Abstract

Introduction

Fatigue is the second most common symptom in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Despite its high prevalence, fatigue is often ignored in daily practice. For this reason, little is known about the underlying determinants of fatigue in patients with COPD. The primary objectives of this study are to chart the course of fatigue in patients with COPD, to identify the physical, systemic, psychological and behavioural factors that precipitate and perpetuate fatigue in patients with COPD, to evaluate the impact of exacerbation-related hospitalisations on fatigue and to better understand the association between fatigue and 2-year all-cause hospitalisation and mortality in patients with COPD. The secondary aim is to identify diurnal differences in fatigue by using ecological momentary assessment (EMA). This manuscript describes the protocol of the FAntasTIGUE study and gives an overview of the possible strengths, weaknesses and clinical implications.

Methods and analysis

A 2-year longitudinal, observational study, enrolling 400 patients with clinically stable COPD has been designed. Fatigue, the primary outcome, will be measured by the subjective fatigue subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-Fatigue). The secondary outcome is the day-to-day/diurnal fatigue, registered in a subsample (n=60) by EMA. CIS-Fatigue and EMA will be evaluated at baseline, and at 4, 8 and 12 months. The precipitating and perpetuating factors of fatigue (physical, psychological, behavioural and systemic) will be assessed at baseline and at 12 months. Additional assessments will be conducted following hospitalisation due to an exacerbation of COPD that occurs between baseline and 12 months. Finally, at 18 and 24 months the participants will be followed up on their fatigue, number of exacerbations, exacerbation-related hospitalisation and survival.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol was approved by the Medical research Ethics Committees United, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands (NL60484.100.17).

Trial registration number

NTR6933; Pre-results.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fatigue, underlying factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large, longitudinal, multicentre study evaluating a wide range of possible precipitating and perpetuating factors of mild to severe fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The ecological momentary assessment data will give us more insight in the diurnal variations of fatigue.

The longitudinal design enables to examine the association between fatigue, exacerbation-related hospitalisations and mortality and allows us to investigate whether the associations between fatigue and the explaining factors are temporary or fluctuate over time.

The perpetuating and precipitating factors have been carefully selected; it is—however—possible that there are other factors that contribute to fatigue in COPD that will be missed.

Introduction

Fatigue, the subjective feeling of tiredness or exhaustion, is next to dyspnoea, the most common and distressing symptom in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 It affects the ability to perform activities of daily living and impacts the patient’s quality of life.2 3 Among patients with stable moderate to severe COPD, around 50% experiences mild to severe fatigue,4 which is significantly higher compared with elderly, non-COPD subjects.5 Nevertheless, despite its high prevalence and significant negative health consequences, fatigue remains often undiagnosed and, in turn, untreated.6 This might be due to the under-representation of fatigue questions in commonly used health status assessment tools.7 8 Moreover, relatively few studies have focused on the symptom fatigue and, therefore, little is known about the precipitating and perpetuating factors of mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. Consequently, specific interventions aimed at reducing COPD-related fatigue are lacking. A better insight into the underlying determinants will provide guidance for the development of personalised interventions for this important yet disregarded symptom in patients with COPD.9

Multiple precipitating factors are expected to play a role in the cause of COPD-related fatigue.9 It has been suggested that COPD-specific features are associated with fatigue, since the prevalence of fatigue is higher in patients with COPD compared with elderly control subjects.5 However, evidence suggests that fatigue is not related to the degree of airflow limitation.4 This indicates that the degree of airflow limitation may not be the primary underlying cause of mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. On the other hand, a COPD exacerbation precipitates mild to severe fatigue.5 10 However, the size of the impact of an exacerbation-related hospitalisation on fatigue remains to be clarified.

Next to precipitating factors, various physical, systemic, psychological and behavioural factors are assumed to perpetuate mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. Generally, studies report significant, weak to moderate associations between fatigue and health status, exercise performance, physical activity, functional impairments, sleep quality, symptoms of anxiety or depression and mood status.2 5 11–15 Moreover, research indicates that COPD is associated with low-grade systemic inflammation.16 Nonetheless, whether and to what extent low-grade systemic inflammation is related to fatigue needs to be further explored.

