Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (SIJF) has become an increasingly accepted surgical option for chronic sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction, a prevalent cause of unremitting low back/buttock pain.

Objective

The objective of this study was to report clinical and functional outcomes of SIJF using triangular titanium implants (TTI) in the treatment of chronic SI joint dysfunction due to degenerative sacroiliitis or sacroiliac joint (SIJ) disruption at 3 years postoperatively.

Methods

A total of 103 subjects with SIJ dysfunction at 12 centers were treated with TTI in two prospective clinical trials (NCT01640353 and NCT01681004) and enrolled in this long-term follow-up study (NCT02270203). Subjects were evaluated in study clinics at study start and again at 3, 4, and 5 years.

Results

Mean (SD) preoperative SIJ pain score was 81.5, and mean preoperative Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was 56.3. At 3 years, mean pain SIJ pain score decreased to 26.2 (a 55-point improvement from baseline, p<0.0001). At 3 years, mean ODI was 28.2 (a 28-point improvement from baseline, p<0.0001). In all, 82% of subjects were very satisfied with the procedure at 3 years. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) time trade-off index improved by 0.30 points (p<0.0001). No adverse events definitely related to the study device or procedure were reported; one subject underwent revision surgery at year 3.7. SIJ pain contralateral to the originally treated side occurred in 15 subjects of whom four underwent contralateral SIJF. The proportion of subjects who were employed outside the home full- or part-time at 3 years decreased somewhat from baseline (p=0.1814), and the proportion of subjects who would have the procedure again was lower at 3 years compared to earlier time points.

Conclusion

In long-term (3-year) follow-up, minimally invasive trans-iliac SIJF with TTI was associated with improved pain, disability, and quality of life with relatively high satisfaction rates.

Level of evidence

Level II.

Clinical relevance

SIJF with TTI.

Keywords: sacroiliac joint fusion, chronic low back pain, multicenter study

Introduction

Non-autoimmune sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction is increasingly recognized as an important cause of chronic low back pain, with prevalence estimates of 15–30%1–5 and a known female predominance.6,7 SIJ pain reduces quality of life to an extent similar to other spine conditions.8,9 Nonsurgical treatments include physical therapy, chiropractic, intra-articular SIJ steroid injections, prolotherapy, and radiofrequency neurotomy of sacral nerve root branches. These treatments have some literature support,10–15 but high-quality evidence supporting long-term improvements is lacking.

Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (SIJF) is an increasingly accepted surgical option for SIJ dysfunction. To date, improvement in pain, disability, and quality of life has been demonstrated in three prospective clinical trials16–18 as well as numerous case series19–24 and comparative case series.25–27

Although multiple devices are now available for SIJF, the majority of reported literature describes the use of porous triangular titanium implants (TTI). Long-term studies reporting SIJF with TTI include a 3-year multicenter retrospective cohort,28 a 5-year single-center case series,29 and a 6-year comparative case series.30 The 6-year cohort included long-term follow-up in patients who were unable to undergo SIJF due to insurance coverage denials; this cohort showed worsened pain and disability scores, with worse working status and increased opioid use.

Long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in prospective clinical trials is a valuable but often challenging task. Herein, we report a prospective 3-year follow-up of subjects undergoing SIJF as part of two US prospective multicenter trials (Investigation of Sacroiliac Fusion Treatment [INSITE] and Sacroiliac Joint Fusion with iFuse Implant System [SIFI]). Follow-up is ongoing, and radiographic follow-up (with 5-year computed tomography [CT] scans) will be reported later.

Methods

Participants

Subjects included in this study (Long Term Outcomes from INSITE and SIFI [LOIS], NCT02270203) were enrolled at 12 centers who participated in either INSITE or SIFI. To participate, a site had to have enrolled and treated at least five patients with SIJF; have sufficient clinical trial resources, including a dedicated study investigator and coordinator who could carry out trial requirements; and the ability to maintain meaningful enrollment and follow-up for this long-term study. Of 39 sites participating in INSITE and SIFI, 12 sites met criteria of study participation. Participants were screened for study eligibility criteria and those not meeting all criteria (screen failures) or who refused participation were tabulated.

