to 39 years. A total of 79 participants responded within the 3-month time frame set for data collection and were therefore included in the full analysis of the study. The additional 61 responses received outside of the data-collection period were scanned for additional themes but were suggestive of data saturation and therefore the full analysis focused on the initial 79 responses. Of these, 26 had direct experience of dealing with suicidal behaviour (including fatal attempts) on the rails.

Analysis: A qualitative design was used to collect complex textual descriptions and allow for explanations of the themes found in the data to support the discovery of ‘norms’14 that seek to understand how railway employees experience railway suicides. Responses were analysed thematically12 with a focus on semantic codes. Both open and axial coding techniques were used. The content and context of the text were analysed, and the identified codes were collated into themes. These themes were reviewed, integrated where necessary and refined to produce clear definitions on which to base the final themes.12 All coding was carried out by one author (EH) and checked for consistency by a second author (IN) who is experienced in qualitative research. No participants were previously known to the coders.

Results

Five main themes were derived from the analysis of CCTV footage: ‘station hopping and platform switching’, ‘limited contact with people’, ‘allowing train to pass by’, ‘position when jumping/getting onto the tracks’ and ‘repetitive behaviours’. Each is discussed below with comments from participants who survived a suicide attempt on the railways and from staff who completed the online survey. A sixth theme, ‘trying to look normal’, emerged from the interview data and is discussed with reference to the CCTV analysis and staff comments.

Station hopping and platform switching

Five of the 16 clips we analysed (two clips did not provide sufficient footage) showed people who travelled between two or more stations before their suicide. An additional two clips showed individuals leaving the station building and then returning to the same station. Some individuals (n=3) moved between platforms at the same location. Several reasons could explain this behaviour, including that these individuals might be looking for a quiet location, going to a specific location or preparing themselves mentally to end their lives. It is difficult to fully understand the state of mind of individuals who move between platforms and/or stations, however two interview participants mentioned their reasoning/thoughts when carrying out these behaviours:

I walked for a while and I walked around X [station] first because I’d wondered about jumping there and then I ended up at Y [nearby station], I don’t know why, I just did. But a few hours of trying to think and not being able to think, wandering round stations, on and off platforms, in between barriers, just really quite stressed and confused. (Interviewee A6)

And then I was… I got worried that they might be watching on CCTV… So I got on a train and I got off at X [station] … And then I repeated the process there. (Interviewee A8)

There was no mention of station hopping or platform switching in the staff survey data, indicating that respondents may not have been aware that this behaviour can potentially precede a suicide or suicide attempt.

Limited contact with people

The majority of individuals in the CCTV footage positioned themselves away from others. Only one clip showed an individual interacting with a member of the public, having instigated contact with another passenger. Most individuals in the clips looked down at the ground and away from other people. Eleven clips showed that other people were present when the person jumped/got on the tracks. One clip showed no one else being present, and three clips did not provide enough visibility to judge.

Two interview participants mentioned trying to avoid being seen by other people when they were about to attempt suicide to avoid an intervention:

“I didn’t want other people around to see and I thought there was no-one else on the platform but someone came through.” And “… timing of the day. I’d looked around, I’d looked up the escalators, I’d looked in the corridor, I hadn’t been able to see anyone – I don’t know where they came from, I didn’t see them on the platform – but I’d looked around, I’d waited, I’d left the platform when there were people there, I’d come back. I thought I’d looked to see if there was CCTV as well and I hadn’t seen any so yeah.” (Interviewee A6)

I was like waiting for like people to be off the platform before I did anything. And I was also kind of worried that people like who saw me were like, ‘He looks a bit weird’, so I’m going to stay down here. So there was no one near me. (Interviewee A8)

In contrast, findings from the staff survey indicate that some people may approach staff. Staff were asked if they had ever spoken to a suicidal person on or near a station. All but one of the 79 participants responded: 67% (n=52) had indirect experience of dealing with suicide on the rails and 33% (n=26) reported having had direct contact with a suicidal person, in some cases having been approached by a suicidal individual:

Many have approached me. They have told me they don’t feel right or that they are feeling like they want to do something stupid, or just they want to kill themselves (BTP officer, 11–15 years in job)

Position when jumping/getting onto tracks

In the 16 clips we analysed, 14 people jumped/got onto the tracks at the end of the platform where the train approaches. Two individuals jumped/got onto the tracks at the non-approaching end. No individuals jumped/got onto the tracks from the middle of the platform. Several people positioned themselves at the approaching end of the platform very close to barriers and waited for the train to arrive, whereas some individuals moved back and forth along the platform, moving to the approaching end when the train arrived.

