Abstract

Background:

Mood disorders are highly prevalent in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). MS causes changes to a person's sense of self. The Social Identity Model of Identity Change posits that group membership can have a positive effect on mood during identity change. The family is a social group implicated in adjustment to MS. The objectives of this study were to investigate whether family identity can predict mood in people with MS and to test whether this prediction was mediated by social support and connectedness to others.

Methods:

This cross-sectional survey of 195 participants comprised measures of family identity, family social support, connectedness to others, and mood.

Results:

Family identity predicted mood both directly and indirectly through parallel mediators of family social support and connectedness to others.

Conclusions:

Family identity predicted mood as posited by the Social Identity Model of Identity Change. Involving the family in adjustment to MS could reduce low mood.

The prevalence of mood disorders in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) is high,1–3 with people with MS having higher rates of depression1,2 and anxiety3,4 than people with other neurologic conditions or the general population. Mood disorders, both anxiety and depression, have a large negative effect on the lives of people with MS, and both are negatively correlated to quality of life.5 Therefore, considering both anxiety and depression together as an overall indicator of mood could provide greater insight into the negative effects of MS. One explanation for the high prevalence of mood disorders is that the symptoms of MS can cause changes to the way that a person views himself or herself.6 These changes can alter a person's social identity, resulting in a negative effect on a person's psychological well-being and mood.7

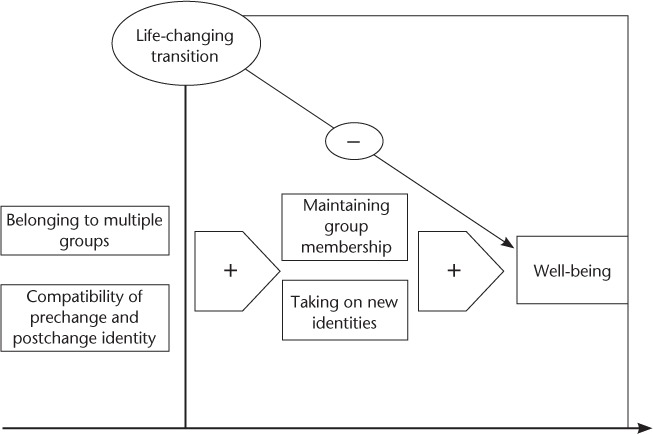

However, not everyone who receives a diagnosis of MS experiences the same effects to mood.8 One explanation for the different responses to the diagnosis of MS can be explained by the Social Identity Model of Identity Change (SIMIC) (Figure 1).9 The model suggests that maintaining group membership and taking on new identities after a life-changing transition can protect against the negative effects of identity change. Maintaining social group identity after a life-changing transition can aid in the establishment of and adjustment to a new sense of self by providing social support and connectedness to others.

Figure 1.

A diagrammatic representation of the Social Identity Model of Identity Change7,9

Reproduced with permission from Jetten J, Haslam AS, Haslam C. The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-being. Hove, UK, and New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012 (Figure 6.1).

In accordance with the SIMIC, maintaining group membership with a preestablished social group, such as the family, could have positive implications for adjustment to MS. The family can aid in identity reconstruction after identity change in response to an MS diagnosis.10 Identifying with the family group after a diagnosis of MS could provide a source of social support and connectedness to others in line with the SIMIC,9 providing positive effects to a person's mood.

The SIMIC posits that social support provided by previously established groups can help with the adjustment process. Social support can be defined as “the provision or exchange of emotional, informational or instrumental resources in response to others needs.”11(p780) In addition, social support has been found to facilitate adjustment to MS.12,13 Family support has been found to be a salient factor in an individual's adjustment to MS,12 and it is often cited as being the main source of emotional and physical support for people with MS.14

A diagnosis of MS can cause a change in social identities that can have an effect on mood. Taking on new identities after an identity transition, such as being diagnosed as having MS, could have positive effects on mood.7 Maintaining group membership may lead to connectedness to others and could contribute to the positive effects on mood.

An investigation into the effects of social identity on mood would allow us to test the SIMIC in an MS population. There were two objectives to this study: first, to investigate whether family identity can predict mood in people with MS and, second, to test whether this prediction was mediated by social support and connectedness to others, in line with the SIMIC.9

Methods

Study Design and Approvals

The design of the research was a cross-sectional survey. Questionnaires were used to collect data. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the London-Bromley National Research Ethics Service committee (14/LO/0703) and research and development approval was granted by University Hospitals of Leicester National Health Service (NHS) Trust.