INSITE is a prospective multicenter randomized trial of SIJF vs. non-surgical management whose 2-year results showed high degrees of improvement in pain, disability, and quality of life in the surgical group but only modest responses in the non-surgical group.16 SIFI is a prospective multicenter single-arm clinical trial evaluating the same procedure/device; the follow-up schedule and assessments were nearly identical, and 2-year results were similarly positive.18 A pooled analysis of these trials (along with a randomized trial from Europe17) showed marked homogeneity of study results.31

INSITE/SIFI subjects at participating centers were approached regarding participation in LOIS. To qualify, a subject had to have undergone SIJF with TTI within the INSITE or SIFI studies and sign a LOIS-specific informed consent form. As reported previously, enrollment in INSITE and SIFI required a diagnosis of SIJ dysfunction due to degenerative sacroiliitis or SIJ disruption that included elements of history, a positive Fortin finger test,32 at least three positive physical examination signs suggestive of SIJ dysfunction, and a positive diagnostic SIJ block performed under fluoroscopic or CT guidance. Key exclusion criteria were severe low back or hip pain due to other conditions, SIJ dysfunction due to autoimmune or inflammatory conditions and osteoporosis.16,18

Interventions and assessments

Study follow-up in LOIS consists of phone calls postoperatively at years 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5 as well as in-clinic study visits at years 3, 4, and 5. Phone calls were intended to maintain subject contact and assess for adverse events. At in-clinic visits, subjects completed surveys to assess SIJ pain and low back pain scores (identical visual analog scale [VAS; 0–100 scale]), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), quality of life (EuroQol-5D [EQ-5D] time trade-off [TTO] index, a health state utility value ranging from <0 [death] to 1 [perfect health]), and satisfaction. All questionnaires were administered by trained study research coordinators.

Subjects were also queried regarding the occurrence of adverse events, defined using an international standard (ISO14155:2011). Both sites and study monitors also reviewed medical records to ensure complete adverse event reporting during follow-up study. For each event, the site investigator was required to assess severity and relatedness to their SIJF or preexisting condition. Relatedness to a device or procedure was characterized as definitely, probably, possibly, unlikely, or not related.

Herein, we report 3-year clinical, functional, and safety outcomes. The 5-year visit, which includes a high-resolution CT scan of the pelvis, will be reported elsewhere.

All centers obtained approval from applicable institutional review boards (IRB) (Table S1) for the extension study prior to participation. Subjects were recompensed nominal amounts for time and expense to complete study visit and call requirements, as approved by each site’s governing IRB. The study was sponsored by the device manufacturer (SI-BONE, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). All study sites underwent remote and regularly scheduled on-site data monitoring visits by sponsor representatives; all collected data were verified against source documents at the site.

The primary efficacy success end point for this study is a composite success end point at 3, 4, and 5 years defined as a reduction from preoperative VAS SIJ pain score of at least 20 points, absence of device-related serious adverse events, absence of neurological worsening, and absence of surgical revision. Note that the primary end point used was identical to that used in the component trials (INSITE and SIFI), where the primary clinical end points were evaluated at 6 months. Other outcomes included improvements in VAS SIJ pain score, ODI,33 EQ-5D score,34 proportion of non-working subjects who return to work, and occurrence of serious adverse events.

Statistical analysis

A standard approach to statistical analysis was used to calculate standard aspects of change scores and binary outcomes. Repeated measures analysis of variance, which simultaneously takes into account multiple measurements per subject, was used to determine statistical significance of changes from baseline, where relevant binary outcomes were measured with a chi-squared test, McNemar’s test, or exact binomial confidence intervals.

Results

Of 127 potentially eligible INSITE/SIFI subjects, 103 were enrolled in LOIS. Reasons for non-participation included inability to participate due to health issues (n=2), death prior to screening (n=3), lost to follow-up on previous study (n=4), moved out of state (n=1), refused study participation (n=11), planning pregnancy (n=1), previous withdrawal from INSITE or SIFI (n=1), and unlikely to be compliant (n=1). Of the 103 participating subjects, 96 (93%) subjects had 3-year follow-up visits. Reasons for lack of follow-up included loss to follow-up (n=5), death due to other causes (n=2), and withdrawal of consent (n=1).

