Abstract

Background

To achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC), more health workers are needed; also critical is supporting optimal performance of existing staff. Integrated human resource management (HRM) strategies, complemented by other health systems strategies, are needed to improve health workforce performance, which is possible at district level in decentralised contexts. To strengthen the capacity of district management teams to develop and implement workplans containing integrated strategies for workforce performance improvement, we introduced an action-research-based management strengthening intervention (MSI). This consisted of two workshops, follow-up by facilitators and meetings between participating districts. Although often used in the health sector, there is little evaluation of this approach in middle-income and low-income country contexts. The MSI was tested in three districts in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda. This paper reports on the appropriateness of the MSI to the contexts and its effects.

Methods

Documentary evidence (workshop reports, workplans, diaries, follow-up visit reports) was collected throughout the implementation of the MSI in each district and interviews (50) and focus-group discussions (6) were conducted with managers at the end of the MSI. The findings were analysed using Kirkpatrick’s evaluation framework to identify effects at different levels.

Findings

The MSI was appropriate to the needs and work patterns of District Health Management Teams (DHMTs) in all contexts. DHMT members improved management competencies for problem analysis, prioritisation and integrated HRM and health systems strategy development. They learnt how to refine plans as more information became available and the importance of monitoring implementation. The MSI produced changes in team behaviours and confidence. There were positive results regarding workforce performance or service delivery; these would increase with repetition of the MSI.

Conclusions

The MSI is appropriate to the contexts where tested and can improve staff performance. However, for significant impact on service delivery and UHC, a method of scaling up and sustaining the MSI is required.

Keywords: intervention study, health services research, public health

Key questions.

What is already known?

There is a recognition that management development benefits from being problem and action based to ensure that the learning is appropriate to the context.

This has been used successfully in the health sector in middle-income and low-income countries.

However, there has been little research on its appropriateness and effects in these contexts, and its contribution to health workforce performance.

What are the new findings?

A management strengthening intervention (MSI) using an action research approach was tested in nine districts across three countries and was found to be an appropriate form of management strengthening for District Health Management Teams (DHMTs).

The MSI has positive effects on strengthening management and indicates strong potential for workforce performance improvement. The MSI is appropriate for other areas of health service management.

What do the new findings imply?

The MSI needs to be continued with existing participating DHMTs in order to reinforce and deepen their learning.

To have a significant impact on workforce performance and service delivery and ultimately on achieving UHC, the use of the MSI needs to be scaled up to cover many more districts in each country.

An extended version of Kirkpatrick’s four-level framework would help with the evaluation of this and similar MSIs.

Introduction

A major impediment to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and improve health outcomes is the lack of an adequate and well-performing health workforce.1–3 Many strategies are being used to expand the health workforce, but more attention should be devoted to the performance of the existing workforce. Based on the World Health Report 20064 and Vujicic and Zurn,5 we define workforce performance as ’the availability and distribution of staff and their effectiveness (including skills mix, levels of absence and quality and quantity of work output)’.6

Improving the effectiveness of the workforce requires an integrated set of relevant human resource management (HRM) strategies.7–9 In addition, to be effective these HRM strategies need to be integrated with other health system components and these strategies should be relevant to their context,10 such as level of managerial autonomy, resource availability and prevailing organisational culture.

Managers at district level, particularly in decentralised contexts, have some responsibility for the key health systems domains and are therefore well-placed to ensure an integrated approach to improving health workforce performance (HWP). While the importance of strengthening district health systems has long been recognised,11–13 insufficient attention has been paid to the area of HRM at this level and the competencies that enable district managers to effectively steer health service delivery at local level.14 15

The development of effective strategies to improve HWP requires both generic management and HRM competencies. Core management competencies include problem analysis, prioritisation, options appraisal, strategy development, resourcing, implementation and follow-up16; HRM competencies related to attracting and retaining staff to ensure availability, performance management and the integration of HRM strategies.17

While there has been much investment in the health sector in formal management training—although much less on HRM—for district level managers, action-based and problem-based learning has been favoured by a number of initiatives, particularly for planning and quality improvement.18–21 Much-needed research is being carried out to understand management challenges at district and subdistrict levels.3 22 23 The importance of empowerment to enable effective management has also been highlighted.24 However, few potentially scalable management development initiatives have been evaluated to provide much-needed lessons to support wider adoption.

The PERFORM project (2011–2015) aimed to explore appropriate ways of strengthening decentralised management to improve HWP in sub-Saharan Africa. Country research teams (CRT), who were members of the PERFORM project consortium, implemented a management strengthening intervention (MSI), described below, with District Health Management Teams (DHMT) in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda to understand the appropriateness and effects in various contexts. A full description of the approach is described by Mshelia et al.25

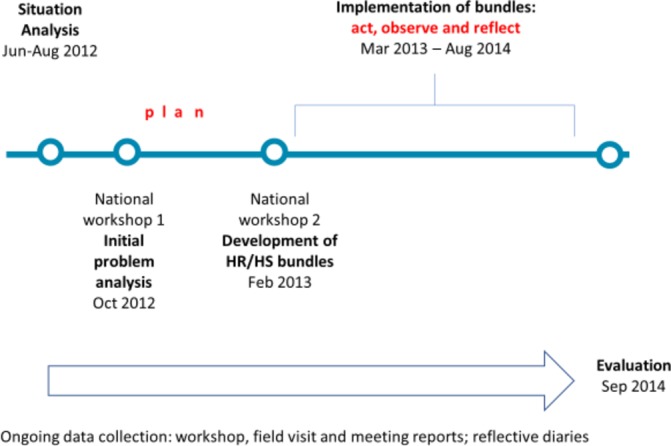

The intervention was based on the action research (AR) cycle entailing four stages: plan, act, observe and reflect.26 AR is manifested by the DHMTs in the following process: identify and plan strategies to address problems identified; implement strategies; observe and record the effects of the strategies and reflect on the processes and effects. The ‘reflection’ stage is key to learning and competency development.27 We also used a systems approach to address the workforce problems by ensuring that HR strategies to address the problem are integrated, that complementary health systems strategies are used and possible unintended effects on the health workforce or on other elements of the health system are analysed and monitored.

