Abstract

storage is the most prevalent method for graft preservation in kidney transplantation (KTX). The protective effects of various preservation solutions have been studied extensively in both clinical trials and experimental animal models. However, a paucity of studies have examined the effect of different preservation solutions on graft function in mouse KTX; in addition, the tolerance of the transplanted grafts to further insult has not been evaluated, which was the objective of the present study. We performed mouse KTX in three groups, with the donor kidneys preserved in different solutions for 60 min: saline, mouse serum, and University of Wisconsin (UW) solution. The graft functions were assessed by kidney injury markers and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The grafts that were preserved in UW solution exhibited better functions, reflected by 50 and 70% lower plasma creatinine levels as well as 30 and 55% higher plasma creatinine levels in GFR than serum and saline groups, respectively, during the first week after transplants. To examine the graft function in response to additional insult, we induced ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) by clamping the renal pedicle for 18 min at 4 wk after KTX. We found that the grafts preserved in UW solution exhibited ~30 and 20% less injury assessed by kidney injury markers and histology than in other two preservation solutions. Taken together, our results demonstrated that UW solution exhibited a better protective effect in transplanted renal grafts in mice. UW solution is recommended for use in mouse KTX for reducing confounding factors such as IRI during surgery.

Keywords: ischemia reperfusion injury tolerance, mouse kidney transplantation, preservation solution

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation (KTX) remains the best treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease. Organ preservation has been considered “the supply line for organ transplantation” (23). Good organ preservation is one of the major determinants of graft outcomes after renal revascularization (8). Static cold storage is the most prevalent method for preservation of renal grafts for transplantation (14, 17). The protective effects of various preservation solutions have been studied extensively in both clinical trials (11, 15) and several experimental animal models (5, 12, 21). However, few studies compared the preservation solutions in mouse KTX.

The significance of KTX in murine has been widely recognized, especially in the investigation of the immune response of the transplanted grafts (6, 7, 16). One of the advantages for using murine in research is the availability of genetically modified mouse lines and technologies for genetic engineering (4, 26). In addition, cross-transplantation between global knockout and wild-type mice producing kidney-specific knockout models is a useful strategy for determination of the significance of a target gene in the kidney (2, 3).

However, KTX in mice is challenging, with a variable success rate between 40 and 70% (16). Because of the technical complexity and high mortality rates, only a handful of research centers perform KTX in mice. In addition, there is a paucity of research on the protective effect of preservation solutions on graft functions after KTX and in response to additional insult in mice.

In the present study, we compared saline, University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, and mouse serum in the protection of the graft functions after mouse KTX by measurement of the injury markers and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). To determine the response of the graft function to additional insult, we induced ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) by clamping the renal pedicle at 4 wk after transplants. Renal injury was assessed by kidney injury markers and histology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida College of Medicine. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated.

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice aged 10–12 wk (22–25g) were obtained from a vendor (The Jackson Laboratory, Indianapolis, IN). After arrival, the mice were allowed to acclimate in a temperature-controlled environment with 12:12-h light-dark cycle for 1 wk and ad libitum access to mouse chow and tap water. The animals were randomly divided into five groups, sham operation, control (unilateral nephrectomy of the right kidney), saline, UW, and mouse serum groups, based on different storage solutions.

Kidney transplantation and renal function evaluation.

kidney transplantation.

KTX was performed in five steps, donor preparation, recipient preparation, kidney implantation, ureteral implantation, and nephrectomy of the native kidney, as we recently described with slight modifications (29). Briefly, during the donor nephrectomy, the aorta below the right renal artery, the distal aorta, and the inferior vena cava (IVC) were isolated and cross-clamped, and the left renal vein was transected at the vena cava. One milliliter of heparinized cold solution (4°C) was perfused through the distal aorta with a slightly bended 30-gauge needle connecting to a syringe. The donor kidneys and associated vessels were stored in saline, UW solution, or mouse serum at 4°C for 60 min before transplants. For the recipient preparation, the left kidney of the recipient was nephrectomized. A section of aorta and IVC was cross-clamped and cut longitudinally with an elliptical patch of ∼1.5 mm. The donor’s kidney was transferred from the ice into the right flank of the recipient mouse. The vessel anastomosis was performed in an end-to-side manner between the donor and recipient with 10-0 Ethilon sutures by a knotless technique. The ureteral implantation was accomplished by fixing to the exterior wall of the bladder dome using a 10-0 Ethilon suture. The end of the ureter was cut on the bias to ensure a wider opening. The bladder wall was closed via “figure of eight” stitches using a 10-0 Ethilon suture.

measurements of kidney injury markers.

