Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the removal of nitrate from synthetic groundwater by a cathode followed by an anode electrode sequence in the electrochemical flow-through reactor. We also tested the feasibility of the used electrode sequence to minimize the production of ammonia during the nitrate reduction. The performance of monometallic Fe, Cu, Ni and carbon foam cathodes was tested under different current intensities, flow rates/regimes and the presence of Pd and Ag catalyst coating. With the use of monometallic Fe and an increase in current intensity from 60 mA to 120 mA, the nitrate removal rate increased from 7.6% to 25.0%, but values above 120 mA caused a decrease in removal due to excessive gas formation at the electrodes. Among tested materials, monometallic Fe foam cathode showed the highest nitrates removal rate and increased significantly in the presence of Pd catalyst: from 25.0% to 39.8%. Further, the circulation under 3 mL min−1 elevated the nitrate removal by 33% and the final nitrate concentration fell below the maximum contaminant level of 10 mg L−1 nitrate–nitrogen (NO3-N). During the treatment, the yield of ammonia production after the cathode was 92±4% while after the anode (Ti/IrO2/Ta2O5), the amount of ammonia significantly declined to 50%. The results proved that flow-through, undivided electrochemical systems can be used to remove nitrate from groundwater with the possibility of simultaneously controlling the generation of ammonia.

Keywords: electrochemical, nitrates, ammonia, groundwater, cathode

1. Introduction

Nitrates are commonly found in groundwater at high levels due to intensive contamination from nitrogen fertilizers, industrial wastes, animal wastes and septic systems, and they present a significant environmental problem (Hatfield et al. 2008). Higher levels of nitrates are found in private wells than in public water systems, in shallow wells (<100 feet below land surface) than in deep wells, and in agricultural areas than in urban areas. A considerable number of people, about 16% of the U.S. population, use private, unregulated water systems that are usually located in areas considered more vulnerable to nitrates contamination, such as rural regions.

Some reports have suggested an association between exposure to nitrates in drinking water and spontaneous abortions, intrauterine growth restriction, sudden infant death syndrome (George et al. 2001) and various birth defects. Excess levels of nitrates are proven to cause methemoglobinemia, or “blue baby” disease. On the basis of methemoglobinemia cases reported to the American Public Health Association, the maximum contaminant level (MCL) for nitrates in drinking water was set at 10 mg L−1 nitrate–nitrogen (NO3–N) or 45 mg L−1 nitrate (NO3−).

The best available technologies (BAT) for treatment of nitrate-contaminated water include reverse osmosis, electro-dialysis and ion exchange (Raymond Becker and Mills 2013). However, the utility of these processes has been limited due to their expensive operation and the subsequent problem of disposing the generated nitrate waste brine. The alternatives to BAT that have a potential to be used in situ are biological denitrification (BD), chemical reduction (CR) and physical adsorption (PA) (Della Rocca et al. 2007). Among these, chemical reduction of nitrates by using hydrogen over a solid catalyst, offers an alternative and economically advantageous process to biological removal of nitrate from water (Hörold et al. 1993). Nitrate was found to be hydrogenated only by bimetallic, preferably Pd-Cu, catalysts, whereas nitrite and its intermediates can be reduced with a monometallic, preferably Pd, catalyst. With hydrogen as the reductant, nitrate is converted to nitrogen as a main product and ammonium as by-product. However, CR faces challenges in reduction selectivity towards nitrogen gas production, the need for implementing the hydrogen injection devices and the high cost of the noble metal catalysts for an in situ application.