Sampling

Participants were identified from two sources: people with MS who had attended the Neurology Service at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust and people who were recruited via the MS Society's research webpage. An a priori power calculation based on three potential predictor variables and a medium effect size of 0.15 (α = .05) indicated that a total of 119 participants would be required to provide 0.95 power. However, due to the low expected response rate with survey methods, the questionnaire was sent to 400 participants. An alphabetical list of past and current patients with MS older than 18 years was compiled from the patient database at University Hospitals of Leicester Neurology Service. Those in the database had visited the clinic in the 6 months before the list was compiled in August 2014. Every fourth name on the list was compiled to form a quasi-randomized sample of 400 potential participants, who were sent invitations to take part and questionnaire packs. The packs contained a participant information sheet that outlined the purpose of the study, why the participant had been chosen to take part, what the study would entail, any risks to taking part, who had provided ethical approval for the study, and contact details for further information.

The other source of participants was through the MS Society website. An online version of the questionnaire pack was hosted on the research section of the MS Society website between August 2014 and March 2015. The information on the website consisted of the same information sent to participants in the questionnaire packs.

Procedure

Invitations to take part and questionnaire packs were compiled. We explained to participants in the invitations, and preceding the online questionnaire, that completing and returning the questionnaire packs would imply consent. Participants were asked to complete demographic information and the following questionnaires: Social Identification Scale,15 Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support,16 Exeter Identity Transition Scales–new groups subscale,7 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).17 To our knowledge, the first three of these scales, including the Exeter Identity Transition Scales generally, have not been used in MS samples previously; therefore, a reliability analysis was conducted to record the internal consistency of the scales used in this study.

Social Identification Scale

This scale is a four-item measure of a person's identification with a social group. The scale was designed so that questions can be adapted to focus on the social group under investigation by substituting the section in brackets with the social group under investigation; for example, I identify with [social group]. The scale was adapted in this study to focus on the family group. Participants were asked to rate items such as, “I see myself as a member of the family group” on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 = do not agree at all to 7 = agree completely. Family identity was scored as the sum of all four items, with higher scores indicating greater family identity.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

This scale is a 12-item measure of three aspects of a person's perceived social support: family, friends, and significant other, with four questions covering each aspect. Participants rated items on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree. All 12 items were summed to provide an overall score of perceived social support. The scores on the family and significant other subscales were combined to provide an overall score for the family group. Higher scores suggest greater perceived social support.

Exeter Identity Transition Scales–New Groups Subscale

The new groups subscale of the Exeter scales is a four-item measure and was used to investigate new groups that participants had engaged with after their diagnosis of MS, whether they have any friends in these groups, and whether they identify with these groups. Participants rate items on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = do not agree at all to 7 = agree. Higher scores suggest greater engagement with new groups after a diagnosis of MS.

The HADS

The HADS is a 14-item scale of two aspects of mood (depression and anxiety), with seven items each. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3), with some items reverse scored. The total scores of the anxiety and depression subscales were combined to provide an overall measure of mood. Cutoff values indicate normal, borderline, and abnormal cases. The scale has been validated and has a high level of internal reliability in a sample of people with MS, with Cronbach's α values of 0.83, 0.77, and 0.87 for anxiety, depression, and total score, respectively.18

Inclusion Criteria

Participants were invited to participate if they had a diagnosis of MS (including benign, relapsing-remitting, secondary progressive, and primary progressive type) and were 18 years or older. Participants attending the MS Clinic at Leicester General Hospital had a confirmed diagnosis of MS, and questionnaires were sent only to those older than 18 years. For the online version of the questionnaire, there was a clear statement before the first question saying that we were interested in people with MS older than 18 years. Due to this sampling technique, there was no way to check this.

Analysis

The data provided by participants were entered into and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). A nonnormal distribution of scores was found on all predictor questionnaires: family identity new groups, family social support, and new groups (Shapiro-Wilk ≤ 0.05 for all). A normal distribution of scores was found on the dependent variable, HADS total score (Shapiro-Wilk ≥ 0.05). Because of this result, a bootstrapping mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS add-on for IBM SPSS.19 Mediation analysis is a technique used to test how a causal variable has an effect on a dependent variable, using ordinary least squares regression analysis.19 By conducting a regression analysis on the independent variables associated with the dependent variables, the standardized regression coefficients were examined to see whether the effect of family identity on mood scores was greater than its indirect effects on social support or willingness to join new social groups. Descriptive statistics were examined, and a mediation analysis was conducted.