A generic design for the MSI was developed, with some variations in implementation at country level. The design addressed a simple competency framework, as mentioned by Armstrong16, which included the ability to analyse the root causes of health service delivery problems; prioritisation of problems; options appraisal; designing integrated HR and health systems strategies appropriate to context (resources, authority, feasibility, impact); resourcing (either from the regular budget or from external sources) and following through the implementation to overcome barriers (including developing plans with necessary and sufficient activities to support the objectives/strategies/outputs). Multiple and reinforcing methods used for developing these competencies included follow-on activities supported by the CRTs (table 1). Materials were developed for the project for each of the activities.28

Table 1.

Activities used for developing the competencies in the MSI framework and correspondence to the AR cycle

| DHMT management competencies | Development activities | Stages of AR cycle |

| Identification of root causes of problems | SA, NW1, NW2 | Plan |

| Prioritisation of problems | SA, NW1, NW2 | |

| Options appraisal | SA, NW2 | |

| Designing integrated HRM and health systems strategies appropriate to context | NW1—introduction only; NW2 | |

| Resourcing | NW2; follow-on activities | Plan/act |

| Implementing the workplan including monitoring and overcoming barriers | Follow-on activities (diaries, CRT visits and interdistrict meetings) | Act/observe/reflect |

CRT, country research teams; SA, situation analysis; NW1, national workshop 1; NW2, national workshop 2.

In the planning stage of the AR cycle, each DHMT, with support from the CRT, carried out a situation analysis (SA), which produced a list of problems. To support the objectives of the PERFORM project, these problems needed to include some aspect of workforce performance even if they addressed wider service delivery problems. The problems were refined before and during national workshop 1 (NW1), which was 1–1.5 days long. Root cause analysis was mostly done using the ‘but why’ technique29 30 and problem tree analysis31 and a short session for initial ideas on strategies for addressing the problems was included to stimulate thinking for the next stage of the process. An interval of about 3 months was provided which allowed the participants to report back to the full DHMTs, and other stakeholders, and to modify their problem analyses. National workshop 2 (NW2) was 2–2.5 days long and covered refining the problem analysis and developing workplans consisting of coherent HRM strategies and integration with complementary health systems strategies—what were referred to as ‘bundles of human resource/health systems (HR/HS) strategies’. The criteria used to help develop the workplans included: focus on improving HWP in the district; measurable and observable effect on workforce performance within 12–18 months; implementable within available resources in the district and linked to district plan and district priorities. Workplans developed at NW2 were incorporated into existing district annual plans or in some cases other funding was sought to ensure that they were sufficiently resourced. Districts were asked to send a selection of DHMT members to the workshops. Workshop attendance ranged from 17 to 31 with a good representation of DHMT members throughout the project. Not all DHMT members attended both workshops, but there was a sufficient critical mass who did. In Ghana and Tanzania, additional stakeholders—most from the regional offices—attended (table 2).

Table 2.

Participants by type attending the first two national workshops

| Country/districts and other stakeholders | National workshop 1 | National workshop 2 |

| Ghana | ||

| Kwahu West | 5 | 4 |

| Upper Manya Krobo | 5 | 4 |

| Akwapim North | 5 | 4 |

| Other stakeholders* | 5 | 6 |

| Totals | 20 | 18 |

| Tanzania | ||

| Mufindi | 8 | 8 |

| Iringa | 8 | 8 |

| Kilolo | 7 | 7 |

| Other stakeholders* | 8 | 5 |

| Totals | 31 | 28 |

| Uganda | 0 | |

| Kabarole | 4 | 13† |

| Jinja | 9† | 8 |

| Luwero | 4 | 9 |

| Other stakeholders | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 17 | 30 |

*Mostly regional staff.

†Host district, which explains greater attendance.

The strategies were then implemented by the DHMTs (the ‘act’ stage) and support was provided by the CRTs in the follow-on activities over a period of 18 months to support the ‘observe’ and ‘reflect’ stages of the AR cycle. These activities included guidance on using reflective diaries,32 visits to the districts by the CRTs and interdistrict meetings bringing all three DHMTs together to review progress and share experiences. A timeline for the intervention and data collection points is given in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline for the management strengthening intervention and data collection points.

This paper describes an evaluation of the MSI using Kirkpatrick’s four-level framework.33 This is a well-established framework for the evaluation of training, in spite of some criticism.34 35 It emphasises multiple (rather than single) measures of effectiveness and highlights the importance of transferring learning to behaviour change, and ultimately the impact on workforce performance and service delivery, although attribution and quantification becomes more challenging at this level. The focus of the evaluation is on the appropriateness of the MSI in decentralised contexts and its effects. The aim of the paper is to contribute to the limited body of empirical evidence available about the effectiveness of action-based MSIs in health systems in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). In addition, we aim to generate a set of lessons in this under-researched area that would support wider adoption of this approach to management strengthening to enable improved HWP management.

Methods

Study setting

In Tanzania and Uganda, health has been devolved to local government. The DHMT in Uganda and the Council Health Management Team (CHMT) in Tanzania report to and are resourced by a local government body. In Ghana, both devolution and delegation36 are in play and the DHMT reports both to the local government body and the Regional Health directorate.

Three districts were selected in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda for implementation of the MSI to enable interaction and learning between management teams. Criteria for district selection included first having a reasonably staffed district management team that was willing to participate; second a mix of urban and rural districts and third, with the exception of Tanzania, levels of performance based on national performance tables which use standard indicators from the District Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) such as average per capita use of health services or vaccination coverage (table 3).

Table 3.

Study districts by country and selection criteria

| Country/region | District | Location | Performance |

| Ghana | Akwapim North | Semi-urban | Average |

| Eastern region | Kwahu West | Rural | High |

| Upper Manya Krobo | Rural | Low | |

| Tanzania | Mufindi | Semi-urban | n/a |

| Iringa region | Iringa Urban | Urban | n/a |

| Kilolo | Rural | n/a | |

| Uganda | Kabarole | Rural | High |

| n/a | Jinja | Urban | High |

| Luwero | Rural | Average |

n/a, not available.

