Abstract

Bacteriophage T4 is a natural bio-nanomachine which achieves efficient infection of host cells via cooperative motion of specific three-dimensional protein architectures. The relationships between the protein structures and their dynamic functions have recently been clarified. In this review we summarize the design principles for fabrication of nanomachines using the component proteins of bacteriophage T4 based on these recent advances. We focus on the protein needle known as gp5, which is located at the center of the baseplate at the end of the contractile tail of bacteriophage T4. This protein needle plays a critical role in directly puncturing host cells, and analysis has revealed that it contains a common motif used for cell puncture in other known injection systems, such as T6SS. Our artificial needle based on the β-helical domain of gp5 retains the ability to penetrate cells and can be engineered to deliver various cargos into living cells. Thus, the unique components of bacteriophage T4 and other natural nanomachines have great potential for use as molecular scaffolds in efforts to fabricate new bio-nanomachines.

Keywords: Bacteriophage T4, Gp5, β-Helix, Protein needle, Cell penetration

Introduction

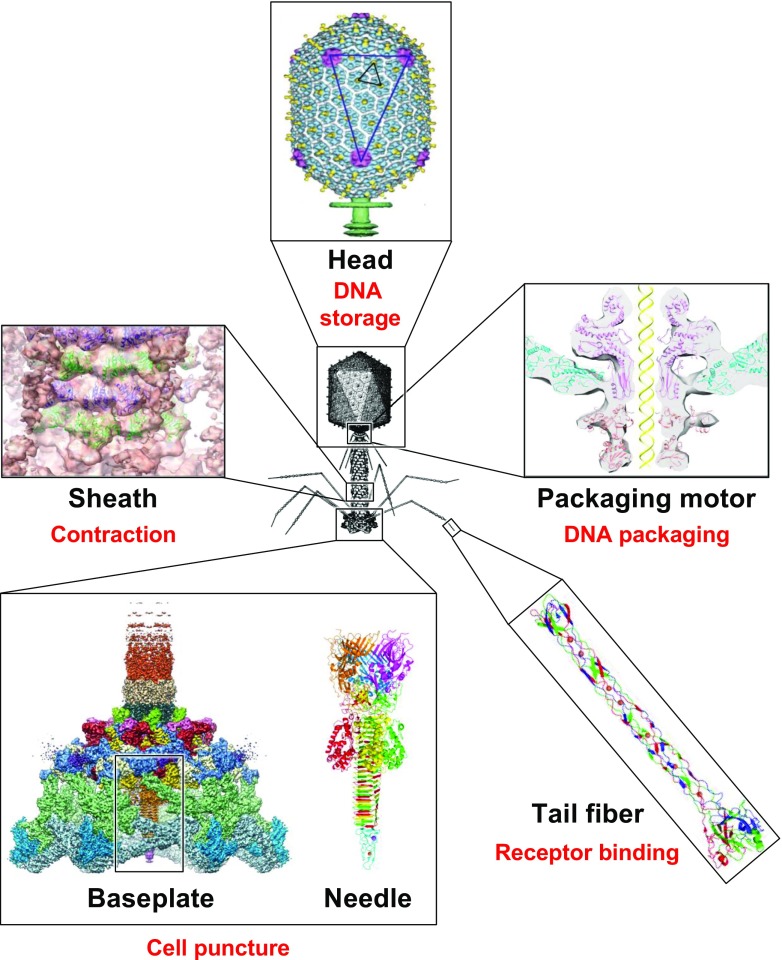

Virus-templated nanomaterials

Viruses are sophisticated supramolecular machines with distinct shapes and sizes that achieve efficient infection of host cells (Rossmann and Rao 2012). Due to their high stability, homogeneity and symmetrical structures, as well as the ability to be easily modified by chemical and genetic modifications, viral assemblies have been widely exploited as templates in efforts to fabricate nanomaterials for diverse applications, including phage display (Wen and Steinmetz 2016), intracellular delivery (Koudelka and Manchester 2010; Ma et al. 2012; Li and Wang 2014; Karimi et al. 2016; Wen and Steinmetz 2016), synthesis of metal nanoparticles (Ueno 2008; Liu et al. 2012; Li and Wang 2014; Wen and Steinmetz 2016), and energy transfer (Ueno 2008; Koudelka and Manchester 2010; Li and Wang 2014; Wen and Steinmetz 2016). The simple viral assemblies from one type of capsid protein that forms part of viruses such as tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), bacteriophage M13, cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) and cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) are widely used for these purposes. Unlike these viruses, tailed bacteriophages are more complicated nanomachines consisting of a variety of unique components. Bacteriophage T4 is one of the most highly studied tailed bacteriophages (Karam et al. 1994; Leiman et al. 2003, 2010; Rossmann et al. 2004; Arisaka et al. 2016), and these studies have revealed that bacteriophage T4 consists of more than 40 component proteins which form various assembly structures, such as the capsid head (Fokine et al. 2004; Rao and Black 2010), the packaging motors (Sun et al. 2007, 2008, 2015), the sheath (Aksyuk et al. 2009), the tail fiber (Bartual et al. 2010; Granell et al. 2017) and the baseplate (Kostyuchenko et al. 2003; Taylor et al. 2016; Yap et al. 2016) (Fig. 1). A cell-puncturing needle is located at the center of the baseplate of bacteriophage T4 (Fig. 1) (Kanamaru et al. 2002). The cooperative structural changes of each component protein enable efficient injection of the phage genome into host cells (Leiman et al. 2003; Rossmann et al. 2004; Leiman et al. 2010; Hu et al. 2015; Arisaka et al. 2016; Taylor et al. 2016). For example, in bacteriophage T4, the tail fiber is involved in receptor binding, the head is involved in DNA storage, the sheath is involved in contraction and the baseplate plays a role in cell puncture. The unique structural properties of the components of bacteriophage T4 have inspired scientists to use them as molecular scaffolds. In this review, we provide an overview of nanomachine construction by chemical and genetic engineering, using the components of bacteriophage T4 (Fig. 2). In particular, we focus on the cell-puncturing needle, which is a common motif in bacteriophages, bacterial secretion systems, bacteriocins and other protein injection systems. Our designed needle, which is based on the structure of the needle of bacteriophage T4, retains the ability to puncture cells and can deliver molecular cargos into living cells. These findings provide insight into future designing of nanomachines based on modification of natural supramolecular assemblies.

Fig. 1.

Bacteriophage T4 with detailed structures of the head, the packaging motor, the sheath, the tail fiber and the baseplate with the needle (adapted from Fokine et al. 2004; Aksyuk et al. 2009; Sun et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2016)

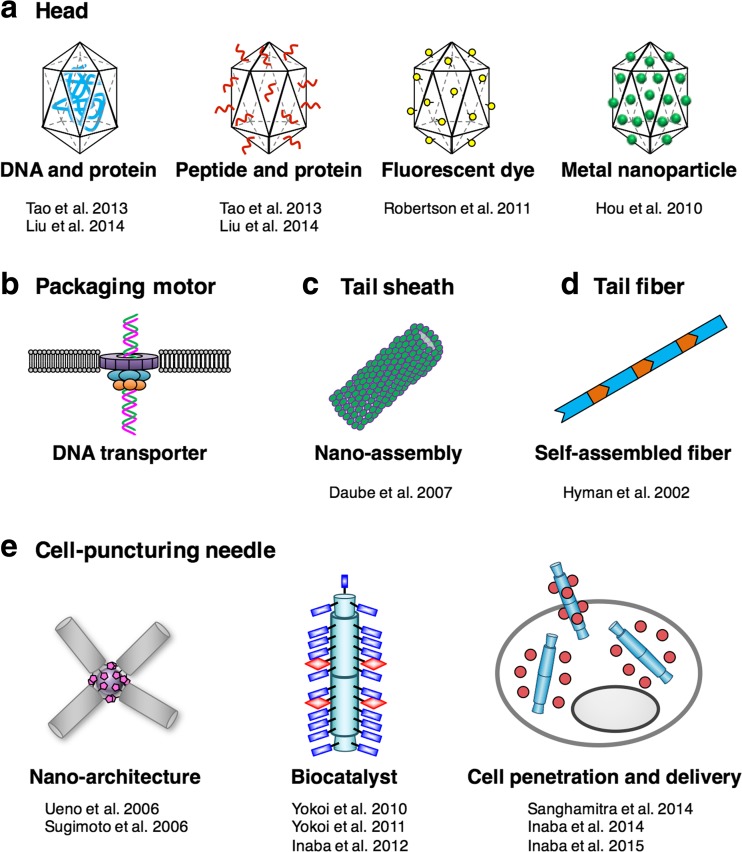

Fig. 2.

Reported and proposed nanomaterials based on the component proteins of bacteriophage T4, by means of chemical and genetic engineering. a Incorporation of DNA and protein into the head and modifications of protein, peptide, fluorescent dye and metal nanoparticles on the surface of the head (Hou et al. 2010; Robertson et al. 2011; Tao et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2014). b A DNA transporter based on the packaging motor which is inserted into lipid bilayers. c Nano-assembled tubes consisting of sheath proteins (Daube et al. 2007). d Self-assembled fiber consisting of tail fiber proteins (Hyman et al. 2002). e Nano-architecture (Sugimoto et al. 2006; Ueno et al. 2006), biocatalyst (Yokoi et al. 2010; Yokoi et al. 2011; Inaba et al. 2012) and cell penetration and intracellular delivery (Inaba et al. 2014b, 2015a; Sanghamitra et al. 2014) using a cell-puncturing needle

Engineering of component proteins of bacteriophage T4

It has been recognized that the component proteins of bacteriophage T4 can be used as scaffolds for the construction of various nanomaterials by chemical and genetic engineering because (1) their individual functions displayed during the infection process (DNA packaging, recognition of host cells, cell penetration) can be harnessed, (2) the self-assembled three-dimensional structures can be isolated in vitro and (3) most of the assembly components are highly stable. In this section, we describe several examples that utilize the head, the DNA packaging motor, the sheath, and the tail fiber, respectively, of bacteriophage T4 for various applications (Fig. 2).

