Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer in the US. Despite evidence that screening reduces CRC incidence and mortality, screening rates are sub-optimal with disparities by race/ethnicity, income, and geography. Rural-urban differences in CRC screening are understudied even though approximately one-fifth of the US population lives in rural areas. This focus on urban populations limits the generalizability and dissemination potential of screening interventions.

Methods

Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles, we designed a cluster-randomized trial, adaptable to a range of settings, including rural and urban health centers. We enrolled 483 participants across 11 health centers representing 2 separate networks. Both networks serve medically-underserved communities; however one is primarily rural and one primarily urban.

Results

Our goal in this analysis is to describe baseline characteristics of participants and examine setting-level differences. CBPR was a critical for recruiting networks to the trial. Patient respondents were predominately female (61.3%), African-American (66.5%), and earned <$1200 per month (87.1%). The rural network sample was older; more likely to be female, white, disabled or retired, and have a higher income, but fewer years of education.

Conclusions

Variation in the samples partly reflects the CBPR process and partly reflects inherent differences in the communities. This confirmed the importance of using CBPR when planning for eventual dissemination, as it enhanced our ability to work within diverse settings. These baseline findings indicate that using a uniform approach to implementing a trial or intervention across diverse settings might not be effective or efficient.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, Community-based participatory research, Health disparities, Medically underserved populations, Dissemination and implementation, Randomized trial

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States [1]. Routine screening and resultant early detection through a range of strategies (colonoscopy, fecal testing, etc.) [2] are both effective and cost-effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality and improving survival. Five-year survival for localized CRC is around 90%, but is lower with later-stage detection [3]. CRC incidence and mortality rates have declined over the last few decades yet screening rates remain relatively low and improvement is needed. Only 59% of adults are up-to-date for CRC screening, well below the Healthy People 2020 target of 70.5% [3,4]. There are disparities in CRC screening, mortality, and survival by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors such as income and insurance [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]].

Much of what we know about CRC screening comes from research in urban areas [5,11]. While fewer studies have focused on rural areas, data suggest that some rural residents face CRC disparities, including higher CRC mortality than urban residents [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. Recent studies have shown that compared to urban residents, rural residents are less likely to have ever been screened for CRC [22] or to be up-to-date with screening guidelines [23]. However, few interventions have been designed for, evaluated in, or disseminated to rural settings. Rural residents and communities are particularly under-represented in research studies on CRC screening interventions. This may contribute to rural-urban CRC disparities [24].

To address the under-representation of CRC screening research and known screening disparities in rural settings, we designed an intervention trial to promote CRC screening in rural and urban federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). This trial was carried out as part of the Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities (PECAD), an NCI-funded Community Networks Program Center. We planned this as a practical clinical trial [25,26] that was grounded in CBPR [27]. CBPR is a collaborative research approach that allows for participation in all aspects of research by the community affected by the health issue being studied [28]. CBPR may be particularly useful when implementing evidence-based interventions to new settings. Essentially, our community partners were involved in determining every aspect of the study, including study design and planning, recruitment and data collection, as well as intervention selection and adaptation. The inherent differences across settings, particularly rural-urban differences, can make standardizing trial protocols and interventions challenging, but embracing these differences and enabling participation from both rural and urban settings may support successful recruitment, increase the likelihood of intervention success and sustainability, enhance generalizability of findings, and increase the potential for dissemination.

Our goal in this analysis is to describe baseline characteristics of networks and participants to quantify differences between the networks, including the differences in the CBPR related procedural and process factors and how those affected the conduct of the trial. Understanding site differences will allow us to adapt interventions to enable implementation and maximize dissemination. It also will help us adapt future trial procedures to be adaptable to heterogeneous settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a cluster randomized controlled study designed to increase the rate of CRC screening among patients at urban and rural FQHCs. As part of the CBPR approach, PECaD's colon cancer community partnership and the Disparities Elimination Advisory committee (DEAC), which both include community, clinical, and university representation, provided guidance in study design and planning. Health center administrations and primary care providers were involved in planning and implementing the study, including shaping strategies for recruitment and data collection at their sites, and selecting intervention strategies from a “menu” of evidence-based options. These strategies were then tailored to fit each intervention health center, based on discussions with center leaders and local health care providers regarding the logistics and feasibility of each intervention. All procedures and materials were approved by the University's Institutional Review Board and by the administration of each participating health network.

