Abstract

Objectives

The prevalence of obesity among populations in the Atlantic provinces is the highest in Canada. Some studies suggest that adequate fruit and vegetable consumption may help body weight management. We assessed the associations between fruit and vegetable intake with body adiposity among individuals who participated in the baseline survey of the Atlantic Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (Atlantic PATH) cohort study.

Methods

We carried out a cross-sectional analysis among 26 340 individuals (7979 men and 18 361 women) aged 35–69 years who were recruited in the baseline survey of the Atlantic PATH study. Data on fruit and vegetable intake, sociodemographic and behavioural factors, chronic disease, anthropometric measurements and body composition were included in the analysis.

Results

In the multivariable regression analyses, 1 SD increment of total fruit and vegetable intake was inversely associated with body mass index (−0.12 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.19 to –0.05), waist circumference (−0.40 cm; 95% CI −0.58 to –0.23), percentage fat mass (−0.30%; 95% CI −0.44 to –0.17) and fat mass index (−0.14 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.19 to –0.08). Fruit intake, but not vegetable intake, was consistently inversely associated with anthropometric indices, fat mass, obesity and abdominal obesity.

Conclusions

Fruit and vegetable consumption was inversely associated with body adiposity among the participant population in Atlantic Canada. This association was primarily attributable to fruit intake. Longitudinal studies and randomised trials are warranted to confirm these observations and investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data from a large-scale population-based survey with objectively measured body composition.

Associations between fruit and vegetable intake with body adiposity measurements were assessed in combination and separately using multivariable regression models.

Limitations of a cross-sectional analysis with an unrepresentative sample.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of obesity, a major risk factor for a variety of chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus and some cancers, is a critical worldwide public health concern.1 People living in Atlantic Canada have the highest prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2) among the Canadian population. In 2011, the prevalence of obesity ranged from 24% in Prince Edward Island to 28% in Newfoundland and Labrador. It is predicted that the percentage of people who are overweight or obese will continue to increase.2 Appropriate strategies to effectively halt the obesity epidemic among populations in this region (and other areas) are of critical public health interest.

Fruits and vegetables are important components of a healthy diet, contributing to a large proportion of an individual’s daily intake of vitamins, minerals and dietary fibre. Health Canada recommends that adults should consume 7–10 servings of a variety of fruits and vegetables per day to reduce the risks of cancer and other chronic diseases.3 Further, substantial evidence has shown that increased consumption of fruits and vegetables may reduce the risks of mortality from all causes4 and the development of cardiometabolic disease.5–8 Interestingly, some systematic reviews have suggested that appropriately increased fruit and vegetable intake may help body weight management by preventing the development of obesity and reducing body weight over time.9–12 However, one meta-analysis of interventional trials showed that increased fruit and vegetable intake had an effect on weight loss11; another study did not find an effect in terms of body weight reduction.13 A Canadian study found that increased fruit intake was associated with reduced weight gain over a 6-year period among participants of the Quebec Family Study.14 Additionally, some studies suggest that fruit consumption might have a more favourable impact on body weight control than vegetable consumption.9 15

We hypothesise that fruit and vegetable consumption may play a role in the obesity epidemic among populations living in Atlantic Canada. The primary aims of this study were to assess: (1) the intake of fruits, vegetables and 100% fruit or vegetable juice and (2) associations between fruit, vegetable and 100% fruit or vegetable juice intake with anthropometric indices and body composition among participants who were enrolled in the baseline survey of the Atlantic Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (Atlantic PATH) study. We further assessed how the consumption of fruit, vegetable and 100% fruit or vegetable juice were associated with body adiposity measurements by considering these three components as one food group and treating them independently in the multivariable logistic regression analyses.15 16

Methods

Study population

The Atlantic PATH study is a part of the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project, a pan-Canadian longitudinal cohort study examining the role of genetic, environmental, behavioural and lifestyle factors in the development of cancer and chronic disease.17 18 The Atlantic PATH study is a population-based cohort in which study participants were residents of one of the four Atlantic Canadian Provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island) and aged between 35 and 69 years. Study participants were recruited from the general public through a combination of community outreach and awareness activities, advertising and media campaigns, and invitation. During 2009–2015, 31 173 Atlantic PATH study participants, including 9445 men and 21 728 women, were recruited from the four Atlantic Canada provinces. The study was approved by appropriate Research Ethics Boards in each province. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. All data collection procedures followed the research protocol guidelines as approved by the Research Ethics Boards.

