Abstract

Designing novel protein–protein interactions (PPIs) with high affinity is a challenging task. Directed evolution, a combination of randomization of the gene for the protein of interest and selection using a display technique, is one of the most powerful tools for producing a protein binder. However, the selected proteins often bind to the target protein at an undesired surface. More problematically, some selected proteins bind to their targets even though they are unfolded. Current state-of-the-art computational design methods have successfully created novel protein binders. These computational methods have optimized the non-covalent interactions at interfaces and thus produced artificial protein complexes. However, to date there are only a limited number of successful examples of computationally designed de novo PPIs. De novo design of coiled-coil proteins has been extensively performed and, therefore, a large amount of knowledge of the sequence–structure relationship of coiled-coil proteins has been accumulated. Taking advantage of this knowledge, de novo design of inter-helical interactions has been used to produce artificial PPIs. Here, we review recent progress in the in silico design and rational design of de novo PPIs and the use of α-helices as interfaces.

Keywords: Protein–protein interactions, Computational design, Novel protein binding, De novo interactions, Interface

Introduction

Creation of an artificial protein–protein interface (PPI) is one of the critical steps in developing an artificial protein complex. The formation of PPIs generally induces an unfavorable entropy change (McManus et al. 2016). However, enthalpy change, which relies on the network of non-covalent bonds, such as hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and van der Waals forces, compensates for the entropy cost, thus generating a thermodynamically stable complex (McManus et al. 2016). To satisfy the energetic requirements of the bound state, the interfaces of two proteins should have shape and chemical complementarity. Directed evolution is a powerful tool for creating novel protein binding to a target protein because the method can produce a de novo PPI without having to take into consideration the shape and chemical complementarity between the interfaces of the two protein molecules (Jäckel et al. 2008). However, the artificially evolved proteins often bind to the target in an undesired binding mode (Chin and Schepartz 2001; Gemperli et al. 2005; Karanicolas et al. 2011) and, importantly, sometimes they do not retain their native structures (Butz et al. 2014). These problems often limit the utilization of artificially evolved protein binders in practical applications. Accordingly, alternative protein design techniques are required for creating artificial PPIs. Here we review recent progress in the rational design of de novo PPIs and describe the feasibility of the use of α-helices as the interfaces in de novo interactions.

Computational PPI design

Design of an interface that binds to a target protein

Recent progress in computational algorithm development allows in silico design of interfaces with high chemical and shape complementarities which are important for generating de novo PPIs. This approach consists of two steps: (1) searching for the best configuration of a pair of proteins that interact with each other and (2) optimization of the amino acid sequences of the proteins to produce the lowest energy in the bound state.

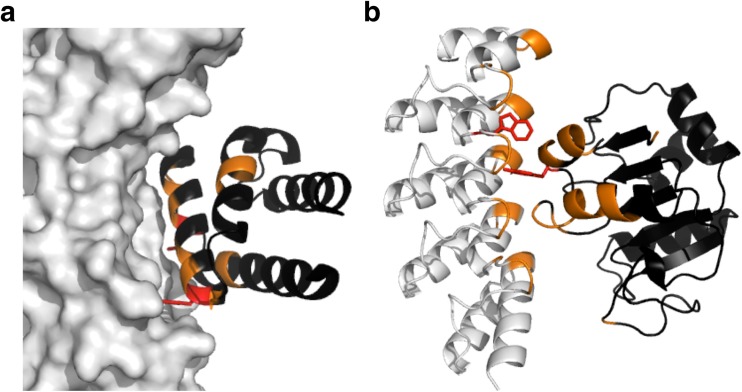

For naturally occurring protein complexes, a small number of residues located at the interfaces are critical for stabilizing the interaction between the subunits. These residues are called “hot-spots” (Bogan and Thorn 1998; Clackson and Wells 1995). A number of studies have used “hot-spot-centric-design” that grafts hot-spot residues found in a naturally occurring protein complex to a designed interface, followed by computational sequence optimization for better side chain packing over the entire interface area (Fig. 1a; Azoitei et al. 2011; Fleishman et al. 2011; Azoitei et al. 2012, 2014; Whitehead et al. 2012; Procko et al. 2013, 2014; Berger et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017; Strauch et al. 2017; Chevalier et al. 2017).

Fig. 1.

A computationally designed protein–protein interface (PPI). a The structure of the complex (PDB ID 3R2X) of a designed monomeric protein, APC36109 (black), and its target protein, hemagglutinin (white). The interface on APC36109 was designed by “hot-spot-centric-design” (Fleishman et al. 2011). The residues shown in red and orange indicate the grafted hot-spot residues and the computationally optimized residues, respectively. b The heterodimer (PDB ID 3Q9N) of an ankyrin repeat protein (white) and a coenzyme A binding protein (black). Both interfaces were created by computational design followed by directed evolution (Karanicolas et al. 2011). The residues shown in red indicate the grafted hot-spot residues, and the residues optimized by computational design and directed evolution are in orange

An alternative approach is called “dock-and-design”. In this method, a docked structure of a scaffold protein and its target is first simulated and then the sequence of the scaffold protein is optimized in order to generate the lowest energy interface that can bind to the target protein. Unlike “hot-spot-centric-design”, “dock-and-design” does not require any knowledge of the hot-spot residues (Jha et al. 2010; Procko et al. 2013). However, in one of the examples of this method a protein modified by “dock-and-design” bound to its target protein with very low affinity (Jha et al. 2010). More problematically, in another example, the modified protein bound to a surface other than the targeted site (Procko et al. 2013). Thus, the “dock-and-design” approach has not worked well to date.