All enrolled subjects met study eligibility criteria. There were no meaningful differences in baseline demographic characteristics for subjects enrolled in LOIS vs. those enrolled in the original trials (Table 1). Two-year responses to SIJF were slightly larger in subjects participating at LOIS sites compared to those who did not participate (improvement in VAS SIJ pain of 62.3 vs. 48.0 points, p<0.0001; improvement in ODI of 28.8 vs. 23.9 points, p=0.0776). There were no meaningful differences in the cohort enrolled versus subjects completing the 3-year visit (not shown). Subjects (mean age 51 years) were mostly Caucasians (97%) and female (73%). Subjects had high preoperative pain scores (mean [SD] of 81.5 [12.6]) and high levels of disability (ODI score 56.3 [12.1]). The duration of pain prior to enrollment averaged 5.7 years. EQ-5D at baseline was 0.45 (0.17), indicating a very poor quality of life.8 In all, 77% of subjects were taking opioids for back or SIJ pain preoperatively and 45% had a history of lumbar fusion, and concomitant spine and hip disease was common. Most (93, 90.3%) patients underwent unilateral SIJF on either of the treatment studies; 10 (9.7%) patients had qualifying pain, physical examination signs, and diagnostic blocks consistent with bilateral SIJ dysfunction and therefore underwent bilateral SIJF. Pain but not ODI scores between months 6 and 24 was slightly lower at sites that participated in the current study vs. those that did not (not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline and surgical characteristics of LOIS participants compared to original trials

| Characteristic | LOIS (n=103) | INSITE/SIFI (n=274a) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 50.8 (10.8) | 50.6 (11.3) | 0.7921 |

| Female, n (%) | 75 (72.8) | 195 (71.2) | 0.6812 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 31.0 (7.4) | 29.7 (6.5) | 0.0225 |

| Non-white race, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 11 (4.0) | 0.5439 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 3 (3.9) | 11 (4.0) | 0.5439 |

| History of prior lumbar fusion, n (%) | 46 (44.7) | 117 (42.7) | 0.6166 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 19 (18.4) | 70 (25.5) | 0.1128 |

| Pain began in peripartum period, n (%) | 14 (13.6) | 28 (10.2) | 0.3657 |

| Pain duration, years, mean (SD) | 5.7 (6.8) | 5.8 (6.9) | 0.8345 |

| VAS SIJ pain, mean (SD) | 81.5 (12.6) | 80.8 (12.5) | 0.4536 |

| ODI, mean (SD) | 56.3 (12.1) | 55.9 (12.0) | 0.7241 |

| EQ-5D TTO index, mean (SD) | 0.45 (0.17) | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.2405 |

| Surgical characteristics | |||

| Right side, n (%) | 42 (40.8) | 97 (56.7) | 0.0126 |

| Bilateral SIJF, n (%) | 10 (9.7) | 38 (13.9) | 0.1495 |

| Operative duration (minutes), mean (SD) | 46.3 (16.4) | 45.7 (20.0) | 0.8011 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 0.72 (0.93) | 0.83 (0.98) | 0.3124 |

| Number of implants, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 2 (1.9) | 9 (5.3) | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 80 (77.7) | 157 (91.8) | |

| 4 | 21 (20.4) | 5 (2.9) |

Notes:

172 subjects in SIFI+102 subjects in INSITE assigned to SIJF.

Comparing participants vs. non-participants.

Abbreviations: EQ-5D TTO index, EuroQol-5D time trade-off index; INSITE, Investigation of Sacroiliac Fusion Treatment; LOIS, Long Term Outcomes from INSITE and SIFI; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; SIFI, Sacroiliac Joint Fusion with iFuse Implant System; SIJF, sacroiliac joint fusion; SIJ, Sacroiliac Joint Pain; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

