Abstract

Both cognitive and motor symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) arise from either too little or too much dopamine (DA). Akinesia stems from DA neuronal cell loss, and dyskinesia often stems from an overdose of DA medication. Cognitive behaviors typically associated with frontal cortical function, such as working memory and task switching, are also affected by too little or too much DA in PD. Whether motor and cognitive circuits overlap in PD is unknown. In this article, we show that whereas motor performance improves in people with PD when on dopaminergic medication compared with off medication, perceptual decision-making based on previously learned information (priors) remains impaired whether on or off medications. To rule out effects of long-term DA treatment and dopaminergic neuronal loss such as occur in PD, we also tested a group of people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia, a disease that involves the basal ganglia, like PD, but has motor symptoms that are insensitive to dopamine treatment and is not thought to involve frontal cortical DA circuits, unlike PD. We found that people with focal dystonia showed intact perceptual decision-making performance but impaired use of priors in perceptual decision-making, similar to people with PD. Together, the results show a dissociation between motor and cognitive performance in people with PD and reveal a novel cognitive impairment, independent of sensory and motor impairment, in people with focal dystonia. The combined results from people with PD and people with focal dystonia provide mechanistic insights into the role of basal ganglia non-dopaminergic circuits in perceptual decision-making based on priors.

Keywords: basal ganglia; bias; cognition; dopa-unresponsive dystonia, dopamine; dystonia; focal dystonia; implicit learning; glass patterns; movement disorders; Parkinson’s disease; perception; priors

INTRODUCTION

The neuronal circuitry underlying cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is unknown but it is mostly considered to involve impaired frontal cortical dopaminergic circuits (de la Fuente-Fernández 2012; Halliday et al. 2014; Owen 2004). This is due largely to the similarities in performance on certain cognitive tasks between people with PD and people with frontal lobe damage. Many cognitive behaviors, including working memory, task switching, and the use of learned positive feedback, are associated with frontal cortical dopamine (DA) circuits, and in PD with impairments resulting from either too little or too much DA. Dopaminergic treatment in PD improves some cognitive deficits but produces others (Cools et al. 2001; Foerde and Shohamy 2011b; Foerde et al. 2013a; Frank et al. 2004; Kehagia et al. 2013; MacDonald et al. 2011; Shohamy et al. 2004, 2006; Vo et al. 2014; Warden et al. 2016; Wolpe et al. 2015). Motor symptoms are also associated with too little or too much DA in PD. The akinesia resulting from DA loss is improved with DA treatment; however, too much DA can result in dyskinesia (Bezard et al. 2001; Fahn et al. 2004; Fox et al. 2001). The similarities between the influence of DA on cognition and movement are striking, but whether this represents similar underlying circuitry causing motor and cognitive impairment in PD is unknown.

We recently discovered a novel cognitive impairment in people with PD, which may shed light on the circuits underlying cognitive impairment in PD more broadly. In our previous work, we found that people with PD showed an impaired ability to integrate previously learned information (priors) with sensory information to inform perceptual decisions (Perugini et al. 2016). This impairment occurred in people with PD while on DA medications, suggesting that either the impairment is caused by DA treatment, as the overdose hypothesis would predict (Cools et al. 2001; Gotham et al. 1988; Rowe et al. 2008; Swainson et al. 2000; Vaillancourt et al. 2013), or that the impairment is independent of dopaminergic tone. In this study, we tested these hypotheses directly. We assessed the use of priors in perceptual decision-making in people with PD in two separate sessions: on and off DA medications. We found that people with PD were impaired at using previously learned information regardless of whether on or off medications, indicating that the impairment is independent of DA tone. To ensure DA tone changed on and off medication, we also measured motor performance using the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), a commonly used scale to assess movement ability in PD (Fahn and Elton 1987). We found that the same people who showed no difference in the decision task on or off DA medication showed significant improvement in motor ability on DA medication compared with off DA medication, indicating a dissociation between cognitive and motor impairment in PD. To ensure that the cognitive impairment found in PD did not result from long-term DA treatment or other aspects related to the degeneration of DA neurons as occurs in PD, we tested a group of people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia, a movement disorder involving the basal ganglia, like PD, but, unlike PD, not associated with DA neuronal cell loss or treatment and not thought to involve frontal cortical impairment (Breakefield et al. 2008; Cloud and Jinnah 2010; Jinnah et al. 2013; Neychev et al. 2011). Surprisingly, we found that people with focal dystonia also showed an impaired ability to use previously learned information to guide perceptual decisions. Importantly, people with dystonia were able to make perceptual decisions with strong sensory information, indicating intact sensory and motor processing. Finally, we found that healthy control participants as well as people with PD and dystonia all used the same win-stay lose-shift learning strategy to perform the task, indicating intact learning mechanisms in PD and dystonia. Taken together, we conclude that the impaired ability to use previously learned information for perceptual decisions is independent of DA tone and is unlikely to involve frontal cortical DA circuits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This work was reviewed, approved, and conducted following the regulations of the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles and of the University of California, San Diego, and only after all participants signed a written consent form.

Participants.

We recruited 17 people with PD and 18 people with focal dystonia (cervical dystonia, n = 11; Meige syndrome, n = 2; laryngeal dystonia, n = 3; writer’s cramp, n = 1; musician’s cramp, n = 1), as well as 12 healthy age- and sex-matched control participants (HC). The data from the HC were used previously and reported in Perugini et al. (2016), and they have been reanalyzed here. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological conditions other than PD or dystonia. We tested for color vision in all participants before the experiment using an online version of the Ishihara color test. We tested all participants for the presence of dementia using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and excluded people scoring lower than 25. We used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess whether the presence of depression-like behaviors correlated with performance in our tasks. We tested people with PD using Part III (the motor assessment) of the UPDRS with the exception of the rigidity and postural stability item, which was assessed by the patients’ verbal reports. We also used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in people with PD to assess whether being off medications correlated with anxiety and performance in the decision task. We assessed motor behavior in people with dystonia using the Fahn-Marsden dystonia scale that measures dystonia symptoms and signs (Burke et al. 1985). It is composed of two parts: a movement scale and a disability scale. The scores reported in Table 1 and in Fig. 4E are a sum of the scores from both parts. People who were unable to discriminate the easiest 100% coherence visual stimulus with accuracy equal to or greater than 85% during practice trials were excluded from further analysis and this report (n = 2 PD excluded from both on and off DA medication sessions, and n = 2 dystonia, one with cervical dystonia and one with laryngeal dystonia). Participants received a compensation of $30.00 for a 2-h session and free parking. People with PD participated in two separate sessions, separated by 1–3 wk. In the “on” session, people were taking their regular medication and verbally reported maximal functionality. The “off” session occurred at least 16 h after participants abstained from dopaminergic medication or at least 24 after they abstained from the slow-release dopaminergic medications, before the experiment (Frank et al. 2007; Foerde et al. 2013a; Shiner et al. 2012). Other non-dopaminergic medications were taken as usual (Table 2). The order of the two sessions was counterbalanced across participants. The demographics of the sample population are shown in Table 1, and a list of their medications is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Group demographics

| HC | PDon | PDoff | Dystonia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (M/F) | 12 (5M/7F) | 15 (6M/9F) | 15 (6M/9F) | 16 (2M/14F) |

| Age, yr | 62.5 (8.1) | 63.67 (7.56) | 63.67 (7.56) | 58.5 (13.09) |

| sMMSE | 29 (1.4) | 29 (0.9) | 29 (0.7) | 29 (0.7) |

| BDI | 2 (2.5) | 7 (4.6) | 7 (6.1) | 8 (7.4) |

| BAI | n.a. | 5.8 (4.1) | 6.5 (4.7) | n.a. |

| UPDRS III (no rigidity) | n.a. | 15 (6.4) | 18 (6.6) | n.a. |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | n.a. | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | n.a. |

| Fahn-Marsden scale | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Movement | 12.15(17.55) | |||

| Disability | 1.87 (1.36) | |||

| Total | 14.09 (18.59) | |||

| Years since onset | n.a. | 4.13 (3.14) | 4.13 (3.14) | 16.10 (13.48) |

Values are means (SD) in healthy control participants (HC), people with Parkinson’s disease while on (PDon) and off (PDoff) medications, and people with dystonia. sMMSE, standardized Mini Mental State Examination; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; UPDRS III: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Part III. We did a linear regression analysis to predict the use of prior in all groups from their BDI scores. The BDI scores were not predictive of the use of priors [F(1,58) = 0.23, P > 0.05]. Another linear regression analysis was done to predict the use of prior in PDon and PDoff from their BAI scores. The BAI scores were not predictive of the use of priors [F(1,29) = 0.001, P > 0.05]. There is a statistical significant difference between the UPDRS scores when patients were off vs. on medications [t(14) = 2.27, P = 0.039, paired t-test; Fig. 3A]. This indicates that dopaminergic medications improved motor symptoms; hence, the dopaminergic manipulation we used was effective. PDon and PDoff are the same group of participants tested twice on 2 separate sessions, on medications and off medications. M, males; F, females; n.a., not applicable.