Design of two interacting interfaces

Heterodimers have also been computationally designed by co-optimizing both interfaces (Huang et al. 2007; Karanicolas et al. 2011). Karanicolas et al. (2011) created a novel interaction between an ankyrin repeat protein and a monomeric coenzyme A-binding protein. Tyrosine and tryptophan residues were introduced into the center of the interfaces of both proteins as hot-spot residues, followed by sequence optimization around these residues using the Rosetta Design protocol (Leaver-Fay et al. 2011) (Fig. 1b). After experimental affinity maturation, the designed proteins formed a heterodimer with a dissociation constant (K D) value of 180 pM. However, the crystal structure showed that the mutant of the coenzyme A-binding protein was rotated 180° relative to the designed model (Karanicolas et al. 2011). To our knowledge, no other example has been reported of the successful design of a heterodimer by co-optimizing both interfaces. Thus, even with the use of a significant amount of computational design, it is still difficult to construct an artificial interaction between two arbitrary proteins.

Design of helix–helix interactions

Design of interactions between helical peptides

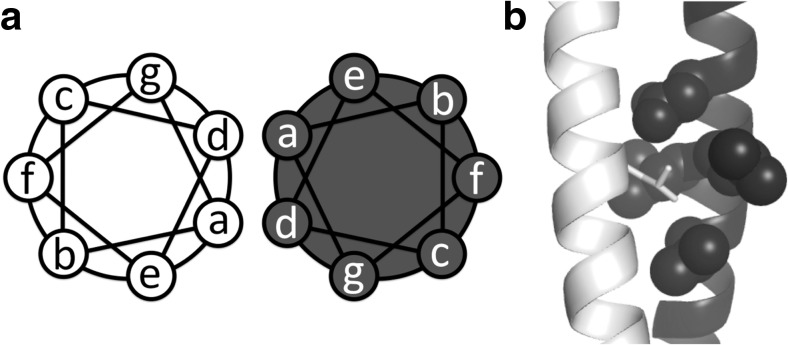

A protein structure consisting of two or more α-helices arranged in parallel or antiparallel is called a coiled-coil, and such proteins are frequently found in naturally occurring proteins. Indeed, the coiled-coil structure is found in up to 10% of all proteins from various organisms (Liu and Rost 2001; Rose et al. 2005; Rackham et al. 2010). The sequence–structure relationship of coiled-coils is well understood. In a canonical coiled-coil, two α-helices are arranged at an angle of 20° from the parallel alignment. The conformation of the coiled-coil can be represented as a repeat of a seven-amino acid unit (Fig. 2a). The positions within the unit are denoted as a–b–c–d–e–f–g, where the a and d positions are mainly occupied by hydrophobic residues and the remaining positions are often occupied by polar residues. When hydrophobic side chains at positions a and d are involved in inter-helical interactions, they participate in knob-into-hole packing; the hydrophobic sidechain (knob) of the residue at the a or d position is inserted into the hole formed by four hydrophobic sidechains in the other α-helix (Woolfson 2017) (Fig. 2b). In addition, charged amino acids are often located at positions e and g and form inter-helical salt bridges (Woolfson 2017). Based on this knowledge of the coiled-coil, helical peptides have been modified to drive homo-oligomerization of proteins (Woolfson 2017).

Fig. 2.

a A canonical two-helix coiled-coil is shown as a helical wheel model. The helix has a heptad-residue pattern from a to g. The residues at the a and d positions are usually hydrophobic. b The hydrophobic side chain of a residue at the a or d position of a helix, leucine in the stick model, projects into the hole formed by one a, one g, and two d side chains of the other helix (shown as spheres)

Knowledge of the sequence–structure relationship of the coiled-coil has been used to develop coiled-coil modeling programs (Grigoryan and Degrado 2011; Huang et al. 2014; Wood et al. 2014; Wood and Woolfson 2017). Notably, CCbuilder developed by the Woolfson group is a useful web-based tool for building and designing coiled-coil assemblies (Wood et al. 2014). In this program, a coiled-coil backbone is generated with input parameters such as number of polypeptide chains and geometric scores by modified mathematical parameterization derived from Crick’s original coiled-coil modeling equation (Crick 1953). Based on the backbone model, the ideal amino acid sequence is generated by the modified Rosetta program (Leaver-Fay et al. 2011). Indeed, the program has generated coiled-coil models that exactly match the reported crystal structures (Wood et al. 2014; Wood and Woolfson 2017). CCBuilder has high usability and can be used by non-specialist users for coiled-coil modeling and design.

Geometrical considerations of heptad repeats and CCBuilder were used by Thomson et al. (2014) to model an oligomeric coiled-coil structure. Out of 22 experimentally tested designs, two self-assembled into a tetramer, four into a pentamer, six into a hexamer and one into a heptamer. The crystal structures of a pentamer, two hexamers and the heptamer were confirmed to be similar to the modeled structures.

Therefore, with a deep understanding of the sequence–structure relationship of the coiled-coil structure and computational modeling programs, the design of simple helix–helix interactions is relatively easy. It is anticipated that much more complex coiled-coil architectures, such as assemblies with multiple helices and different orientations of helices, will be successfully designed in the future.

