Abstract

Background

Young adults (18 to 39 years old) with hypertension have the lowest rates of blood pressure control (defined as blood pressure less than 140/90 mmHg) compared to other adult age groups. Approximately 1 in 15 young adults have high blood pressure, increasing their risk of future heart attack, stroke, congestive heart failure, and/or chronic kidney disease. Many young adults reported having few resources to address their needs for health education on managing cardiovascular risk.

Objective

The goal of our study was to develop and disseminate a website with evidence-based, clinical information and health behavior resources tailored to young adults with hypertension.

Methods

In collaboration with young adults, health systems, and community stakeholders, the My Hypertension Education and Reaching Target (MyHEART) website was created. A toolkit was also developed for clinicians and healthcare systems to disseminate the website within their organizations. The dissemination plan was guided by the Dissemination Planning Tool of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Results

Google Analytics data were acquired for January 1, 2017 to June 29, 2017. The MyHEART website received 1090 visits with 2130 page views; 18.99% (207/1090) were returning visitors. The majority (55.96%, 610/1090) approached the website through organic searches, 34.95% (381/1090) accessed the MyHEART website directly, and 5.96% (65/1090) approached through referrals from other sites. There was a spike in site visits around times of increased efforts to disseminate the website.

Conclusions

The successfully implemented MyHEART website and toolkit reflect collaborative input from community and healthcare stakeholders to provide evidence-based, portable hypertension education to a hard-to-reach population. The MyHEART website and toolkit can support healthcare providers’ education and counseling with young adults and organizations’ hypertension population health goals.

Keywords: hypertension, young adults, World Wide Web, quality improvement, patient engagement

Introduction

Prevalence of Hypertension among Young Adults

Uncontrolled hypertension among young adults (18 to 39 year-olds) [1] is an enormous public health burden [2,3]. In the United States, over 10 million 18 to 39 year-olds (1 in 5 men; 1 in 6 women) have hypertension [4-7], increasing their risk of premature heart failure, stroke, and chronic kidney disease [4,8-11]. Young adults with hypertension have a high lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease due to the longer exposure to high blood pressures and ongoing risk of organ damage [11-17]. Hypertension control reduces morbidity, mortality, and future healthcare costs [18-22]. Yet, only 40% of young adults with hypertension in the United States have achieved blood pressure control (defined as a blood pressure less than 140/90 mmHg) [23-27]. Our prior research demonstrated that within 1 year of developing hypertension, almost half of young adults do not receive guideline recommended lifestyle counseling [28]. Young adults are also less likely to receive a hypertension diagnosis and, if necessary, medication initiation compared to middle-aged and older adults [29,30].

Hypertension Control Barriers among Young Adults

To further understand barriers to young adults achieving hypertension control, we engaged racially and ethnically diverse young adults in 6 focus groups and conducted one-on-one interviews with primary care providers [31,32]. Two focus groups were conducted at each site: 1 academic, 1 urban, and 1 rural healthcare system [31,32]. The young adult respondents identified hypertension education topics that were not commonly addressed in current educational materials [32]. Young adult respondents shared their preferred social media channels and requested Web-based education to provide flexible access to hypertension information “when they wanted it” [32]. Primary care providers shared similar views of lacking hypertension materials and/or the time for extended education for young adults [31]. Both groups also highlighted other common barriers (eg, transportation, work-life balance, financial limitations) to hypertension care delivery. The combined qualitative and quantitative data highlighted the need to provide a website tailored to young adults with hypertension.

Prior studies demonstrated that when patients with hypertension receive health education targeted to their needs, their self-management of hypertension improves (eg, behavior changes, home blood pressure monitoring) [33]. In addition, patient education should provide a sense of personal medical empowerment to promote, initiate, and maintain health behavior changes [32,34]. Finally, hypertension education can serve as a bridge between clinic visits. To address an unmet need in the delivery of hypertension care for young adults, we developed the My Hypertension Education and Reaching Target (MyHEART) program, a young adult hypertension education program.

