ABSTRACT

Fibronectin (FN) is a high-molecular-weight extracellular matrix protein that contains the RGDS motif, which is required to bind to integrins. Synthetic RGDS peptides have been reported to compete with FN to bind to the cell surface and inhibit the function of FN. Here, we identified that synthetic RGDS peptides significantly inhibit human enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection in cell cultures. In addition, mice treated with RGDS peptides and infected with EV71 had a significantly higher survival rate and a lower viral load than the control group. Because RGDS peptides affect the function of FN, we questioned whether FN may play a role in virus infection. Our study indicates that overexpression of FN enhanced EV71 infection. In contrast, knockout of FN significantly reduced viral yield and decreased the viral binding to host cells. Furthermore, EV71 entry, rather than intracellular viral replication, was blocked by FN inhibitor pretreatment. Next, we found that FN could interact with the EV71 capsid protein VP1, and further truncated-mutation assays indicated that the D2 domain of FN could interact with the N-terminal fragment of VP1. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the host factor FN binds to EV71 particles and facilitates EV71 entry, providing a potential therapy target for EV71 infection.

IMPORTANCE Hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks have occurred frequently in recent years, sometimes causing severe neurological complications and even death in infants and young children worldwide. Unfortunately, no effective antiviral drugs are available for human enterovirus 71 (EV71), one of the viruses that cause hand, foot, and mouth disease. The infection process and the host factors involved remain unknown, although several receptors have been identified. In this study, we found that the host factor fibronectin (FN) facilitated EV71 replication by interacting with EV71 particles and further mediated their entry. The RGDS peptide, an FN inhibitor, significantly inhibited EV71 replication in both RD cells and mice. In conclusion, our research identified a new host factor involved in EV71 infection, providing a new potential antiviral target for EV71 treatment.

KEYWORDS: EV71, fibronectin, viral entry

INTRODUCTION

Integrins, a family of adhesion receptors, bind to a variety of extracellular ligands. They recognize the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif within their ligands, including fibronectin (FN) (1, 2). Synthetic peptides containing the RGD sequence have been shown to compete with FN for binding to the cell surface and thus inhibit some cell function (3). It has been reported that RGDS peptides inhibit the aggregation of platelets by binding to integrin αIIbβ3, thus inhibiting thrombosis (4). In addition, synthetic RGDS peptides attenuate lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pulmonary inflammation and fulminant hepatic failure in mice by inhibiting integrin-signaled mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways (5, 6). RGDS peptides also attenuate mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury in rats (7). However, the effects of RGDS peptides on virus infection have not been elucidated. In our study, we found that synthetic RGDS peptides significantly inhibit EV71 infection.

FN is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein composed of type I, II, and III repeating units, and the two forms of FN, soluble plasma FN and insoluble cellular FN, are structurally and functionally different. Soluble plasma FN dimers are secreted in an inactive form that must be activated by interaction with α5β1 and other integrins in order to be assembled into an insoluble form via a complex mechanism (8, 9). Cellular FN is a major component of extracellular matrices (ECM) and functions in morphogenesis, cell migration, inflammation, and surface receptor internalization (10). The multidomain structure of FN allows it to bind simultaneously to cell surface receptors, e.g., integrins, collagen, proteoglycans, and other focal adhesion molecules (11). A number of bacteria, protozoa, and fungi express FN binding proteins that interact with cellular FN (12–14), and some even use cellular FN for intracellular invasion (15). Previous studies have suggested that FN participates in the production of hepatitis B virus (HBV), influenza A virus (IAV), and rhabdoviruses, including infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) and viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) (16–19). However, whether or not FN plays a role during human enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection has remained unknown. Here, we show that FN binds to EV71 and mediates EV71 entry.

EV71 causes major outbreaks of hand, foot, and mouth disease in children worldwide and is associated with neurological and systemic complications. Although the disease is present in most countries, the largest outbreaks have occurred in the Asia-Pacific region, for reasons that are not entirely understood (20–23). EV71 is a small, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of approximately 7,500 nucleotides. The RNA genome has a single open reading frame encoding a polyprotein, which can be cleaved into 11 proteins: four capsid proteins, VP1 to VP4, and seven nonstructural proteins, 2A to 2C and 3A to 3D. One of the capsid proteins, VP1, contributes to virulence and neurotropism and is involved in viral entry (24–26).

The externalized N terminus of EV71 VP1 anchors to the cell membrane, while the cleft around Gln-172 on VP1 interacts with exon 4 of scavenger receptor class B member 2 (SCARB2) (27–31). Other cellular receptors such as P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), sialylated glycans, heparan sulfate, nucleolin, and annexin II enhance either the attachment of EV71 to cells or the establishment of infection (32–36). Although multiple EV71 receptors have been identified, no antireceptor or anti-attachment molecule antibodies can completely block EV71 infection of host cells (37). Thus, previously unknown receptors or cofactors that mediate the binding and infection of EV71 remain to be identified.

RESULTS

Synthetic RGDS peptides significantly inhibit EV71 replication.

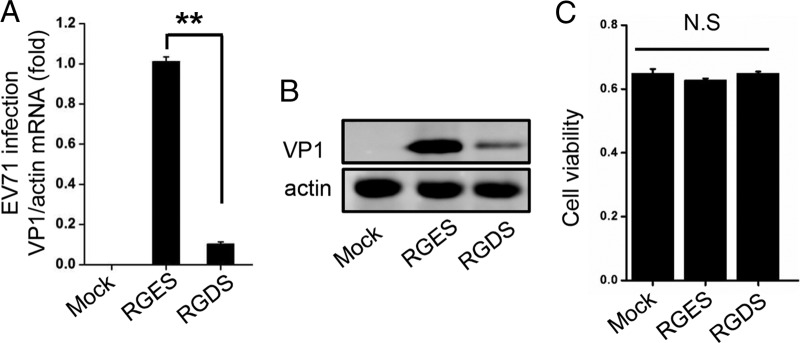

During our previous study, we accidentally found that synthetic Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (RGDS) peptides can significantly inhibit EV71 replication. Tetrapeptides can affect some cell functions by competing with adhesive proteins for binding to integrin receptors. It has been reported that RGDS peptides can inhibit thrombosis and that integrin signals MAP kinase pathways (5, 6). In our study, RD cells were pretreated with RGDS peptides and the control peptide RGES at the concentration of 5 mg/ml for 9 h and infected with EV71. The levels of EV71 VP1 mRNA were notably decreased by RGDS (Fig. 1A). Further Western blotting results showed that RGDS peptides indeed decreased EV71 replication (Fig. 1B). To exclude the potential effects of RGDS and RGES peptides on cell growth, we measured cell viability and found no significant cytotoxicity due to the peptide pretreatment (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Synthetic RGDS peptides significantly inhibit EV71 replication. RD cells were pretreated with RGDS and RGES peptides at a concentration of 5 mg/ml for 9 h. (A and B) Cells were infected with EV71 (MOI = 1) and harvested for RNA analysis (A) and Western blotting (B). (C) Cells were measured for cell viability by MTT assay, and the unit of the y axis is the readout optical density (OD) value. N.S, not significant. The data are representative of the means and standard deviations (error bars) for three samples per group (**, P < 0.01). All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

The RGDS peptide suppresses mouse-adapted EV71 infection in mice.