Studies have shown that the efficiency and selectivity of nitrate hydrogenation (chemical and electrochemical) are influenced by the type of catalysts, catalyst support, pH, hydrogen flow and metals ratio in bimetallic electrodes (Pintar et al. 1998; Pintar 1999; Prüsse et al. 2000; Epron et al. 2001; Prüsse and Vorlop 2001; Liou et al. 2009; Ding et al. 2015). Monometallic Pd catalysts exhibit no activity for nitrate reduction: nitrates do not adsorb on monometallic Pd sites. So, for nitrates reduction a second metal is needed (Prüsse and Vorlop 2001). It was found that the nitrates reduction activity and selectivity are determined by bimetallic ensembles containing Pd with Cu or Sn as promoters, at which the nitrates are adsorbed (Prüsse and Vorlop 2001). Further, nitrates are reduced to nitrites by hydrogen, which is supposed to spill over from Pd sites to the bimetallic sites (Prüsse et al. 2000). The promoting effect of the second metal can be related to its redox properties, confirming that nitrate reduction occurs through a bifunctional mechanism following: (a) a direct redox mechanism between promoter and nitrate, and (b) a catalytic reaction between hydrogen, chemisorbed on the noble metal, and intermediate nitrite. The reduction of nitrites and other byproducts can occur via support of monometallic catalysts (Prüsse et al. 2000).

An alternative approach for nitrate reduction that could be feasible for an in situ application is electrochemical reduction, which allows in situ generation of hydrogen at the cathode via water electrolysis, the possibility of using catalysts in small amounts (as cathode coating) and low energy consumption if alternative power sources are used (e.g. solar power). The electrochemical reduction has been investigated for nitrates removal from aqueous solutions (de Vooys et al. 2000; Wang and Qu 2006; Li et al. 2010; Ding et al. 2015; Govindan et al. 2015).

Similarly to the bimetallic catalyst mentioned above, a Cu-modified Pd electrode showed a higher capacity of nitrate reduction than a monometallic Pd electrode (de Vooys et al. 2000). However, the use of expensive bulk Pt and Pd is a disadvantage from a practical viewpoint. To address this challenge, the cost-effective materials such as graphite, Ni and Fe were used as cathodes and showed promising results for nitrate removal and selectivity towards nitrogen gas production (Dash and Chaudhari 2005; Wang and Qu 2006; Ding et al. 2015). However, these were not intensively investigated so far. The optimized approach to improve the promotion of the electro-reduction and enable the full scale application is the use of the catalyst-modified electrodes. This strategy has been investigated for the removal of different reducible compounds from water (Chaplin et al. 2012). Wang and Qu (2006) compared different electrodes (Cu, Ti, and Pd-modified Ti electrodes), and found that the Pd-modified Cu electrode showed the highest electrocatalytic capacity and stability in the nitrate-reduction process (Wang and Qu 2006). Also, deposition of small amounts of other metals on zero valent iron have shown an increase in nitrates removal and selectivity towards nitrogen gas formation over ammonia production (Epron et al. 2001; Epron et al. 2011).

In addition, ammonia removal can be induced during electrochemical treatment via oxidation with hydroxyl radicals that generate at “non-active” type anodes (such as boron doped diamond anodes), or via reaction with hypochlorite formed at the anode in the presence of high concentration of chlorides (He et al. 2015). The latter is more applicable for wastewater treatment or possibly for the treatment of groundwater in coastal areas that are susceptible to saltwater intrusion.

The optimization of electrochemical setup for nitrates removal has been studied for both undivided (Li et al. 2010; Reyter et al. 2010; Govindan et al. 2015) and divided electrochemical cells (Dash and Chaudhari 2005; Wang and Qu 2006). Although the divided cells provide easier control of the conditions since electrolytes are split with the membrane, their use is impractical for the groundwater treatment applications. In addition, it is also noticed that in divided cells, the production of ammonia in catholyte increases over time (Ding et al. 2015). The undivided cell has advantages like simpler facility design and lower energy consumption but the water electrolysis products can adversely influence the removal of the target contaminant; oxygen formed at the anode can also be reduced at the cathode, which competes with the reduction mechanisms. A flow-through cell with the cathode placed in front of the anode with respect to the flow direction has been developed by our laboratory to minimize the adverse effect of oxygen on reduction processes at the cathode (Rajic et al. 2015a). This approach has been developed to use as in situ groundwater technology to remove trichloroethylene (TCE) from groundwater, and we found that nitrates presence adversely influences TCE removal. We found that nitrate presence adversely affects TCE hydrodechlorination by using a cathode followed by an anode sequence (Rajic et al. 2016).