Thus, fatigue in COPD is a complex symptom, due to a combination of precipitating and perpetuating factors. To date, the above-mentioned factors have rarely been assessed comprehensively in one study in patients with COPD.17 Moreover, the role of sleep apnoea, comorbidities, medication and exacerbation-related hospitalisations are unknown. Therefore, we have designed a longitudinal, observational study, which evaluates a wide range of possible underlying factors of mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. This manuscript describes the protocol of the FAntasTIGUE study and gives an overview of its possible strengths, weaknesses and clinical implications.

Objectives of this study

The primary objectives of the FAntasTIGUE study are:

To chart the course of fatigue in patients with COPD.

To identify physical, systemic, psychological and behavioural factors that precipitate and/or perpetuate fatigue in patients with COPD.

To identify the impact of exacerbation-related hospitalisations on fatigue and its perpetuating factors.

To better understand the association between baseline fatigue and 2-year all-cause hospitalisation and mortality in patients with COPD.

The secondary objective of this study is:

To identify diurnal differences in fatigue by augmenting traditional questionnaire data with ecological momentary assessment (EMA).

Methods

The FAntasTIGUE study is a collaboration between CIRO (Horn, The Netherlands), Radboud University Medical Centre (Nijmegen, The Netherlands), Academic Medical Centre (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Maastricht University Medical Centre (Maastricht, The Netherlands) and Hasselt University (Diepenbeek, Belgium). The consortium consists of members from various disciplines and backgrounds (eg, chest physicians, clinical psychologists, an elderly care specialist, a cardiologist, a general practitioner and researchers), to ensure necessary know-how to enable the successful completion of the project. Moreover, a patient advisory board is closely involved to advise and monitor the FAntasTIGUE project, by providing valuable insight from the patient perspective.

Patient and public involvement

Based on the input of patients with chronic lung disease, fatigue was prioritised as a research topic during the Netherlands Respiratory Society meeting (www.nationaalprogrammalongonderzoek.nl).18 As stated, patient representatives are full members of the FAntasTIGUE consortium, and have an active role in the decision process. The patient advisory board has been involved in setting up the proposal, in reviewing the study design before submission to the ethical committee and in discussing the schedules of assessment. After completion of the study, the patient advisory board will also be asked to be involved in the development of post-trial communication.

Study design

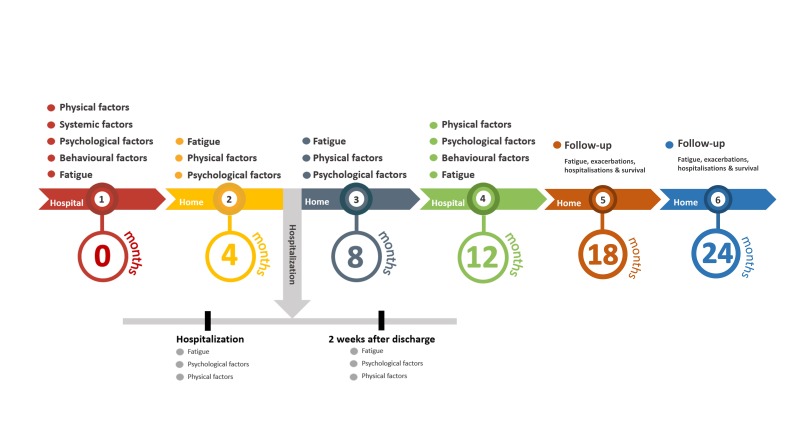

A 2-year longitudinal, observational study, enrolling patients with clinically stable COPD has been designed (figure 1). The assessments at baseline, 12 months and during the first 4 days of a possible exacerbation-related hospitalisation will be performed in a hospital setting. The remaining measurements at 4, 8, 18 and 24 months will take place at the patients’ homes.

Figure 1.

Timeline: measurements will be performed at baseline, and at months 4, 8 and 12. Additional measurements will be carried out when a non-elective, exacerbation-related hospitalisation occurs. Patients will be followed up at month 18 and 24.