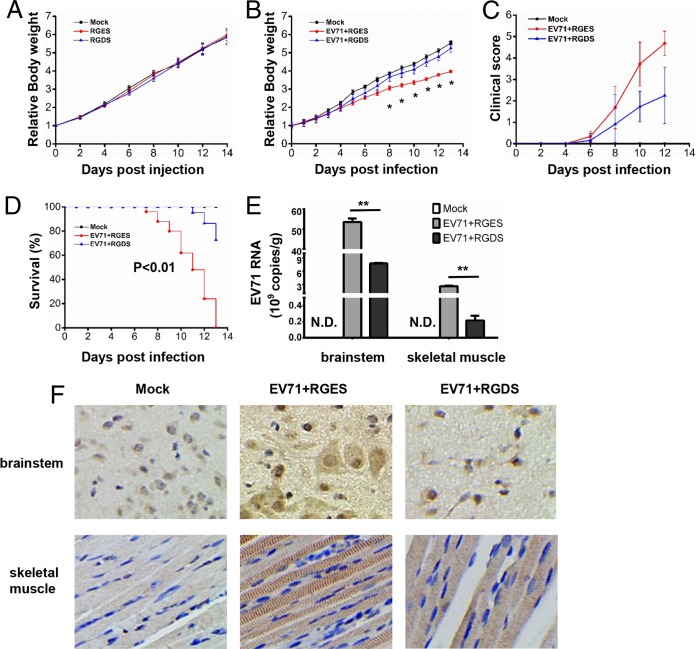

To further confirm our finding that the RGDS peptides inhibit EV71 replication, we conducted a series of experiments in mice. First, we examined the potential effects of the RGDS peptides on mouse body weight and health and found that compared to mock treatment or RGES treatment, RGDS did not significantly affect mouse health or body weight (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

RGDS impairs MA-EV71 infection in mice. (A) One-day-old BALB/c mice were mock injected (n = 7) or i.p. injected with PBS containing RGES (5 mg/kg) (n = 8) or RGDS (n = 7) (5 mg/kg). Body weight changes were monitored every other day, and the average weights at the time point of injection were set as 1. (B, C, D) One-day-old BALB/c mice were mock infected (n = 14) or infected via i.p. injection with 1 × 107 PFU mouse-adapted EV71 along with RGES (n = 23) or RGDS (n = 21) (5 mg/kg). Body weight changes (B) and clinical symptoms (C) of the mice were monitored every day. The clinical scores were defined as follows: 0, healthy; 1, ruffled hair and hunchbacked; 2, limb weakness; 3, paralysis in one limb; 4, paralysis in both limbs; and 5, death. (D) Survival was monitored for the indicated periods. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted using Origin 9, and the difference between the RGES-treated infected mice and the RGDS-treated infected mice was statistically significant as determined by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test analysis. (E, F) One-day-old BALB/c mice were mock infected (n = 9) or infected via i.p. injection with 1 × 107 PFU mouse-adapted EV71 along with RGES (n = 9) (5 mg/kg) or RGDS (n = 10) (5 mg/kg). The mice were euthanized at 8 dpi. Viral loads in the brainstem and skeletal muscle were quantified by qRT-PCR. N.D., not detectable (E). The viral antigen VP1 in the brainstem and skeletal muscle was examined by IHC; magnification, ×200 (F). The error bars indicate the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

Suckling mice were infected with mouse-adapted EV71 (MA-EV71) to further investigate the role of RGDS in EV71 infection. One-day-old suckling mice were mock infected or infected with MA-EV71 along with RGES or RGDS (5 mg/kg of body weight) (5) and then monitored for disease development. Loss of total body weight was detected starting at 8 days postinfection (dpi) in EV71-infected and RGES-treated mice, but not RGDS-treated mice, compared to the mock-infected group, and RGDS-treated infected mice nearly recovered their body weight (Fig. 2B). Mice were observed for a characteristic progression of severity of clinical symptoms, including ruffled hair and hunchbacked posture, limb weakness, paralysis in one limb, paralysis in both limbs, and death. The average clinical score in the RGDS-treated infected mice was significantly lower than that in the RGES-treated infected mice, suggesting that disease severity is suppressed by the RGDS peptide (Fig. 2C). EV71-infected mice began to die at 7 dpi, and none survived beyond 13 dpi. In contrast, mice treated with RGDS survived longer, with approximately 25% of mice dying by 13 dpi (Fig. 2D).

Mouse tissues, including the brainstem and skeletal muscle, were examined for viral load by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). We found that viral RNA in the brainstem and skeletal muscle of infected mice was greatly decreased in the presence of RGDS compared to RGES (Fig. 2E). In addition, both the brainstem and skeletal muscle of infected mice had slightly weaker EV71 VP1 staining in the RGDS treatment group than in the RGES treatment group (Fig. 2F). In summary, the RGDS peptide suppressed EV71 infection in suckling mice and increased their survival rate.

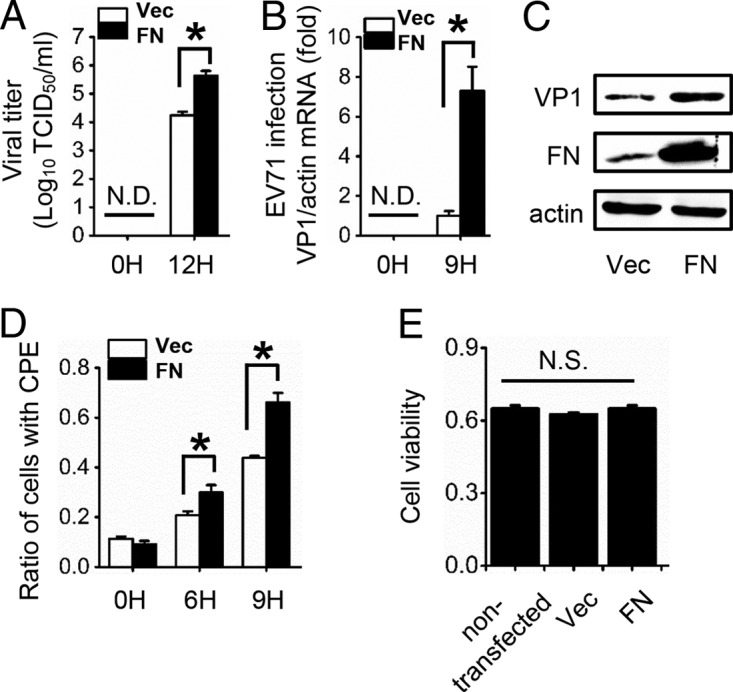

FN increases the yield of EV71.