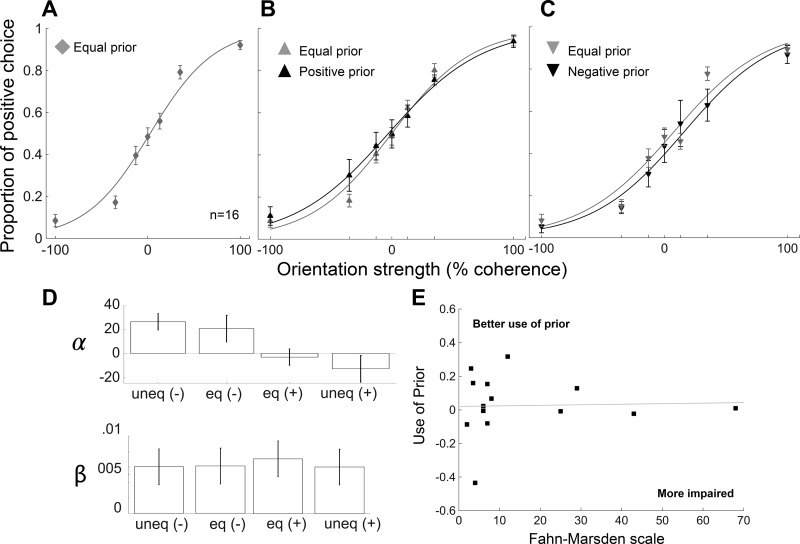

Fig. 4.

People with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia are impaired at using priors to guide perceptual decision-making. A: proportion of positive choices are plotted as a function of orientation strength for a group of 16 people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia (DY; 2 men, 14 women, mean age 61 yr). Data are plotted as in Fig. 1D. People with dystonia are able to perform the task well based on the amount of sensory information provided, and they guess when sensory information is ambiguous. This rules out interpretations based on motor or perceptual impairments. B: comparisons between the equal and unequal prior conditions for participants presented with more frequent positive orientation in the unequal prior trials. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1E. People with dystonia are not able to bias their choices based on prior information. C: same as in B for participants presented with more frequent negative orientation in the unequal prior trials. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1F. Error bars are SE. D: logistic fits, α and β parameters, for dystonia. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1G. E: use of prior for dystonia against the scores on the Fahn-Marsden scale. We excluded one participant with musician’s dystonia from this plot, because the participant had a score of 0 on the Fahn-Marsden (n = 15). There is no correlation between the use of prior and motor impairment in people with dystonia (r = 0.03, P = 0.9).

Table 2.

List of medications

| Medications | HC | PD | Dystonia |

|---|---|---|---|

| l-DOPA* | 12 | ||

| Azilect* | 7 | ||

| DA agonists* | 8 | ||

| Anticholinergics* | 1 | ||

| SSRI/SARI | 1 | 4 | |

| Benzodiazepine | 1 | 8 | |

| Botox or Myobloc | 1 | 5 |

Values are numbers of participants in each group taking each medication. l-DOPA refers to drugs containing levodopa and carbidopa. Azilect is a monoamine oxidase B-inhibitor (MAO-I). Dopamine (DA) agonists include: pramipexole (n = 4), Neupro (n = 1), and ropinerole (n = 3). SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SARI, serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors. All participants were taking levodopa or dopamine agonists or both.

Medications that people with PD did not take during the off session.

Visual stimuli.

We used dynamic, translational Glass pattern stimuli. Glass patterns are made by superimposing two identical dot patterns, one of which is translated in position with respect to the other, giving a strong perception of orientation (Fig. 1A) (Glass 1969). To perceive the orientation, the brain must integrate the local correlations between the dots (or dot pairs) over the whole display. By varying parametrically the percentage of the dot pairs that were correlated (coherence) among 0%, 13%, 35%, and 100%, we obtained different levels of discrimination difficulty. In the stimulus with 100% coherence, all the dot pairs are correlated, so the orientation signal is strong, and therefore the decision is easy. In the 0% coherence stimulus there is no orientation signal, so these trials are impossible and participants guess. The dynamic nature of the stimulus was produced by presenting 30 frames of translational patterns sequentially at a rate of 85 frames/s. Each frame contained 150 dots, with a size of 0.1° and separated by 0.18°. The code for generating Glass patterns was adapted from a code generously provided by Dr. J. Anthony Movshon. We used a Macintosh Pro laptop running Psychtoolbox-3 for Apple OS X under MATLAB (64-bit, version 8.4.0) to create and display visual stimuli with an Intel Iris Pro 1024 MB video card on a retina display. The mean luminance was 0.59 cd/m2 for the green pattern, 0.54 cd/m2 for the red pattern, and 0.60 cd/m2 for the white pattern. The luminance of the fixation point was 0.28 cd/m2. The background luminance was 0.19 cd/m2.

Fig. 1.

Perceptual decision-making task. A: example images of Glass patterns. The strength of the sensory information contained in the Glass pattern varies with the number of correlated dots (coherence). Examples shown are 0% (no information about orientation), 13%, 35%, and 100% (all pairs sharing same orientation). B: example red and green rightward Glass patterns are shown, each with 100% coherence. This illustrates one example session in which the red Glass pattern is associated with equal orientation priors (50:50) and the green Glass pattern is associated with unequal orientation priors (75:25). In this example, the rightward orientation occurred more often. The direction of the orientation priors and the color with which they were associated were counterbalanced across participants. C: spatial and temporal arrangement of the task. The boxes indicate the visual display. The black spots show the fixation spot at the center, and the 2 choice targets appear peripherally, indicating the 2 possible orientations. The Glass pattern appears at the central location. Participants indicated what direction they perceived by pressing the “O” (leftward) or the “P” (rightward) key on a computer keyboard using one hand, illustrated by the finger. Participants heard a low pitch tone (a beep) for every correct trial and received no feedback for incorrect trials, illustrated by the audio symbol. No explicit reward was provided. D: proportion of positive (leftward) choices is plotted against orientation strength for 12 healthy people (HC; 5 men, 7 women, mean age 63 yr). These data are fitted with a logistic function and provide a measure of the response bias (α) and the slope or sensitivity of the psychometric function (β). The parameters of the fits were used to compare performance between the equal and unequal prior conditions within groups. The gray diamond and line show the data and the logistic fit in the equal prior trials (50:50). Age- and sex- matched HC make accurate decisions in conditions of sensory certainty (100%). Their performance decreases as sensory information becomes less clear (35% and 13%) and reaches chance level when sensory information is ambiguous (0%) and participants guess. E: comparisons between the equal and unequal prior conditions in participants presented with more frequent positive orientation during the unequal prior trials. The gray lines and upward triangles show the data in the equal prior trials (50:50), whereas the black lines and upward triangles show the data for unequal positive prior trials (25:75). F: same as in E in participants presented with more frequent negative orientation during the unequal prior trials. The gray lines and downward triangles show the data in the equal prior trials (50:50), whereas the black lines and downward triangles show the data for unequal negative prior trials (75:25). G: logistic fits, α and β parameters, for the fits in the negative, equal (for negative), equal (for positive), and positive prior trials (*P = 0.04, paired t-test). Error bars are SE. Data in this group are from Perugini et al. (2016).

Task design.

