Abstract

Purpose

In 1991, we described the recruitment and goals for a cohort of young adults. At the time, little was known about long-term retention of young, healthy and mobile adults or minorities. We present retention strategies and rates over 25 years, and predictors of participation at the year 25 follow-up examination of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study, a longitudinal investigation of coronary artery disease risk factors in a biracial population initially ages 18–30 years recruited from four U.S. centers in 1985.

Methods

CARDIA has employed a range of strategies to enhance retention, including two contacts per year, multiple tracking methods to locate participants lost-to-follow-up, use of birthday and holiday cards, participant newsletters, examination scheduling accommodations and monetary reimbursements, and a standing committee whose primary purpose has been to continually review retention rates and strategies and identify problems and successes.

Results

For 25 years, CARDIA has maintained >90% contact with participants between examinations, over 80% at any 2-year interval, and a 72% 25-year examination attendance rate. Baseline predictors of year 25 examination attendance include white race, female sex, older age, higher education, nonsmoking and moderate alcohol consumption.

Conclusion

Consistent use of multiple retention strategies, including attention to contact rates and sharing of best strategies across study centers, has resulted in high retention of a diverse, initially young, biracial cohort.

Keywords: Retention rates, Retention strategies, Longitudinal studies, Cohort studies

Abbreviations and acronyms

- CARDIA

Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults

- CC&RS

Clinic Coordination and Retention Subcommittee

- Y25

year 25

- Y20

year 20

- Y2

year 2

- U.S.

United States

- BMI

Body mass index

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

1. Introduction

In 1991, we described the recruitment and goals for a cohort of black and white young adults with variable educational attainment [1]. At the time, little was known about long-term retention of young, healthy and mobile adults or minorities. Twenty-five years later, we describe recruitment and retention strategies for this population-based biracial cohort of young adults, initially ages 18–30 years in 1985–86, recruited from four geographic locations [9,10]. Participant retention in long-term longitudinal studies is critical for both internal and external validity. A number of factors have been positively associated with study retention, including white race [[2], [3], [4]], female sex [3,4] and higher level of educational attainment [2,3,5], while smoking [2,4], obesity [4,6], and moderate-severe depression levels [5] have been associated with lower participant retention.

Two recent systematic reviews have examined retention strategies and their effects on retention [7,8]. Most of the studies reviewed were randomized trials of less than two years' duration. In general, the more retention strategies employed, the better the retention, with incentives, both monetary and nonmonetary, improving retention; reminder calls and letters were also consistently found to improve retention, but to a lesser degree. Booker et al. [8] noted that retention strategies for longitudinal studies may be different from shorter term clinical trials due to long-term commitment.

Observational studies of chronic diseases require long follow-up, but systematic evaluations of retention strategies in these studies are lacking. Participants in closed cohorts after a baseline recruitment period are irreplaceable. Studying methods currently used in existing cohorts, as well as characteristics of these populations and the accompanying retention rates, is a logical strategy to understand retention success, but has not been done for middle-aged participants.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study is a longitudinal investigation of coronary artery disease risk factors in black and white men and women that has followed participants for over 25 years. To date, CARDIA has completed eight examination cycles: a baseline examination during 1985–1986 (n = 5115) and follow-up examinations at 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years after baseline. The CARDIA Study recruitment was designed to be balanced across eight strata: race (black/white), sex (men/women), age (18–24/25-30 years) and educational attainment (high school education or less/more than high school) in four distinct geographic locations (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA).

This cohort provides a unique opportunity to describe retention strategies from young adulthood through middle age, as well as predictors of long-term retention over 25 years.

2. Methods

2.1. Overall retention strategies

Since the CARDIA Study began in 1985, the study protocol for participant retention has included the following: 1) obtaining information on three designated contacts for each participant at a mid-year and annual contact; 2) producing bimonthly standardized contact reports reviewed by the study investigators; and 3) creating a Clinic Coordination and Retention Subcommittee (CC&RS) to facilitate retention. Retention methods used were approved by the Institutional Review Board of each field center and the Coordinating Center. Information on three designated contacts was obtained from participants at the time of initial enrollment, including name, relation to participant, mailing address and telephone numbers. Follow-up contacts are made every six months to verify each participant's contact information and vital status, and to update designated contact information. In later years, this information has also included email addresses, if available. Either the participant or a proxy can provide information for this mid-year contact. At annual follow-up contacts, each participant's health and hospitalization status are also obtained. The Coordinating Center posts standardized contact reports bimonthly on a secure internal website for field center coordinators and study investigators to review; the CC&RS meets monthly to identify both problems and successful methods. Because staff and retention techniques vary by field center, the CC&RS members also exchange successful local retention strategies.