Study design

In order to address evaluation questions about the appropriateness of the MSI for the DHMTs and the effects of the management strengthening, we have employed the Kirkpatrick’s training evaluation framework.33 The model has four levels:

Reaction: the reaction of the participants to the programme content and delivery;

Learning: what the participants learnt;

Behaviour: changes in subsequent job performance through applying new competencies;

Results: effects at the level of the organisation as a result of the changes in job performance.

We generated evidence for each of these levels largely from interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted at the evaluation stage. Where possible, we have triangulated with data from documents. The evaluation used a range of documents produced during the project, and qualitative research methods to capture the views and experiences of the DHMTs at the end of the intervention.

Data collection methods

This paper draws on data from the methods used to observe and reflect on the implementation of the MSI, as well as the final evaluation of the intervention (figure 1).

Document review

Documents produced during the project implementation period (figure 1) were reviewed to identify evidence of the appropriateness of the MSI and the effect. These documents included: workshop reports which included participant feedback; problem trees and prioritisation lists; workplans developed and subsequently modified by DHMTs; DHMTs’ reflective diaries and progress reports on workplan implementation; reports of CRT follow-up visits and reports of the interdistrict meetings.

In-depth interviews and focus group discussions with DHMT members

DHMT members were purposively selected ensuring a range of participants covering gender, length of service and position in DHMT. The interviews, which took place during the evaluation (figure 1), explored the DHMT member’s detailed experiences and perceptions of the MSI and its effects. FGDs in Tanzania and Uganda were added to capture shared approaches to management and how the DHMT operated as a team. These included between 8 and 10 DHMT members. The interviews and discussions were conducted by the CRTs, took place in private areas within the district health offices. The in-depth interviews (IDIs) lasted between 30 and 60 min, whereas the FGDs were longer (from 60 to 120 min). They were digitally recorded. Table 4 gives a summary of the number of interviews and discussions conducted.

Table 4.

Summary of IDIs and FGDs with CHMT/DHMT members in each district by country

| Country | District | FGD | IDI |

| Ghana | Akwapim North | 0 | 4 |

| Kwahu West | 0 | 5 | |

| Upper Manya Krobo | 0 | 4 | |

| Tanzania | Mufindi | 1 | 8 |

| Iringa Urban | 1 | 8 | |

| Kilolo | 1 | 8 | |

| Uganda | Kabarole | 1 | 4 |

| Jinja | 1 | 5 | |

| Luwero | 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 6 | 50 |

CHMT, Council Health Management Team; DHMT, District Health Management Teams; FGD, focus group discussion; IDI, in-depth interview.

Analysis

A common coding framework was developed based on the questions relating to the MSI and effects on workforce performance and health service delivery and the data generated. This framework was applied to all data collected, including documents, using NVIVO software (V.10). The coded segments of data were then summarised and themes developed that compared and contrasted across the different study sites. Illustrative quotes from interviews, FGDs and documents were extracted and the findings presented under appropriate levels of the Kirkpatrick’s evaluation framework. Findings from each country were presented in a separate unpublished country report, which provided the source material for this paper.

Results

The results are presented in four sections in this paper, based on Kirkpatrick’s four levels for evaluating training33: reaction—which demonstrates that the management development intervention was seen as appropriate for the DHMTs; learning—which shows that DHMT members developed many of the core management competencies identified earlier; behaviour—which shows how both the management behaviour of individuals and the management team changed and produced other benefits for the team and results and results—which provides examples of how the MSI affected workforce performance and service delivery. As expected in a management development process that requires several MSI cycles to begin to show significant impact at the results level, this section is the least populated. Despite the diverse nature of the three countries, we found few differences in contextual factors that supported or limited the intervention.

Reaction: the process of developing management competencies

This section reports on the perceptions of the participants of the overall acceptability of the MSI including the support during the intervention period.

Acceptability of the overall process

The DHMT members from all three countries appreciated the way in which the MSI fitted in with their work commitments and staff were away from their districts for no more than 7 days in total. Even so, DHMT members could not always attend workshops and meetings. This was reported during interviews and FGD, as well as being observed during workshops and meetings.

Sometimes too, we divide ourselves so that some will go and others will stay and do the work. (DHMT member, Ghana)

There were comments from two countries about the fact that PERFORM brought no funds for the implementation of workplans: ‘whenever you talk of a project, it has a budget’ (DHMT member, Uganda). This may have been a source of frustration: ‘Lack of funds to implement PERFORM activities affected its implementation’ (DHMT Member, Ghana).

Despite this, the DHMTs eventually seemed to accept the conditions of the project and some even saw the absence of funds for interventions being made available through the project as having a positive benefit of focussing on smaller yet important problems.

Before PERFORM, people would not pay attention to these problems even the small ones, …… they would look for the big problems that require a lot of resources and yet, the small problems also impact on our performance. (DHMT member, Uganda).

Supporting the learning process

The facilitation process by the CRTs provided guidance and encouraged participation, thereby giving the DHMTs sufficient control of the process. All DHMTs reported that they could choose to address problems in their districts that were important to them.

they were more of facilitators of the discussion and actually we came up with what we thought was the best solutions to address these challenges and that in itself have made the interventions our own. (DHMT member, Uganda)

Bringing three districts together through joint national workshops and meeting in each country enabled the sharing of ideas and the peer-review process was appreciated and helped to improve the relevance of the strategies selected.

The initial problem was too broad, even for indicators it was difficult to tell where we were coming from and where we were going. It was not measurable. After the review process (by other CHMTs) we decided to revise the problem and strategies. (CHMT member, Tanzania)

An important benefit of the workshops and interdistrict meetings was to give DHMT members the protected time to work through some steps of the AR process by taking people away from office.

Hindering the learning process

While staff turnover did not cause problems in other countries, frequent changes of leadership in one CHMT in Tanzania created a lack of continuity and weakened the gradual development of leadership skills.

Learning: the development of management competencies

This section reports on the development of the management competencies described in table 1.

