Abstract

Background:

Studies assessing the prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis (MS) have used various ascertainment methods that capture different constructs. The relationships between these methods are incompletely understood. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in MS, but the effects of past diagnoses of depression and anxiety on HRQOL are largely unknown. We compared the prevalence of depression and anxiety in persons with MS using administrative data, self-reported physician diagnoses, and symptom-based measures and compared characteristics of persons classified as depressed or anxious by each method. We evaluated whether HRQOL was most affected by previous diagnoses of depression or anxiety or by current symptoms.

Methods:

We linked clinical and administrative data for 859 participants with MS. HRQOL was measured by the Health Utilities Index Mark 3. We classified participants as depressed or anxious using administrative data, self-reported physician diagnoses, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Multivariable linear regression examined whether diagnosed depression or anxiety affected HRQOL after accounting for current symptoms.

Results:

Lifetime prevalence estimates for depression were approximately 30% regardless of methods used, but 35.8% with current depressive symptoms were not captured by either administrative data or self-reported diagnoses. Prevalence estimates of anxiety ranged from 11% to 19%, but 65.6% with current anxiety were not captured by either administrative data or self-reported diagnoses. Previous diagnoses did not decrease HRQOL after accounting for current symptoms.

Conclusions:

Depression and, to a greater extent, anxiety remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in MS; both substantially contribute to reduced HRQOL in MS.

Depression and anxiety are common in multiple sclerosis (MS), and they occur more often in the MS population than in the general population.1 Depression and anxiety are associated with increased health care utilization in MS2 and other adverse outcomes.3–5 Studies assessing the prevalence of depression and anxiety in MS have used various ascertainment methods,1 including medical records review, interviews, self-reports of physician diagnoses, symptom-based questionnaires, and administrative data. Although each approach is valid in its own right, each captures different constructs and can lead to widely varying prevalence estimates for depression and anxiety.1 Medical records and administrative data capture conditions for which care was sought and a diagnosis recorded, or for which a provider recorded a diagnostic code while caring for another condition; therefore, they estimate “medically recognized prevalence.”6 Structured diagnostic interviews capture conditions for which the individual may or may not have sought care. Self-report instruments assess current symptoms of depression or anxiety and require diagnostic confirmation.7 A better understanding of the relationships between such ascertainment methods and how the populations classified as affected by these methods differ is needed to support surveillance efforts for psychiatric comorbidity in MS.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is lower in MS than in other chronic diseases.8 From the standpoint of clinical practice, psychiatric comorbidity is known to be associated with lower HRQOL in MS,9 but the effects of past diagnoses of depression and anxiety on HRQOL are largely unknown. In the general population, risk of major depression recurrence depends heavily on the number of previous episodes.10 Biological changes that occur during depressive episodes may be long-lasting and increase susceptibility to future episodes, although support for this is inconsistent.11,12

The present study had two distinct aims. First, we examined the prevalence of depression and anxiety in persons with MS using three methods: administrative data, self-reports of physician-diagnosed depression or anxiety, and symptom-based measures. We then examined the characteristics of persons classified as depressed or anxious by each method. Second, we evaluated the independent effects of previous diagnoses of depression or anxiety, in addition to current symptoms of depression and anxiety, on HRQOL, as measured by the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3).

Methods

Study Population

This analysis included 863 participants enrolled at MS clinics in British Columbia, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia.13 Clinical data for these participants were linked with their provincial administrative data. In each province, we obtained ethics approval, participant consent, and approval to access administrative data.

Clinical Data Set

At study enrollment we used standardized methods to abstract demographic and clinical information from medical records, including sex, date of birth, race, age at MS symptom onset, clinical course,14 and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score.15 Participants also completed the HUI3; the Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use (D-FIS); the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a validated comorbidity questionnaire16; and validated questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey regarding smoking history.17 The HUI is a generic 15-item health utility measure, validated in the MS population,18 that assesses patient-reported health states with respect to vision, hearing, speech, mobility, dexterity, cognition, pain, and emotion. This assessment provides a multi-attribute interval utility measure with linear metrics with values ranging from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). It allows for negative values considered worse than death.19 As reviewed recently,20 the HUI demonstrates convergent validity with measures of impairment (pooled r = 0.73); can discriminate among mild, moderate, and severe disability in MS; does not have floor or ceiling effects; and has good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.87). The D-FIS assesses fatigue using eight items that are scored from 0 (no) to 4 (extreme problem) and summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 32.21 The D-FIS shows convergent validity with other fatigue measures, minimal floor and ceiling effects (both 1.54%), good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach α = 0.91), and good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.81).22 The HADS is a 14-item questionnaire assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression in medically ill populations.23 In the MS population, a score of 8 or greater on the depression subscale (HADS-D) is sensitive (90.0%) and specific (87.3%) for major depression as identified by a structured interview.7 A score of 11 or greater has lower sensitivity (60.0%) but higher specificity (96.7%). A score of 8 or greater on the anxiety subscale (HADS-A) is sensitive (73.2%) and specific (84.8%) for generalized anxiety disorder. A score of 11 or greater has much lower sensitivity (43.9%) but higher specificity (96.0%). The validated comorbidity questionnaire asked “Has a doctor ever told you that you have…?” for 21 conditions, including physical comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, glaucoma, cataracts, migraine, autoimmune thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, and osteoporosis) and psychiatric comorbidities (depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia).16 For each affirmative response, the participant was asked whether the condition was currently being treated and the year of diagnosis.