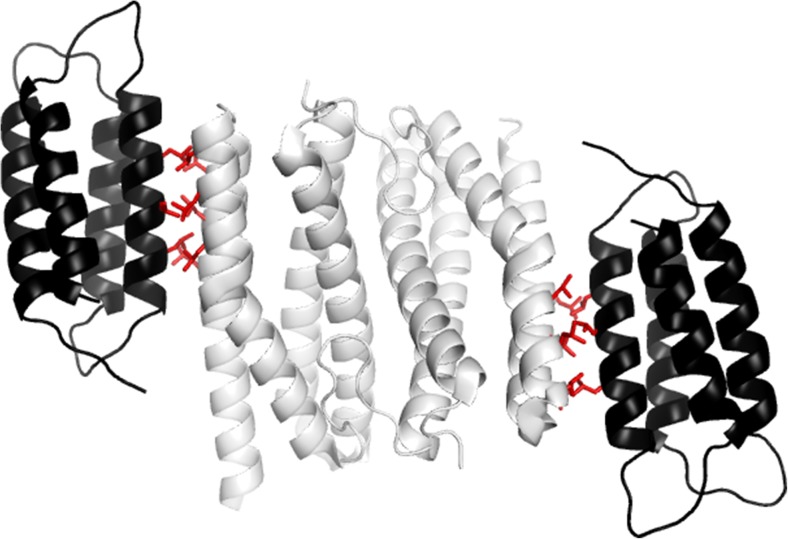

Design of PPIs mediated by inter-helical interactions

Helix–helix interactions are frequently observed at the interfaces of naturally occurring protein complexes. Guharoy and Chakrabarti demonstrated that 22.4% of homodimers and 10.9% of heterodimers have inter-molecular helix–helix interactions (Guharoy and Chakrabarti 2007). Similarly, helix–helix interactions across the interfaces were also found in a number of de novo designed protein complexes based on computational methods (Huang et al. 2007; Salgado et al. 2010; Fleishman et al. 2011; Mou et al. 2015a, b; Boyken et al. 2016; Fallas et al. 2016). In addition, several artificial proteins that contain intra-molecular helix–helix interactions have been constructed (Brunette et al. 2015; Doyle et al. 2015; Jacobs et al. 2016). Furthermore, helical structures are thought to be more tolerant of mutations than β-sheet and coils (Abrusán and Marsh 2016). For these reasons, exposed α-helices may be good targets for the creation of novel binding interfaces for artificial PPIs. Furthermore, because α-helices are often located on protein surfaces, designing an inter-helical interaction-mediated PPI is a useful approach for creating de novo protein complexes. With the above in mind we have generated PPIs through modification of exposed α-helices. We engineered the exposed α-helices of two helical bundle proteins, a dimeric sulerythrin and a monomeric cysLARFH (Fig. 3) (Yagi et al. 2016). Six leucine residues and six aspartate or glutamate residues were introduced onto the surface formed by two anti-paralleled α-helices of sulerythrin. In addition, three leucine residues and three lysine or arginine residues were introduced into an α-helix of cysLARFH. We hypothesized that the two modified proteins would interact with each other through formation of a intermolecular three-helix bundle. Indeed, these protein mutants form a hetero-tetramer (cysLARFH monomer/sulerythrin dimer/cysLARFH monomer (Fig. 3) with a K D value of 160 nM. This result indicates that an artificial PPI can be generated by the simple approach of creating de novo interfaces on α-helices. However, we should point out that the crystal structure of the heterotetramer has not yet been determined.

Fig. 3.

The modeled structure of the designed complex between homodimeric sulerythrin (white) and two monomeric cysLARFHs molecules (black). The interaction between the proteins was created by modification of the sequences of their exposed α-helices (Yagi et al. 2016). The image was generated from the crystal structures of sulerythrin (PDB ID 1 J30) and the four-helix bundle domain of the lac repressor (PDB ID 3EDC) from which cysLARFH was derived. The introduced Leu residues at the interfaces of sulerythrin and cysLARFH are shown as red sticks

An artificial interaction between β-strands has also been reported. Two copies of a monomeric protein, which has an unpaired β-strand on its surface, were computationally docked to generate a homodimer through intermolecular strand–strand interactions of hydrogen bonds (Stranges et al. 2011). The amino acids surrounding the β-strands were then energetically optimized with the Rosetta Design program. However, empirical testing showed that only one out of ten designs formed a homodimeric structure as expected. As far as we are aware, the aforementioned study is the sole successful example of the creation of an artificial homodimer using β-strands as the subunit interface. As such, the design of interfaces on α-helices—rather than on β-strands—is currently considered to be the more promising approach.

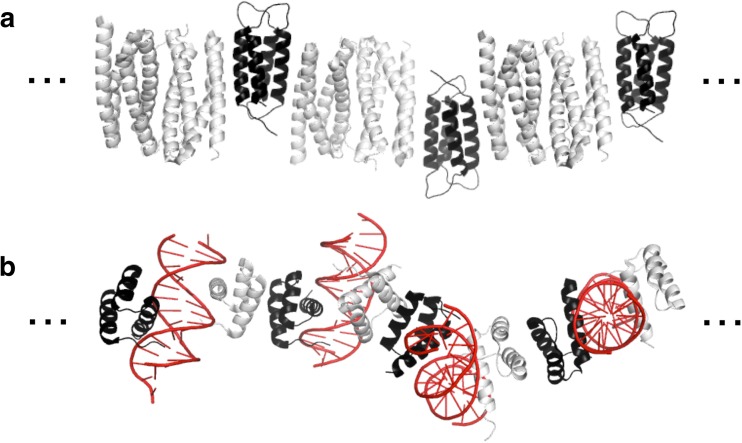

Construction of an artificial peptide fiber using helix–helix interactions

Helix–helix interactions have also been used to construct fibrous structures. Woolfson and coworkers developed a novel fiber using two complementary 28-residue helical peptides, SAF-p1 and SAF-p2 (Pandya et al. 2000). Interaction between the two peptides induced the formation of staggered heterodimers. The resulting heterodimers had “sticky-ends” that further induced the formation of fibers (Fig. 4a). Upon mixing SAF-p1 and SAF-p2, fibrous structures several tens of micrometers in length and several tens of nanometers in width were produced.

Fig. 4.

