ABSTRACT

The human tumor viruses that replicate as plasmids (we use the term plasmid to avoid any confusion in the term episome, which was coined to mean DNA elements that occur both extrachromosomally and as integrated forms during their life cycles, as does phage lambda) share many features in their DNA synthesis. We know less about their mechanisms of maintenance in proliferating cells, but these mechanisms must underlie their partitioning to daughter cells. One amazing implication of how these viruses are thought to maintain themselves is that while host chromosomes commit themselves to partitioning in mitosis, these tumor viruses would commit themselves to partitioning before mitosis and probably in S phase shortly after their synthesis.

KEYWORDS: human tumor viruses, partitioning, synthesis

INTRODUCTION

Tumorigenic human papillomaviruses (HPVs), tumorigenic Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) all encode cis-acting origins of DNA synthesis and cis-acting elements that likely support chromosomal tethering. They also encode trans-acting proteins that bind these sites and mediate the initiation of DNA synthesis and the tethering of the viral genomes directly or indirectly to host chromosomes. A molecular understanding of how these tumor viruses maintain themselves during the cell cycle will identify targets to force their elimination and treat their associated cancers.

SYNTHESIS OF VIRAL PLASMID REPLICONS

HPV16, -18, and -31 cause almost all cervical carcinomas and about a quarter of head and neck cancers in people (1, 2). The genomes of these viruses are approximately 8 kbp in length and have one track of cis-acting elements termed variously the long control region or the upstream regulatory region (URR) to which an origin of DNA synthesis has been mapped in the related virus HPV11 (Fig. 1) (3). This site corresponds to that identified earlier in bovine papillomavirus 1 (BPV1) (Fig. 1) (4). Viral proteins E1 and E2 bind within the URR and contribute to viral DNA synthesis; their contributions, however, are complicated by the distinct modes of viral DNA synthesis in different layers of stratified epithelial cells. In basal cells, which divide as do tumor cells, the viral genomes appear to undergo licensed DNA synthesis, as measured in density shift experiments (5) (Fig. 2). When these cells differentiate and cease to divide, the viral DNA is amplified in an unlicensed manner to yield the genomes to be encapsidated in progeny virions (6) (Fig. 2). The E1 protein is a helicase (7) that, while unnecessary to maintain licensed DNA synthesis (8), is necessary for its amplification in differentiating cells (8). The E2 protein is the favored candidate for tethering viral genomes indirectly to chromosomes through protein binding and thus, potentially, to their partitioning. The E2 protein can bind one component of the origin recognition complex (ORC). Licensing of DNA synthesis at an origin requires the prereplication complex, which includes most or all of the ORC to bind that origin (9). It therefore seems likely that the URR of HPVs will be bound by the ORC in basal cells, but no such binding has been detected (10). It thus is unclear whether or how HPV DNA synthesis is regulated in latently infected basal cells.

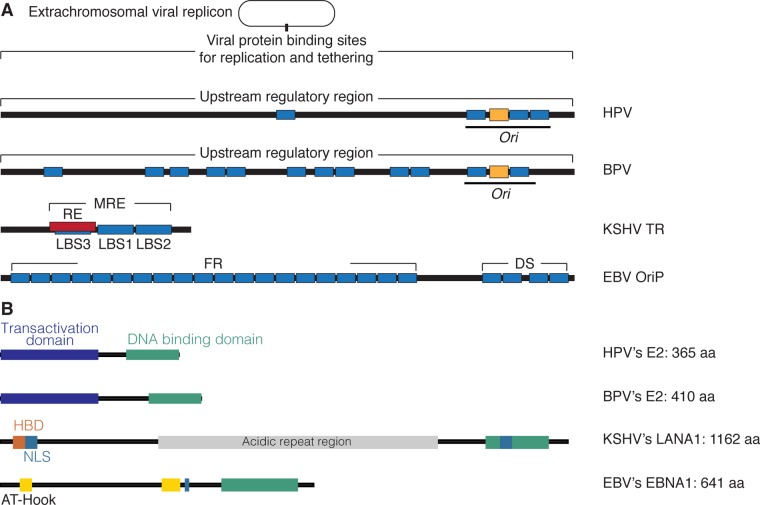

FIG 1.

