Abstract

Hospitals have an opportunity to dramatically improve the quality of care provided to victims of elder mistreatment, which is common and has serious consequences. An Emergency Department (ED) visit for acute injury or illness may be the only time a victimized older adult leaves their home, and hospitals have a wide range of resources available to respond. EDs already play an important role in the identification of and intervention for other types of family violence, including child abuse and intimate partner violence among younger adults. To date, few interventions to prevent or stop elder abuse, neglect, or exploitation have been described, with none focused in an acute care hospital. Successful hospital-based interventions in child abuse and intimate partner violence may serve as models for approaches to address elder mistreatment. We describe the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team, an innovative, multi-disciplinary ED-based intervention for elder mistreatment victims.

Keywords: elder abuse, emergency department, intervention

Problem Definition

Hospitals have an opportunity to dramatically improve the quality of care provided to a particularly vulnerable population, victims of elder mistreatment. As defined in the 2014 Elder Justice Roadmap, a report prepared by a large, multi-disciplinary team of stakeholders inside and outside the US government, elder mistreatment is: physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, as well as neglect, abandonment, and financial exploitation of an older person by another person or entity that occurs in any setting (e.g. home, community, or facility) either in a relationship where there is an expectation of trust and/or when an older person is targeted based on age or disability.1 This mistreatment is surprisingly common, affecting 5–10% of community-dwelling older adults each year.1–6 Medical consequences of this abuse are serious, with victims having increased depression,6–8 as well as dramatically higher mortality.6,9,10 Despite its frequency and severity, elder mistreatment is rarely identified, with as few as 1 in 24 cases reported to the authorities.3 Few programs to prevent or stop elder abuse have been examined in the peer-reviewed literature,11–15 with even fewer demonstrating an a convincing impact on important outcomes.16,17 Notably, these interventions were conducted in various community and institutional settings, with none focused in an acute care hospital.

A hospital emergency department (ED) visit provides a unique potential opportunity to identify elder abuse and to initiate intervention.18–21 A visit to the ED for acute injury or illness may be the only time a victimized older adult leaves his or her home.21 Mistreatment victims are typically socially isolated and are less likely to seek outpatient medical care.18–21 In addition, an ED and hospital have multiple members of the care team who can contribute to identification of mistreatment during an evaluation that is typically prolonged.21 The ED also has access to a wide range of resources available 24/7 to respond.21 The ED already plays an important role in the identification of and intervention for other types of family violence, including child abuse22,23 and intimate partner violence among younger adults.24,25 Despite this, ED providers seldom identify or report elder mistreatment.26–28 Though not well understood, many reasons likely contribute to this, including time constraints, inadequate training and experience, and concern about involvement with the legal system.28,29 Improving detection of and intervention for elder mistreatment are opportunities to provide high-quality impactful care and increase the safety of these vulnerable patients. In this article, we build on ideas initially suggested by Rosen et al.21 We examine as models hospital-based interventions for other types of family violence, and we describe in detail an innovative, multi-disciplinary ED-based intervention for elder abuse victims.

Models for Intervention

Models exist to improve intervention for victims of elder mistreatment in the ED/hospital which capitalize on the multi-disciplinary resources already available in many large medical centers. Hospital-based child protection teams were developed more than 50 years ago in response to the recognition that cases of child abuse are often complex, represent high-stakes medical and social care, and frequently require time-consuming forensic evaluation and contact with appropriate authorities.22 Members of these multi-disciplinary teams work together to maximize the quality and coordination of care of the maltreated child, with the aim of improving child health outcomes. By virtue of this coordinated care, these teams allow the ED and hospital clinical providers to return to the care of other emergent patients. Though only limited research has been conducted to rigorously evaluate their effectiveness,22 experts believe that they have a significant impact on care.22 They have been shown to significantly increase the community services obtained by the patient and family.23 Additionally, one study found that institutions with established child protection teams were more likely than others to identify and manage a large number of child abuse or neglect cases and more commonly had complete documentation, were able to track outcomes, and provided follow up care for child abuse and neglect victims.30