Administrative Data

Provincial health insurance programs provide public funds to care for nearly all residents within each province. Computerized records of all hospitalizations and physician visits24–26 include a unique personal health care identification number facilitating linkage across data sets. Population (insurance) registries capture sex and dates of birth, death, and insurance coverage for each beneficiary. Hospital discharge abstracts include diagnostic codes reported as five-digit International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision, or 10th Revision, Canada, codes. Physician claims include service date and a three-digit ICD-9 code for one physician-assigned diagnosis.

Defining Depression and Anxiety

We classified participants as depressed or anxious in three ways. First, we applied validated case definitions for depression and anxiety27,28 to the administrative data (Table S1 (231.6KB, pdf) , published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org); once a participant met the case definition, he or she was considered affected thereafter. For this analysis, administrative data began in 1990–1991 or 1991–1992 depending on the province and ended at study enrollment. Thus, administrative case definitions provided a cumulative “lifetime” prevalence of depression and anxiety among individuals who sought care from physicians; contacts with nonphysician mental health providers, such as counselors, are not captured. Second, we used participant reports of physician-diagnosed depression and anxiety (lifetime), hereinafter referred to as “physician diagnosed.” Third, we used the HADS, with a score of 8 or greater on the depression subscale indicating current probable major depression and a score of 8 or greater on the anxiety subscale indicating current probable generalized anxiety. These three ways accounted for the approaches used in 79.7% of studies evaluating the incidence or prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a recent systematic review1; medical records review was considered in only 3.4% of those studies. Structured diagnostic interviews were not included in the study protocol due to feasibility limitations related to the need for trained interviewers and the associated costs.

Statistical Analysis

Because privacy regulations prevent individual-level administrative data from leaving the province of origin, analyses of linked data were performed in parallel at each site, and the findings were aggregated; cell sizes less than five were suppressed. For both objectives, we summarized continuous variables using mean (SD) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. We conducted univariate analyses of the associations between pairs of variables using χ2 tests, t tests, and Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate.

To address the first study objective, we used linked data to determine the lifetime prevalence of depression and anxiety based on the administrative case definitions and physician diagnoses. We compared agreement between these data sources using a kappa (κ) statistic, interpreted as slight (0–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), and almost perfect (0.81–1.0) agreement.29 Second, we determined the prevalence of current depression and anxiety based on the HADS score. Third, we evaluated the overlap of all the classification methods simultaneously and summarized the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, including smoking status, classified according to each approach. Because these groups were not mutually exclusive (ie, were overlapping), we were unable to perform formal statistical tests of these comparisons.

To address the second study objective, we used the clinical data set only and evaluated whether reports of physician-diagnosed depression or anxiety affected HRQOL after accounting for current symptoms of depression and anxiety based on the HADS score. This evaluation allowed for combined analyses of data from all the sites instead of being limited to within-province analyses. We classified depression status as follows: 1) depression-inactive if the participant reported physician-diagnosed depression but a HADS-D score less than 8; 2) depression-active if the participant reported physician-diagnosed depression and a HADS-D score of 8 or greater; 3) depression-undiagnosed if the participant had a HADS-D score of 8 or greater but did not report physician-diagnosed depression; and 4) no depression if the participant had a HADS-D score less than 8 and did not report physician-diagnosed depression. Anxiety status was classified similarly. Using multivariable linear regression, we evaluated the association of depression and anxiety status with the HUI3 score, using no depression or no anxiety as the reference group as appropriate. Covariates included disability (EDSS score, as continuous variable),18 age (continuous, in years), sex, education as a measure of socioeconomic status (categorized as high school or less [reference group] and more than high school), and number of physical comorbidities (continuous) given the associations of these factors with HRQOL.30 Although use of the number (count) of physical comorbidities rather than individual comorbidities has the limitation that it assumes that all comorbidities have the same effect on HRQOL, counts are strongly associated with several health care outcomes31 and were considered most appropriate herein because of the large number of comorbidities queried and the low frequencies of several of them. The listed covariates were included in all the multivariable models as a single block. Disease duration (continuous) and course (relapsing vs. progressive at onset) were considered as covariates but were dropped from regression models because they were not associated with the outcome, and neither were they confounders of the associations of interest. Because fatigue directly affects HRQOL and mediates the effects of depression and anxiety on HRQOL, we created models with and without this covariate as measured by the D-FIS (continuous).