2.2. Study population and recruitment

Health centers (n = 11) were recruited on a rolling basis among FQHCs in metropolitan St. Louis and rural southeastern Missouri. To be included, health centers had to be willing to be randomized to the intervention or control group and to allow the research team access to managers/directors, patients, and providers. To evaluate the intervention, we recruited patients for a self-report baseline survey, with follow-up at 6- and 12-months post-baseline. Participants were eligible if they were English or Spanish-speaking, and age 49 or older. No other inclusion criteria were applied.

While geography (rural versus urban) was a primary defining difference between the two health networks, it was not the sole differentiating factor. To best acknowledge the multiple differences between networks, rather than reducing the networks to a single geographical difference, we chose to refrain from identifying them as “rural” and “urban” and instead label them as network A and network B.

Network A, in the rural area, had sites located an average of four hours from the study headquarters at the university. The administration requested that participants be recruited by mail, indicating that with small waiting areas and fewer patients per day, in-person recruitment would be inefficient and could create challenges for center staff. Through a Memorandum of Understanding, Information Technology specialists generated an automated query that selected patients seen at the health centers in the last 36 months who were English or Spanish speaking, had contact information listed, and were 49 years or older at the time of the query. This list was used to mail an IRB-approved study information sheet, survey invitation, and the option to complete the survey by mail, online, or by telephone.

Network B, in the urban area, had health centers close to the university offices (all practice sites were <6 miles away). The administration required that the study team recruit participants in-person from the health centers' lobbies. As instructed by the health center administration, research staff set up a table in the main waiting areas, and provided pamphlets and verbal information about the study to patients who indicated interest.

The resulting study population consisted of a total of 490 consented participants across 11 sites. Of those participants, 7 were excluded from the analysis (4 duplicate enrollments, 2 ineligible at baseline due to age, and 1 incomplete enrollment), leaving 483 participants for this baseline analysis. All participants received a $20 gift card for completing the baseline survey.

2.3. Participant survey

Survey items were drawn from pre-existing measures and items used in our prior studies. Where possible, standard measures from national surveys (e.g., HINTS, NHIS, BRFSS, and CAHPS Health Plan Survey) were used, with some modifications to fit the study and improve comprehension. The surveys were pretested internally for length, comprehension, and skip patterns.

2.3.1. Demographics

Relevant demographic measures included gender, month and year of birth (and age), race/ethnicity, monthly income, employment status, and years of education.

2.3.2. Health insurance and utilization

Participants were asked whether they had health insurance and type of insurance; whether they had a usual source of care; and number of visits to a doctor's office, emergency room, or urgent care in the last 12 months. We also asked whether they had delayed or not gotten care because of cost, lack of transportation, or because of the way they thought they would be treated.

2.3.3. CRC screening

Screenings for CRC with fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test (FOBT/FIT), sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy were assessed with measures based on Vernon et al. [29]. Participants were asked if they had ever had each test, when they completed their most recent test, if they knew when they were due for their next test, and, for FOBT and sigmoidoscopy, how many tests they had in the past five years.

Based on feedback from network A, we modified the survey slightly for participants from their sites. Specifically, staff at network A indicated that recruitment would be better for a self-administered multi-modal survey than for one that required completion by phone. They also requested a shorter survey with a lower reading level. Truncated versions of the survey were created for network A to reduce the reading level and to allow for self-administration by mail or internet. However, key measures analyzed here were asked the same of participants at each site.

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics from the baseline survey were calculated through SPSS. Bivariate associations were tested to determine differences in patient populations between the different health networks, using χ2 and t tests. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of CRC screening by network. Confounding was explored by adding variables individually and in combination to the logistic regression models and then comparing the resulting point estimate for network status to a model including only network status. Variables that shifted the point estimate by >5% for most outcomes were retained in the model. We considered potential confounders in three categories: 1) those whose distributions may have been influenced by the CBPR process at each network, particularly the mailed surveys (e.g., age and sex); 2) those that differ inherently between rural and urban locations in Missouri (e.g., race); and 3) those typically associated with screening (e.g., insurance and having a regular doctor). Records with missing data, reported as “don't know” or “refused” were not included in these analyses (n = 474, 98.1% in the final sample). Sensitivity analysis was conducted, excluding the participant who was >85 and therefore not age-eligible for CRC screening. The results did not change the direction of significance thus we report the whole-sample findings.