Specialized multi-disciplinary programs to intervene for victims of intimate partner violence have also been developed.24 Though interventions have differed in design and scope, and not all have been successful,31–33 some have shown decreased re-victimization rates,34 increased use of community and hospital resources, increased use of domestic violence shelters and shelter counseling,35 increased willingness to leave abusive relationships, and improved quality of life.36 Additionally, sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs have been developed in many EDs to provide medical care, forensic evaluation, and counseling 24/7 to victims of sexual assault.37–41 SANE nurses are trained to conduct specialized medical evaluations, collect forensic evidence using a legally-sanctioned kit, provide emotional support, and advocate for prosecution of sexual assault.39 These nurses are typically called in from home when a victim presents to the ED. Their evaluation and exam may take multiple hours, and, typically, SANE nurses must remain in the patient’s room for the entire forensic portion to preserve chain of custody for evidence collected. SANE programs have reduced the burden on ED providers, who would otherwise be responsible for providing care to these victims, which can be very time-consuming and challenging. Also, though limited research exists, available data suggests that SANE programs have been effective in providing medical care and psychological support for victims of sexual assault while increasing the quality of forensic evidence.39 In many settings, these SANE providers have been integrated into multi-disciplinary sexual assault response teams.42

Approach

Using these models and our own experience, we have developed and launched an innovative, ED-based multi-disciplinary Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Our hospital is a large urban, academic medical center that treats over 90,000 patients each year, of whom 30% are ≥ 60 years old. Our ED focuses on using innovation to optimize care for older adults. Our ED/hospital is a Level I trauma center, a regional burn center, and has a designated in-patient unit for the Acute Care of the Elderly.