It has been reported that RGDS is the minimal sequence for FN protein recognition and binding to integrins (2, 5). FN participates in the production of HBV, IAV, and rhabdoviruses, including IHNV and VHSV (16–19). Our previous study also revealed that FN facilitates HBV replication through inhibiting endogenous alpha interferon (IFN-α) production and promoting HBV enhancer (18). We speculated that the mechanism by which RGDS inhibits EV71 replication may be through interfering with the function of FN. Consistent with our speculation, the results showed that FN indeed facilitated EV71 replication. Overexpression of FN significantly increased the titer of EV71 in RD cell supernatants (Fig. 3A). In addition, cellular EV71 RNA (Fig. 3B) and VP1 protein (Fig. 3C) levels were elevated in RD cells overexpressing FN. The virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) was monitored in RD cells transfected with an empty vector or FN at 0, 6, and 9 h postinfection (hpi). The quantitative data showed that virus-induced CPE in cells transfected with FN significantly increased compared to CPE in cells transfected with empty vector at 6 and 9 hpi (Fig. 3D). In order to exclude the potential effect of FN overexpression on cell growth, we measured cell viability and found no significant cytotoxicity due to FN transfection (Fig. 3E). Our results consistently showed that FN positively upregulated EV71 production.

FIG 3.

FN expression upregulates EV71 proliferation. RD cells were transfected with empty vector or FN expression plasmid for 24 h and then infected with EV71 (MOI = 1). (A) Viral titers in the supernatant were measured at 0 and 12 hpi. (B) The infection of RD cells was quantified by qRT-PCR at 0 and 9 hpi. (C) EV71 VP1 and FN expression was determined by immunoblot analysis at 9 hpi. (D) CPE induced by EV71 in RD cells at 0, 6, and 9 hpi, as well as the ratio of cells with CPE, are shown. (E) RD cells transfected with or without the indicated plasmids were measured for cell viability by MTT assay, and the unit of the y axis is the readout OD value. N.D., not detectable. N.S., not significant; Vec, vector. The data are representative of the means and standard deviations (error bars) of three samples per group (*, P < 0.05). All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

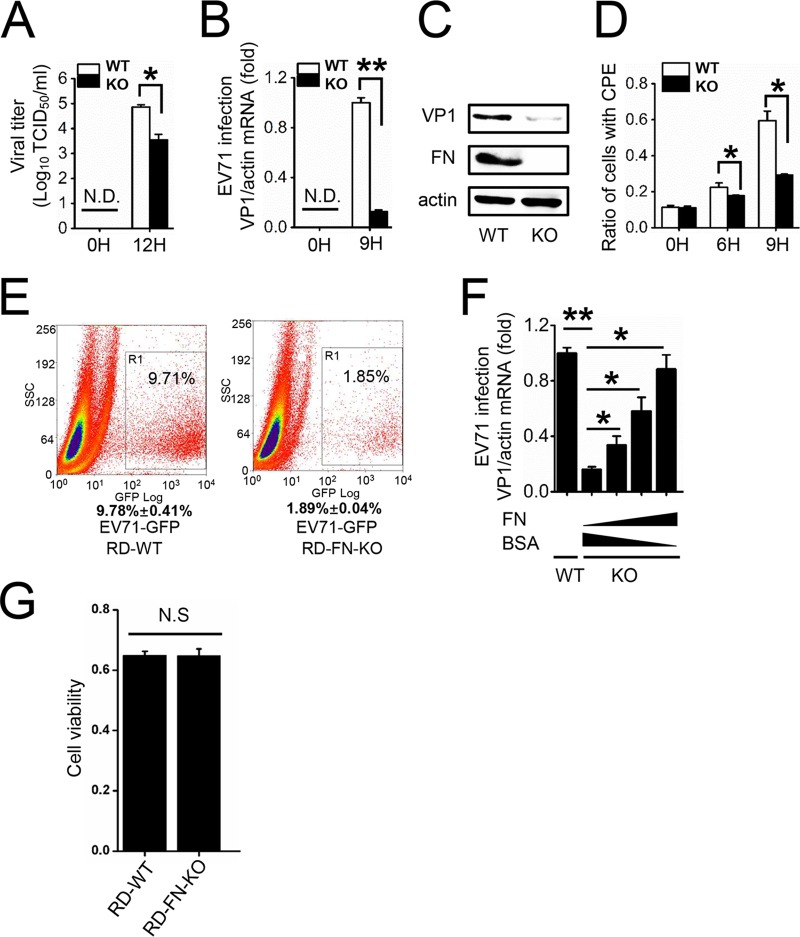

Depletion of FN inhibits EV71 infection.

We then constructed an FN knockout (FN-KO) cell line in RD cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system to further explore the effects of endogenous FN on EV71 virus proliferation (38). We found that the titer of EV71 was significantly decreased in FN-KO cell supernatants compared to wild-type (WT) RD cells (Fig. 4A), and EV71 VP1 mRNA and protein levels were markedly suppressed in FN-KO cells compared to those of WT cells (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, virus-induced CPE in FN-KO cells significantly decreased compared with that of WT RD cells at 6 and 9 hpi (Fig. 4D). We then infected WT and FN-KO RD cells with EV71-green fluorescent protein (GFP) virus for 24 h and performed flow cytometry, which revealed that 9.78% ± 0.41% of the WT cells were infected with EV71-GFP, whereas only 1.89% ± 0.04% of FN-KO cells were infected (Fig. 4E). To further confirm the role of FN in EV71 infection, the level of FN was restored in FN-KO cells by adding intact FN protein, which was isolated from human plasma. As the results showed, EV71 infection was restored by exogenous FN in a dose-dependent manner. (Fig. 4F). No significant cytotoxicity was observed in the FN-KO cells when cell viability was measured (Fig. 4G). Taken together, our results demonstrate that FN facilitates EV71 infection in vitro.

FIG 4.