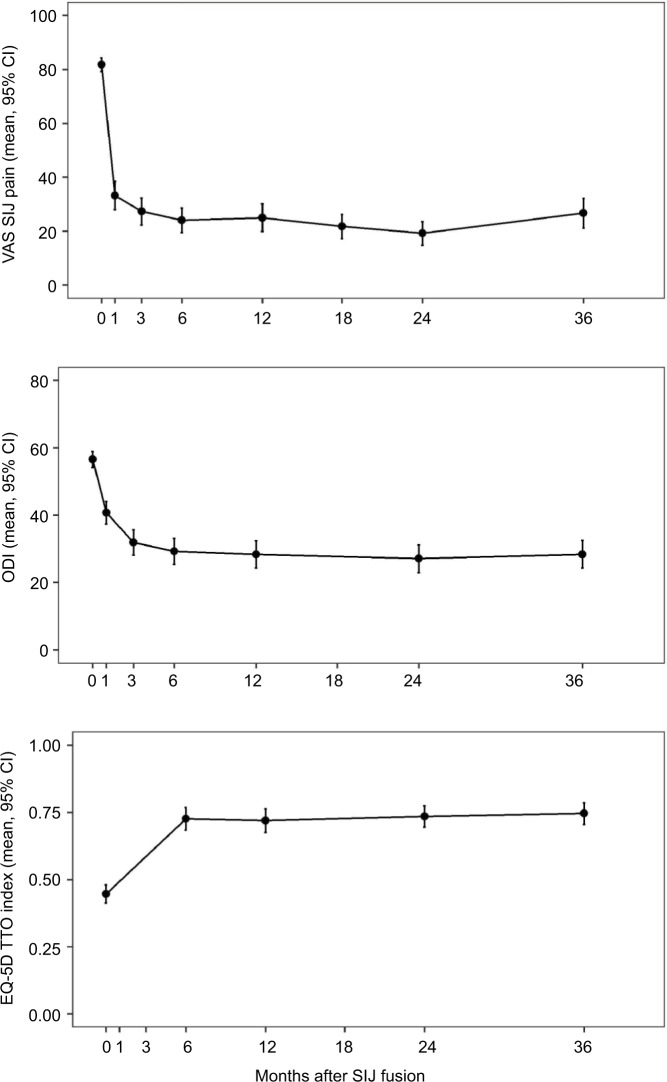

At 3 years, the mean SIJ pain score had decreased to 26.2, representing a mean change from preoperative score of 55 points (p<0.0001; Figure 1). In all, 71 (86%) subjects met the primary efficacy success composite end point. The mean ODI score decreased from 56 preoperatively to 28 at 3 years, an improvement of 28 points (p<0.0001). In all, 60 (72.3%) subjects had improvement in ODI scores of at least 15 points from their preoperative score. Compared to subjects who did not participate in this long-term follow-up study, participants in the current study had slightly larger 24-month improvements in SIJ pain and ODI (62.3 vs. 48.0 points, p<0.0001; improvement in ODI of 28.8 vs. 23.9 points, p=0.0776). Had all subjects in INSITE/SIFI participated, estimated responses over all follow-up would have been slightly smaller (by 8 or fewer points for VAS SIJ pain [0–100 scale] and 3.2 or fewer points for ODI). EQ-5D TTO index improved by 0.30 points (p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Mean VAS SIJ pain (top), ODI (middle), and EQ-5D (bottom) by time.

Note: Data from baseline through month 24 are from subjects’ participation in INSITE16/SIFI18.

Abbreviations: EQ-5D TTO Index, EuroQol-5D time trade-off index; INSITE, Investigation of Sacroiliac Fusion Treatment; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SIFI, Sacroiliac Joint Fusion with iFuse Implant System; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