The main goal of this study was to evaluate nitrates reduction by different cathodes. We tested different commercially-available and cost-effective cathode foam materials (Fe, Cu, Ni and carbon) and the presence of Pd and Ag catalysts as cathode coatings under different current intensities and flow modes to evaluate the electrochemical treatment for nitrate removal. The use of a palladized Fe foam cathode was not investigated for the nitrates removal. Additionally, we hypothesized that a cathode followed by an anode sequence would support nitrates reduction at the cathode and provide an oxidative zone at the anode for removal of ammonia.

2. Materials and Methods

All chemicals used in this study were analytical grade. Calcium sulfate was purchased from JT Baker. Sodium nitrate and sodium bicarbonate were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ·cm) from a Millipore Milli-Q system was used in all the experiments.

Ti/mixed metal oxide (MMO) mesh (3N International) was used as the anode in all experiments. The Ti/MMO electrode consists of IrO2 and Ta2O5 coating on a titanium mesh with dimensions of 36 mm diameter by 1.8 mm thickness. Fe foam (45 pores per inch, PPI, 98% iron and 2% nickel) was purchased from Aibixi Ltd., China, and Ni foam (100 PPI, Purity>99.99%) was purchased from MTI corporation. Cu foam (40 PPI, Purity>99.99%) and carbon (C) foam (45 PPI, Purity>99.99%) were purchased from Duocel®. The materials were chosen due to the commercial availability and cost. Holes (0.5 cm diameter) were drilled in the foam cathodes to prevent accumulation of gas bubbles in the cathode vicinity. Ni foam was immersed in 80 g L−1 sulfuric acid for 5 minutes to remove the oxide layer and then washed thoroughly with water. Fe electrodes were immersed in 1M HCl to remove any foreign metals and surface oxide layers. The palladization procedures for Fe and Cu foam were performed under the conditions given in Rajic et al., 2016. The Pd content at Fe and Cu was 0.5 mg cm−2 of geometric electrode surface area. The amount of Pd selected was based on our previous work and application for TCE removal (Rajic et al. 2015a). The electroplating of Ag on Fe foam was performed at −0.4 V vs SCE for 30 minutes resulting in the 68.9 mg of Ag deposited at the electrode (3.4 mg cm−2 of geometric electrode surface area).

Synthetic groundwater was prepared by dissolving 413 mg L−1 sodium bicarbonate and 172 mg L−1 calcium sulfate in deionized water. The concentrations of bicarbonate ions and calcium ions are representative of groundwater from limestone aquifers, resulting in electrical conductivity of 800 to 920 μS cm−1. The sodium nitrate was added to the solution to achieve concentrations of 50 and 100 mg L−1 of nitrates (11.25 and 22.5 mg L−1 as NO3–N). The initial pH of the contaminated synthetic groundwater was 8.2±0.3 and the initial oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) value was 210±5 mV. The temperature was kept constant at 25°C. There were no changes in the solution temperature during the treatment. Synthetic groundwater flow through the column was maintained by a peristaltic pump (Cole Parmer, Masterflex C/L). Galvanostatic conditions during treatments were maintained by an Agilent E3612A DC power supply. The experiments were conducted at current intensities which support the hydrogen formation and, therefore, the reduction of nitrates. Although hydrogen formation competes with nitrates reduction, these conditions were applied as suitable for real application and possible reduction of other species that can occur in groundwater (e.g., trichloroethylene).

Analysis of nitrates and nitrites was performed by an ion chromatography (IC) instrument (Dionex 5000) equipped with an AS20 analytical column. A KOH solution (35 mM) was used as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. Ammonia concentration in the samples was measured according to the phenate method.

