Abstract

Objectives

To examine colorectal cancer screening practices among colonoscopy specialists from 5 countries and inform public health needs in improvement of the ongoing global crisis in colorectal cancer.

Methods

An online survey among colonoscopy specialists was conducted in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States. The survey covered topics on colonoscopy practices in the screening as well as in the treatment setting, as well as expected trends.

Results

Participating colonoscopy specialists included 114 physicians from the United States, 81 from France, 80 from Germany, 80 from the United Kingdom, and 156 from Japan. Survey results revealed that 59%–73% of colonoscopies were performed in patients aged 50–75 years old, with 15%–23% performed in patients <50 years old. The proportion of patients with age-based versus symptom-based first colorectal cancer screening varied by country and age. Sedation protocols varied by country; however, rate of incomplete colonoscopy was low in all countries. The proportion of negative first colonoscopies decreased with age in all countries.

Conclusions

This multi-country survey of real-world clinical practices suggests a need for improved participation in population age-based colorectal cancer screening and possibly younger age of screening initiation than currently recommended by guidelines. The variation among countries in the proportion of patients who received their first colonoscopy due to age-based colorectal cancer screening versus symptom-based initial colonoscopy indicates that population-based screening initiatives and improved health outcomes will benefit from public health awareness programs.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Screening, Colorectal cancer, European Union, Japan, United States

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major burden throughout the world, with over 1.4 million cases, 95% of which are adenocarcinomas [1], and 693,900 deaths occurring worldwide in 2012 [2]. It can largely be prevented by the detection and removal of adenomatous polyps [3], and survival is significantly better when colorectal cancer is diagnosed while localized [4]. For that reason, population-based screening is widely recommended in both Europe and the US, and guidelines have been prepared to provide recommendations on colorectal cancer screening approaches.

Over the last decade, a whole range of technologies have been introduced in clinical practice to diagnosed and treat colorectal cancer [5], [6], [7], [8]. In term of screening, various non-invasive techniques, such as fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) and stool DNA tests (FIT-DNA) have been developed, as well as blood based tests [5], [6], [7], [8]. The main advantage of these tests is their convenience for the patients which could improve colorectal cancer screening uptake. Although these tests are more comfortable for patients, recent clinical trial results showed there is still room for improvement in terms of test sensitivity [9], [10]. Therefore, colonoscopy remains an important technique for the screening of colorectal cancer [11].

Recent advances in the field of colonoscopy, including new technologies [12] and techniques that improve polyp detection and mucosal resection and improvements in colorectal pathology management have led to improved patient care [13], [14]. As colonoscopy remains the standard of care for colorectal cancer screening and management in Western countries, we wanted to determine how this translates into the daily routine of colonoscopists. In this paper, we describe the practices of colonoscopists in 5 countries, namely France, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK), the US and Japan. Our goal was to examine practices related to the colonoscopy procedure, including the purpose of the first colonoscopy procedure, rate of incomplete procedures, sedation protocols, and practices following positive colonoscopies, as well as age of the patients receiving first colonoscopies. Additionally, we examined trends in the volume of procedures performed during the previous 2 years.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample

Endoscopists from France, Germany, the UK, the US, and Japan were invited to take an online survey to determine current practices in colorectal cancer screening in their countries. In the US, 340 endoscopists were invited by email from the Deerfield Institute (New York, NY, USA) proprietary panel of colorectal surgeons, gastroenterologists and internal medicine specialists. In France, Germany, the UK, and Japan, an external provider, M3 Global Research, was used to contact endoscopists. M3 is a panel provider which has access to a broad range of physicians, including those who specialize in gastroenterology or colorectal surgery. A total of 1154 gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons were contacted in France, 1002 in Germany, 1428 in the UK, and 10,182 in Japan. Because the M3 panel did not document participants' experience in colonoscopy specifically, all gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons were invited. Eligibility to complete the survey was determined through the screening criteria related to colonoscopy specialty practice. Colonoscopy specialists were eligible to participate if they personally performed at least 10 colonoscopies in a typical month and if their practice contained at least 2 endoscopy rooms. Based on these criteria, it is believed that only specialists with experience in colonoscopy entered the survey. All respondents were invited by email to participate in the survey, which was accessible online from March 3, 2016 to April 3, 2016. Participants were offered an industry-standard honorarium as compensation for their time in completing the survey.