We excluded 4833 participants from this analysis as a result of current pregnancy (n=40), missing data on fruit, vegetable and 100% fruit or vegetable juice (n=816), anthropometric indices (n=4127), and other variables (n=90). The final analysis sample was composed of 26 340 participants (7979 men and 18 361 women).

Data collection

Data collection procedures have been reported previously.18 19 In brief, a set of standardised questionnaires on sociodemographic, health status, medication use, diet, lifestyle factors and self-measured anthropometric indices were completed by participants. Physical measurements (including anthropometric indices and body composition) were measured by research nurses at an assessment centre.

Assessment of fruit and vegetable consumption

Consumption of fruit, vegetable and 100% fruit or vegetable juice were assessed by using three questions: (1) In a typical day, how many servings of vegetable do you eat? One serving is about ½ cup or 125 mL of fresh, frozen, canned or cooked vegetables. (2) In a typical day, how many servings of fruit do you eat? One serving is about ½ cup or 125 mL of fresh, frozen or canned fruit. (3) In a typical day, how many servings of 100% fruit or vegetable juice do you drink? One serving is about ½ cup or 125 mL.

Assessment of sociodemographic and behavioural factors

Ethnicity was categorised as white and non-white because there was little ethnic diversity in the cohort. Educational attainment was categorised as high school or lower, college level and university level or higher. Marital status was grouped as married or living together and single, divorced, separated or widowed. For smoking behaviour, participants were grouped as non-smoker, former smoker and current smoker. For alcohol drinking, respondents were classified as abstainer, occasional drinker (>0 to ≤2–3 times/month), regular drinker (≥1 time/week to ≤2–3 times/week) and habitual drinker (≥4–5 times/week).19

Physical activity was assessed by using either the long or short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).20 For the evaluation of total physical activity, we calculated metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-min/week) for each participant with data derived from the long and short form questionnaires, respectively. The MET scores were computed according to the IPAQ scoring protocol.21 We then ranked the sex-specific total MET scores into tertiles for data derived from the long and short form questionnaires, separately. Levels of total physical activity were classified as low, medium and high by the low to high MET score tertiles.

Assessment of chronic diseases

Self-reported current medication use was collected and medication data were coded according to the Nova Scotia Formulary (NSF) (www.nspharmacare.ca).22 The NSF uses the standardised Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System which was developed by WHO. Participants also reported chronic diseases diagnosed by a physician. For this analysis, we defined chronic disease (yes/no) based on the following: (1) self-reported diabetes mellitus and/or current use of antidiabetic medications or (2) self-reported myocardial infarction, stroke and/or current use of cardiovascular disease medications or (3) self-reported cancer.

Physical measurements

Body weight, percentage fat mass, fat mass and fat-free mass were measured using the Tanita bioelectrical impedance device (Tanita BC-418; Tanita Corporation of America, Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA). Height was measured by a Seca stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. We also calculated fat mass index (FMI) and fat-free mass index (FFMI) by dividing fat mass and fat-free mass in kilograms by height in metres squared, respectively. Waist and hip circumferences were measured by using Lufin steel tape. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥102 cm for men or ≥88 cm for women.23

Among our study participants, measured data were available for 72% of participants for weight and height, 69% for both waist and hip circumferences and 70% for body composition. For participants who did not have measured anthropometric indices, self-reported measures were used in the analyses.