Plasma creatinine (Pcr) concentrations were measured at 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 days after KTX. Blood (10 µl) was collected into a heparinized microcapillary tube from the tail vein and was immediately centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Plasma (5 µl) was collected and stored in a −80°C freezer until analysis. Pcr levels were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry at the O’Brien Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and were expressed as milligrams per deciliter.

Plasma kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) levels were measured using ELISA kits (R & D Systems, mouse KIM-1 and NGAL Quantikine ELISA Kits) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

gfr measurement.

GFR was measured in conscious mice at 7, 14, and 28 days after KTX with a single bolus intravenous injection of fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)-sinistrin, as we described recently with slight modifications (30). The FITC-sinistrin solution (4 μl/g body wt) was injected via retro-orbital sinus of the mice [penile vein was used previously (30)] under light anesthesia with isoflurane. A small tail nick was performed, and blood was collected (≈5 μl/each) into a heparinized microcapillary tube at 3, 7, 10, 15, 35, 55, 75, and 90 min after injection. The blood samples were centrifuged, and plasma (2 μl/each) was collected. FITC-sinistrin fluorescent intensities of the plasma samples were measured using a plate reader (Cytation5; BioTek). GFR was calculated using a two-compartment model of two-phase exponential decay (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA) (25) and presented as microliters per minute.

Ischemia-reperfusion induced acute kidney injury at 4 wk after KTX.

iri induction.

Four weeks after KTX, IRI was performed as we described previously (28). Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg ip), and body temperature was monitored with a rectal probe and controlled in the range of 36.8–37.0°C. A midventral abdominal incision was performed to expose the kidney. The renal pedicle was isolated and clamped for 18 min. The clamp was then released to allow kidney reperfusion. A Vicryl suture was used to close the incision. The animals were returned to the cage and kept on a heating pad until they gained full consciousness.

measurements of kidney injury markers.

Pcr, KIM-1, and NGAL concentrations were measured 24 h after IRI, as described above.

histology.

Histology of the kidney grafts was examined 24 h after IRI. Kidneys were removed and dissected in the longitudinal axis. Kidney samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for ≥24 h and then embedded in paraffin, cut into 3-µm sections, and stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Kidney injury was evaluated based on percentage of necrotic tubules as reported (19). Ten randomly chosen fields were captured under ×200 magnifications, and the percentage of necrotic tubules in each image was quantified. All morphometric analyses were performed by an experienced renal pathologist (L. Fu) blinded to the experimental procedures.

renal clearance in response to acute volume expansion.

Renal clearance function in response to acute volume expansion (AVE) was carried out in the rest of the mice in each group 2 wk following IRI, as we described previously (30). The mice were anesthetized with ketamine (30 μg/g) and inactin (50 μg/g). Two catheters were placed in the femoral artery for the measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and in the femoral vein for an intravenous infusion of 2% BSA and FITC-sinistrin (2 mg/ml) in a 0.9% NaCl solution at a rate of 0.5 ml/h. A third catheter was inserted into the ureter for the collection of urine. After surgery, urine and plasma were collected during a 30-min period after a 30-min equilibration period. Then, saline was infused (3% body weight) in a bolus, followed by the infusion of FITC-sinistrin at 0.5 ml/h. Urine and plasma were collected during a 60-min period and a 60- to 90-min period after volume expansion. The concentrations of Na+ and sinistrin in the urine and plasma sample were measured. The GFR was calculated from urine sinistrin and plasma sinistrin concentration and urine flow.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. Renal injury evaluation after KTX and AVE between groups was compared using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests as appropriate. The recovery curves post-KTX within animals were compared using Student’s t-test. The kidney injury markers post-IRI were compared among multiple groups using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism, version 6.0h (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

KTX and Renal Function Evaluation

Renal injury and recovery assessment following KTX.