Head

The head of bacteriophage T4 is a 120 × 86-nm icosahedral structure that consists of the major capsid protein gene product (gp) 23*, vertex protein gp24*, highly antigenic outer-capsid protein (Hoc) and small outer capsid protein (Soc) (Fokine et al. 2004; Rao and Black 2010). The head is connected to the DNA packaging motor, as will be described in detail below. The highly symmetric structure and the DNA loading function of the head have been utilized in various applications, such as intracellular delivery of genes and proteins (Tao et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2014), cellular imaging (Robertson et al. 2011), assembly of metal nanoparticles (Hou et al. 2010) and assembly of sensors (Archer and Liu 2009).

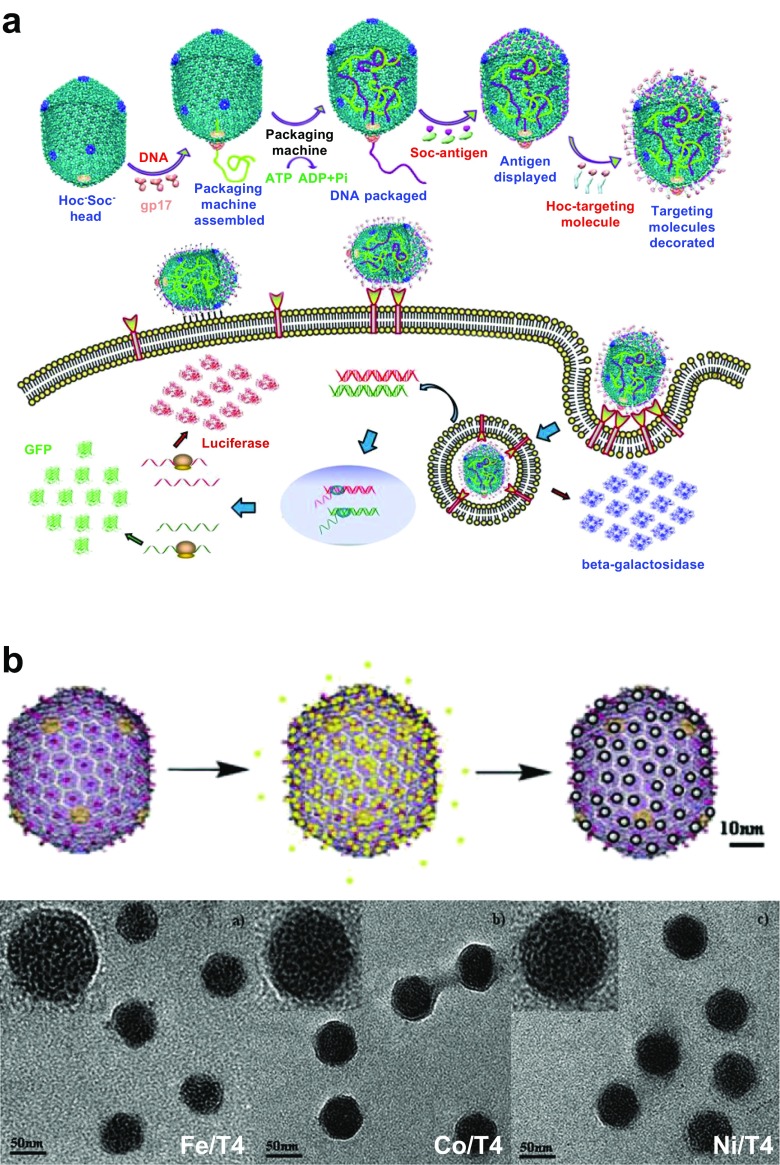

Rao and colleagues engineered the head of bacteriophage T4 to deliver DNA and proteins into mammalian cells (Fig. 3a) (Tao et al. 2013). DNA was incorporated into the head-packaging motor complex which is fueled by ATP, and then Soc- and/or Hoc-fused proteins/peptides were placed on the surface of the head. The modified heads were attached to the cells nonspecifically or by through recognition of a receptor, and the assembly was internalized into mammalian cells by endocytosis. The surface-displayed proteins and incorporated DNA were then released into the cytosol. Using this approach, single or multiple plasmids, long ~ 80-kb ligated DNA or short 2.3-kb PCR-amplified DNA segments were efficiently packaged into the head. The cell penetration peptides (CPPs) and proteins such as β-galactosidase, dendritic cell-specific receptor (DEC)205 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and CD40 ligand (CD40L) were then arrayed on the head. The internalization efficiency of the head of bacteriophage T4 was increased by attaching CPPs. By displaying DEC205mAb and CD40L, the head of bacteriophage T4 could be delivered to the targeted cells which express the respective receptors. β-Galactosidase was delivered to cells with nearly 100% efficiency using the head of bacteriophage T4. The method was applied to deliver F1-V plague vaccine genes or proteins in vivo, which were then found to induce robust antibody activity and cellular immune responses. The results indicate that the head of bacteriophage T4 is useful as a scaffold for intracellular delivery of genes, peptides, and proteins.

Fig. 3.

a Engineering of the head of bacteriophage T4 for delivery of genes and proteins into mammalian cells (adapted from Tao et al. 2013). b Template synthesis of metal nanoparticles on the head of bacteriophage T4 (upper) and transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) images of Fe/T4, Co/T4, and Ni/T4 structures (bottom) (adapted from Hou et al. 2010). HOC Highly antigenic outer-capsid protein, Soc small outer capsid protein, gp gene product, GFP green fluorescent protein, Pi inorganic phosphate

Gao and colleagues utilized the highly symmetric and highly stable head of bacteriophage T4 as a scaffold to construct three-dimensional metal nanoparticle arrays (Fig. 3b) (Hou et al. 2010). By simple incubation of the head of bacteriophage T4 with Pt, Rh and Pd chlorides at neutral pH for several cycles and subsequent reduction by dimethylaminoborane (DMAB), the metal nanoparticles (diameter 3.0–4.5 nm) became localized on the head of bacteriophage T4. In this assembly, Cys and Met on the surface of the head of bacteriophage T4 act as S-donor ligands to form complexes with the metal ions for nucleation. The electrocatalytic activity of the Pt, Rh and Pd assembly was enhanced by using the head of bacteriophage T4 as a template. Fe, Co, and Ni nanoparticles were assembled on the head of bacteriophage T4 using a similar method, via coordination of the carboxylate groups on the exterior surfaces in the pH range of 8–9. By investigating the magnetic properties of the resultant metal nanoparticle–T4 head complexes, the Ni/T4 head was found to have superparamagnetic characteristics and the Fe/T4 and Co/T4 heads were found to exhibit ferromagnetic behavior.

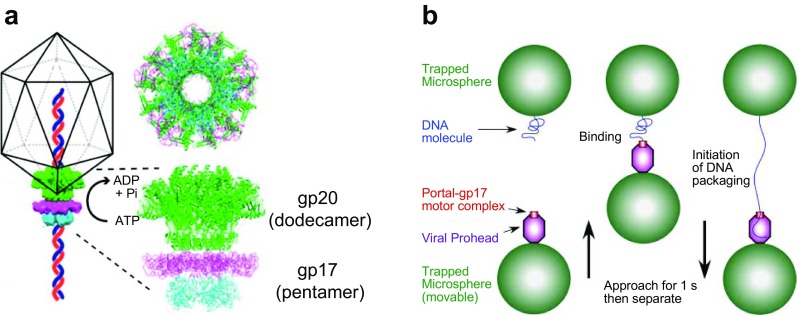

Packaging motor

The DNA packaging motor of bacteriophage T4, a pentamer of gp17 (large terminase protein) assembled on a dodecamer of gp20, serves to translocate DNA into the bacteriophage T4 head via an ATP-driven mechanism (Fig. 4a) (Sun et al. 2007, 2008, 2015). The purified gp17 possesses DNA packaging activity in vitro (Rao and Black 1988). Single molecule analysis using gp17 and the head showed that the packaging motor is among the fastest (~ 2000 bp/s) and most powerful (~ 5000 kW/m3) viral packaging motors reported to date (Fig. 4b) (Fuller et al. 2007). The packaging dynamics of the motor have been investigated in detail by Rao and colleagues (Fuller et al. 2007; Kottadiel et al. 2012; Migliori et al. 2014; Vafabakhsh et al. 2014). Mutagenesis studies have identified the important amino acid residues of gp17 for the DNA packaging activity (Kondabagil et al. 2014; Migliori et al. 2014). Thus, by understanding the detailed structure–function relationships of gp17, it is expected that the engineered gp17 would be inserted into lipid bilayers to translocate DNA, as reported by using the connector protein of the bacteriophage phi29 DNA packaging motor (Wendell et al. 2009).

Fig. 4.

a The DNA packaging motor assembled at the portal vertex of the head of bacteriophage T4 (adapted from Kottadiel et al. 2012). Schematic is not to scale. b Single DNA molecule packaging using an optical tweezer (adapted from Fuller et al. 2007). Copyright (2007) National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C.

Sheath

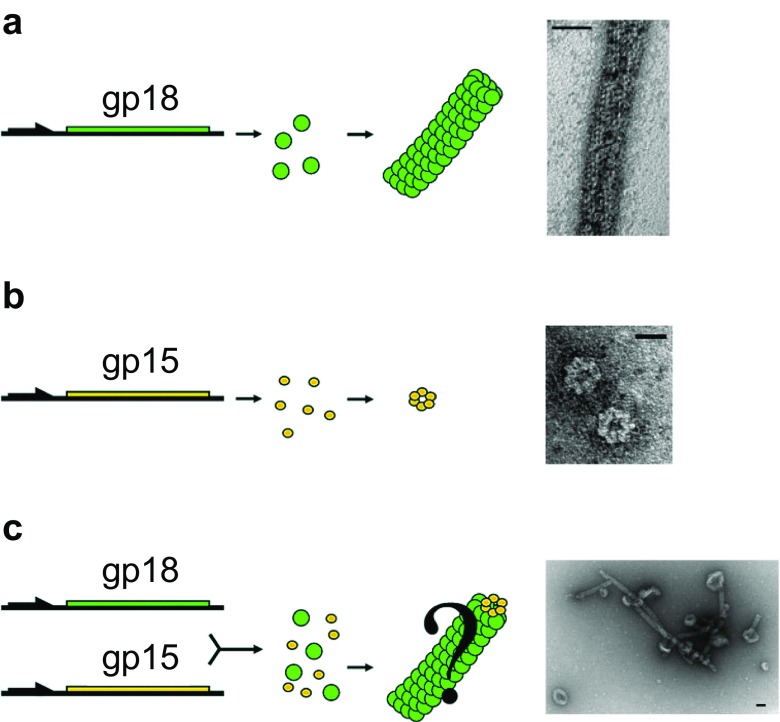

The tail sheath of bacteriophage T4 is composed of 138 copies of gp18 and surrounds the tail tube (Aksyuk et al. 2009). The sheath undergoes contraction during infection to drive the tail tube through the outer membrane. Chemical and genetic modifications of gp18 have been achieved to study the structure and the conformational changes which occur during contraction (Takeda et al. 1990; Efimov et al. 2002). Since gp18 is known to self-assemble to form tubular structures called polysheaths in the absence of the baseplate or the tail tube (Moody 1967), Daube et al. (2007) utilized the self-assembling property to create nano-architectures. In this study, gp18 was co-assembled with gp15, which is a capping protein of the tail. Gp18 with a streptavidin-binding tag and gp15 with a (His)6 tag individually form polysheaths and hexameric ring assemblies, respectively (Fig. 5a, b). Co-assembly of gp18 and gp15 resulted in the formation of doughnut-shaped structures with an outer diameter of 50 nm and a thickness of 20 nm (Fig. 5c). The thickness is similar to that of gp18 polysheaths, suggesting that the nano-doughnut is mainly composed of gp18 polysheaths and formed by incorporation of gp15.