Sensitivity Analyses

Using linked clinical-administrative data, we substituted lifetime diagnoses of depression or anxiety based on administrative data for those based on patient reports of physician diagnoses in the regression models. In another sensitivity analysis, we used a HADS score of 11 or greater rather than a score of 8 or greater to classify an individual as depressed or anxious in the regression models. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Characteristics

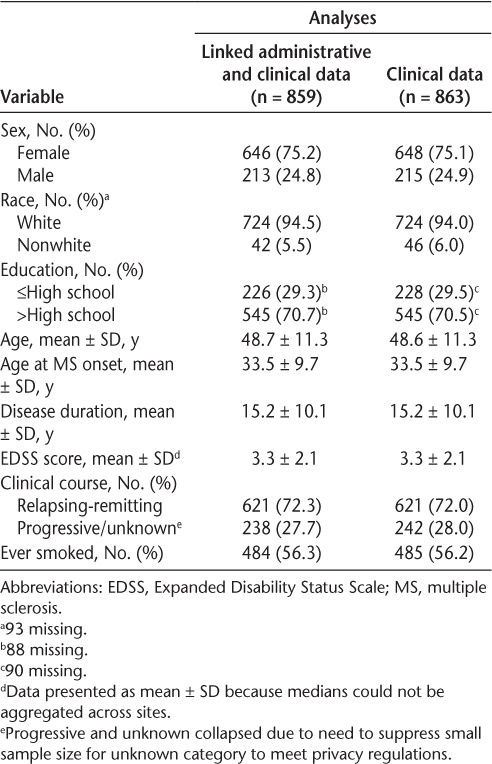

Of 863 participants, clinical data for 859 (99.5%) were linked to administrative data. Most participants were female, with a mean (SD) age of 48.7 (11.3) years (Table 1).13

Table 1.

Characteristics of study populations

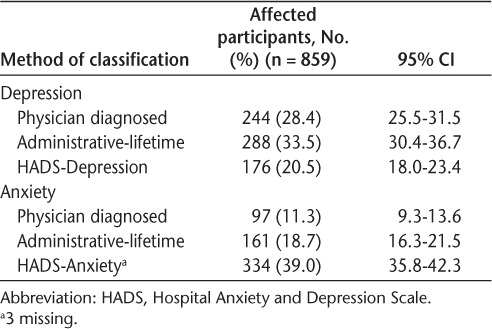

Depression

The prevalence of depression differed according to the ascertainment method, and only 66 (7.7%) were identified by all three methods (Table 2 and Figure S1 (231.6KB, pdf) ). Lifetime prevalence was higher using the administrative definition than using reports of physician-diagnosed depression. Agreement between the administrative definition and physician-diagnosed depression was moderate (κ = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42–0.54). The proportion of participants reporting significant depressive symptoms currently was 20.5%; this was lower than either lifetime estimate.

Table 2.

Number of participants classified as depressed or anxious using different approaches

Of the 176 participants with a HADS-D score of 8 or greater, 94 (53.4%) reported physician-diagnosed depression and 85 (48.3%) met the administrative definition for lifetime depression, but 63 (35.8%) were not captured by either method, suggesting that one-third were undiagnosed (Figure S1 (231.6KB, pdf) ). Of the 244 participants with physician-diagnosed depression, 94 (38.5%) currently had a HADS-D score of 8 or greater and 170 (69.7%) met the administrative definition. Of those meeting the administrative definition of depression, 85 of 287 (29.6%) had a HADS-D score of 8 or greater and 170 of 288 (59.0%) reported physician-diagnosed depression.