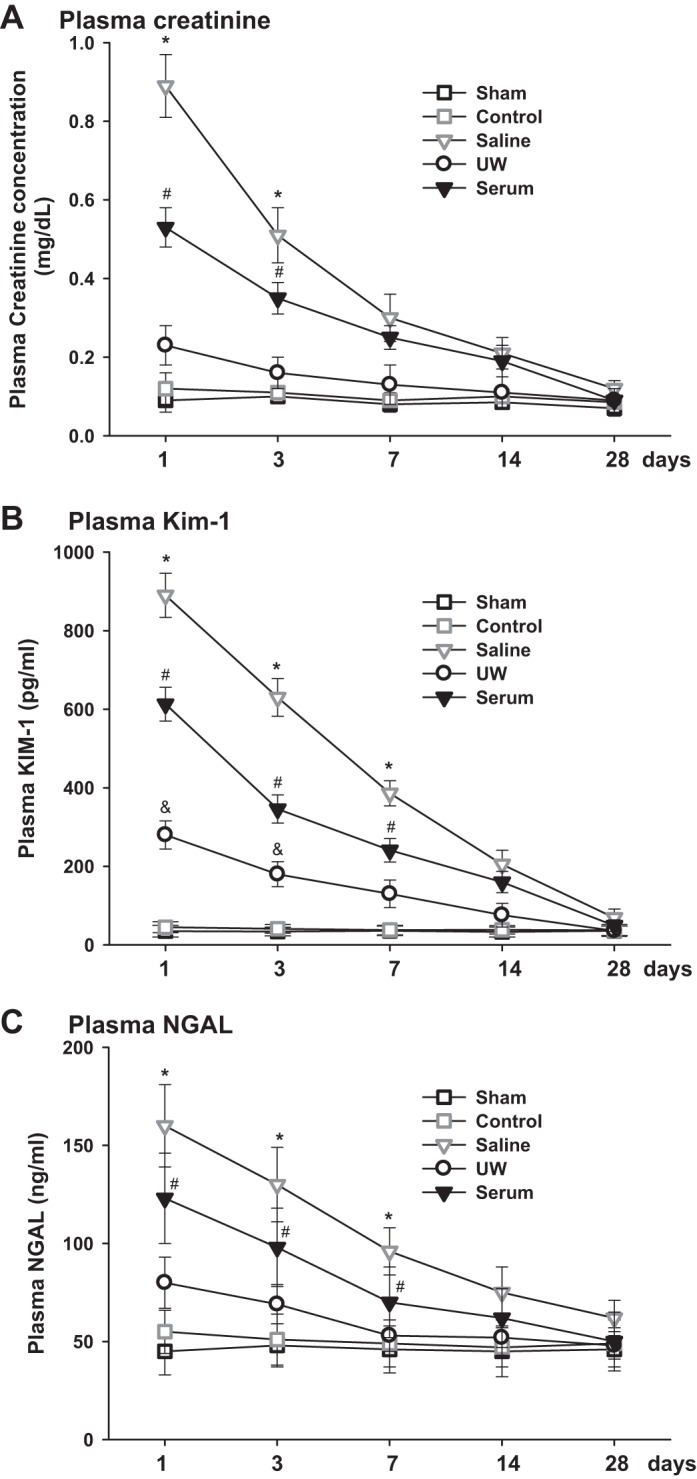

Pcr, KIM-1, and NGAL levels were measured at 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 days following KTX in the five groups of animals. Animals in sham and control groups showed normal levels of Pcr, KIM-1, and NGAL during the observation period. The Pcr, KIM-1, and NGAL levels were significantly increased in other three groups of animals at 24 h post-KTX, and all returned to basal values at 28 days post KTX (P < 0.01 saline, UW, and serum vs. sham and control; n = 10; Fig. 1, A–C).

Fig. 1.

Kidney injury marker measurements following kidney transplantation (KTX). Plasma creatinine (Pcr; A), plasma kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1; B), and plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL; C) were measured over time after KTX (*P < 0.01 vs. other groups, #P < 0.05 vs. UW, sham and control, &P < 0.05 vs. sham and control; n = 10).

Recipients in UW group exhibited very mild renal injury with the lowest Pcr value, which was 0.24 ± 0.06 mg/dl at 24 h after KTX, and the animals recovered quickly to baseline within 7 days after KTX. Recipients in saline group were measured with the highest level of Pcr, which was 0.86 ± 0.08 mg/dl at 24 h after KTX and was still 1.5-fold higher than baseline 7 days after KTX. The Pcr level in serum group was lower than that in saline group but significantly higher than that in the UW group. Plasma KIM-1 and NGAL showed patterns similar to Pcr in all groups of animals. The levels of KIM-1 and NGAL were lowest in the UW group and highest in the saline group. (P < 0.01, UW vs. serum and saline; P < 0.05, serum vs. saline; n = 10; Fig. 1, A–C).

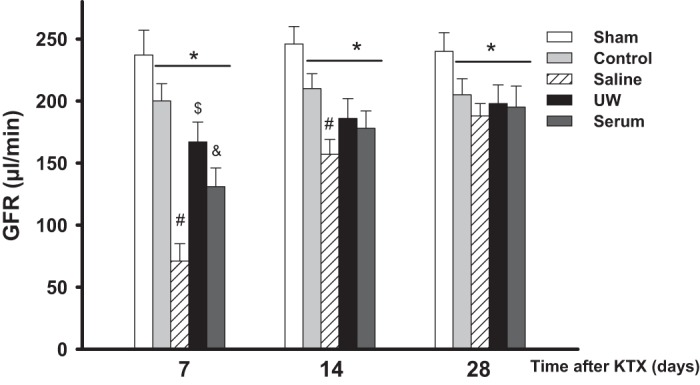

GFR in conscious mice.