3. Results

Participants in this study were recruited from health centers within two separate networks, one urban and one rural. Our goal in this analysis was to describe the baseline characteristics of participants and settings, as well as differences across networks. Even though one network was rural and one was urban, we refer to these health networks as network A and network B because the differences between the two networks and the study samples extend deeper than geographic location.

3.1. Setting characteristics

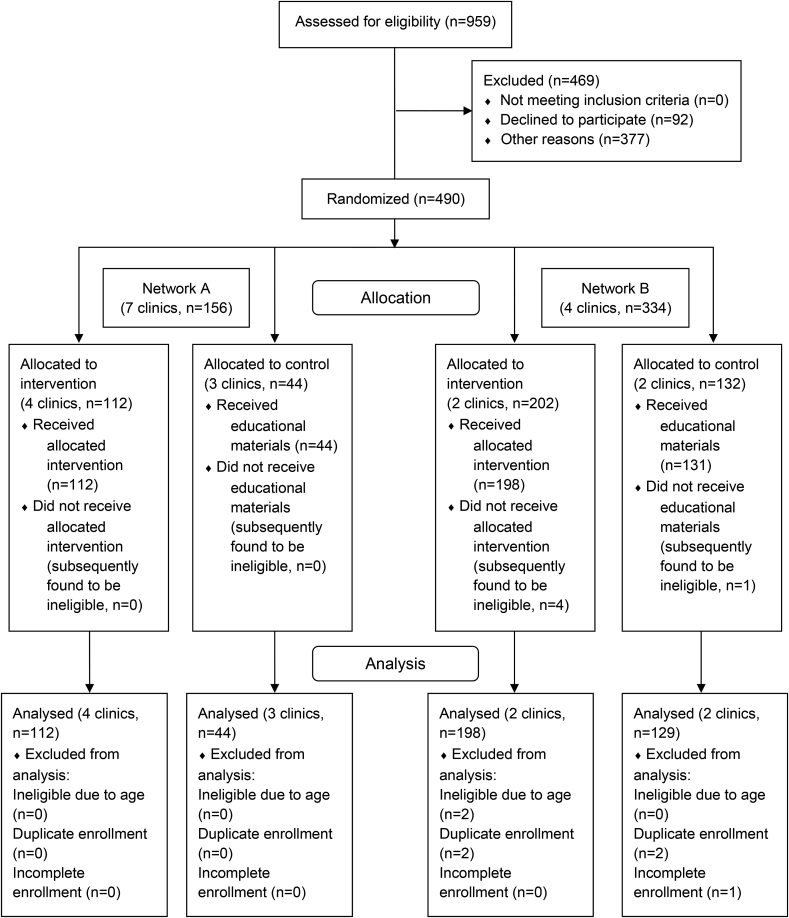

Fig. 1 shows the CONSORT diagram detailing participant recruitment. Table 1 describes the setting-level differences behind the participatory processes utilized in this study and the setting-level differences in the study procedures between the health networks. Network A was a new research partner with no previous research experience with the University. This system consisted of 7 separate centers with an average distance of 175.3 miles from research study staff. These centers were spread across a rural area, and were approximately 45.0 miles from each other. Health center administration advised that they used FOBT as their primary CRC screening method. During the CBPR process, this center requested that the study team extend the survey invitation to their patients via mailed letters. Initially 625 patients at network A were invited to participate in the study. Seven were deceased (indicated by returned mail), 92 declined enrollment, 294 did not respond, 76 letters were returned to sender, with 156 completing the baseline survey. Of 156 respondents, 141 completed the survey by mail, 14 by telephone, and 1 completed the survey online. Each version of the survey for network A used the same wording.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 1.

Setting-level differences behind the participatory process of a randomized control trial to increase colorectal cancer screening in medically-underserved populations.

| Health Network A (rural) | Health Network B (urban) | |

|---|---|---|

| Previous Research Experience | New partnership | Existing partnership, previous site of study recruitment |

| Preferred Patient Recruitment Method (as determined by community partners) | Provided contact information of eligible patients, survey invitations mailed to eligible patients | In-person, no patient information provided |

| Preferred Data Collection Method (as determined by community partners) | Mail, with phone calls as necessary for follow-up | In-person, with phone calls for follow-up surveys |

| Number of health centers | 7 | 4 |

| Average distance from research staff | 175.3 miles | 5.3 miles |

| Average distance between health centers | 45.0 miles | 4.8 miles |

| Initial response rate | 25% (156/625) | Unable to calculate |

| Preferred CRC screening method | FOBT | Colonoscopy |

Publicly available data from Health Resources & Service Administration's (HRSA) Health Center Program show that the majority of Network A's patient population is Non-Hispanic White (70.6%), with 88.8% having incomes at or below 200% of poverty and 49.3% with incomes at or below 100% of poverty [30]. Of their total patients 31.4% were uninsured and 49.6% publicly insured through Medicaid and/or Medicare [30]. For CRC screening, 21.8% were reported as up-to-date with CRC screening guidelines [30].