Diagrams of the DNA elements that mediate DNA synthesis and chromosomal tethering and the viral proteins that bind them. (A) HPV and BPV have multiple binding sites (blue rectangles) for the E2 protein and sites for initiation of DNA (yellow rectangles) associated with them. KSHV has an MRE on each of its 16 to 50 TRs, which consists of an RE (in red) and three LANA1-binding sites (LBS1, LBS2, and LBS3; shown as blue rectangles). The EBV origin of plasmid replication, oriP, has 4 binding sites for the protein EBNA1, forming an element of DS where synthesis initiates, and 20 more sites that are needed for tethering (FR) (blue rectangles). (B) HPV- and BPV-encoded E2 proteins have carboxy-terminal DNA-binding domains (green) and amino-terminal transactivation domains that also potentially contribute to tethering by binding various cellular DNA-binding proteins (dark blue). KSHV-encoded LANA1 and EBV-encoded EBNA1 also have carboxy-terminal DNA-binding domains (green). LANA1 has an amino-terminal histone-binding domain (HBD; orange), an acidic repeat region (gray), and two nuclear localization signals (NLS; light blue). EBNA1 has two nuclear localization signals and two amino-terminal AT-hook domains (yellow), both of which are involved in tethering. aa, amino acids.

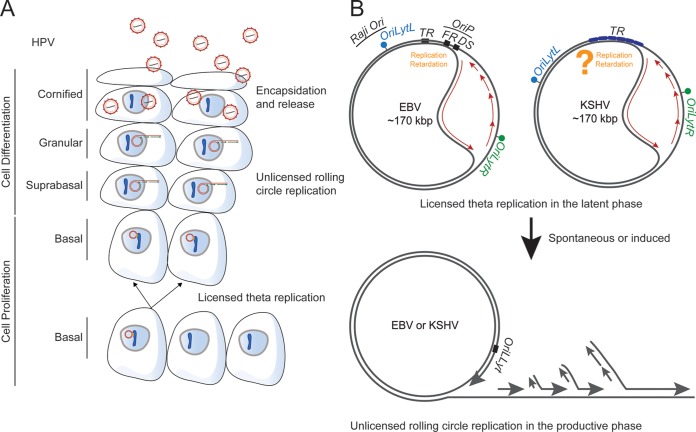

FIG 2.

Replication mechanisms of HPV, KSHV, and EBV plasmids. (A) HPV undergoes licensed DNA synthesis in cervical epithelium basal cells. As cells differentiate to become keratinizing, HPV's genomes are synthesized through unlicensed replication and encapsidated into virus particles. (B) In the latent phases of the EBV and KSHV life cycles, viral genomes are licensed with DNA synthesis initiating at oriP, TRs, and multiple additional loci within the viral genomes (34, 37–39, 43, 44). These multiple additional loci (e.g., Raji ori) function as origins at least for EBV genomes only after they are established in proliferating cells (45). EBNA1 does not bind these sites, indicating that they are unlikely to participate in the partitioning of EBV genomes. DNA synthesis originating in oriP is effectively unidirectional because fork elongation is blocked by EBNA1 binding to the FR element of oriP (34). Studies of KSHV have shown that DNA synthesis initiating from sites other than the TRs is bidirectional (44).

KSHV causes both sarcomas and lymphomas, particularly in immunocompromised patients (1). Like all herpesviruses, KSHV has both a latent and a lytic phase in its life cycle. The transition between these phases is infrequent but can be induced with various treatments in different cells in culture and still is usually inefficient (11). While all herpesviruses are envisioned to synthesize their genomes in the lytic phase via a rolling-circle mechanism, we know that they generate molecules that can be branched and longer than unit length during this phase. KSHV likely uses this mode too (12) (Fig. 2). The viral DNA synthesis in its latent phase has been examined in multiple cell types and found to be licensed with only approximately 90% of the DNA molecules being synthesized in each cell generation (13). This defect has one important implication: because biopsy specimens of KSHV tumors effectively have KSHV genomes in each cell, the virus must be providing these tumors one or more selective advantages to ensure its maintenance in vivo in these proliferating cells (14–16). The origin of DNA synthesis used during KSHV's latent phase has been localized to the viral terminal repeats (TRs) and characterized (17) (Fig. 1). Each TR is 801 bp in length and contains a minimal replication element (MRE) of 71 bp, which consists of a replication element (RE) with a GC-rich sequence and two sites (LBS1 and LBS2) for binding of the KSHV-encoded protein LANA1 (Fig. 1) (18–22). Each TR is occupied by approximately four histone octamers, while the region containing LBS1 and LBS2 is free of nucleosomes (Fig. 1) (23, 24). Binding of LANA1 to viral DNA through its C terminus is required for DNA synthesis (18, 21), and it is consistent with LANA1's structure (25, 26). Recently, a third LANA1-binding site has been identified within the RE region in vitro, although its functions have yet to be elucidated (25). LANA1 forms dimers that each bind to the LBSs to recruit the ORC and initiate the replication of KSHV genomes (23, 27, 28).