We used an orientation discrimination task that we recently developed (Perugini et al. 2016). Participants must determine the orientation of Glass pattern stimuli with strong or weak sensory information. On each trial, either a red or a green Glass pattern appeared on the screen. After the initial block of practice trials with 100% coherence stimuli, we presented 320 green Glass patterns and 320 red Glass patterns with the four levels of coherence (100%, 35%, 13%, and 0%), for a total of 640 trials. We manipulated prior information by randomly assigning one color to the equal prior condition and the other color to the unequal prior condition (Fig. 1B). In this way, the two directions, leftward or rightward, occurred randomly for only one colored stimulus (equal prior, 50:50) and occurred 75:25 for the other colored stimulus (unequal prior) (Fig. 1B). We counterbalanced the direction and the color of the stimulus associated with the unequal priors across participants. In this task, the implicit statistics that participants learned are subtle, because among all the stimuli that appeared during one session (320 green and 320 red), only 62.5% were oriented in the same direction. With this design we were able to collect equal (one color) and unequal prior (other color) trials at essentially the same time point because the red or green Glass pattern occurrences were randomly interleaved, excluding the risk of fatigue or practice confounds. At the beginning of each trial, participants maintained their gaze on a centrally located fixation point (1,000 ± 200 ms, determined from an exponential distribution to avoid timing prediction). Two choice targets then appeared, indicating the two possible orientations, followed by the onset of the Glass pattern stimulus (Fig. 1C). Participants were informed that they could report their choice as soon as they decided [reaction time (RT) task], but the centrally located spot remained illuminated to encourage continued fixation. We excluded trials with RTs <200 ms, thereby eliminating trials with non-sensory-based choices. For every trial there was a randomized minimum trial duration between 1,800 and 2,200 ms. If no decision was made in at least this time, the trial was aborted automatically and for all participants. Participants reported their decisions by pressing a button on a keyboard (O = left choice; P = right choice) with their dominant hand. Auditory feedback occurred immediately (~50 ms) after every correct response, and no feedback occurred for error trials. Participants became familiar with the feedback during the practice trials. Because it takes time to accumulate the priors in this task (Perugini et al. 2016), we show only the data from the second half of the experimental block.

Data analysis.

The data from HC participants appear elsewhere (Perugini et al. 2016). We used MATLAB R2014b to analyze the data and make the plots. We fitted the psychometric data with a logistic function of the form, p(P) = λ + (1 − 2λ)/{1 + exp[−β(C − α)]}, where p(P) is the proportion of positive choices and C is dot pair coherence. α and β are free parameters determined using maximum likelihood methods and provide a measure of the slope or sensitivity of the psychometric function (β) and the response bias (α). The lapse rate λ is the difference between the asymptote of the function and perfect performance, and it is associated with transient lapses in attention during task performance (Wichmann and Hill 2001). We assessed normality of the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test corrected with Lilliefors significance. We assessed the use of priors by comparing the α values between the equal and the unequal prior condition within groups (paired t-test), and we assessed changes in the sensitivity by comparing the β values between equal and unequal prior conditions within groups (paired t-test). To compare the use of the priors across groups of participants, we measured the proportion of more frequent choices for the most difficult stimulus conditions, when prior information is most informative (0% and 13% coherence), and separately for the equal and unequal prior conditions. For example, for leftward prior sessions, we calculated the proportion of trials in which participants chose “left” for both the equal and unequal prior trials, and then we calculated the same quantity for the rightward prior sessions for both the equal and unequal prior trials. We then reflected the rightward trials and averaged these with the leftward trials to generate an overall proportion of more frequent choice quantity. To assess whether the BDI, BAI, UPDRS, or Fahn-Marsden scale scores predicted the use of prior in all groups, we performed a linear regression analysis between the use of the prior (calculated by the proportion of more frequent choices in the unequal prior trials minus the proportion of more frequent choices in the equal prior, for the most difficult stimuli) and the BDI in all participant groups, the BAI and UPDRS scores in people with PD, and the Fahn-Marsden scale scores in people with dystonia (Table 1; Fig. 3A and Fig. 4E). Because half of the people with dystonia were taking benzodiazepine (Table 2), we assessed the influence on benzodiazepine on task performance by using a Pearson correlation between the use of the prior and the presence/absence of benzodiazepine.

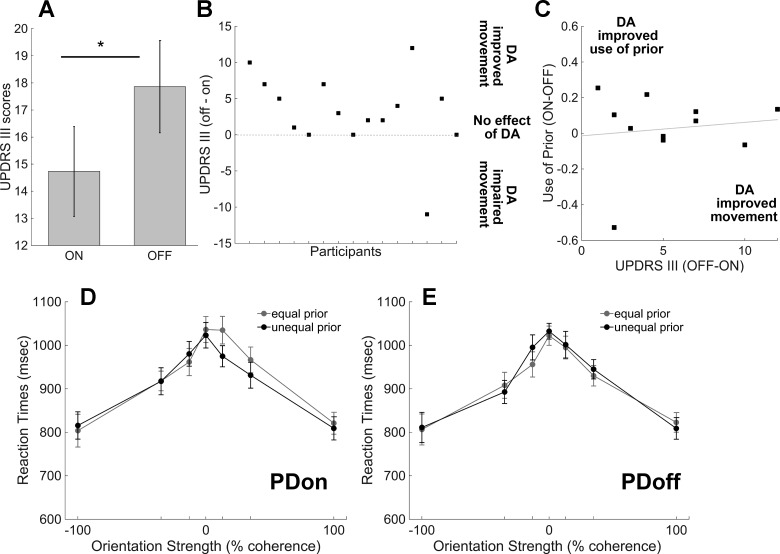

Fig. 3.

Dopamine (DA) medications improve motor symptoms. A: plot shows the UPDRS III scores for PDon (15 ± 1.66) and PDoff (18 ± 1.7). Significantly higher scores during the off session indicate that abstinence from DA medications impaired movement in people with PD [UPDRS III on vs. off, t(14) = 2.27, P = 0.039, paired t-test]. B: plot shows the “difference” UPDRS III scores between off and on session for each patient. Each square represents a value obtained by subtracting the UPDRS score when patients were on medications from the UPDRS score when patients were off medications. A positive value means that medications improve patients’ motor symptoms (UPDRS scores off > on, n = 11). A negative value means that medications worsen patients’ motor symptoms (UPDRS OFF < on, n = 1). A value equal to 0 means that medications did not affect patients’ motor symptoms during assessment (UPDRS off = on, n = 3). C: “difference” use of prior (proportion of more frequent choices for PDon minus proportion of more frequent choices for PDoff) against UPDRS III scores for PDoff minus UPDRS III scores for PDon. We plotted data only from people with PD who had improved motor behavior with DA (n = 11). Positive values on the x-axis mean that DA improved motor behavior, and positive values on the y-axis mean that DA improved use of the prior at the decision-making task. There is no correlation between the effects of DA on the use of prior and on motor behavior (r = 0.12, P = 0.7). D: plot shows the distribution of the reaction times (RT) in milliseconds (msec) across orientation strength for correct trials in PDon. Black circles show the unequal prior trials (75:25/25:75), and gray circles show the equal prior trials (50:50). It is important to note that the RT shown include sensory, motor, and decision times. E: same as in D for PDoff. Error bars are SE.

We computed the proportion of win-stay and lose-shift by using a model that takes into account coherence levels, correct or incorrect choice (feedback or no feedback), and equal and unequal prior trials. For the win-stay strategy, we counted the total number of times that participants repeated the same response after a correct trial. We then divided the number of response repeats by the total number of correct trials to obtain the proportion of win-stay. For the lose-shift, we counted the total number of times that participants changed their response after an error trial. We then divided the number of response changes by the total number of incorrect trials to obtain the proportion of lose-shift. We present results for the 0% coherence trials only (Fig. 5), because these trials are driven exclusively by prior information since they contain no orientation information.

Fig. 5.

People with PD and dystonia are not impaired at learning from positive or negative feedback. Graphs show the mean proportion of win-stay (A) and lose-shift (B) in each group, separated in trials with the equal prior stimuli and trials with the unequal prior stimuli with 0% coherence stimuli. Win-stay refers to the proportion of repeating the same response (leftward or rightward) after a correct trial (feedback). Lose-shift refers to the proportion of changing response after an error trial (no feedback). The win-stay and loose-shift trials only represent half of the total trials present in the experiment, for each stimulus color (equal and unequal). Indeed, the total number of trials for each stimulus color is given by summing the win-stay trials, lose-shift trials, win-shift trials (where participants changed response after correct trials), and lose-stay trials (where participants repeated the same response after an incorrect trial). We found a significant difference in the proportions of win-stay between equal and unequal prior trials in all groups, using a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA [F(1,54) = 126, ***P < 0.0001), no difference between groups [F(3,54) = 1.46, P = 0.24], and no significant interaction between groups and prior condition [F(3,54) = 1.76, P = 0.166]. Similarly, we found a significant difference in the proportions of lose-shift between equal and unequal prior trials in all groups [F(1,54) = 43.2, ***P < 0.0001], no difference between groups [F(3,54) = 1.45, P = 0.24], and no significant interaction between groups and prior condition [F(3,54) = 1.88, P = 0.144]. The data show that participants repeated responses that led to a positive outcome more often for the unequal prior stimuli compared with the equal prior stimuli. Conversely, they adopted a lose-shift strategy more for the equal prior trials compared with the unequal prior trials. Error bars are SE.