Network B had an existing partnership with the university research team and had been a recruitment site for previous studies. This system consisted of 4 separate centers in an urban area, with an average distance of 5.3 miles from research study staff and all were relatively close to each other (average distance < 5 miles). The health center administration advised that their providers relied more on colonoscopy as opposed to other modalities of CRC screening. At network B, 327 participants were recruited in person at the health center and completed the survey. Because the recruitment approach relied heavily on participants approaching the study staff to demonstrate interest and we were unable to assess eligibility status of those who did not approach, we are unable to calculate a response rate.

HRSA data show that the majority of their patient population is African American (72.0%), with 99.8% having incomes at or below 200% of poverty and 96.0% with incomes at or below 100% of poverty [31]. Of their total patients 52.4% were uninsured and 40.9% publicly insured through Medicaid and/or Medicare [31]. For CRC screening, only 13.1% reported being up-to-date with CRC screening guidelines [31].

3.2. Demographic characteristics and healthcare utilization of the study population

The mean age for the overall sample (N = 483) was 57 years (range 49–88), 61.3% were female, 66.5% were African American, 87.1% reported a monthly income below poverty, 31.2% had not finished high school, and 68.5% were unemployed or disabled (Table 2). The majority of respondents (80.9%) reported having a particular health care provider, and 46.1% had visited the ER or urgent care in the past 12 months. Most (71.6%) reported having health insurance, of which 89.4% had solely public insurance. Most of the population had been screened for CRC (65.2%) in the past, most commonly with colonoscopy (50.6%), followed by FOBT (37.7%) and sigmoidoscopy (10.4%). Only 46.3% were up-to-date with any CRC screening per current guidelines (limited to adults age <85; n = 482) (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and healthcare utilization of participants in a randomized control trial to increase colorectal cancer screening in medically-underserved populations.

| Overall | A | B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) |

483 |

156 (32.3) |

327 (67.7) |

|

|

Mean (SD) Range |

Mean (SD) Range |

Mean (SD) Range |

p |

|

| Age (mean (SD), range) |

57.30 (7.03) 49-88 |

62.31 (7.64) 50-88 |

54.91 (5.26) 49-79 |

<.001 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 38.7 | 21.2 | 47.1 | |

| Female | 61.3 | 78.8 | 52.9 | <.001 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 33.5 | 75.8 | 13.4 | |

| African American | 66.5 | 24.2 | 86.6 | <.001 |

| Monthly Income (%) | ||||

| < $1200 | 87.1 | 80.4 | 90.2 | |

| ≥ $1200 | 12.9 | 19.6 | 9.8 | <.001 |

| Education Completed (%) | ||||

| Did not finish HS | 31.2 | 37.7 | 28.1 | |

| HS graduate/GED | 40.2 | 39.7 | 40.4 | |

| More than HS | 28.7 | 22.5 | 31.5 | <.001 |

| Employment Status (%) | ||||

| Employed | 21.8 | 23.0 | 21.2 | |

| Unemployed | 26.4 | 11.2 | 33.4 | |

| Retired | 9.8 | 18.4 | 5.8 | |

| Disabled | 42.1 | 47.4 | 39.6 | <.001 |

| Insurance (currently covered, %) | 71.6 | 76.9 | 69.0 | .072 |

| Public only (of those insured, %) | 89.4 | 85.3 | 91.5 | .082 |

| Particular health care provider (%) | 80.9 | 92.4 | 75.8 | <.001 |

| Visited ER/urgent care (%) | 46.1 | 33.5 | 52.0 | <.001 |

| Needed care but didn't get it … (%) | 40.6 | 34.6 | 43.4 | .065 |

| …due to cost | 31.8 | 26.6 | 34.3 | .094 |

| …due to treatment | 13.1 | 9.8 | 14.7 | .141 |

| …due to transportation | 20.4 | 11.1 | 24.8 | .001 |

| Comfortable discussing CRC (%) | ||||

| Not at all/Somewhat | 19.2 | 22.4 | 17.8 | |

| Very/Extremely | 80.8 | 77.6 | 82.2 | .240 |

Bold text indicates a statistically significant difference with a p-value less than 0.05.