Problem analysis

Many DHMT members in all three countries reported being familiar with the general process of problem analysis, which they had learnt from training or other development projects and recognised the benefits. What stands out is the impact that the more thorough approach to problem-solving using root cause analysis had on the participants: ‘(we identified) gaps that were not obvious to us at the time’ (DHMT member, Uganda) and the importance of techniques like the use of problem trees for root cause analysis.

If you do not do the problem tree analysis, you will be doing things randomly without any specific objectives in mind. (CHMT member, Tanzania)

The participants found understanding the causal linkages in the problem analysis helpful: ‘It was very good and important for the team to get a logical flow of the problem trees’ (participant feedback in Report of National Workshop 2, Uganda).

The progression through the SA, NW1 and NW2 produced, in many cases, a much deeper analysis of the problems and therefore a better plan to address them. The workshop reports in Ghana demonstrate an example of this. The problem identified by the DHMT from Akwapim North (Ghana) in NW1 was ‘Poor staff performance in EPI (expanded programme for immunisation)’ and their initial response was to ‘provide refresher training on monitoring and supervision’. Further analysis of the problem by the time of NW2 produced the following more elaborate problem statement: ‘High dropout rate (40%) in EPI performance on the new vaccines (ROTA and pneumococcal) for the first half year of 2012’.

The DHMTs were able to assign priorities to their lists of problems:

Yes, …. when you are able to identify problems, when you are able to analyse the cause of the problems, … it gives you where to put your money… (DHMT member, Uganda)

Designing integrated HRM and health systems strategies appropriate to context

All DHMTs learnt about the importance of using criteria for selecting strategies which included feasibility, effectiveness, affordability within available resources and synergies with other interventions in the district. This facilitated the options appraisal step. Tanzania and Uganda DHMTs emphasised the important link between problem analysis and the development of more relevant strategies.

We came up with a number of areas…. they were also system problems which can be addressed by the DHMT without an extra cost. Then we developed workable solutions within our reach to address. (DHMT member, Uganda)

Participants acknowledged that they found the process of developing an integrated set (or ‘bundle’) of HR and health systems strategies and appropriate indicators somewhat challenging. Putting the theory into practice is not so easy:

The strategies to choose, actually as we were with the research country team they taught us the bundles, how to make bundles. However, when we are seated there (in the workshop) because of the many issues to discuss you may fail to make bundles and you just choose randomly. (DHMT member, Uganda).

Nevertheless, most of the workplans produced by the DHMTs demonstrated some complementarity of HRM and health systems strategies. The example in table 5 shows a mixture of complementary HRM strategies and activities (improved supervision and reward mechanism) with complementary health systems strategies (improved data management) to address the problem of poor implementation of the vaccine schedule. While the Ugandan DHMTs focused directly on the health workforce problems, DHMTs in the other two countries started with service delivery problems. The problems identified and strategies developed to address them given for all DHMTs in Attachment 1.

Table 5.

Example of integrated bundle of HRM and health systems strategies from Kwahu West district, Ghana

| Problem identified | HR/HS strategies to address the problem | Activities |

| Poor implementation of new vaccine schedule leading to high dropout rate of pneumococcal (46.9%) and rotatix (19.1%) vaccination in the municipality | Improve data management at all levels Improve supportive supervision to subdistrict Reward (certificate and material) best performing facilities (drop rate of PCV and ROTA 10% and below) |

Train and retrain all staff on new vaccine |

| Conduct monthly data validation per facility by comparing tally books | ||

| Enforce use of separate log books for drop-in and drop-out | ||

| Train all staff in logistics management | ||

| Obtain standard EPI supportive supervision checklist from DDPH/RHA | ||

| Input from subdistrict staff effected and final checklists circulated to all facilities | ||

| On-site supportive supervision in general but EPI in particular (two visits per facility per year) | ||

| Hold quarterly meetings to review performance and share best practices Award prize to best performing health facilities |

DDPH, Deputy Director of Public Health; EPI, Expanded Programme for Immunisation; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; RHA, Regional Health Administration.

All DHMTs developed indicators for their workplans, although only DHMTs in Ghana and one CHMT in Tanzania developed specific targets and used these to track effects of the strategies. Some DHMTs found it difficult to identify useful indicators:

Although the CHMT was able to formulate the bundles, the CHMT faced difficulties in determining and formulating measurable indicators (Country Report, Tanzania).

Over time, DHMTs recognised the importance of developing indicators for which data could easily be collected as a way of measuring the impact of the strategies.

Resourcing

Little specific guidance was given in the workshop on this competence. The assumption was that given the advice on selecting affordable strategies mentioned above, teams would be able to identify appropriate resources for implementation. Some DHMTs were able to verify budget lines for proposed activities during the workshops. Some teams realised that the headings in their budgets were sufficiently broad to cover these activities in their workplans, for example, in Uganda, there were existing budget lines for supervision and appraisal and so the DHMTs were able to use these resources to support their workplan. In other cases, where this was not possible or funds from the regular budget were delayed, in particular in Tanzania, they either reprogrammed activities for the next budget cycle or successfully approached agencies working locally for funds. Ghana DHMTs integrated some PERFORM activities with donor funded project activities, for example, supervision and used one programme to subsidise another.

For example, there are no allocation of funds for EPI supervision, so if malaria control program makes funds available for malaria monitoring, we try to integrate EPI supervision into it but make sure it doesn’t interfere with the main program. (DHMT Member, Ghana)

Implementing the workplan including monitoring and overcoming barriers

In all three countries, the challenge of implementing plans in the real world was felt when participants returned to their district after NW2. This sometimes revealed weaknesses at the planning stage.

These workplans are easy to make but the only problem comes in the implementation; now take an example here in Luwero, we have a problem of transport so …. when it comes to implement (the workplan) that is where the problem comes in. (DHMT member, Uganda)

DHMTs in Ghana and Uganda reported that implementation of the workplans was in competition with other activities or frequent and impromptu training and workshops.