Across field centers, specific methods of contact have varied between using the U.S. Postal Service as the initial contact mode, followed by telephone contact for those not returning forms, and telephone contact for both initial and reminder contact. Although not explicitly part of the study protocol, all field centers send birthday and holiday cards to participants as another retention strategy; family members are sent condolence cards in the event of a participant death.

2.2. Year 25 examination retention activities

Retention strategies have been comparable across clinics for all examinations, with some variation in implementation. We will focus on the year 25 (Y25) examination, when the participants were ages 43–55 years.

Participant satisfaction questionnaire. To help inform investigators during planning for the Y25 examination, a brief questionnaire was added to the mid-year follow-up contact preceding the examination to solicit participant opinions (Appendix A). Early on, CARDIA investigators obtained responses to study satisfaction questions in order to give participants a voice in planning for future follow-up examinations. The satisfaction questionnaire provides a pathway for enhanced collaboration between investigators and participants.

Participant newsletters. Annual study-wide participant newsletters highlight clinical results from examinations, inform participants of upcoming examinations and the components, introduce participants to center-specific staff or news, and to share select scientific publications. Prior to the Y25 examinations, participants were also mailed a refrigerator magnet with the examination dates and all relevant field center contact information.

Toll-free number. Each field center maintains a toll-free number as a convenience for out-of-town participants to contact either their baseline examination clinic or examining clinic (if different from baseline clinic) as well as a general email address.

Travel accommodations. Each field center offers transportation assistance at no cost to participants for local clinic visits. CARDIA is distinctive for offering reimbursement for travel expenses to out-of-town participants who have relocated outside the immediate area of their home clinic. This can include airfare, hotel accommodations and/or mileage reimbursement. Participants can choose to return to their home clinic or to be examined at the field center closest to their current residence. Clinic staff often tries to coordinate a clinic visit with a planned visit to the area for other purposes, which not only assures the participant will be in the area, but also provides a positive incentive by helping him or her with the cost of travel plans.

Scheduling accommodations. Each field center offers alternate appointment options for participants with time constraints, including completing their examination over multiple days and alternate appointment times, such as later in the morning or an afternoon clinic. Abbreviated exams (see Appendix B for details), ranked by research priorities, are offered to participants with limited time and who would not otherwise attend the examination.

Reimbursement and ‘thank you’ gifts. Each field center offers study non-monetary gifts, such as t-shirts, for participation and monetary reimbursement for participant time and expenses. Monetary reimbursement of up to $60 for the core examination was also provided to each participant who attended the Y25 examination to cover parking, child care, missed work, or other expenses; the timing and form of payment varied across sites. The Birmingham clinic provided a Visa CheckCard for the full amount at the conclusion of each participant's examination visit, while the Chicago clinic provided $40 in cash at the conclusion of each participant's examination visit and subsequently mailed him/her a $20 check; the Minneapolis and Oakland clinics both provided a check for the full amount. Reimbursement for ancillary studies was independent of the core examination and provided additional incentive for participants to complete all parts of a planned examination. (See www.CARDIA.dopm.uab.edu for examination components at initial and follow-up examinations and concurrent ancillary studies.) Reimbursement has increased over time to account for current costs.

Test results. Participants are provided with select examination results on component-specific forms. For the Y25 examination, results of both blood pressure and anthropometric measurements were provided at the clinic visit, and all other results were mailed as completed, including lipids, glucose, albumin/creatinine ratio, coronary calcium from a computed tomography scan, echocardiography results, and other components performed on subsets of participants (e.g., glycated hemoglobin, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain). Not every participant completed all examination components, and results were sent when the subset of results for each participant was complete. Investigators compared results to previous exams to determine if the findings were chronic or new, and letters were tailored to participants with health information they may not get from a routine physician visit. For some, this individual attention provided an additional incentive to attend the examination and to continue participating in the CARDIA Study.