Latent KSHV DNA replication requires only the TRs and LANA1 (21, 22, 27, 29). Although only one copy of the TR is sufficient for synthesis of KSHV-derived plasmids (we use the term plasmid to avoid any confusion in the term episome, which was coined to mean DNA elements that occur both extrachromosomally and as integrated forms during their life cycles, as does phage lambda) (27), approximately 16 to 50 copies of it are commonly found in the KSHV genomes analyzed in biopsy specimens (19, 20, 30). Plasmids engineered to have fewer than 16 copies of the TRs accumulate increased numbers of the TRs upon introduction and passaging in cells in culture (31), indicating that an increased number of TRs provides KSHV plasmids a selective advantage in cells. The spacing between the LBSs is also important for KSHV plasmid DNA synthesis (31). The spatial arrangement and the number of binding sites for LANA1 likely contribute to the partitioning of KSHV genomes. LANA1 binds histones H2A and H2B through it amino terminus, which is essential for plasmid tethering and therefore for the partitioning of KSHV genomes (13, 32).

EBV causes a variety of lymphomas and carcinomas in people (1). Viral DNA synthesis during EBV's latent phase initiates in its origin of plasmid DNA synthesis, oriP (33, 34). oriP has two cis-acting elements; one contains a dyad symmetry (DS), and the other is a family of repeats (FR) (Fig. 1). Both of these elements bind the EBV-encoded protein EBNA1 (35, 36). Binding of EBNA1 to the DS element recruits the ORC to support licensed DNA synthesis, which initiates at the DS (Fig. 1) (34, 37–39). This DNA synthesis, like that of KSHV, is imperfect, so that only about 85% of EBV plasmids are synthesized in each cell cycle (40). As with KSHV, cells from biopsy specimens of EBV-positive tumors all harbor viral plasmids, indicating that EBV too must provide tumor cells one or more selective advantages to ensure its maintenance in them. EBNA1 binds both the DS and the 20 copies of EBNA1-binding sites in the FR region through its C terminus (Fig. 1). It binds AT-rich chromosomal DNA directly through its AT-hook domains in its N terminus (41), which likely facilitate not only DNA synthesis but also partitioning of EBV genomes to daughter cells (Fig. 1) (42).

The origins of DNA synthesis within the TR elements of KSHV and oriP of EBV are not the only sites at which DNA synthesis initiates in these viral plasmids during latency. Elegant analyses with pulse-labeling and DNA combing have identified multiple regions in both viral DNAs to which the initiation of DNA synthesis has been mapped (43, 44). It is clear from additional studies with EBV plasmids, though, that these regions cannot support the DNA synthesis needed to establish plasmids newly introduced into cells, nor can they bind EBNA1 (45). Given that EBNA1 is required for partitioning of EBV genomes, the sites other than oriP mapped as origins of DNA synthesis are unlikely to contribute to partitioning.