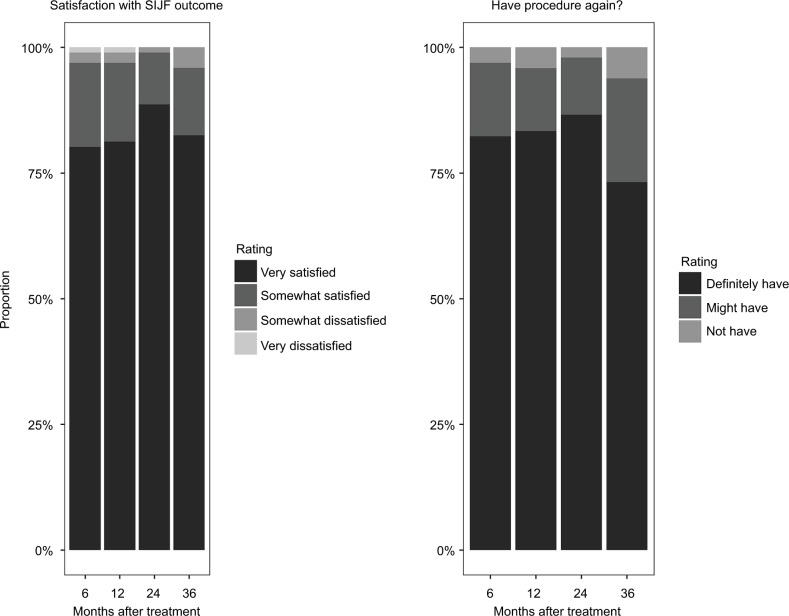

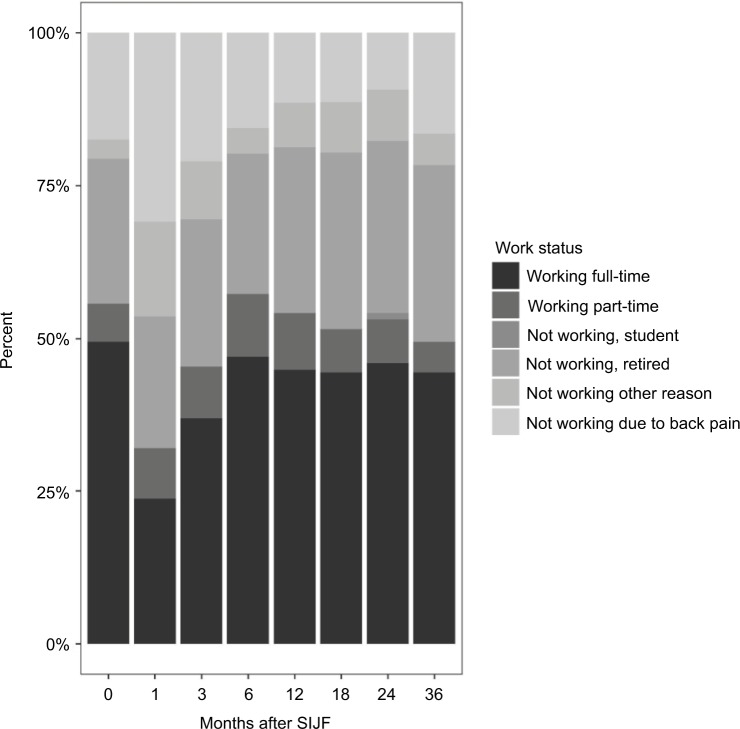

Satisfaction rates with the iFuse result were high (96% subjects were very or somewhat satisfied at 3 years; Figure 2). The proportion of patients who would definitely undergo the procedure again was high at 24 months (87%) and lower at month 36 (73%, p=0.003 for change from month 24 to month 36). Satisfaction rates correlated with improvement in SIJ pain and ODI. Work status (i.e., the proportion of subjects working full- or part-time outside the home) at 36-month follow-up was unchanged compared to baseline (McNemar p=0.1814; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Three-year ratings of satisfaction with outcomes of SIJF (left) and whether subjects would have procedure again (right).

Abbreviation: SIJF, sacroiliac joint fusion.

Figure 3.

Work status by months after SIJF.

Abbreviation: SIJF, sacroiliac joint fusion.

To date, 168 adverse events were reported in 75 subjects, most of which were unrelated to the pelvis or spine. Of the 22 events involving the pelvis, one involved bilateral SIJ pain, five reported ipsilateral SIJ pain, one was potentially related to the index SIJ and 15 reported SIJ pain contralateral to the index side. One subject, who experienced only modest temporary SIJ pain relief, underwent revision of the index side at year 3.7 at the subject’s request by a non-study physician. Imaging showed excellent device placement and no radiolucency; the investigator believed that progressive lumbar scoliosis contributed to the subject’s pain. Five subjects underwent treatment of contralateral SIJ pain with SIJF. No subject had an event rated as related to the iFuse implant or placement procedure. One subject had worsening lumbar facet pain rated as probably related to a non-surgical SIJ procedure. There were no severe device- or procedure-related adverse events.