Fig. 5.

Synthesis and assembly of gp18 polysheath (a) and gp15 hexameric rings (b) and co-assembly of gp18 and gp15 to form a nano-doughnut (c) (adapted from Daube et al. 2007). Scale bars of the TEM images: a 20 nm, b 10 nm, c 40 nm

Tail fibers

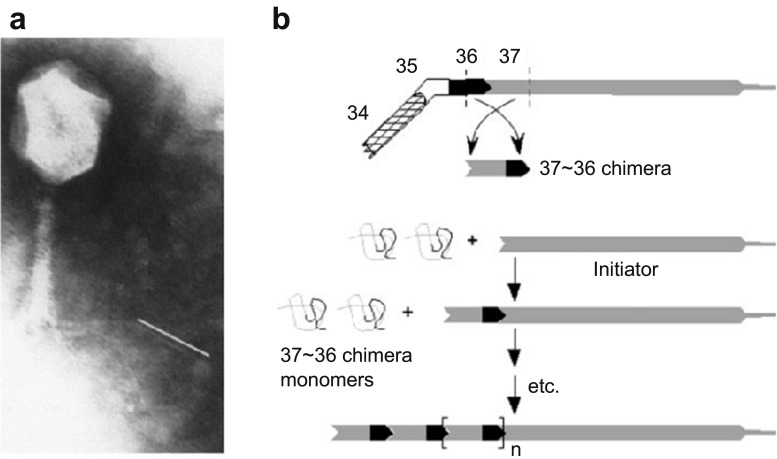

The long tail fibers (3 × 160 nm) of bacteriophage T4 are responsible for the initial interactions with receptor molecules on host cells (Karam et al. 1994; Leiman et al. 2003, 2010). The tail fibers are composed of gp34, gp35, gp36 and gp37, which self-assemble to form proximal and 70-nm distal half-fiber segments. The crystal structures of the C-terminal region of gp34 (residues 744–1289) and the tip of gp37 (residues 785–1026) have been reported (Bartual et al. 2010; Granell et al. 2017). Hyman et al. proposed the construction of mesoscale structures by using the self-assembly domains of the tail fibers. As a first step, a partial sequence of gp37 of bacteriophage T4 was deleted to construct a mutated phage with short tail fibers, without affecting the overall structure and function of the phage (Fig. 6a) (Hyman et al. 2002). By inserting the 15-amino acid epitope sequences into the deleted region of the mutated phage, the epitope on the gp37 of the phage was provided with the ability to bind to the antibody. These results indicate that deletions and insertions can be made to a tail fiber without disrupting the integrity of the matured phage structures. Based on these results, the authors proposed constructing chimeric proteins composed of the gp37 binding domain of gp36 joined by a central rod domain to the gp36 binding end of gp37 to achieve formation of homo-polymeric fibers (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Engineering of tail fibers of bacteriophage T4 (adapted from Hyman et al. 2002). a Electron micrograph of bacteriophage T4 with short tail fibers. The white line next to the tail fiber indicates the length of a wild-type tail fiber. b Concept for forming a protein fiber based on chimera proteins of gp36 and gp37. Copyright (2002) National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C.

Protein needle motifs for cell penetration

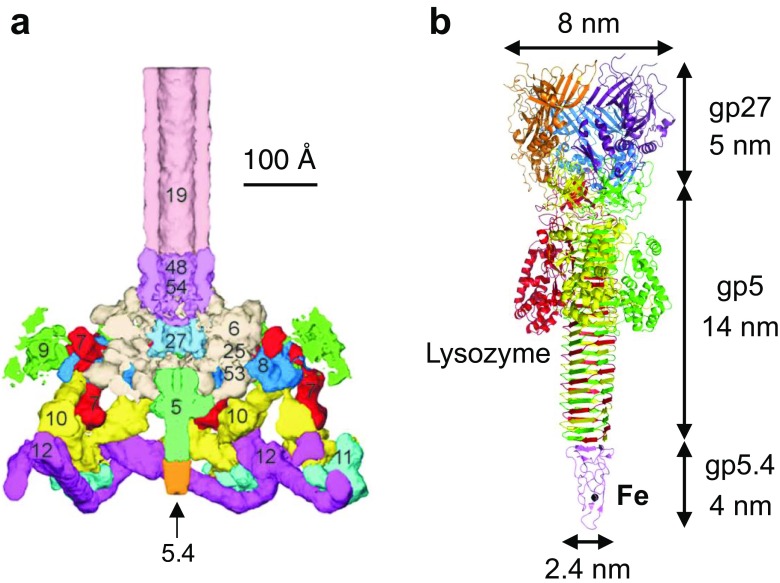

The gp27–gp5 proteins which are located at the center of the baseplate of bacteriophage T4 form a cell-puncturing needle to penetrate the outer membrane of Escherichia coli (Fig. 7a) (Kanamaru et al. 2002, 2005; Leiman et al. 2003; Rossmann et al. 2004). The gp27 trimer forms a 5-nm-long hollow cylinder, and the gp5 trimer forms a 14-nm-long needle to provide a “torch handle” structure (Fig. 7b). The C-terminal end of (gp5)3 consists of a robust needle domain formed of a triple-stranded β-helix that in turn is formed by the repeat sequence VXGXXXXX (Kanamaru et al. 2002). The structure of gp5.4 has recently been reported. This protein provides a tip domain located at the terminal of gp5 (Fig. 7b) (Shneider et al. 2013). During infection, gp5.4 and the β-helix domain of the C-terminal of gp5 directly attach to the host cell membrane and puncture it.

Fig. 7.

a Baseplate of bacteriophage T4 (Kostyuchenko et al. 2003), b gp5–gp27–gp5.4 (combined from PDB IDs: 1 K28 and 4KU0) (Kanamaru et al. 2002). Each color represents a different monomer

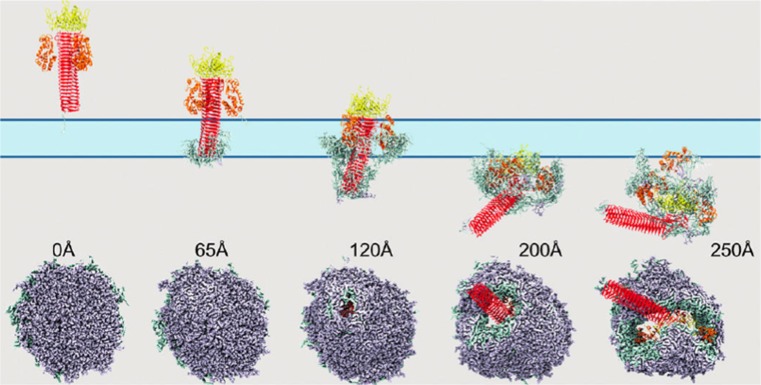

The importance of the β-helix of gp5 for the membrane puncturing function has been investigated using several different methods. Using molecular dynamics simulations and finite element simulations, Buehler and colleagues demonstrated that the mechanical stiffness of the triple-stranded β-helix of gp5 is greater than that of other protein motifs, such as a single-stranded β-helix and a cellular membrane, indicating that the β-helix of gp5 is a suitable structure for cell penetration (Keten et al. 2009, 2011). Kitao and colleagues simulated the penetration of gp5 into a lipid bilayer comprised of dioleyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine (DOPE) (Nishima et al. 2011). The molecular dynamics simulation was achieved by applying force to the top of gp5 in an effort to mimic the effect of the force produced by the sheath of bacteriophage T4 (Fig. 8). This simulation showed that the β-helix of gp5 (1) makes a hole in the membrane by a screw motion and (2) serves to move the lipids upward by strong charge interactions with the charged side chains on the surface of the β-helix. These results suggest that the structure of gp5 is optimized for membrane penetration.

Fig. 8.