The other issues were competing activities. You find you have planned an activity, another activity comes on and you find there is conflict of interest and you find that the activity is not implemented as earlier scheduled. (DHMT member, Uganda)

Nevertheless, workplans did get implemented through the development of relevant systems. For example, in Uganda, one district management team developed a tool for tracking absenteeism (a simple attendance register) and formed a disciplinary committee to deal with offenders. The tracking tool was being used:

arrival books have been put in place and … every health worker who is supposed to be on duty is at least registering in that book as an evidence that at least health workers are at work. (DHMT member, Uganda)

To support the implementation of the full AR cycle, DHMTs were encouraged to reflect on progress with implementation of the workplans including using reflective diaries. All nine district teams kept diaries to monitor progress and challenges of implementation, as well as effectiveness of the strategies. They formed the basis for reflection during team meetings. DHMTs in Ghana reported that they were time-consuming to maintain. Uganda found the logistics of ensuring all DHMT members had access to the diary challenging. In Tanzania, the CHMTs appointed a focal point to manage the diary. In spite of the challenges, there was evidence that the diaries were used for both documentation and reflection on implementation progress and effectiveness of the strategies. As a result of this reflection by the DHMTs, some plans were modified. For example, the use of the Local Health Management Committee in one district in Ghana to monitor attendance of the Community Health Officers proved contentious, so this role was reallocated to district and regional level administration. In Uganda, one DHMT reflected on the process of conducting appraisals:

the majority (of staff) are really being appraised. But I think the standard of appraisals is still wanting. We still need to improve on the ability to handle those appraisal forms so that they really bring out exactly what we want. (DHMT member, Uganda)

Behaviour: effects on the functioning of the DHMT as managers

In addition to the management competencies strengthened by the MSI, there is evidence of a change in the way in which the DHMTs functioned. This included ownership and empowerment, initiative taking or entrepreneurial approach, team work and collaboration and application of learning to other areas.

Empowerment

We have taken empowerment to mean ‘the ability of people with organisations to use their own initiative to further organisational interests’37 p. 83 and the effect of empowerment through AR as shifting ‘power towards those affected by the problem’.38 p. 14 The process of selecting priority problems, analysing them and developing and implementing strategies provided this sense of empowerment and ownership for the DHMTs:

we can push for change (DHMT member, Tanzania)

We also wanted to have ownership on whatever we do, and we think we are getting there. (DHMT member, Uganda)

By being able to analyse potential challenges in implementing strategies, the DHMT felt able to find solutions using existing:

the PERFORM approach helps us to identify possible challenges we may face at the implementation stage and a possible solution. It also helps us to identify our available resources and capacity (DHMT member, Ghana)

Empowerment was also derived from actively monitoring the implementation of their plans, as one CHMT member in Tanzania reported:

Yesterday, I was presenting a report to the RMO’s meeting and I found myself so confident because I had all the necessary data as evidence to support my presentation which I learned to track and record through the diary by PERFORM people. (CHMT member, Tanzania)

Entrepreneurial approach

Increased empowerment may be manifested in a more ‘entrepreneurial approach’39 to management, as shown by a number of DHMTs. In Tanzania and Uganda, the DHMTs reported working more with NGOs in the districts to secure funds for their strategies.

TUNAJALI (HIV/AIDs NGO) were involved in a budget meeting and Unicef, TUNAJALI and politicians were involved to make decisions during allocation of resources in the district. (Tanzania, country report)

There were some problems that we identified that were not actually in our district plan. So we said what can we do about these? We did not stop there but we designed solutions. One of them was to look around for the partners (Baylor, BTC, Uganda Capacity Program) that are within the area and share with them which one of these can they handle. (DHMT member, Uganda)

One Ugandan DHMT showed initiative and creative thinking in searching for funding for orientation of newly recruited staff. Other DHMTs in Uganda were encouraged by the success of this strategy to explore links with the private sector.

The newly recruited health workers have already been inducted into their roles and responsibilities with financial support sent from the Housing Finance Bank (Uganda) Limited. (Report of CRT visit to the DHMT Kabarole District)

Team working and collaboration

Perhaps the most noticeable impact the process had on the operation of the DHMTs in all settings was the stimulation of greater collaboration and teamwork both within DHMTs, including those who were not able to attend the workshops, and with other district teams:

It has united us so much. PERFORM has made us do so many activities as a team. You may find that a pharmacist works together with a laboratory technician, and you do the same with a doctor. It has helped to bring people together and foster a common understanding of many things. (CHMT member, Tanzania)

The DHMT members appreciated the opportunity this approach had given them to discuss problems in detail and have everybody bring his/her thoughts on board. (Ghana national workshop 2 report, February 2013)

Application to other areas of work

An unintended effect of the MSI was that DHMTs saw the possibility of applying the lessons learnt in developing strategies to improve HWP to other areas of their work.

Participants kept acknowledging PERFORM project for either wakening them up to reflect on critical issues and areas that compromised health worker performance in their individual districts or PERFORM project introducing a unique methodology of addressing human resource issues and/or that could be extended to other health system interventions. (Interdistrict workshop 2 report, Uganda)

Results: impact on workforce strengthening and service delivery

This section reports on independently verifiable results, perceived results and additional unintended consequences as reported by the DHMTs. Akwapim North and Kwahu West districts in Ghana were able to demonstrate improvements in the vaccination programme as a result of their workplans. By improving the quality of supervision by Community Health Officers, record keeping and defaulter tracing improved.

The EPI activities help us to do follow-up to know when a patient is due for a vaccine… we visit them at their sites regularly to look through their books. This sometimes makes some facilities not to have defaulters. (DHMT member, Ghana)

From their review of HMIS data, the DHMT concluded that their strategies are likely to have contributed to the increased vaccination coverage and reduced dropout rates. Akwapim North district reported that it had reduced client dropout for pneumococcal vaccination from 38% in 2012 to 0% in 2014 when the MSI finished. Similar verifiable improvements due to improved data management and supervision were identified by Kwahu West DHMT.

Some DHMTs were unable to use independently verifiable data, but perceived that their workplans had led to improvements. For example, in Tanzania the CHMT in Mufindi perceived that demand for HIV services had increased and more drugs were available. In Uganda, Jinja DHMT, which identified HRM as being weak, perceived that the appraisal process had improved and more staff were being appraised.