Scheduling process. Each field center had a specific process for scheduling Y25 examination visits, including telephone and text messaging, followed by an appointment confirmation letter with instructions for fasting, what type of clothing to wear, a map to the clinic, parking information and a plastic bag for participants to carry medications to the examination. A worksheet listing participant contacts was also included in that mailing to complete prior to the clinic visit that was similar to the mid-year contact form. Two days prior to the examination date, clinic staff called the participant to confirm the appointment and to verify participant understanding of directions and instructions for the clinic visit. In general, if a participant was 30 min late to the appointment, staff called to check on him/her. Participants who were frequent re-schedulers or no-shows also were given an additional reminder call the evening before the examination date, either by the site's clinic coordinator or the Principal Investigator. Some participants had a taxi scheduled to pick them up if they either did not have reliable transportation or had missed appointments in the past.

Locating participants. Each field center uses a variety of free and paid methods to locate participants lost to follow up: online search engines (TransUnion, LexisNexis, Accurint and Intelius People Search), prisoner searches (federal, state and county) and mortality searches (Social Security Death Index, National Death Index, ObitFinder and Ancestry.com). Participant contacts are used and the U.S. Post Office's return mail services provide forwarding addresses if a participant has moved since a prior successful contact.

2.3. Retention rates and predictors of 25-year retention

It is well known in the epidemiologic literature that retention rates differ by race, sex, and educational attainment. CARDIA's original recruitment design was balanced on race, sex, age, and education within each field center to establish a cohort with sufficient numbers of participants to examine how these factors contribute to cardiovascular risk factor development. Therefore, we examined retention by race-sex group, by field center, and by education both at baseline when education was still in progress and by Year 25 exam attendance. Specifically, we examined retention overall and by race-sex group for each examination year (Table 1). Then focusing on Y25 examination attendance, we examined retention by race-sex and field center (Table 2). Next, examined retention by educational attainment within race-sex group, separately for education attained at baseline and at Y25 examination (Table 3). Independent of examination attendance, we calculated contact rates for the most recent five years as a measure of our ability to locate cohort members (Table 4). Chi-square tests were performed to ascertain statistical significance of differences in proportions retained.

Table 1.

Percent of living participants who attended each examination, overall and by race-sex group; Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study.

| Examination Year | ALL |

Race-sex Groupa |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black men |

Black women |

White men |

White women |

|||||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |

| Y02 | 90.5 | (4622) | 85.5 | (988) | 87.8 | (1298) | 94.3 | (1102) | 94.6 | (1234) |

| Y05 | 85.7 | (4351) | 79.3 | (905) | 82.5 | (1214) | 90.9 | (1054) | 90.3 | (1178) |

| Y07 | 80.6 | (4085) | 73.2 | (831) | 77.6 | (1143) | 87.2 | (1006) | 84.7 | (1105) |

| Y10 | 78.5 | (3948) | 72.2 | (806) | 76.4 | (1120) | 83.0 | (950) | 82.3 | (1072) |

| Y15 | 73.6 | (3671) | 64.8 | (709) | 70.1 | (1021) | 80.2 | (911) | 79.4 | (1030) |

| Y20 | 71.9 | (3548) | 60.0 | (646) | 69.8 | (1005) | 78.7 | (889) | 78.4 | (1008) |

| Y25 | 72.1 | (3497) | 63.0 | (654) | 69.4 | (986) | 77.3 | (863) | 78.2 | (994) |

| ALLb | 48.8 | (2493) | 33.2 | (384) | 43.7 | (647) | 58.9 | (690) | 59.2 | (772) |

| At least 1c | 96.7 | (4944) | 94.8 | (1097) | 95.8 | (1418) | 98.0 | (1147) | 98.2 | (1282) |

From chi-square tests assessing proportions retained at each examination year, p < .001 for each year.

Attended all 7 post-baseline examinations.

Attended at least one post-baseline examination.

Table 2.

Y25 Retention by Race-sex groups within field center.

| Birmingham | Chicago | Minneapolis | Oakland | ALL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black males | 73.9% | 61.4% | 53.8% | 62.2% | 62.7% |

| Black females | 78.2% | 74.2% | 62.3% | 63.8% | 69.2% |

| White males | 75.4% | 77.9% | 77.2% | 79.1% | 77.4% |

| White females |

69.3% |

81.4% |

78.3% |

81.3% |

78.0% |

| 74.5% | 74.4% | 69.4% | 70.6% | 72.0% |

Table 3.