Side view (top) and bottom view (bottom) snapshots from the simulation of membrane penetration of gp5 (adapted from Nishima et al. 2011). The zone in light blue shows the initial position of the membrane

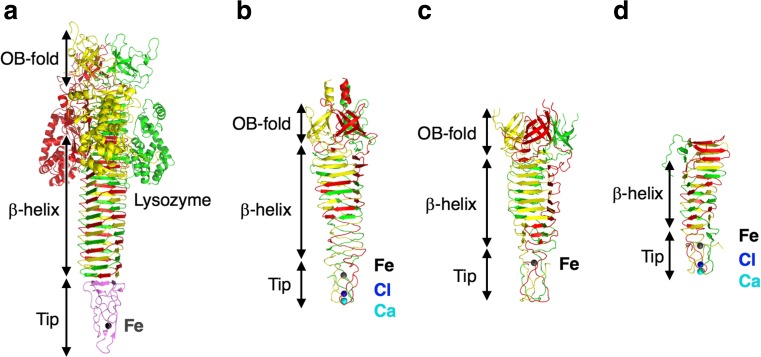

Recent structural analyses indicate that protein needles are common motifs for membrane puncture in several tailed phages and bacterial secretion systems, as summarized in Table 1 (Fokine and Rossmann 2014; Brackmann et al. 2017). The tailed phages (Caudovirales) are classified into three families, namely Myoviridae, Podoviridae and Siphoviridae, based on tail morphology (Xu and Xiang 2017). Myoviridae phages (e.g. T4, P2, ϕ92, Mu) possess a common membrane-puncturing needle domain consisting of an N-terminal oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB-fold) domain, a β-helix domain and a C-terminal tip domain (Fig. 9) (Kanamaru et al. 2002; Yamashita et al. 2011; Browning et al. 2012; Harada et al. 2013). The attachment of the needles to the host cell is initiated by the attachment of the C-terminal tip domains. In gp5.4 of bacteriophage T4, the tip is stabilized by coordination of three His residues to an Fe ion (Fig. 9a). Likewise, in gp138 of bacteriophage ϕ92, the tip is stabilized by coordination of six His residues to an Fe ion (Fig. 9c) (Browning et al. 2012; Shneider et al. 2013). In gpV of bacteriophage P2 and gp45 of bacteriophage Mu, the tip domains are further stabilized by coordination to a Cl ion and a Ca ion in addition to the Fe ion (Fig. 9b, d) (Yamashita et al. 2011; Browning et al. 2012; Harada et al. 2013). The C-terminal domains of gpV and gp45 interact with the outer membrane of E. coli, indicating the importance of the tips for the initiation of cell puncture (Kageyama et al. 2009; Suzuki et al. 2010). In the β-helix domains, gp5, gpV and gp45 form a similar corkscrew structure consisting of the three intertwined monomers, whereas gp138 forms three antiparallel β-sheets (Fig. 9) (Kanamaru et al. 2002; Yamashita et al. 2011; Browning et al. 2012; Harada et al. 2013). The β-helix domains are expected to play a critical role in the cell-penetrating pathway as mentioned above.

Table 1.

Reported motifs for cell penetration

| Phage or system | Name | Oligomeric state | Proposed function | Protein data bank (PDB) ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myoviridae | |||||

| T4 | gp5 | Trimer | Needle | 1 K28 | Kanamaru et al. 2002 |

| gp5.4 | Monomer | Tip | 4KU0a | ||

| P2 | gpV | Trimer | Needle and tip | 3AQJ, 3QR7, 3QR8 | Yamashita et al. 2011; Browning et al. 2012 |

| ϕ92 | gp138 | Trimer | Needle and tip | 3PQI, 3PQH | Browning et al. 2012 |

| Mu | gp45 | Trimer | Needle and tip | 3VTO | Harada et al. 2013 |

| Podoviridae | |||||

| P22 | gp26 | Trimer | Needle | 2POH, 3C9I | Olia et al. 2007, 2009 |

| Sf6 | Trimer | Knob | 3RWN | Bhardwaj et al. 2011 | |

| ϕ29 | gp9 | Hexamer | Knob | 5FB4, 5FB5, 5FEI | Xu et al. 2016 |

| C1 | gp12 | Hexamer | Knob | 4EO2, 4EP0 | Aksyuk et al. 2012 |

| Bacterial secretion system | |||||

| T6SS | VgrG | Trimer | Needle | 4JIVb, 4JIWb | Shneider et al. 2013 |

| PAAR | Monomer | Tip | 4JIV, 4JIW | Shneider et al. 2013 | |

| VgrG from Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Trimer | Needle | 4MTKa, 4UHV | Spínola-Amilibia et al. 2016 | |

aUnpublished structure

bThe crystal structure of gp5–VgrG chimaeras

Fig. 9.

Protein needles from Myoviridae bacteriophages. a gp5 and gp5.4 from bacteriophage T4 (combined from PDB IDs: 1 K28 and 4KU0) (Kanamaru et al. 2002). b gpV from bacteriophage P2 (combined from PDB IDs: 3QR7 and 3QR8) (Browning et al. 2012). c gp138 from bacteriophage ϕ92 (PDB ID: 3PQI) (Browning et al. 2012). d gp45 from bacteriophage Mu (PDB ID: 3VTO) (Harada et al. 2013). Each color represents a different monomer. OB-fold domain Oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding domain

In contrast to the Myoviridae phages, Podoviridae phages (e.g. P22, Sf6, ϕ29, C1) have no common motifs at the end of their tail tubes. Bacteriophage P22 has a 240-Å long coiled-coil needle consisting of a trimer of gp26 as the cell-puncturing structure (Olia et al. 2007, 2009, 2011). A P22-like phage, bacteriophage Sf6, possesses a tail needle knob for contacting and penetrating the host cell surface (Bhardwaj et al. 2011). Bacteriophage ϕ29 has a tail knob formed of a cylinder of tubes consisting of gp9 and gp13 at the tip of the tail (Xu et al. 2016). The hexametric gp9 assembly is a 125-Å-long cylindrical tube-like structure that is associated with membrane penetration. A similar knob structure was observed in bacteriophage C1 (Aksyuk et al. 2012). Among the Siphoviridae phages (e.g. p2, TP901–1, SPP1, λ), bacteriophage p2 has a baseplate but no central needle (Sciara et al. 2010). The electron microscopy images of bacteriophage TP901–1 and SPP1 indicate the existence of tail tips (Plisson et al. 2007; Bebeacua et al. 2010). These structural analyses show that the needle-tip complexes are essential for cell puncture in bacteriophages but that the structures vary in size and complexity, depending on the specificity of interactions between the phages and the host.

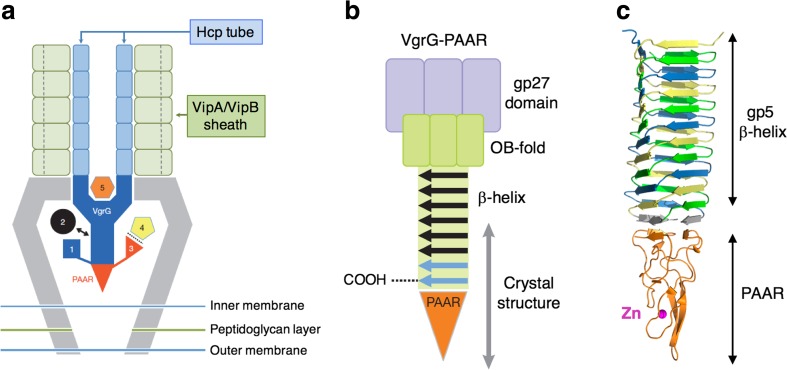

Arrangements of cell-puncturing needles are also employed in systems other than bacteriophages (Bönemann et al. 2010; Veesler and Cambillau 2011; Sarris et al. 2014; Zoued et al. 2014; Kube and Wendler 2015; Costa et al. 2015). The bacterial type VI secretion system (T6SS) is a nanomachine which is responsible for the translocation of toxic effector molecules or ions across lipid membranes, allowing predatory bacteria to kill prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (Fig. 10a) (Pukatzki et al. 2007; Kanamaru 2009; Leiman et al. 2009; Shneider et al. 2013; Ho et al. 2014). T6SS is functionally analogous to the contractile tails of bacteriophage T4. A trimeric β-helical protein needle known as the VgrG spike is a structural homolog of gp27–gp5 of bacteriophage T4, although VgrG does not include a lysozyme domain (Fig. 10b). Analysis of the crystal structure of full-length VgrG from Pseudomonas aeruginosa showed that VgrG has a shorter needle structure than gp27–gp5 with the existence of a small C-terminal extension that folds along the VgrG β-helix (Spínola-Amilibia et al. 2016). The tip of the VgrG β-helix is capped by a spike-sharpening protein known as the PAAR repeat protein. The PAAR motif, which is homologs to gp5.4 of bacteriophage T4, is stabilized by coordination of a Zn ion to three His residues and one Cys residue (Fig. 10c) (Shneider et al. 2013). In T6SS, the VgrG–PAAR complex is believed to penetrate target cells to deliver decorated effectors in a contraction-driven translocation event (Fig. 10a). Similar cell-puncturing nanomachines are found in other systems. R-type pyocins are rod-like bacteriocins related to bacteriophage P2 and T6SS and produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains to puncture and kill target cells (Nakayama et al. 2000; Ge et al. 2015). Delivery of proteins into eukaryotic cells is achieved using structurally related cell-puncturing devices such as the Photorhabdus virulence cassette (PVC) structures produced by Serratia entomophila and Photorhabdus sp. (Yang et al. 2006; Hurst et al. 2007), the anti-feeding prophage (Afp) in Serratia entomophila (Heymann et al. 2013; Hurst et al. 2004) and the metamorphosis-associated contractile structure of Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (Shikuma et al. 2014). These findings strongly suggest that the structurally conserved needle motifs found in bacteriophages, bacterial secretion systems, bacteriocins and other protein injection systems are optimized for efficient cell penetration.

Fig. 10.

T6SS, the bacterial type VI secretion system, as a nanomachine for molecular injection (adapted from Shneider et al. 2013). a Model organization of the T6SS baseplate. Molecules 1–5 indicate the predicted effector molecules. b The conserved domains consisting of the VgrG–PAAR complex in T6SS. c Crystal structure of a chimeric protein including gp5-VgrG and the PAAR complex (PDB ID: 4JIV)

Engineering of gp5

An artificial protein needle based on the β-helix domain of gp5

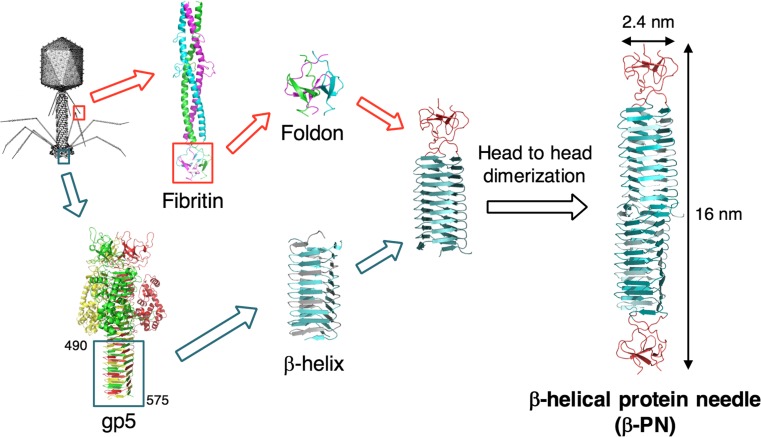

We have constructed a robust β-helical protein needle (β-PN) by integrating the β-helix domain of gp5 and foldon (the stabilization motif of fibritin) of bacteriophage T4 (Yokoi et al. 2010). The most stable region of the β-helix at the C-terminal end of gp5 (residues 490–575) was genetically fused with foldon to inhibit random aggregation of the β-helix. The chimeric protein self-assembles to form a trimer–dimer β-PN via head-to-head dimerization (Fig. 11). β-PN has high stability under high temperatures (< 100 °C), at pH 2–10 and in the presence of organic solvents (50–70%). Buth et al. (2015) reported similar trimer–dimer needle structures from the C-terminal β-helix domain of gp5. These results indicate that the β-helix is a useful self-assembly unit to form the extended needle structure.