Table 3.

Screening utilization of participants in a randomized control trial to increase colorectal cancer screening in medically-underserved populations.

| Overall% | A% | B% | p | aORa | aORb | aORc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever had … | |||||||

| … FOBT | 37.7 | 70.9 | 22.4 | <.001 | 5.24 (3.21, 8.57) | 5.51 (2.97, 10.21) | 5.55 (3.36, 9.15) |

| … SIG | 10.4 | 20.1 | 6.2 | <.001 | 2.81 (1.39, 5.67) | 3.04 (1.28, 7.21) | 2.89 (1.43, 5.84) |

| … COL | 50.6 | 67.8 | 42.6 | <.001 | 1.74 (1.09, 2.77) | 2.12 (1.18, 3.81) | 1.86 (1.15, 3.01) |

| … ANY | 65.2 | 87.8 | 54.4 | <.001 | 2.91 (1.62, 5.21) | 3.63 (1.80, 7.34) | 3.28 (1.80, 6.00) |

| Up-To-Date … | |||||||

| … FOBT | 9.3 | 21.2 | 3.7 | <.001 | 5.44 (2.47, 11.99) | 5.26 (2.03, 13.60) | 5.53 (2.49, 12.30) |

| … SIG | 5.4 | 11.5 | 2.4 | <.001 | 4.20 (1.59, 11.11) | 4.90 (1.53, 15.70) | 4.65 (1.73, 12.50) |

| … COL | 40.4 | 55.8 | 33.0 | <.001 | 1.79 (1.14, 2.82) | 2.02 (1.15, 3.52) | 1.91 (1.20, 3.04) |

| … ANY | 46.4 | 66.0 | 37.0 | <.001 | 2.22 (1.40, 3.50) | 2.62 (1.48, 4.63) | 2.41 (1.50, 3.87) |

cOR = crude odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; FOBT = fecal occult blood test; SIG = sigmoidoscopy; COL = colonoscopy.

The reference category for all comparisons is Network B.

Bold text indicates a statistically significant difference with a p-value less than 0.05.

adjusted for age.

adjusted for age and race.

adjusted for age and insurance status.

3.3. Comparison of the study population by health network

A stratified analysis was conducted to examine whether there were differences between the two networks in sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare utilization, and CRC screening. Compared to participants from network B, the 156 participants from network A were older (mean age, 62 vs. 55), and more likely to be female (78.8% vs. 52.9%), white (75.8% vs. 13.4%), have an income over $1200 per month (19.6% vs. 9.8%), have a particular health care provider (92.4% vs. 75.8%), have any health insurance (76.9% vs. 69.0%), and among those insured, more likely to have private instead of public health insurance (14.7% vs. 8.5%, Table 2). Network B participants were less likely to have visited the ER or urgent care for their health care needs (33.5% vs. 52.0%) or to have put off seeking medical care because of transportation difficulties (11.1% vs. 24.8%, Table 2).

Participants at network A were also more likely to have ever been screened for CRC using any test (87.8% vs. 54.4%; OR = 6.04, 95% CI: 3.56–10.22), and to be up-to-date on their screening (66.0% vs. 37.0%; OR = 3.31, 95% CI: 2.22–4.94). These differences attenuated, but remained significant, after adjustment for age (OR: 3.13, 95% CI: 1.75, 5.60 for ever screening, OR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.39, 3.45 for up-to-date screening), and strengthened slightly after adjustment for race. Adjustment for insurance status also caused some estimates to attenuate or strengthen, but all remained statistically significant. Further adjustment for gender, income, education, employment status, having a particular doctor, visiting the emergency room or urgent care for healthcare needs, and putting off medical care due to transportation issues did not influence the estimates for ever or up-to-date screening (see Table 3).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this analysis was to identify differences between the two health networks that participated in the trial. In doing so, we aimed to validate the inclusion of diverse settings and the value of CBPR when striving for generalizability and maximizing dissemination potential. True to CBPR [[32], [33], [34]], we engaged community members (in this case, community clinicians) in a joint process across all phases of the research. We focused engagement efforts on clinicians and health center staff because the intervention was primarily aimed at health center environment, processes, and activities. Patients were represented in our project through our existing community partnerships – the Colon Cancer Community Partnership and the Disparities Elimination Advisory Committee. Each of these groups provided input and feedback during the development of the proposal and received regular updates on the project. We met with health center leaders and key representatives (as determined by the health centers themselves) to discuss the study and their interest in participating. To respect the already limited time and resources of health center personnel, we relied on the health center leaders to decide who should be involved in discussions regarding recruitment and data collection methods and met with these contacts as directed by our health center contact. Our community health center partners adapted the study methods to their network and participated fully in the development and planning of recruitment and data collection activities. We also allowed health centers to determine the extent of their involvement and time they dedicated to the process. This is particularly important in resource-limited settings like FQHCs where personnel may not have time to spare. Per the design, partners were able to select and modify intervention strategies, based on an evidence-based intervention “menu” presented to health center leaders by research staff that we jointly implemented at the centers randomized to the intervention condition. The objective was to implement strategies that would work in “real world” settings and test an intervention product that was feasible and appealing to participating sites, and could be disseminated in future studies. Below we highlight several “take-home” points from our study.