A vertical acrylic column was used as an electrochemical undivided cell (Rajic et al. 2015b). The galvanostatic experiments were conducted under the experimental conditions given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions

| Foam Cathode | Catalyst Coating | Current Intensity (mA) | Flow (mL min−1) | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | - | 60, 90, 120, 200 | 3 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Fe | - | 120 | 10 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Fe | - | 120 | 3 | 11.25 and 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Ni | - | 120 | 3 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| C | - | 120 | 3 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Cu | - | 120 | 3 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Cu | Pd (0.5 mg cm−2) | 120 | 3 | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Fe | Pd (0.5 mg cm−2) | 120 | 3, 10 (circulation) | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

| Fe | Ag (3.4 mg cm−2) | 120 | 3 (circulation) | 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N |

The nitrate concentration is determined at specified times during treatment. The efficiency of the materials performance was first assessed only based on nitrates removal; the most efficient setup was further investigated on mechanisms of removal. Results are expressed as the means of the duplicate experiments, with their corresponding standard deviations being less than 5%. The control experiment (flow without the current) showed that there is no adsorption of nitrates on the reactor material, electrodes or tubing used in the experiments. Current efficiencies (CE) were calculated according to Faraday’s law; it is assumed that the electrochemical reduction of nitrate involves 5 electrons for production of nitrogen gas. Energy consumption (EC) was calculated as watt hour per g of nitrate removed after treatment (Wh g−1).

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, we tested the performance of different cathode materials for nitrates removal in an undivided electrochemical cell (Fig 1). We used Fe, Cu, C and Ni foam as commercially available electrode materials with high reactive surface areas. Using electrodes with a high active area is of great importance for flow-through systems in order to increase the time for the reaction between target contaminant and the electrode surface. The nitrates removal efficiencies for Fe and Cu foam under current intensity of 120 mA and flow of 3 mL min−1 after 3 h are 25.0% and 22.1%, respectfully. The removal efficiency for Ni foam was 6.57% and for C foam was 5.29%; results show that these materials are not suitable for the nitrates removal. Carbon foam cathode used in this study showed limited performance towards nitrate removal (5.29%) which is in accordance with other studies using graphite as cathode in an undivided cell that showed negligible nitrates removal efficiency (Dash and Chaudhari 2005). The limited performance of Ni foam under the conditions used in this study is in accordance with data from the study by Reyter et al. 2010.

Fig 1.

Nitrate removal by different cathode materials (120 mA current intensity, flow of 3 mL min−1, 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N)

We used electrode potentials that ensure water electrolysis at the anode and the cathode. By applying a DC source to the electrochemical cell, evolution of H2 and O2 was observed, suggesting water electrolysis. This approach was applied because the removal of other commonly found contaminants in groundwater utilizes the water electrolysis products for the degradation. For example, we optimized the electrochemical reactors for removal of trichloroethylene via hydrodechlorination at the cathode (Rajic et al. 2015a). Therefore, understanding the behavior of other reducible chemical species such as nitrates under those conditions is beneficial for the real application of the technology.

The electro-reduction of nitrate at the cathode is a very complex process which starts with nitrate ion adsorption at the cathode (Eq. 1.) and involves the simultaneous transfer of one electron and proton from a proton donor (e.g. water molecule, hydroxonium ion) that leads to a series of reactions where a number of products are possible: nitrite (Eg. 3), nitrogen monoxide (Eq. 4), nitrogen (Eq. 5), ammonia (Eq. 6) and hydroxyl amine (Eq. 7).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

This indicates that the energy of chemisorption of the water electrolysis intermediate (atomic hydrogen, H) at the electrode metal (Eq. 2) is of great importance for the nitrate hydrogenation. As given in the volcano plot (Zheng et al. 2015), the materials that are suitable for H evolution are lying near apices: the metal-H bond energies for those metals (noble metals) enable fast H discharge as well as H desorption from the metal surface (Conway and Jerkiewicz 2000). The materials such as Pt and Pd enable fast formation of H which further allows fast reaction with protons or other reducible species like nitrates while at the Fe electrodes, H forms slowly and reacts slowly with reducible species (Brewster 1954). Therefore, the nitrate reduction mechanism is supported by H formation; the similar removal of nitrates hydrogenation at Fe and Cu can be explained by the similar values for the metal-H bond energies.