We performed a 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA to test for significant differences in choice performance between PD on medications (PDon) vs. PD off medications (PDoff) and prior condition, equal vs. unequal. For all remaining comparisons, we performed a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA. The between-group factors were PDon vs. HC, PDoff vs. HC, PDon vs. dystonia, PDoff vs. dystonia, and HC vs. dystonia. The within-group variable was prior condition with two levels, equal and unequal. When appropriate, we performed further post hoc comparisons and simple effects statistics. When appropriate, we also reported the effect size measured by the partial eta squared (η2), which is the variance attributable to an effect divided by the variance that could have been attributable to this effect. It is calculated as η2 = SSeffect/(SSeffect + SSerror), where SS represents the sum of squares. Statistical analyses were run using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh (version 24) and/or Matlab R2014b.

RESULTS

Participants performed a discrimination task in which they observed red and green Glass patterns oriented either leftward or rightward, and reported their orientation decision with a button press. We manipulated the certainty of the sensory information contained in the Glass pattern (orientation strength) by varying the number of correlated dot pairs, ranging from 0% (no information about orientation) to 100% coherence (maximal orientation information; Fig. 1A). Participants performed a total of 640 trials in a session formed by an equal number of red and green Glass patterns (320 each), at 4 levels of coherence (0, 13, 35, 100%), randomly presented across the entire session. We manipulated priors that could be used by participants to bias their choices when uncertain about the sensory information by varying the frequency of occurrence of either the leftward or rightward orientation. The manipulation occurred for only one of the colored Glass patterns so that one orientation for one colored stimulus occurred more often (75%, unequal prior). Within the same session, the probability of the leftward or rightward orientation for the other colored stimulus remained equal (50%, equal prior; Fig. 1B). This manipulation allowed participants to develop an orientation prior in a stimulus-specific manner implicitly but did not rely on presentation of equal and unequal prior conditions in separate blocks, thus eliminating the possibility of fatigue effects. Figure 1C shows the full sequence of the task. We previously showed that trial-by-trial feedback (a beep) is required to learn the stimulus-specific orientation prior and that the use of the prior is maximal after ~300 trials (Perugini et al. 2016). Thus we report performance of participants during the last 320 trials of the entire session when the use of the prior is greatest.

As we reported previously, healthy age- and sex-matched control participants (HC) perform the perceptual decision task well: they perceive orientation in Glass patterns when the sensory signals are strong, they are able to report those decisions with the button press, and they use the previously learned information to guide their decisions when sensory information is weak (Fig. 1, D–F, and see Perugini et al. 2016). When the sensory signal is weak, HC distribute their choices equally between left and right, for the equal prior trials, indicating they are guessing (0% orientation strength in Fig. 1D and Fig. 1, E and F, gray triangles and lines). For the unequal prior trials, decisions are biased toward the orientation that occurred more frequently, indicating that HC learn and use the task statistics when the sensory information is weak (Fig. 1, E and F, black triangles and lines). For leftward prior sessions, we calculated the proportion of trials in which participants chose left for both the equal and unequal prior trials (Fig. 1E), and we calculated the same quantity for the rightward prior sessions for both the equal and unequal prior trials (Fig. 1F). We then reflected the rightward trials and averaged these with the leftward to generate an overall proportion of more frequent choice quantity. Consistent with a guessing strategy for the weak sensory stimulus conditions (0 and 13%) in the equal prior trials, the overall proportion of more frequent choices was 0.53 ± 0.03, and for the unequal prior trials, the proportion of more frequent choices was significantly different, 0.62 ± 0.03 [t(35) = −4.061, P < 0.001, paired t-test]. We fitted the performance data with logistic functions and compared the bias (α) and sensitivity (β) parameters between the equal and unequal prior conditions. To increase statistical power, we collapsed over positive and negative prior conditions and found a change in the bias between prior conditions [Fig. 1G, top; t(11) = −1.80, P = 0.04, paired t-test] and no change in the sensitivity [Fig. 1G, bottom; t(11) = −0.10, P = 0.92, paired t-test].

We also reported previously that people with PD show impairments in using previously learned information for making decisions compared with HC, and we replicated that finding in the current study in a new group of 15 participants. People with PD were able to discriminate orientation in the Glass pattern stimulus and report their choices with a button press, and like HC, they guessed for the weak sensory stimuli (0% and 13% coherence). These results show that people with PD have intact perceptual and motor processes required to perform this task (Fig. 2A). However, in contrast to HC, people with PD failed to show biases in choice performance in the unequal prior trials when the discrimination was difficult (0 and 13% coherence). The overall proportion of more frequent choices for the equal and unequal prior trials were the same and statistically indistinguishable [cf. Fig. 2B for positive prior and Fig. 2C for negative prior; 0.53 ± 0.03 and 0.53 ± 0.03; t(44) = −0.026, P = 0.98, paired t-test]. We also found no differences in the α and β parameters of the logistic functions fitted to the performance data for the different prior conditions in people with PD [cf. Fig. 2D; α: t(14) = 0.43, P = 0.66; β: t(14) = 0.83, P = 0.42, paired t-test]. Finally, a comparison of the proportion of more frequent choices in the unequal prior trials for HC (0.62 ± 0.03) and people with PD (0.53 ± 0.03) showed statistically significant differences. Using a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA, we found a main effect of prior condition [F(1,79) = 5.445, P = 0.022, η2 = 0.06] and a significant interaction between prior and groups [F(1,79) = 5.260, P = 0.024, η2 = 0.06]. Simple main effects analysis showed that PD and HC chose the more frequent orientation similarly in the equal prior trials [F(1,79) = 0.002, P = 0.962], but their choices differed in the unequal prior trials [F(1,79) = 5.132, P = 0.026]. This represents an unequivocal replication of our previous findings showing impaired performance on a decision-making task when there is a reliance on previously learned information in people with PD.

Fig. 2.

Dopamine medications do not affect the ability to use priors in perceptual decision-making performance in PD. A: proportion of positive choices is plotted as a function of orientation strength for a group of 15 people with PD (6 men, 9 women, mean age 64 yr) after taking dopaminergic medications. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1D. PDon are able to perform the task well based on the amount of sensory information provided, and they guess when sensory information is ambiguous. This rules out interpretations based on motor or perceptual impairments. B: comparisons between the equal and unequal prior conditions for participants presented with more frequent positive orientation during the unequal prior trials. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1E. PDon are not able to bias their choices based on prior information. C: same as in B for participants presented with more frequent negative orientation during the unequal prior trials. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1F. D: logistic fits, α and β parameters, for PDon. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1G. E: same as in A for the same 15 people with PD, but after at least 16 h of withdrawal and abstinence from dopaminergic medications. F: same as in B for PDoff. G: same as in C for PDoff. H: same as in D for PDoff. Error bars are SE.

Impaired use of priors for decision-making in PD is independent of dopaminergic tone.

Because our previous work as well as the replication of the finding described above occurred in people with PD while on their DA medication, we next asked whether the impairment we found is influenced by dopaminergic tone. One possibility is that the DA medication itself causes the impairment in the ability to express a bias in decision-making. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the performance of HC to that of people with PD on and off dopaminergic medication. The same 15 people with PD reported above and whose data are shown in Fig. 2, A–D (PDon), participated in a second session off medication. The order of the sessions PDon or PDoff was counterbalanced across participants so that some people were tested on their medications first, whereas some people were tested off their medications first.