The modeled structures of α-helical peptide fibers. a The fiber comprised two complementary helical peptides (Pandya et al. 2000). The image was generated based on the crystal structures of the SAF peptide (PDB ID 3RA3). b The tube-like fiber was created by modification of the termini of the α-helical barrel proteins (Burgess et al. 2015). The hydrophobic lumen is shown in the right image. The images were generated based on the crystal structure of the α-helical barrel protein (PDB ID 4PNA). The hydrophobic residues in the lumen are shown as red sticks. c The self-assembled cylindrical structure formed by association of the two offset hydrophobic faces of an α-helical peptide, determined by electron cryo-microscopy (PDB ID 3 J89) (Egelman et al. 2015). The lumen is shown in the right image. The hydrophobic residues at the two interfaces of the helix are shown as red sticks

In other studies, tube-like coiled-coil fibers were constructed using α-helical barrels that contain a cavity in the hydrophobic core (Xu et al. 2013; Hume et al. 2014; Burgess et al. 2015). In the Burgess et al. (2015) study, three kinds of natural barrel-like coiled-coil proteins, each of which consisted of five, six or seven helical peptides with four-heptad repeat sequences, were engineered to assemble into tube-like structures through end-to-end associations (Fig. 4b). The peptides were modified to expose patches of hydrophobic core near the N-termini which could interact with the hydrophobic core at the C-termini of the neighboring molecule. In addition, charged residues (E or K) were placed at the C-termini to electrically bind to oppositely charged side chains in the N-terminal heptad repeats. The tubes contained a hydrophobic channel that was accessible by small hydrophobic dyes (Fig. 4b) (Burgess et al. 2015). These results demonstrated the generality of this strategy for constructing tube-like structures using α-helical barrels.

Coiled-coil tubes with a larger diameter of lumen were designed by Egelman and coworkers. In their design, the synthesized 29-residue α-helical peptide, which had two interfaces formed by hydrophobic residues at positions a, d, c and f, self-assembled into a cylindrical α-helical assembly that contained a lumen with a radius of a few nanometers (Fig. 4c) (Egelman et al. 2015).

Thus, several fiber and tube structures have been constructed by designing interactions between helical peptides. The well-established design method for helical peptide fiber construction may confer advantages for applications in bio-nanotechnology, such as the construction of scaffolds for nano-scale electronic circuits or in targeted drug delivery systems.

Construction of artificial protein fibers through helix–helix interactions

We have also engineered a modified version of cysLARFH where two hydrophobic surfaces were created on two opposite surfaces. The hydrophobic surfaces could serve as interfaces for interacting with other protein molecules that also have a hydrophobic surface. When the cysLARFH variant and the sulerythrin mutant, each with the designed hydrophobic interface, were mixed, thin fibers were observed by atomic force microscopy (Fig. 5a) (Yagi et al. 2016). The average length of the self-assembled fibers was 90 nm. Therefore, the generation of PPIs through helix–helix interactions can be applied to fiber development. However, branching structures within the fibers were observed, possibly due to undesired interactions at surfaces other than the designed interfaces.

Fig. 5.

a The modeled structure of artificial protein fibers. The fiber comprised sulerythrin homodimers (white) and cysLARFH monomers (black) (Yagi et al. 2016). b The crystal structure of a protein–DNA hybrid fiber (PDB ID 4QTR) (Mou et al. 2015b)

Mayo’s group has computationally designed co-assembled a protein-DNA fiber (Fig. 5b) (Mou et al. 2015b). In this work, a monomeric DNA binding protein was engineered to assemble into a homodimer via inter-molecular helix–helix interactions. The resulting dimer displayed DNA binding motifs at both ends. By mixing the protein and a double-stranded DNA fragment that contained two protein-binding sequences, fibers formed spontaneously. Atomic force microscopy demonstrated clear, fibrous structures with a length of up to ~ 300 nm. Thus, the PPI design method with DNA binding produced a protein–DNA hybrid fiber by using the DNA as glue.

While the designs of the protein-based and protein/DNA-based fibers described above were successful, the length of the constructed fibers was shorter than that of natural fibrous proteins such as actin. One way to address this would be to enhance the affinity of the PPI which induces one-directional polymerization of proteins, as is the strategy taken with the formation of natural fibrous proteins.

Construction of a more complex structure

Self-assembling complexes designed using a computational PPI design strategy

The symmetric docking strategy has been used multiple times to create homo-oligomers. In this strategy, docking is performed using the following steps: (1) multiple copies of a protein are symmetrically arranged in silico; (2) all protein molecules are allowed to rotate around the symmetry axis of the oligomer and also to move along the axis; (3) the suitability of the docked configurations is assessed by measuring the buried area of the interfaces and by scoring complementarity. The symmetric docking strategy has generated symmetric oligomers, including dimers (Fig. 6a), trimers (Fig. 6b), tetramers (Fig. 6c), pentamers, hexamers, 12-mers, 24-mers (Fig. 6d), 60-mers and 2-dimensional arrays (Stranges et al. 2011; King et al. 2012; Der et al. 2012; Gonen et al. 2015; Mou et al. 2015a, b; Boyken et al. 2016; Fallas et al. 2016; Hsia et al. 2016; Mills et al. 2016). For example, King and Bare applied the symmetrical docking method to generate heteromeric protein complexes (King et al. 2014; Bale et al. 2016). Two types of engineered homo-oligomers, such as dimers, trimers or pentamers, formed several cage-like structures when the two proteins were mixed (Fig. 6e, f). In these studies, the high-resolution crystal structures of the complexes showed good agreement with their computational models at atomic level.

Fig. 6.

Crystal structures of computationally designed homo-oligomers. a–c The dimer (PDB ID 5HSY), trimer (5HEZ) and tetramer (5HS0) were designed by Fallas and coworkers (Fallas et al. 2016). d The homotrimeric protein was engineered to form a cage-like, 24-mer complex by King and coworkers (PDB ID 4DDF) (King et al. 2012). e Two trimeric proteins, shown in white and black, were engineered to form a cage-like, hetero-24-mer by King and coworkers (PDB ID 4DDF) (King et al. 2014). f The pentameric protein (black) and the trimeric protein (white) were engineered to form a cage-like, hetero-120-mer by Bale and coworkers (PDB ID 5IM5) (Bale et al. 2016)

These several successful examples indicate the substantial potential of the symmetrical docking method for construction of novel protein oligomers. However, the success rates for assembly are generally low (~ 15%), likely due to the fact that current protein modeling and sequence design techniques do not take into account all of the factors that induce PPIs between any two proteins.