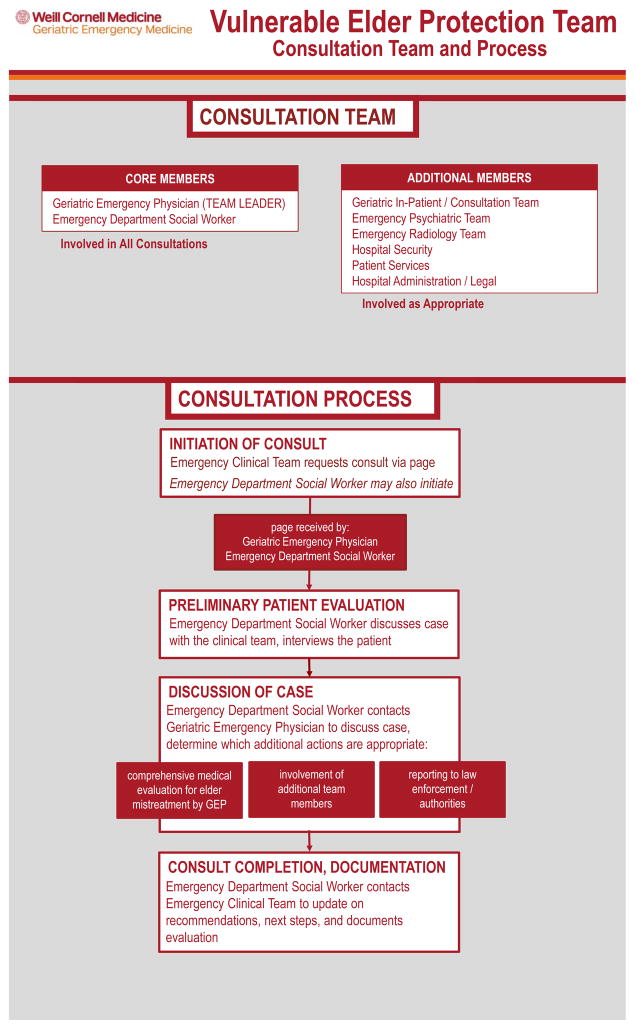

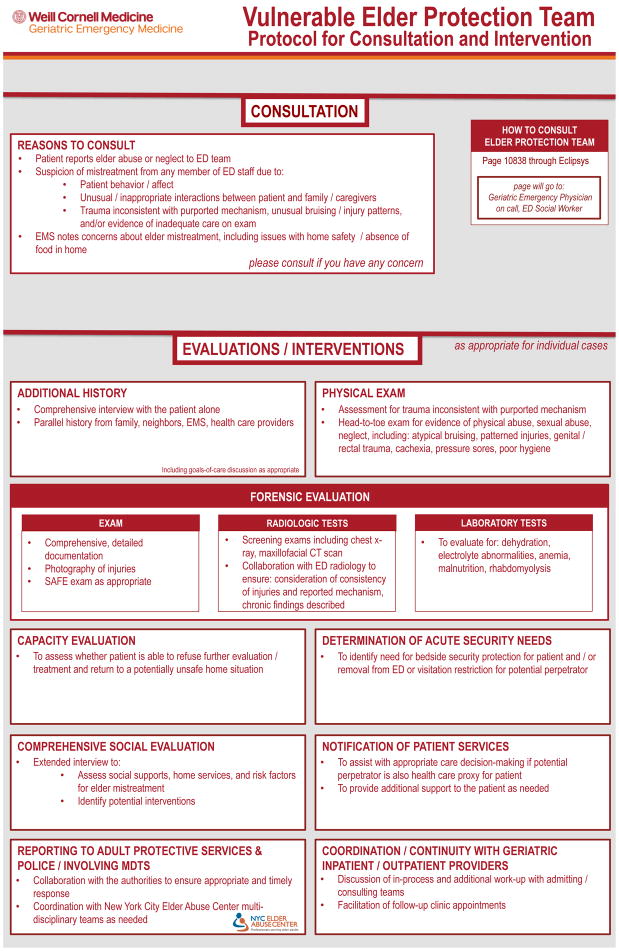

VEPT is a consultation service available 24/7 to improve identification, comprehensive assessment, and treatment for potential victims of elder abuse or neglect. Figures 1 and 2 provide an overview of the current VEPT process and protocol. The design of our intervention takes advantage of the availability of a broad range of resources in a large, urban ED at all times. We are also mindful of the importance to ED providers that a consultation service be available to assist them urgently in the middle of the night.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Activating the VEPT

We have trained all ED providers on how to recognize signs of elder mistreatment. This includes education on identifying high-risk patients using indicators within the medical history, observation of the interactions with caregivers, and physical signs potentially suspicious for mistreatment. An online version of this training has been incorporated into orientation for all new ED providers. Any provider can activate the VEPT via a single page/telephone call. This allows the ED provider to return to the care of other critically-ill patients while the multi-disciplinary VEPT completes the often time-consuming, complex assessment of the potential mistreatment victim. We anticipate that, by significantly reducing the burden on ED providers, the presence of the VEPT will increase identification and reporting of elder mistreatment.

Social Worker Performs Initial Bedside Assessment

For all cases, when the VEPT is activated, the ED social worker on duty responds initially and assesses the patient. ED social workers are already available in our department 24 hours a day, similar to many large EDs, which have recognized their value to the care team,43 particularly for older patients.44 In preparation for the launch of the VEPT, all ED social workers have received additional training in elder mistreatment assessment and intervention. In addition to their routine geriatric evaluation, the VEPT social worker explores in detail the specific concerns expressed by the referring ED provider and will formally screen for mistreatment, including neglect, psychological abuse, financial exploitation, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. If suspicion for mistreatment persists after this initial assessment, the social worker may perform a comprehensive social evaluation, focusing on functional status, living arrangements, financial status, social support/resources, emotional/psychological status, and stressors. A list of questions for this screening and structured interview guide for the comprehensive social evaluation has been developed, and we are currently validating it. A patient with the capacity to make the decision may refuse evaluation by the VEPT or any component of the assessment.

The VEPT social worker also separately interviews the potential perpetrator and/or caregiver.45,46 The purpose of this interview is to identify important discrepancies from the patient’s history, and, for potential perpetrators who are also caregivers, to assess how familiar he/she is with an older adult’s routine medications and necessary medical care. The interview is conducted in a nonjudgmental, non-threatening, and supportive manner. It may also explore the perpetrator’s risk for mistreatment, including: whether any important changes or recent stresses have occurred in the household, whether caring for the older adult is burdensome, the potential perpetrator’s other dependents and responsibilities, and whether any home help services or respite services have been made available. Additionally, the social worker gathers collateral information from other sources when possible.

Collaborative Discussion with the On-Call Medical Provider

After their assessment, the social worker contacts the on-call VEPT medical provider to collaboratively discuss next steps and whether other team members need to become involved. This on-call responsibility is currently shared by three emergency physicians with additional geriatrics and forensic training. The on-call schedule takes into account their other clinical responsibilities. We plan in the future to hire geriatric nurse practitioners to take the on-call responsibilities. The total full-time equivalent devoted to this role at launch is 75% including all participants, but we anticipate that this will change.