DHMTs also reported unintended effects of their workplans—both negative and positive. As might be expected when the focus of work is on one area, this leads to neglect in other area. For example, the focus on antenatal care services in Upper Manya Krobo was perceived to detract from the routine services provided by Community Health Officers. In Mufindi district, increased demand for HIV services to address the problem of high prevalence in the district led to shortages of drugs and equipment. Examples of positive unintended consequences of the workplans included more interaction between the DHMT and facility managers (Upper Manya Krobo, Ghana); the problem-solving approach being adopted by the district council (Mufindi, Tanzania) and non-participating DHMTs visiting Kabarole DHMT (Uganda) to learn about their problem-solving approach.

More details on the results of all the DHMTs workplans are given in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjgh-2017-000619supp001.pdf (264.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

This study provides a unique contribution to the literature in management strengthening in the health sector in middle-income and low-income countries. It tested an action researchbased MSI in nine districts across three countries. We report similar positive messages about the appropriateness and effects to that of much earlier single country interventions in Tanzania and the Gambia.29 40 This section uses Kirkpatrick’s framework to identify lessons at different evaluation levels.

With respect to the REACTION level, the reports were mostly positive. The process was not seen as disruptive, an important factor found with another MSI in Zambia,41 which may reflect the design of having a mixture of very short workshops, 1 day meetings and follow-up visits. This is fortunate, as bringing together what Revans refers to as ‘comrades in adversity’42 through the workshops and interdistrict meetings, is important for learning and shaping how the teams work back in their districts.41. While there was praise for the facilitation skills in the PERFORM project, the risk of poor processes of selection and development of facilitators has been identified when similar initiatives are scaled-up43; these processes would not be captured in Kirkpatrick’s framework. A key concern in the design of PERFORM was to develop a sustainable MSI that could continue after the end of the project. Therefore, we decided that unlike some of the earlier models of action-research-based management strengthening,40 43 the project would not provide implementation funds for the plans developed by the DHMTs. This was perceived to be a risk and was carefully addressed in the briefings of DHMTs before they agreed to participate.44 Although there were initial concerns at the lack of funding, some DHMTs saw the positive side of learning to make better use of available resources or adopt a more entrepreneurial attitude with local resource mobilisation. In contexts where external ‘projects’ are assumed to bring additional funding, this approach may not work so well and therefore jeopardise the sustainability of the MSI. A proper assessment of the context is needed before introducing this kind of MSI to ensure sustainability, although more guidance, based on political economy analysis,45 on key features of a supportive context need to be developed.

At the LEARNING level, there was stronger evidence of improvement in management competencies at the ‘plan’ stage of the AR cycle, which mostly took place in the two workshops (figure 1). The general process of problem analysis and developing plans appeared to be familiar to most participants, although they recognised the importance of carrying this out in more depth and focussing on the right questions. The time devoted to developing workplans to address the problems identified was quite short and involvement of other stakeholders quite limited. Nevertheless, although with more time and consultation the workplans could have been more sophisticated, the strategies the DHMTs developed were largely complementary and appropriate to the need, which Marchal and Kegels suggest is more important than the exact composition of the bundle46 and, with the all-important (but challenging to research) reflection component of the AR cycle,3 provides the opportunity for learning. Although some DHMTs added budgets to the workplans in the workshops, real learning about resourcing took place at the implementation stage. Most DHMTs found ways of funding their plans including creative use of the current budget, deferring activities to the next financial year or using partnerships to fund activities, although in Tanzania this appeared to be more challenging and might have affected their ability to learn through action.

While the list of competencies is quite short in comparison with formal management training courses, the learning was based on analysing and addressing real problems that the DHMTs faced and is likely to deepen—for example, regarding the importance of setting and monitoring indicators—as subsequent MSI cycles are undertaken. Stakeholders responsible for determining the future of such MSIs should be made aware of the trade-offs between breadth and depth of MSIs.

At the BEHAVIOUR level, various changes about the way in which the DHMT functioned were identified by respondents, but could also have been affected by other interventions. Bringing people together as teams can help to increase collaboration and build trust. In a similar initiative in Tanzania many years earlier the DHMTs had reportedly ‘established an identity, and confidence to act’.43 The DHMTs in the PERFORM project felt more empowered and demonstrated more entrepreneurial spirit. They had the opportunity to explore their ‘decision space’, which is also necessary to support effective use of decentralisation policy.47 In Ghana and Tanzania, the regional and provincial levels respectively were involved in the project (table 2) and provided an important level of support that would be needed in other projects. There is no middle tier in Uganda, but for future programmes higher level support will be needed.

A health management mentoring programme in Mozambique found that the management domain of monitoring and evaluation showed the least overall improvement.48 It was also initially difficult to garner much interest for developing indicators for the action plans developed by the DHMTs in PERFORM. However, once they saw the need to monitor plans designed to address problems that they themselves had identified, as reported in the Gambia,40 they became more interested. Patience is needed on the part of facilitators not to judge behaviour too quickly, as the process will support learning if allowed.

The combination of empowerment, adoption of a more entrepreneurial approach and better team working and collaboration may create a district management team better able to respond to and address local challenges. One result of an intervention in a large hospital in Ghana which addressed issues of participation, involvement and empowerment was the development of a positive organisational climate.49 This behaviour change is unlikely to be achieved using conventional management development initiatives. Continuous use of the MSI is needed to sustain this change.

At the RESULTS level, particular caution is needed with regard to attribution especially in contexts characterised by multiple programmes and initiatives and ideally externally verifiable data are needed. Because of the nature of the problems and indicators selected and availability of the HMIS, this was possible for two DHMTs in Ghana. This provides strong justification for the use of the MSI.