However, the nitrates reduction is compromised by a hydrogen gas evolution reaction that takes place in parallel. In addition, in the systems that operate under very negative potentials, the reduction of nitrates at the cathode is suppressed by repulsion between the anion and similarly charged electrode. These limitations cause the overall nitrate removal efficiency for the cathode materials tested in this study (Fig 1). Also, the short retention time for the reaction in the flow through system and oxidation of reduction byproducts to nitrate adversely affect the reduction mechanism (Ding et al. 2015). However, the repulsion between nitrate and the cathode under high negative potentials might be suppressed by the presence of Na+ and Ca+ ions which may form ion pairs and ion bridges with the reacting ion (Katsounaros and Kyriacou 2008). This might influence the hydrogen evolution reaction mechanism, but the hydrogen evolution reaction through cation discharge has been investigated for Sn and Pb cathodes and was not the purpose of this study.

Cu foam

As Fig 1 shows, Cu and Fe foam show high removal efficiency compared to other materials used as cathodes. In this study, monometallic Cu foam electrode showed low overall removal efficiency, but with Pd catalyst coating of 0.5 mgPd cm−2 geometric area the removal increased by 25%, which is in accordance with previous studies. The electrochemical reduction of nitrates was mostly investigated for Cu and Pd modified Cu cathodes (de Vooys et al. 2000; Wang and Qu 2006; Reyter et al. 2010; Ding et al. 2015). It was found that Cu possesses a high ability to sorb nitrates (Eq. 1) while Pd enables fast formation of H and catalyzes the nitrites reduction (Prüsse and Vorlop 2001).

However, the overall low performance of Cu foam under tested conditions is due to the small amount of Pd used; it was previously reported that the Pd:Me as weight ratio should be equal to 4:1 or 6:1 depending of the preparation procedure for Pd–Cu catalysts (Prüsse et al. 2000). This ratio suggests a high amount of Pd, which due to its cost would be a disadvantage for the real system application. Due to low overall removal of the tested bimetallic cathode, no further investigation was performed on the nitrate removal mechanism.

Fe foam

With the use of Fe foam cathode, 25.0% of nitrates were removed when the initial nitrate concentration was 11.25 mg L−1 NO3-N (just above MCL). The final concentration after treatment was below MCL (10 mg L−1 NO3-N). The same removal efficiency is achieved with the initial concentration of 22.5 mg L−1 N-NO3 (Fig 1). As results indicate, the Fe foam showed high efficiency for nitrate removal among tested materials (Fig 1) which is in accordance with previous studies (Dash and Chaudhari 2005). However, much higher removal efficiency was accomplished in Dash and Chaundhari 2005. This is due to the generation of low redox potential in bulk solution due to iron anode use. The metallic Fe (Fe0) was found to be a suitable material to sorb nitrates and promote reduction, and it was intensively investigated for reduction on nitrates (Liou et al. 2009; Epron et al. 2011). The proposed mechanisms of Fe0 include direct electron transfer between Fe0 and nitrate and/or indirect reaction between nitrate and hydrogen formed via Fe0 corrosion. However, the sorption to the Fe0 as catalyst is limited due to corrosion.