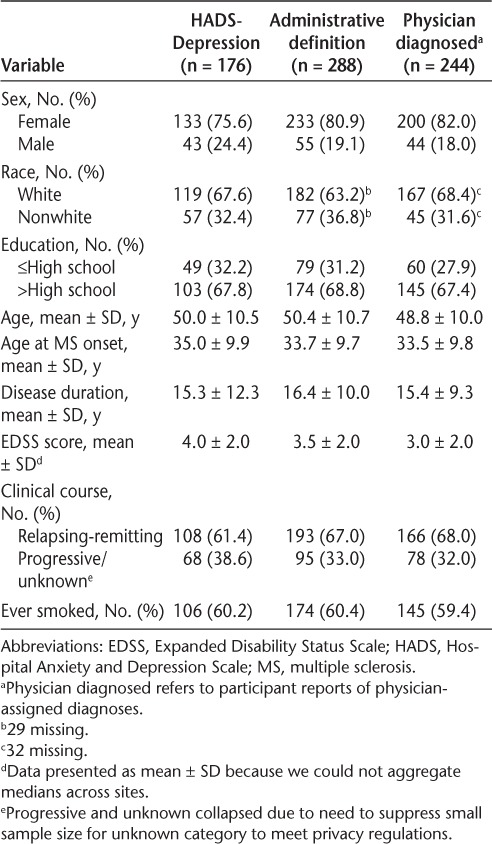

Of the participants with a HADS-D score of 8 or greater who reported physician-diagnosed depression, 83.8% reported ongoing treatment, similar to the frequency of those with physician-diagnosed depression whose HADS-D score was less than 8 (78.5%, P = .28). The characteristics of the participants classified as depressed were similar, regardless of the method used (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of depressed participants according to method of identifying depression

Anxiety

Just 35 (4.1%) of the 859 linked participants were identified as having anxiety by all three methods (Figure S2 (231.6KB, pdf) ). Similar to depression, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety was higher using the administrative definition than using reports of physician-diagnosed anxiety. However, the proportion of participants with clinically significant current anxiety symptoms was higher than either lifetime prevalence estimate and higher than the proportion of participants with depressive symptoms.

Of the 334 participants with a HADS-A score of 8 or greater, 77 (23.1%) reported physician-diagnosed anxiety and 73 (21.9%) met the administrative definition for lifetime anxiety, but 219 (65.6%) were not captured by either method, suggesting that two-thirds had undiagnosed anxiety (Figure S2 (231.6KB, pdf) ). Of the 97 participants with physician-diagnosed anxiety, 77 (79.4%) currently had a HADS-A score of 8 or greater, and 50 (51.5%) met the administrative definition of anxiety. Agreement between the administrative definition and physician-diagnosed anxiety was only fair (κ = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.17–0.33). Of the 161 participants meeting the administrative definition of anxiety, 42 (26.1%) had a HADS-A score of 8 or greater and 50 (31.1%) reported physician-diagnosed anxiety.

Of those with a HADS-A score of 8 or greater who reported physician-diagnosed anxiety, 73.2% reported ongoing treatment, lower than the frequency of those with physician-diagnosed anxiety whose HADS-A score was less than 8 (87.0%, P = .17).

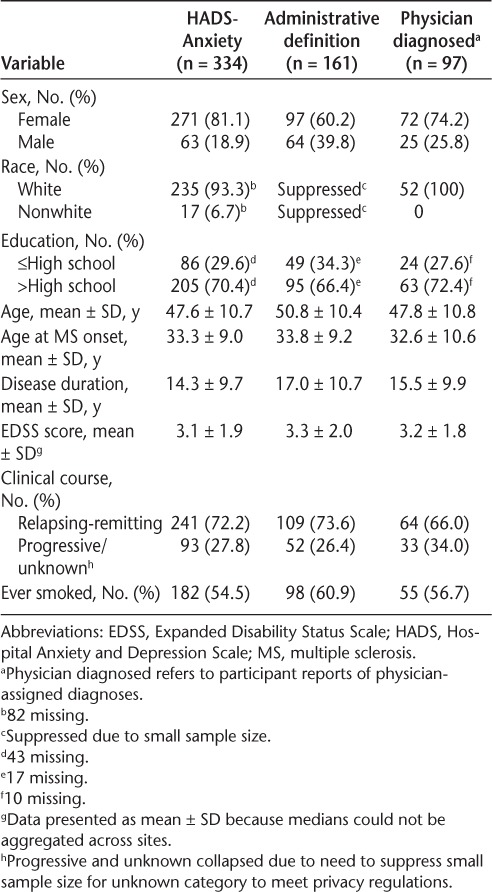

We observed some differences in the participants classified with anxiety depending on the method used (Table 4). Relatively more women were classified with anxiety using the HADS-A or physician diagnosis than using administrative data. Disease duration was longer in those identified using administrative data than by the other methods.