The focus of PERFORM was on workforce performance to complement initiatives to increase the quantity of health workers.50 The root cause for most of the workforce performance-related problems identified was—as is often the case9—either the poor or inappropriate operation of existing HRM systems (eg, appraisal) or the lack of an appropriate system (eg, for tracking staff absence). At the time of the evaluation, the information available was on the extent to which the systems had been implemented, for example, the use of attendance registers. For reasons related to the use of indicators for the workplans as described above, no hard data on the change in levels of absence following the use of the register were available; the evaluation was based on verbal reports and perceptions. It is expected that, where DHMTs have recognised the importance of more careful monitoring, evaluation would improve in subsequent MSI cycles. Nevertheless, the reporting of assumed impact on service delivery demonstrates useful evidence of thinking in terms of a theory of change linking, for example, improved supervision to increased vaccination coverage. After all, this is what the DHMT is held accountable for, particularly in decentralised contexts, and if they can see the link between improved workforce performance and improved service delivery then this will provide the encouragement needed to address workforce performance issues.

The evaluation of the PERFORM MSI provides a few key lessons for the use of similar interventions, as shown in table 6.

Table 6.

Key lesson for the planning and implementation of management strengthening interventions (MSI)

| MSI phase | Lesson |

| Planning | 1. An assessment of the perception of externally funded projects and the expectation of additional funding is needed to decide on the suitability and sustainability of the MSI |

| 2. The MSI needs to be planned as a series of ongoing cycles to support continued learning | |

| 3. In some settings, support for the MSI is needed at higher levels than the district, such as the region or province | |

| 4. Stakeholder expectations need to be managed regarding outcomes of the MSI: developing better management skills will be gradual and motivation for key aspects of management (eg, M&E) may take time to develop; the benefits may include change in organisational climate and effectiveness of the District Health Management Teams | |

| Implementation | 5. Care in the selection and training of facilitators is needed to ensure that MSI is faithfully implemented |

| 6. Sufficient time is needed for a thorough problem analysis before developing strategies to address them | |

| 7. The focus should be more on developing complementary strategies, which are appropriate to the task rather than the exact composition of the bundles |

A limitation of this study was the lack of independence of the evaluation process, which was carried out by the CRTs, although the use of multiple methods to triangulate findings and cross-checking by different consortium partners helped to reduce bias. The Kirkpatrick’s framework is helpful in evaluating the effects of the MSI at different stages of the logic model that links the intervention to the goal of improving health service delivery. While levels 1 and 2 of the framework are frequently used in training evaluation, the use of Kirkpatrick’s level 3 (behaviour) and level 4 (results or outcome) is notoriously difficult,35 partly because of access to the participants after the training and for reasons of attribution and the availability of externally validated data. Measurement of change at this level is a limitation for other management development interventions,41 although there is a tension between the ‘extractive process’ used by external researchers for evaluation purposes and the collaborative approach which supports learning.3 In the PERFORM MSI, the contact with the participants is maintained through the implementation stage. In addition, as participants increasingly appreciate the importance of the use of monitoring and evaluation of their workplan, evaluation at level 4 becomes easier and more collaborative. Because of the crucial nature of the initial stage of the logic chain, to ensure ‘implementation fidelity’,51 it is not enough to rely on participants’ reaction, as many action-based learning approaches have been diluted and misused.52 Phillips identifies a fifth level of evaluation to include return on investment.53 At a minimum, a basic costing exercise should be carried out to help decision-makers determine the value of using the MSI. So, while Kirkpatrick’s framework has helped our evaluation of the PERFORM MSI, some additional levels would make it more suitable.

Conclusions

Action-based learning has been used quite extensively in the health sector to strengthen management, yet there has been little evidence of its appropriateness and effects. We have demonstrated, using Kirkpatrick’s levels of evaluation, that our management strengthening approach was acceptable and has strengthened the competencies of the DHMTs to improve HWP and service delivery. We have provided specific lessons to help other agencies implementing similar MSIs. However, perhaps the most important points to emphasise are: the MSI needs to be continued with existing participating DHMTs in order to reinforce and deepen their learning; and to have a significant impact on workforce performance and service delivery, the MSI needs to be implemented in many more districts in each country. The programme is now being scaled up in Ghana and Uganda and initiated with a view to scale-up in Malawi under the PERFORM2scale project (www.perform2scale.org). More lessons will be identified from the new project about effectively managing the scale-up process to ensure the use of the MSI is sustainable at national level. Only then will the use of the MSI really begin to make a major contribution to achieving UHC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the officials in the ministries of health, regional and provincial offices, local government and DHMTs in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda – with whom we learnt much about management strengthening and health workforce performance challenges. The project involved a consortium of six partners: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, University of Leeds, University of Ghana, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Institute of Development Studies, University of Dar-es-Salaam, School of Public Health, Makerere University. The authors would also like to thank the research teams from these institutions who made this study possible.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: All authors were involved in conceptualising this paper. All authors were involved in the design and implementation of the project and the data collection and analysis for the evaluation. TM and JR drafted the paper. All authors reviewed and provided critical inputs to the drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This document is an output from the PERFORM project: improving health workforce performance in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda, funded by the European Commission’s Seventh Framework programme (FP7 Theme Health: 2010.3.4-1, grant agreement number 266 334). The project involved a consortium of six partners: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, University of Leeds, University of Ghana, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Institute of Development Studies, University of Dar-es-Salaam, School of Public Health, Makerere University.