Discussion

SIJ dysfunction markedly impacts quality of life8 and is potentially treatable with both non-surgical and surgical approaches. However, the condition is often overlooked as an etiology of axial back pain, primarily because, until recently, no surgical treatment had been shown to provide adequate long-term pain relief with an acceptable recovery profile. With the advent of minimally invasive SIJF, familiarity and interest in the condition have grown and specialty society guidelines are now available.35,36 Published literature confirming the safety and effectiveness of SIJF is expanding and now includes two prospective multicenter randomized trials,16,17 a prospective multicenter single-arm trial18 and multiple case series.19–30

Herein, we report 3-year follow-up of subjects who participated in two 24-month prospective multicenter US trials (one randomized trial16 and one prospective single-arm trial18). We observed ongoing improvements in SIJ pain, disability, and quality of life, which appear to be durable over time. These improvements were relatively large and similar to those observed in other commonly performed spine surgery procedures. Satisfaction rates were high, and very few patients had SIJ-related complaints that required surgical treatment. The proportion of subjects who stated they would definitely have the procedure again was significantly less at month 36 compared to month 24; the reason for this is not known. SIJF did not affect work status overall.

In all, 15% of subjects reported SIJ pain contralateral to the index side during the study. Our study cannot determine which of the following could pertain: 1) the same degenerative process that affected the index side affected the contra-lateral side; 2) the subject had bilateral pain at baseline with only one (the index) side qualifying for surgery within the study; 3) increased activity as a result of successful index side surgery may exacerbate the contralateral SIJ; or 4) fusion of the index side biomechanically accelerates degeneration of the contralateral side, a variant on adjacent segment degeneration. A biomechanical study showed that SIJF does not significantly alter the loading across the contralateral SIJ, suggesting no increase in the likelihood of adjacent segment degeneration.37 Our data provide little evidence that SIJF increases the risk of hip or lumbar spine pathology. One subject underwent revision surgery of the index side at his request by a non-study physician.

Our results are similar to those observed in several other retrospective case series,28–30 which have reported positive long-term (>24-month) outcomes. In a multicenter cohort, sustained positive outcomes and relatively low ODI scores were reported.28 A small cohort of patients at 5 years showed low pain scores and high rates of bony fusion.29 In a comparative cohort study conducted in Spain, patients who underwent SIJF demonstrated improvements in pain, disability, work status, and opioid use in comparison with patients undergoing continued conservative management who experienced worsened pain, disability, and work status as well as increased opioid use.30

Although the diagnosis of SIJ-mediated back/buttocks pain is often described as being challenging, our results suggest that SIJ dysfunction can not only be reliably diagnosed (through a combination of history, physical examination, and response to diagnostic SIJ block[s]) but also effectively treated.

The major advantage of this study is the prospective long-term follow-up of a relatively large number of subjects from a variety of treatment settings undergoing SIJF in two prospective clinical trials. The primary disadvantage is the lack of long-term data from a concurrent control group receiving only non-surgical treatment. In the INSITE study, most subjects in the non-surgical control group who experienced inadequate pain relief at month 6 crossed over to surgical care. However, long-term non-surgical follow-up appears to be associated with very poor outcomes.30 Another limitation is that several sites in INSITE and SIFI could not participate in the current study due to either low numbers of subjects or lack of clinical trial resources; subjects at participating sites had slightly larger 24-month improvements in SIJ pain and ODI compared to those at non-participating sites. The calculated impact on 3-year scores reported herein was small – approximately 4 points for VAS SIJ pain and 2.4 points for ODI. Another limitation is that the data from this study of triangular implants are not applicable to clinical outcomes from devices with other designs and fusion strategies for SIJF.