Table 4.

Characteristics of anxious participants according to method of identifying anxiety

Quality of Life

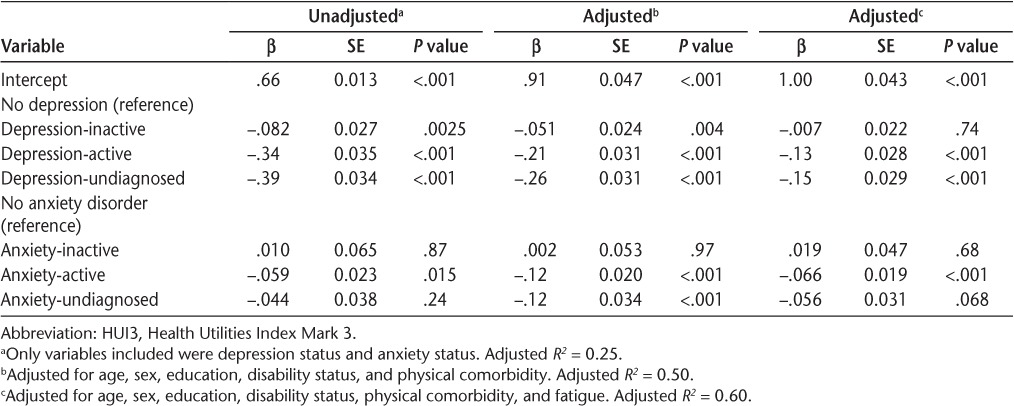

Overall, the mean (SD) HUI3 score was 0.54 (0.32).13 Within groups, mean HUI3 scores were highest for those who were not depressed and lowest for those with undiagnosed depression (Figure S3A (231.6KB, pdf) ). Findings were similar for anxiety status (Figure S3B (231.6KB, pdf) ). In the linear regression model that included depression and anxiety status simultaneously, all categories of depression were associated with reduced HRQOL compared with no depression (Table 5). The effect of undiagnosed depression was slightly greater than that of active, diagnosed depression. All categories of anxiety were associated with reduced HRQOL compared with no anxiety, although only the effect of active anxiety was statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between depression and anxiety status and health-related quality of life as measured by HUI3

On multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, education, disability status, and physical comorbidity, all categories of depression were associated with reduced HRQOL, but inactive depression had a small effect (Table 5) (model-adjusted R2 = 0.50). Inactive anxiety was not associated with reduced HRQOL. Undiagnosed anxiety reduced HRQOL to the same degree as active, diagnosed anxiety. With additional adjustment for fatigue, inactive depression was no longer associated with reduced HRQOL. Although the effects of active depression and undiagnosed depression were reduced compared with the previous model, the magnitude of the effects exerted by each condition remained similar to each other. Findings for anxiety were essentially unchanged.

In the sensitivity analysis in which we substituted lifetime diagnoses of depression or anxiety based on administrative data for those based on reports of physician-based diagnoses in the regression models, the findings were unchanged (data not shown). When we used a stricter cut-point for the HADS (score ≥11), fewer participants were classified as depressed (16.6%) or anxious (7.4%), as expected. Although the effect estimates changed slightly, regression models that incorporated these cut-points in the classification of depression or anxiety status produced the same conclusions (Table S2 (231.6KB, pdf) ).

Discussion

The estimated lifetime prevalence of depression was approximately 30%, regardless of whether we used administrative data or patient reports of physician diagnoses as the ascertainment method, whereas we found a prevalence of 21% when using a screening tool for current symptoms of depression. In contrast, the lifetime prevalence estimates of anxiety ranged from 11% to 19%, but the prevalence was higher (39%) when the screening tool for current symptoms was used and exceeded that for depression.

Depression and anxiety are associated with increased morbidity in MS,4,9 yet we found that these conditions were frequently undiagnosed; one-third of individuals with significant current symptoms of depression and two-thirds with significant current symptoms of anxiety had not been diagnosed as having these conditions. After adjustment for potential confounders, active depression and undiagnosed depression reduced HRQOL to a similar degree, whereas inactive depression had no effect. This same pattern emerged for anxiety. Thus, current mental health symptoms had a greater effect on current HRQOL than did a history of diagnosed depression or anxiety, highlighting the importance of screening for mental health conditions in routine clinical care for MS.