A parallel mediator model was used to test whether family identity had a positive effect on mood through these mediators. This model assumes that two unrelated variables mediate the relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable; in this case, family social support and willingness to engage in new groups both mediate the relationship between family identity and mood. By conducting a regression analysis on the independent variables associated with the dependent variables, the standardized regression coefficients were examined to see whether the effect of family identity on mood scores was greater than its indirect effects on social support or willingness to join new social groups.

Results

Participants

In total, 123 of 400 individuals invited returned the postal copy of the questionnaire (response rate, 30.75%). A further 80 participants completed an online version of the questionnaire through the MS Society website, providing a sample of 203 participants.

Data Preparation

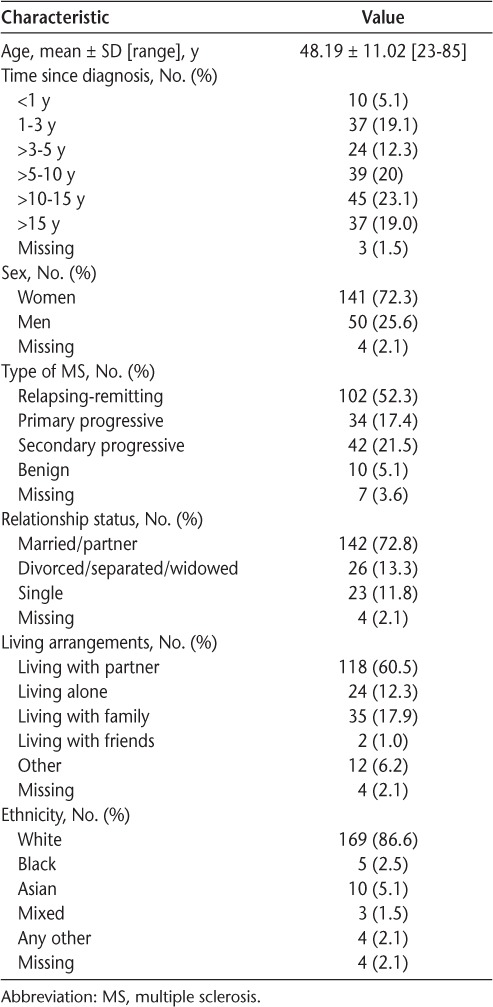

Some participants did not complete all the questions before submitting the questionnaire. Because the questionnaire was completely anonymized, participants could not be contacted to provide the missing information. We decided that for participants missing a single question from any scale, mean substitution based on the participant's scores on every other item on the questionnaire was used to enter the missing data. Participants who had missed more than one question on a questionnaire were excluded from the analysis. Eight participants were removed from the analysis due to missing data, bringing the total sample to 195. The demographic characteristics of the final sample used are shown in Table 1. The means, SDs, and correlations of the variables included in the analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the 195 participants in final sample

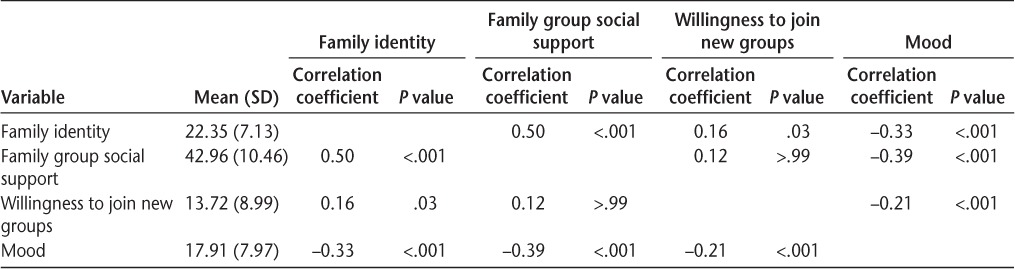

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables included in mediation analysis

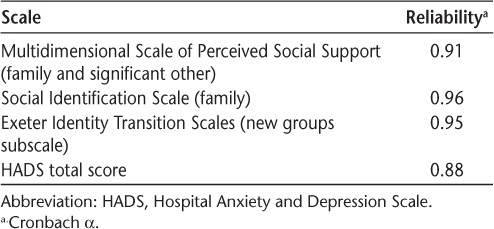

Results of the reliability analysis are shown in Table 3. All the scales used in the study had high internal consistency.

Table 3.