Statistical analyses

We computed Pearson partial correlation coefficients between fruit and vegetable intake and anthropometric measures and body composition with adjustment for age and sex. To examine the associations between fruit and vegetable intake with obesity, we derived z-scores for the intakes of total fruit and vegetable, vegetable, fruit and fruit or vegetable juice, respectively. Z-scores enable us to combine scores from the exposure variables that have different means, SDs and ranges. Further, the procedure standardises the distributions of the exposure variables and for this analysis, increased the statistical power in both the linear and logistic regression analyses when the exposure variables were treated as a continuous variable. We categorised total fruit and vegetable, vegetable, and fruit intake into low, medium and high levels according to the approximate tertiles, respectively. Fruit or vegetable juice intake was dichotomised (yes/no) as 49% of the participants did not consume fruit or vegetable juice. We used multiple linear regression models with Robust M estimator to evaluate the associations between fruit and vegetable intake with BMI, waist circumference, percentage fat mass and FMI. We employed multiple logistic regression models to compute the ORs and 95% CIs of having obesity and abdominal obesity across different levels of fruit and vegetable intake. To evaluate the independent associations between consumption of fruit, vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice with obesity, we performed both the linear and logistic regression analyses using three models: model 1 was adjusted for age, sex and province; model 2 was further adjusted for ethnicity, socioeconomic status, behavioural factors and chronic disease based on model 1 and model 3 was additionally and mutually adjusted for fruit, vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice intake based on model 2.

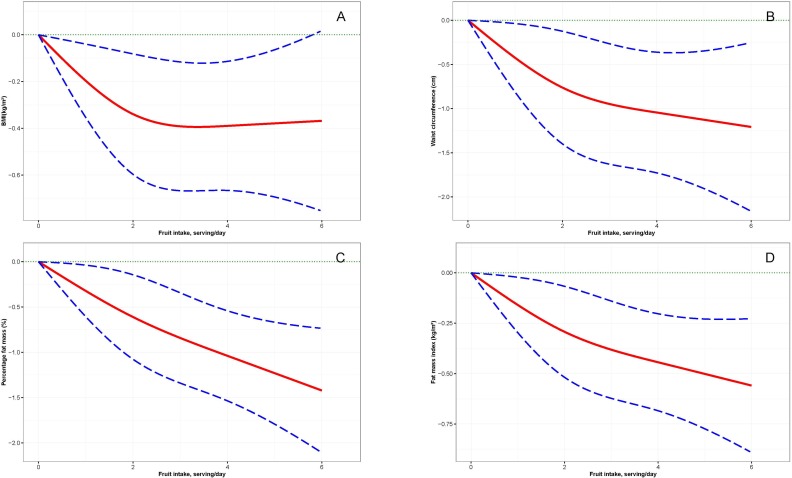

Further, as we found a consistent inverse association between daily fruit intake and adiposity, we plotted the associations of fruit intake with BMI, waist circumference, percentage fat mass and FMI by using the restricted cubic spline (RCS).24 We performed the RCS plot among participants who reported daily fruit intake ≤6 servings/day (99.5% of total participants) and used three knots located at the 5th, 50th and 95th percentiles of the fruit intake distribution. All the models were multivariable with adjustment for all of the covariables and the intakes of vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice. Given that energy expenditure has been shown to be strongly and inversely associated with body adiposity,1 19 we also analysed the interactions between fruit intake and physical activity in relation to risks of obesity and abdominal obesity. In addition, we evaluated whether substituting 1 SD of fruit intake for vegetable intake or vice versa might affect obesity risk by using multivariable logistic regression models.16 We carried out a sensitivity analysis among participants with all measured body adiposity measurements (n=17 528) and yielded a similar pattern of results. We, therefore, reported the results for the entire samples. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (two sided). Data management and analyses were performed with SAS for Windows, V.9.4.

Results

Fruit and vegetable consumption among study participants

Average total fruit and vegetable intake was 5.4 servings per day in the study participants (4.9 servings/day in men and 5.6 servings/day in women). Only 22% of men and 32% of women reported total fruit and vegetable intake ≥7 servings/day, respectively (table 1 and online supplementary table 1). The correlation between fruit or vegetable juice intake with fruit intake was higher compared with that for vegetable intake. Participants who reported high levels of fruit and vegetable intake were more likely to be females, white, married, have higher levels of education and engage in higher levels of physical activity. They were also less likely to be current smokers compared with those who reported low levels of fruit and vegetable consumption (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants*

| Characteristics | n | Men (n=7979) | n | Women (n=18 361) |

| Age, year | 54.0 (9.3) | 52.6 (9.0) | ||

| Total fruit and vegetable, serving/day | 4.9 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.6) | ||

| Vegetable, serving/day | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.5) | ||

| Fruit, serving/day | 1.8 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.3) | ||

| 100% fruit or vegetable juice, serving/day | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.6 (0.9) | ||

| Total fruit and vegetable ≥7 servings/day, n (%) | 1750 (21.9) | 5803 (31.6) | ||

| Body weight, kg | 85.0 (17.8) | 76.7 (17.8) | ||

| Body height, cm | 171.8 (8.4) | 164.4 (6.7) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.7 (5.6) | 28.4 (6.3) | ||