Conclusion

In this prospective study, improvements in pain, disability, and quality of life were sustained at 3 years after SIJF with TTI. Satisfaction rates were high.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

Institutional review boards that approved this study

| Site ID | Site name | Approving Institutional Review Board (IRB) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Columbia Orthopedics | Washington University St. Lois |

| 5 | Medical University of South Carolina | Medical University of South Carolina |

| 7 | Gordon Spine | Western IRB |

| 16 | Resurgens Orthopaedics | Western IRB |

| 27 | Orthopedics of Oklahoma | Western IRB |

| 35 | Orthopaedic Center of Southern Illinois | Western IRB |

| 36 | Integrated Spine Care | Wheaton Franciscan IRB |

| 38 | Yale University | Yale University IRB |

| 47 | Aurora BayCare Orthopedics | Western IRB |

| 48 | Bluegrass Orthopedics | Western IRB |

| 58 | Allegheny Medical Center | Western IRB |

| 60 | Overtake Hospital | Western IRB |

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to study subject recruitment and data collection: Don Kovalsky, MD, Cristy Buchanan, RT (Orthopaedic Center of Southern Illinois, Mount Vernon, IL, USA); Harry Lockstadt, MD, Elaine Wilhite, MS (Bluegrass Orthopaedics & Hand Care, Lexington, KY, USA); Clay Frank, MD, Tracy Mente, RN (Wheaton Franciscan Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA); Emily A. Darr, MD, Monica Baczko, Grayson McClam (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC); Abhineet Chowdhary, MD, Tina Fortney, RN, BSN (Overlake Medical Center, Bellevue, WA, USA); Andy Redmond, MD, Laurie Doredant, Beth Short, BSN, MS (Precision Spine Care, Tyler, TX, USA); S. Craig Meyer, MD, Michelle Vogt, RT (Columbia Orthopedic Group, Columbia, MO, USA); Peter G Whang, MD, Bethany Samperi (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA); Michael Y Oh, MD, Matt Yeager (Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA, USA); CL Soo, MD, Kallena Haynes, Julie White (Medical Research International, Oklahoma City, OK, USA); Robert Limoni, MD, Taylor Romdenne, BS, CCRP (Aurora BayCare Clinic, Green Bay, WI, USA); and Philip Ploska, MD, Terrell Price, PA-C (Regenerative Orthopaedics & Spine Institute, Stockbridge, GA, USA). The authors also acknowledge members of SI-BONE Clinical Affairs (Kathryn Wine, MPH, Elaine Wilhite, MS) for assistance with study conduct and monitoring.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