Self-assembling complexes designed by combination of coiled-coil motifs

helix–helix interactions have also been used to construct cage-like structures. Gradišar et al. created a tetrahedron-forming polypeptide chain comprising 12 concatenated coiled-coil-forming segments separated by flexible tetra-peptide linkers (Gradisar et al. 2013). Folding was driven by specific pairwise interactions between different coiled-coil elements within the polypeptide. In this design strategy the use of multiple coiled-coil forming segments to extend to additional polyhedral architecture (for example, to an octahedron) would be challenging. However, to this end, over 12 different coiled-coil segments have been concatenated into a single polypeptide chain. However, the resulting polypeptide seems to misfold due to nonspecific interactions between helix-forming segments within a single polypeptide. Therefore, great care needs to be taken in the selection of coiled-coil dimers when designing a larger polyhedron.

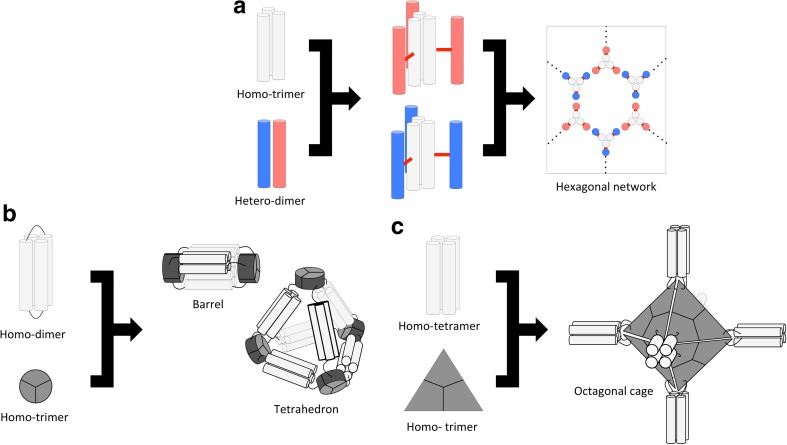

Fletcher et al. developed a novel method for creating self-assembled cage-like particles using a homotrimeric coiled-coil (CC-Tri3) and a heterodimeric coiled-coil (CC-Di-AB). In their study, the helical peptide that formed CC-Tri3 was linked to another helical peptide CC-Di-A or CC-Di-B through their external helical faces via a disulfide-bond, yielding CC-Tri-3–CC-Di-A or CC-Tri-3–CC-Di-B. Both CC-Tri-3–CC-Di-A and CC-Tri-3–CC-Di-B spontaneously self-assembled into homotrimers, with the segment originating from CC-Tri3 driving trimer formation (Fig. 7a). When C-Tri-3–CC-Di-A and CC-Tri-3–CC-Di-B were mixed, the two chains assembled via an interaction between the CC-Di-A and CC-Di-B, thus forming hexagonal networks (Fig. 7a). Atomic force microscopy demonstrated that the hexagonal network formed mono-layer spheres with a diameter of approximately 100 nm (Fletcher et al. 2013). However, the size of the resulting sphere-like structures still cannot be predicted from the amino acid sequence due to the flexibility of the disulfide-linked coiled-coil forming peptides.

Fig. 7.

Schemes for designing cage-like structures. a The homotrimeric coiled-coil CC-Tri3 (white) and a subunit of the heterodimeric coiled coils CC-Di-AB (blue and pink) were linked with disulfide bonds (red lines) to yield two hub components. A hexagonal network was formed by mixing the two hub components (Fletcher et al. 2013). b A subunit of the homodimeric coiled coil (WA20, white) and a subunit of the homotrimeric protein (foldon, gray) were fused. The fused protein self-assembles into a barrel- or a tetrahedron-like cage structure (Kobayashi et al. 2015). c A subunit of the homotetrameric coiled-coil (CC-Tet, white) and a subunit of the homotrimeric esterase (gray) were fused. The fused protein self-assembles into an octahedron-like cage structure (Sciore et al. 2016)

Self-assembling complexes designed by the fusion of oligomeric proteins and coiled-coil proteins

Coiled-coil proteins, in combination with other proteins, have been used to construct more complex structures (Patterson et al. 2011, 2013; Kobayashi et al. 2015; Sciore et al. 2016). For example, Arai and coworkers created cage-like protein complexes (Kobayashi et al. 2015). In their design, a subunit of the homodimeric coiled-coil protein WA20 (Arai et al. 2012) was fused with a homotrimeric foldon domain of the T4 phage fibritin (Fig. 7b). The fused protein assembled into several homo-oligomeric forms. The molecular masses of the oligomers corresponded to the homohexamer, homododecamer and homooctadecamer. In addition, a small-angle X-ray scattering analysis revealed that the homohexamer and the homododecamer existed in barrel-like and tetrahedron-like structures, respectively (Fig. 7b) (Kobayashi et al. 2015).

In contrast to the aforementioned study by Arai and coworkers, Marsh’s group (Sciore et al. 2016) produced a more homogeneous assembly. These authors investigated the length of the peptide linker that connects a homotrimeric protein and a homotetrameric coiled-coil. The fused protein with a four-glycine linker predominately (~ 75%) self-assembled into a 24-mer (Fig. 7c). In addition, cryo-transmission electron microscopy analysis demonstrated that the protein complex forms a cage-like structure (Sciore et al. 2016). In contrast, the fused proteins linked by two contiguous glycines formed heterogeneous oligomers. When the proteins were linked by three glycine residues, the fused proteins formed insoluble aggregates. Therefore, in the case where a fused polypeptide chain is used as the unit of a de novo protein complex, the length of the linker may be an important factor in the production of a homogeneous protein assembly.