By electing to complete the survey, respondents provided consent to use their anonymous responses to the survey questions. The study did not involve patients and data on patient characteristics within colonoscopy practices were provided only in the aggregate. As such, there was no institutional review board and/or licensing committee involved in approving the research and no need for informed consent from the participants per US regulations (§46.116 General requirements for informed consent. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.102).

2.2. Survey design

The survey was developed to assess current colon screening practices by colonoscopy specialists. The online questionnaire consisted largely of quantitative questions that addressed topics related to colonoscopy practices and patient characteristics. Colonoscopy practice information reported by survey respondents included general practice information (ie, number of colonoscopies performed in the past 12 months, sedation protocol, complications, patient volume trend in the previous 2 years), characteristics of first colonoscopies (ie, reasons for performing, proportion of complete versus incomplete colonoscopies, reasons for incomplete colonoscopies, outcomes of colonoscopies performed, procedures performed during positive colorectal cancer screening), and reasons for follow-up colonoscopies performed. Patient characteristics reported by survey respondents included proportion of male and female patients and proportion of patients in age groups <50 years old, 50–64 years old, 65–75 years old, and >75 years old. Survey participants also answered qualitative questions assessing the trend in patient volume for colonoscopy procedures in the past 2 years.

2.3. Data analysis

The individual identities of the survey respondents were blinded to the study authors. All survey data obtained from each country were analyzed separately. Results were categorized by country (France, Germany, the UK, the US, and Japan) and by patient age groups (<50 years old, 50–64 years old, 65–75 years old, >75 years old). The planned analyses for quantitative data were descriptive statistics and included means and percentages. Data from each respondent was weighted by the total number of colonoscopies they performed to account for the differences between large and small practices. No formal statistical tests were performed as no specific hypothesis was intended to be tested. Qualitative data were assessed thematically and coded according to the main themes of the survey questions. Any responses that addressed multiple themes were counted as multiple comments.

3. Results

In the US, 138 of the 340 recipients of the Deerfield Institute survey responded; 114 met eligibility criteria for number of procedures/procedure rooms and completed the survey. From the M3 panel, a total of 954 physicians responded to the survey invitation, and 397 met eligibility criteria and completed the survey, including 81 from France, 80 from Germany, 80 from the UK, and 156 from Japan.

3.1. Colonoscopy patient characteristics

The distribution of colonoscopy procedures among age groups (Table 1) shows that across all 5 countries, 59%–73% of colonoscopies were performed in patients aged between 50 and 75 years old. This is in line with the EU and US guidelines for initiating colorectal cancer screening colonoscopy in patients aged 50–75 years. Patients outside of this age bracket do receive colonoscopy as well, with 15%–23% of patients below 50 years old and 14%–21% of patients older than 75 years of age receiving colonoscopy across the 5 countries (Table 1). The patient ratios by sex were similar across countries, with reported male patient screening of 48% in the US, 50% in Germany and the UK, 52% in France, and 55% in Japan.

Table 1.

Split of colonoscopies performed by country and patient age group.

| Country | Number of colonoscopies during 12-month period (Mean) | Proportion of colonoscopy per patients' age group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 y | 50 to 64 y | 65 to 75 y | >75 y | ||

| France | 685.6 | 21% | 35% | 28% | 16% |

| Germany | 702.8 | 23% | 36% | 27% | 14% |

| UK | 343.5 | 23% | 28% | 31% | 18% |

| US | 1303.8 | 15% | 45% | 28% | 12% |

| Japan | 436.8 | 20% | 27% | 33% | 21% |

UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Based on 81 colonoscopists in France, 80 in Germany, 80 in the UK, 114 in the US and 156 in Japan.