Up to one-third of the participants seemed to have undiagnosed depression based on their report of elevated symptoms in the absence of lifetime previous diagnoses. Other researchers have also identified underdiagnosed depression in MS. An Irish study found that only one-third of those with moderate-severe depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory–II had diagnoses of depression.32 Of 8983 participants in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis Registry, one-third with scores indicating probable major depression on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale did not report a diagnosis of depression.33 Notably, although we found that most participants with past diagnoses of depression were treated, many still reported significant current symptoms, suggesting inadequate treatment. Another recent Canadian study found that 85% of persons with MS and depression were treated for depression,34 more than in previous reports,32 but that many remained symptomatic regardless. Thus, undertreatment, as well as lack of treatment, likely contributes to the reported chronicity of depression in MS.35 Similarly, two-thirds of participants with elevated HADS-A scores did not have lifetime diagnoses of anxiety, suggesting undiagnosed anxiety. This is also consistent with a previous Canadian study that found a 35% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorder based on a structured clinical interview, of whom only one-third had a formal diagnosis.36 Although adequacy of treatment in those diagnosed as having anxiety remains largely unexplored, the present findings suggest that this is also a major concern.

The present findings also underscore the adverse effects of undiagnosed depression and anxiety on HRQOL. The HUI3 score changes of 0.02 to 0.04 are considered clinically meaningful,37 and in the adjusted model that accounted for fatigue, active depression and undiagnosed depression were associated with substantial reductions in HRQOL. Although the effects of active and undiagnosed anxiety were more modest, they were clinically meaningful nonetheless and are particularly relevant at the population level given the high prevalence of anxiety and the fact that the average reported HUI3 score for the present sample was already below that considered to reflect severe disability in HRQOL.38 Most previous studies examining the effects of depression and anxiety on HRQOL in MS have relied on symptom-based measures alone39 rather than also considering current or remote formal diagnoses. One previous Canadian study found that lifetime history of depression was associated with reduced HRQOL but did not evaluate whether this was independent of current symptoms.40 The present findings suggest that if current symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue are captured, knowledge of previous diagnoses of depression and anxiety adds little explanatory information regarding current HRQOL. This highlights the fact that clinicians cannot rely on their knowledge of the presence or absence of a previous diagnosis of these conditions, and neither should they presume that a diagnosed condition is adequately managed. Rather, efforts aimed at improving HRQOL should focus on current symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Agreement between reports of physician-diagnosed depression and the administrative definition of depression was moderate, and agreement between reports of physician-diagnosed anxiety and the administrative definition of anxiety was fair. These findings are consistent with previous evaluations of administrative case definitions for depression and anxiety in MS samples in Manitoba and Nova Scotia27,28 (ie, κ for depression = 0.49, κ for anxiety = 0.26) and with an earlier study in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan that examined agreement between an administrative definition of depression and medical records (κ = 0.54).41 The challenges of developing administrative definitions for depression and anxiety are well recognized,42 and we are unaware of other work validating administrative definitions for anxiety at the individual level. Lack of specificity of the three-digit ICD-9 codes used in physician billing can make it difficult to distinguish depression and anxiety, and the sensitivity of administrative data is limited because mental health care obtained through psychologists and other nonphysician providers is not captured. It is also possible that participants may not recall physician diagnoses of depression or anxiety, particularly long after diagnosis. Nonetheless, regardless of the method of identifying depression or anxiety, the characteristics of the affected MS populations were largely similar.

The strengths of this study include the large sample and consideration of multiple factors that influence HRQOL, but limitations must be recognized. Administrative data are not collected for research purposes, although we used definitions for depression and anxiety previously validated in two of the three provinces under study and saw that performance of these definitions was consistent in the present sample. We recruited participants through MS clinics, potentially limiting generalizability,43 although two of the clinics are the sole specialized MS care centers in their respective provinces. The HADS is a screening tool and, as such, requires a clinical interview to confirm diagnoses of depression or anxiety disorder. Nonetheless, it is sensitive and specific in the MS population.7

The present findings suggest that emphasis should be placed on current symptoms rather than on recorded history of mental health issues. Current symptoms are the link between diagnostic categories and lowered HRQOL, supporting the idea that these should be the focus of detection and monitoring efforts. Future research should explore how best to incorporate symptom ratings into broader clinical strategies to improve HRQOL.

PRACTICE POINTS

Depression and anxiety are underdiagnosed and undertreated in MS.