Knockout of FN decreases the yield of EV71. WT or FN-KO RD cells were infected with EV71 (MOI = 2). (A) Viral titers in the supernatant were measured at 0 and 12 hpi. (B) The infection of RD cells was quantified by qRT-PCR at 0 and 9 hpi. (C) EV71 VP1 and FN expression was determined by immunoblot analysis at 9 hpi. (D) CPE were induced by EV71 in RD cells at 0, 6, and 9 hpi, and the ratio of cells with CPE are shown. (E) Flow cytometry studies of the WT or FN-KO RD cells infected with EV71-GFP virus (MOI = 5) for 24 h. The frames indicate the virus-infected cells, and the ratio of infected cells is indicated in the inset. The data below the frames are representative of the means and standard deviations (error bars) for three samples per group. SS, side scatter. (F) WT or FN-KO RD cells were preincubated with BSA or FN protein for 6 h and then infected with EV71 (MOI = 2). The infected RD cells were collected and quantified by qRT-PCR at 9 hpi. (G) Cell viability of WT or FN-KO RD cells was determined by MTT assay, and the unit of the y axis is the readout OD value. N.D., not detectable. N.S., not significant. The data are representative of the means and standard deviations (error bars) of three samples per group (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

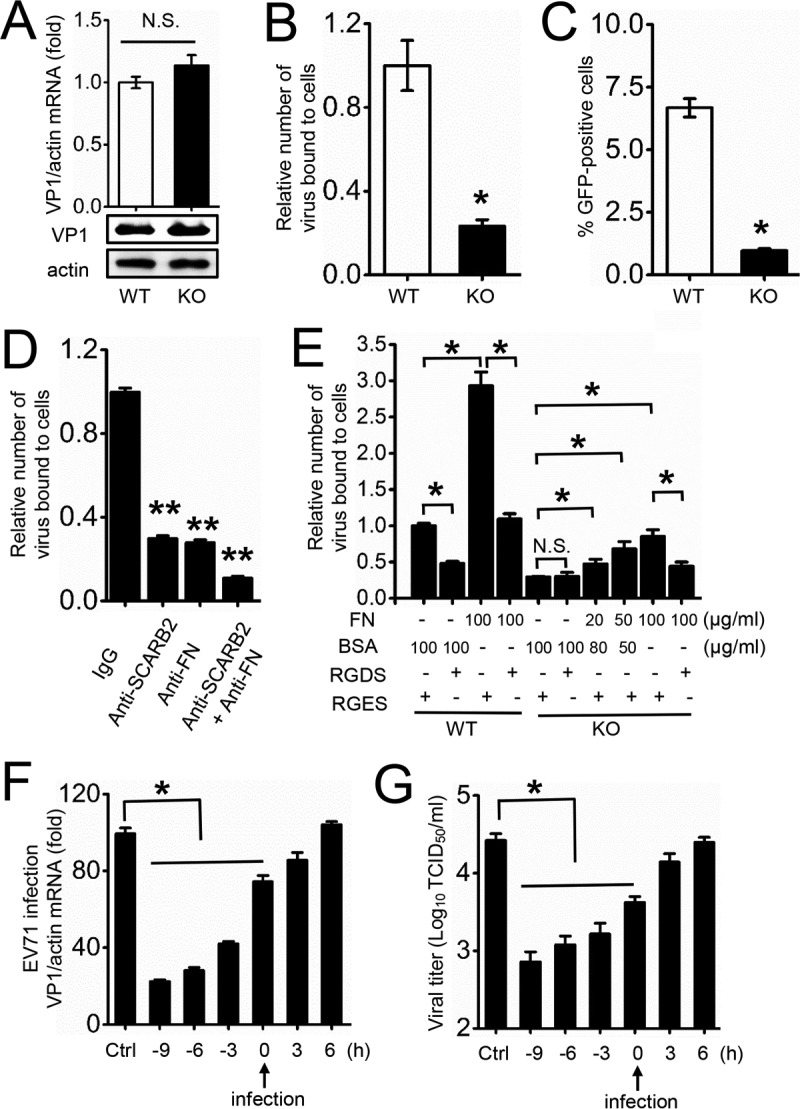

Knockout of FN reduces EV71 binding affinity to host cells.

The observation that FN upregulates EV71 proliferation prompted us to further investigate the viral life cycle stage at which FN is involved. We transcribed infectious RNAs in vitro from linearized infectious replicons and transfected them into WT or FN-KO RD cells. At 24 h posttransfection, the RD cells showed typical CPE, and we found no significant variation between cellular EV71 RNA or VP1 protein levels in WT or FN-KO cells (Fig. 5A). These data suggest that the EV71 RNA replication inside the host cells was not affected by the knockout of FN. Therefore, next, we performed a binding assay to assess whether FN influences viral attachment and found that the binding affinity of EV71 to FN-KO cells was approximately 75% less than to WT cells (Fig. 5B). In addition, flow cytometry studies have revealed that EV71-GFP binds more weakly to FN-KO cells than to WT RD cells (Fig. 5C). We also observed decreased levels of bound EV71 virus upon treatment of the cells with anti-SCARB2 and/or anti-FN antibody (Fig. 5D). SCARB2 is a known receptor required for the attachment of EV71 and was used as a positive control. The data indicate that FN plays a comparatively important role to SCARB2 for EV71 binding. Neither anti-SCARB2 nor anti-FN treatment completely abolished virus binding, which suggested that other virus binding molecules exist on the RD cell surface. Additionally, antibody blocking SCARB2 and/or FN also inhibited the EV71-GFP virus infection (data not shown). All these results implied that FN may be involved in EV71 binding to the host cells.

FIG 5.

FN increases the efficiency of EV71 binding to host cells, but not intracellular viral replication. (A) The EV71 infectious replicon SDLY107RV was transcribed in vitro and transfected into WT or FN-KO RD cells for 24 h. EV71 VP1 expression was then determined by qRT-PCR or immunoblot analysis in cell lysates of WT or FN-KO RD cells. N.S., not significant. (B) Binding assay of EV71 virions (MOI = 20) with WT or FN-KO RD cells. Bound virus was measured by qRT-PCR, and the value of the control group was set as 1. (C) Binding assay of EV71-GFP virions (MOI = 20) with WT or FN-KO RD cells. The ratio of GFP-positive cells was measured by flow cytometry. (D) RD cells were preincubated with anti-SCARB2 (5 μg/ml) and/or anti-FN (5 μg/ml) antibody, or IgG (5 μg/ml) for 6 h, followed by EV71 binding, and then bound virus was measured by qRT-PCR, and the value of the control group was set as 1. (E) Binding assay of EV71 virions (MOI = 20) with WT or FN-KO RD cells pretreated with BSA, FN protein (at the indicated concentrations), RGES, or RGDS (5 μg/ml) for 9 h. Bound virus was measured by qRT-PCR, and the value of the control group was set as 1. (F, G) Effects of adding oligopeptide RGES (control, 5 μg/ml, −6 h) or RGDS (treatment group, 5 μg/ml) at various times during the EV71 replication cycle. RD cells were infected with EV71, and the RGDS was then added at −9, −6, −3, 0, 3, and 6 hpi. Infection of RD cells was quantified by qRT-PCR at 9 hpi (G). Viral titers in the supernatant were measured at 12 hpi (H). The data are representative of the means and standard deviations (error bars) for three samples per group (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