Internal consistency of scales used

Family identity was found to be significantly positively correlated with family group social support (P < .01) and willingness to join new groups (P < .05) and negatively correlated with mood (P < .01). Family group social support and willingness to join new groups were found to be negatively correlated with mood (P < .01 for both).

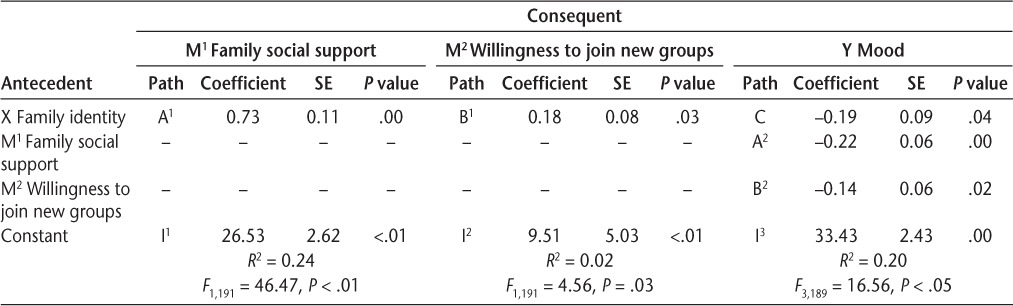

Mediation Analysis

From a simple multiple mediator mediation analysis constructed using ordinary least squares regression, family identity influenced mood indirectly through its effect on social support and willingness to join new groups. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 4, participants' family identity positively predicted levels of social support (β = 0.73, P < .01). Social support levels were also found to predict mood levels (β = −0.22, P < .01). Family identity was found to predict willingness to join new groups (β = −0.18, P < .05). Willingness to join new groups was found to predict mood levels (β = −0.14, P < .05). A bias-corrected CI for the indirect effect (β = −0.16) of family identity of mood through social support (based on 5000 bootstrap samples) was entirely below zero (95% CI, −0.27 to −0.08). A bias-corrected CI for the indirect effect (β = −0.03) of family identity of mood through willingness to join new groups (based on 5000 bootstrap samples) was entirely below zero (95% CI, −0.07 to −0.001). There was also evidence that family identity influenced mood independent of the mediating effect of social support and willingness to join new groups (β = 0.19, P < .05).

Figure 2.

Model with regression coefficients

Table 4.

Model coefficients

The results of the mediation analysis showed that family identity predicted mood through the parallel mediators of family social support and willingness to join new groups.

Discussion

In accordance with previous research showing that people with MS have higher rates of depression1,2 and anxiety3,4 than people with other neurologic conditions or the general population, this was also evident in the present study. We found that family identity was negatively associated with mood. Increases in family identity were associated with lower scores on the HADS, which can be interpreted as better overall mood. A mediation analysis further showed that family identity predicted mood through the parallel mediators of family social support and willingness to join new groups.

Several theoretical implications can be derived from the results. One of the more important implications can be seen in the direct effect of family identity on mood. In line with the SIMIC, identifying with the family group had a positive effect by reducing mood scores. This finding can help explain why the family is often a salient factor in adjustment to MS, as identifying with the family group seems to protect people with MS from the harmful effects of identity change after the life-changing transition of being diagnosed as having the disease.

Social support from the family group and willingness to join new groups were found to mediate the relationship between family identity and mood. Previously established identities provide a basis for drawing social support and a good platform for people to establish new identities that are compatible and integrated with old identities to enhance identity continuity.9 The mediating effects in this model have shown that family identity has an effect on mood through the mediators of increased family social support and increased willingness to join new groups, in accordance with the SIMIC9; although this has been implicated in adjustment to MS, it has so far been investigated only in a qualitative study.14

Although future longitudinal research is still needed, the results of this study could have clinical implications. Involving the family in the early stages of diagnosis and treatment of MS could increase social support for the person with MS, potentially reducing the negative effects of MS on mood. Similarly, educating family members on how to successfully provide social support could lead to the person with MS feeling greater identification with the family group and a reduction in low mood.

The main strength of this study was the size of the sample. Using both an NHS MS database and an online questionnaire resulted in a large number of people taking part in the study. A limitation of this study is the use of the Exeter Identity Transition Scales to measure willingness to join new groups. There are no established questionnaires to measure connectedness to others, and because of this, the decision was made to measure attempts to join newly established groups using the new groups subscale of the Exeter Identity Transition Scales. Although using an NHS MS database resulted in a larger sample size, this may have included more people in the early stages of the disease, complicating the validity of the sample. The return rate of completed questionnaires was 37.75%. In an attempt to increase the size of the sample, an online version of the questionnaire was created. The online version of the questionnaire was hosted on the research section of the MS Society website, but the response rate to this version is unknown.