Three interview participants mentioned their position on the platform. These participants reported that they had chosen a particular station/tube station because they could get close to the approaching end and near to the ‘tunnel’ opening. One participant felt that getting close to the tunnel would reduce the likelihood that the driver would spot him (and brake):

…There’s a way back down towards the tunnel, and I assumed that would be an easier place to jump across without the train driver seeing me. (Interviewee A5)

It was one of those platforms that goes right up to the tunnel – I’d chosen it specifically for that reason. (Interviewee A6)

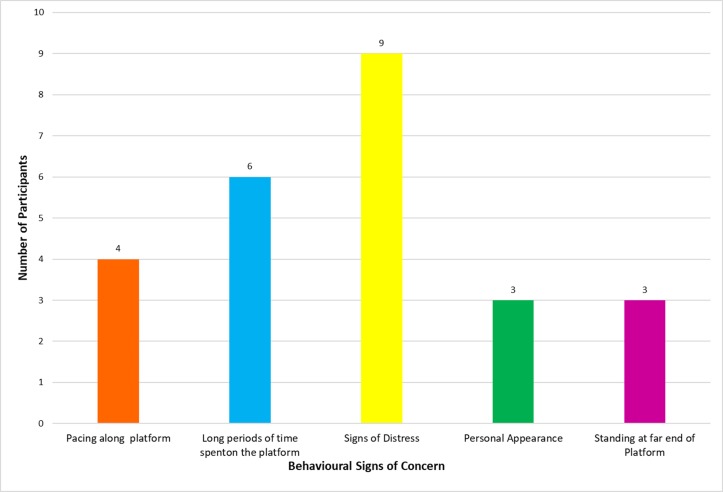

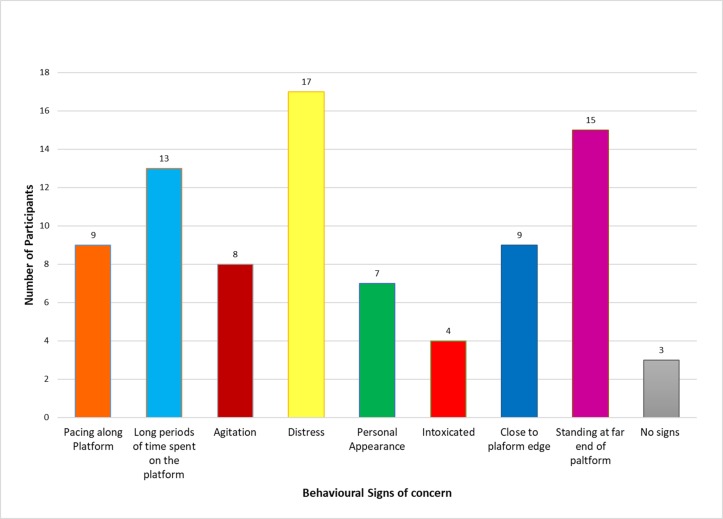

Staff (14%, n=18) also identified individuals being positioned towards the approaching end of the tunnel as a warning sign (see figures 1 and 2). Twelve staff respondents also mentioned that individuals would stand close to the platform edge:

Figure 1.

Behaviours and warning signs identified by staff with direct experience of rail suicide prior to an incident.

Figure 2.

Behavioural antecedents and warning signs identified by staff with indirect experience of railway suicide.