Percent of participants by education at baseline, alive at time of year 25 examination, and who attended the year 25 examination, by race-sex group; Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study.

| Entire cohort |

Alive at Y25 |

Attended Y25 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline education >HS |

Baseline education >HS |

Baseline education >HS |

Year 25 education >HS |

|||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |

| ALL |

32.2 |

(1638) |

32.7 |

(1579) |

36.6 |

(1276) |

64.8 |

(2256) |

| Black men | 17.9 | (206) | 18.2 | (188) | 19.5 | (127) | 45.0 | (292) |

| Black women | 19.5 | (288) | 19.7 | (279) | 21.6 | (212) | 56.3 | (552) |

| White men | 45.5 | (529) | 46.1 | (512) | 49.9 | (429) | 74.3 | (641) |

| White women | 47.2 | (615) | 47.3 | (600) | 51.2 | (508) | 77.9 | (771) |

>HS: More than high school education.

Table 4.

Percent of living participants with whom contact has been made, overall and by race-sex group; Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study.

| Contacted perioda | Black men |

Black women |

White men |

White women |

ALL |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |

| at or after Y25 | 89.1 | (901) | 92.8 | (1291) | 95.6 | (1039) | 95.6 | (1197) | 93.4 | (4428) |

| in last 5 years | 88.4 | (894) | 92.4 | (1285) | 95.1 | (1034) | 95.4 | (1195) | 93.0 | (4408) |

| in last 2 years | 83.1 | (840) | 88.5 | (1231) | 92.1 | (1001) | 93.8 | (1175) | 89.6 | (4247) |

As of December 15, 2015, from chi-square tests, p < .001 for each of the 3 time periods.

Baseline characteristics—field center, demographics (age, race, sex and education), health behaviors (smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and diet), indices of social support, body mass index (BMI), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol levels—were used to predict Y25 examination attendance in logistic regression models. Field center was entered in the model because recruitment and retention methods differ slightly, including continuity of field center retention staff, an unmeasured characteristic with unknown effects. The field centers also represent different underlying populations, specifically, with respect to race and education. Variables that were statistically significantly (p < .05) associated with attendance were entered simultaneously into the regression model. Variables that did not achieve statistical significance were removed in a stepwise manner until only statistically significant variables remained. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated. This process was repeated for Y20 examination attendance to assess robustness of findings in predicting long-term retention and examination attendance. All analyses were conducted using SAS v. 9.3. We finish with presenting geographically where participants were living at time of Y25 examination relative to their original field center.

3. Results

The overall examination attendance relative to baseline from Y2 to Y25 was 91%, 86%, 81%, 79%, 74%, 72% and 72% of the surviving cohort, respectively, with 49% attending all seven post-baseline examinations and 97% attending at least one post-baseline examination (Table 1).

Retention differed by race-sex at each examination (all p's < .001). When assess differences only by race, differences were significant at each examination (all p's < .001); whites had 8% higher in earlier years (Y02, Y05) increasing to 10–13% in later examinations. Differences by sex were only present (p < .01) at Y20 and Y25. Among whites, there were no differences in retention by sex across examination years (all p's > .60). In contrast, among African-American/Blacks, retention was consistently, significantly higher for women than men starting with YR05 (difference of 3%, p = .04) thru YR25 (difference of 6%, p < .001).

Findings were similar across field centers with Birmingham having greater retention of black men and less retention of White women than the other three field centers, exemplified in the Y25 examination (p < .001 for retention across centers; Table 2).

Educational attainment at baseline and at Y25 is shown in Table 3. At baseline, 32% of participants had more than a high school education, 46% in whites vs. 19% in blacks, with little difference by sex. This racial difference remained when restricted to participants alive at the time of Y25, and to those who attended the Y25 examination. As might be expected from a cohort that was recruited in age range where education is likely to continue, the percent of participants with more than a high school education almost doubled by Y25, from 36.6% to 64.8%, with racial differences comparable to baseline. There was also a sex difference, with higher proportions of women than men attending the Y25 examination having more than a high school education, especially among blacks (p < .001).

We have maintained contact with 83–94% of study participants, depending on race-sex group, within the prior two years, and we have maintained contact with 88–95% within the prior five years (Table 4). Differences in contact rates across race-sex groups were similar to attendance rates, specifically, higher for whites than blacks (all p < .001).