Rationale for Development of the MyHEART Website

The aims of MyHEART are to (1) decrease barriers to young adult hypertension care delivery; and (2) improve hypertension control in this hard to reach population. It is known that website education alone is insufficient for long-term health behavior change; however, it can be effective as an additional component to ongoing hypertension control initiatives [35]. Therefore, the goals of the MyHEART website [36] are to (1) be a portable resource for young adults’ questions and challenges with managing blood pressure; and (2) supplement the hypertension clinical care and education of healthcare teams and organizations. The aims of this proposal were to (1) develop the architectural structure of the MyHEART website through community engagement partnerships; and (2) launch and disseminate the MyHEART website to clinicians, healthcare systems, and community organizations committed to hypertension control.

Methods

Ethics

Prior studies [31,32,37] that informed the MyHEART website development were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) and informed consent was obtained from patient and clinician stakeholders. Neither IRB approval nor written consent were needed to design or implement this website because the data that informed MyHEART development was already described in the original IRB submission for the prior studies.

MyHEART Website Development

Community Stakeholders

Our stakeholders consisted of 38 young adult patients with a mean age of 26.7 (SD 9.6) years old and were 34% (13/38) male, 45% (17/38) Black, and 42% (16/38) with 1 or more years of college [32]. In addition, there were 15 primary care clinicians [31] and 3 hypertension quality improvement teams across multiple healthcare systems. The Wisconsin Network for Research Support (WINRS) is a community and patient engagement resource based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing. WINRS developed the Community Advisors on Research Design and Strategies (CARDS), an innovative consultation service that engages lay community members. CARDS includes members from diverse backgrounds, including underrepresented communities and “hard to reach” populations. Members are trained to (1) review project materials (eg, websites, survey questions, mobile phone apps); and (2) provide unique feedback for research, education, and outreach. For our website development, 10 to 12 CARDS members were engaged monthly for 6 months, either in-person or by electronic communication, for feedback on content, architecture, and dissemination plans [38]. In addition, there were 2 90-minute meetings with the CARDS group to discuss updated MyHEART versions and pilot test the user-interface, website usability, and technological options for accessing Web information (eg, mobile phone, tablet).

Website Architecture

We built the website in partnership with the University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program (HIP) using the Drupal 7 Content Management Framework (TurnKey Linux). Based on stakeholder input, the MyHEART website has the following 3 main categories (Multimedia Appendix 1): (1) defining blood pressure and understanding high blood pressure; (2) information on initiating and maintaining behaviors to control blood pressure; and (3) relevant resources, such as exercise options, questions for clinicians, and recipes via website links to the American Heart Association (AHA), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and National Institutes of Health (NIH). We also feature peer-reviewed publications on cardiovascular health in young adults from established scientific resources (eg, NIH, CDC, AHA) because young adult focus group informants requested to be kept up-to-date [32]. A Twitter feed (@MyHeartMyChoice) was included as another means of sharing important health topics with young adults. A discussion forum is being designed and will be added in the future as the MyHEART program staff expands to support the exchange of ideas.

Iterative Website Design Process

The website’s architectural structure was cyclically evaluated by the lay advisory group (CARDS), information technology specialists, and clinical content experts (ie, physicians, nurses) using established categories: internal reliability, external security, content usefulness, navigation usability, and system interface attractiveness [39,40]. A sample of the detailed notes on MyHEART’s architectural structure is in shown in Multimedia Appendix 2; CARDS lay advisory group full meeting notes are available upon written request to the corresponding author. The educational content for the website was formatted with a Flesch-Kincaid readability of the 6th grade or less [41]. Website edits continued over 12 months, with testing on desktop and mobile computer devices, until the final iteration was launched in January 2017.

Website Toolkit

A toolkit was developed for the MyHEART website to assist clinicians and healthcare systems with incorporating the website in clinical practice and community outreach. The toolkit provides customizable materials and Web and social media communication drafts to share the website with members of their organization (Multimedia Appendix 3).