I noticed a lady once at (*****) station standing very close to the edge. The behaviour seemed very strange as she took her coat off and folded it up then put her handbag down, then stood near the edge of the platform. I asked the lady if she was ok and mentioned that she should stand behind the yellow line, after this she just put her coat back on and left the station (Role redacted to protect anonymity, 15+ years in job)

Allowing trains to pass by

Eight clips showed individuals allowing trains to pass by (three clips did not show sufficient footage, four clips showed no trains passing on the same platform). The individuals in these clips often spent a substantial amount of time at the platforms in comparison with those who jumped/got onto the tracks in front of the first train that arrived (n=5). Several reasons could be suggested for this behaviour, such as mentally preparing oneself to end one’s life or waiting for the platform to be less crowded. Significantly, this behaviour means that people spend more time on the platform and can increase the time for an intervention to occur.

Two interview participants mentioned their reasoning for allowing trains to pass by, which suggests they waited for the platform to be less crowded and/or they were working up the courage to jump/get onto the tracks:

“But yeah and then I went down to the Underground and didn’t get on a train at all but I did walk between a few of the difficult platforms and lines so yeah I had no intention of getting on a train.” And “Late evening so I’d waited till after rush hour and I’d gone down and I just spent so long trying to find a time when there was definitely no young people, like somehow children I definitely couldn’t do it if there was any kids anywhere. And then all these people going back from work I felt really guilty they were going to be late and they weren’t going to see their families or people would be disrupted. It was such a big thing, and then I was trying to wait until it was quiet and there was no-one around.” (Interviewee A6)

“I kept like waiting for like a platform to be completely empty. Because I didn’t want anyone to see me.” And “Because I couldn’t do… I don’t know what it was. And I remember… I had spent about 15 min at X [station]. Maybe a little more. Kind of like willing myself to do it.” (Interviewee A8)

Staff (15%, n=19) also reported that waiting for long periods of time at the platform/station could be a potential indicator that someone is going to make a suicide attempt.

Repetitive behaviour

Those individuals in the footage that did not jump/get onto the tracks immediately once entering the station (n=11) carried out a number of repetitive behaviours. Some of these could be considered ‘normal’ such as pacing/fidgeting, and therefore unlikely to be noticed by other people as ‘abnormal’. However, these individuals also carried out several repetitive behaviours which could be noticeable by station staff or other people if the person was observed. These behaviours included station hopping, switching platforms, walking up to the platform edge then returning to the wall/seating area, walking up and down the platform, walking up and down stairs/escalators. One interview participant mentioned his repetitive behaviour being significant:

“I’d gone into town specifically to step in front of a train… I kept going back and forth between like a bench and the edge of the platform.” And “There’s always going to be some kind of warning sign… For example, like, to go with my experience, I was sitting at the point where the trains come in, like, the edge of the tunnel. And I was on that spot for about… upwards of 15 min. Like going, sitting on a bench, and then like when I could hear the train coming I would go to the edge of the platform… And then when I couldn’t do it, I’d go back to the bench.” (Interviewee A8)

Ten staff respondents (10%) identified pacing behaviour as being a cause for concern, and others (13%, n=17) noted that signs of agitation and distress can also be a warning sign.

Trying to look normal

Two interview participants reported having tried to blend in and ‘look normal’ at the time of their attempt. This could potentially explain some of the behaviour identified in the CCTV data, such as people who were looking at their phones and an individual who picked up a paper and seemed to be reading it just before jumping:

I was trying to look normal and look like I had some purpose.’(Interviewee A6)

I was wearing my earphones… To kind of like… no one’s going to bother me because I’m listening to my music. (Interviewee A8)

In contrast, staff felt that individuals who were about to make an attempt would show clear signs of distress or of ‘behaving in an odd manner’, even when ‘being quiet so as to not draw attention to themselves’. Indeed, a visibly distressed and ‘unusual’ appearance was the behavioural sign most often identified as concerning by staff participants, including both those who had direct and indirect experience of working with suicidal individuals (see figures 1 and 2). Many described this as a markedly ‘withdrawn’, ‘zoned out’ appearance, seemingly ‘devoid of emotion’ and ‘disinterested in surroundings’. ‘Staring at the track’ and ‘staring into space’ were both mentioned under this category, as were ‘sitting with their heads down’ or ‘in their hands’ and ‘looking lost’, ‘in their own world’ with ‘a sunken inward look of lost hope’. Others discussed having (also) witnessed a more ‘outward’ pattern of ‘panicked’, ‘agitated’ and ‘erratic behaviour’, including ‘throwing belongings across the station’ and having ‘incoherent conversations’, and a ‘dishevelled’, ‘drunk’ appearance.