3.2. Colonoscopy general practice

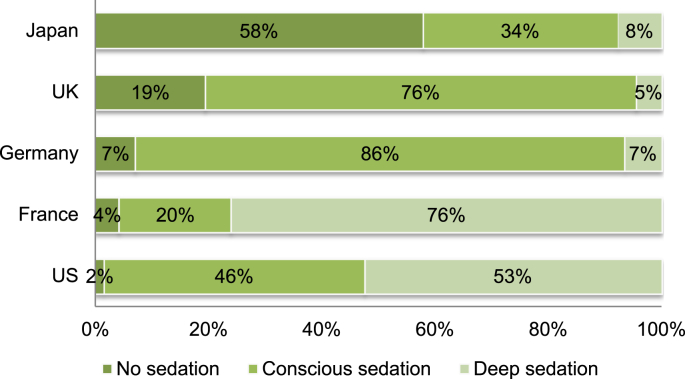

Sedation protocols varied greatly by country (Fig. 1). Absence of sedation was most common in Japan at 58% of patients. Conscious sedation was most common in Germany (86% of patients) and the UK (76% of patients), and deep sedation was most common in the US (53% of patients) and France (76% of patients).

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopy sedation protocols used by each country. The proportions of patients receiving no sedation, conscious sedation, and deep sedation are reported within each country. UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

The proportion of patients who experienced complications during or directly following colonoscopy was reported as 2% in France, 1% in Germany, the UK, and Japan, and <1% in the US. When complications did occur, it was primarily bleeding (ranging from 45% in France to 60% in Germany), followed by perforation in France and Japan (22% and 15%, respectively), and cardiorespiratory events in Germany, the UK, and the US (12%, 13%, and 16%, respectively). Peritonitis-like syndrome ranked third in all countries (ranging from 9% in the US to 21% in France).

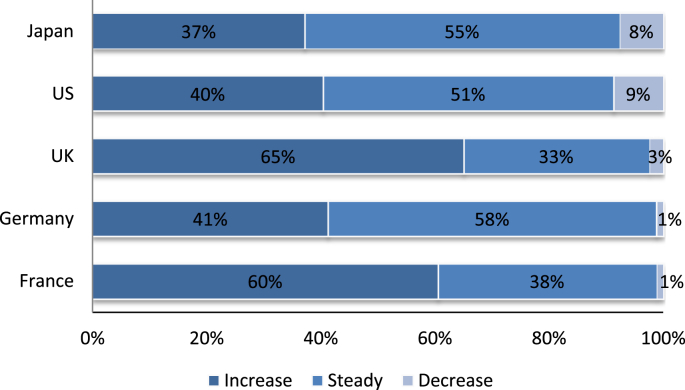

Survey respondents who reported an increase in colonoscopy patient volume in the past two years ranged from 37% of respondents in Japan to 65% in the UK (Fig. 2). Colonoscopy specialists in France, Germany, Japan and the UK most frequently reported an increased demand as the reason for the increase in colonoscopy patient volume. In the US, survey respondents reported the increase in patient case volume was driven by more screening and referrals. Increased awareness was the third most common reason for more screening in all countries. Among the survey respondents in which decreases in colonoscopy patient volumes were reported, ranging from 1% of respondents in France and Germany, 3% in the UK, 8% in Japan and 9% in the US, explanations for those decreases were not clear.

Fig. 2.

Trends in colonoscopy patient volume over the previous 2 years. The proportion of colonoscopists reporting an increase, steady rate, or decrease in patient volume over the previous 2 years is shown within each country. UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

3.3. Initial colonoscopy

Table 2 shows the reasons for performing a first colonoscopy among patient age groups by country. In France, Germany, and the US, the main reasons for performing the first colonoscopy varied by age group. Among patients <50 years old and from 50 to 64 years old, abdominal complaints initiated the first colonoscopy. The second most common reason for first colonoscopy in these age groups in these same countries was colorectal cancer screening. And, among patients 65–75 years old, colorectal cancer screening was the main reason for first colonoscopy. For patients >75 years old, abdominal pain and colorectal cancer screening were primary reasons for the procedure. In the UK, a first colonoscopy was most often performed because of complaints of abdominal pain, regardless of age. In Japan, across all age groups, the key reason for first colonoscopy screening was to confirm and/or treat patients with a positive noninvasive colorectal cancer test.