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.0 (14.0) | 92.7 (15.0) | ||

| Hip circumference, cm | 104.7 (10.7) | 106.1 (12.8) | ||

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.87 (0.09) | ||

| Percentage fat mass, % | 5311 | 30.8 (9.4) | 13 005 | 34.7 (8.8) |

| Fat mass index, kg/m2 | 5307 | 9.1 (4.3) | 12 997 | 10.1 (4.4) |

| Fat-free mass index, kg/m2 | 5306 | 19.4 (3.2) | 12 996 | 18.0 (3.1) |

| Province, n (%) | ||||

| Nova Scotia | 4272 (53.5) | 9639 (52.5) | ||

| New Brunswick | 2283 (28.6) | 5424 (29.5) | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1194 (15.0) | 2630 (14.3) | ||

| Prince Edward Island | 230 (2.9) | 668 (3.6) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 7178 (90.0) | 16 016 (87.2) | ||

| Non-white | 447 (5.6) | 1218 (6.6) | ||

| DNK/PNA | 354 (4.4) | 1127 (6.1) | ||

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Less than high school | 1550 (19.4) | 3293 (17.9) | ||

| College level | 2978 (37.3) | 7799 (42.5) | ||

| University level or higher | 3430 (43.0) | 7217 (39.3) | ||

| DNK/PNA | 21 (0.3) | 52 (0.3) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married or living together | 6971 (87.4) | 14 120 (76.9) | ||

| Single, divorced, separated or widowed | 988 (12.4) | 4185 (22.8) | ||

| DNK/PNA | 20 (0.3) | 56 (0.3) | ||

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 3796 (47.6) | 9461 (51.5) | ||

| Former | 3381 (42.4) | 7023 (38.2) | ||

| Current | 763 (9.6) | 1719 (9.4) | ||

| DNK/PNA | 39 (0.5) | 158 (0.9) | ||

| Alcohol drinking, n (%) | ||||

| Abstainer | 810 (10.2) | 1985 (10.8) | ||

| Occasional drinker | 2322 (29.1) | 8489 (46.2) | ||

| Regular drinker | 2793 (35.0) | 5224 (28.5) | ||

| Habitual drinker | 1833 (23.0) | 2412 (13.1) | ||

| DNK/PNA | 221 (2.8) | 251 (1.4) | ||

| Total physical activity, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 2615 (32.8) | 6032 (32.9) | ||

| Medium | 2725 (34.2) | 6144 (33.5) | ||

| High | 2628 (33.0) | 6162 (33.6) | ||

| Chronic disease†, yes, n (%) | 2618 (32.8) | 4767 (26.0) | ||

| Obesity‡, yes, n (%) | 2774 (34.8) | 6144 (33.5) | ||

| Abdominal obesity§, yes, n (%) | 2590 (32.5) | 10 951 (59.6) | ||

*Data are means (SD) and number of participants (percentage). Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

†Self-reported diabetes mellitus and/or current use of antidiabetic medications, self-reported CVD and/or current use of medications for CVD treatment and self-reported cancer.

‡BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

§Waist circumference ≥102 cm for men and ≥88 cm for women.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DNK, do not know; PNA, prefer not to answer.

bmjopen-2017-018060supp001.pdf (448.2KB, pdf)

Fruit and vegetable consumption and body adiposity

There was a consistently negative correlation between fruit and vegetable intake with body adiposity measures (online supplementary table 1). There was no statistically significant correlation between fruit and vegetable intake with FFMI.

In the multivariable linear regression analyses, 1 SD increment of total fruit and vegetable intake was inversely associated with BMI (−0.12 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.19 to –0.05), waist circumference (−0.40 cm; 95% CI −0.58 to –0.23), percentage fat mass (−0.30%; 95% CI −0.44 to –0.17) and FMI (−0.14 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.19 to –0.08) (table 2). In the multivariable logistic regression analyses, individuals with high levels of total fruit and vegetable intake had reduced likelihoods of 12% (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.83 to 0.94) for having abdominal obesity compared with those with low levels (P for trend<0.001, table 3).