The fusion approach with coiled-coil proteins is a simple one for constructing symmetrical polyhedral cage structures. It does not require complicated de novo PPI design, so the structural specificity of the resulting assembly is mainly dependent on the linker peptide sequences between the coiled-coil-forming oligomer protein and the native oligomer protein. However, the approach has generally yielded heterogeneous assemblies. While Sciore et al. (2016) improved the homogeneity of the assemblies, they could not fully prevent unanticipated assembly. For further improvement of homogeneity of fused protein assemblies, rigidity (or flexibility) of the linker also needs to be taken into account, because it is known that the linker rigidity affect the orientations of the fused proteins (Argos 1990; Arai et al. 2001; George and Heringa 2002; Li et al. 2016).

Concluding remarks

In this review we have summarized the several routes to computationally designing de novo PPIs. However, the computational methods do not always create successful de novo PPIs and, therefore, more reliable methods remain to be established. The depth of our knowledge on the sequence–structure relationships of coiled-coils paves the way for reliable construction of inter-helical peptides interactions. In addition, inter-helical interactions are frequently found in native and computationally designed protein complexes. Thus, exposed α-helices are good targets for creating interfaces that induce de novo PPIs. In addition, the creation of PPIs contributes to the de novo design of protein fibers and higher-order supermolecular complexes.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K14494 to S.A. and by MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (S1512002), 2015–2017 to A.Y.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Sota Yagi declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Satoshi Akanuma declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Akihiko Yamagishi declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘Biomolecules to Bio-nanomachines—Fumio Arisaka 70th Birthday’ edited by Damien Hall, Junichi Takagi and Haruki Nakamura.