Table 2.

Colonoscopist reported reasons for first colonoscopy by patient age group and country, in proportion of patients.

| Patient age group | Reason for first colonoscopy | France | Germany | UK | US | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 y | Colorectal cancer screening | 30% | 24% | 9% | 20% | 24% |

| Confirmation and/or treatment for patients with a positive noninvasive testa | 15% | 16% | 11% | 18% | 54% | |

| Patient with ischemic bowel disease | 4% | 3% | 5% | 3% | 5% | |

| Patient with abdominal complaintsb | 46% | 54% | 71% | 56% | 15% | |

| Other | 5% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 2% | |

| 50 to 64 y | Colorectal cancer screening | 30% | 24% | 9% | 20% | 24% |

| Confirmation and/or treatment for patients with a positive noninvasive testa | 15% | 16% | 11% | 18% | 54% | |

| Patient with ischemic bowel disease | 4% | 3% | 5% | 3% | 5% | |

| Patient with abdominal complaintsb | 46% | 54% | 71% | 56% | 15% | |

| Other | 5% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 2% | |

| 65 to 75 y | Colorectal cancer screening | 33% | 45% | 29% | 53% | 25% |

| Confirmation and/or treatment for patients with a positive noninvasive testa | 25% | 20% | 17% | 17% | 46% | |

| Patient with ischemic bowel disease | 9% | 8% | 7% | 6% | 8% | |

| Patient with abdominal complaintsb | 31% | 25% | 44% | 24% | 19% | |

| Other | 3% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 2% | |

| >75 y | Colorectal cancer screening | 30% | 34% | 18% | 30% | 25% |

| Confirmation and/or treatment for patients with a positive noninvasive testa | 18% | 21% | 13% | 23% | 39% | |

| Patient with ischemic bowel disease | 12% | 10% | 8% | 10% | 10% | |

| Patient with abdominal complaintsb | 36% | 31% | 58% | 35% | 23% | |

| Other | 4% | 4% | 3% | 1% | 2% |

UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Based on 81 colonoscopists in France, 80 in Germany, 80 in the UK, 114 in the US and 156 in Japan.

Positive noninvasive test includes guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT), immunochemical FOBT (iFOBT), or stool DNA (sDNA).

Abdominal complaints include abdominal pain, constipation, weight loss, diarrhea, gastrointestinal tract bleeding and other abdominal symptoms.