Table 2.

Associations between 1 SD increment of fruit and vegetable intake with adiposity measurements

| β (95% CI) | ||||

| BMI | Waist circumference | Percentage fat mass | Fat mass index | |

| Total fruit and vegetable | ||||

| Simple model* | −0.18 (−0.25 to –0.12) | −0.67 (−0.85 to –0.50) | −0.36 (−0.49 to –0.23) | −0.16 (−0.21 to –0.10) |

| Multivariable model† | −0.12 (−0.19 to –0.05) | −0.40 (−0.58 to –0.23) | −0.30 (−0.44 to –0.17) | −0.14 (−0.19 to –0.08) |

| Vegetable | ||||

| Simple model* | −0.11 (−0.18 to –0.05) | −0.52 (−0.70 to –0.35) | −0.25 (−0.38 to –0.11) | −0.11 (−0.16 to –0.05) |

| Multivariable model† | −0.05 (−0.11 to 0.02) | −0.25 (−0.43 to –0.08) | −0.18 (−0.31 to –0.04) | −0.08 (−0.14 to –0.03) |

| Additional adjustment for fruit and fruit or vegetable juice | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.06) | −0.13 (−0.32 to 0.06) | −0.06 (−0.21 to 0.08) | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.03) |

| Fruit | ||||

| Simple model* | −0.14 (−0.21 to –0.08) | −0.57 (−0.74 to –0.39) | −0.35 (−0.48 to –0.21) | −0.15 (−0.21 to –0.10) |

| Multivariable model† | −0.09 (−0.16 to –0.03) | −0.36 (−0.53 to –0.18) | −0.31 (−0.44 to –0.17) | −0.14 (−0.19 to –0.08) |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice | −0.08 (−0.15 to –0.01) | −0.29 (−0.48 to –0.10) | −0.27 (−0.42 to –0.13) | −0.12 (−0.18 to –0.06) |

| Fruit or vegetable juice | ||||

| Simple model* | −0.13 (−0.19 to –0.06) | −0.25 (−0.42 to –0.07) | −0.13 (−0.26 to 0.01) | −0.06 (−0.11 to –0.00) |

| Multivariable model† | −0.12 (−0.18 to –0.05) | −0.20 (−0.37 to –0.03) | −0.11 (−0.25 to 0.02) | −0.05 (−0.10 to 0.01) |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit | −0.11 (−0.18 to –0.05) | −0.17 (−0.35 to 0.00) | −0.09 (−0.22 to 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.09 to 0.02) |

*Adjusted for age, sex and province.

†Adjusted for age, sex, province, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and chronic disease.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 3.

Associations of fruit and vegetable intake with obesity and abdominal obesity

| Levels of fruit and vegetable intake, OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Low | Medium | High | P for trend | |

| Obesity | ||||

| Total fruit and vegetable | <4 servings/day | ≥4, <6 servings/day | ≥6 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 3714/10 308 | 2732/8377 | 2472/7655 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.95) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | 0.150 |

| Vegetable | <2 servings/day | ≥2, <3 servings/day | ≥3 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 2451/6821 | 2654/7968 | 3813/11 551 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.98) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 0.090 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.04) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | 0.106 |

| Additional adjustment for fruit and fruit or vegetable juice | 1.0 (reference) | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.08) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) | 0.004 |

| Fruit | <1 servings/day | ≥1, <2 servings/day | ≥2 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 3226/8936 | 2870/8651 | 2822/8753 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.95) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.91) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) | 0.003 |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice | 1.0 (reference) | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.97) | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Fruit or vegetable juice | No | Yes | P values | |

| Case/n | 4524/12 816 | 4394/13 524 | ||

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.93) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.95) | <0.001 | |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit | 1.0 (reference) | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.96) | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal obesity | ||||

| Total fruit and vegetable | <4 servings/day | ≥4, <6 servings/day | ≥6 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 5307/10 308 | 4348/8377 | 3886/7655 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Vegetable | <2 servings/day | ≥2, <3 servings/day | ≥3 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 3390/6821 | 4138/7968 | 6013/11 551 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.89) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.01) | 0.066 |

| Additional adjustment for fruit and fruit or vegetable juice | 1.0 (reference) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 0.603 |

| Fruit | <1 servings/day | ≥1, <2 servings/day | ≥2 servings/day | |

| Case/n | 4479/8936 | 4562/8651 | 4500/8753 | |

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice | 1.0 (reference) | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.04) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Fruit or vegetable juice | No | Yes | P values | |

| Case/n | 6972/12 816 | 6569/13 524 | ||

| Simple model* | 1.0 (reference) | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.95) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable model† | 1.0 (reference) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 0.005 | |

| Additional adjustment for vegetable and fruit | 1.0 (reference) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 0.004 | |

*Adjusted for age, sex and province.