Medical Provider Performs Comprehensive Medical and Forensic Assessment

After discussing the case with the ED social worker, the VEPT medical provider is available, when appropriate, to come to the ED to conduct a comprehensive medical and forensic assessment of the patient that the ED medical providers may not have the time and/or the skills to perform. This assessment includes obtaining supplemental history and conducting a head-to-toe physical examination. The VEPT medical provider conducts a comprehensive interview with the patient alone, focusing on the reason for the current ED visit and past medical history/medical status. He/she also performs a formal cognitive assessment. This assessment may include the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)47 and/or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).48 The MoCA is used if the patient has no history of cognitive impairment and there is low suspicion of significant impairment, as this test is more sensitive for mild impairment.49 In other cases, we administer the MMSE. When appropriate, the VEPT medical provider acquires parallel history from family, friends, neighbors, caregivers, and out-patient health care providers. The physical exam includes assessment for trauma inconsistent with purported mechanism and any evidence7 of physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect, including: atypical bruising, patterned injuries, genital/rectal trauma, cachexia, pressure sores, or poor hygiene. The VEPT medical provider comprehensively documents all findings, which may be critical for future legal processes but is often incomplete and inadequate in current practice, even for child abuse.50,51 Additionally, the VEPT medical provider photographs injuries and conducts a sexual assault forensic exam when appropriate. All VEPT providers have received appropriate needed training to perform sexual assault forensic exams. The VEPT medical provider initiates radiographic tests for occult or chronic injuries and collaborate with the ED radiologist to ensure consistency of injuries and reported mechanism as well.52,53 He/she may also initiate laboratory testing to evaluate for: dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, anemia, malnutrition, or rhabdomyolysis.54 This initial evaluation by the medical provider typically takes 30–60 minutes, but additional case coordination, with phone calls and follow up/interpretation of test results may be needed during the next several hours.

Additional Team Members Contribute as Needed

For many potential elder mistreatment victims with complex cases, additional VEPT team members contribute when necessary. For example, a patient may decline VEPT assessment or request discharge into an unsafe environment. If his/her capacity to make these decisions is unclear, as is common among older adults, an ED psychiatrist assesses them and provides guidance. In some cases, hospital security may need to become involved to protect the patient and/or remove a potential perpetrator from the ED or restrict visitation. If a potential perpetrator is the patient’s health care proxy or surrogate decision-maker, hospital ethics and legal services may need to become involved to help guide appropriate care decisions and even guardianship. These professionals have received additional training, and the VEPT design takes advantage of the fact that they are all currently available in our hospital 24/7.

Integration with In-Patient, Out-Patient, and Community Resources

For patients admitted to the hospital, the VEPT connects with the in-patient social workers and medical team to ensure appropriate follow-up and care planning. For patients discharged, the VEPT utilizes out-patient resources including early appointments in our multi-disciplinary geriatrics clinic and, for patients with mental health issues, visits from our hospital’s mobile crisis team. We may also consider elder abuse shelter as a discharge option. The VEPT has formed partnerships with other community resources through our participation in the New York City Elder Abuse Center (www.nyceac.com) and refers patients and caregivers, when appropriate, to programs within the New York City Department for the Aging and other agencies. We will also involve Adult Protective Services (APS) and other authorities when necessary. Opportunities exist to use the VEPT itself as a community resource, and we are exploring protocols for APS and emergency medical services to identify and refer to our ED older adults who are in unsafe situation and may benefit from immediate evaluation.

Program Administrator Provides Feedback, Support, and Coordination

A full-time program administrator (PA), who is also a licensed social worker, supports and assists the team. The PA gives and solicits feedback to/from ED providers who have consulted the VEPT, updating them on case status and identifying any issues with the VEPT processes. The PA tracks cases and provide support to in-patient social workers by suggesting intervention strategies, available resources, and disposition options. The PA also coordinates regular multi-disciplinary case review meetings with VEPT program leadership and manages the medical provider on-call schedule. Comprehensive protocols of all aspects of VEPT operations are available as an online supplement and at xxx.com. The presence of a full-time PA also allows for short and long-term patient tracking and program evaluation.