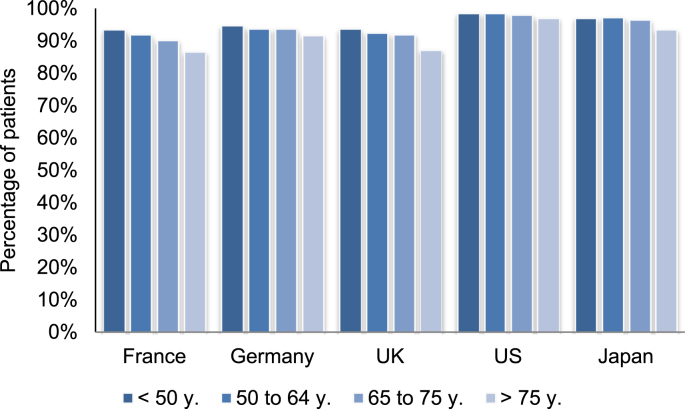

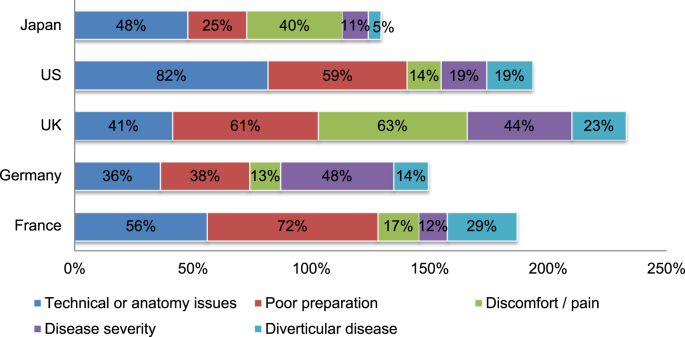

Among patients who had their first colonoscopy performed for colorectal cancer screening, the majority had a complete colonoscopy (Fig. 3). In all countries surveyed, the rate of complete colonoscopy slightly decreased with age. France had the lowest rate of complete colonoscopy, ranging from 87% among patients >75 years to 94% among patients <50 years old. The US had the highest rate of complete colonoscopy, ranging from 97% to 99% over all age groups. The reasons for incomplete colonoscopy varied by country (Fig. 4). Poor preparation was the main cause in France (72% of incomplete procedures) followed by technical or anatomy issues (56%). Disease severity (48%), poor preparation (38%), and technical or anatomy issues (36%) were most common in Germany. Discomfort or pain (63%) and poor preparation (61%) were the most common reasons for incomplete procedures in the UK. In the US and Japan, technical or anatomy issues were the main reason (82% and 48%, respectively), followed by poor preparation in the US (59%) and discomfort or pain in Japan (40%).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients who received complete colonoscopies. The proportion of patients with complete colonoscopies is reported for patients who underwent their first colonoscopy for the purpose of colorectal cancer screening. Percentages are reported by patient age group within each country. UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Fig. 4.

Reasons reported for incomplete colonoscopies. The reasons underlying incomplete colonoscopy procedures among patients who received their first colonoscopy for the purpose of colorectal cancer screening are shown by country, in proportion of mentions. More than one reason could be reported for an individual patient. UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

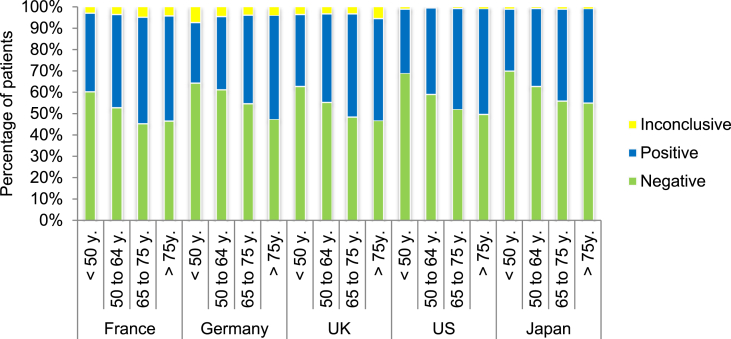

Fig. 5 shows the outcomes of first colonoscopies by country and patient age groups. The overall proportion of negative colonoscopies varied from 51% in France to 61% in Japan. When looking across age groups, the proportion of negative colonoscopies decreased with age in all countries. For patients <50 years old, negative colonoscopy ranged from 60% in France to 70% in Japan. For patients >75 years old, negative colonoscopy ranged from 45% in Japan to 53% in France, Germany, and the UK. The rate of inconclusive colonoscopy was 1% in the US and Japan, and ranged from 3% to 7% in other countries surveyed.

Fig. 5.

Colonoscopy outcomes in patients receiving their first colonoscopy. Positive, negative, and inconclusive outcomes are shown for patients receiving their first colonoscopy for the purpose of colorectal cancer screening. Outcomes are reported by patient age group within each country, in proportion of patients. UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Among patients with a positive colonoscopy during colorectal cancer screening, the most common procedure performed for all patients in all countries was removal of pathological lesions (Table 3). Some country differences were identified, with Japan and the UK having the lowest rate of removal of pathological lesions, and the US the highest. For patients without lesion removal, colonoscopy specialists most commonly performed a biopsy. Nothing was done in a few instances, either because the patients needed to be referred to another center or they were scheduled to return for removal of pathological lesions.

Table 3.