While these responses suggest that individuals may not always seek or succeed to ‘look normal’ before a suicide attempt, some staff also commented on the difficult task of identifying potentially suicidal individuals as there are, at times, no warning signs:

Suicidal people don’t really stand out until they make a move for a jump or go onto the track, suicidal persons come in all shapes and sizes and socioeconomic backgrounds, there is no stereotypical sign attributable (Mobile Operations Manager, 6–10 years in job)

Very rare to find someone as they tend to hide in out the way places. If a cry for help, the person will normally be spotted at the end of a platform or around a public footpath crossing, hanging around alone. A very difficult question to answer as it is actually rare to find someone in that state. Those I have encountered have been distressed and just look ‘alone’ with no purpose other than lost in their own thoughts’ (Mobile Operations Manager, 15+ years in job)

Discussion

Previous research has identified behaviours that may precede a rail suicide attempt such as erratic movements and leaving belongings behind,5 7 8 however much of this research has focused on the perspectives of witnesses to these events, whose memories may be subject to memory bias. The current research has for the first time brought together CCTV data of people who have died by suicide on the railways, data from individuals who have attempted suicide by rail and data from front-line staff who deal with suicides at railway/tube locations.

Our findings suggest that it can be difficult to detect those who may be about to end their lives at stations, yet some forms of repetitive behaviour which appear outside of ‘normal’ commuting behaviour have the potential to signify that someone may be a risk of suicide. Five of the 16 individuals whose footage we analysed jumped in front of the first train to arrive on the platform (though in all cases but one there was a delay between their arrival on the platform and the first train going past). However, other individuals in the footage showed distinctive behaviours that would not be normally expected in commuters, such as moving between platforms, station hopping and waiting at the station for a significant amount of time while allowing trains to pass by. These behaviours were also commented on by those who had survived a rail suicide attempt and staff. In turn, this has two important implications: (1) station hopping means that these individuals spend a longer time in the railway/underground system, therefore increasing the chance of an intervention; (2) platform switching could be a noticeable behaviour that falls outside of ‘normal’ commuting behaviour, again increasing the opportunity for intervention. Although it should be noted that these behaviours will not always predict that a person is preparing to end his/her life, but may act as an indicator to trained staff.

Together our interview, survey and CCTV data suggest that a visible presence of staff or other potential sources of support (including lay volunteers) may reduce the likelihood of an attempt being made. Additionally, the likelihood of intervention may be even greater if staff, including those monitoring CCTV, have heightened awareness of the time people spend on platforms, and if staff and other bystanders (including commuters) are aware of how to potentially spot and assist someone in distress. Staff reports of being approached by suicidal individuals suggest that having a presence at stations could also encourage suicidal individuals to seek help. Furthermore, the use of intelligent technology for identifying behavioural algorithms15 could be adapted to identify suicidal behaviours but rigorous testing would be necessary to ensure that this was neither oversensitive nor undersensitive to these types of behaviours.

Limitations

The current research must be considered within its limitations. It is important to note that the CCTV included is a small sample of station incidents chosen by BTP which will not necessarily reflect every person’s behaviour in this situation, and may not be generalisable to behaviour in other railway locations such as tracks, bridges or level crossings. A more in-depth analysis of CCTV footage would need to be carried out, ideally with a focus on locations that are known to be ‘high risk’ or in more rural locations. In addition, the clips we analysed are limited to footage of those who died by suicide. Analysing footage of ‘life-saving interventions’ by a member of the public (potentially in comparison with CCTV data of both suicide/attempted suicide and of ‘normal’/incident-free platform behaviour) may provide important learning on the role of bystanders—and potential bystander interventions—in rail suicide prevention.

The staff survey and interview study were also based on small samples, and as such not generalisable. In addition, both are subject to the potential biases and other methodological limitations common to self-report data. Nonetheless, there are some distinct similarities, and ‘triangulation’, in the findings of the three studies reported which strengthen their conclusions.