Next Steps/Planned Evaluation

We launched the VEPT program in April 2017 after comprehensive training and plan to use several strategies to evaluate and measure its success. We have already begun to track closely the number of referrals and completed consultations, which types of providers are referring, as well as the characteristics and circumstances of potential victims and perpetrators. This will be critical for quantifying the human resources needed for the program and identifying when and for whom additional training is required. We will hold regular meetings to review individual cases to ensure that the care the VEPT is providing is optimal and standardized. We will also conduct and analyze focus groups and surveys of participating ED providers to improve understanding of their experiences interacting with the VEPT, and the findings will inform changes to our process. The impact of the program will be measured by tracking the short-term and long-term mistreatment-related as well as medical, mental health, functional, psychosocial, and legal outcomes of the vulnerable ED patients for whom we provide care. Selected key outcomes we plan to examine as well as anticipated data sources to track these are described in Table 1. Notably, we have included perpetrator prosecution as a relevant legal outcome. Many victims of elder mistreatment want help/support for the perpetrator and do not want to pursue prosecution.16,55,56 Also, however, many elder mistreatment perpetrators are not prosecuted because of insufficient evidence gathered by acute care medical providers,57 particularly for patients with cognitive impairment. Therefore, while not relevant for every patient, we think that it is an important outcome to examine overall when evaluating our program. Given the heterogeneity of victim circumstances and relevant outcomes, we also plan to employ innovative measurement strategies including goal-attainment scaling58 to accurately measure the program’s impact.

Table 1.

Selected Outcomes to Examine and Anticipated Data Sources to Evaluate Impact of Vulnerable Elder Protection Team

| Outcomes | Potential Data Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Short-Term | Long-Term | |

| medical | connection to primary care provider, medication adherence, pain control, management of chronic conditions | mortality, ED visits, hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility placement, connection to primary care provider, medication adherence, pain control, management of chronic conditions | hospital and outpatient medical records, collaboration with skilled nursing facilities, follow-up with patient/other reporters |

| functional | independence in activities of daily living/instrumental activities of daily living, ambulation status | independence in activities of daily living/instrumental activities of daily living, ambulation status | hospital and outpatient medical records, collaboration with skilled nursing facilities, collaboration with community service providers through NYCEAC, follow-up with patient/other reporters |

| psychosocial | depression, anxiety, social isolation, quality of life | depression, anxiety, social isolation, quality of life | hospital and outpatient medical records, collaboration with skilled nursing facilities, collaboration with community service providers through NYCEAC, follow-up with patient/other reporters |

| legal | reporting to Adult Protective Services, reporting to police, complaint filing to Department of Health about skilled nursing facility, securing order of protection | case substantiation by Adult Protective Services, perpetrator prosecution | collaboration with police, district attorney’s offices through NYCEAC,, follow-up with patient/other reporters |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support:

This project has been supported by a grant from The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation and by a Change AGEnts Grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Dr. Rosen’s participation was supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant (R03 AG048109) and by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders in Aging Career Development Award (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Rosen is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Dr. Lachs’ participation was supported by a mentoring award in patient-oriented research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG022399).

References

- 1.National Center for Elder Abuse. [Accessed August 25, 2017];The Elder Justice Roadmap: A Stakeholder Initiative to Respond to an Emerging Health, Justice, Financial, and Social Crisis. at https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download)

- 2.Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed August 25, 2017];Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys. 2012 at http://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf)