†Adjusted for age, sex, province, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and chronic disease.

Independent associations of fruit, vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice consumption with body adiposity

In the multivariable regression analyses, fruit consumption was consistently inversely associated with adiposity measurements (table 2 and figure 1) and the likelihoods for obesity and abdominal obesity (table 3). Compared with those with low levels of fruit consumption, individuals with medium to high levels of fruit consumption had ORs of 0.92 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.98) and 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.96) for obesity and 0.97 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.03) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.94) for abdominal obesity, respectively (all P for trend<0.05). These associations remained materially unchanged after further controlling for the intake of vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice. The similar associations were evident for juice intake but were less consistent than those observed for fruit intake. Moreover, fruit consumption was shown to have additive effects with total physical activity in terms of the likelihoods for obesity and abdominal obesity (online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 1.

Restricted cubic spline plots of the associations between daily fruit intake with body mass index (BMI) (A), waist circumference (B), percentage fat mass (C) and fat mass index (FMI) (D) among populations in Atlantic Canada*. Solid lines denote β coefficients of BMI (A), waist circumference (B), percentage fat mass (C) and FMI (D); dashed lines denote 95% CIs. *Adjusted for age, sex, province, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, chronic disease and intake of vegetable and fruit or vegetable juice.

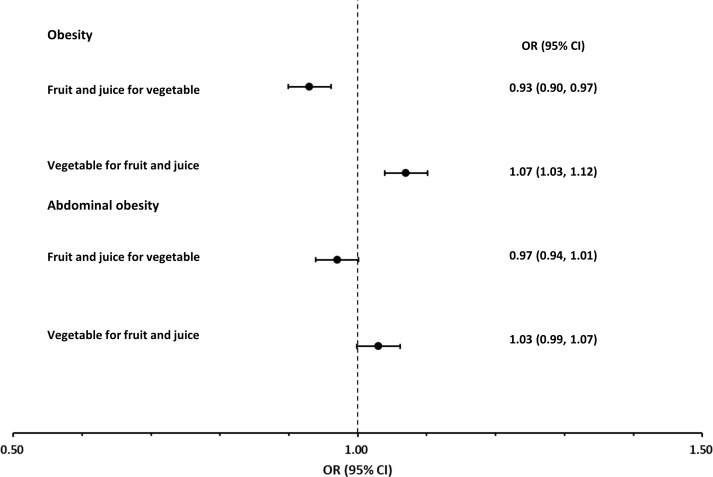

The inverse association between vegetable consumption and obesity was attenuated and became positive after further controlling for the intakes of fruit and fruit or vegetable juice (table 3). Further analyses showed that substituting 1 SD of the intakes of fruit and juice for vegetables resulted in the reduced likelihoods for obesity (figure 2 and online supplementary table 2). Conversely, substituting 1 SD of vegetable intake for fruit and juice led to the increased likelihoods for obesity.

Figure 2.

ORs (95% CIs) for obesity and abdominal obesity after alternatively replacing 1 SD of intakes of fruit and fruit and vegetable juice and vegetable*. *Adjusted for age, sex, province, ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and chronic disease.

Discussion

In this large-scale, population-based cross-sectional analysis, we found that total daily fruit and vegetable intake among Atlantic Canadians was comparable to those reported from a nationally representative sample of Canadians.25 We observed that total fruit and vegetable intake was inversely associated with body adiposity. This association appeared to be primarily attributable to fruit consumption. These findings are in line with the previous studies reporting the potentially favourable role of fruit consumption in effective body weight management.9 14 15 However, after controlling for the consumption of fruit, fruit or vegetable juice and other covariables, vegetable intake tended to be positively related to obesity. This finding is consistent with that reported in a longitudinal study carried out in American women.15 However, the mechanisms underlying these observed associations is unclear.