The primary outcome fatigue severity will be assessed with a questionnaire at baseline, and at 4, 8, 12, 18 and 24 months, as well as during exacerbation-related hospitalisations and 2 weeks after discharge. The secondary outcome, day-to-day/diurnal variation in fatigue, will be registered using EMA in a subsample (n=60) at baseline, and at 4, 8 and 12 months. Selection is based on convenient sampling, a ‘first-come, first-serve’ approach. The precipitating and perpetuating factors of mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD (physical, psychological, behavioural and systemic factors) will be assessed at baseline and at 12 months. Also, when patients are admitted to the hospital between baseline and 12 months due to an exacerbation of COPD, some tests will be repeated during the first 4 days of hospitalisation and 2 weeks after discharge. At last, at 18 and 24 months the participants will be followed up on their fatigue, number of exacerbations, exacerbation-related hospitalisations and survival.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible, a subject must meet the following criteria:

A diagnosis of COPD according to the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD (GOLD, grade 1A–4D), with a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio, FEV1/FVC <0.7.19

No exacerbation-related hospitalisation less than 4 weeks preceding enrolment.

No use of oral corticosteroids and/or antibiotics less than 4 weeks preceding enrolment.

Provided written informed consent.

Patients lacking a sufficient understanding of the Dutch language and/or participating in concurrent intervention studies will be excluded. There are no age or smoking status restrictions, as well as no exclusion based on comorbidities or the use of long-term oxygen therapy.

Extra eligibility criteria for the EMA substudy are as follows:

Access to the internet at home (Wi-Fi).

Able to operate a smartphone/iPod.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited at the outpatient clinics of the Department of Respiratory Medicine in Maastricht and the Department of Pulmonary Diseases in Nijmegen, and from the registration Network of Family Practices (RNH) of Maastricht University.20 Eligible patients from the outpatient clinics will be informed about the research by their physician during their pulmonary consultation and are asked if the investigator may contact them to provide detailed information. Patients recruited via the RNH network will receive a letter on behalf of their general practitioner introducing the research project. In case the patient agrees to participate, an appointment for the baseline assessment at the hospital will be made. Written informed consent will be obtained at the beginning of this visit.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Fatigue severity will be measured by the subjective fatigue subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-Fatigue).21 The CIS-Fatigue consists of eight items scored on a seven-point Likert scale. The scores range from 8 (normal fatigue) to 56 (most severe fatigue). A score of 26 or lower indicates normal fatigue, scores between 27 to 35 indicate mild fatigue and a score of 36 or higher indicates severe fatigue. The CIS-Fatigue is a standardised and validated questionnaire that has been used in healthy subjects,22–24 and among various patient populations including COPD.21 25–27 The CIS-Fatigue will be administered at baseline, and at 4, 8, 12, 18 and 24 months, as well as during exacerbation-related hospitalisations and 2 weeks after discharge.

Secondary outcome

Day-to-day/diurnal variations of fatigue will be measured in a subsample (n=60) with EMA.28 29 EMA involves repeated measurements of the participant’s behaviour and context in vivo and in real time. In the current study, the participants will be given an iPod for the duration of the study with the EMA application (www.psymate.eu) installed. The participants will be prompted to answer questions about their fatigue, context and surroundings, eight times per day at random moments between 7:30 and 22:30 for five consecutive days at baseline, and at 4, 8 and 12 months. Patients will be given instructions to carry the device with them at all times for five consecutive days. Furthermore, they will be requested to fill out the questions immediately after the alert and to keep a normal day/night routine.

Explanatory factors

Table 1 provides an overview of the precipitating and perpetuating factors of mild to severe fatigue that will be assessed at baseline, and at months 4, 8, 12, 18 and 24, as well as during non-elective, exacerbation-related hospitalisations and 2 weeks after discharge.

Table 1.