Website Dissemination

The Dissemination Planning Tool of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [42] was used to outline and navigate the dissemination plan that was started in February 2017. The website and toolkit were first disseminated through HIPxChange [43] in association with the University of Wisconsin HIP. In late 2012, HIP launched HIPxChange to disseminate evidence-based programs, tools, and other materials for free to the public [44]. The goal of HIPxChange is to accelerate the translation of new and existing knowledge into clinical practice to improve healthcare delivery and health outcomes.

Additional dissemination avenues included clinician notifications, academic and healthcare marketing teams, university/campus health centers, research communities, and public community announcement boards (eg, grocery stores, coffee shops, etc). Regional dissemination efforts include the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ). This is a voluntary consortium of 37 Wisconsin healthcare organizations (physician groups, hospitals, health plans) that has led the nation in measuring and improving healthcare quality for multiple chronic conditions [45,46]. Social media streams (eg, Facebook, Twitter, health blogs) have been activated.

Results

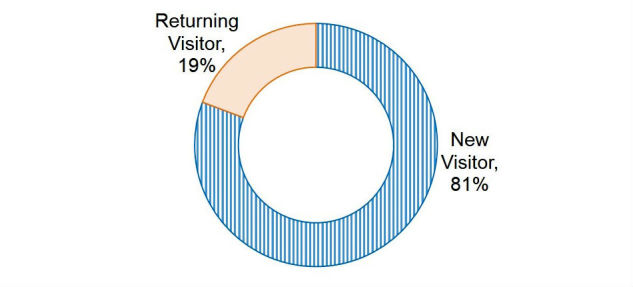

Google Analytics data were acquired for January 1, 2017 to June 29, 2017. In this time, the MyHEART website received a total of 1090 visits, with an average of 1.95 pages/session (range 1 to 7 pages/session for 95% of users). The number of site visits were in line with our expectations during this implementation period. Among the site visitors, 81.01% (883/1090) were new visitors (Figure 1). The majority (55.96%, 610/1090) approached the website through organic searches, 34.95% (381/1090) accessed the MyHEART website directly, and 5.96% (65/1090) approached through referrals from other sites. Overall, 40 sessions (3.67%, 40/1090) were referred from social media; 23 (2.11%, 23/1090) from Twitter, and 17 (1.56%, 17/1090) from Facebook, with Facebook demonstrating a greater number of unique visitors (10) than Twitter (2 unique visitors).

Figure 1.

Percentage of new versus returning visitors to the MyHEART website from January 1, 2017 to June 29, 2017 (N=1090).