Thus far, substantial evidence appears to show that adequate fruit and vegetable consumption reduces the risk of chronic disease.26 With respect to body weight management, regular daily fruit consumption may displace energy-dense foods, resulting in attenuated dietary energy density and reduced total energy intake.27 Fruits have abundant soluble dietary fibres which may enhance postmeal satiety and decrease both glycaemic index and glycaemic load of consumed foods causing lowered energy absorption.28 Moreover, fruits are rich in phytochemicals that have antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects against the obesity-induced oxidative stress and subclinical inflammation.26 29 While most vegetables have these characteristics, in multivariable regression analyses, we observed a different association between vegetable intake and obesity from those for fruit consumption.

In our analyses, the association between 100% fruit or vegetable juice and obesity was similar to the association between fruit and obesity. Some longitudinal studies have shown that a vegetable-rich dietary pattern might lead to increased body weight30 and an unhealthful plant-based diet that was featured with sweetened foods and beverages, refined grains, and potatoes might be related to increased incidence of type 2 diabetes.31 Regular potato intake, especially french fries, was associated with obesity.32 These findings may imply that some fatty substances added during the preparation of vegetables and the type of vegetable consumed (eg, starchy vegetables) might play a role in the positive association between increasing vegetable intake and increasing obesity. Our data appeared to support this hypothesis as oil products and starchy vegetables are seldom used to prepare 100% juice. Nevertheless, further research is needed to clarify the potential role of vegetable intake in obesity development.

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale, population-based study investigating the associations between fruit and vegetable intake with objectively measured body composition. Our findings imply that fruit and vegetable consumption may need to be assessed separately to evaluate the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and body weight changes. To investigate the influence of fruit and vegetable intake on body weight management, body fat mass assessment may be considered as an important measurement along with anthropometrics.

The large sample size and the objectively measured body composition are major strengths of this study. Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. First, our study participants were recruited as volunteers of the Atlantic PATH cohort; therefore, our study sample was not a representative sample of the populations of Atlantic Canada. The majority were Caucasians and about 70% of study participants were females.18 Thus, this may limit the generalisability of our current cross-sectional study findings to other populations. Second, due to the constraints of the data collection, we were not able to calculate the total energy intake of study participants and analyse the associations between different types of fruit and vegetable consumption with the study outcomes. However, we controlled for total physical activity in the multivariable regression analyses and found an additive effect of the interactions between fruit intake and physical activity on obesity risk. These findings suggested that the observed association between fruit intake and obesity risk was independent of energy expenditure. Third, though we collected data on the habitual fruit, vegetable and 100% juice intake, the cross-sectional nature of the study design did not enable us to make either temporal or causal inference.

In summary, our findings suggested that higher levels of fruit and vegetable consumption were associated with lower levels of body adiposity. Fruit intake was consistently inversely associated with fat mass and obesity. While evidence regarding the positive health effects of vegetable consumption on chronic disease is substantial,26 our findings may indicate that further research is needed to investigate whether the types of vegetable consumed and culinary approaches adopted for vegetable preparation are also important for the effective management of body weight. Given four in five men and two in three women in our study populations did not report adequate fruit and vegetable intake, there is a need to implement comprehensive intervention strategies to promote frequent and adequate fruit and vegetable consumption across Atlantic Canada.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of all participants in the Atlantic PATH Project. We thank the Atlantic PATH team members for data collection and management.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study conception and design: ZMY, LP and TJBD. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of manuscript: ZMY. Critical revision of the article: VD, YC, CF, SG, MK, LP, ES and TJBD. All authors have full access to all the data in the study, take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and give final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding: Production of this study has been made possible through the financial support from the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and Health Canada.

Disclaimer: The study funders had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed herein represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by appropriate Research Ethics Boards in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No datasets were generated during the current study. Data from the Atlantic PATH study are not publicly available to researchers without an approved data access request to Atlantic PATH, as per the Atlantic PATH consent form and study protocol. While the authors cannot provide data to a third party directly, the dataset can be provided by Atlantic PATH following a data access request approval. Interested researchers should contact Atlantic PATH (http://atlanticpath.ca/).