There are several implications of this study. First, family support in response to MS diagnosis may be more beneficial than is currently understood. A variety of UK MS charities provide bibliotherapy on the use of the family in support after diagnosis.20,21 Involving the family in the early stages of diagnosis and treatment of MS could increase support for the individual and reduce the high prevalence of mood disorders. Second, family identity and family social support are highly correlated constructs. Although the direction of the association cannot be established by simply examining a correlation, teaching family members how to successfully provide social support to the family member with MS could lead to greater identification with the family group and a reduction in low mood. However, this would need to be examined in further research. Third, after increasing support from the family group and after a period of adjustment, families could be taught how to encourage participation in other social groups. By taking part in new groups, the person with MS may be able to further incorporate their identity continuity by establishing new identities that are compatible and integrated with the family identity.

A longitudinal investigation of the effects of family identity is required to further understand the effects of previously established social groups on the reduction of the negative effects of identity change.

PRACTICE POINTS

Family identity predicts mood in people with MS through social support and connectedness to others.

The family and the wider social context should be considered in relation to low mood in people with MS.

Involving the family in the early stages of diagnosis and treatment of MS could increase support for the individual and reduce the high prevalence of mood disorders.

Financial Disclosures:

Dr. Barker's PhD studentship was funded by the MS Society (966/12).

Funding/Support:

None.

References

- 1. Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, van der Meché FG, Passchier J, Hintzen RQ.. Impact of recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis on quality of life, anxiety, depression and distress of patients and partners. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003; 108: 389– 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegert RJ, Abernethy DA.. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005; 76: 469– 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zorzon M, de Masi R, Nasuelli D, . et al. Depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and MRI study in 95 subjects. J Neurol. 2001; 248: 416– 421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maurelli M, Marchioni E, Cerretano R, . et al. Neuropsychological assessment in MS: clinical, neuropsychological and neuroradiological relationships. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992; 86: 124– 128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fruehwald S, Loeffler-Stastka H, Eher R, Saletu B, Baumhackl U.. Depression and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001; 104: 257– 261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boeije HR, Duijnstee MS, Grypdonck MH, Pool A.. Encountering the downward phase: biographical work in people with multiple sclerosis living at home. Soc Sci Med. 2002; 55: 881– 893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haslam C, Holme A, Haslam SA, Iyer A, Jetten J, Williams WH.. Maintaining group memberships: social identity continuity predicts well-being after stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008; 18: 671– 691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Antonak RF, Livneh H.. Psychosocial adaptation to disability and its investigation among persons with multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1995; 40: 1099– 1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jetten J, Panchana N.. Not wanting to grow old; a social identity model of identity change (SIMIC) analysis of driving cessation among older adults. : Jetten J, Haslam AS, Haslam C, . The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being. Hove, UK, and New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barker AB, das Nair R, Lincoln NB, Hunt N.. Social identity change in people with multiple sclerosis: a meta-synthesis of qualitative literature. Soc Care Neurodisabil. 2014; 5: 256– 267. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen S, Pressman S.. Stress-buffering hypothesis. : Anderson NB, . Encyclopedia of Health and Behavior. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004: 780– 782. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wineman M. Adaptation to multiple sclerosis: the role of social support, functional disability, and percieved uncertainty. Nurs Res. 1990; 39: 294– 299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T.. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009; 29: 141– 153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Irvine H, Davidson C, Hoy K, Lowe-Strong A.. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: exploration of identity redefinition. Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31: 599– 606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doosjie B, Ellemers N, Spears R.. Perceived intergroup variability as a function of group status and identification. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1995; 31: 410– 436. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK.. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52: 30– 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP.. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67: 361– 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Atkins L, Newby G, Pimm J.. Normative data for the hospital anxiety and depression scales (HADS) in multiple sclerosis. Soc Care Neurodisabil. 2012; 3: 172– 178. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes AF. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Multiple Sclerosis Society. . Caring for Someone with MS: A Handbook for Family and Friends. London, UK: Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Multiple Sclerosis Trust. . A short guide to understanding my MS. https://support.mstrust.org.uk/file/a-short-guide-to-understanding-my-ms.pdf. 2014. Accessed January 29, 2018.