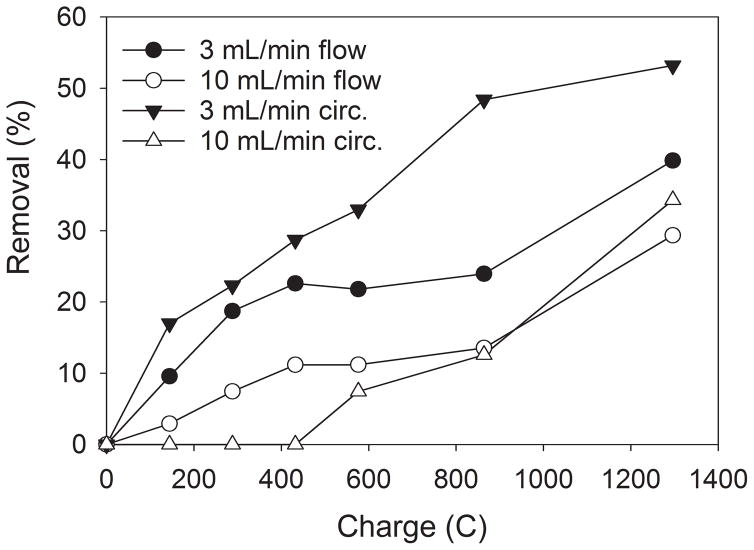

Further, we tested the presence of Pd and Ag as a catalyst coating at the Fe foam to improve the performance of the cathode (Fig 2). As mentioned, bimetallic electrodes and catalysts showed superior performance for the nitrate reduction compared to monometallic forms (Prüsse et al. 2000; Prüsse and Vorlop 2001; Li et al. 2010). The bimetallic, Pd or Ag-modified Fe cathode were not investigated for nitrates removal so far. In our system, Fe coated with Pd catalyst increased the nitrates removal to 39.8% while Ag catalyst did not show improved performance toward nitrate removal (11%). Further, we circulated the solution under 3 mL min−1 and 10 mL min−1 flow velocities in order to improve the removal efficiency of palladized Fe foam by increasing the reaction time (Fig 3). We tested different flow velocities to evaluate the influence of the mass flux. The circulation under 3 mL min−1 increased the removal from 39.8% under flow-through conditions to 53.2%. The circulation of the solution allows an increase in time for the reaction at the cathode but since the initial concentration decreases, the removal rate decreases during the course of treatment. An increase in the circulation flow rate from 3 mL min−1 to 10 mL min−1 significantly decreased the removal: from 53.2% to 34.3%, respectively. The increase in flow increases the mass flux but decreases the time needed for the reactions.

Fig 2.

Nitrate removal in the presence of different catalysts and support materials (120 mA current intensity, flow-through under 3mL min−1, 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N)

Fig 3.

Nitrate removal under flow modes and flow values (Fe/Pd foam cathode, 120 mA current intensity, 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N)

The removal mechanism in the electrochemical cell used in the study was tested by measuring the amount of nitrates, nitrites and ammonia at different sampling ports (initial, after cathode and after anode) for the palladized Fe cathode under 3 mL min−1 circulation; Fig 4 shows the nitrate removal at each sampling port. The results show that the nitrate reduction occurs after the cathode and there are no changes of removal after the anode as nitrates are not subject to oxidation. A slight increase in nitrate concentration after anode during the first 60 minutes of treatment indicates that some of the reduction byproducts oxidize to the original nitrate, similarly noticed in (Li et al. 2010). Nitrites were not detected in the samples at each sampling port. The ammonia produced after the cathode had a yield of 92±4%. However, at the steady state after the anode, the amount of ammonia decreased significantly to 50%. This implies that the cathode followed by an anode sequence can be optimized for high removal efficiency with decreased formation rate for ammonia. Ammonia oxidizes to nitrogen gas by the oxygen produced at the anode; the Ti/MMO electrode used in this study is an “active” anode which has low oxygen overpotentials and produces oxygen due to water electrolysis (Panizza and Cerisola 2009). Since there is no increase in nitrate concentration after the anode, the ammonia most likely oxidizes to nitrogen gas. After the cathode, pH value increases due to water electrolysis (Eq. 2) and nitrate reduction to nitrite (Eq. 3). The pH changes in the effluent during the treatment are negligible; the pH value of the effluent after 180 minutes of treatment is 7.5. Since H+ ions form at the anode as the result of water electrolysis the neutralization of hydroxyl ions takes place. The ability to automatically regulate pH during the treatment without any additional equipment is of great importance for the field application.

Fig 4.