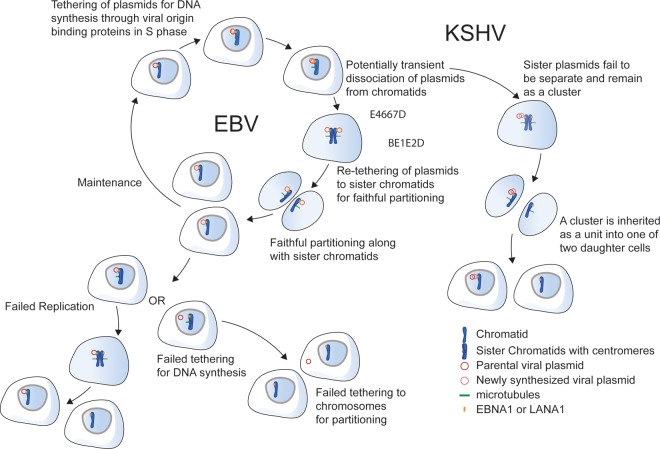

PARTITIONING OF VIRAL PLASMID REPLICONS

By the end of S phase, most of the viral plasmid replicons will have been duplicated. What determines their modes of being distributed or partitioned to daughter cells during mitosis? Each encodes an origin-binding protein that binds site specifically through its carboxy terminus to viral DNA and through its amino terminus to cellular proteins or cellular DNA (Fig. 1). These viral proteins are the favored candidates for tethering of the viral genomes directly or indirectly to host chromosomes. Their tethering, or lack of it, would be instrumental in determining the mode of partitioning and, in turn, if that partitioning is random or quasifaithful. A model that describes plasmid partitioning mediated through tethering includes the following: (i) tethering of plasmids to chromosomes through most of the cell cycle, (ii) dissociation of the plasmids from their origin-binding proteins during S phase when they are displaced by elongating forks and dissociation of the plasmid-protein complexes from chromosomal sites when elongating forks pass through these chromosomal sites, and (iii) retethering sometime after dissociation either to one sister chromatid or to both to mediate partitioning during mitosis (Fig. 3). We will address what is known about each of these tumor viruses that contributes to this simplified model.

FIG 3.

Models of the replication and partitioning of EBV and KSHV plasmids. EBV and KSHV plasmids are tethered to chromosomes via EBNA1 and LANA1, respectively, an essential step for DNA synthesis. The newly synthesized EBV plasmids likely dissociate and retether to sister chromatids for their quasifaithful partitioning to daughter cells. Either failed replication or retethering of plasmids to sister chromatids may lead to the loss of EBV plasmids from the cell population. The newly synthesized KSHV plasmids can cluster together and be inherited as a unit by one of two daughter cells. They may be lost from cells if either replication fails or retethering of plasmids to sister chromatids fails. The details of how HPV and BPV partition remain to be determined.

The E2 protein of HPV16 binds four sites within the URR (46) (Fig. 1). The minimal number of E2-binding sites required for synthesis and maintenance of plasmids derived from HPV18 is three with wild-type spacing (47) or two with optimized spacing (Fig. 1) (48). The latter two studies are particularly important because they indicate that E2 is essential for maintaining the viral plasmids in proliferating cells. It is thought that E2 mediates the maintenance by it amino terminus-binding proteins that can bind host chromosomal DNA or, possibly, mitotic spindles (49, 50). It is not known how HPV might bind mitotic spindles, but both BPV1 E2 and HPV16 E2 do bind the cellular protein ChlR1, a helicase that itself binds the cohesin complex (51, 52). This binding, however, appears not to mediate chromosomal tethering (51). These studies and many others show that the different E2 proteins encoded by the different papillomavirus genomes use their carboxy-terminal DNA-binding domains to bind specifically to their URRs (Fig. 1) (6). They can also bind a variety of targets that may bind host chromosomal sites. The E2 proteins have multiple functions, including promoting the transcription of viral genes; therefore, while inhibiting E2 may lead to loss of the viral genome, the loss cannot necessarily be ascribed to inhibition of chromosomal tethering (Fig. 1) (53). It is also not yet known if HPVs are distributed randomly or nonrandomly to daughter cells. It is even possible if the number of HPV plasmids per cell is sufficiently high, they could be maintained without tethering and would be distributed to daughter cells randomly.