We found that abstinence from dopaminergic medication for at least 16 h for fast acting, and for at least 24 h for slow-release dopaminergic medications, a typical time for studies assessing the influence of dopaminergic tone in PD (Foerde et al. 2013a; Frank et al. 2007; Shiner et al. 2012), did not affect the ability of people with PD to make decisions with strong sensory information (Fig. 2E), indicating that PDoff can discriminate the orientation signal in the Glass pattern and correctly press the keys to indicate their choices. However, PDoff chose the more frequent orientation at the same rate in the equal and unequal prior trials for weak sensory stimuli (0 and 13%) indicating they were guessing for both conditions (Fig. 2, F and G) and, therefore, not expressing a bias based on the previously learned information. The proportion of more frequent choices for the equal prior trials was 0.52 ± 0.03, and that for the unequal prior trials was 0.52 ± 0.02 [t(44) = −0.229, P = 0.820, paired t-test]. Fitting logistic functions to the data and comparing the parameter fits also confirmed this finding (Fig. 2H). Figure 2, F and G, shows the psychometric functions for PDoff for the equal (gray triangles and lines) and for the unequal positive (Fig. 2F) and the unequal negative (Fig. 2G) prior conditions, respectively. Figure 2H shows the parameter fits. Neither the α nor the β parameters of the fits differed between the prior conditions [α: t(14) = −1.92, P = 0.96; β: t(14) = −1.38, P = 0.188, paired t-test]. We compared the performance of PDoff with that of HC and confirmed that PDoff performed differently compared with HC only in the unequal prior condition (0.52 ± 0.02 vs. 0.62 ± 0.03) but not in the equal prior condition (0.52 ± 0.03 vs. 0.53 ± 0.03). These differences were confirmed statistically using a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA comparing choice performance between PDoff and HC in the equal and unequal prior conditions. As found for PDon, we found a main effect of prior condition in PDoff [F(1,79) = 9.499, P = 0.003, η2 = 0.11] and a significant interaction between prior and group [F(1,79) = 7.670, P = 0.007, η2 = 0.09]. Simple main effects analysis showed that PDoff and HC chose the more frequent orientation similarly in the equal prior conditions [F(1,79) = 0.085, P = 0.77], but they differed in the unequal prior condition [F(1,79) = 7.645, P = 0.007]. Finally, comparing the performance of PDoff and PDon, we found that regardless of medication status, people chose the more frequent orientation at the same rate for the equal prior trials (0.52 ± 0.03 vs. 0.53 ± 0.03) and for the unequal prior trials (0.52 ± 0.02 vs. 0.53 ± 0.03). The similar performance between PDoff and PDon was confirmed statistically using a 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA: there was no significant main effect of medication on proportion of choices [F(1,89) = 0.026, P = 0.87, η2 = 0.001]. On the basis of these results, we conclude that the inability to use priors to bias perceptual decisions occurs in PD regardless of dopaminergic medication status and is thus independent of dopaminergic tone.

Given that the levels of DA failed to influence performance on the decision task, we next asked whether DA affected motor behavior in our sample of people with PD. We tested motor behavior in PDon and PDoff during the same visits they made to perform the decision-making task. In contrast to decision-making performance, PD off DA medication showed higher UPDRS part III scores compared with PD on DA medication, indicating that DA improved motor symptoms. The mean motor score in PDon was 15 ± 1.6, and the mean score for PDoff was 18 ± 1.7 [t(14) = 2.27, P = 0.039, paired t-test; Fig. 3A]. A closer analysis showed that 11/15 patients showed improved motor behavior when on medications; 3/15 patients showed no improvements when on medications; and 1/15 patient showed a deterioration of motor behavior when on medications (Fig. 3B).

We also compared performance in the decision task after removing the four participants for whom DA medication did not improve motor behavior. Exclusion of these participants did not change the behavioral findings; for PDon the proportion of more frequent choices in the equal prior trials was 0.49 ± 0.03, and for the unequal prior trials was 0.50 ± 0.03 [t(32) = −0.44, P = 0.966, paired t-test]. For PDoff, the proportion of more frequent choices in the equal prior trials was 0.52 ± 0.02, and for the unequal prior trials was 0.50 ± 0.02 [t(32) = 0.97, P = 0.339, paired t-test]. Finally, we compared the influence of DA on motor performance directly to the influence of DA on decision-making performance by plotting the proportion of more frequent choices on medication minus the proportion of more frequent choices off medication against the UPDRS III score off minus the UPDRS score on medication. These calculations normalize the data for direct comparison so that positive values indicate improvement with DA. Figure 3C shows that there was no relationship in the improvement in motor scores in PD and their ability to use prior information to bias perceptual decisions (r = 0.12, P = 0.7). We also compared RTs for people with PDon and PDoff and HC, although it is important to note that RT in this task includes visual processing time, decision time, and movement time, so it is not a pure movement measure. RT increased as orientation strength decreased, and RT was longest when there was no orientation information for HC, PDon, and PDoff, consistent with an integration process for perceptual decision-making. Furthermore, we found that people with PD are slower than HC in both equal (HC: 779 ± 33; PDon: 935 ± 35; PDoff: 920 ± 31) and unequal prior conditions (HC: 796 ± 42; PDon: 922 ± 31; PDoff: 927 ± 35), confirming previous work showing that PD is associated with cognitive and motor slowness (Bloxham et al. 1987; Vlagsma et al. 2016). This difference between groups was supported statistically [main effect of group: F(2,291) = 30.14, P < 0.0001, η2 = 1.72]. However, although the influence of DA appears to decrease RT for PDon compared with PDoff, particularly for one side, this difference did not reach statistical significance [PDon: 934 ± 46 ms; PDoff: 947 ± 49 ms; t(44) = −0.9, P = 0.37, paired t-test]. The lack of an influence of DA on RT in decision tasks is consistent with previous work (Huang et al. 2015). In fact, that DAergic medications do not affect RT in this task is further support that DA is not involved in this type of decision-making. On the basis of these combined results, we conclude that in PD, the impairment in the ability to use priors for perceptual decisions is independent of dopaminergic tone and is dissociable from motor impairment.

A critical concern in all studies using people with PD on or off medication is that there is an ongoing and long-term degenerative process that is being treated by dopaminergic medication. Therefore, even though tonal levels of dopamine are different in people on and off medications, it is still possible that the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in PD and/or the long-term treatment with dopamine medication alters dopaminergic function. This could explain the impaired use of priors. A way to assess this possible explanation is to test people who have another disorder that involves the basal ganglia, like PD, but that is not degenerative and has not required treatment with dopaminergic medication. An ideal patient population is those with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia. This disease involves the basal ganglia but does not involve DA neuronal cell loss, is not treated by DA medications, and is not thought to involve the frontal cortex (Cloud and Jinnah 2010; Jinnah et al. 2013). If we find that people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia show impairments in the use of priors as do people with PD, this would support the hypothesis that the impairment in the use of priors is unlikely to be due to DA neuronal degeneration, long-term treatment with dopaminergic drugs, or impaired frontal cortex.

Figure 4 shows the psychometric functions fitted to the choice performance data from 16 people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia. People with dystonia were capable of discriminating orientation in the Glass patterns and reporting their choices with button presses (Fig. 4A), indicating intact perceptual and motor processing in this task. However, they failed to incorporate prior information to bias their choices for the weak sensory stimulus conditions (Fig. 4B for positive unequal prior and Fig. 4C for negative unequal prior, black triangles and lines). Figure 4D shows the α and β parameters from the logistic functions for the equal and unequal prior conditions, and the results of statistical analysis show no differences for either prior condition [α: t(15) = −1.40, P = 0.09; β: t(15) = 1.45, P = 0.17, paired t-test]. People with focal dystonia showed no differences in the proportion of more frequent choices in the equal (0.55 ± 0.02) and unequal (0.55 ± 0.03) prior trials [t(47) = −0.271, P = 0.787, paired t-test]. We compared the performance of HC and people with dystonia using a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA and found a significant main effect of prior [F(1,82) = 6.19, P = 0.01, η2 = 0.07] and a significant interaction between prior and group [F(1,82) = 4.32, P = 0.04, η2 = 0.05]. The effect of prior indicated a difference between the equal and unequal prior conditions in HC [F(1,82) = 9.13, P = 0.003] but not in people with dystonia [F(1,82) = 0.09, P = 0.755], as well as a difference in performance between HC and people with dystonia only in the unequal prior condition [F(1,82) = 3.94, P = 0.049] but not in the equal prior condition [F(1,82) = 0.001, P = 0.98]. As we saw in PD, motor behavior showed impairments as measured by the Fahn-Marsden dystonia scale, but this too did not correlate with the ability to use the priors to guide decisions (r = 0.03, P = 0.9; Fig. 4E). Note also that 8/16 of people with dystonia were taking benzodiazepines during the task performance, but we found no correlation between the ability to use the priors and the use of this medication, indicating this did not contribute to the impairment (Pearson’s r = −0.2, df = 16, P = 0.45). Consistent with previous work showing that people with dystonia are generally slower than HC (Buccolieri et al. 2004; Filip et al. 2013), we found that people with dystonia showed slower RT compared with HC for both equal (HC: 779 ± 33; dystonia: 899 ± 36) and unequal (HC: 796 ± 42; dystonia = 890 ± 36) prior conditions, but their RT were similar to those for people with PDon and PDoff. This was confirmed statistically [main effect of groups: F(3,402) = 19.49, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.13; Bonferroni multiple comparisons: dystonia vs. HC, P = 0.000001; dystonia vs. PDon, P = 0.49; dystonia vs. PDoff, P = 0.82].