Overview outcome measurements

| Number (n) | 0 month | 4 months | 8 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | Exacerbation-related hospitalisations* | |

| Fatigue | ||||||||

| Subjective fatigue subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-Fatigue)21 | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Ecological momentary assessment28 29 | 60 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||||

| Gender | 400 | • | ||||||

| Age | 400 | • | ||||||

| Social-economic status34 | 400 | • | ||||||

| Marital status | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Survival status | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Physical factors | ||||||||

| Current medication | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index35 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Symptoms checklist36 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale37 | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Exacerbations last 4 or 6 months (as appropriate) | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| All-cause hospitalisations | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Body mass index | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Waist circumference | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Bioelectrical impedance analyses38 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| 6 min Walk Test39 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Short Physical Performance Battery40 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Lower limb muscle function (MicroFet2 Wireless Hand-held Dynamometer)41 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Hand grip strength42 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Lung function (postbronchodilator spirometry, whole-body plethysmography, and transfer factor for carbon monoxide) | 400 | • | ||||||

| Peripheral arterial disease (Dopplex D900, Huntleigh Healthcare, Cardiff, UK)43 44 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Resting cardiac echocardiography (Maastricht only) | 200 | • | ||||||

| Resting ECG(Maastricht only) | 200 | • | ||||||

| Retinal microcirculation45 (Maastricht only) | 200 | • | ||||||

| Polysomnography (Maastricht only) | 50 | • | ||||||

| Psychological factors | ||||||||

| Nijmegen Clinical Screening Instrument46 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| COPD Assessment Test8 | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Euroqol-5d-5L47 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale48 | 400 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment49 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Qualitative experience of fatigue (KWAMOE)50 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Acceptance of Disease and Impairments Questionnaire51 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Fatigue-related self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy-5)52 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Jacobsen Fatigue Catastrophising Scale53 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Fear of Progression Questionnaire54 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Patient Activations Measure55 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Activity Cognitions Instrument (self-developed questionnaire) | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Behavioural factors | ||||||||

| Smoking status | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Alcohol consumption | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Caffeine consumption | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Objectified physical activity (Actigraph GT9X Link, 3-axis activity monitor, sample frequency 30 Hz)56 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index57 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale58 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Causal Attribution List59 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Sickness Impact Profile60 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Social Support List, Interactions and Discrepancies61 | 400 | • | • | |||||

| Systemic factors | ||||||||

| Venous blood samples | 400 | • |

*Non-elective hospitalisations due to an exacerbation of COPD may occur at any moment after the start of the study. Those which occur between baseline and 12 months will result in additional measurements. Those which may occur between 12 and 24 months will not result in additional measurement.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mMRC, modified Medical Research Counsil

Questionnaires will be completed via RadQuest in the home environment. RadQuest allows very simple online questionnaire completion. If, for any reason (eg, no PC or internet connection) it is not possible to fill out the questionnaires via RadQuest, the participant will receive a paper version. Regarding the systemic factors, we will collect blood at baseline to assess systemic high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1-RA, IL-10, fibrinogen, leukocytes, cortisol, haemoglobin, glucose, thyroid function, renal function (creatinine), sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, vitamin B12, vitamin 25(OH)D3, liver function (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase), N-Terminal pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide, blood sediment, antinuclear antibodies and DNA.

Sample size calculation

A total of 260 patients are needed to detect a medium to small effect size of 0.175 between factors (218 (2 groups with or without an exacerbation) or 264 (3 groups normal, mild or severe fatigue)) and a small effect within-between factors (222 (3 groups normal, mild or severe fatigue)), with a power of 90%, a significance level of 5% and an expected drop-out rate of 20%.30 Nevertheless, as a rather large number of possible perpetuating and precipitating factors will be evaluated, it is decided to augment the sample size to 400 inclusions.

For EMA, a sample of 60 patients with each 160 observations (5 days with eight measurements, collected over four time points) ensures that the EMA analyses are adequately powered to detect differences in fatigue, based on a power of 0.8 and two-tailed significance of 0.05.31

Data management and statistical analysis

Missing data of questionnaires will be minimised using RadQuest, since items cannot be skipped. In case of missing data for other variables, the likeliness of this being missing at random will be assessed. If missing data are random, we will use appropriate imputation methods.32