GFR was measured in conscious mice at 7, 14, and 28 days after KTX. Sham operation did not affect renal function reflected by normal GFR values. The GFR in the control group was in the normal range and consistent during the observed period of time, which was ∼83% of the sham group. The GFR levels in the UW, saline, and serum groups were significantly lower than the sham and control groups 7 and 14 days post-KTX and returned to a similar level as the control group 28 days post- KTX (P < 0.01, saline, UW, and serum vs. sham and control at 7 and 14 days; n = 10; Fig. 2). The mice in the UW group exhibited the highest GFR 7 and 14 days after KTX, followed by the serum and saline groups. The GFR of the UW group was 167 ± 16 µl/min 7 days after KTX, which was ∼23 and 50% higher than that of serum and saline groups, respectively. The GFR increased gradually to a similar level at 28 days after KTX for all animals in the three groups. (P < 0.01, UW vs. serum and saline at 7 and 14 days; P < 0.05, serum vs. saline at 7 days; n = 10; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) measurement. GFR was measured in conscious mice following KTX (*P < 0.01 vs. sham, #P < 0.01 vs. other groups, $P < 0.01 vs. control and serum, &P < 0.01 vs. saline; n = 10).

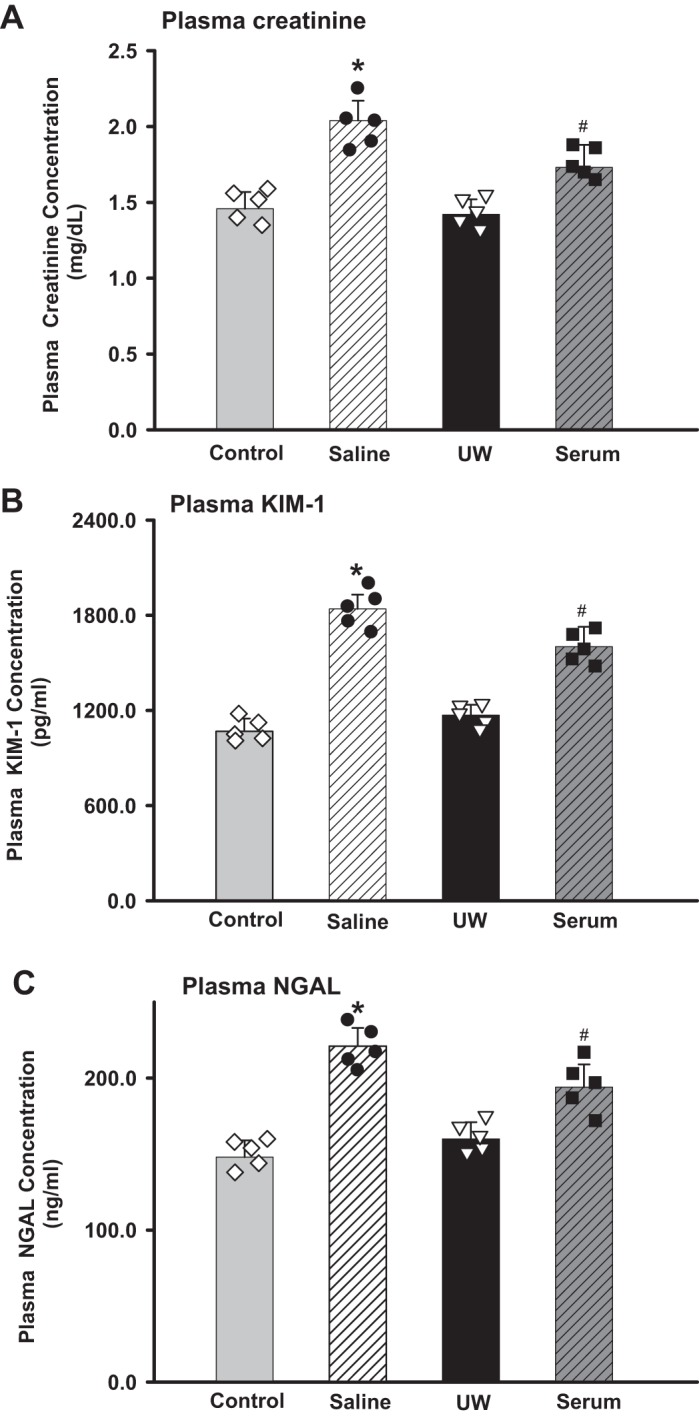

Renal Injury Values 24 h Post-IRI

To test the ischemic tolerance, we performed IRI and measured injury marker levels 24 h later. The Pcr was significantly increased in all groups. The UW and control group showed similar Pcr values. The mice in the saline group showed the highest level of Pcr (2.04 ± 0.17 mg/dl), followed by the serum group (1.77 ± 0.19 mg/dl), UW group (1.43 ± 0.14 mg/dl), and control group. The plasma KIM-1 and NGAL were in similar patterns as the Pcr. (P < 0.01, saline vs. other groups; P < 0.05, UW vs. serum; n = 5; Fig. 3, A–C).