To further investigate the role of FN in EV71 infection, we examined the effects of RGDS on EV71 binding to FN-WT or FN-KO cells. The result showed that RGDS, but not RGES, can block virus binding to FN-WT cells but not FN-KO cells (Fig. 5E), suggesting that RGDS is specific for FN during EV71 binding to the host cells, although RGD motifs are reported to be present within several proteins (39–42). Exogenous FN protein was used as a positive control, and the binding affinity of EV71 to FN-KO cells was partially rescued after the restoration of the FN expression (Fig. 5E). We next infected RD cells with EV71 and treated them with RGDS or RGES at −9, −6, −3, 0, 3, and 6 hpi (0 hpi = time of virus addition). Both the cellular EV71 RNA levels and viral titers indicated that EV71 was inhibited in a time-dependent manner by RGDS. RGDS, but not RGES, treatment at −9, −6, and −3 hpi significantly inhibited EV71 proliferation; treatment at 0 hpi had a moderate inhibitive effect, and after 3 hpi, the anti-EV71 effect was significantly attenuated (Fig. 5F and G). Taken together, the data suggest that FN is involved in the early steps of EV71 infection, such as attachment and binding, but not genome replication.

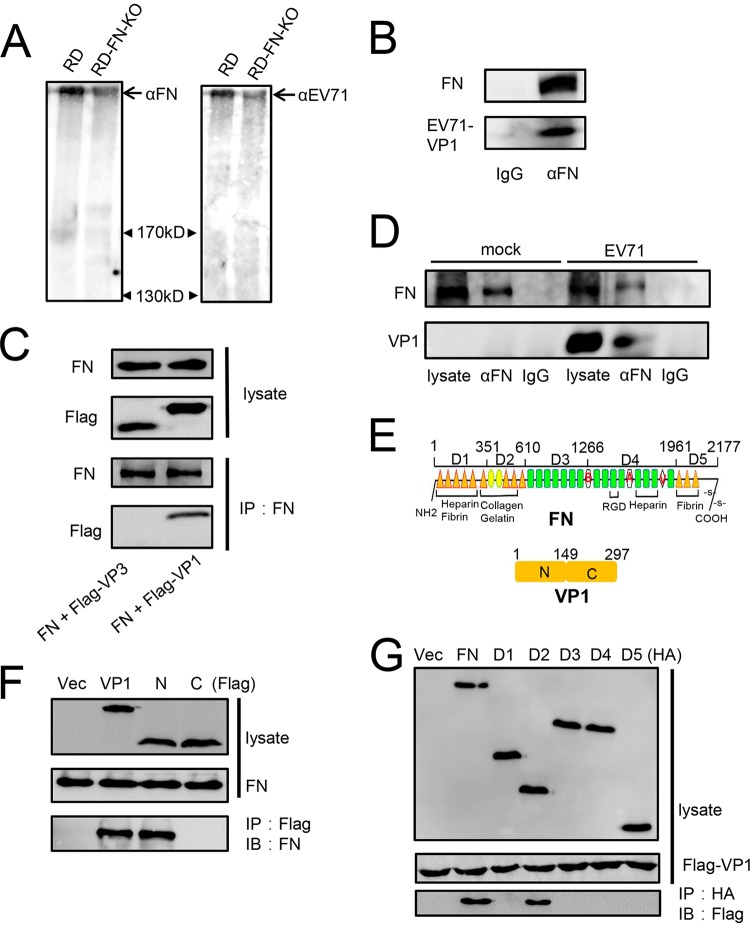

FN can interact with EV71 VP1.

Since FN facilitates EV71 replication by increasing its binding affinity to host cells, we wondered whether FN interacts with EV71 particles directly or indirectly. Our hypothesis was confirmed by an EV71 virus overlay protein binding assay (VOPBA) (Fig. 6A). As the result shows, the place of the band detected in the EV71 particles on the blotted membrane is the same as the band detected with FN antibody, which indicated that EV71 particles interacted with FN directly; RD-FN-KO cells were used as a negative control. To further verify our hypothesis, we incubated EV71 particles, FN proteins, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4°C, and then protein G-agarose and the indicated antibodies were added. The results showed that the anti-FN antibodies can immunoprecipitate not only FN but also EV71 particles (Fig. 6B). Next, exogenous coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that VP1, but not VP3, of EV71 could interact with FN (Fig. 6C). We then assessed the interaction of FN and VP1 in RD cells during EV71infection and found that VP1 was indeed associated with FN in infected cells, as demonstrated by immunoprecipitation with anti-FN antibody (Fig. 6D). The schematic map in Fig. 6E shows truncated mutation constructs of FN and VP1. We found that FN associated with the N terminus of VP1 (Fig. 6F) and VP1 bound to the D2 domain of FN (Fig. 6G).

FIG 6.

FN interacts with EV71 VP1. (A) RD and RD-FN-KO cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting (left) with anti-FN antibodies (left) and VOPBA with anti-EV71 VP1 antibodies (right). The arrows indicate bands observed on the membrane. (B) FN protein (1.5 μg), EV71 virions (5 × 106 viral genome copies), and BSA (20 μg) were incubated at 4°C overnight with constant agitation and immunoprecipitated with anti-FN antibody/isotype IgG and protein G-agarose; after being washed five times with washing buffer, the samples were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-FN and anti-EV71 VP1 antibodies. (C) The lysates of 293T cells transfected with Flag-VP1 or Flag-VP3 along with the FN plasmid were harvested at 24 h posttransfection and immunoprecipitated with anti-FN antibodies prior to immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibodies. (D) The lysates of EV71-infected RD cells (MOI = 2) were harvested at 12 hpi and immunoprecipitated with anti-FN antibodies prior to immunoblotting with anti-VP1. (E) Schematic map of the domains and truncated mutations of FN and VP1. (F) The lysates of 293T cells transfected with empty vector, Flag-VP1, and truncated VP1 mutations along with FN were harvested at 24 h and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibodies prior to immunoblotting with anti-FN antibodies. (G) The lysates of 293T cells transfected with empty vector, FN, and truncated FN mutations along with VP1 were harvested at 24 h and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies prior to immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibodies. All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results.