The data show that people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia and PDon performed similarly, as indicated by the similar proportion of more frequent choices for equal prior trials (0.55 ± 0.02 vs. 0.53 ± 0.03) and for unequal prior trials (0.55 ± 0.03 vs. 0.53 ± 0.03). The similarity was confirmed statistically with a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA showing a main effect of prior [F(1,91) = 0.04, P = 0.83, η2 = 0.001], a prior × group interaction [F(1,91) = 0.03, P = 0.86, η2 = 0.001], and a main effect of group [F(1,91) = 0.008, P = 0.93, η2 = 0.001]. People with dystonia were also similar qualitatively or quantitatively to PDoff in their proportions of choosing the more frequent orientation in the equal prior trials (0.55 ± 0.02 vs. 0.52 ± 0.03) or the unequal prior trials (0.55 ± 0.03 vs. 0.52 ± 0.02). This similarity was also confirmed statistically with a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA showing a main effect of prior [F(1,91) = 0.12, P = 0.73, η2 = 0.001], a prior × group interaction [F(1,91) = 0.008, P = 0.93, η2 = 0.001], and a main effect of group [F(1,91) = 0.17, P = 0.68, η2 = 0.002]. These results show that people with focal dystonia are impaired neither at perceptual processing nor in making motor responses required in this task. Rather, they are impaired at incorporating priors to bias perceptual decisions in a manner similar to that seen in people with PD whether on or off DA medications. Taking these findings together, we conclude that it is unlikely that dopamine plays a role in the ability to incorporate memories for perceptual decisions, and it is also unlikely that frontal cortex plays a role in this aspect of decision-making.

Impaired use of priors in basal ganglia disease is independent of learning strategy.

Given that PD is associated with reinforcement learning impairments (Frank et al. 2004; Knowlton et al. 1996; Shohamy et al. 2004), it is possible that this deficit extends also to the ability to learn priors. Similarly, given that people with DYT1 dystonia, a rare and inherited form of dystonia, are impaired at reinforcement learning (Arkadir et al. 2016), it is possible that a similar deficit is present also in people with focal dystonia, explaining their inability to show a bias based on previously learned information. Our previous work suggests that a lack of learning the prior cannot explain the results in PD, because people with PD on DA medication show adjustments of the rate of sensory evidence accumulation specifically for the color associated with the unequal prior, as assessed by modeling with the drift diffusion model. Also, we performed an experiment in which we told participants what the prior was explicitly, so the task did not require learning, and people with PD still showed impairment (Perugini et al. 2016). In this study, rather than relying on model parameter fits, we assessed directly the ability to learn the prior by determining whether people with PD and dystonia showed similar learning strategies to those seen in healthy participants. We measured the likelihood of repeating the same choice after a correct trial (win-stay) and the likelihood of switching to the other choice after an incorrect trial (lose-shift) for each participant group for the 0% coherence condition, and separately for the equal and unequal prior trials. Note that the 0% coherence condition was associated with feedback on half of the trial randomly, on a trial-by-trial basis, so an optimal strategy would be to use equal numbers of win-stay, win-shift, lose-stay, and lose-shift for the equal prior condition. For the unequal prior condition, an optimal strategy would be to repeat the same response after a correct trial or to switch response after an incorrect trial. Note also that the ability to use a win-stay or lose-shift strategy is not informative about performance or the overall number of correct and incorrect trials. As such, we could assess the use of priors in perceptual decision-making as shown in Fig. 1, D–F, and Figs. 2 and 4 separately from strategy, to ensure that participants had the opportunity to express the bias but, for some other reason, failed to do so. Figure 5 shows the results comparing the win-stay and lose-shift strategies in all participants. We found that HC, PDon, PDoff, and people with dystonia all used the same win-stay strategy more for the unequal prior trials compared with the equal prior trials (Fig. 5A, HC, white bars: 0.34 ± 0.01 for the equal and 0.59 ± 0.02 for the unequal; PDon, dark gray bars: 0.36 ± 0.018 for the equal and 0.53 ± 0.02 for the unequal; PDoff, light gray bars: 0.40 ± 0.01 for the equal and 0.55 ± 0.017 for the unequal; dystonia, black bars: 0.36 ± 0.02 for the equal and 0.52 ± 0.03 for the unequal), a finding confirmed by a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA showing a significant effect of prior condition [F(1,54) = 126, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.7], no main effect of group [F(3,54) = 1.46, P = 0.24, η2 = 0.07], and no significant interaction between group and prior conditions [F(3,54) = 1.76, P = 0.166, η2 = 0.09].

In contrast to the win-stay strategy, the lose-shift strategy was observed more often for the equal prior trials than for the unequal prior trials and all participant groups showed this strategy (Fig. 5B, HC, white bars: 0.64 ± 0.02 for the equal and 0.55 ± 0.02 for the unequal; PDon, gray bars: 0.60 ± 0.02 for the equal and 0.50 ± 0.02 for the unequal; PDoff, light gray bars: 0.65 ± 0.02 for the equal and 0.47 ± 0.02 for the unequal; dystonia, black bars: 0.60 ± 0.02 for the equal and 0.52 ± 0.03 for the unequal), a finding confirmed by a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA showing a significant effect of prior condition [F(1,54) = 43.2, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.44], no main effect of group [F(3,54) = 1.45, P = 0.24, η2 = 0.07], and no significant interaction between group and prior conditions [F(3,54) = 1.88, P = 0.144, η2 = 0.09]. These results show that all participant groups use similar learning strategies: a win-stay strategy is used predominantly for the unequal prior trials, whereas a lose-switch strategy dominates for the equal prior trials. Despite significant differences in choice performance between people with PD and focal dystonia compared with HC, there is no difference in the win-stay/lose-shift strategy employed by these participant groups. Taken together, our previous and new results suggest that the impairment in using priors for decision-making is unlikely to result from impairments in learning. Moreover, because a correct choice always corresponded to positive feedback and an incorrect choice always corresponded to no feedback, these results also show that people with PD, whether on or off their dopaminergic medication, are able to learn from both positive and negative feedback, a finding that is consistent with recent results showing a dissociation between learning and performance in people with PD (Grogan et al. 2017). Altogether, our data show that, in addition to the well-known DA-dependent reinforcement-learning deficit in PD (Frank et al. 2004), there is a novel impairment in the ability to use priors for perceptual decision-making in PD that is independent of dopaminergic tone and is dissociable from motor symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The results reported in this article show that the ability to use previously learned information to bias perceptual decisions is impaired in people with PD whether on or off DA medications. Importantly, people with PD were able to make decisions about Glass pattern orientation and were able to report choices with strong sensory information, indicating intact perceptual and motor processes. Furthermore, they also showed a win-stay, lose-shift strategy of learning that was statistically indistinguishable from that seen in healthy participants, ruling out an impairment based on learning the priors. Finally, people with PD showed improved motor performance with DA that was independent of the use of priors in the perceptual decision task, revealing a cognitive symptom that is dissociable from the motor symptoms in PD. People with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia showed impaired use of memory information to bias perceptual decisions similar to that seen in people with PD. Also like PD, the impairment in cognition in dystonia did not correlate with the motor impairment and cannot be explained by an impairment in learning. Together, the data reveal a novel cognitive impairment in focal dystonia and show that memory-based decision-making is independent of dopaminergic tone and also likely to be independent of frontal cortex involvement, because people with focal dystonia are not generally considered to have frontal cortical impairment (Neychev et al. 2011).

Relationship to previous findings.