- 4.Acierno R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:292–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet. 2004;364:1263–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachs MS, Pillemer KA. Elder Abuse. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1947–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs LM. Understanding the medical markers of elder abuse and neglect: physical examination findings. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30:687–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouton CP, et al. Psychosocial effects of physical and verbal abuse in postmenopausal women. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:206–13. doi: 10.1370/afm.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachs MS, et al. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA. 1998;280:428–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong XQ, et al. Elder abuse and mortality: the role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology. 2011;57:549–58. doi: 10.1159/000321881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker PR, et al. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 16;(8):CD010321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010321.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong XQ. Elder abuse: systematic review and implications for practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1214–38. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillemer K, et al. Practitioners’ views on elder mistreatment research priorities: recommendations from a research-to-practice consensus conference. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2011;23:115–26. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.558777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillemer K, et al. Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 2):S194–205. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ploeg J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2009;21:187–210. doi: 10.1080/08946560902997181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirey JA, et al. PROTECT: A pilot program to integrate mental health treatment into elder abuse services for older women. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2015;27:438–53. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1088422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirey JA, et al. Feasibility of integrating mental health screening and services into routine elder abuse practice to improve client outcomes. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2015;27:254–69. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1008086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between elder abuse and use of ED: findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:693–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachs MS, et al. ED use by older victims of family violence. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:448–54. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platts-Mills TF, et al. Emergency physician identification of a cluster of elder abuse in nursing home residents. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen T, et al. Identifying elder abuse in the emergency department: Toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:378–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kistin CJ, et al. Factors that influence the effectiveness of child protection teams. Pediatrics. 2010;126:94–100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochstadt NJ, Harwicke NJ. How effective is the multidisciplinary approach? A follow-up study Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:365–72. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choo EK, et al. Systematic Review of ED-based intimate partner violence intervention research. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:1037–42. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.10.27586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes KV, et al. Brief motivational intervention for intimate partner violence and heavy drinking in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:466–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The 2004 survey of state adult protective services: abuse of adults 60 years of age and older. National Center on Elder Abuse; 2004. [Accessed August 25, 2017]. at https://ncea.acl.gov/resources/docs/archive/2004-Survey-St-Audit-APS-Abuse-18plus-2007.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blakely BE, Dolon R. Another look at the helpfulness of occupational groups in the discovery of elder abuse and neglect. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2003;13:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans CS, et al. Diagnosis of elder abuse in U.S. emergency departments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:91–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones JS, et al. Elder mistreatment: national survey of emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:473–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tien IBH, Reece RM. What is the System of Care for Abused and Neglected Children in Children’s Institutions? Pediatrics. 2002;110:1226–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koziol-McLain JGN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief emergency department intimate partner violence screening intervention. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:413–23. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFarlane JSK, Wiist W. An evaluation of interventions to decrease intimate partner violence to pregnant women. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:443–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotnick CCN, Parker D. An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyman K. Impact of Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy: A Longitudinal, Randomized Trial. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muelleman RLFK. Effects of an emergency department-based advocacy program for battered women on community resource utilization. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:62–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacMillan HWC, et al. Screening for IPV in health care settings: a randomized trial. McMaster Violence Against Women Research Group. JAMA. 2009;302:493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor WK. Collecting evidence for sexual assault: the role of the sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(Suppl 1):S91–4. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutson LA. Development of sexual assault nurse examiner programs. Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;37:79–88. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(03)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF. The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs: a review of psychological, medical, legal, and community outcomes. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6:313–29. doi: 10.1177/1524838005280328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houmes BV, Fagan MM, Quintana NM. Establishing a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) program in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:111–21. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLaughlin SA, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a training program for the management of sexual assault in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:489–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greeson MR, Campbell R. Coordinated community efforts to respond to sexual assault: a national study of sexual assault response team implementation. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30:2470–87. doi: 10.1177/0886260514553119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Auerbach C, Mason SE. The value of the presence of social work in emergency departments. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49:314–26. doi: 10.1080/00981380903426772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton C, Ronda L, Hwang U, et al. The evolving role of geriatric emergency department social work in the era of health care reform. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54:849–68. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1087447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breckman RS, Adelman RD. Strategies for helping victims of elder mistreatment. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn MJ, Tomita SK. Springer series on social work. 2. New York: Springer; 1997. Elder abuse and neglect causes, diagnosis, and intervention strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasreddine ZS, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trzepacz PT, et al. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging I. Relationship between the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-mental State Examination for assessment of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:107. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guenther E, et al. Randomized prospective study to evaluate child abuse documentation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:249–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson AM, et al. Let the record speak: medicolegal documentation in cases of child maltreatment. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:181–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen T, et al. Radiologists’ training, experience, and attitudes about elder abuse detection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1210–4. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong NZ, et al. Imaging findings in elder abuse: a role for radiologists in detection. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2017;68:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LoFaso VM, Rosen T. Medical and laboratory indicators of elder abuse and neglect. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30:713–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson SL, Hafemeister TL. How case characteristics differ across four types of elder maltreatment: implications for tailoring interventions to increase victim safety. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33:982–97. doi: 10.1177/0733464812459370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen T, et al. Acute precipitants of physical elder abuse: qualitative analysis of legal records from highly adjudicated cases. J Interpers Violence. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0886260516662305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kogan AC, et al. Developing a tool to improve documentation of physical findings in injured geriatric patients: Insights from experts in multiple disciplines. American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting; May 2017; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burnes D, Lachs MS. The case for individualized goal attainment scaling measurement in elder abuse interventions. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36:116–22. doi: 10.1177/0733464815581486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.