Fig. 11.

Construction of the β-helical protein needle (β-PN) by genetic fusion of the β-helix of gp5 and foldon of fibritin from bacteriophage T4 (Yokoi et al. 2010)

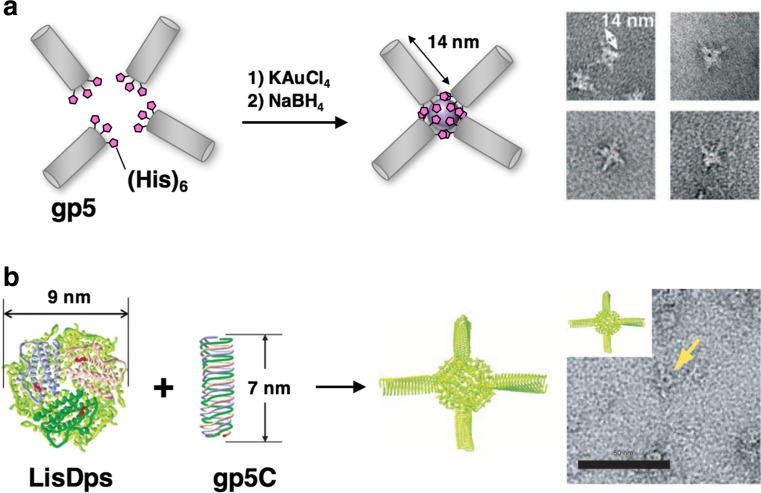

Nanomaterials based on gp5

The needle structure of gp5 has been utilized as a component in the construction of a supramolecular assembly by two different approaches (Sugimoto et al. 2006; Ueno et al. 2006). In our strategy, a triad of (His)6 fragments is introduced at the C-termini of gp5 for coordination to gold ions (Ueno et al. 2006). Upon coordination of the triad of (His)6 of gp5 to gold ions and subsequent reduction by NaBH4, a tetrapod assembly of gp5 with gold nanoclusters is constructed (Fig. 12a). The tetrapod structure is selectively constructed based on the electrostatic repulsion of the negatively charged surface of the C-termini of gp5. Yamashita et al. reported construction of a ball-and-spike protein architecture consisting of the C-terminal domain of gp5 (gp5C) and a spherical cage protein known as Dps from the bacterium Listeria innocua (LisDps) (Sugimoto et al. 2006). By fusing the C-terminus of gp5C to the N terminus of LisDps through a flexible linker, the fusion protein is induced to self-assemble to form a ball-and-spike protein supramolecule (Fig. 12b). These results indicate that the stable needle structure of gp5 is a useful scaffold for the construction of various three-dimensional nano-architectures.

Fig. 12.

a Schematic image and TEM images of a tetrapod assembly of gp5 via formation of an Au nanocluster (adapted from Ueno et al. 2006). b Schematic image and TEM image of the supramolecular assembly consisting of LisDps, a spherical cage protein, and gp5C, the C-terminal domain of gp5 (adapted from Sugimoto et al. 2006)

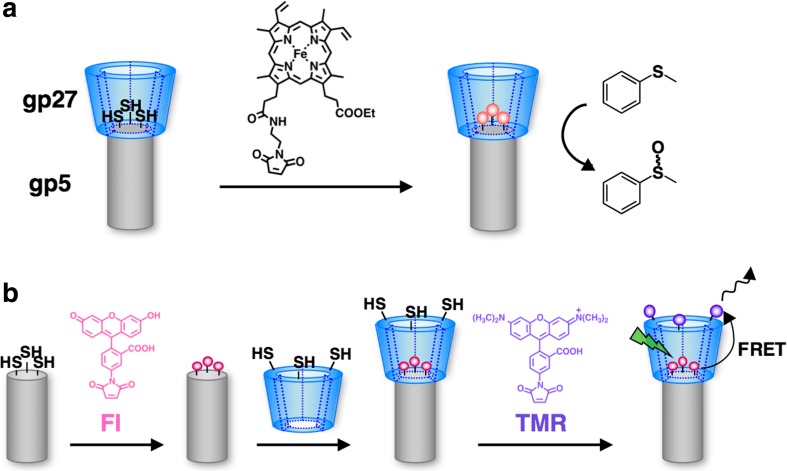

The cup-shaped structure of gp27–gp5 has been utilized as a nano-environment for catalytic reactions (Fig. 13) (Koshiyama et al. 2008, 2009). Fe(III) protoporphyrin units were linked to Cys residues introduced on the inside of the cup of gp27–gp5 (Fig. 13a) (Koshiyama et al. 2008). Crystal structure analysis and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry confirmed complete modification of the Fe(III) protoporphyrin units. The composite has high catalytic activity for H2O2-dependent sulfoxidation of thioanisole, which is six- to tenfold greater than that of the Fe(III) protoporphyrin complex. The acceleration of the catalytic reactions is expected to be due to the hydrophobic environment formed by the attachment of the gp27 cup structure to the top of gp5 needle.

Fig. 13.

a Schematic drawing of construction of an Fe(III) protoporphyrin and gp27–gp5 composite to promote a catalytic sulfoxidation reaction (Koshiyama et al. 2008). b Schematic representation of hetero-modification of fluorescein (Fl, donor) and tetramethylrhodamine (TMR, acceptor) on gp27–gp5 to induce fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (Koshiyama et al. 2009)

The cup structure of gp27–gp5 was utilized to construct an energy transfer system (Fig. 13b) (Koshiyama et al. 2009). Highly efficient fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) was observed after dual-modification of a donor fluorescein (Fl) molecule and an acceptor tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) molecule to the introduced cysteine residues of gp5 and gp27, respectively. In contrast, altering the conjugation sites for TMR and Fl was found to induce significant fluorescence self-quenching of TMR. These results suggest that the cup and needle structures of gp27–gp5 provide useful templates for precise placement of the functional molecules on their surfaces.

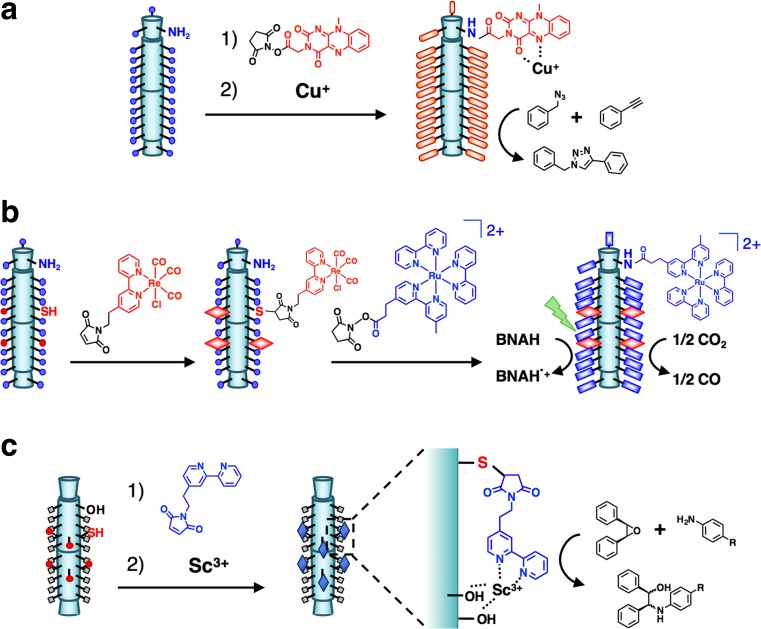

β-PN-based biocatalysts

Since β-PN is a regular triangular prismatic structure with high stability, it is an ideal template to use in the construction of biocatalysts by alignment of metal complexes on the surface (Inaba et al. 2014a). Yokoi et al. (2010) chemically conjugated flavin molecules to Lys residues aligned on the plane of β-PN at intervals of 10–15 Å (Fig. 14a). The structural integrity of β-PN was retained even after modification of the flavins. The flavin–needle composite accelerates the rate of an azide–alkyne [3 + 2] cycloaddition in the presence of a Cu(I) ion, with 33-fold higher efficiency than that of a polyLys-flavin composite due to the structural restriction which maintains the mono-coordination geometry on the surface.

Fig. 14.

Construction of biocatalysts based on β-PN. a Modification of flavins and subsequent Cu(I) coordination on β-PN for catalytic enhancement of an azide–alkyne [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction (Yokoi et al. 2010). b Sequential modification of Re and Ru complexes on β-PN for photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO by electron transfer from the Ru to Re complex in the presence of BNAH (1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide) under irradiation with visible light (Yokoi et al. 2011). c Semi-synthesis of a catalytic Sc(III) complex by coordination of the bpy (2,2′-bipyridyl) and the two –ROH groups of β-PN for epoxide ring-opening reactions (Inaba et al. 2012)

Alignment of two types of metal complexes, Ru(bpy)3 (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridyl) and Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl, on the surface of β-PN improves the photocatalytic system by enhancing the rate of electron transfer between the metal complexes (Fig. 14b) (Yokoi et al. 2011). Stepwise chemical modifications of Cys and Lys of β-PN were carried out with Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl and Ru(bpy)3, respectively. Under irradiation of the dual-modified complex with visible light (500 nm), the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO accelerates in the presence of 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide (BNAH). The turnover frequency for CO production per Re ion of the dual-modified complex was found to be 3.3-fold higher than that of a mixture of Ru(bpy)2-[4-(2-carboxylethyl)-4-methyl-2,2-bipyridyl]-(PF6)2 (Ru-COOH) and β-PN modified with the Re complex. The improvement of the reactivity was found to be due to the proximity effect of the Ru and Re moieties on β-PN. The results indicate that the positions of the different types of metal complexes can be arranged and optimized on β-PN to accelerate catalytic reactions.