All statistical analyses will be performed using statistics software (SPSS V.25.0 for Windows). First, to characterise transitions over time in fatigue, we will use latent transition analysis.33 Second, to identify the factors that precipitate and/or perpetuate fatigue in patients with COPD, mixed model analyses will be applied for continuous outcomes measures and generalised estimating equations for dichotomous outcomes measures. Third, to study the impact of exacerbation-related hospitalisations on fatigue and its perpetuating factors we will use mixed model analyses. Fourth, to better understand the extent to which baseline fatigue is related to 2-year all-cause hospitalisation and mortality, Cox proportional hazard models will be applied. At last, to identify whether there are diurnal differences in fatigue and what factors are associated with these variations, we will use hierarchical linear modelling as items are nested within moments and moments are nested within individuals. The responsiveness and sensitivity of the fatigue questionnaire versus EMA data are compared with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the component of observed change derived from model parameters. A priori, a two-tailed p value of <0.05 is considered significant.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO). The study was registered on www.trialregister.nl on 8 January 2018. The results will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals and will be presented at (inter)national conferences.

Discussion

The FAntasTIGUE study has been designed to identify the factors that perpetuate and/or precipitate mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. The novel findings will hopefully further guide the development of tailored interventions, which—in turn—will help to diminish the impact on daily life of this important yet ignored symptom.

Strengths

A major strength of the FAntasTIGUE study is that a wide range of possible precipitating and perpetuating factors will be tested concurrently in one model of stable patients with COPD. Moreover, the FAntasTIGUE study also examines the impact of an exacerbation-related hospitalisation on fatigue. This way, we aim to identify relevant factors that explain variance in fatigue. Another strength of this study is the use of EMA to capture diurnal variations of fatigue in patients with COPD. In comparison with the usual web-based or paper-and-pencil questionnaires, data gathered via EMA are not subject to recall bias and provide us with a film of variations in the patient’s fatigue in their natural environment rather than a snapshot. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses EMA to evaluate fatigue in a population of patients with COPD. The information about the diurnal variations of fatigue will further help us to tailor interventions for reducing fatigue in patients with COPD. Moreover, EMA provides us with contextual information of factors that could precipitate or perpetuate fatigue. A methodological strength of this study is the longitudinal design. It enables us to examine the association between fatigue, exacerbation-related hospitalisations and mortality. Moreover, it allows us to investigate if the associations between fatigue and the precipitating and perpetuating factors are temporarily or can change over time. And last, the structure of the FAntasTIGUE consortium, including a steering committee and a patient’s advisory board, allows us to improve the research capacity, to share (academic) resources, to disseminate study results and to speed up future research.

Limitations

The present study may encounter the following limitations: first, despite the benefits of repeated measurements in longitudinal studies, higher drop-out rates are expected as disease progresses. This attrition could result in a biased sample, which may compromise the study’s generalisability. To limit the loss to follow-up, we will minimise the burden as much as possible and keep close contact with the patients. The patient advisory board has been intimately involved in the design of the FAntasTIGUE project to balance patient burden and number of variables that needed to be assessed to identify the factors that perpetuate and/or precipitate mild to severe fatigue in patients with COPD. Second, the current study selection is based on convenience sampling. This may cause selection bias, since participants with a lack of motivation and a higher disease burden are less likely to respond. We will try to prevent selection bias, by inviting all patients who are diagnosed with COPD either via their physician during consultation hour or via their own general practitioner. Third, together with the steering committee and patient advisory board, the perpetuating and precipitating factors that will be evaluated have been carefully selected. However, we still may miss other factors that potentially contribute to fatigue in COPD.