Previous diagnoses of depression and anxiety do not affect health-related quality of life (HRQOL) after accounting for current symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Self-reports of physician-diagnosed depression or anxiety have a similar association with HRQOL as depression and anxiety identified using administrative (health claims) data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Team in the Epidemiology and Impact of Comorbidity on Multiple Sclerosis investigators (ECoMS; by site): University of Manitoba (James Blanchard, MD, PhD; Patricia Caetano, PhD; Lawrence Elliott, MD, MSc; Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD; Bo Nancy Yu, MD, PhD); Dalhousie University (Virender Bhan, MBBS; John D. Fisk, PhD), University of Alberta (Joanne Profetto-McGrath, PhD; Sharon Warren, PhD; Larry Svenson, BSc); McGill University (Christina Wolfson, PhD); University of British Columbia (Helen Tremlett, PhD); and University of Calgary (Nathalie Jette, MD, MSc; Scott Patten, MD, PhD). Analysts (by site): University of Manitoba (Stella Leung); McGill University (Bin Zhu); and Dalhousie University (Yan Wang). Contributors (by site): Nicholas Hall, BSc (University of Manitoba, study coordinator); Feng Zhu, PhD (University of British Columbia, analytic support); Elaine Kingwell, PhD (University of British Columbia, study coordination support), and Karen Stadnyk, MSc (Dalhousie University, study coordinator).

Financial Disclosures:

Dr. Marrie receives research funding from the CIHR, Research Manitoba, MS Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Research Foundation (MSSRF), National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), Rx & D Health Research Foundation, Crohn's and Colitis Canada, and the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis and has conducted clinical trials funded by Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Patten was a member of an advisory board for Servier, Canada; has received honoraria for reviewing investigator-initiated grant applications submitted to Lundbeck and Pfizer; and has received speaking honoraria from Teva and Lundbeck. He is the editor in chief of the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry and a member of the editorial board of Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada. He is the recipient of a salary support award (Senior Health Scholar) from Alberta Innovates, Health Solutions, and receives research funding from CIHR, the Institute of Health Economics, and the Alberta Collaborative Research Grants Initiative. Dr. Berrigan receives research funding from the CIHR and Canada Foundation for Innovation. Dr. Tremlett holds the Canada Research Chair for Neuroepidemiology and Multiple Sclerosis and currently receives research support from the NMSS, the CIHR, the MS Society of Canada, and the MSSRF. In the past 5 years she has received research support from the MS Society of Canada (Don Paty Career Development Award), the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Scholar Award), and the UK MS Trust; speaker honoraria and/or travel expenses to attend conferences from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (2013), the NMSS (2012, 2014, 2016), Teva Pharmaceuticals (2011), European Committee on Treatment and Research in MS (2011–2016), UK MS Trust (2011), the Chesapeake Health Education Program, US Veterans Affairs (2012), Novartis Canada (2012), Biogen Idec (2014), and American Academy of Neurology (2013–2016). All speaker honoraria are either declined or donated to an MS charity or to an unrestricted grant for use by her research group. Dr. Wolfson receives research funding from the MS Society of Canada, CIHR, Canada Foundation for Innovation, and NMSS. She has received a speaking honorarium from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Warren receives research funding from the CIHR. Ms. McKay holds a doctoral award from the CIHR. Dr. Fisk receives research funding from the CIHR, MS Society of Canada, NMSS, and Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation. Ms. Leung and Dr. Fiest have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support:

This study was supported (in part) by the CIHR (CIBG 101829), the Rx & D Health Research Foundation, a Don Paty Career Development award from the MS Society of Canada (to Dr. Marrie), a Manitoba Research Chair from Research Manitoba (to Dr. Marrie), the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis (to Dr. Marrie), a postdoctoral fellowship from the MS Society of Canada (to Dr. Berrigan), and a doctoral award from CIHR (to Ms. McKay).

Disclaimer:

The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the data stewards. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health, Population Data BC, or Pharmanet is intended or should be inferred. Some data used in this report were made available by Health Data Nova Scotia of Dalhousie University. Although some of this research is based on data obtained from the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, the observations and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent those of either Health Data Nova Scotia or the Department of Health and Wellness.