Fig. 3.

Kidney injury marker measurements at 24 h postischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). Pcr (A), plasma kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) (B), and plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) (C) were measured and compared among saline, University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, and serum groups 24 h postischemia reperfusion (*P < 0.01 vs. UW and control, #P < 0.05 vs. UW; n = 5). Diamond, black dot, triangle and square showed each individual data point for control, saline, UW and serum groups, respectively.

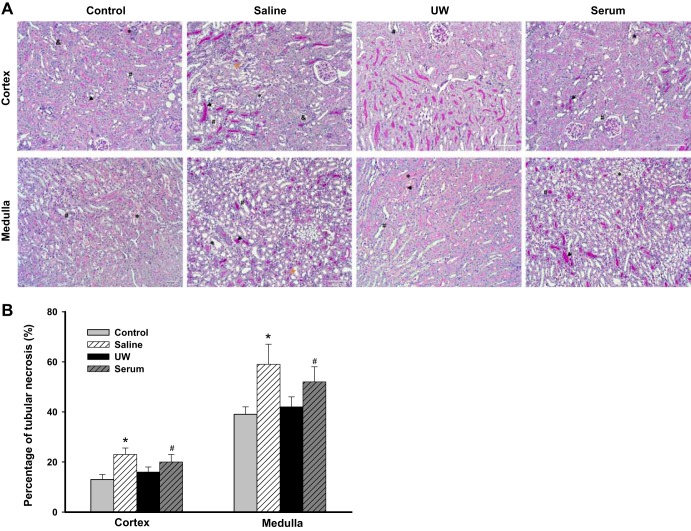

Histology.

Figure 4A shows the representative histology images with PAS staining. Acute tubular injury, including dilatation of the tubular lumina, loss of brush borders, nuclear dropout, sloughing of epithelial cells, focal epithelial cell necrosis, and cast formation, was found in all four groups of mice. The saline group exhibited the most severe tubular injury, with an injury score of 59.6 ± 6.7%, followed by serum group, UW group, and control group, with injury scores of 51.3 ± 5.6, 43.2 ± 4.8, and 41.3 ± 3.2%, respectively. (P < 0.01, saline vs. UW and control; P < 0.05, serum vs. UW and control; n = 5; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A: representative periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-stained histology images. Acute tubular injury, including dilatation of the tubular lumen with loss of brush borders (#), nuclear dropout (yellow arrow), sloughing of epithelial cells with intratubular cell debris (&), focal epithelial cell necrosis (*), and cast formation (black arrow), was found in all 4 groups of mice. B: kidney injury scores. Based on %necrotic tubules, the saline group exhibited the most severe tubular injury, followed by the serum, University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, and control groups. (*P < 0.01 vs. UW and control, #P < 0.05 vs. UW; n = 5).

Kidney clearance function in response to AVE.