Clinical implications

The results of the FAntasTIGUE study will contribute to a better understanding of the physical, psychological, behavioural and systemic factors that precipitate and/or perpetuate fatigue in patients with COPD when studied concurrently. Furthermore, it will give us more insight in the diurnal variations of fatigue and the impact of exacerbations on fatigue. These findings will provide further guidance for the development of fatigue-reducing and coping interventions to improve the daily functioning of patients with COPD. This will be an important first step in the management of COPD-related fatigue.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YMJG and ML are responsible for the recruitment, data collection and data analysis. JHV is the principal investigator of Radboud University Medical Centre. EFWM is the principal investigator of Maastricht University Medical Centre and MAS is the project leader. Together with DJAJ, MSYT, JBPe, CB, JWMM, MAGS and JBPr, they form the FAntasTIGUE consortium, and are responsible for the design, recruitment and interpretation of the results. YM and AC are members of the patient advisory board. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This project is supported by grant 4.1.16.085 of Lung Foundation Netherlands, Leusden, the Netherlands; AstraZeneca Netherlands; Boehringer Ingelheim Netherlands; and Stichting Astma Bestrijding, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Competing interests: Professor Spruit discloses receiving personal remuneration for consultancy and/or lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis and AstraZeneca outside the scope of this work.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Medical Research Ethics Committees United approved the study, Nieuwegein, theNetherlands, on 22 December 2017 (R17.036/NL60484.100.17).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Janson-Bjerklie S, Carrieri VK, Hudes M. The sensations of pulmonary dyspnea. Nurs Res 1986;35:154???161–9. 10.1097/00006199-198605000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kapella MC, Larson JL, Patel MK, et al. Subjective fatigue, influencing variables, and consequences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nurs Res 2006;55:10–17. 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stridsman C, Skär L, Hedman L, et al. Fatigue affects health status and predicts mortality among subjects with COPD: report from the population-based OLIN COPD study. COPD 2015;12:199–206. 10.3109/15412555.2014.922176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peters JB, Heijdra YF, Daudey L, et al. Course of normal and abnormal fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and its relationship with domains of health status. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:281–5. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baghai-Ravary R, Quint JK, Goldring JJ, et al. Determinants and impact of fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2009;103:216–23. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Uszko-Lencer NH, et al. Symptoms, comorbidities, and health care in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or chronic heart failure. J Palliat Med 2011;14:735–43. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, et al. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:13 10.1186/1477-7525-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spruit MA, Vercoulen JH, Sprangers MAG, et al. Fatigue in COPD: an important yet ignored symptom. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:542–4. 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30158-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodriguez-Roisin R. Toward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbations. Chest 2000;117(Suppl 2):398S–401. 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.398S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inal-Ince D, Savci S, Saglam M, et al. Fatigue and multidimensional disease severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Multidiscip Respir Med 2010;5:162–7. 10.1186/2049-6958-5-3-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lewko A, Bidgood PL, Garrod R. Evaluation of psychological and physiological predictors of fatigue in patients with COPD. BMC Pulm Med 2009;9:47 10.1186/1471-2466-9-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woo K. A pilot study to examine the relationships of dyspnoea, physical activity and fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2000;9:526–33. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Breukink SO, Strijbos JH, Koorn M, et al. Relationship between subjective fatigue and physiological variables in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 1998;92:676–82. 10.1016/S0954-6111(98)90517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hanania NA, Müllerova H, Locantore NW, et al. Determinants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:604–11. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0472OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al-shair K, Kolsum U, Dockry R, et al. Biomarkers of systemic inflammation and depression and fatigue in moderate clinically stable COPD. Respir Res 2011;12:3 10.1186/1465-9921-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kentson M, Tödt K, Skargren E, et al. Factors associated with experience of fatigue, and functional limitations due to fatigue in patients with stable COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2016;10:410–24. 10.1177/1753465816661930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Postma DS, Wijkstra PJ, Hiemstra PS, et al. The Dutch national program for respiratory research. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:356–7. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30035-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. From the Global Strategy fort he diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD, global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). http://www.goldcopd.org/ (accessed 27 Oct 2017).