Colonoscopist reported procedures with positive colonoscopy by patient age group and country, in proportion of patients.

| Patient age group | Action taken with positive colonoscopy | France | Germany | UK | US | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 y | Removal of pathological lesions | 70% | 72% | 69% | 92% | 61% |

| Biopsy without removal of pathological lesions | 19% | 13% | 20% | 6% | 26% | |

| Nothing, the patient will be referred to another center for treatment | 7% | 5% | 3% | 1% | 4% | |

| Nothing, there was not enough time to remove lesions, patient will come back for removal of pathological lesions | 3% | 5% | 6% | 1% | 9% | |

| Other | 1% | 5% | 1% | 0% | 1% | |

| 50 to 64 y | Removal of pathological lesions | 73% | 77% | 67% | 91% | 61% |

| Biopsy without removal of pathological lesions | 18% | 12% | 18% | 7% | 23% | |

| Nothing, the patient will be referred to another center for treatment | 5% | 3% | 4% | 1% | 4% | |

| Nothing, there was not enough time to remove lesions, patient will come back for removal of pathological lesions | 3% | 3% | 5% | 1% | 11% | |

| Other | 2% | 6% | 5% | 0% | 1% | |

| 65 to 75 y | Removal of pathological lesions | 71% | 81% | 67% | 88% | 57% |

| Biopsy without removal of pathological lesions | 18% | 12% | 18% | 8% | 23% | |

| Nothing, the patient will be referred to another center for treatment | 5% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 8% | |

| Nothing, there was not enough time to remove lesions, patient will come back for removal of pathological lesions | 5% | 4% | 4% | 1% | 11% | |

| Other | 1% | 2% | 7% | 0% | 1% | |

| >75 years | Removal of pathological lesions | 70% | 82% | 61% | 82% | 60% |

| Biopsy without removal of pathological lesions | 16% | 11% | 25% | 12% | 20% | |

| Nothing, the patient will be referred to another center for treatment | 6% | 3% | 7% | 2% | 9% | |

| Nothing, there was not enough time to remove lesions, patient will come back for removal of pathological lesions | 6% | 3% | 6% | 3% | 11% | |

| Other | 2% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Based on 81 colonoscopists in France, 80 in Germany, 80 in the UK, 114 in the US and 156 in Japan.

3.4. Follow-up colonoscopy

Table 4 provides the reasons given for follow-up colonoscopies by country and patient age group. For patients who had 2 or more colonoscopies, the survey respondents reported that surveillance was the main reason for the additional procedures, ranging from 59% in the UK to 81% in the US. The rate of a second colonoscopy due to a first inconclusive or incomplete colonoscopy ranged from 7% in the US to 18% in France and Germany. The rate that a second colonoscopy was performed because the patient was not treated during the first colonoscopy ranged from 3% in the US to 20% in Japan. Further breakdown of reasons for follow-up colonoscopy by patient age groups is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Colonoscopist reported reasons for follow-up colonoscopy by patient age group and country, in proportion of patients.

| Age | Reason for follow-up colonoscopy | France | Germany | UK | US | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 y | First colonoscopy was inconclusive or incomplete, and had to be redone | 19% | 17% | 11% | 7% | 13% |

| First colonoscopy was positive but patient was not treated at that time | 14% | 14% | 16% | 3% | 19% | |

| Surveillance colonoscopy following pathological lesions removal | 62% | 60% | 60% | 75% | 60% | |

| Other | 5% | 9% | 13% | 15% | 8% | |

| 50 to 64 y | First colonoscopy was inconclusive or incomplete, and had to be redone | 19% | 16% | 15% | 7% | 14% |

| First colonoscopy was positive but patient was not treated at that time | 17% | 13% | 17% | 2% | 20% | |

| Surveillance colonoscopy following pathological lesions removal | 61% | 60% | 59% | 83% | 61% | |

| Other | 4% | 10% | 9% | 8% | 6% | |

| 65 to 75 y | First colonoscopy was inconclusive or incomplete, and had to be redone | 19% | 20% | 14% | 7% | 10% |

| First colonoscopy was positive but patient was not treated at that time | 11% | 14% | 17% | 2% | 22% | |

| Surveillance colonoscopy following pathological lesions removal | 65% | 59% | 60% | 83% | 64% | |

| Other | 4% | 7% | 9% | 8% | 5% | |

| >75 y | First colonoscopy was inconclusive or incomplete, and had to be redone | 16% | 19% | 16% | 7% | 13% |

| First colonoscopy was positive but patient was not treated at that time | 14% | 12% | 16% | 3% | 19% | |

| Surveillance colonoscopy following pathological lesions removal | 67% | 64% | 56% | 83% | 63% | |

| Other | 4% | 5% | 12% | 7% | 5% |

UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; y, years.