Table 5 shows baseline participant characteristics that were statistically significant predictors of Y25 examination attendance. After adjustment for field center, white race, older age, and more than high school education at baseline were each associated with 40–50% higher odds of attending Y25 in a multivariable model. Female sex was associated with 19% higher odds of attendance, and current smoking status at baseline was associated with 30% lower odds of attendance. Alcohol use had an inverse U-shaped association with attendance (overall p = .048): compared to nondrinkers, participants who drank between 7 and 21 mL of alcohol/day were 28–43% more likely to attend, while the light (<7 mL/day) and very heavy drinkers (>=21 mL/day) did not differ from nondrinkers. BMI, physical activity, calories, total cholesterol and social support were not associated with Y25 examination attendance. Findings were similar when analyzed for Y20 examination attendance (not shown).

Table 5.

Multivariable-adjusted odds of Y25 examination attendance; Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study.

| Baseline characteristica | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| White vs. black | 1.50 | 1.30, 1.72 | <.001 |

| Women vs. men | 1.19 | 1.04, 1.36 | .01 |

| Age (>25 vs. ≤25 years) | 1.50 | 1.28, 1.68 | <.001 |

| Education (>HS vs. ≤HS) | 1.46 | 1.21, 1.66 | <.001 |

| Currently smokes cigarettes vs. does not (past and never) | 0.67 | 0.58, 0.78 | <.001 |

| Alcohol | .048 | ||

| None | 1.00 | Referent | |

| <7 mL/day | 1.11 | 0.91, 1.35 | .3 |

| 7 to 13.99 mL/day | 1.28 | 1.00, 1.64 | .05 |

| 14 to 20.99 mL/day | 1.43 | 1.08, 1.88 | .01 |

| 21 mL/day or more | 1.06 | 0.83, 1.36 | .6 |

Field center was included in the model. HS: High school.

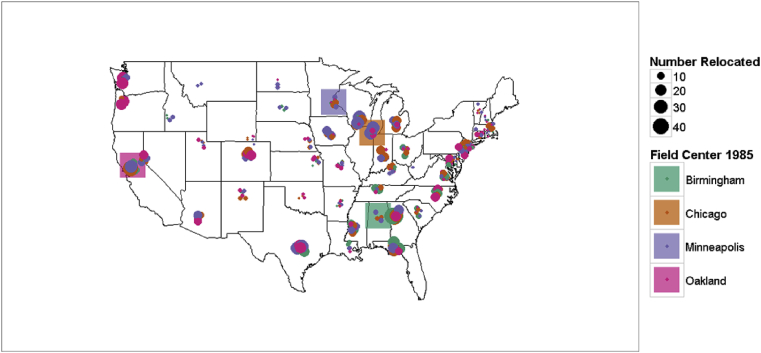

By the Y25 examination, participants were living in all 50 states (Fig. 1), including Hawaii and Alaska, and in 15 countries in the Caribbean and on four continents: Europe (England, France, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Czechoslovakia), Asia (Japan, Singapore, Thailand), Africa (Egypt, Ghana), South America (Brazil), North America (Canada), and the Caribbean (Bermuda, West Indies).

Fig. 1.

Location of CARDIA participants at time of Y25 examination according to field center of origin.

4. Discussion

We report here on retention strategies and predictors of long-term retention in one of the longest-running U.S. observational cohort studies. In conducting any long-term follow-up study, frequency of participant contact is critical. Contacting too frequently is not only costly in terms of staff time, but can be counterproductive if participants view this as harassment, leading to poorer cooperation and retention. Contacting too infrequently can also result in loss of participants, either through not being able to locate participants or participants losing interest.

The balance CARDIA has chosen is two contacts per year. The mid-year contact obtains verification of vital status and participant address status, and can be completed by a proxy, not requiring direct participant contact. Unlike studies with no corresponding examination component, such as the Nurses' Health Study [10] and Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study [11], CARDIA's model for annual contact serves two purposes: direct health status assessment and retention tracking for future clinic visits. Independent of examination retention, CARDIA has maintained an 83–94% retention rate across race-sex groups and field centers for any two-year period and 88–95% retention rates between examinations since the study began in 1985. This high contact rate between examinations means participants are available for future clinic visits and to provide endpoint data, even if they have not attended all in-person examinations. Our data also suggest that attending every clinic visit is not necessary for long-term retention.