4.1. Using CBPR increased the diversity of the settings in which we implemented this trial

Two health networks, totaling 11 federally qualified health centers, agreed to participate. Both health networks are FQHCs that cater to medically underserved populations, the majority of whom live below the poverty level and are uninsured or under-insured. Network A was located in a rural setting, with seven small centers widely dispersed over four rural medically-undeserved counties that have well-documented and persistent economic and health disparities. This site is a new community partner, and many patients had not previously participated in research studies. The average distance of these centers from research staff in St. Louis was 175 miles. The distance made in-person visits challenging and participants might not have been familiar with the university's research efforts. Network B, in an urban setting near the university, has four centers within the city limits. The urban centers have a higher patient volume and the study team has partnered with these sites multiple times over the past several years. Patients at these sites were often familiar with the specialty medical services available from the Medical School and with research study participation.

4.2. Working with diverse settings, and the diverse patients within them, can increase potential for future dissemination

There were differences in demographic characteristics and healthcare utilization between the two networks. Network A showed a slightly older population, a higher proportion of respondents who were female, white, and who had not finished high school. They also had fewer participants who identified as unemployed, but more that identified as retired or disabled. The participants from the rural network A were more likely to have a usual health care provider and less likely to visit the emergency room or urgent care for their health care needs. This is perhaps due to the relative scarcity of urgent care and emergency services near their residences or the distances they had to travel to get there in this medically underserved region. Rural participants were less likely to mention putting off getting health care due to lack of transportation compared to the urban participants. This may reflect differences in the accessibility of primary and specialty care in rural versus urban settings or the availability of personal modes of transportation. Additionally, the results showed that compared to urban areas, in rural sites, FOBT was more common than colonoscopy, which was consistent with what the network administration had indicated. This, too, may be associated with availability or accessibility of specialty care, including colonoscopies [14,17,23]. Again, differences in participants across sites go deeper than geographic labels of rural and urban, but these contexts cannot be ignored. CBPR and adaptable procedures enhanced our ability to embrace and work with these differences.

4.3. The participatory process – allowing health centers to have a voice in the procedures-allowed us to successfully develop a new research collaboration with the rural network, improve the representation of rural patients in our study, and work toward reducing the research gap in rural screening interventions

Without using CBPR and without allowing adaptation, we risk having sites decline participation when the procedures are not acceptable or compatible with local context. With an increasing national emphasis on dissemination of evidence-based practices, interventions – and the trials that generate evidence - must be adaptable and flexible to fit the needs of diverse settings. The “one size fits all” approach may not be efficient or effective across settings and may, in fact, exclude some settings from being represented in research.

Adaptations amongst sites included method of recruitment and data collection to best fit not only the health center context but the patient population as well. Rural sites preferred a mail-based approach while the urban network felt that would not be effective. Our CBPR-grounded approach allowed us to embrace these differences rather than avoid them.

Working with the network to tailor the study procedures and intervention to the sites increased the chance that we could successfully recruit respondents but also that we could select and implement a sustainable intervention strategy. Because the intervention comparisons will control for the clustered trial design, between-network differences do not hinder our ability to evaluate intervention impact and thus remain a strength rather than a limitation.