Based on 81 colonoscopists in France, 80 in Germany, 80 in the UK, 114 in the US and 156 in Japan.

4. Discussion

Recent technological and technical advances in colonoscopy procedures have improved patient care in several aspects, including increasing the likelihood of avoiding surgery through enhanced surveillance [13]. Colonoscopy plays a fundamental role in prevention of colorectal cancer and remains the standard for both diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring among practicing gastroenterologists [13]. Given the availability of colonoscopy screening, with demonstrated effectiveness in the prevention of colorectal cancer and improved survival [11], [15], [16], it remains unknown why colorectal cancer continues to be a global health crisis with high rates of patient mortality [2], [17], [18], [19]. Clearly, a more detailed understanding of the real-world clinical practices of colonoscopy specialists and characteristics of the use of colonoscopy with their patients is needed.

To address this need, the purpose of our study was to investigate colonoscopy practice in several Western countries and Japan from the point of view of the colonoscopist. Consistent with key identified benefits of colonoscopy [4], our results show the most common procedure conducted during a positive colonoscopy was lesion removal, followed by biopsy, among all countries. And, the main reason given by colonoscopists for follow-up colonoscopies was surveillance. Our survey revealed that although the patient's first colonoscopy is largely performed in patients within the recommended age range of 50–75 years old, some country differences exist. The US had the lowest rate of colonoscopy outside the recommended 50–75 years old age range compared to France, Germany, the UK, and Japan. This may change in the US as some authors are advocating the necessity to screen patients at a younger age [20], [21].

When assessing the reasons that drove patients to seek colonoscopy, we also identified some country differences in the proportion of patients undergoing age-based screening versus symptom-based first colonoscopy. In Japan, the first driver of colonoscopy was confirmation of a positive noninvasive test. In the UK, first colonoscopy was mainly performed because of patients' abdominal complaints. Colorectal cancer screening was rarely mentioned as the reason to perform colonoscopy in the UK. In France, Germany and the US, although patients' abdominal complaints was the number one reason, it was less prevalent than in the UK, and colorectal cancer screening was more often the colonoscopy driver than in the UK. Interestingly, in France, Germany and the US colorectal cancer screening was the main driver for patients aged 65–75 years old. These findings depict some differences in national approaches to colorectal cancer prevention and detection. Public health programs aimed at increasing participation in screening may improve health outcomes through decreased incidence of colorectal cancer and improved survival [11], [15].

Our results identified some geographical differences in sedation practices, although they appear to have little impact on the procedure outcome for the majority of patients. Although sedation in colonoscopy is important for patient comfort, our data appear to indicate that sedation level does not directly impact colonoscopy completion in the majority of patients. Note that France, which has the highest proportion of deep sedation (76% of patients), also has the lowest proportion of complete colonoscopies; the main reason given for this is poor patient preparation. In contrast, Japan, which has the highest level of no sedation (58% of patients), has the second highest proportion of complete colonoscopies. The primary reasons for incomplete colonoscopies given by colonoscopists in Japan were technical or anatomy issues followed by discomfort or pain. In the UK, with a high proportion of patients receiving conscious sedation, discomfort or pain and poor preparation were most common with incomplete procedures. Thus, among a minority of patients, lower levels of sedation and higher discomfort or pain may be associated with incomplete procedures.

Strengths of this study include the multi-country perspectives from practicing colonoscopist specialists and the focus on real-world clinical practice. A limitation is the small subset of colonoscopy specialists within each country who participated in our survey, and caution should be used when generalizing results to the entire population of colonoscopists. Additionally, as with any survey, our findings may be influenced by the recall and response bias of the surveyed individuals. Because a broad base of potentially eligible respondents were recruited by the Deerfield Institute (for the US) and the M3 panel (for all other countries), and these survey recipients self-selected to complete the survey based on their eligibility as a colonoscopy specialist, a global response rate could not be calculated. Importantly, all respondents answered the same survey questions. There were no differences in the questionnaires, outside of translation, whether respondents were recruited by the Deerfield Institute or the M3 panel.