Demographics of the study population, namely, age, race, sex and education, should be considered in assessing retention strategies and rates as they have been consistently associated with participation and retention. Almost all studies have found higher participation and retention among whites and the more educated [4,12], as did CARDIA [9]. The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study [4], ages 45–64 years in 1987, reported a 24-year overall examination retention rate of 65% that was higher for women than men (68% vs. 63%). In CARDIA, retention was also higher for women than men at 25 years, 74% vs. 70%. CARDIA found that not smoking and moderate alcohol intake were associated with greater 25-year retention. How these demographics influence retention is unclear, but are probably related to socioeconomic status, health status, and mobility as well as our retention strategies.

CARDIA reported better participation and retention among older participants, although they were still relatively young at 43–55 years. In the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), which followed adults ages 65 and older annually for 10 years starting in 1989 and then again starting in 2005, the ‘younger’ group, ages 65–69 years, had the best examination attendance [3]. The CHS found, as have most others, that retention rates were better for whites and the more educated [3]. ARIC [4] found little difference in initial participation by age, but like CHS, found better retention among the ‘younger’ participants, potentially due to health issues in the older group.

CARDIA has seen participants from young adulthood, when many are finishing education, transitioning from living with parents to independent living, getting married, having children, and starting new careers. This age range, when participating in a study may be considered a low priority, highlights the success CARDIA has had with retention. As an example of the cohort's mobility, by 2014, about 25% of CARDIA participants lived in a different state than when they enrolled. We have also kept contact with participants in and out of prison, through military service, and changes such as marriage, divorce, having children, and loss of loved ones.

CARDIA examinations require in-person attendance, which is costly but allows longitudinal clinical data to be collected in a standardized manner [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. While, in general, participation rates in epidemiologic and health studies have declined substantially in the past two decades [17], CARDIA has maintained high and consistent retention rates due to its retention strategies and contact frequency.

Our study is limited in that participants were not randomized to a specific retention method and may have been contacted by multiple strategies across time. Therefore, we were unable to test specific methods used to contact or collect information from them and compare characteristics of participants requiring or responsive to specific retention methods. This is a difficulty inherent to all long-standing cohort studies. Cohort members are not replaceable, and investigators rely on every available method possible, balanced against contacting too often. Thus, we cannot say definitively that every method used is needed to achieve the retention rates we have achieved. While the strategies and risk factors associated with better attendance are not used on every member of the cohort, having multiple strategies provides us with an array of tools. Our participants vary greatly by demographics and socioeconomic status, and therefore an approach that works best for one demographic group may not be successful for another group.

5. Conclusions

The varied methods CARDIA has used have been successful in retaining distinct members of our cohort, with a balance of providing participants with medically useful data and collecting data to improve the health of future generations. However, despite initial feasibility concerns about retaining young adults for a long-term study, we have demonstrated that not only is excellent retention possible, but that participants can be successfully followed for decades.

Disclaimer Statement

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C & HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C) and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005).

Acknowledgments

Authors want to thank the following field centers' staffs for their efforts in cohort retention and review of this manuscript: Julia H. Wilkoff, Carol A. Collier and J. Phillip Johnson at Birmingham; Kathleen I. Beck and Shirlee A. Mohiuddin at Chicago; Mary Zubrzycki, Jennifer J. Zahn and Candy M. Scott at Minneapolis; and Melissa L. Nelson and Kathleen R. Sampel Morris at Oakland.

Contributor Information

Ellen Funkhouser, Email: emfunk@uab.edu.

Jennifer Wammack, Email: jwammack@uab.edu.

Cathy Roche, Email: croche@uab.edu.

Jared Reis, Email: reisjp@nhlbi.nih.gov.

Stephen Sidney, Email: steve.sidney@kp.org.

Pamela Schreiner, Email: schre012@umn.edu.

Appendix A.

CARDIA 282-month participant satisfaction questionnaire

What did you like best about past CARDIA exams? Well organized – got in and out; flexible scheduling; staff (nice, courteous, professional, friendly); ability to see health information and changes over time; completeness/thoroughness of exam.

What would you like to see as part of this examination that you have not seen in the past? Better lunch; study on cancer (colon/prostate); MRI; more focus on bone-density issues; send out a dietary questionnaire ahead of time; hold clinics at other locations/traveling clinics/home visits; greater incentives (more money) for completion; shorter exam day.