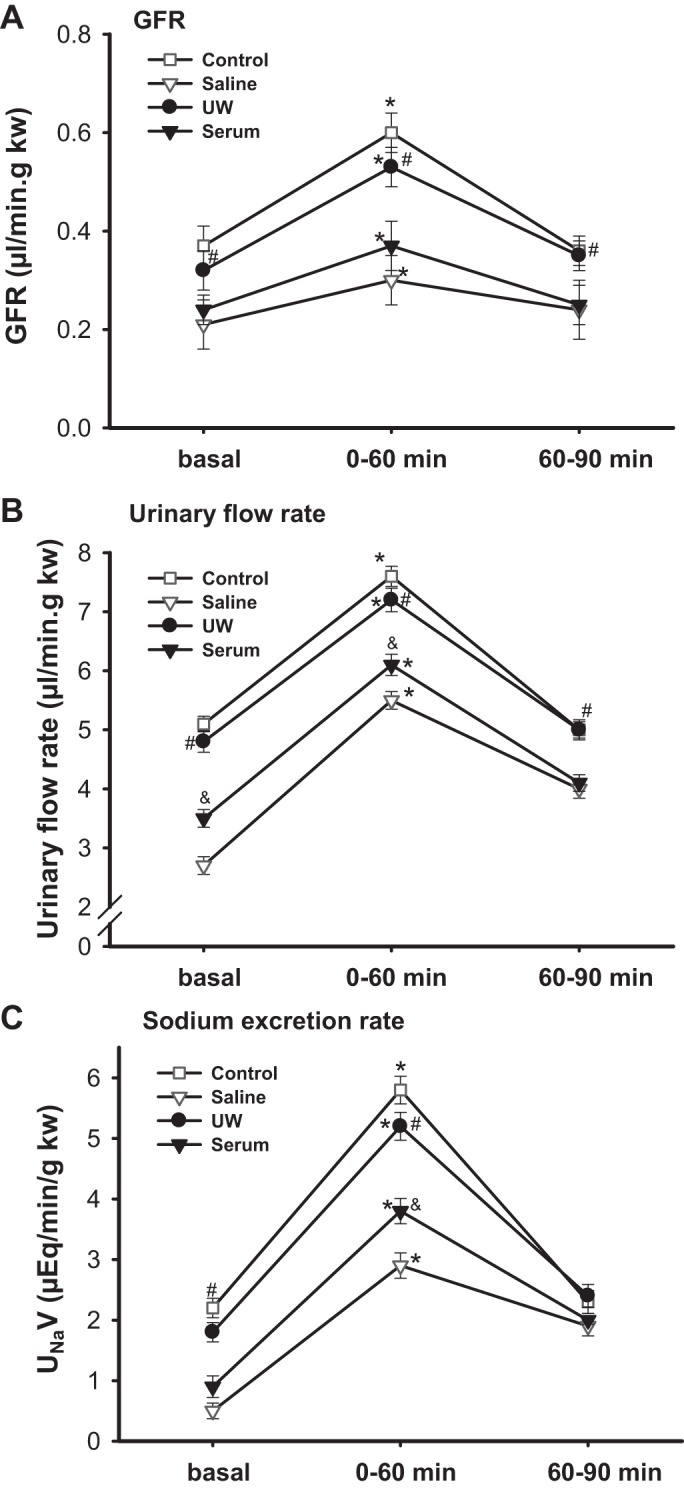

To evaluate the renal hemodynamics and sodium excretion, we measured kidney clearance function in response to AVE 2 wk after IRI by intravenous infusion of saline in all groups of mice.

The MAP was constant in all groups of mice before and during AVE. There were no significant differences in MAP among the four groups. The control group and UW group showed similar basal GFR, which was ∼26 and 33% higher than the serum and saline groups, respectively. GFR rose by ∼66, 44, 64, and 51% during the 60 min after AVE for control, saline, UW, and serum, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. basal; n = 5; Fig. 5A). Mice in the UW and control groups showed the highest urinary flow rate and sodium excretion rate, followed by the serum and saline groups (P < 0.05, UW and control vs. saline and serum; n = 5; Fig. 5, A–C).

Fig. 5.

Kidney clearance function measurement. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR; A), urine flow rate (B), and sodium excretion rate (C) were measured in mice after an acute volume expansion by a bolus infusion of saline of 3% body weight. Kidney clearance function was measured from 0 to 60 min and 60 to 90 min after volume expansion (*P < 0.01 vs. basal, #P < 0.05 vs. saline and serum, &P < 0.05 vs. saline; n = 5).

Body weight, kidney weight, and survival rate.

The body weight dropped to ∼15% of the basal value in all groups of animals 3 days after KTX. The mice started to regain body weight 1 wk after KTX. There was no significant difference in the body weight or kidney weight at the end of the experiment in the three groups. (n = 5; Table 1). The survival rate over 4 wk was >90%, and there were no significant differences among the three groups. The mice constantly gained body weight, indicating normal growth and well being.

Table 1.

BW and KW change

| Control | Saline | UW Solution | Serum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW, g | 29.3 ± 0.4 | 28.4 ± 0.5 | 26.8 ± 0.3 | 28.8 ± 0.2 |

| KW, g | 0.2446 ± 0.03 | 0.2393 ± 0.04 | 0.2230 ± 0.03 | 0.2467 ± 0.02 |

Values are means ± SE. BW, body weight; KW, kidney weight; UW, University of Wisconsin. There were no significant differences in the BW or KW at the end of the experiment in the 3 groups (n = 5).

DISCUSSION

We compared the protective effects of saline, UW solution, and mouse serum as preservation solutions on mouse kidney graft function after KTX and the ischemia tolerance of the transplanted grafts to subsequent warm IRI. The renal grafts preserved in UW exhibited best function and ischemia tolerance after KTX, with ∼30 and 20% less renal injury than that preserved in the other two preservation solutions.

Cold storage is able to preserve renal grafts for up to 24 h for KTX. UW solution is one of the widely used preservation solutions in many transplant centers worldwide (1, 5, 24). Saline is extensively used as a storage solution in rodent KTX because it is cheap and of low viscosity compared with the UW solution. Although numerous studies have been carried out in studying the protective effect of these preservation solutions in clinical trials and on large animals, few studies have compared the protective effect of different preservation solutions in mouse KTX. In the present study, we examined the effect of the three preservation solutions, saline, UW solution, and mouse serum, on the graft function and response to IRI after KTX.