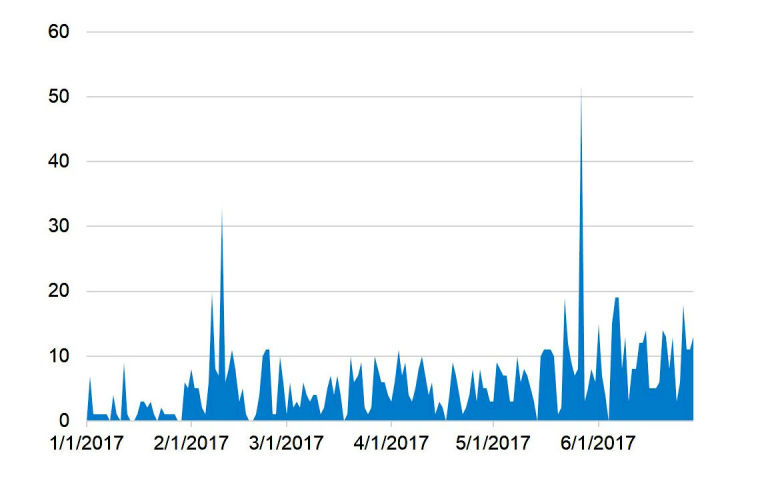

Among new users, the bounce rate was 77%, while the bounce rate among returning users was 49%. Most users spent a short time on the site (0 to 10 seconds), but the time among the remaining users was approximately evenly distributed between 11 and 1800 seconds. The page with the largest number of views among new users was “What do the blood pressure numbers mean?” (eg, understanding blood pressure values). Interestingly, among new users who accessed that page, the majority (89.8%, 495/551 of page views) accessed the page by conducting an organic search; new users spent an average of 2 minutes and 32 seconds on this page. Across all viewers, the most viewed content was the “What do the blood pressure numbers mean?” (55.41%, 604/1090 views), followed by the MyHEART website home page (47.06%, 513/1090 views). The spike in website visits noted during February and May 2017 (Figure 2) likely reflects stages of the MyHEART website dissemination plan and viewers directly accessing the MyHEART website via academic center emails, newsletters, and media inquiries.

Figure 2.

Number of visitors per day to the MyHEART website from January 1, 2017 to June 29, 2017.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The MyHEART website and corresponding toolkit were successfully developed with diverse young adult, community, and academic stakeholders. The website can provide young adults with evidence-based hypertension information to support their self-management goals. The corresponding toolkit can support clinicians’ efforts to share knowledge about hypertension with young adults and offer counseling about behavior change. The authors successfully engaged clinical staff and their patients across healthcare systems and are actively working to engage young adults in the community (with limited healthcare access). The MyHEART website’s accessibility on mobile platforms helps target the young adult population. However, the authors are learning how to increase the duration of engagement of young adults on the website. For example, an interactive functionality is in development with the goal of increasing the length of time young adults use the website and acquire hypertension information.

Limitations

We recognize that the website and toolkit were created in English, limiting access to young adults and clinicians who are not fluent in English. However, our team plans to make these materials available in Spanish. The website also currently lacks interactivity, but we plan to add this in the near future. Finally, we did not conduct a comparative analysis with other technology or programs. We are continuing to expand our dissemination activities and will develop multidimensional interventions in the future.

Conclusions

In collaboration with young adults, health systems, and community stakeholders, the MyHEART young adult website is a portable resource to provide evidence-based information to a hard-to-reach population. The MyHEART website and toolkit provide resources for patients, clinicians, and healthcare organizations to improve hypertension control in young adults

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) [grant number 1UL1RR025011], and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) [grant number UL1TR000427]. Heather M. Johnson is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH [grant number K23HL112907]. Additional support was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from The Wisconsin Partnership Program.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. None of the sponsors had a role in study design, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- AHA

American Heart Association

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- CARDS

Community Advisors on Research Design and Strategies

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control

- HIP

Health Innovation Program

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MyHEART

My Hypertension Education and Reaching Target

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- WCHQ

Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality

- WINRS

Wisconsin Network for Research Support

Selected screenshots of the MyHEART website.

Sample of detailed notes from CARDS Lay Advisory Group meeting on MyHEART's architectural structure.