Nitrate removal at different sampling ports (Fe foam cathode, 120 mA current intensity, flow of 3mL min−1, 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N)

In addition, we tested the nitrates removal with a Fe foam cathode under different current intensities (Fig 5). The increase in the current intensity from 60 mA to 120 mA resulted in a removal increase from 7.6% to 25.0%, respectively. However, under 200 mA the removal efficiency is 23%: the intensive hydrogen gas production at the cathode due to water electrolysis competes with nitrate hydrogenation and bubbles formation minimizes the sorption of nitrate ions on the cathode. The CEs for 60 mA, 90 mA, 120 mA and 200 mA are: 4.33%, 1.77%, 6.19% and 2.78%, respectively. ECs per g of nitrates removed are: 1.25 kWh g−1, 3.05 kWh g−1, 0.87 kWh g−1 and 1.94 kWh g−1. Both CE and EC indicate that 120 mA is the optimum current intensity under tested conditions.

Fig 5.

Nitrate removal under different current intensities (Fe foam cathode, flow of 3 mL min−1, 22.5 mg L−1 NO3–N, 180 min)

4. Conclusions

In this study we evaluated the removal of nitrates in the electrochemical flow-through reactor that utilized the cathode followed by an anode electrode sequence. The performance of various cathode materials was tested under different current intensities, flow rates/regimes and the presence of catalysts. Among tested materials, monometallic Fe foam cathode showed the highest nitrates removal rate. In the presence of Pd catalyst coating, Fe foam showed significant increase in nitrates removal compared to the monometallic Fe foam cathode: from 25.0% to 39.8% of nitrates removed, respectively. The increase in current intensity showed an increase in the nitrate removal rate. However, values above 120 mA caused a decrease in removal due to excessive gas formation at the cathode. The increase in flow rate from 3 mL min−1 to 10 mL min−1 decreased nitrate removal rate by 36% while the circulation under 3 mL min−1 increased the removal from 39.8% under flow-through conditions to 53.2%. The results proved that the ammonia production can be controlled by the cathode followed by an anode sequence but further optimization related to the anode material is needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, Grant No. P42ES017198). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS or the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank our laboratory technicians Michael MacNeil and Kurt Braun for building the electrochemical reactors and helping with improving the reactors’ design.

References

- Brewster J. Mechanisms of Reductions at Metal Surfaces. A General Working Hypothesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;77:6361–6363. doi: 10.1021/ja01653a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin BP, Reinhard M, Schneider WF, et al. Critical review of Pd-based catalytic treatment of priority contaminants in water. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:3655–3670. doi: 10.1021/es204087q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway BE, Jerkiewicz G. Relation of energies and coverages of underpotential and overpotential deposited H at Pt and other metals to the ‘volcano curve’ for cathodic H2 evolution kinetics. Electrochim Acta. 2000;45:4075–4083. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(00)00523-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dash BP, Chaudhari S. Electrochemical denitrificaton of simulated ground water. Water Res. 2005;39:4065–4072. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vooys aC, van Santen R, van Veen Ja. Electrocatalytic reduction of NO3− on palladium/copper electrodes. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2000;154:203–215. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(99)00375-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Della Rocca C, Belgiorno V, Meriç S. Overview of in-situ applicable nitrate removal processes. Desalination. 2007;204:46–62. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2006.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Li W, Zhao QL, et al. Electroreduction of nitrate in water: Role of cathode and cell configuration. Chem Eng J. 2015;271:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epron F, Gauthard F, Pinéda C, et al. Mechanism of nitrate reduction by zero-valent iron: Equilibrium and kinetics studies. J Hazard Mater. 2011;183:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.12.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epron F, Gauthard F, Pinéda C, Barbier J. Catalytic Reduction of Nitrate and Nitrite on Pt–Cu/Al2O3 Catalysts in Aqueous Solution: Role of the Interaction between Copper and Platinum in the Reaction. J Catal. 2001;198:309–318. doi: 10.1006/jcat.2000.3138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthard F, Epron F, Barbier J. Palladium and platinum-based catalysts in the catalytic reduction of nitrate in water: Effect of copper, silver, or gold addition. J Catal. 2003;220:182–191. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9517(03)00252-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George M, Wiklund L, Aastrup M, et al. Incidence and geographical distribution of sudden infant death syndrome in relation to content of nitrate in drinking water and groundwater levels. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:1083–1094. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan K, Noel M, Mohan R. Removal of nitrate ion from water by electrochemical approaches. J Water Process Eng. 2015;6:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2015.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield JL, Burkart MR, Stoner JD, et al. Nitrogen in Groundwater Associated with. 2008;Chapter 7:177–202. [Google Scholar]