References

- Abrusán G, Marsh JA. Alpha helices are more robust to mutations than beta strands. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1005242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai R, Ueda H, Kitayama A, Kamiya N, Nagamune T. Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein. Protein Eng. 2001;14:529–532. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.8.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai R, Kobayashi N, Kimura A, Sato T, Matsuo K, Wang AF, Platt JM, Bradley LH, Hecht MH. Domain-swapped dimeric structure of a stable and functional de novo four-helix bundle protein, WA20. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:6789–6797. doi: 10.1021/jp212438h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argos P. An investigation of oligopeptides linking domains in protein tertiary structures and possible candidates for general gene fusion. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:943–958. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90085-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoitei ML, Correia BE, Ban YE, Carrico C, Kalyuzhniy O, Chen L, Schroeter A, Huang PS, McLellan JS, Kwong PD, Baker D, Strong RK, Scief WR. Computation-guided backbone grafting of a discontinuous motif onto a protein scaffold. Science. 2011;334:373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1209368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoitei ML, Ban YE, Julien JP, Bryson S, Schroeter A, Kalyuzhniy O, Porter JR, Adachi Y, Baker D, Pai EF, Schoef WR. Computational design of high-affinity epitope scaffolds by backbone grafting of a linear epitope. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:175–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoitei ML, Ban YA, Kalyuzhny O, Guenaga J, Schroeter A, Porter J, Wyatt R, Schief WR. Computational design of protein antigens that interact with the CDR H3 loop of HIV broadly neutralizing antibody 2F5. Proteins. 2014;82:2770–2782. doi: 10.1002/prot.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale JB, Gonen S, Liu Y, Sheffler W, Ellis D, Thomas C, Cascio D, Yeates TO, Gonen T, King NP, Baker D. Accurate design of megadalton-scale two-component icosahedral protein complexes. Science. 2016;353:389–394. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S, Procko E, Margineantu D, Lee EF, Shen BW, Zelter A, Silva DA, Chawla K, Herold MJ, Garnier JM, Johnson R, MacCoss MJ, Lessene G, Davis TN, Stayton PS, Stoddard BL, Fairlie WD, Hockenbery DM, Baker D. Computationally designed high specificity inhibitors delineate the roles of BCL2 family proteins in cancer. elife. 2016;5:e20352. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan AA, Thorn KS. Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyken SE, Chen Z, Groves B, Langan RA, Oberdorfer G, Ford A, Gilmore JM, Xu C, DiMaio F, Pereira JH, Sankaran B, Seelig G, Zwart PH, Baker D. De novo design of protein homo-oligomers with modular hydrogen-bond network-mediated specificity. Science. 2016;352:680–687. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette TJ, Parmeggiani F, Huang PS, Bhabha G, Ekiert DC, Tsutakawa SE, Hura GL, Tainer JA, Baker D. Exploring the repeat protein universe through computational protein design. Nature. 2015;528:580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature16162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess NC, Sharp TH, Thomas F, Wood CW, Thomson AR, Zaccai NR, Brady RL, Serpell LC, Woolfson DN. Modular design of self-assembling peptide-based nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10554–10562. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz M, Kast P, Hilvert D. Affinity maturation of a computationally designed binding protein affords a functional but disordered polypeptide. J Struct Biol. 2014;185:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier A, Silva DA, Rocklin GJ, Hicks DR, Vergara R, Murapa P, Bernard SM, Zhang L, Lam KH, Yao G, Bahl CD, Miyashita SI, Goreshnik I, Fuller JT, Koday MT, Jenkins CM, Colvin T, Carter L, Bohn A, Bryan CM, Fernández-Velasco DA, Stewart L, Dong M, Huang X, Jin R, Wilson IA, Fuller DH, Baker D (2017) Massively parallel de novo protein design for targeted therapeutics. Nature 550:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature23912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chin JW, Schepartz A. Design and evolution of a miniature Bcl-2 binding protein. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:3806–3809. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3806::AID-ANIE3806>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clackson T, Wells JA. A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone–receptor interface. Science. 1995;267:383–386. doi: 10.1126/science.7529940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FHC. The packing of alpha-helices–simple coiled-coils. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:689–697. doi: 10.1107/S0365110X53001964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Der BS, Machius M, Miley MJ, Mills JL, Szyperski T, Kuhlman B. Metal-mediated affinity and orientation specificity in a computationally designed protein homodimer. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:375–385. doi: 10.1021/ja208015j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L, Hallinan J, Bolduc J, Parmeggiani F, Baker D, Stoddard BL, Bradley P. Rational design of α-helical tandem repeat proteins with closed architectures. Nature. 2015;528:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature16191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelman EH, Xu C, DiMaio F, Magnotti E, Modlin C, Yu X, Wright E, Baker D, Conticello VP. Structural plasticity of helical nanotubes based on coiled-coil assemblies. Structure. 2015;23:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallas JA, Ueda G, Sheffler W, Nguyen V, McNamara DE, Sankaran B, Pereira JH, Parmeggiani F, Brunette TJ, Cascio D, Yeates TR, Zwart P, Baker D. Computational design of self-assembling cyclic protein homo-oligomers. Nat Chem. 2016;9:353–360. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman SJ, Whitehead TA, Ekiert DC, Dreyfus C, Corn JE, Strauch E, Wilson IA, Baker D. Computational design of proteins targeting the conserved stem region of influenza hemagglutinin. Science. 2011;332:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1202617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Harniman RL, Barnes FRH, Boyle AL, Collins A, Mantell J, Sharp TH, Antognozzi M, Booth PJ, Linden N, Miles MJ, Sessions RB, Verkade P, Woolfson DN. Self-assembling cages from coiled-coil peptide modules. Science. 2013;340:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.1233936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemperli AC, Rutledge SE, Maranda A, Gemperli AS. Paralog-selective ligands for Bcl-2 proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1596–1597. doi: 10.1021/ja0441211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George RA, Heringa J. An analysis of protein domain linkers: their classification and role in protein folding. Protein Eng. 2002;15(11):871–879. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.11.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonen S, Dimaio F, Gonen T, Baker D. Design of ordered two-dimensional arrays mediated by noncovalent protein–protein interfaces. Science. 2015;348:1365–1368. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradisar H, Bozic S, Doles T, Vengust D, Hafner-Bratkovic I, Mertelj A, Webb B, Sali A, Klavzar S, Jerala R. Design of a single-chain polypeptide tetrahedron assembled from coiled-coil segments. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan G, Degrado WF. Probing designability via a generalized model of helical bundle geometry. J Mol Biol. 2011;405:1079–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guharoy M, Chakrabarti P. Secondary structure based analysis and classification of biological interfaces: identification of binding motifs in protein–protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1909–1918. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia Y, Bale JB, Gonen S, Shi D, Sheffler W, Fong KK, Nattermann U, Xu C, Huang PS, Ravichandran R, Yi S, Davis TN, Gonen T, King NP, Baker D. Design of a hyperstable 60-subunit protein icosahedron. Nature. 2016;535:136–139. doi: 10.1038/nature18010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PS, Love JJ, Mayo SL. A de novo designed protein protein interface. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2770–2774. doi: 10.1110/ps.073125207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PS, Oberdorfer G, Xu CF, Pei XY, Nannenga BL, Rogers JM, DiMaio F, Gonen T, Luisi B, Baker D. High thermodynamic stability of parametrically designed helical bundles. Science. 2014;346:481–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1257481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume J, Sun J, Jacquet R, Renfrew PD, Martin JA, Bonneau R, Gilchrist ML, Montclare JK. Engineered coiled-coil protein microfibers. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3503–3510. doi: 10.1021/bm5004948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäckel C, Kast P, Hilvert D. Protein design by directed evolution. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:153–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs TM, Williams B, Williams T, Xu X, Eletsky A, Federizon JF, Szyperski T, Kuhlman B. Design of structurally distinct proteins using strategies inspired by evolution. Science. 2016;352:687–690. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha RK, Leaver-Fay A, Yin S, Wu Y, Butterfoss GL, Szyperski T, Dokholyan NV, Kuhlman B. Computational design of a PAK1 binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanicolas J, Corn J, Chen I, Joachimiak L, Dym O, Peck S, Albeck S, Unger T, Hu W, Liu G, Debecq S, Montelione GT, Spiegel CP, Liu DR, Baker D. A de novo protein binding pair by computational design and directed evolution. Mol Cell. 2011;42:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NP, Sheffler W, Sawaya MR, Vollmar BS, Sumida JP, Andre I, Gonen T, Yeates TO, Baker D. Computational design of self-assembling protein nanomaterials with atomic level accuracy. Science. 2012;336:1171–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1219364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NP, Bale JB, Sheffler W, McNamara DE, Gonen S, Gonen T, Yeates TO, Baker D. Accurate design of co-assembling multi-component protein nanomaterials. Nature. 2014;510:103–108. doi: 10.1038/nature13404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Yanase K, Sato T, Unzai S, Hecht MH, Arai R. Self-assembling Nano-architectures created from a protein Nano-building block using an Intermolecularly folded Dimeric de novo protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11285–11293. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaver-Fay A, Tyka M, Lewis SM, Lange OF, Thompson J, Jacak R, Kaufman K, Renfrew PD, Smith CA, Sheffler W, Davis IW, Cooper S, Treuille A, Mandell DJ, Richter F, Ban YE, Fleishman SJ, Corn JE, Kim DE, Lyskov S, Berrondo M, Mentzer S, Popović Z, Havranek JJ, Karanicolas J, Das R, Meiler J, Kortemme T, Gray JJ, Kuhlman B, Baker D, Bradley P. ROSETTA3: an object-oriented software suite for the simulation and design of macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 2011;487:545–574. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381270-4.00019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Huang Z, Zhang C, Dong BJ, Guo RH, Yue HW, Yan LT, Xing XH. Construction of a linker library with widely controllable flexibility for fusion protein design. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:215–225. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JF, Rost B. Comparing function and structure between entire proteomes. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1970–1979. doi: 10.1110/ps.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Taylor RD, Griffin L, Coker SF, Adams R, Ceska T, Shi J, Lawson ADG, Baker T. Computational design of an epitope-specific Keap1 binding antibody using hotspot residues grafting and CDR loop swapping. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41306. doi: 10.1038/srep41306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus JJ, Charbonneau P, Zaccarelli E (2016) The physics of protein self-assembly. Cur Opin Colloid Interface Sci 22:73–79