DISCUSSION

Many integrins recognize the RGD motif within their ligands, including FN, fibrinogen, vitronectin, von Willebrand factor, and collagens (5). Therefore, synthetic RGDS peptides, which compete with these integrin ligands for binding to integrin receptors, can inhibit some cell function. For example, RGDS peptides have been shown to inhibit the aggregation of platelets and attenuate LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting integrin-signaled MAP kinase pathways (4–7). In our study, we first identified that RGDS peptides can significantly inhibit EV71 replication in RD cells (Fig. 1) and mice treated with RGDS and infected with EV71 had a higher survival rate and lower viral load in the brainstem and skeletal muscles than did the control group (Fig. 2). Therefore, the RGDS peptide might be a new potential drug for treating EV71 infection, but the concentrations of the RGDS peptide that we used in ex vivo and in vivo experiments are 5 mg/ml and 5 mg/kg, respectively. This dose is somewhat high, and much exploration is needed to apply the peptide to clinical therapy. In our previous study, we found that FN, which is stimulated by HBV, facilitates HBV replication through inhibiting endogenous IFN-α production and promoting HBV enhancers (43). FN has also been reported to facilitate the entry of gammaretrovirus, influenza A virus, and rhabdoviruses, including IHNV and VHSV (16, 18, 19, 44).

FN is ubiquitously expressed and participates in multiple functions, such as morphogenesis, cell migration, inflammation, and surface receptor internalization (10), and plays a role in H1N1 influenza virus and HBV infection (19, 45). We tested the effects of FN on EV71 infection. Consistently with our hypothesis, overexpression of FN was found to facilitate EV71 replication (Fig. 3), and knockout of FN had the opposite effect (Fig. 4).

Because of the location of FN, the stage at which FN affects EV71 infection may be extracellular entry. The experiment in Fig. 5 shows that FN has no effect on intracellular infection. And the following experiments identify that FN increases EV71 binding affinity to host cells. Cells pretreated with RGDS peptides were found to bind to fewer virus particles than did RGES-pretreated cells, a result that on the other hand identified that the mechanism by which RGDS inhibits EV71 replication is through the blocking of FN.

Among identified EV71 receptors, SCARB2 is a major receptor for all EV71 strains, as well as some enterovirus A species, and is widely expressed throughout the body (46, 47). Although the EV71 receptor PSGL-1 is expressed only in specific tissues, and only some EV71 strains or genotypes are able to attach to and infect PSGL-1-expressing cells (33, 47), PSGL-1 confers upon cells a higher binding affinity for EV71 (PSGL-1-binding strain) than SCARB2, which suggests that both receptors have the ability for robust viral infection (48). In our study, we identified that FN, a cell surface factor, binds to EV71 VP1 and enhances EV71 entry. Among the EV71 capsid proteins, VP1 is the most external, surface-accessible, and immunodominant protein. Previous study has revealed that the cleft around Gln-172 of VP1 associates with amino acids 144 to 151 of SCARB2 (27–31), while our study shows that the N terminus of VP1 can interact with the D2 domain of FN. Whether or not the FN-VP1 association contributes to the interaction between VP1 and SCARB2 is interesting and remains to be clarified. The D2 domain of FN is the gelatin-binding region. It has been reported that transglutaminase 2 binds to the gelatin-binding domain of FN and acts as an integrin coreceptor (16). Streptococcus pyogenes F1 adhesin also interacts with the N-terminal 70-kDa fibrin- and gelatin-binding domain of FN and prevents assembly of an FN matrix (19). However, we found that the gelatin-binding region of FN can bind to EV71 VP1 and further increases its binding affinity to host cells, which may provide a target for blocking EV71 entry. Taken together, FN is an important factor of EV71 entry.

Data from previous studies suggest that FN expression is higher in infants than in adults (49, 50). This higher FN expression, in addition to a child's immature immune system, may be the reason why EV71 infects only children. Further investigation is needed to fully answer this question, while our results significantly advance our knowledge of virus-host interactions and provide a potential antiviral target for treating EV71 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

RD cells and HEK293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). RD-FN-KO cells were produced using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat(s) (CRISPR)-Cas9 system (38). Briefly, lentiviruses were harvested from the supernatants of HEK293 cells that were cotransfected with package plasmids pSP and pMD, along with lentiCRISPRv2, containing the target guide sequence of FN (5′-GGGACAGCGGTGCCCTCCAC-3′). Cells were infected with the lentivirus and screened with puromycin (0.9 μg/ml), and the surviving monocolony was selected. The monocolony was cultured, and FN and protein expression levels were determined. RD-FN-KO cells were obtained by amplification of the monocolony, which does not express FN, and maintained with puromycin (0.9 μg/ml). All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in medium according to ATCC instructions. WT EV71 has been described in a previous study (51), and EV71-GFP virus and the infectious EV71 replicon were kindly provided by Jianguo Wu (Wuhan University). The MA-EV71 strains were gifts from Zishu Pan (Wuhan University).

Antibodies and reagents.

Rabbit anti-EV71 polyclonal antibodies against VP1 (catalog number PAB7631-D01P; Abnova) were used to detect viruses in all experiments. Rabbit anti-FN polyclonal antibodies (catalog number 15613-1-AP), mouse anti-FN monoclonal antibodies (catalog number 66042-1-Ig), mouse anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibodies (catalog number 66240-1-Ig), and mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibodies (catalog number 60008-1-Ig) were purchased from Proteintech. Mouse anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) monoclonal antibodies (catalog number M132-3) and mouse anti-Flag monoclonal antibodies (catalog number M185-3L) were purchased from MBL International Corporation. Goat anti-SCARB2 polyclonal antibodies (catalog number AF1966-SP) were purchased from R&D Systems. The secondary antibodies used for Western blot analysis were purchased from Southern Biotech (horseradish peroxidase [HRP]-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [IgG], HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG [H+L]). RGDS peptides were purchased from Sigma, and the RGES peptides (catalog number AS-62527) were purchased from Anaspec Corporation. The RGDS was initially dissolved in double-distilled water (ddH2O), and stock solutions were stored at −80°C. FN proteins (catalog number F8180) were purchased from Solarbio Company. Immediately before addition to the cells, these compounds were diluted to the desired concentrations in serum-free minimum essential medium (MEM). TRIzol reagents were purchased from Invitrogen. The Amega script T7 high yield transcription kit was purchased from Ambion (catalog number AMB13345). An MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] kit was purchased from Beyotime (catalog number ST316).

Plasmids and transfection.

The coding region of FN was generated by PCR amplification. The PCR product was digested with NheI/HindIII and cloned directly into the pCDNA-3.1 Myc/His(+) expression vector to generate full-length pFN. Full-length or truncated fragments of FN were subcloned into PKH3-3×HA. Full-length or truncated fragments of SCARB2 were cloned into p3×Flag-CMV-14 or pCDNA-3.1 Myc/His(+). Full-length or truncated fragments of VP1 were cloned into p3×Flag-CMV-14. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

The cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105 cells per 24-well or 6-well plate, depending on the experiment, and were grown to 80% confluence prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions for 24 h and then either harvested or treated as required.

Virus titration.