An artificial Sc(III) enzyme was constructed by combining a conjugated bpy ligand and –ROH groups of Thr and Ser on the surface of β-PN (Fig. 14c) (Inaba et al. 2012). The bpy group was conjugated to Cys residues that were introduced at positions adjacent to the Thr and Ser of β-PN. The Sc(III) complex formed by tetradentate coordination of the bpy and the two –ROH groups to a Sc(III) ion was found to be capable of catalyzing various epoxide ring-opening reactions. The conversion of the complex was found to be more than 20-fold greater than that produced by mixtures of β-PN/bpy and L-threonine/bpy. The catalytically active Sc(III) complex is obtained only when bpy is located adjacent to the two –ROH groups of Thr aligned on the surface of β-PN. This work shows that the semi-synthetic approach is useful for the construction of artificial metalloenzymes in situ, by combining a simple synthetic ligand and natural coordinating amino acids on the host proteins. These results demonstrate that β-PN is a useful platform for the construction of artificial metalloenzymes via modifications of the metal complexes at selected positions on the surface.

Protein needle as a cell-penetrating nanomachine

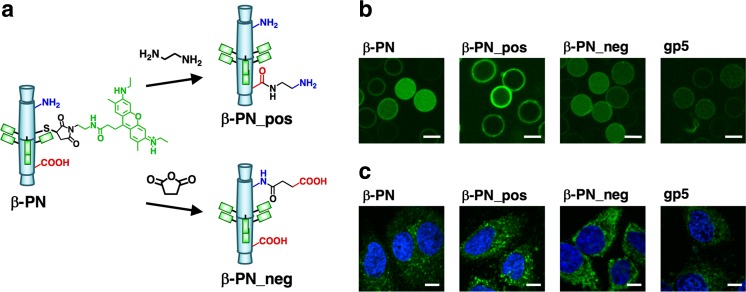

Cell penetration

Since bacteriophage T4 and other systems use protein needles consisting of β-helix domains to puncture the cell membranes as mentioned above, it is expected that β-PN reconstructed from the β-helix of gp5 is capable of cell penetration. We evaluated the penetration of fluorescent-labeled β-PN into living cells to investigate this hypothesis (Sanghamitra et al. 2014). Since the mechanisms of cellular uptake are influenced by the surface charge, we prepared positively and negatively charged β-PN by modifying the carboxylic acids and amines on the surface, respectively (β-PN_pos and β-PN_neg, Fig. 15a). β-PN was homogeneously internalized into human red blood cells, which lack endogenous endocytic machinery (Fig. 15b). This observation suggests that β-PN enables non-endocytic cell penetration. The uptake efficiency of β-PN into hRBCs was found to be higher than that of β-PN_pos and β-PN_neg, indicating that the surface charge of β-PN was enhanced for the non-endocytic penetration. The cellular uptake efficiency of β-PN into HeLa cells was found to be lower than that of β-PN_pos and β-PN_neg (Fig. 15c). It was shown that the uptake of β-PN into HeLa cells incorporates endocytosis-independent mechanisms with partial macropinocytosis dependence. β-PN_pos and β-PN_neg have higher endocytosis dependence compared to β-PN. Gp5 has lower uptake efficiency than β-PN in hRBCs and HeLa cells. These results indicate that the β-helical structure and the surface charge of β-PN are optimized for non-endocytic penetration. This study demonstrates that the needle motif of bacteriophage T4 has penetration functionality not only when it is embedded in the phage but also even after isolation from the phage. Thus, the natural bio-nanomachine of bacteriophage T4 serves as a source of inspiration for designing new cell-penetrating materials.

Fig. 15.

Cell penetration of β-PN (adapted from Sanghamitra et al. 2014). a Modifications of charged residues of ATTO520-labeled β-PN. b, c Confocal fluorescence images of uptake into human red blood cells (b) (scale bars 5 μm) and HeLa cells (c) (scale bars 10 μm). β-PN_pos, β-PN_neg Positively and negatively charged β-PN, respectively

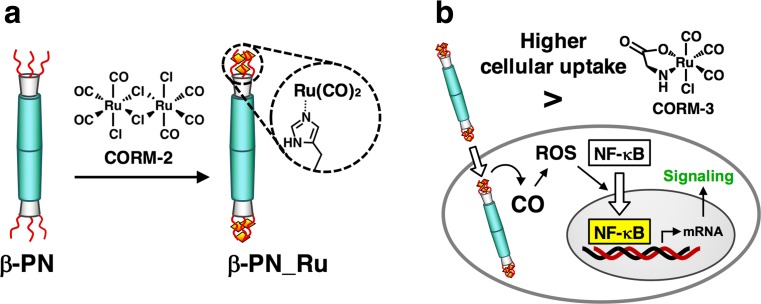

CO delivery

β-PN has been used as a carrier for intracellular delivery of carbon monoxide (CO) (Inaba et al. 2015a). CO functions as a gas signaling molecule that mediates anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects (Motterlini and Otterbein 2010). CO-releasing molecules (CORMs) have been incorporated into macromolecular carriers as systems for efficient intracellular CO delivery (García-Gallego and Bernardes 2014; Heinemann et al. 2014; Inaba et al. 2015b). Most CORMs are composed of transition metal carbonyl complexes. In our CO delivery strategy, Ru(CO)2 moieties were introduced at both of the tips of β-PN by reacting triads of (His)6 at the C-termini with [Ru(CO)3Cl2]2 (CORM-2) (Fig. 16a) (Inaba et al. 2015a). The resulting composite (β-PN_Ru) exhibits a 12-fold prolonged CO release rate relative to a representative CORM, Ru(CO)3Cl(glycinate), which is known as CORM-3. The cellular uptake efficiency of β-PN_Ru was found to be more than 20-fold higher than that of CORM-3 and of the protein cage ferritin–Ru(CO)2 composite (Fujita et al. 2014). Thus, β-PN_Ru can deliver Ru carbonyl with significantly high uptake efficiency. CO delivered by β-PN_Ru induces the generation of reactive oxygen species that activate transcriptional factor nuclear factor-kappaB, subsequently leading to significant induction of the expression of its target genes, HO1, NQO1 and IL6 (Fig. 16b). Thus, β-PN can be engineered for the fabrication of effective organometallic tools to modulate cellular signaling pathways.

Fig. 16.

β-PN as a carrier of carbon monoxide (CO) (adapted from Inaba et al. 2015a). a Construction of an Ru carbonyl–protein needle construct (β-PN_Ru). b Intracellular CO delivery by β-PN_Ru and the subsequent signaling pathway. CORM CO-releasing molecule, ROS reactive oxygen species, NF-κB nuclear factor-kappaB

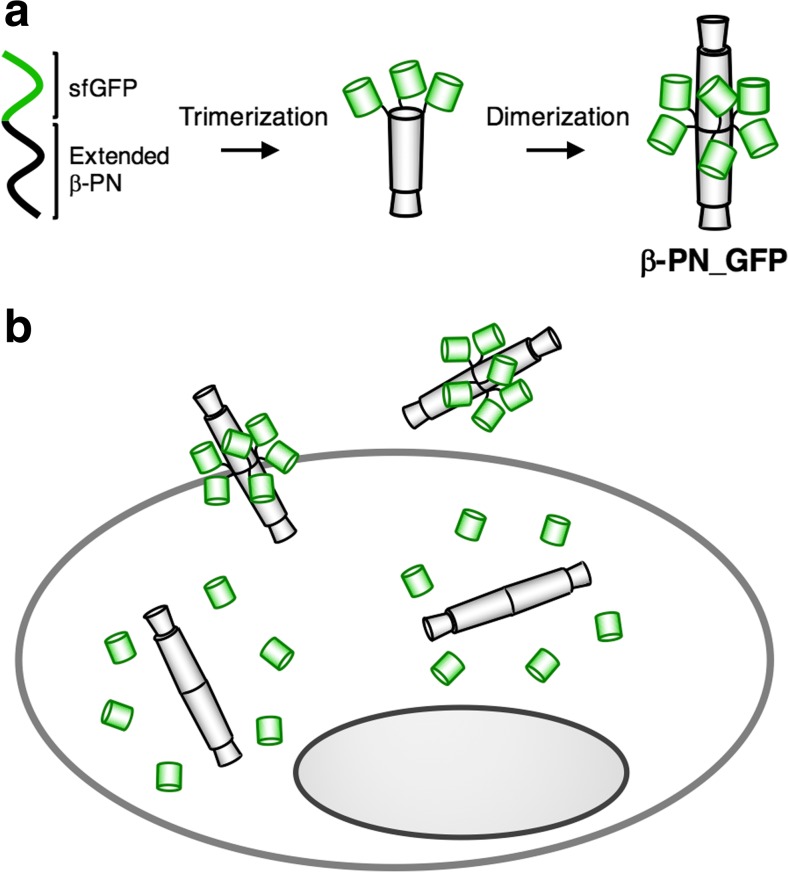

Protein delivery

Gp5 is a natural carrier for protein delivery since three lysozyme domains of gp5 are cleaved and released in the periplasm after penetration to lyse the inner membrane of E. coli (Kanamaru et al. 2002, 2005). Thus, we expected that β-PN could be used as a carrier for the intracellular delivery of exogenous proteins. Superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) was delivered by genetic fusion with β-PN (Fig. 17) (Inaba et al. 2014b). By fusing the C-terminus of sfGFP with the N-terminus of β-PN monomer, six molecules of sfGFP were introduced into one molecule of β-PN as a result of the dimerization of two trimers (β-PN_GFP, Fig. 17a). The needle structure of β-PN was found to be retained in the buffer and cell culture medium even after fusion of six molecules of sfGFP. The sfGFP molecules and β-PN could be cleaved inside cells because C-terminal peptides of sfGFP are susceptible to proteolysis. After incubation of β-PN_GFP with HeLa cells, the cell lysate and the supernatant of cell medium were analyzed by gel permeation chromatography. The structure of β-PN_GFP was found to be retained in the supernatant, whereas the cleaved sfGFP from β-PN_GFP was observed in the cell lysate. These results indicate that the sfGFP moiety of β-PN_GFP is cleaved after cell penetration via an auto-cleavage reaction (Fig. 17b). The protein delivery system based on β-PN will be applicable to in vitro and in vivo protein delivery.

Fig. 17.