- Mills JH, Sheffler W, Ener ME, Almhjell PJ, Oberdorfer G, Pereira JH, Parmeggiani F, Sankaran B, Zwart PH, Baker D. Computational design of a homotrimeric metalloprotein with a trisbipyridyl core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:15012–15017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600188113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Y, Huang PS, Hsu FC, Huang SJ, Mayo SL. Computational design and experimental verification of a symmetric protein homodimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10714–10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505072112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Y, Yu JY, Wannier TM, Guo CL, Mayo SL. Computational design of co-assembling protein-DNA nanowires. Nature. 2015;525:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature14874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya MJ, Spooner GM, Sunde M, Thorpe JR, Rodger A, Woolfson DN. Sticky-end assembly of a designed peptide fiber provides insight into protein fibrillogenesis. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8728–8734. doi: 10.1021/bi000246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DP, Desai AM, Holl MM, Marsh EN. Evaluation of a symmetry-based strategy for assembling protein complexes. RSC Adv. 2011;1:1004–1012. doi: 10.1039/c1ra00282a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DP, Su M, Franzmann TM, Sciore A, Skiniotis G, Marsh EN. Characterization of a highly flexible self-assembling protein system designed to form nanocages. Protein Sci. 2013;23:190–199. doi: 10.1002/pro.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procko E, Hedman R, Hamilton K, Seetharaman J, Fleishman SJ, Su M, Aramini M, Kornhaber G, Hunt JF, Tong L, Montelione GT, Baker D. Computational design of a protein-based enzyme inhibitor. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3563–3575. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procko E, Berguig GY, Shen BW, Song Y, Frayo S, Convertine AJ, Margineantu D, Booth G, Correia BE, Cheng Y, Schief WR, Hockenbery DM, Press OW, Stoddard BL, Stayton PS, Baker D. A computationally designed inhibitor of an Epstein–Barr viral Bcl-2 protein induces apoptosis in infected cells. Cell. 2014;157:1644–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackham OJL, Madera M, Armstrong CT, Vincent TL, Woolfson DN, Gough J. The evolution and structure prediction of coiled coils across all genomes. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:480–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A, Schraegle SJ, Stahlberg EA, Meier I. Coiled-coil protein composition of 22 proteomes-differences and common themes in subcellular infrastructure and traffic control. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado EN, Ambroggio XI, Brodin JD, Lewis RA, Kuhlman B, Tezcan FA (2010) Metal templated design of protein interfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:1827–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sciore A, Su M, Koldewey P, Eschweiler JD, Diffley KA, Linhares BM, Ruotolo BT, Bardwell JC, Skiniotis G, Marsh EN. Flexible, symmetry-directed approach to assembling protein cages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606013113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranges PB, Machius M, Miley MJ, Tripathy A, Kuhlman B. Computational design of a symmetric homodimer using beta-strand assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20562–20567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115124108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauch EM, Bernard SM, La D, Bohn AJ, Lee PS, Anderson CE, Nieusma T, Holstein CA, Garcia NK, Hooper KA, Ravichandran R, Nelson JW, Sheffler W, Bloom JD, Lee KK, Ward AB, Yager P, Fuller DH, Wilson IA, Baker D. Computational design of trimeric influenza-neutralizing proteins targeting the hemagglutinin receptor binding site. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AR, Wood CW, Burton AJ, Bartlett GJ, Sessions RB, Brady RL, Woolfson DN (2014) Computational design of water-soluble α-helical barrels. Science 346:485–488 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Whitehead TA, Chevalier A, Song Y, Dreyfus C, Fleishman SJ, De Mattos C, Myers CA, Kamisetty H, Blair P, Wilson IA, Baker D. Optimization of affinity, specificity and function of designed influenza inhibitors using deep sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CW, Woolfson DN (2017) CCBuilder 2.0: powerful and accessible coiled-coil modeling. Protein Sci. doi:10.1002/pro.3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wood CW, Bruning M, Ibarra AA, Bartlett GJ, Thomson AR, Sessions RB, Brady RL, Woolfson DN. CCBuilder: an interactive web-based tool for building, designing and assessing coiled-coil protein assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3029–3035. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfson DN. Coiled-coil design: updated and upgraded. Subcell Biochem. 2017;82:35–61. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-49674-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Liu R, Mehta AK, Guerrero-Ferreira RC, Wright ER, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Morris K, Serpell LC, Zuo X, Wall JS, Conticello VP. Rational design of helical nanotubes from self-assembly of coiled-coil lock washers. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15565–15578. doi: 10.1021/ja4074529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, Akanuma S, Yamagishi M, Uchida T, Yamagishi A. De novo design of protein–protein interactions through modification of inter-molecular helix–helix interface residues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Zhang C, Zhang T, Zhang X, Shen Q, Tang B, Liang H, Lai L. Rational design of TNFa binding proteins bas ed on the de novo designed protein DS119. Prot Sci. 2016;25:2066–2075. doi: 10.1002/pro.3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]