KSHV DNA binds two or three LANA1 dimers to each of its 16 or more TRs in its wild-type plasmid genomes by LANA1's carboxy-terminal DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1). The LANA1 amino termini bind histones H2A and H2B in nucleosomes and thereby tether the genomes to host chromosomes or to additional KSHV genomes (Fig. 1) (13, 32). The binding of KSHV plasmids to additional KSHV plasmids via LANA1's binding both site specifically to TRs and to nucleosomes on the TRs of other KSHV plasmids leads to clusters of genomes binding to chromosomes and partitioning as units, as observed in live-cell imaging (13). These clusters of plasmids are intriguing to contemplate. During S phase, most or all of the members of a cluster must be synthesized, and at the time the replication fork moves through each TR, the two daughter molecules must dissociate from their former binding sites, at least transiently (Fig. 3). Sixteen or more TRs take up 12.8 kbp or more of DNA and would take 5 to 10 min to be synthesized even if the bound LANA1 molecules did not impede fork progression. As the forks progress, yielding daughter molecules that are bound by nucleosomes, the displaced LANA1 molecules presumably rebind and stabilize new, larger clusters that also have been visualized to grow over multiple sequential cell cycles (13). One or more KSHV plasmids in these clusters must be bound to a chromosomal site, as well as to other KSHV plasmids, by the beginning of mitosis to mediate their observed partitioning (Fig. 3). Imaging of cells late in mitosis has shown that KSHV plasmids are associated with chromosomes as they separate to daughter cells, supporting the model in which they are tethered to chromosomes during mitosis (13). The tethering of clusters of KSHV plasmids leads to their partitioning randomly, as opposed to quasifaithfully, as measured by live-cell imaging (13). The clustering of KSHV plasmids requires LANA1's binding of histones H2A and H2B in nucleosomes; substituting LANA1's histone-binding domain with the AT-hook domains of EBNA1 supports the stable synthesis of KSHV plasmids but not their clustering (13). The chimeric LANA1 molecule does not support random partitioning either (13). LANA1 binds multiple cellular proteins, including MeCP2, NuMA, Bub1, CENP-F, and BRD2 and -4 (54–60), which could contribute to the tethering of KSHV plasmids by these cellular proteins binding to chromosomal sites. The finding that replacement of LANA1's histone-binding domain with EBNA1's AT-hook domains no longer yields KSHV's characteristic random partitioning points to a pivotal role for histone binding in LANA1's mechanism of partitioning.

EBV's origin of plasmid replication contains the FR element, which can be bound by ∼20 pairs of dimers of EBNA1 site specifically with the array of bound proteins orienting their amino termini to bind AT-rich chromosomal DNA through their AT-hooks (Fig. 1) (41). This direct tethering has been shown to be required for EBV plasmid maintenance because inhibiting it by treating cells with netropsin, which is a compound that binds the minor groove of AT-rich DNA, induces the gradual loss of EBV genomes from proliferating cells (42). The tethering of genomes to chromosomes appears to be required for DNA synthesis per se (61). Therefore, the loss of EBV plasmids concomitant with the inhibition of tethering is not proof that tethering is required for plasmid maintenance or partitioning (Fig. 3). The detected loss could have resulted from inhibition of DNA synthesis. However, newly synthesized EBV plasmids have been seen to associate with each sister chromatid and separate with them as they separate in anaphase by live-cell imaging (40). The latter observations indicate that EBV genomes are partitioned through their binding sister chromatids, presumably shortly after their being synthesized in S phase. We favor this timing because the newly synthesized pairs of EBV genomes appear as single signals in florescence microscopy until they are resolved as separating, distinct dots in anaphase. This direct tethering to individual sister chromatids leads to a striking, quasifaithful partitioning of EBV plasmids to daughter cells, as observed by live-cell imaging and predicted by computational modeling (40).

PARTITIONING OF VIRAL PLASMID REPLICONS, WHERE NOW?

The replication of plasmids in mammalian nuclei is uncommon. That at least three human tumor viruses do so means that elucidating their replication, including the mechanisms of both their synthesis and their maintenance, is warranted. This understanding will uncover intriguing biology and identify potential routes to eliminate these pathogens from tumor cells and thereby treat these cancers. The detection of single viral DNA molecules either in fixed cells by in situ hybridization or in live cells by tagging them with florescent bound proteins has been particularly informative for understanding the partitioning of large herpesviral plasmids (13, 40). The small size of HPV genomes has made these approaches difficult or even intractable. The development of new, more sensitive methods of detection based on earlier in situ hybridization protocols (62) should allow the enumeration of single HPV plasmids in latently infected cells and thereby advance our understanding of the partitioning of this tumor virus. The application of superresolution microscopy to follow fluorescently tagged KSHV and EBV plasmids from their time of synthesis to their retethering to chromosomal sites should also allow a better understanding of how they commit themselves to partitioning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Quincy Rosemarie, Eric C. Johannsen, and Paul F. Lambert for their insights and suggestions.