All authors conducted clinical research as part of prospective trials sponsored by SI-BONE. Peter G Whang, Philip Ploska, Harry Lockstadt, S Craig Meyer, and Clay Frank are paid consultants to SI-BONE. Daniel Cher is an SI-BONE employee. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bernard TN, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin Orthop. 1987;(217):266–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20(1):31–37. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maigne JY, Aivaliklis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21(16):1889–1892. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irwin RW, Watson T, Minick RP, Ambrosius WT. Age, body mass index, and gender differences in sacroiliac joint pathology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(1):37–44. doi: 10.1097/phm.0b013e31802b8554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sembrano JN, Polly DW. How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine. 2009;34(1):E27–E32. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818b8882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RSGM. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cher D, Polly D, Berven S. Sacroiliac Joint pain: burden of disease. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014;7:73–81. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S59437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cher DJ, Reckling WC. Quality of life in preoperative patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction is at least as depressed as in other lumbar spinal conditions. Med Devices (Auckl) 2015;8:395–403. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S92070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luukkainen R, Nissilä M, Asikainen E, et al. Periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in patients with seronegative spondylarthropathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17(1):88–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, Sanila MT, Asikainen EL. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(1):52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maugars Y, Mathis C, Berthelot JM, Charlier C, Prost A. Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: a double-blind study. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(8):767–770. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.8.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Buckenmaier CC, Kurihara C, Morlando B, Dragovich A. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(2):279–288. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f4c7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel N, Gross A, Brown L, Gekht G. A randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy of lateral branch neurotomy for chronic sacroiliac joint pain. Pain Med. 2012;13(3):383–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim WM, Lee HG, Jeong CW, Kim CM, Yoon MH. A randomized controlled trial of intra-articular prolotherapy versus steroid injection for sacroiliac joint pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(12):1285–1290. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, et al. Two-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion vs. non-surgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10 doi: 10.14444/3028. Article28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dengler J, Kools D, Pflugmacher R, et al. 1-year results of a randomized controlled trial of conservative management vs. minimally invasive surgical treatment for sacroiliac joint pain. Pain Physician. 2017;20:537–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duhon BS, Bitan F, Lockstadt H, et al. SIFI Study Group Triangular titanium implants for minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: 2-year follow-up from a prospective multicenter trial. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10 doi: 10.14444/3013. Article13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudolf L. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis-MIS technique with titanium implants: report of the first 50 patients and outcomes. Open Orthop J. 2012;6(1):495–502. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudolf L. MIS fusion of the SI joint: does prior lumbar spinal fusion affect patient outcomes? Open Orthop J. 2013;7:163–168. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachs D, Capobianco R. One year successful outcomes for novel sacroiliac joint arthrodesis system. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2012;6(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachs D, Capobianco R. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: one-year outcomes in 40 patients. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:536128. doi: 10.1155/2013/536128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummings J, Jr, Capobianco RA. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: one-year outcomes in 18 patients. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroeder JE, Cunningham ME, Ross T, Boachie-Adjei O. Early results of sacro–iliac joint fixation following long fusion to the sacrum in adult spine deformity. Hosp Spec Surg J. 2013;10(1):30–35. doi: 10.1007/s11420-013-9374-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AG, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. Open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a multi-center comparison of perioperative measures and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledonio CGT, Polly DW, Swiontkowski MF. Minimally invasive versus open sacroiliac joint fusion: are they similarly safe and effective? Clin Orthop. 2014;472(6):1831–1838. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3499-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledonio C, Polly D, Swiontkowski MF, Cummings J. Comparative effectiveness of open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014;2014(7):187–193. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S60370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sachs D, Kovalsky D, Redmond A, et al. Durable intermediate-to long-term outcomes after minimally invasive transiliac sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants. Med Devices (Auckl) 2016;9:213–222. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S109276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudolf L, Capobianco R. Five-year clinical and radiographic outcomes after minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular implants. Open Orthop J. 2014;8:375–383. doi: 10.2174/1874325001408010375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanaclocha V, Herrera JM, Sáiz-Sapena N, Rivera-Paz M, Verdú-López F. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, radiofrequency denervation, and conservative management for sacroiliac joint pain: 6-year comparative case series. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(1):48–55. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dengler J, Duhon B, Whang P, et al. Predictors of outcome in conservative and minimally invasive surgical management of pain originating from the sacroiliac joint: a pooled analysis. Spine. 2017 2017 Mar 27;42(21):1664–1673. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002169. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1997;26(7):477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25(22):2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. discussion 2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EuroQol Group EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bono C, Baisden J, Baker R, et al. NASS Coverage Policy Recommendations: Percutaneous Sacroiliac Joint Fusion. 2015. [Accessed July 5, 2018]. webpage on the Internet. Available from: https://www.spine.org/PolicyPractice/CoverageRecommendations/AboutCoverageRecommendations.aspx.

- 36.Lorio MP. ISASS Policy 2016 update – minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:26. doi: 10.14444/3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsey DP, Parrish R, Gundanna M, et al. Biomechanics of unilateral and bilateral sacroiliac joint stabilization: laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28(3):326–332. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.SPINE17499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Institutional review boards that approved this study

| Site ID | Site name | Approving Institutional Review Board (IRB) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Columbia Orthopedics | Washington University St. Lois |

| 5 | Medical University of South Carolina | Medical University of South Carolina |

| 7 | Gordon Spine | Western IRB |

| 16 | Resurgens Orthopaedics | Western IRB |

| 27 | Orthopedics of Oklahoma | Western IRB |

| 35 | Orthopaedic Center of Southern Illinois | Western IRB |

| 36 | Integrated Spine Care | Wheaton Franciscan IRB |

| 38 | Yale University | Yale University IRB |

| 47 | Aurora BayCare Orthopedics | Western IRB |

| 48 | Bluegrass Orthopedics | Western IRB |

| 58 | Allegheny Medical Center | Western IRB |

| 60 | Overtake Hospital | Western IRB |