Conclusion

Identification of behaviour that precedes a rail suicide or suicide attempt can be difficult, but potentially very useful to inform suicide-prevention efforts in these settings. Using a multimethodological approach, we identified a range of behaviours and other potential warning signs immediately preceding suicidal behaviour on the rails. This includes behaviours which could be easily dismissed as ‘normal’ commuting behaviour (such as pacing up and down a station platform or fidgeting) but also behaviours such as station hopping, platform switching and spending a long time at specific locations which arguably fall outside of ‘normal’ commuting behaviour. Our findings, although based on small samples, suggest that these behaviours are largely repetitive and could present important opportunities for identification and intervention in locations where platform screen doors are not or cannot be put in place.16 The findings from this research (and from the Quest study) have been used in the development of a national campaign by the railways called ‘small talk saves lives’. The campaign aims to encourage commuters to engage in conversation with people who appear visibly distressed at railway locations, in order to interrupt the suicidal thought process and ultimately prevent suicides.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

A UK-based suicide-prevention charity.

Some data were shortened by the British Transport Police if the footage was over 1 hour. Where station hopping occurred, clips from stations were added together. No footage of individuals actually travelling on the railways/tubes was available.

Contributors: Study design was carried out by all authors. Recruitment for interviews was carried out by JB, BF, IK, J-MM and LM (ie, via an online survey). Recruitment for the staff survey was carried out by EH and IN. J-MM and JB conducted and analysed the interviews. J-MM analysed the CCTV data which was checked and second coded by JB. Staff survey data were collected and analysed by EH and checked for consistency by IN. The article was written by J-MM with contributions from all other authors.

Funding: This study was commissioned by the Samaritans and funded by Network Rail.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The research ethics committees at Middlesex, Westminster and King’s College London Universities granted ethical approval for this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Our Results section of this manuscript provides illustrative examples of our data which have been anonymised. Due to the qualitative nature of this study, we cannot make full transcripts, footage or survey data available as these could potential identify our participants.

References

- 1. Rail Safety and Standards Board. Improving suicide prevention measures on the rail network in Great Britain. 2014.

- 2. Office of Rail and Road. Rail Safety Statistics, 2015-16 Annual Statistical Release. UK: Office of National Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rail Safety and Standards Board. A reference guide to safety trends on GB railways: annual safety performance report 2015/16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Network Rail. Suicide Prevention on the Railway.. 2016.

- 5. Mishara BL, Bardon C. Systematic review of research on railway and urban transit system suicides. J Affect Disord 2016;193:215–26. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Runeson BS, Beskow J, Waern M. The suicidal process in suicides among young people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:35–42. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lukaschek K, Baumert J, Ladwig KH. Behaviour patterns preceding a railway suicide: explorative study of German Federal Police officers' experiences. BMC Public Health 2011;11:620 10.1186/1471-2458-11-620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mishara BL, Bardon C, Dupont S. Can CCTV identify people in public transit stations who are at risk of attempting suicide? An analysis of CCTV video recordings of attempters and a comparative investigation. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1245 10.1186/s12889-016-3888-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rådbo H, Svedung I, Andersson R. Suicides and other fatalities from train-person collisions on Swedish railroads: a descriptive epidemiologic analysis as a basis for systems-oriented prevention. J Safety Res 2005;36:423–8. 10.1016/j.jsr.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dinkel A, Baumert J, Erazo N, et al. . Jumping, lying, wandering: analysis of suicidal behaviour patterns in 1,004 suicidal acts on the German railway net. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:121–5. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heath C, Hindmarsh J, Luff P. Video in qualitative research. USA: Sage Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. Hampshire: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thorne S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs 2000;3:68–70. 10.1136/ebn.3.3.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang X. Intelligent multi-camera video surveillance: a review. Pattern Recognit Lett 2013;34:3–19. 10.1016/j.patrec.2012.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rådbo H, Svedung I, Andersson R. Suicide prevention in railway systems: application of a barrier approach. Saf Sci 2008;46:729–37. 10.1016/j.ssci.2006.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021076supp001.pdf (253.6KB, pdf)