5. Conclusion

This is the first multi-country survey focusing on current practices of colonoscopy specialists. Importantly, colonoscopy failure rates were low across countries. Sedation protocols varied by country but these differences appeared to have little impact on colonoscopy success rate for the majority of patients. A key finding from this survey is that countries varied in the proportion of patients who received their first colonoscopy due to age-based colorectal cancer screening versus symptom-based initial colonoscopy. This finding indicates that population based screening initiatives and improved health outcomes will benefit from public health awareness programs that further optimize patient participation in age-based colorectal cancer screening. The most common patient age ranges at which colonoscopies were performed for colorectal cancer screening were largely consistent with the recommendations of US and EU guidelines. However, a notable proportion of patients younger than 50 years old received colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening. This finding, along with recent suggestions to start screening patients earlier, indicates that the number of colonoscopies performed is likely to increase in the future.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund International. Colorectal cancer statistics. Available at: http://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/data-specific-cancers/colorectal-cancer-statistics.

- 2.Torre L.A., Bray F., Siegel R.L., Ferlay J., Lortet-Tieulent J., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;2015(65):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corley D.A., Jensen C.D., Marks A.R. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1298–1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin B., Lieberman D.A., McFarland B. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008;2008(58):130–160. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sameer A.S., Nissar S. Epigenetics in diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2016;5:49–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comas M., Mendivil J., Andreu M., Hernandez C., Castells X. Long-term prediction of the demand of colonoscopies generated by a population-based colorectal cancer screening program. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baxter N.T., Koumpouras C.C., Rogers M.A., Ruffin M.T., Schloss P.D. DNA from fecal immunochemical test can replace stool for detection of colonic lesions using a microbiota-based model. Microbiome. 2016;4:59. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iovanescu D., Frandes M., Lungeanu D., Burlea A., Miutescu B.P., Miutescu E. Diagnosis reliability of combined flexible sigmoidoscopy and fecal-immunochemical test in colorectal neoplasia screening. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6819–6828. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S122425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Church T.R., Wandell M., Lofton-Day C. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63:317–325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imperiale T.F., Ransohoff D.F., Itzkowitz S.H., Levin T.R., Lavin P., Lidgard G.P., Ahlquist D.A., Berger B.M. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1287–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan J., Xin L., Ma Y.F., Hu L.H., Li Z.S. Colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with non-malignant findings: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;111:355–365. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Utsumi T., Iwatate M., Sano W. Polyp detection, characterization, and management using narrow-band imaging with/without magnification. Clin. Endosc. 2015;48:491–497. doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.48.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gromski M.A., Kahi C.J. Advanced colonoscopy techniques and technologies. Tech. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015;17:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee T.J., Nair S., Beintaris I., Rutter M.D. Recent Adv. colonoscopy. 2016;5 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7567.1. F1000 Faculty Rev-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner H., Jansen L., Ulrich A., Chang-Claude J., Hoffmeister M. Survival of patients with symptom- and screening-detected colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:44695–44704. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDevitt J., Comber H., Walsh P.M. Colorectal cancer incidence and survival by sub-site and stage of diagnosis: a population-based study at the advent of national screening. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11845-016-1513-8. published online 28 October 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; 2016. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf Available at: (Last Accessed 6 December 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferlay J., Steliarova-Foucher E., Lortet-Tieulent J. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Japan. Cancer country profiles. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/jpn_en.pdf?ua=1 (Last Accessed 6 December 2016).

- 20.Cash B.D., Banerjee S., Anderson M.A. Ethnic issues in endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:1108–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis D.M., Marcet J.E., Frattini J.C., Prather A.D., Mateka J.J., Nfonsam V.N. Is it time to lower the recommended screening age for colorectal cancer? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011;213:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]