Examples of promotional materials for healthcare providers in the MyHEART toolkit.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: HJ and JL conceptualized and designed the study. HJ, JL, CB, RW, LZ, RH, KS, and DL were responsible for the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be submitted. The authors greatly appreciate the time and continued dedication of the CARDS lay advisory group who provided the foundation for the MyHEART website. We are also grateful for the staff and students at the University of Wisconsin HIP who provided assistance with proofreading the website.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013 Oct;(133):1–8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db133.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, Sanchez E. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Apr 01;63(12):1230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0735-1097(13)06077-4 .S0735-1097(13)06077-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2020: Heart Disease and Stroke. Washington, DC: 2014. [2017-04-30]. Increase the proportion of adults with hypertension whose blood pressure is under control https://www.healthypeople.gov/node/4555/data_details . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Group Members. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de FS, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee. Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Jan 26;133(4):e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=26673558 .CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988-2008. JAMA. 2010 May 26;303(20):2043–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650.303/20/2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen QC, Tabor JW, Entzel PP, Lau Y, Suchindran C, Hussey JM, Halpern CT, Harris KM, Whitsel EA. Discordance in national estimates of hypertension among young adults. Epidemiology. 2011 Jul;22(4):532–41. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821c79d2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21610501 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . High Blood Pressure Facts. Atlanta, GA: 2016. [2017-09-10]. http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999 Sep;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5.S0738-3991(98)00116-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grubbs V, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, Peralta CA, Bansal N, Jacobs DR, Siscovick DS, Lewis CE, Bibbins-Domingo K. Body mass index and early kidney function decline in young adults: a longitudinal analysis of the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Apr;63(4):590–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.055. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24295611 .S0272-6386(13)01442-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schold JD, Goldfarb DA, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, Mandelbrot DA, Heaphy ELG, Fatica RA, Poggio ED. Comorbidity burden and perioperative complications for living kidney donors in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Oct;8(10):1773–82. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12311212. http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=24071651 .CJN.12311212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell AB, Cole JW, McArdle PF, Cheng Y, Ryan KA, Sparks MJ, Mitchell BD, Kittner SJ. Obesity increases risk of ischemic stroke in young adults. Stroke. 2015 Jun;46(6):1690–2. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008940. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=25944320 .STROKEAHA.115.008940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones DW, Peterson ED. Improving hypertension control rates: technology, people, or systems? JAMA. 2008 Jun 25;299(24):2896–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2896.299/24/2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1.S0140-6736(05)17741-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bautista LE. High blood pressure. In: Remington PL, Brownson RC, Wegner MV, editors. Chronic disease epidemiology and control. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2010. pp. 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D'Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Levy D. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006 Feb 14;113(6):791–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548206. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16461820 .CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brosius FC, Hostetter TH, Kelepouris E, Mitsnefes MM, Moe SM, Moore MA, Pennathur S, Smith GL, Wilson PWF, American Heart Association KidneyCardiovascular Disease Council. Councils on High Blood Pressure Research‚ Cardiovascular Disease in the Young‚EpidemiologyPrevention. Quality of CareOutcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. National Kidney Foundation Detection of chronic kidney disease in patients with or at increased risk of cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease Council; the Councils on High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group: Developed in Collaboration With the National Kidney Foundation. Hypertension. 2006 Oct;48(4):751–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177321. http://hyper.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16990648 .48/4/751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernan WN, Dearborn JL. Obesity increases stroke risk in young adults: opportunity for prevention. Stroke. 2015 Jun;46(6):1435–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009347. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=25944321 .STROKEAHA.115.009347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van HL, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD, American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task ForceStatistics Committee Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010 Feb 02;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20089546 .CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paramore LC, Halpern MT, Lapuerta P, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Fairchild DG, Bates D. Impact of poorly controlled hypertension on healthcare resource utilization and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2001 Apr;7(4):389–98. http://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=612 .612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ, National Heart‚ Lung‚Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention‚ Detection‚ Evaluation‚Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun 07;356(23):2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935.356/23/2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yano Y, Stamler J, Garside DB, Daviglus ML, Franklin SS, Carnethon MR, Liu K, Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones DM. Isolated systolic hypertension in young and middle-aged adults and 31-year risk for cardiovascular mortality: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Feb 03;65(4):327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.060. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0735-1097(14)07093-4 .S0735-1097(14)07093-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014 Feb 05;311(5):507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427.1791497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, Flack JM, Carter BL, Materson BJ, Ram CVS, Cohen DL, Cadet J, Jean-Charles RR, Taler S, Kountz D, Townsend RR, Chalmers J, Ramirez AJ, Bakris GL, Wang J, Schutte AE, Bisognano JD, Touyz RM, Sica D, Harrap SB. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014 Jan;16(1):14–26. doi: 10.1111/jch.12237. doi: 10.1111/jch.12237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland N, Segraves D, Nnadi VO, Belletti DA, Wogen J, Arcona S. Identifying barriers to hypertension care: implications for quality improvement initiatives. Dis Manag. 2008 Apr;11(2):71–7. doi: 10.1089/dis.2008.1120007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma J, Urizar GG, Alehegn T, Stafford RS. Diet and physical activity counseling during ambulatory care visits in the United States. Prev Med. 2004 Oct;39(4):815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.006.S0091743504001641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Statistics CommitteeStroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Mar 07;135(10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28122885 .CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson HM, Olson AG, LaMantia JN, Kind AJH, Pandhi N, Mendonça EA, Craven M, Smith MA. Documented lifestyle education among young adults with incident hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 May;30(5):556–64. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3059-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25373831 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, Schumacher JR, Palta M, Pandhi N, Sheehy AM, Smith MA. Undiagnosed hypertension among young adults with regular primary care use. J Hypertens. 2014 Jan;32(1):65–74. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000008. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24126711 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, Schumacher JR, Palta M, Pandhi N, Sheehy AM, Smith MA. Antihypertensive medication initiation among young adults with regular primary care use. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 May;29(5):723–31. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2790-4. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24493322 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson HM, Warner RC, Bartels CM, LaMantia JN. “They're younger… it's harder.” Primary providers' perspectives on hypertension management in young adults: a multicenter qualitative study. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Jan 03;10(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2332-8. https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13104-016-2332-8 .10.1186/s13104-016-2332-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson HM, Warner RC, LaMantia JN, Bowers BJ. “I have to live like I'm old.” Young adults' perspectives on managing hypertension: a multi-center qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016 Mar 11;17:31. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0428-9. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-016-0428-9 .10.1186/s12875-016-0428-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saksena A. Computer-based education for patients with hypertension: a systematic review. Health Educ J. 2010 May 04;69(3):236–245. doi: 10.1177/0017896910364889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauver DR, Ward SE, Heidrich SM, Keller ML, Bowers BJ, Brennan PF, Kirchhoff KT, Wells TJ. Patient-centered interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2002 Aug;25(4):246–55. doi: 10.1002/nur.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004 Nov 10;6(4):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. http://www.jmir.org/2004/4/e40/ v6e40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MyHEART. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program; 2017. http://myheartmychoice.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson HM, LaMantia JN, Warner RC, Pandhi N, Bartels CM, Smith MA, Lauver DR. MyHEART: a non randomized feasibility study of a young adult hypertension intervention. J Hypertens Manag. 2016;2(2) doi: 10.23937/2474-3690/1510016. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28191544 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephan G, Hoyt MJ, Storm DS, Shirima S, Matiko C, Matechi E. Development and promotion of a national website to improve dissemination of information related to the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) in Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2015 Oct 22;15:1077. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2422-x. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-015-2422-x .10.1186/s12889-015-2422-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong S, Kim J. Architectural criteria for website evaluation – conceptual framework and empirical validation. Behav Inf Technol. 2004 Sep;23(5):337–357. doi: 10.1080/01449290410001712753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiou W, Lin C, Perng C. A strategic framework for website evaluation based on a review of the literature from 1995–2006. Inform Manage. 2010 Aug;47(5-6):282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2010.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Naval Technical Training Command Research Branch Report 8-75. Millington, TN: Naval Air Station Memphis; 1975. Feb, [2017-09-13]. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a006655.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter D, Nieva V, Albaghal T, Sorra J. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: 2005. [2017-09-13]. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation volumes 1-4 http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/advances-in-patient-safety/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson H, LaMantia J. HIPxChange. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program; 2016. MyHEART: information & resources for young adults with hypertension https://www.hipxchange.org/MyHEART . [Google Scholar]

- 44.HIPxChange. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program; 2016. https://www.hipxchange.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berwick DM. Improving patient care. My right knee. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jan 18;142(2):121–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00011.142/2/121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . Quality Field Notes: Public Reporting. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015. May, [2017-09-13]. What we're learning: how to report on the quality of physician practices http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2015/rwjf419545 . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Selected screenshots of the MyHEART website.

Sample of detailed notes from CARDS Lay Advisory Group meeting on MyHEART's architectural structure.

Examples of promotional materials for healthcare providers in the MyHEART toolkit.