References

- 1. Haslam DW, James WPT. Obesity. The Lancet 2005;366:1197–209. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Twells LK, Gregory DM, Reddigan J, et al. . Current and predicted prevalence of obesity in Canada: a trend analysis. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E18–E26. 10.9778/cmajo.20130016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Health Canada. How many food guide servings of fruits and vegetables do I need? - Canada’s food guide. 2007. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/choose-choix/fruit/need-besoin-eng.php (accessed 14 Mar 2016).

- 4. Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. . Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014;349:g4490 10.1136/bmj.g4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Du H, Li L, Bennett D, et al. . Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1332–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He FJ, Nowson CA, MacGregor GA. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006;367:320–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper AJ, Sharp SJ, Lentjes MA, et al. . A prospective study of the association between quantity and variety of fruit and vegetable intake and incident type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1293–300. 10.2337/dc11-2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradbury KE, Appleby PN, Key TJ. Fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake in relation to cancer risk: findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100(Suppl 1):394S–8. 10.3945/ajcn.113.071357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alinia S, Hels O, Tetens I. The potential association between fruit intake and body weight--a review. Obes Rev 2009;10:639–47. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ledoux TA, Hingle MD, Baranowski T. Relationship of fruit and vegetable intake with adiposity: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2011;12:e143–50. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mytton OT, Nnoaham K, Eyles H, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of increased vegetable and fruit consumption on body weight and energy intake. BMC Public Health 2014;14:886 10.1186/1471-2458-14-886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Kalle-Uhlmann T, et al. . Fruit and vegetable consumption and changes in anthropometric variables in adult populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140846 10.1371/journal.pone.0140846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaiser KA, Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, et al. . Increased fruit and vegetable intake has no discernible effect on weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:567–76. 10.3945/ajcn.114.090548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drapeau V, Després JP, Bouchard C, et al. . Modifications in food-group consumption are related to long-term body-weight changes. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:29–37. 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rautiainen S, Wang L, Lee IM, et al. . Higher intake of fruit, but not vegetables or fiber, at baseline is associated with lower risk of becoming overweight or obese in middle-aged and older women of normal BMI at baseline. J Nutr 2015;145:960–8. 10.3945/jn.114.199158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borugian MJ, Robson P, Fortier I, et al. . The Canadian partnership for tomorrow project: building a pan-Canadian research platform for disease prevention. CMAJ 2010;182:1197–201. 10.1503/cmaj.091540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sweeney E, Cui Y, DeClercq V, et al. . Cohort profile: the Atlantic Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (Atlantic PATH) Study. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1762–3. 10.1093/ije/dyx124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu ZM, Parker L, Dummer TJ. Depressive symptoms, diet quality, physical activity, and body composition among populations in Nova Scotia, Canada: report from the Atlantic Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health. Prev Med 2014;61:106–13. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. . International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. IPAQ scoring protocol. International physical activity questionnaire. https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol (accessed 28 Oct 2016).

- 22. Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, et al. . Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol 1994;10:405–11. 10.1007/BF01719664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. . Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med 2010;29:1037–57. 10.1002/sim.3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Black JL, Billette JM. Do Canadians meet Canada’s Food Guide’s recommendations for fruits and vegetables? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2013;38:234–42. 10.1139/apnm-2012-0166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A, et al. . Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr 2012;51:637–63. 10.1007/s00394-012-0380-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Oliveira MC, Sichieri R, Venturim Mozzer R. A low-energy-dense diet adding fruit reduces weight and energy intake in women. Appetite 2008;51:291–5. 10.1016/j.appet.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Howarth NC, Saltzman E, Roberts SB. Dietary fiber and weight regulation. Nutr Rev 2001;59:129–39. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb07001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu RH. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: mechanism of action. J Nutr 2004;134:3479S–85. 10.1093/jn/134.12.3479S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi Z, Yuan B, Hu G, et al. . Dietary pattern and weight change in a 5-year follow-up among Chinese adults: results from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study. Br J Nutr 2011;105:1047–54. 10.1017/S0007114510004630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, et al. . Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002039 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borch D, Juul-Hindsgaul N, Veller M, et al. . Potatoes and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: a systematic review of clinical intervention and observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:489–98. 10.3945/ajcn.116.132332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018060supp001.pdf (448.2KB, pdf)