4.4. There are challenges and limitations to integrating CBPR approaches into randomized intervention trials

We observed higher than expected CRC screening rates, perhaps due to our recruitment or data collection (self-report survey) methods. While only about half of survey respondents were “up-to-date” on screening (consistent with data reported by NCI and CDC through the State Cancer Profiles), we expected this to be lower given the under-served and economically disadvantaged characteristics of the population. We also did not expect CRC screening rates for rural participants to be higher than urban participants. However, with differing recruitment strategies at the two networks, the mailed survey invitation may have been more appealing to people already familiar with CRC screening or to certain demographics. On the other hand, the in-person recruitment and data collection at network B would have reached only those persons who had reason to be in the health center on a day when study staff were there recruiting. While we varied the days and times of recruitment, this remains a limitation. Natural differences between the networks could also have contributed to these variations. The patient-level differences by health network described here cannot be attributed just the differences to either population differences or to CBPR differences – it is a product of both.

5. Conclusions

These results add to our understanding of the value of integrating CBPR with randomized intervention trials, and the impact on generalizability and potential for dissemination. The application of CBPR enhanced our ability to recruit diverse sites and to recruit diverse patients within those sites. This is consistent with other authors who have reported benefits of bringing CBPR into clinical research. Greiner and colleagues examined data from several Community Network Program Center sites, and reported that following CBPR principles was associated with low study refusal and higher accrual [35]. Others have reported similar findings [36]. Similarly, a systematic review of 19 articles suggested that CBPR can enhance accrual of under-represented patients into clinical trials but called for additional research [37]. The differences between networks in our study affirm the use of participatory and adaptive implementation strategies for research and intervention. The dissimilar preferences of networks for recruitment may reflect the concerns of working in medically underserved areas and the need for flexibility to bring diverse clinics into research activities. It reflects trust and communication between settings and university researchers. It is likely that the rural network would not have participated at all in the trial had we not listened to their preferences for recruitment and data collection and instead had required specific strategies. Similarly, our urban partners would not have agreed to mailing out study invitations, and maintained that would have been ineffective in a patient population with frequent address changes (which was supported by our data on frequent address changes). Overall, our rural network looked different from what was expected based on the existing literature, giving evidence that not all rural populations are alike and again emphasizing the importance of participatory approaches. Further research into urban-rural disparities will be useful in better understanding the needs of both communities and implementing trials and disseminating effective strategies for engaging diverse communities in research and reducing cancer burden. CBPR and other flexible, adaptive approaches can improve inclusion of currently under-represented settings and small populations into our evidence-base.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [NCI—U54CA153460, PI: Colditz; Sub – 7717, PI: James]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. Additional support for the investigators was provided by Siteman Cancer Center and the Barnes Jewish Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.ACS . 2015. ACS Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock E.P., Lin J., Liles E., Beil T., Fu R., O'Connor E., Thompson R.N., Cardenas T. 2008. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: an Updated Systematic Review. Rockville (MD) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACS . 2014. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC Cancer screening—United States, 2010. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1248–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albano J.D., Ward E., Jemal A., Anderson R., Cokkinides V.E., Murray T., Henley J., Liff J., Thun M.J. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99(18):1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkowitz S.A., Percac-Lima S., Ashburner J.M., Chang Y., Zai A.H., He W., Grant R.W., Atlas S.J. Building equity improvement into quality improvement: reducing socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer screening as part of population health management. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015;30(7):942–949. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3227-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use–United States, 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013;62(44):881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards B.K., Ward E., Kohler B.A., Eheman C., Zauber A.G., Anderson R.N., Jemal A., Schymura M.J., Lansdorp-Vogelaar I., Seeff L.C., van Ballegooijen M., Goede S.L., Ries L.A. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James A.S., Hall S., Greiner K.A., Buckles D., Born W.K., Ahluwalia J.S. The impact of socioeconomic status on perceived barriers to colorectal cancer testing. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008;23(2):97–100. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07041938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I., Kuntz K.M., Knudsen A.B., van Ballegooijen M., Zauber A.G., Jemal A. Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012;21(5):728–736. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liss D.T., Baker D.W. Understanding current racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States: the contribution of socioeconomic status and access to care. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;46(3):228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNeill L.H., Coeling M., Puleo E., Suarez E.G., Bennett G.G., Emmons K.M. Colorectal cancer prevention for low-income, sociodemographically-diverse adults in public housing: baseline findings of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Publ. Health. 2009;9:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins A.S., Pavluck A.L., Fedewa S.A., Chen A.Y., Ward E.M. Insurance status, comorbidity level, and survival among colorectal cancer patients age 18 to 64 years in the National Cancer Data Base from 2003 to 2005. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(22):3627–3633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabatino S.A., White M.C., Thompson T.D., Klabunde C.N. Cancer screening test use - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015;64(17):464–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steel C.B., Rim S.H., Joseph D.A., Kind J.B., Seeff L.C. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening - United States, 2008-2010. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR Weekly) 2013;62(3):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James T.M., Greiner K.A., Ellerbeck E.F., Feng C., Ahluwalia J.S. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherence. Ethn. Dis. 2006;16(1):228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aboagye J.K., Kaiser H.E., Hayanga A.J. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):537–543. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole A.M., Jackson J.E., Doescher M. Colorectal cancer screening disparities for rural minorities in the United States. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2013;4(2):106–111. doi: 10.1177/2150131912463244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis T.C., Rademaker A., Bailey S.C., Platt D., Esparza J., Wolf M.S., Arnold C.L. Contrasts in rural and urban barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am. J. Health Behav. 2013;37(3):289–298. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.3.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young W.F., McGloin J., Zittleman L., West D.R., Westfall J.M. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural Colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J. Rural Health. 2007;23(3):238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahnd W.E., James A.S., Jenkins W.D., Izadi S.R., Fogleman A.J., Steward D.E., Colditz G.A., Brard L. Rural-urban differences in cancer incidence and trends in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojinnaka C.O., Choi Yong, Kum Hye-Chung, Bolin Jane N. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening: does rurality play a role? J. Rural Health. 2015;31(3):254–268. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson A.E., Henry K.A., Samadder N.J., Merrill R.M., Kinney A.Y. Rural vs urban residence affects risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;11(5):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baquet C.R., Ellison G.L., Mishra S.I. Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in National Cancer Institute-supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(2 Suppl):120–134. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow R.E., Davidson K.W., Dobkin P.L., Ockene J., Spring B. Practical behavioral trials to advance evidence-based behavioral medicine. Ann. Behav. Med. : a Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2006;31(1):5–13. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tunis S.R., Stryer D.B., Clancy C.M. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James A.S., Richardson V., Wang J.S., Proctor E.K., Colditz G.A. Systems intervention to promote colon cancer screening in safety net settings: protocol for a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Implement. Sci. 2013;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viswanathan M., Ammerman A., Eng E., Garlehner G., Lohr K.N., Griffith D., Rhodes S., Samuel-Hodge C., Maty S., Lux L., Webb L., Sutton S.F., Swinson T., Jackman A., Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2004;99:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vernon S.W., Meissner H., Klabunde C., Rimer B.K., Ahnen D.J., Bastani R., Mandelson M.T., Nadel M.R., Sheinfeld-Gorin S., Zapka J. Measures for ascertaining use of colorectal cancer screening in behavioral, health services, and epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004;13(6):898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.2014-2016 Southeast Missouri health network, inc. Health center profile. 2016. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=d&state=MO&year=2013&bid=071370#