β-PN as a carrier of proteins (adapted from Inaba et al. 2014b). a Synthesis of the superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP)–protein needle construct β-PN_GFP. b Intracellular delivery of sfGFP by β-PN_GFP

Conclusion and perspectives

In this review we have summarized the recent design and development of nanomaterials using components of bacteriophage T4 as molecular templates and scaffolds. The unique structures of the components of bacteriophage T4 enable fabrication of various nanomaterials, such as molecular transporters, three-dimensional architectures, biocatalysts and cell-penetrating materials. In particular, we demonstrated cell penetration of a β-helical protein needle (β-PN) consisting of the β-helix domain of gp5 in bacteriophage T4. β-PN delivers molecular cargos to living cells in a manner similar to the delivery of lysozyme into host cells by gp5 embedded in bacteriophage T4. These studies indicate that the component proteins can be extracted from the natural bio-nanomachines while preserving their original functions. Investigations of cell-puncturing needles in bacteriophages, bacterial secretion systems, bacteriocins and other protein injection systems strongly indicate that these protein needles are optimized for cell penetration and can be used as cell-penetrating materials. Other component structures of bacteriophage T4, such as the head, the sheath, the tail fiber and the baseplate, are also conserved in other bacteriophages and other injection systems (Veesler and Cambillau 2011; Brackmann et al. 2017). Thus, by using these common motifs, it is expected that new nanomachines with dynamic functions, such as receptor binding, DNA transfer and structural changes, will be developed. Other tailed bacteriophages with different infection mechanisms will also provide interesting molecular scaffolds (Xu and Xiang 2017). Bioinformatics analysis is useful for predicting the function of unknown gene products. In summary, natural nanomachines such as bacteriophage T4 provide inspiration for the development of dynamic functions via extraction of various component structures and further chemical and genetic engineering. Elucidation of the dynamics of each component by biophysical approaches is an important strategy for investigating the relationships between the structures and functions of natural nanomachines in order to advance future designs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Research Fellowship for Young Scientists of JSPS for H.I. (No. 4240) and by JSPS KAKENHI grant nos. JP13F03343, JP16H04177, JP16K13095, JP23350080, and JP26102513 and from Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research for T.U.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Hiroshi Inaba declares that he has no conflict of interest. Takafumi Ueno declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘Biomolecules to Bio-nanomachines—Fumio Arisaka 70th Birthday’ edited by Damien Hall.