References

- 1. Marrie R, Reider N, Cohen J, . et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015; 21: 305– 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marrie RA, Elliott L, Marriott J, Cossoy M, Tennakoon A, Yu N.. Comorbidity increases the risk of hospitalizations in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015; 84: 350– 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, Gatto N, Baumann KA, Rudick RA.. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1997; 54: 531– 533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marrie RA, Elliott L, Marriott J, . et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015; 85: 240– 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang T, Tremlett H, Leung S, . et al. Examining the effects of comorbidities on disease-modifying therapy use in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2016; 86: 1287– 1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watson DE, Heppner P, Roos NP, Reid RJ, Katz A.. Population-based use of mental health services and patterns of delivery among family physicians, 1992 to 2001. Can J Psychiatry. 2005; 50: 398– 406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Honarmand K, Feinstein A.. Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 1518– 1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hermann B, Vickrey B, Hays RD, . et al. A comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with epilepsy, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Epilepsy Res. 1996; 25: 113– 118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amato MP, Ponziani G, Rossi F, Liedl CL, Stefanile C, Rossi L.. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue and disability. Mult Scler. 2001; 7: 340– 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bulloch A, Williams J, Lavorato D, Patten S.. Recurrence of major depressive episodes is strongly dependent on the number of previous episodes. Depress Anxiety. 2014; 31: 72– 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR.. Are people changed by the experience of having an episode of depression? a further test of the scar hypothesis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990; 99: 264– 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zeiss AM, Lewinsohn PM.. Enduring deficits after remissions of depression: a test of the scar hypothesis. Behav Res Ther. 1988; 26: 151– 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berrigan LI, Fisk JD, Patten SB, . et al. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects of comorbidity. Neurology. 2016; 86: 1417– 1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lublin FD, Reingold SC.. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. Neurology. 1996; 46: 907– 911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983; 33: 1444– 1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horton M, Rudick RA, Hara-Cleaver C, Marrie RA.. Validation of a self-report comorbidity questionnaire for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2010; 35: 83– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisk JD, Brown MG, Sketris IS, Metz LM, Murray TJ, Stadnyk KJ.. A comparison of health utility measures for the evaluation of multiple sclerosis treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005; 76: 58– 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G.. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003; 1: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuspinar A, Mayo NE.. A review of the psychometric properties of generic utility measures in multiple sclerosis. PharmacoEconomics. 2014; 32: 759– 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fisk JD, Doble SE.. Construction and validation of a fatigue impact scale for daily administration (D-FIS). Qual Life Res. 2002; 11: 263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benito-Leon J, Martinez-Martin P, Frades B, . et al. Impact of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: the Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use (D-FIS). Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 645– 651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP.. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67: 361– 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. . Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations): 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/internal/health/dad. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- 25. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. . Medical Services Plan (MSP): 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/internal/health/msp. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- 26. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. . Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing): 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/internal/population/consolidationfile. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- 27. Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Yu BN, . et al. Mental comorbidity and multiple sclerosis: validating administrative data to support population-based surveillance. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Stadnyk KJ, . et al. Performance of administrative case definitions for comorbidity in multiple sclerosis in Manitoba and Nova Scotia. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014; 34: 145– 153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Landis JR, Koch GG.. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33: 159– 174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T.. Cumulative impact of comorbidity on quality of life in MS. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012; 125: 180– 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM.. How to measure comorbidity: a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003; 56: 221– 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGuigan C, Hutchinson M.. Unrecognised symptoms of depression in a community-based population with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006; 253: 219– 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marrie RA, Horwitz RI, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T.. The burden of mental comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: frequent, underdiagnosed, and under-treated. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 385– 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raissi A, Bulloch AG, Fiest KM, McDonald K, Jette N, Patten SB.. Exploration of undertreatment and patterns of treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 292– 300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koch MW, Patten S, Berzins S, . et al. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a long-term longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2015; 21: 76– 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Korostil M, Feinstein A.. Anxiety disorders and their clinical correlates in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 67– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Samsa G, Edelman D, Rothman ML, Williams GR, Lipscomb J, Matchar D.. Determining clinically important differences in health status measures: a general approach with illustration to the Health Utilities Index Mark II. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999; 15: 141– 155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feng Y, Bernier J, McIntosh C, Orpana H.. Validation of disability categories derived from Health Utilities Index Mark 3 scores. Health Reports. 2009; 20: 43– 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González J-MM, Rivera-Navarro J.. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4: 556– 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang JL, Reimer MA, Metz LM, Patten SB.. Major depression and quality of life in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2000; 30: 309– 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. West SL, Richter A, Melfi CA, McNutt M, Nennstiel ME, Mauskopf JA.. Assessing the Saskatchewan database for outcomes research studies of depression and its treatment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000; 53: 823– 831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kisely S, Lin E, Lesage A, . et al. Use of administrative data for the surveillance of mental disorders in 5 provinces. Can J Psychiatry. 2009; 54: 571– 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McKay KA, Tremlett H, Zhu F, Kastrukoff L, Marrie RA, Kingwell E.. A population-based study comparing multiple sclerosis clinic users and non-users in British Columbia, Canada. Eur J Neurol. 2016; 23: 1093– 1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.