Previously, we demonstrated that it only caused mild renal injury when the cold storage time of the grafts was <30 min (22, 29). In the present study, to induce moderate renal injury, we extended the storage time to 60 min. Sixty minutes of cold ischemia plus 25–30 min of warm ischemia during the anastomosis caused moderate kidney injury after transplant with a significant increase of Pcr in all three groups of mice. UW preservation solution exhibited the best protective effect after KTX, followed by serum and saline determined by kidney injury markers (Pcr, KIM-1, and NGAL) and GFR measurement. The UW solution group also showed quicker renal function recovery after KTX compared with the other two groups. The graft functions recovered gradually and reached similar levels in all groups of animals 4 wk after KTX.

The grafts preserved in saline exhibited the worst renal function and slowest functional recovery after KTX. The mechanism may involve the lack of cell impermeant, which causes cell swelling and injury (20). Serum has been used in the preservation solution to reduce the cell swelling problem, as it holds water in the capillary and retards movement into the interstitial space to cause edema (14). The animals in the serum group showed better renal function than the saline group, but it was still significantly worse than the UW group. One of the reasons that UW solution is not widely used in mouse KTX may due to the high viscosity of the solution, which makes the surgical procedures more difficult. In the present study, we compared the different solutions during KTX. We found that the UW solution is stickier, which makes it more challenging in the renal arteries and ureters anastomosis. However, with more practice and by carefully and gently rinsing the opening of the vessel with saline just before anastomosis, there were no difference in transplant operations in the three groups, including the times for vessel anastomosis and ureteral implantation. We did not compare other popular preservation solutions that are used in clinics, such as Collins solution and histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate solution, etc. We believe that they should be similar to the UW solution.

Recipients of KTX often suffer additional insults. Transplanted kidneys are characterized by increased susceptibility to additional insults, such as renal ischemia (9, 18). Therefore, adequate graft functional reserve is crucial for the survival of the transplanted grafts in response to additional injuries. To examine the ischemia tolerance and renal functional reserve of the transplanted kidneys, we performed IRI in the transplanted kidneys 4 wk after KTX. We found that the UW solution showed the best protective effect, whereas saline exhibited the worst protective effect in graft function in response to IRI, although the transplanted kidneys were functionally normal before IRI. Our findings indicated that kidneys that underwent more severe injury will be more vulnerable to further insults. Our results are in agreement with the findings of clinical trials about acute kidney injury (AKI) that patients with previous AKI are more susceptible to additional insults and development of chronic kidney disease (10, 13, 27).