A number of studies have shown that dopaminergic treatment improves some cognitive deficits in people with PD but impairs, and even produces, others (Foerde and Shohamy 2011b; Foerde et al. 2013a; Kehagia et al. 2013; MacDonald et al. 2011; Shohamy et al. 2004, 2006; Vo et al. 2014; Wolpe et al. 2015). An explanation for these mixed effects of dopamine treatment is offered by the “dopamine overdose hypothesis,” which involves different effects of dopamine on the nigrostriatal-dorsolateral frontal cortical circuits and the ventrostriatal-orbitofrontal circuits, the latter being less impaired in PD than the former (Cools et al. 2001; Gotham et al. 1988; Rowe et al. 2008; Swainson et al. 2000; Vaillancourt et al. 2013). Tasks that show impairments with dopamine treatment compared with off dopamine treatment include those requiring probabilistic reversal learning (Cools et al. 2001), use of learned negative values for decision-making (Frank et al. 2004), and working memory (Frank et al. 2004; Warden et al. 2016). It is possible that the ability to incorporate priors for perceptual decisions might include aspects of some of these cognitive processes, and as such, we would predict that this could explain the impairments we see in PDon. If true, then removing people from their dopaminergic medications should improve decision-making performance, but that is not what we found. People with PD were equally impaired whether on or off their medications, ruling out the overdose hypothesis as an explanation for this particular decision-making impairment. Many of these same studies find that dopaminergic medications improve performance during task switching (Cools et al. 2001) and in tasks that require use of learned positive values for decision-making (Frank et al. 2004, but see Grogan et al. 2017). It is also possible that the ability to link the prior in a stimulus-specific manner as required in our task might include some kind of task switching. In this case, we would expect that PDoff would be impaired and PDon would show improvement. Again, that is not what we find. Both PDon and PDoff show impairment in the ability to use prior information to guide perceptual decision-making.

Other work suggests that the timing of feedback in learning tasks is critical to reveal impairments in PD (Foerde and Shohamy 2011a; Foerde et al. 2013a, 2013b). People with PD on dopaminergic medication can learn from feedback if it occurs with a delay of a few seconds (7,000 ms), but are impaired if feedback occurs sooner after the choice (1,000 ms; Foerde and Shohamy 2011a). Thus a possible explanation of why people with PD are impaired in our task is because they are impaired at learning the priors, since we provided the feedback within 50 ms, even shorter than the shortest time used previously. There are four reasons we believe this is an unlikely explanation. First, people with PD implement win-stay and lose-shift learning strategies just as healthy participants do, indicating some understanding of the prior. Second, our previous work found that the ability of people with PD to use prior information is improved if the prior is linked to only a single stimulus feature even if the feedback occurs within ~50 ms (Perugini et al. 2016). Third, we previously modeled the performance of people with PD using the drift diffusion model and found that even though people were impaired at expressing the bias, they nonetheless could adjust their rate of sensory evidence accumulation, indicating that they likely learned about the priors and their stimulus specificity (Perugini et al. 2016). Finally, our previous work found that providing explicit instructions to people with PD about the priors, bypassing the learning requirement, failed to improve performance (Perugini et al. 2016), again ruling out an interpretation based exclusively on learning. Whether or not timing plays a role for people with focal dystonia remains an open question.

Implications for perceptual decision-making and basal ganglia disease.

How then might we understand the present findings? Our work is similar to previous work showing that perceptual decisions based on sensory information alone are independent of DA (Costa et al. 2015; Hauser et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2015) (but see Huang et al. 2015; Vilares and Kording 2017; Wei et al. 2015). However, if perceptual decisions are based on associations between stimuli and past rewarding outcomes, DA becomes critical, consistent with its role in value outcome assessment (Lak et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2015; Nagano-Saito et al. 2012; Nomoto et al. 2010). Recent experimental work in humans shows that memory can bias value-based decisions in a way that cannot be explained by a reinforcement learning model (Bornstein et al. 2017; Bornstein and Norman 2017), in line with our finding that reinforcement learning cannot explain the impairment in memory-based perceptual decision-making. A recent idea is that memory for past experience is essential for value-based decisions (Shadlen and Shohamy 2016). The authors advance the hypothesis that the recall of a memory of an outcome leads to the assignment of values to the stimulus associated with that outcome, which then updates a decision variable, suggesting that memory-based decision-making and value-based decision-making interact. This model, consistent with experimental reports in humans (Duncan and Shohamy 2016; Gluth et al. 2015; Kumaran et al. 2009; Murty et al. 2016; Weilbächer and Gluth 2017; Wimmer and Shohamy 2012; Yu and Frank 2015; Zeithamova et al. 2012), proposes an interaction between circuits in the medial temporal lobe encoding memories, striatal and orbitofrontal circuits encoding values, and the decision variable encoded in the lateral intraparietal area of cortex. Because our results show that biases in perceptual decisions based on memories are independent of DA in PD and occur in people with dystonia who do not have DA neuronal cell loss and are unlikely to have frontal cortical involvement, it is possible that medial temporal lobe and its connections with the basal ganglia play a role in biasing perceptual decisions based on the memory of stimulus feature information. Indeed, consistent with this, PD and dystonia are now considered multisystem disorders that likely involve circuits outside of the dopaminergic system (Bohnen and Albin 2011; Buddhala et al. 2015; Müller and Bohnen 2013; Neychev et al. 2011; Perez-Lloret and Barrantes 2016; Tanner et al. 2015; Zeighami et al. 2015). Future studies should be aimed at determining the circuits of perceptual decision-making and how they are impaired in diseases such as PD.