What will make you most likely to attend this examination? Enjoy being part of study; pay more money; seeing staff again/like a reunion; concern about health/family history of heart disease; looking at trends and early warning; ticket/travel expenses; if in town would attend all; didn't have to pay for it/free testing; to get the checkup/complete physical; retired now – can do these things.

If you have been unable to attend some of the past examinations, what were the major reasons? Disabled now from stroke – harder to get around; work; scheduling; in a group home/incarcerated; out of town/overseas/deployed; hadn't taken time; finances.

Appendix B.

Abbreviated year 25 examination component priority levels

Priority ranking of components for abbreviated examination components are decided by the CARDIA Steering Committee a priori, and completed in order with whatever time the participant has available. Priority levels are based on both importance for cross-sectional associations and study hypotheses, and for longitudinal data trends. The goal is to complete all examination components, but particularly as the examination cycle is ending, abbreviated examinations become a way to capture some participant clinical data.

| Priority Level 1 |

| Consent |

| Exit Interview |

| Blood pressure |

| Laboratory—fasting phlebotomy and urine collection |

| Anthropometry |

| Medical History Questionnaire |

| Interim Health Care Contact Questionnaire |

| Socio-demographic Questionnaire |

| Tobacco Use Questionnaires |

| Priority Level 2 |

| Echocardiogram |

| Laboratory—Oral glucose tolerance test |

| Priority Level 3 |

| Family History Questionnaire |

| Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| Alcohol Use Questionnaire |

| Priority Level 4 |

| Medical History follow-up questionnaires: for Medications, Aspirin, Ovarian Surgery and pregnancy Questionnaires |

| Cognitive function battery |

| Women's Reproductive Health Questionnaire |

| Non-Medical Drug Use Questionnaire |

| Weight History Questionnaire |

| Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire |

| CES-Depression Questionnaire |

| Discrimination Questionnaire |

| Chronic Burden Questionnaire |

| Quality of Life SF-12 Questionnaire |

| Social Network Questionnaire |

| Beverages Questionnaire |

| Diet Practices Questionnaire |

| Weight Change Questionnaire |

References

- 1.Cutter G.R., Burke G.L., Dyer A.R. Cardiovascular risk factors in young adults. The CARDIA baseline monograph. Contr. Clin. Trials. 1991;12(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(91)90002-4. 1S-77S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudley J., Jin S., Hoover D. The multicenter AIDS cohort study: retention after 9 1/2 years. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995;142(3):323–330. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strotmeyer E.S., Arnold A.M., Boudreau R.M. Long-term retention of older adults in CHS. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010;58(4):696–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC). Cohort characteristics. ARIC Visit 5 Recruitment and Data Management Report. http://www2.cscc.unc.edu/aric/. Published February 26, 2014. (Accessed 1 September 2014).

- 5.Iannaccone C.K., Fossel A., Tsao H. Factors associated with attrition in a longitudinal rheumatoid arthritis registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(7):1183–1189. doi: 10.1002/acr.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teixeira P.J., Going S.B., Houtkooper L.B. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2004;28(9):1124–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson K.A., Dennison C.R., Wayman D.M. Systematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participants. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007;60(8):757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booker C.L., Harding S., Benzeval M. A systematic review of the effect of retention methods in population-based cohort studies. BMC Publ. Health. 2011;11:249. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman G.D., Cutter G.R., Donahue R.P. CARDIA: study design, recruitment and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stampfer M.J., Colditz M.B., Willett W.C. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy an cardiovascular disease: ten-year follow-up from the Nurses' health study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325(11):756–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109123251102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard V.J., Cushman M., Pulley L. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–143. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson R., Chambless L.E., Yang K. Differences between respondents and nonrespondents in a multicenter community-based study vary by gender ethnicity. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1441–1446. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs D.R., Jr., Yatsuya H., Hearst M.O. Rate of decline of forced vital capacity predicts future arterial hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):219–225. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.184101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xun P., Liu K., Cao W. Fasting insulin level is positively associated with incidence of hypertension among American young adults: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1532–1537. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee D.H., Steffes M.W., Gross M. Differential associations of weight dynamics with coronary artery calcium versus common carotid artery intima-media thickness: the CARDIA Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;172(2):180–189. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr J.J., Nelson J.C., Wong N.D. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234(1):35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galea S., Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007;17(9):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]