This work was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (P01 CA022443); the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA133027 and R01 CA070723); the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST106-2320-B-182-036-MY3); the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-EX107-10623BI); the Chang Gung Medical Research Program (CMRPD1G0511); and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou (BMRPF14). B. Sugden is an American Cancer Society research professor.

We have no competing financial interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambert PF, Sugden B. 2014. Viruses and human cancer, p 154–169. In Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Dorshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE (ed), Abeloff's clinical oncology, 5th ed Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. 2017. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm Accessed 3 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auborn KJ, Little RD, Platt TH, Vaccariello MA, Schildkraut CL. 1994. Replicative intermediates of human papillomavirus type 11 in laryngeal papillomas: site of replication initiation and direction of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:7340–7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldeck W, Rosl F, Zentgraf H. 1984. Origin of replication in episomal bovine papilloma virus type 1 DNA isolated from transformed cells. EMBO J 3:2173–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann R, Hirt B, Bechtold V, Beard P, Raj K. 2006. Different modes of human papillomavirus DNA replication during maintenance. J Virol 80:4431–4439. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4431-4439.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBride AA. 2013. The papillomavirus E2 proteins. Virology 445:57–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, Mohr I, Fouts E, Lim DA, Nohaile M, Botchan M. 1993. The E1 protein of bovine papilloma virus 1 is an ATP-dependent DNA helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:5086–5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egawa N, Nakahara T, Ohno S, Narisawa-Saito M, Yugawa T, Fujita M, Yamato K, Natori Y, Kiyono T. 2012. The E1 protein of human papillomavirus type 16 is dispensable for maintenance replication of the viral genome. J Virol 86:3276–3283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06450-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell SP. 2017. Rethinking origin licensing. Elife 6:e24052. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSmet M, Kanginakudru S, Rietz A, Wu WH, Roden R, Androphy EJ. 2016. The replicative consequences of papillomavirus E2 protein binding to the origin replication factor ORC2. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005934. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukac MD, Yuan Y. 2007. Reactivation and lytic replication of KSHV, p 434–460. In Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E (ed), Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aneja KK, Yuan Y. 2017. Reactivation and lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: an update. Front Microbiol 8:613. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu YF, Sugden AU, Fox K, Hayes M, Sugden B. 2017. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stably clusters its genomes across generations to maintain itself extrachromosomally. J Cell Biol 216:2745–2758. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201702013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballestas ME, Chatis PA, Kaye KM. 1999. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science 284:641–644. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesarman E, Moore PS, Rao PH, Inghirami G, Knowles DM, Chang Y. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708–2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decker LL, Shankar P, Khan G, Freeman RB, Dezube BJ, Lieberman J, Thorley-Lawson DA. 1996. The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is present as an intact latent genome in KS tissue but replicates in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of KS patients. J Exp Med 184:283–288. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J Virol 75:3250–3258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3250-3258.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garber AC, Shu MA, Hu J, Renne R. 2001. DNA binding and modulation of gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 75:7882–7892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7882-7892.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagunoff M, Ganem D. 1997. The structure and coding organization of the genomic termini of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Virology 236:147–154. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judde JG, Lacoste V, Briere J, Kassa-Kelembho E, Clyti E, Couppie P, Buchrieser C, Tulliez M, Morvan J, Gessain A. 2000. Monoclonality or oligoclonality of human herpesvirus 8 terminal repeat sequences in Kaposi's sarcoma and other diseases. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:729–736. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu J, Renne R. 2005. Characterization of the minimal replicator of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent origin. J Virol 79:2637–2642. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2637-2642.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim ST, Rubin N, Said J, Levine AM. 2005. Primary effusion lymphoma: successful treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy and rituximab. Ann Hematol 84:551–552. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stedman W, Deng Z, Lu F, Lieberman PM. 2004. ORC, MCM, and histone hyperacetylation at the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent replication origin. J Virol 78:12566–12575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12566-12575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garber AC, Hu J, Renne R. 2002. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) cooperatively binds to two sites within the terminal repeat, and both sites contribute to the ability of LANA to suppress transcription and to facilitate DNA replication. J Biol Chem 277:27401–27411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellert J, Weidner-Glunde M, Krausze J, Lunsdorf H, Ritter C, Schulz TF, Luhrs T. 2015. The 3D structure of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus LANA C-terminal domain bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:6694–6699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421804112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellert J, Weidner-Glunde M, Krausze J, Richter U, Adler H, Fedorov R, Pietrek M, Ruckert J, Ritter C, Schulz TF, Luhrs T. 2013. A structural basis for BRD2/4-mediated host chromatin interaction and oligomer assembly of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and murine gammaherpesvirus LANA proteins. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003640. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim C, Sohn H, Lee D, Gwack Y, Choe J. 2002. Functional dissection of latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus involved in latent DNA replication and transcription of terminal repeats of the viral genome. J Virol 76:10320–10331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10320-10331.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verma SC, Choudhuri T, Kaul R, Robertson ES. 2006. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with origin recognition complexes at the LANA binding sequence within the terminal repeats. J Virol 80:2243–2256. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2243-2256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Garber AC, Renne R. 2002. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus supports latent DNA replication in dividing cells. J Virol 76:11677–11687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11677-11687.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cesarman E, Nador RG, Bai F, Bohenzky RA, Russo JJ, Moore PS, Chang Y, Knowles DM. 1996. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi's sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J Virol 70:8218–8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrestha P, Sugden B. 2014. Identification of properties of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent origin of replication that are essential for the efficient establishment and maintenance of intact plasmids. J Virol 88:8490–8503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00742-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Joukov V, Walter JC, Luger K, Kaye KM. 2006. The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus LANA. Science 311:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1120541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yates J, Warren N, Reisman D, Sugden B. 1984. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:3806–3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gahn TA, Schildkraut CL. 1989. The Epstein-Barr virus origin of plasmid replication, oriP, contains both the initiation and termination sites of DNA replication. Cell 58:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawlins DR, Milman G, Hayward SD, Hayward GS. 1985. Sequence-specific DNA binding of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA-1) to clustered sites in the plasmid maintenance region. Cell 42:859–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90282-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yates JL, Warren N, Sugden B. 1985. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 313:812–815. doi: 10.1038/313812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhuri B, Xu H, Todorov I, Dutta A, Yates JL. 2001. Human DNA replication initiation factors, ORC and MCM, associate with oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:10085–10089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181347998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhar SK, Yoshida K, Machida Y, Khaira P, Chaudhuri B, Wohlschlegel JA, Leffak M, Yates J, Dutta A. 2001. Replication from oriP of Epstein-Barr virus requires human ORC and is inhibited by geminin. Cell 106:287–296. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schepers A, Ritzi M, Bousset K, Kremmer E, Yates JL, Harwood J, Diffley JF, Hammerschmidt W. 2001. Human origin recognition complex binds to the region of the latent origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J 20:4588–4602. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanbo A, Sugden A, Sugden B. 2007. The coupling of synthesis and partitioning of EBV's plasmid replicon is revealed in live cells. EMBO J 26:4252–4262. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sears J, Ujihara M, Wong S, Ott C, Middeldorp J, Aiyar A. 2004. The amino terminus of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1 contains AT hooks that facilitate the replication and partitioning of latent EBV genomes by tethering them to cellular chromosomes. J Virol 78:11487–11505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11487-11505.