- He S, Huang Q, Zhang Y, et al. Investigation on Direct and Indirect Electrochemical Oxidation of Ammonia over Ru–Ir/TiO 2 Anode. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015;54:1447–1451. doi: 10.1021/ie503832t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hörold S, Tacke T, Vorlop K-D. Catalytical Removal of Nitrate and Nitrite from Drinking-Water.1. Screening for Hydrogenation Catalysts and Influence of Reaction Conditions on Activity and Selectivity. Environ Technol. 1993;14:931–939. [Google Scholar]

- Katsounaros I, Kyriacou G. Influence of nitrate concentration on its electrochemical reduction on tin cathode: Identification of reaction intermediates. Electrochim Acta. 2008;53:5477–5484. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Feng C, Zhang Z, et al. Treatment of nitrate contaminated water using an electrochemical method. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:6553–6557. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou YH, Lin CJ, Weng SC, et al. Selective decomposition of aqueous nitrate into nitrogen using iron deposited bimetals. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:2482–2488. doi: 10.1021/es802498k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizza M, Cerisola G. Direct And Mediated Anodic Oxidation of Organic Pollutants. Chem Rev. 2009;109:6541–6569. doi: 10.1021/cr9001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintar a. Catalytic hydrogenation of aqueous nitrate solutions in fixed-bed reactors. Catal Today. 1999;53:35–50. doi: 10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00101-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pintar a, Setinc M, Levec J. Hardness and Salt Effects on Catalytic Hydrogenation of Aqueous Nitrate Solutions. J Catal. 1998;174:72–87. doi: 10.1006/jcat.1997.1960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prüsse U, Hähnlein M, Daum J, Vorlop K-D. Improving the catalytic nitrate reduction. Catal Today. 2000;55:79–90. doi: 10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00228-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prüsse U, Vorlop KD. Supported bimetallic palladium catalysts for water-phase nitrate reduction. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2001;173:313–328. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(01)00156-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajic L, Fallahpour N, Alshawabkeh AN. Impact of electrode sequence on electrochemical removal of trichloroethylene from aqueous solution. Appl Catal B Environ. 2015a;174–175:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajic L, Fallahpour N, Alshawabkeh AN. Impact of electrode sequence on electrochemical removal of trichloroethylene from aqueous solution. Appl Catal B Environ. 2015b;174–175:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajic L, Fallahpour N, Podlaha E, Alshawabkeh A. The influence of cathode material on electrochemical degradation of trichloroethylene in aqueous solution. Chemosphere. 2016;147:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond Becker Z, Mills K. [Accessed 13 March 2016];Technology Review of BAT for Removal of Nitrate in Drinking Water. 2013 http://cefns.nau.edu/capstone/projects/CENE/2014/NitrateTreatabilityOptimization/Project%20Documents/Technology%20Review.pdf.

- Reyter D, Belanger D, Roue L. Nitrate removal by a paired electrolysis on copper and Ti/IrO2 coupled electrodes - Influence of the anode/cathode surface area ratio. Water Res. 2010;44:1918–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Qu J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate in water with a palladium-modified copper electrode. Water Environ Res. 2006;78:724–729. doi: 10.2175/106143006X110665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Jiao Y, Jaroniec M, Qiao SZ. Advancing the electrochemistry of the hydrogen-Evolution reaction through combining experiment. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2015;54:52–65. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]