- 20. Metsemakers JF, Höppener P, Knottnerus JA, et al. Computerized health information in The Netherlands: a registration network of family practices. Br J Gen Pract 1992;42:102–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF, et al. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 1994;38:383–92. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90099-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beurskens AJ, Bültmann U, Kant I, et al. Fatigue among working people: validity of a questionnaire measure. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:353–7. 10.1136/oem.57.5.353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bültmann U, de Vries M, Beurskens AJ, et al. Measurement of prolonged fatigue in the working population: determination of a cutoff point for the checklist individual strength. J Occup Health Psychol 2000;5:411–6. 10.1037/1076-8998.5.4.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Worm-Smeitink M, Gielissen M, Bloot L, et al. The assessment of fatigue: Psychometric qualities and norms for the Checklist individual strength. J Psychosom Res 2017;98:40–6. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Repping-Wuts H, Fransen J, van Achterberg T, et al. Persistent severe fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Nurs 2007;16 377–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Servaes P, Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, et al. The course of severe fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2007;16:787–95. 10.1002/pon.1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vercoulen JH, Daudey L, Molema J, et al. An Integral assessment framework of health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Int J Behav Med 2008;15:263–79. 10.1080/10705500802365474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maes IH, Delespaul PA, Peters ML, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life by experiences: the experience sampling method. Value Health 2015;18:44–51. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larson RWC M. The experience sampling method New directions for naturalistic methods in the behavioral sciences. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gelman A, Hill J. Multilevel power calculation using fake-data simulation: data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andrykowski MA, Aarts MJ, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Low socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes in colorectal cancer survivors: disadvantage? advantage?… or both? Psychooncology 2013;22:2462–9. 10.1002/pon.3309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983;16:87–101. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90088-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580–6. 10.1378/chest.93.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schols AM, Wouters EF, Soeters PB, et al. Body composition by bioelectrical-impedance analysis compared with deuterium dilution and skinfold anthropometry in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:421–4. 10.1093/ajcn/53.2.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. 10.1183/09031936.00150314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernabeu-Mora R, Medina-Mirapeix F, Llamazares-Herrán E, et al. The short physical performance battery is a discriminative tool for identifying patients with COPD at risk of disability. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:2619–26. 10.2147/COPD.S94377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bohannon RW, Andrews AW. Interrater reliability of hand-held dynamometry. Phys Ther 1987;67:931–3. 10.1093/ptj/67.6.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bechtol CO, test G. Grip test; the use of a dynamometer with adjustable handle spacings. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1954;36-A 820–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;126:2890–909. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Houben-Wilke S, Jörres RA, Bals R, et al. Peripheral artery disease and its clinical relevance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the copd and systemic consequences-comorbidities network study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:189–97. 10.1164/rccm.201602-0354OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Boever P, Louwies T, Provost E, et al. Fundus photography as a convenient tool to study microvascular responses to cardiovascular disease risk factors in epidemiological studies. J Vis Exp 2014;92:e51904 10.3791/51904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peters JB, Daudey L, Heijdra YF, et al. Development of a battery of instruments for detailed measurement of health status in patients with COPD in routine care: the Nijmegen Clinical Screening Instrument. Qual Life Res 2009;18:901–12. 10.1007/s11136-009-9502-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 1997;27:363–70. 10.1017/S0033291796004382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Villeneuve S, Pepin V, Rahayel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in moderate to severe COPD: a preliminary study. Chest 2012;142:1516–23. 10.1378/chest.11-3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gielissen MF, Knoop H, Servaes P, et al. Differences in the experience of fatigue in patients and healthy controls: patients' descriptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:36 10.1186/1477-7525-5-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boer LM, Daudey L, Peters JB, et al. Assessing the stages of the grieving process in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): validation of the Acceptance of Disease and Impairments Questionnaire (ADIQ). Int J Behav Med 2014;21:561–70. 10.1007/s12529-013-9312-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Galama JM, et al. The persistence of fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis: development of a model. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:507–17. 10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, Thors CL. Relationship of catastrophizing to fatigue among women receiving treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:355–61. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kwakkenbos L, van den Hoogen FH, Custers J, et al. Validity of the fear of progression questionnaire-short form in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:930–4. 10.1002/acr.21618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 2005;40:1918–30. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rabinovich RA, Louvaris Z, Raste Y, et al. Validity of physical activity monitors during daily life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2013;42:1205–15. 10.1183/09031936.00134312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Ann Oncol 2002;13:589–98. 10.1093/annonc/mdf082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, et al. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981;19:787–805. 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sonderen E. Het meten van sociale steun met de Sociale Steun Lijst-Interacties (SSLI-I) en de Sociale Steun Lijst-Discrepancies (SSL-D), een handleiding [Assessing social support with the Social Support List-Interactions (SSL-I) and the social support list-discrepancies, a manual]. Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.