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakravorty A, Sugden B. 2015. The AT-hook DNA binding ability of the Epstein Barr virus EBNA1 protein is necessary for the maintenance of viral genomes in latently infected cells. Virology 484:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norio P, Schildkraut CL. 2001. Visualization of DNA replication on individual Epstein-Barr virus episomes. Science 294:2361–2364. doi: 10.1126/science.1064603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verma SC, Lu J, Cai Q, Kosiyatrakul S, McDowell ME, Schildkraut CL, Robertson ES. 2011. Single molecule analysis of replicated DNA reveals the usage of multiple KSHV genome regions for latent replication. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002365. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CY, Sugden B. 2008. Identifying a property of origins of DNA synthesis required to support plasmids stably in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:9639–9644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801378105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hegde RS, Androphy EJ. 1998. Crystal structure of the E2 DNA-binding domain from human papillomavirus type 16: implications for its DNA binding-site selection mechanism. J Mol Biol 284:1479–1489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Doorslaer K, Chen D, Chapman S, Khan J, McBride AA. 2017. Persistence of an oncogenic papillomavirus genome requires cis elements from the viral transcriptional enhancer. mBio 8:e01758-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01758-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ustav M Jr, Castaneda FR, Reinson T, Mannik A, Ustav M. 2015. Human papillomavirus type 18 cis-elements crucial for segregation and latency. PLoS One 10:e0135770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakakibara N, Chen D, Jang MK, Kang DW, Luecke HF, Wu SY, Chiang CM, McBride AA. 2013. Brd4 is displaced from HPV replication factories as they expand and amplify viral DNA. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003777. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Tine BA, Dao LD, Wu SY, Sonbuchner TM, Lin BY, Zou N, Chiang CM, Broker TR, Chow LT. 2004. Human papillomavirus (HPV) origin-binding protein associates with mitotic spindles to enable viral DNA partitioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:4030–4035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306848101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris L, McFarlane-Majeed L, Campos-Leon K, Roberts S, Parish JL. 2017. The cellular DNA helicase ChlR1 regulates chromatin and nuclear matrix attachment of the human papillomavirus 16 E2 protein and high-copy-number viral genome establishment. J Virol 91:e01853-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parish JL, Bean AM, Park RB, Androphy EJ. 2006. ChlR1 is required for loading papillomavirus E2 onto mitotic chromosomes and viral genome maintenance. Mol Cell 24:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McPhillips MG, Oliveira JG, Spindler JE, Mitra R, McBride AA. 2006. Brd4 is required for E2-mediated transcriptional activation but not genome partitioning of all papillomaviruses. J Virol 80:9530–9543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01105-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krithivas A, Fujimuro M, Weidner M, Young DB, Hayward SD. 2002. Protein interactions targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to cell chromosomes. J Virol 76:11596–11604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11596-11604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim C, Lee D, Seo T, Choi C, Choe J. 2003. Latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus functionally interacts with heterochromatin protein 1. J Biol Chem 278:7397–7405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumura S, Persson LM, Wong L, Wilson AC. 2010. The latency-associated nuclear antigen interacts with MeCP2 and nucleosomes through separate domains. J Virol 84:2318–2330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01097-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ottinger M, Christalla T, Nathan K, Brinkmann MM, Viejo-Borbolla A, Schulz TF. 2006. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA-1 interacts with the short variant of BRD4 and releases cells from a BRD4- and BRD2/RING3-induced G1 cell cycle arrest. J Virol 80:10772–10786. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00804-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Platt GM, Simpson GR, Mittnacht S, Schulz TF. 1999. Latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with RING3, a homolog of the Drosophila female sterile homeotic (fsh) gene. J Virol 73:9789–9795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Viejo-Borbolla A, Ottinger M, Bruning E, Burger A, Konig R, Kati E, Sheldon JA, Schulz TF. 2005. Brd2/RING3 interacts with a chromatin-binding domain in the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 (LANA-1) that is required for multiple functions of LANA-1. J Virol 79:13618–13629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13618-13629.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao B, Verma SC, Cai Q, Kaul R, Lu J, Saha A, Robertson ES. 2010. Bub1 and CENP-F can contribute to Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome persistence by targeting LANA to kinetochores. J Virol 84:9718–9732. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00713-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodin TL, Najrana T, Yates JL. 2013. Efficient replication of Epstein-Barr virus-derived plasmids requires tethering by EBNA1 to host chromosomes. J Virol 87:13020–13028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01606-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Player AN, Shen LP, Kenny D, Antao VP, Kolberg JA. 2001. Single-copy gene detection using branched DNA (bDNA) in situ hybridization. J Histochem Cytochem 49:603–612. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]