References

- Aksyuk AA, Leiman PG, Kurochkina LP, Shneider MM, Kostyuchenko VA, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rossmann MG. The tail sheath structure of bacteriophage T4: a molecular machine for infecting bacteria. EMBO J. 2009;28:821–829. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksyuk AA, Bowman VD, Kaufmann B, Fields C, Klose T, Holdaway HA, Fischetti VA, Rossmann MG. Structural investigations of a Podoviridae streptococcus phage C1, implications for the mechanism of viral entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14001–14006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207730109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer MJ, Liu JL. Bacteriophage T4 nanoparticles as materials in sensor applications: variables that influence their organization and assembly on surfaces. Sensors. 2009;9:6298–6311. doi: 10.3390/s90806298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arisaka F, Yap ML, Kanamaru S, Rossmann MG. Molecular assembly and structure of the bacteriophage T4 tail. Biophys Rev. 2016;8:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s12551-016-0230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartual SG, Otero JM, Garcia-Doval C, Llamas-Saiz AL, Kahn R, Fox GC, van Raaij MJ. Structure of the bacteriophage T4 long tail fiber receptor-binding tip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20287–20292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011218107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeacua C, Bron P, Lai L, Vegge CS, Brøndsted L, Spinelli S, Campanacci V, Veesler D, van Heel M, Cambillau C. Structure and molecular assignment of lactococcal phage TP901-1 baseplate. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39079–39086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj A, Molineux IJ, Casjens SR, Cingolani G. Atomic structure of bacteriophage Sf6 tail needle knob. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30867–30877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bönemann G, Pietrosiuk A, Mogk A. Tubules and donuts: a type VI secretion story. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:815–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackmann M, Nazarov S, Wang J, Basler M. Using force to punch holes: mechanics of contractile nanomachines. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning C, Shneider MM, Bowman VD, Schwarzer D, Leiman PG. Phage pierces the host cell membrane with the iron-loaded spike. Structure. 2012;20:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buth SA, Menin L, Shneider MM, Engel J, Boudko SP, Leiman PG. Structure and biophysical properties of a triple-stranded beta-helix comprising the central spike of bacteriophage T4. Viruses. 2015;7:4676–4706. doi: 10.3390/v7082839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa TRD, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Meir A, Prevost MS, Redzej A, Trokter M, Waksman G. Secretion systems in gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:343–359. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daube SS, Arad T, Bar-Ziv R. Cell-free co-synthesis of protein nanoassemblies: tubes, rings, and doughnuts. Nano Lett. 2007;7:638–641. doi: 10.1021/nl062560n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov AV, Kurochkina LP, Mesyanzhinov VV. Engineering of bacteriophage T4 tail sheath protein. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;67:1366–1370. doi: 10.1023/A:1021857926152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Rossmann MG. Molecular architecture of tailed double-stranded DNA phages. Bacteriophage. 2014;4:e28281. doi: 10.4161/bact.28281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Chipman PR, Leiman PG, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rao VB, Rossmann MG. Molecular architecture of the prolate head of bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6003–6008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400444101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Tanaka Y, Sho T, Ozeki S, Abe S, Hikage T, Kuchimaru T, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Ueno T. Intracellular CO release from composite of ferritin and ruthenium carbonyl complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16902–16908. doi: 10.1021/ja508938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Kottadiel VI, Rao VB, Smith DE. Single phage T4 DNA packaging motors exhibit large force generation, high velocity, and dynamic variability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16868–16873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704008104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gallego S, Bernardes GJL. Carbon-monoxide-releasing molecules for the delivery of therapeutic CO in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9712–9721. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge P, Scholl D, Leiman PG, Yu X, Miller JF, Zhou ZH. Atomic structures of a bactericidal contractile nanotube in its pre- and postcontraction states. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granell M, Namura M, Alvira S, Kanamaru S, van Raaij MJ (2017) Crystal structure of the carboxy-terminal region of the bacteriophage T4 proximal long tail fiber protein gp34. Viruses. 10.3390/v9070168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harada K, Yamashita E, Nakagawa A, Miyafusa T, Tsumoto K, Ueno T, Toyama Y, Takeda S. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of mu phage central spike and functions of bound calcium ion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann SH, Hoshi T, Westerhausen M, Schiller A. Carbon monoxide—physiology, detection and controlled release. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3644–3617. doi: 10.1039/C3CC49196J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann JB, Bartho JD, Rybakova D, Venugopal HP, Winkler DC, Sen A, Hurst MR, Mitra AK. Three-dimensional structure of the toxin-delivery particle antifeeding prophage of Serratia entomophila. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:25276–25284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.456145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho BT, Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Gao F, Li N. T4 virus-based toolkit for the direct synthesis and 3D organization of metal quantum particles. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:14397–14403. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Margolin W, Molineux IJ, Liu J. Structural remodeling of bacteriophage T4 and host membranes during infection initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E4919–E4928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501064112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst MRH, Glare TR, Jackson TA. Cloning Serratia entomophila antifeeding genes–a putative defective prophage active against the grass grub Costelytra zealandica. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5116–5128. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.5116-5128.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst MRH, Beard SS, Jackson TA, Jones SM. Isolation and characterization of the Serratia entomophila antifeeding prophage. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;270:42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman P, Valluzzi R, Goldberg E. Design of protein struts for self-assembling nanoconstructs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8488–8493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132544299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Semi-synthesis of an artificial scandium(III) enzyme with a b-helical bio-nanotube. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:11424–11427. doi: 10.1039/c2dt31030a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Protein needles as molecular templates for artificial metalloenzymes. Isr J Chem. 2014;55:40–50. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201400097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Sanghamitra NJM, Fukai T, Matsumoto T, Nishijo K, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Intracellular protein delivery system with protein needle–GFP construct. Chem Lett. 2014;43:1505–1507. doi: 10.1246/cl.140481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Sanghamitra NJM, Fujita K, Sho T, Kuchimaru T, Kitagawa S, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Ueno T. A metal carbonyl-protein needle composite designed for intracellular CO delivery to modulate NF-kB activity. Mol BioSyst. 2015;11:3111–3118. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00327J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Fujita K, Ueno T. Design of biomaterials for intracellular delivery of carbon monoxide. Biomater Sci. 2015;3:1423–1438. doi: 10.1039/C5BM00210A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama Y, Murayama M, Onodera T, Yamada S, Fukada H, Kudou M, Tsumoto K, Toyama Y, Kado S, Kubota K, Takeda S. Observation of the membrane binding activity and domain structure of gpV, which comprises the tail spike of bacteriophage P2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10129–10135. doi: 10.1021/bi900928n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru S. Structural similarity of tailed phages and pathogenic bacterial secretion systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4067–4068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901205106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru S, Leiman PG, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Rossmann MG. Structure of the cell-puncturing device of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 2002;415:553–557. doi: 10.1038/415553a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru S, Ishiwata Y, Suzuki T, Rossmann MG, Arisaka F. Control of bacteriophage T4 tail lysozyme activity during the infection process. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam JD, Drake JW, Kreuzer KN, Mosig G, Hall DH, Eiserling FA, Black LW, Spicer EK, Kutter E, Carlson K, Miller ES, editors. Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. Washington D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Mirshekari H, Basri SMM, Bahrami S, Moghoofei M, Hamblin MR. Bacteriophages and phage-inspired nanocarriers for targeted delivery of therapeutic cargos. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;106:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keten S, Alvarado JFR, Müftü S, Buehler MJ. Nanomechanical characterization of the triple b-helix domain in the cell puncture needle of bacteriophage T4 virus. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2009;2:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0047-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keten S, Xu Z, Buehler MJ. Triangular core as a universal strategy for stiff nanostructures in biology and biologically inspired materials. Mater Sci Eng C. 2011;31:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2011.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondabagil K, Dai L, Vafabakhsh R, Ha T, Draper B, Rao VB. Designing a nine cysteine-less DNA packaging motor from bacteriophage T4 reveals new insights into ATPase structure and function. Virology. 2014;468:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiyama T, Yokoi N, Ueno T, Kanamaru S, Nagano S, Shiro Y, Arisaka F, Watanabe Y. Molecular design of heteroprotein assemblies providing a bionanocup as a chemical reactor. Small. 2008;4:50–54. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiyama T, Ueno T, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Watanabe Y. Construction of an energy transfer system in the bio-nanocup space by heteromeric assembly of gp27 and gp5 proteins isolated from bacteriophage T4. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:2649–2654. doi: 10.1039/b904297k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuchenko VA, Leiman PG, Chipman PR, Kanamaru S, van Raaij MJ, Arisaka F, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rossmann MG. Three-dimensional structure of bacteriophage T4 baseplate. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:688–693. doi: 10.1038/nsb970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottadiel VI, Rao VB, Chemla YR. The dynamic pause-unpackaging state, an off-translocation recovery state of a DNA packaging motor from bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:20000–20005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209214109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudelka KJ, Manchester M. Chemically modified viruses: principles and applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kube S, Wendler P. Structural comparison of contractile nanomachines. AIMS Biophys. 2015;2:88–115. doi: 10.3934/biophy.2015.2.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiman PG, Kanamaru S, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Rossmann MG. Structure and morphogenesis of bacteriophage T4. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2356–2370. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiman PG, Basler M, Ramagopal UA, Bonanno JB, Sauder JM, Pukatzki S, Burley SK, Almo SC, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4154–4159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiman PG, Arisaka F, van Raaij MJ, Kostyuchenko VA, Aksyuk AA, Kanamaru S, Rossmann MG. Morphogenesis of the T4 tail and tail fibers. Virol J. 2010;7:355. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang Q. Fabrication of nanoarchitectures templated by virus-based nanoparticles: strategies and applications. Small. 2014;10:230–245. doi: 10.1002/smll.201301393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Qiao J, Niu Z, Wang Q. Natural supramolecular building blocks: from virus coat proteins to viral nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:6178–6194. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35108k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JL, Dixit AB, Robertson KL, Qiao E, Black LW. Viral nanoparticle-encapsidated enzyme and restructured DNA for cell delivery and gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13319–13324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321940111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Nolte RJM, Cornelissen JJLM. Virus-based nanocarriers for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:811–825. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliori AD, Keller N, Alam TI, Mahalingam M, Rao VB, Arya G, Smith DE. Evidence for an electrostatic mechanism of force generation by the bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging motor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4173. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody MF. Structure of the sheath of bacteriophage T4: I. Structure of the contracted sheath and polysheath. J Mol Biol. 1967;25:167–200. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motterlini R, Otterbein LE. The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:728–743. doi: 10.1038/nrd3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Takashima K, Ishihara H, Shinomiya T, Kageyama M, Kanaya S, Ohnishi M, Murata T, Mori H, Hayashi T. The R-type pyocin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is related to P2 phage, and the F-type is related to lambda phage. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:213–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishima W, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Kitao A. Screw motion regulates multiple functions of T4 phage protein gene product 5 during cell puncturing. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13571–13576. doi: 10.1021/ja204451g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olia AS, Casjens S, Cingolani G. Structure of phage P22 cell envelope–penetrating needle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1221–1226. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olia AS, Casjens S, Cingolani G. Structural plasticity of the phage P22 tail needle gp26 probed with xenon gas. Protein Sci. 2009;18:537–548. doi: 10.1002/pro.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olia AS, Prevelige PE, Jr, Johnson JE, Cingolani G. Three-dimensional structure of a viral genome-delivery portal vertex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plisson C, White HE, Auzat I, Zafarani A, São-José C, Lhuillier S, Tavares P, Orlova EV. Structure of bacteriophage SPP1 tail reveals trigger for DNA ejection. EMBO J. 2007;26:3720–3728. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VB, Black LW. Cloning, overexpression and purification of the terminase proteins gp16 and gp17 of bacteriophage T4: Construction of a defined in-vitro DNA packaging system using purified terminase proteins. J Mol Biol. 1988;200:475–488. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VB, Black LW. Structure and assembly of bacteriophage T4 head. Virol J. 2010;7:356. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KL, Soto CM, Archer MJ, Odoemene O, Liu JL. Engineered T4 viral nanoparticles for cellular imaging and flow cytometry. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:595–604. doi: 10.1021/bc100365j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann MG, Rao VB, editors. Viral molecular machines. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann MG, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Leiman PG. The bacteriophage T4 DNA injection machine. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghamitra NJM, Inaba H, Arisaka F, Wang DO, Kanamaru S, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Plasma membrane translocation of a protein needle based on a triple-stranded b-helix motif. Mol BioSyst. 2014;10:2677–2683. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00293H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris PF, Ladoukakis ED, Panopoulos NJ, Scoulica EV. A phage tail-derived element with wide distribution among both prokaryotic domains: a comparative genomic and phylogenetic study. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:1739–1747. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciara G, Bebeacua C, Bron P, Tremblay D, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Lichière J, van Heel M, Campanacci V, Moineau S, Cambillau C. Structure of lactococcal phage p2 baseplate and its mechanism of activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6852–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000232107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikuma NJ, Pilhofer M, Weiss GL, Hadfield MG, Jensen GJ, Newman DK. Marine tubeworm metamorphosis induced by arrays of bacterial phage tail-like structures. Science. 2014;343:529–533. doi: 10.1126/science.1246794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneider MM, Buth SA, Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ, Leiman PG. PAAR-repeat proteins sharpen and diversify the type VI secretion system spike. Nature. 2013;500:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nature12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spínola-Amilibia M, Davó-Siguero I, Ruiz FM, Santillana E, Medrano FJ, Romero A. The structure of VgrG1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the needle tip of the bacterial type VI secretion system. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2016;72:22–33. doi: 10.1107/S2059798315021142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Kanamaru S, Iwasaki K, Arisaka F, Yamashita I. Construction of a ball-and-spike protein supramolecule. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2725–2728. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Kondabagil K, Gentz PM, Rossmann MG, Rao VB. The structure of the ATPase that powers DNA packaging into bacteriophage T4 procapsids. Mol Cell. 2007;25:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Kondabagil K, Draper B, Alam TI, Bowman VD, Zhang Z, Hegde S, Fokine A, Rossmann MG, Rao VB. The structure of the phage T4 DNA packaging motor suggests a mechanism dependent on electrostatic forces. Cell. 2008;135:1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhang X, Gao S, Rao PA, Padilla-Sanchez V, Chen Z, Sun S, Xiang Y, Subramaniam S, Rao VB, Rossmann MG. Cryo-EM structure of the bacteriophage T4 portal protein assembly at near-atomic resolution. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7548. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Yamada S, Toyama Y, Takeda S. The C-terminal domain is sufficient for host-binding activity of the mu phage tail-spike protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1738–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Arisaka F, Ishii S, Kyogoku Y. Structural studies of the contractile tail sheath protein of bacteriophage T4. 1. Conformational change of the tail sheath upon contraction as probed by differential chemical modification. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5050–5056. doi: 10.1021/bi00473a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao P, Mahalingam M, Marasa BS, Zhang Z, Chopra AK, Rao VB. In vitro and in vivo delivery of genes and proteins using the bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging machine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5846–5851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300867110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NMI, Prokhorov NS, Guerrero-Ferreira RC, Shneider MM, Browning C, Goldie KN, Stahlberg H, Leiman PG. Structure of the T4 baseplate and its function in triggering sheath contraction. Nature. 2016;533:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature17971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T. Functionalization of viral protein assemblies by self-assembly reactions. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:3741–3745. doi: 10.1039/b806296j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T, Koshiyama T, Tsuruga T, Goto T, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Watanabe Y. Bionanotube tetrapod assembly by in situ synthesis of a gold nanocluster with (gp5–His6)3 from bacteriophage T4. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4508–4512. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafabakhsh R, Kondabagil K, Earnest T, Lee KS, Zhang Z, Dai L, Dahmen KA, Rao VB, Ha T. Single-molecule packaging initiation in real time by a viral DNA packaging machine from bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:15096–15101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407235111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veesler D, Cambillau C. A common evolutionary origin for tailed-bacteriophage functional modules and bacterial machineries. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:423–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen AM, Steinmetz NF. Design of virus-based nanomaterials for medicine, biotechnology, and energy. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:4074–4126. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00287G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendell D, Jing P, Geng J, Subramaniam V, Lee TJ, Montemagno C, Guo P. Translocation of double-stranded DNA through membrane-adapted phi29 motor protein nanopores. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:765–772. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Xiang Y (2017) Membrane penetration by bacterial viruses. J Virol 91:e00162–17. 10.1128/JVI.00162-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu J, Gui M, Wang D, Xiang Y. The bacteriophage f29 tail possesses a pore-forming loop for cell membrane penetration. Nature. 2016;534:544–547. doi: 10.1038/nature18017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita E, Nakagawa A, Takahashi J, Tsunoda K, Yamada S, Takeda S. The host-binding domain of the P2 phage tail spike reveals a trimeric iron-binding structure. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011;67:837–841. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Dowling AJ, Gerike U, ffrench-Constant RH, Waterfield NR. Photorhabdus virulence cassettes confer injectable insecticidal activity against the wax moth. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2254–2261. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2254-2261.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap ML, Klose T, Arisaka F, Speir JA, Veesler D, Fokine A, Rossmann MG. Role of bacteriophage T4 baseplate in regulating assembly and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:2654–2659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601654113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi N, Inaba H, Terauchi M, Stieg AZ, Sanghamitra NJM, Koshiyama T, Yutani K, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Hikage T, Suzuki A, Yamane T, Gimzewski JK, Watanabe Y, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Construction of robust bio-nanotubes using the controlled self-assembly of component proteins of bacteriophage T4. Small. 2010;6:1873–1879. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi N, Miura Y, Huang C-Y, Takatani N, Inaba H, Koshiyama T, Kanamaru S, Arisaka F, Watanabe Y, Kitagawa S, Ueno T. Dual modification of a triple-stranded b-helix nanotube with Ru and re metal complexes to promote photocatalytic reduction of CO2. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2074–2076. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03015e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoued A, Brunet YR, Durand E, Aschtgen M-S, Logger L, Douzi B, Journet L, Cambillau C, Cascales E. Architecture and assembly of the type VI secretion system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:1664–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]