Virus titers were determined using endpoint dilution assays (EPDA), with focus-forming units as the readout (52). In brief, 1 × 104 RD cells were seeded per well of a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated overnight. The EV71 virions were then serially diluted 10-fold (10−1 to 10−8) with fetal bovine serum (FBS)-free minimum essential medium (MEM; Life Technologies) and added to the RD cells. The plates were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. CPE was observed under the microscope 3 to 4 dpi. The virus titer, expressed as the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50), was determined by EPDA.

Virus infection.

Cells were plated in a 6-well plate overnight and were grown to approximately 80% confluence prior to EV71 infection. The cells were washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times to completely remove the serum contained in the medium and then incubated with serum-free MEM. The virus was diluted in serum-free MEM and incubated with the cells at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 2 h at 37°C. Then, the unbound virus was removed by washing three times, and the cells were maintained with serum-free MEM for the indicated times.

Virus binding assay.

A virus binding assay was performed as previously described (53). Briefly, cells were seeded in 6-well plates overnight. The following day, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed once with cold PBS. After that, 2 ml of binding buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide) was added to the cells on ice and incubated for 10 min; the supernatant was subsequently removed from the cells. The WT EV71 or EV71-GFP virus was diluted in serum-free MEM and added to the cells at the indicated MOI. After 1 h of incubation on ice, the unbound virus was removed by three wash steps with PBS, and the cells were either lysed in TRIzol for RNA analysis or digested for flow cytometry.

Virus overlay protein binding assay.

The VOPBA was performed as described by Su et al. (36). Briefly, RD and RD-FN-KO cell lysates were subjected to 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under nonreducing conditions and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, followed by blocking with 1% BSA. Then, the membranes were incubated with EV71 particles at 4°C overnight. After three washes, the membranes were incubated with anti-EV71 VP1 antibody at room temperature for 2 h and followed by incubation with the indicated HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

Immunoblot analysis and immunoprecipitation.

Immunoblot analysis was performed with cells lysed in a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors; the protein concentrations of the lysates were determined with a spectrophotometer. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Pall Corporation). The membranes were blocked for 4 h with 5% BSA (Sigma) solution in Tris-buffered saline. The membranes were then blotted with specific primary antibodies, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad). Cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes and lysed in 800 μl lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4 to 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with 0.1% (vol/vol) of a protease inhibitor mixture (Merck). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and were incubated overnight at 4°C with constant agitation with 0.5 μg of the indicated antibody cross-linked to 30 μl protein G-agarose. After extensive washing with lysis buffer, immunocomplexes were resuspended in 20 μl 1× SDS sample buffer for analysis by SDS-PAGE.

RNA analysis.

Total cellular RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Ambion) according to its standard protocol. Quantitative PCR assays were performed using the ABI StepOne real-time PCR system and SYBR RT-PCR kits (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for qPCR were as follows: VP1, 5′-AACGCACGTCATCTGGGATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCCAATCGGTGACTGCTCA-3′ (reverse); actin, 5′-TCTGTCAGGGTTGGAAAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAATGCAAACCGCTTCCAAC-3′ (reverse).

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was performed as previously reported (46), with some modifications. Briefly, the cells were trypsinized to produce a single-cell suspension and resuspended EV71-GFP-bound RD cells or EV71-GFP-infected RD cells in PBS containing 0.02% EDTA and then analyzed for GFP expression in the cells on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson and Company).

Mouse infection.

BALB/c mice were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center. The mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in individual ventilated cages. One-day-old suckling mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) mock infected or infected with 1 × 107 PFU of MA-EV71 in 50 μl PBS along with RGDS or RGES FN inhibitors. Following EV71 infection, the mice were scored as follows: 0, healthy; 1, ruffled hair and hunchbacked; 2, limb weakness; 3, paralysis in one limb; 4, paralysis in both limbs; and 5, death.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed with the Student t test (two-tailed) using Microsoft Excel. Differences were considered statistically significant at the following P values: **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed using a log rank test.

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize suffering. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan University (project license number WDSKY0201302).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jianguo Wu and Zishu Pan for the kind gifts they provided for this study.