Disclaimer: The views expressed and information contained in the article are not necessarily those of or endorsed by the EC, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK (reference number 12.09); Makerere University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee, Uganda; National Institute for Medical Research, Tanzania; Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Sousa A, Scheffler RM, Nyoni J, et al. A comprehensive health labour market framework for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:892–4. 10.2471/BLT.13.118927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cometto G, Campbell J. Investing in human resources for health: beyond health outcomes. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:51 10.1186/s12960-016-0147-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lehmann U, Gilson L. Action learning for health system governance: the reward and challenge of co-production. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:957–63. 10.1093/heapol/czu097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO. World health report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vujicic M, Zurn P. The dynamics of the health labour market. Int J Health Plann Manage 2006;21:101–15. 10.1002/hpm.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. PERFORM Consortium. District health management team methods manual. UK: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. e Cunha RC, e Cunha MP. Impact of strategy, strength of the HRM system and HRM bundles on organizational performance. Problems and Perspectives in Management 2009;7:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Macduffie JP. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. ILR Review 1995;48:197–221. 10.1177/001979399504800201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchan J. What difference does ("good") HRM make? Hum Resour Health 2004;2:6 10.1186/1478-4491-2-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Savigny D, Adam T. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chatora R, Tumusiime P. Module 1: health sector reform and district health systems. Dist. Heal. Manag. Team Train. Modul. Brazzaville: World Health Organisation, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meessen B, Malanda B. Community of Practice “Health Service Delivery”. No universal health coverage without strong local health systems. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:78–78A. 10.2471/BLT.14.135228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. Report of the interregional meeting on strengthening health systems based on primary health care. Harare, Zimbabwe, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradley EH, Taylor LA, Cuellar CJ. Management matters: a leverage point for health systems strengthening in global health. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:411–5. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu X, Martineau T, Chen L, et al. Does decentralisation improve human resource management in the health sector? A case study from China. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1836–45. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Armstrong M. Managing activities. London: Institute of Personnel and Development, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armstrong M, Taylor S. Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice: Kogan Page Publishers, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dieleman M, Gerretsen B, van der Wilt GJ. Human resource management interventions to improve health workers' performance in low and middle income countries: a realist review. Health Res Policy Syst 2009;7:7 10.1186/1478-4505-7-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eggar D, Ollier E, Tumusiime P, et al. Working paper 11: strengthening management in low-income countries: lessons from uganda a case study on management of health services delivery. Geneva: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwamie A, van Dijk H, Agyepong IA. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: realist evaluation of the leadership development programme for district manager decision-making in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:29 10.1186/1478-4505-12-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Daire J, Gilson L, Cleary S. Developing leadership and management competencies in low and middle-income country health systems: a review of the literature : RESYST. London, UK: LSHTM, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilson L, Barasa E, Nxumalo N, et al. Everyday resilience in district health systems: emerging insights from the front lines in Kenya and South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000224 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nzinga J, Mbaabu L, English M. Service delivery in Kenyan district hospitals - what can we learn from literature on mid-level managers? Hum Resour Health 2013;11:10 10.1186/1478-4491-11-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tetui M, Coe AB, Hurtig AK, et al. A participatory action research approach to strengthening health managers' capacity at district level in Eastern Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:110 10.1186/s12961-017-0273-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mshelia C, Huss R, Mirzoev T, et al. Can action research strengthen district health management and improve health workforce performance? A research protocol. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003625 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reason P, Bradbury H. The Sage handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. 2nd edn London, Calif, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schön D. The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28. PERFORM project. Action research toolkit. http://performconsortium.com/action-research-toolkit/ (accessed 01 Jul 2017).

- 29. Barnett E, Abbatt F. District action research and education: a resource book for problem solving in health systems. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cassels A, Janovsky K. Strengthening health management in districts and provinces. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31. DFID. Tools for development: a handbook for those engaged in development activity (version 15.1): DFID, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mshelia C, Lê G, Mirzoev T, et al. Developing learning diaries for action research on healthcare management in Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda. Action Res 2016;14:412–34. 10.1177/1476750315626780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. 2nd edn San Francisco, Calif: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bates R. A critical analysis of evaluation practice: the Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Eval Program Plann 2004;27:341–7. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reio TG, Rocco TS, Smith DH, et al. A critique of kirkpatrick’s evaluation model. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 2017;29:35–53. 10.1002/nha3.20178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheema GS, Rondinelli DA. Decentralization and development: policy implementation in developing countries: Sage Publications, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lloyd P, Braithwaite J, Southon G. Empowerment and the performance of health services. J Manag Med 1999;13:83–94. 10.1108/02689239910263163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loewenson R. Participatory action research in health systems. A methods reader. Harare: EQUINET, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hales C. Leading horses to water? The impact of decentralization on managerial behaviour. Journal of Management Studies 1999;36:831–51. 10.1111/1467-6486.00160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conn CP, Jenkins P, Touray SO. Strengthening health management: experience of district teams in The Gambia. Health Policy Plan 1996;11:64–71. 10.1093/heapol/11.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mutale W, Vardoy-Mutale AT, Kachemba A, et al. Leadership and management training as a catalyst to health system strengthening in low-income settings: Evidence from implementation of the Zambia Management and Leadership course for district health managers in Zambia. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174536 10.1371/journal.pone.0174536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Revans RW. The origins and growth of action learning. Bromley: Chartwell-Bratt, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnett E, Ndeki S. Action-based learning to improve district management: a case study from Tanzania. Int J Health Plann Manage 1992;7:299–308. 10.1002/hpm.4740070406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. PERFORM. Tips on how to facilitate an introductory meeting with District Health Management Teams Undated. http://performconsortium.com/media/1058/tips-for-introductory-meeting.pdf (accessed 13 Oct 2017).

- 45. Harris D. Applied political economy analysis a problem-driven framework. London: ODI, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marchal B, Kegels G. Focusing on the software of managing health workers: what can we learn from high commitment management practices? Int J Health Plann Manage 2008;23:299–311. 10.1002/hpm.882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bossert TJ, Mitchell AD, Janjua MA. Improving health system performance in a decentralized health system: capacity building in Pakistan. Health Systems & Reform 2015;1:276–84. 10.1080/23288604.2015.1056330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Edwards LJ, Moisés A, Nzaramba M, et al. Implementation of a health management mentoring program: year-1 evaluation of its impact on health system strengthening in Zambézia Province, Mozambique. Int J Health Policy Manag;4:353–61. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marchal B, Dedzo M, Kegels G. Turning around an ailing district hospital: a realist evaluation of strategic changes at Ho Municipal Hospital (Ghana). BMC Public Health 2010;10:787 10.1186/1471-2458-10-787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Crisp N, Gawanas B, Sharp I. Training the health workforce: scaling up, saving lives. Lancet 2008;371:689–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60309-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Patterson M, Rick J, Wood S, et al. Systematic review of the links between human resource management practices and performance. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1-334, iv 10.3310/hta14510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Revans R. ABC of action learning. Bromley, UK: Chartwell-Bratt Ltd, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Phillips JJ. Measuring the return on investment: key issues and trends. 2nd edn Burlington, MA: Butterworth Heinemann, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2017-000619supp001.pdf (264.1KB, pdf)