Finally, we report a novel finding that people with focal dystonia are impaired in perceptual decision-making that requires the use of prior information. Although it is now generally accepted that PD is associated with cognitive dysfunction, whether dystonia is associated with cognitive impairment, especially frontal dysfunction, is an active and controversial area of research. Recent evidence suggests that patients with primary dystonia have mild impairments in executive function, including attention, set shifting, and verbal learning (Alemán et al. 2009; Kuyper et al. 2011; Scott et al. 2003; Stamelou et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2017), working memory (Romano et al. 2014), and motor sequence learning. Impairments in decision-making under risk are seen in carriers of the DYT1 mutation (Arkadir et al. 2016; Carbon et al. 2011), a genetic mutation associated with early onset primary dystonia. Several additional lines of evidence also suggest that patients with primary dystonia have deficits in sensorimotor processing that cause alterations in motor control (Abbruzzese and Berardelli 2003; Avanzino et al. 2015; Patel et al. 2014). As far as we are aware, there is little evidence for cognitive impairment implicating the frontal cortex in focal dystonia, but mostly the basal ganglia nuclei (Bollen et al. 1996; Hotson and Boman 1991; Eskow Jaunarajs et al. 2015; Foley et al. 2017; Neychev et al. 2011), and to what extent the impaired circuitry overlaps in these different types of dystonia is unknown. On the basis of our findings that DA does not influence the ability to use priors in perceptual decision-making in people with PD and that people with dopa-unresponsive focal dystonia show a similar impairment, we conclude that frontal cortical DA circuits are unlikely to be involved in the use of prior information in guiding perceptual decisions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Dana Foundation (to M. A. Basso) and National Eye Institute Grant EY013692 (to M. A. Basso).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.P. and M.A.B. conceived and designed research; A.P. performed experiments; A.P. analyzed data; A.P. and M.A.B. interpreted results of experiments; A.P. prepared figures; A.P. drafted manuscript; A.P. and M.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.P. and M.A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. Xueqi Cheng and Mohammed Abdolvahab for programming support, to Adam Myers for administrative support, and to Dr. Joaquin Fuster for continued support. We thank Dr. Irene Litvan for providing infrastructure support for the experiments performed at UCSD. We are especially grateful to all patient participants and to Martha Murphy for helping to recruit people with dystonia. We thank Dr. Barbara Knowlton for critical comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abbruzzese G, Berardelli A. Sensorimotor integration in movement disorders. Mov Disord 18: 231–240, 2003. doi: 10.1002/mds.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemán GG, de Erausquin GA, Micheli F. Cognitive disturbances in primary blepharospasm. Mov Disord 24: 2112–2120, 2009. doi: 10.1002/mds.22736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkadir D, Radulescu A, Raymond D, Lubarr N, Bressman SB, Mazzoni P, Niv Y. DYT1 dystonia increases risk taking in humans. eLife 5: e14155, 2016. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzino L, Tinazzi M, Ionta S, Fiorio M. Sensory-motor integration in focal dystonia. Neuropsychologia 79: 288–300, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Brotchie JM, Gross CE. Pathophysiology of levodopa-induced dyskinesia: potential for new therapies. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 577–588, 2001. doi: 10.1038/35086062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloxham CA, Dick DJ, Moore M. Reaction times and attention in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 50: 1178–1183, 1987. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.9.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen NI, Albin RL. The cholinergic system and Parkinson disease. Behav Brain Res 221: 564–573, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen E, Van Exel E, van der Velde EA, Buytels P, Bastiaanse J, van Dijk JG. Saccadic eye movements in idiopathic blepharospasm. Mov Disord 11: 678–682, 1996. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein AM, Khaw MW, Shohamy D, Daw ND. Reminders of past choices bias decisions for reward in humans. Nat Commun 8: 15958, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein AM, Norman KA. Reinstated episodic context guides sampling-based decisions for reward. Nat Neurosci 20: 997–1003, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nn.4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakefield XO, Blood AJ, Li Y, Hallett M, Hanson PI, Standaert DG. The pathophysiological basis of dystonias. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 222–234, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nrn2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccolieri A, Avanzino L, Marinelli L, Trompetto C, Marchese R, Abbruzzese G. Muscle relaxation is impaired in dystonia: a reaction time study. Mov Disord 19: 681–687, 2004. doi: 10.1002/mds.10711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddhala C, Loftin SK, Kuley BM, Cairns NJ, Campbell MC, Perlmutter JS, Kotzbauer PT. Dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic deficits in Parkinson disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2: 949–959, 2015. doi: 10.1002/acn3.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, Fahn S, Marsden CD, Bressman SB, Moskowitz C, Friedman J. Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias. Neurology 35: 73–77, 1985. doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon M, Argyelan M, Ghilardi MF, Mattis P, Dhawan V, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Impaired sequence learning in dystonia mutation carriers: a genotypic effect. Brain 134: 1416–1427, 2011. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud LJ, Jinnah HA. Treatment strategies for dystonia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 11: 5–15, 2010. doi: 10.1517/14656560903426171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced or impaired cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease as a function of dopaminergic medication and task demands. Cereb Cortex 11: 1136–1143, 2001. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.12.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa VD, Tran VL, Turchi J, Averbeck BB. Reversal learning and dopamine: a Bayesian perspective. J Neurosci 35: 2407–2416, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1989-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Fernández R. Frontostriatal cognitive staging in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2012: 561046, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/561046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KD, Shohamy D. Memory states influence value-based decisions. J Exp Psychol Gen 145: 1420–1426, 2016. doi: 10.1037/xge0000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Bonsi P, Chesselet MF, Standaert DG, Pisani A. Striatal cholinergic dysfunction as a unifying theme in the pathophysiology of dystonia. Prog Neurobiol 127–128: 91–107, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Elton RL; members of the UPDRS Development Committee . Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In: Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease, edited by Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne D, and Goldstein M. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Health Care Information, 1987, p. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Oakes D, Shoulson I, Kieburtz K, Rudolph A, Lang A, Olanow CW, Tanner C, Marek K; Parkinson Study Group . Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 351: 2498–2508, 2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip P, Lungu OV, Shaw DJ, Kasparek T, Bareš M. The mechanisms of movement control and time estimation in cervical dystonia patients. Neural Plast 2013: 908741, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/908741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerde K, Braun EK, Shohamy D. A trade-off between feedback-based learning and episodic memory for feedback events: evidence from Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis 11: 93–101, 2013a. doi: 10.1159/000342000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerde K, Race E, Verfaellie M, Shohamy D. A role for the medial temporal lobe in feedback-driven learning: evidence from amnesia. J Neurosci 33: 5698–5704, 2013b. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5217-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerde K, Shohamy D. Feedback timing modulates brain systems for learning in humans. J Neurosci 31: 13157–13167, 2011a. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2701-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerde K, Shohamy D. The role of the basal ganglia in learning and memory: insight from Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Learn Mem 96: 624–636, 2011b. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JA, Vinke RS, Limousin P, Cipolotti L. Relationship of cognitive function to motor symptoms and mood disorders in patients with isolated dystonia. Cogn Behav Neurol 30: 16–22, 2017. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SH, Henry B, Hill MP, Peggs D, Crossman AR, Brotchie JM. Neural mechanisms underlying peak-dose dyskinesia induced by levodopa and apomorphine are distinct: evidence from the effects of the α2 adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan. Mov Disord 16: 642–650, 2001. doi: 10.1002/mds.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Samanta J, Moustafa AA, Sherman SJ. Hold your horses: impulsivity, deep brain stimulation, and medication in parkinsonism. Science 318: 1309–1312, 2007. doi: 10.1126/science.1146157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O’reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science 306: 1940–1943, 2004. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass L. Moiré effect from random dots. Nature 223: 578–580, 1969. doi: 10.1038/223578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluth S, Sommer T, Rieskamp J, Büchel C. Effective connectivity between hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex controls preferential choices from memory. Neuron 86: 1078–1090, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham AM, Brown RG, Marsden CD. ‘Frontal’ cognitive function in patients with Parkinson’s disease ‘on’ and ‘off’ levodopa. Brain 111: 299–321, 1988. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan JP, Tsivos D, Smith L, Knight BE, Bogacz R, Whone A, Coulthard EJ. Effects of dopamine on reinforcement learning and consolidation in Parkinson’s disease. eLife 6: e26801, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, Leverenz JB, Schneider JS, Adler CH. The neurobiological basis of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 29: 634–650, 2014. doi: 10.1002/mds.25857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TU, Allen M, Purg N, Moutoussis M, Rees G, Dolan RJ. Noradrenaline blockade specifically enhances metacognitive performance. eLife 6: e24901, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotson JR, Boman DR. Memory-contingent saccades and the substantia nigra postulate for essential blepharospasm Brain 114, Pt 1A: 295–307, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-T, Georgiev D, Foltynie T, Limousin P, Speekenbrink M, Jahanshahi M. Different effects of dopaminergic medication on perceptual decision-making in Parkinson’s disease as a function of task difficulty and speed-accuracy instructions. Neuropsychologia 75: 577–587, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah HA, Berardelli A, Comella C, Defazio G, Delong MR, Factor S, Galpern WR, Hallett M, Ludlow CL, Perlmutter JS, Rosen AR; Dystonia Coalition Investigators . The focal dystonias: current views and challenges for future research. Mov Disord 28: 926–943, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mds.25567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: the dual syndrome hypothesis. Neurodegener Dis 11: 79–92, 2013. doi: 10.1159/000341998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton BJ, Mangels JA, Squire LR. A neostriatal habit learning system in humans. Science 273: 1399–1402, 1996. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Summerfield JJ, Hassabis D, Maguire EA. Tracking the emergence of conceptual knowledge during human decision making. Neuron 63: 889–901, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper DJ, Parra V, Aerts S, Okun MS, Kluger BM. Nonmotor manifestations of dystonia: a systematic review. Mov Disord 26: 1206–1217, 2011. doi: 10.1002/mds.23709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lak A, Nomoto K, Keramati M, Sakagami M, Kepecs A. Midbrain dopamine neurons signal belief in choice accuracy during a perceptual decision. Curr Biol 27: 821–832, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Seo M, Dal Monte O, Averbeck BB. Injection of a dopamine type 2 receptor antagonist into the dorsal striatum disrupts choices driven by previous outcomes, but not perceptual inference. J Neurosci 35: 6298–6306, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4561-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PA, MacDonald AA, Seergobin KN, Tamjeedi R, Ganjavi H, Provost JS, Monchi O. The effect of dopamine therapy on ventral and dorsal striatum-mediated cognition in Parkinson’s disease: support from functional MRI. Brain 134: 1447–1463, 2011. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller ML, Bohnen NI. Cholinergic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13: 377, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, Calabro F, Luna B. The role of experience in adolescent cognitive development: Integration of executive, memory, and mesolimbic systems. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 70: 46–58, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano-Saito A, Cisek P, Perna AS, Shirdel FZ, Benkelfat C, Leyton M, Dagher A. From anticipation to action, the role of dopamine in perceptual decision making: an fMRI-tyrosine depletion study. J Neurophysiol 108: 501–512, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00592.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neychev VK, Gross RE, Lehéricy S, Hess EJ, Jinnah HA. The functional neuroanatomy of dystonia. Neurobiol Dis 42: 185–201, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto K, Schultz W, Watanabe T, Sakagami M. Temporally extended dopamine responses to perceptually demanding reward-predictive stimuli. J Neurosci 30: 10692–10702, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4828-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM. Cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: the role of frontostriatal circuitry. Neuroscientist 10: 525–537, 2004. doi: 10.1177/1073858404266776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]