- 31.2014-2016 Affinia healthcare health center profile. 2016. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=d&state=MO&year=2013&bid=071190

- 32.Israel B.A., Krieger J., Vlahov D., Ciske S., Foley M., Fortin P., Guzman J.R., Lichtenstein R., McGranaghan R., Palermo A.G., Tang G. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J. Urban Health : Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel B.A., Parker E.A., Rowe Z., Salvatore A., Minkler M., Lopez J., Butz A., Mosley A., Coates L., Lambert G., Potito P.A., Brenner B., Rivera M., Romero H., Thompson B., Coronado G., Halstead S. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the centers for Children's environmental health and disease prevention research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J. Urban Health : Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2005;82:ii3–ii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. 2 Suppl 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greiner K.A., Friedman D.B., Adams S.A., Gwede C.K., Cupertino P., Engelman K.K., Meade C.D., Hebert J.R. Effective recruitment strategies and community-based participatory research: community networks program centers' recruitment in cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014;23(3):416–423. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanza M.M., Goodson M., Osman A., Porraz Capetillo M.D., Hared A., Nigon J.A., Meiers S.J., Weis J.A., Wieland M.L., Sia I.G. Lessons learned from community-led recruitment of immigrants and refugee participants for a randomized, community-based participatory research study. J. Immigr. Minority Health. 2016;18(5):1241–1245. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0394-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De las Nueces D., Hacker K., DiGirolamo A., Hicks L.S. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv. Res. 2012;47:1363–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01386.x. 3 Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]