In summary, we compared the protective effect of saline, UW solution, and mouse serum as preservation solutions in mouse KTX and the ischemia tolerance of the kidney grafts to subsequent warm IRI. We found that UW solution exhibited markedly improved organ functional reserve. Therefore, UW solution is recommended for use in mouse KTX as one of the strategies for reducing confounding factors during surgery.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-099276 and DK-098582 (to R. Liu).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.W. and J.W. conceived and designed research; L.W. performed experiments; L.W. analyzed data; L.W., J.W., L.F., and R.L. interpreted results of experiments; L.W. prepared figures; L.W. drafted manuscript; L.W., S.J., H.-H.L., J.Z., and R.L. edited and revised manuscript; L.W. and R.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belzer FO, Sollinger HW, Glass NR, Miller DT, Hoffmann RM, Southard JH. Beneficial effects of adenosine and phosphate in kidney preservation. Transplantation 36: 633–635, 1983. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198336060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman JL, Brennan K, Ngo T, Balaji P, Graham RM, Smith NJ. Rapid knockout and reporter mouse line generation and breeding colony establishment using EUCOMM conditional-ready embryonic stem cells: a case study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 6: 105, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim H-S, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 115: 1092–1099, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI23378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschini N, Cheng O, Zhang X, Ruiz P, Mannon RB. Inhibition of prolyl-4-hydroxylase ameliorates chronic rejection of mouse kidney allografts. Am J Transplant 3: 396–402, 2003. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golriz M, Fonouni H, Kuttymuratov G, Esmaeilzadeh M, Rad MT, Jarahian P, Longerich T, Faridar A, Abbasi S, Mehrabi A, Gebhard MM. Influence of a modified preservation solution in kidney transplantation: a comparative experimental study in a porcine model. Asian J Surg 40: 106–115, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gueler F, Rong S, Gwinner W, Mengel M, Bröcker V, Schön S, Greten TF, Hawlisch H, Polakowski T, Schnatbaum K, Menne J, Haller H, Shushakova N. Complement 5a receptor inhibition improves renal allograft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2302–2312, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gueler F, Rong S, Mengel M, Park JK, Kiyan J, Kirsch T, Dumler I, Haller H, Shushakova N. Renal urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) receptor but not uPA deficiency strongly attenuates ischemia reperfusion injury and acute kidney allograft rejection. J Immunol 181: 1179–1189, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guibert EE, Petrenko AY, Balaban CL, Somov AY, Rodriguez JV, Fuller BJ. Organ preservation: current concepts and new strategies for the next decade. Transfus Med Hemother 38: 125–142, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000327033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariharan S, Peddi VR, Savin VJ, Johnson CP, First MR, Roza AM, Adams MB. Recurrent and de novo renal diseases after renal transplantation: a report from the renal allograft disease registry. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 928–931, 1998. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9631835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 891–898, 2009. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05571008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illouz S, Nakamura T, Webb M, Thava B, Bikchandani J, Robertson G, Lloyd D, Berry D, Wada H, Dennison A. Comparison of University of Wisconsin and ET-Kyoto preservation solutions for the cryopreservation of primary human hepatocytes. Transplant Proc 40: 1706–1709, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson NV, Sundberg R, Lindell S, Southard JH, Belzer FO. A comparison of cold storage solutions for hepatic preservation using the isolated perfused rabbit liver. Cryobiology 25: 300–310, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(88)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen KL, Smith MW, Unruh ML, Siroka AM, O’Connor TZ, Palevsky PM; VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trial Network . Predictors of health utility among 60-day survivors of acute kidney injury in the Veterans Affairs/National Institutes of Health Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1366–1372, 2010. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02570310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CY, Mangino MJ. Preservation methods for kidney and liver. Organogenesis 5: 105–112, 2009. doi: 10.4161/org.5.3.9582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangus RS, Fridell JA, Vianna RM, Milgrom MA, Chestovich P, Chihara RK, Tector AJ. Comparison of histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate solution and University of Wisconsin solution in extended criteria liver donors. Liver Transpl 14: 365–373, 2008. doi: 10.1002/lt.21372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannon RB, Kopp JB, Ruiz P, Griffiths R, Bustos M, Platt JL, Klotman PE, Coffman TM. Chronic rejection of mouse kidney allografts. Kidney Int 55: 1935–1944, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAnulty JF. Hypothermic organ preservation by static storage methods: current status and a view to the future. Cryobiology 60, Suppl: S13–S19, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehrotra A, Rose C, Pannu N, Gill J, Tonelli M, Gill JS. Incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 558–565, 2012. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Siegmund B, Lucia MS, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL. Neutrophil-independent mechanisms of caspase-1- and IL-18-mediated ischemic acute tubular necrosis in mice. J Clin Invest 110: 1083–1091, 2002. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neil DA, Lynch SV, Hardie IR, Effeney DJ. Cold storage preservation and warm ischaemic injury to isolated arterial segments: endothelial cell injury. Am J Transplant 2: 400–409, 2002. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ploeg RJ, Vreugdenhil P, Goossens D, McAnulty JF, Southard JH, Belzer FO. Effect of pharmacologic agents on the function of the hypothermically preserved dog kidney during normothermic reperfusion. Surgery 103: 676–683, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rong S, Lewis AG, Kunter U, Haller H, Gueler F. A knotless technique for kidney transplantation in the mouse. J Transplant 2012: 127215, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/127215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Southard JH, Belzer FO. Organ preservation. Annu Rev Med 46: 235–247, 1995. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Southard JH, van Gulik TM, Ametani MS, Vreugdenhil PK, Lindell SL, Pienaar BL, Belzer FO. Important components of the UW solution. Transplantation 49: 251–257, 1990. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturgeon C, Sam AD II, Law WR. Rapid determination of glomerular filtration rate by single-bolus inulin: a comparison of estimation analyses. J Appl Physiol (1985) 84: 2154–2162, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.6.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandamme TF. Use of rodents as models of human diseases. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 6: 2–9, 2014. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.124301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG; University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group . Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA 302: 1179–1185, 2009. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Song J, Buggs J, Wei J, Wang S, Zhang J, Zhang G, Lu Y, Yip KP, Liu R. A new mouse model of hemorrhagic shock-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F134–F142, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00347.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Song J, Wang S, Buggs J, Chen R, Zhang J, Wang L, Rong S, Li W, Wei J, Liu R. Cross-sex transplantation alters gene expression and enhances inflammatory response in the transplanted kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F326–F338, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00039.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Chandrashekar K, Wang L, Lai EY, Wei J, Zhang G, Wang S, Zhang J, Juncos LA, Liu R. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase 1 induces salt-sensitive hypertension in nitric oxide synthase 1α knockout and wild-type mice. Hypertension 67: 792–799, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.07032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]