This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570870), Chinese 111 project (B06018), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province Innovation Group (2017CFA022). The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection, or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kao WJ, Lee D. 2001. In vivo modulation of host response and macrophage behavior by polymer networks grafted with fibronectin-derived biomimetic oligopeptides: the role of RGD and PHSRN domains. Biomaterials 22:2901–2909. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J, Yao J, Chen J, Wang XN, Zhu TY, Chen LL, Chu P. 2009. Construction of drug screening cell model and application to new compounds inhibiting FITC-fibrinogen binding to CHO cells expressing human alphaIIbbeta3. Eur J Pharmacol 618:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabuchi A, Yoshioka A, Higashi T, Shirakawa R, Nishioka H, Kita T, Horiuchi H. 2003. Direct demonstration of involvement of protein kinase Calpha in the Ca2+-induced platelet aggregation. J Biol Chem 278:26374–26379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon C, Han JR, Park HJ, Hah JS, Kang JL. 2009. Synthetic RGDS peptide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting integrin signaled MAP kinase pathways. Respir Res 10:18. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin X, Gong X, Jiang R, Zhang L, Wang B, Xu G, Wang C, Wan J. 2014. Synthetic RGDS peptide attenuated lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced fulminant hepatic failure in mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29:1308–1315. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B, Wan JY, Zhang L, Min S. 2012. Synthetic RGDS peptide attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury in rats. Exp Lung Res 38:204–210. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2012.664835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE. 2005. Fibronectin fibrillogenesis, a cell-mediated matrix assembly process. Matrix Biol 24:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi S, Leiss M, Moser M, Ohashi T, Kitao T, Heckmann D, Pfeifer A, Kessler H, Takagi J, Erickson HP, Fassler R. 2007. The RGD motif in fibronectin is essential for development but dispensable for fibril assembly. J Cell Biol 178:167–178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh P, Carraher C, Schwarzbauer JE. 2010. Assembly of fibronectin extracellular matrix. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26:397–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh P, Schwarzbauer JE. 2012. Fibronectin and stem cell differentiation—lessons from chondrogenesis. J Cell Sci 125:3703–3712. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderete JF, Benchimol M, Lehker MW, Crouch ML. 2002. The complex fibronectin–Trichomonas vaginalis interactions and Trichomonosis. Parasitol Int 51:285–292. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5769(02)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson B, Nair S, Pallas J, Williams MA. 2011. Fibronectin: a multidomain host adhesin targeted by bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35:147–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klotz SA. 1992. Fungal adherence to the vascular compartment: a critical step in the pathogenesis of disseminated candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 14:340–347. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzies BE. 2003. The role of fibronectin binding proteins in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis 16:225–229. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann BR, Annis DS, Mosher DF. 2011. Reactivity of the N-terminal region of fibronectin protein to transglutaminase 2 and factor XIIIA. J Biol Chem 286:32220–32230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Ding X, Zhang Y, Bo X, Zhang M, Wang S. 2006. Fibronectin is essential for hepatitis B virus propagation in vitro: may be a potential cellular target? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 344:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Collodi P. 2002. Novel form of fibronectin from zebrafish mediates infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus infection. J Virol 76:492–498. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.492-498.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer LM, Tomasini-Johansson BR, Ma W, Annis DS, Eickstaedt NL, Ensenberger MG, Satyshur KA, Mosher DF. 2010. Extended binding site on fibronectin for the functional upstream domain of protein F1 of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem 285:41087–41099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu H, Utama A, Onnimala N, Li C, Li-Bi Z, Yu-Jie M, Pongsuwanna Y, Miyamura T. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71 infection in the Western Pacific Region. Pediatr Int 46:231–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2004.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardosa MJ, Perera D, Brown BA, Cheon D, Chan HM, Chan KP, Cho H, McMinn P. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of human enterovirus 71 strains and recent outbreaks in the Asia-Pacific region: comparative analysis of the VP1 and VP4 genes. Emerg Infect Dis 9:461–468. doi: 10.3201/eid0904.020395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, McMinn P, Ooi MH. 2010. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect Dis 10:778–790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordey S, L'Huillier AG, Turin L, Gervaix A, Posfay Barbe K, Kaiser L. 2015. Enterovirus and Parechovirus viraemia in young children presenting to the emergency room: unrecognised and frequent. J Clin Virol 68:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordey S, Petty TJ, Schibler M, Martinez Y, Gerlach D, van Belle S, Turin L, Zdobnov E, Kaiser L, Tapparel C. 2012. Identification of site-specific adaptations conferring increased neural cell tropism during human enterovirus 71 infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002826. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaini Z, McMinn P. 2012. A single mutation in capsid protein VP1 (Q145E) of a genogroup C4 strain of human enterovirus 71 generates a mouse-virulent phenotype. J Gen Virol 93:1935–1940. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043893-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss M, Filman DJ, Belnap DM, Cheng N, Noel RT, Hogle JM. 2015. Nectin-like interactions between poliovirus and its receptor trigger conformational changes associated with cell entry. J Virol 89:4143–4157. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03101-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fricks CE, Hogle JM. 1990. Cell-induced conformational change in poliovirus: externalization of the amino terminus of VP1 is responsible for liposome binding. J Virol 64:1934–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuthill TJ, Bubeck D, Rowlands DJ, Hogle JM. 2006. Characterization of early steps in the poliovirus infection process: receptor-decorated liposomes induce conversion of the virus to membrane-anchored entry-intermediate particles. J Virol 80:172–180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.172-180.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P, Song Z, Qi Y, Feng X, Xu N, Sun Y, Wu X, Yao X, Mao Q, Li X, Dong W, Wan X, Huang N, Shen X, Liang Z, Li W. 2012. Molecular determinants of enterovirus 71 viral entry: cleft around GLN-172 on VP1 protein interacts with variable region on scavenge receptor B 2. J Biol Chem 287:6406–6420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.301622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamayoshi S, Koike S. 2011. Identification of a human SCARB2 region that is important for enterovirus 71 binding and infection. J Virol 85:4937–4946. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02358-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogle JM. 2012. A 3D framework for understanding enterovirus 71. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang B, Chuang H, Yang KD. 2009. Sialylated glycans as receptor and inhibitor of enterovirus 71 infection to DLD-1 intestinal cells. Virol J 6:141. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Tano Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2009. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:794–797. doi: 10.1038/nm.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang SL, Chou YT, Wu CN, Ho MS. 2011. Annexin II binds to capsid protein VP1 of enterovirus 71 and enhances viral infectivity. J Virol 85:11809–11820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan CW, Poh CL, Sam IC, Chan YF. 2013. Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. J Virol 87:611–620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02226-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su PY, Wang YF, Huang SW, Lo YC, Wang YH, Wu SR, Shieh DB, Chen SH, Wang JR, Lai MD, Chang CF. 2015. Cell surface nucleolin facilitates enterovirus 71 binding and infection. J Virol 89:4527–4538. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03498-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel KP, Bergelson JM. 2009. Receptors identified for hand, foot and mouth virus. Nat Med 15:728–729. doi: 10.1038/nm0709-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruoslahti E. 1996. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. 2003. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials 24:4385–4415. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Lorenzi V, Sarra Ferraris GM, Madsen JB, Lupia M, Andreasen PA, Sidenius N. 2016. Urokinase links plasminogen activation and cell adhesion by cleavage of the RGD motif in vitronectin. EMBO Rep 17:982–998. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widhe M, Shalaly ND, Hedhammar M. 2016. A fibronectin mimetic motif improves integrin mediated cell biding to recombinant spider silk matrices. Biomaterials 74:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren S, Wang J, Chen TL, Li HY, Wan YS, Peng NF, Gui XE, Zhu Y. 2016. Hepatitis B virus stimulated fibronectin facilitates viral maintenance and replication through two distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 11:e0152721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beer C, Pedersen L. 2007. Matrix fibronectin binds gammaretrovirus and assists in entry: new light on viral infections. J Virol 81:8247–8257. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00312-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Hui L, Wang Y, Wang X. 2012. Effect of fibronectin on HBV infection in primary human fetal hepatocytes in vitro. Mol Med Rep 6:1145–1149. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S. 2009. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nm.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li M, Kong XP, Liu H, Cheng LX, Huang JL, Quan L, Wu FY, Hao B, Liu C, Luo B. 2015. Expression of EV71-VP1, PSGL-1 and SCARB2 in tissues of infants with brain stem encephalitis. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi 31:97–101, 104 (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamayoshi S, Ohka S, Fujii K, Koike S. 2013. Functional comparison of SCARB2 and PSGL1 as receptors for enterovirus 71. J Virol 87:3335–3347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02070-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim H, Yoon CS, Kim H, Rah B. 1999. Expression of extracellular matrix components fibronectin and laminin in the human fetal heart. Cell Struct Funct 24:19–26. doi: 10.1247/csf.24.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coolen NA, Schouten KC, Middelkoop E, Ulrich MM. 2010. Comparison between human fetal and adult skin. Arch Dermatol Res 302:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0989-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo Z, Dong X, Li Y, Zhang Q, Kim C, Song Y, Kang L, Liu Y, Wu K, Wu J. 2014. PolyC-binding protein 1 interacts with 5′-untranslated region of enterovirus 71 RNA in membrane-associated complex to facilitate viral replication. PLoS One 9:e87491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su PY, Liu YT, Chang HY, Huang SW, Wang YF, Yu CK, Wang JR, Chang CF. 2012. Cell surface sialylation affects binding of enterovirus 71 to rhabdomyosarcoma and neuroblastoma cells. BMC Microbiol 12:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]