Abstract

Cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) in association with a single particle analysis method (SPA) is now a promising tool to determine the structures of proteins and their macromolecular complexes. The development of direct electron detection cameras and image processing technologies has allowed the structures of many important proteins to be solved at near-atomic resolution or, in some cases, at atomic resolution, by overcoming difficulties in crystallization or low yield of protein production. In the case of membrane-integrated proteins, the proteins were traditionally solubilized and stabilized with various kind of detergents. However, the density of detergent micelles diminished the contrast of membrane proteins in cryo-EM studies and made it difficult to obtain high-resolution structures. To improve the resolution of membrane protein structures in cryo-EM studies, major improvements have been made both in sample preparation techniques and in hardware and software developments. The focus of our review is on improvements which have been made in the various techniques for sample preparation for cryo-EM studies, with a specific interest placed on techniques for mimicking the lipid environment of membrane proteins.

Keywords: Cryoelectron microscopy, Membrane proteins, Single particle analysis, Lipid environment

Introduction

Cells and various organelles contain biological membranes that shape them and support various biological activities. Proteins integrated in membranes play important roles, such as transmembrane trafficking, cell sensing and signaling, gas exchange, and energy synthesis. In the genome of all organisms, almost 20–30% of genes encode membrane proteins (Krogh et al. 2001; Wallin and Heijne 1998), and chemicals and natural compounds that control the function of membrane proteins are actively being searched for as new drug candidates. Indeed, 50–60% of drugs on the market target membrane proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels (Drews 2000; Overington et al. 2006; Terstappen and Reggiani 2001).

Structural information on membrane proteins is indispensable for understanding biological mechanisms and designing active drugs starting from their lead compounds. However, the highly hydrophobic nature of transmembrane domains causes intolerable difficulties in the sample preparation steps. Indeed, determination of the three-dimensional (3-D) structure of membrane proteins was previously considered a waste of both time and effort and cost-consuming. As such progress made on membrane proteins using this technique has been much delayed, in contrast to that of water-soluble proteins.

In recent years, a new generation of direct electron detection cameras for electron microscopy (McMullan et al. 2014) and image processing software implemented with the Bayesian approach (Kimanius et al. 2016; Scheres 2012) have been developed in parallel. Due to these novel developments, as well as the establishment of big data handling techniques, the resolution of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) with single particle analysis (SPA) methods has been drastically improved. Cryo-EM with SPA does not require crystallization, which has long been a bottleneck for structural determination of membrane proteins. Cryo-EM obtains a 3-D structure by information processing technology from photographic particle images of proteins that have been quickly frozen and embedded in amorphous ice.

Over the past 5 years, the structures of important membrane protein complexes, which are difficult to crystallize, have been determined by the cryo-EM technique. Starting from high-resolution analyses of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (Liao et al. 2013; Paulsen et al. 2015) and γ-secretase (Bai et al. 2015; Lu et al. 2014), structures of various membrane proteins have been revealed by cryo-EM studies. These include other subtypes of TRP channels (Jin et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Paulsen et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2016; Zubcevic et al. 2016), voltage-gated channels (Guo et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2017; Whicher and MacKinnon 2016; Wu et al. 2016), and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017; Johnson and Chen 2017; Kim et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2017; Oldham et al. 2016; Qian et al. 2017; Taylor et al. 2017; Zhang and Chen 2016). Now, even the structures of G-protein-coupled receptors are becoming the target of cryo-EM (or a cryo-EM equipped with the Volta phase plate) (Liang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017). Readers will find an increasing number of examples in previously published excellent reviews (Baker et al. 2017; Mazhab-Jafari and Rubinstein 2016; Milenkovic et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2017; Zalk and Marks 2017; Zhu and Gouaux 2017). Most of these structures are solved at near-atomic resolution (3–4 Å), and in some cases, the electron densities of small ligands, associated lipids, water molecules, or metal ions were successfully defined, thereby providing useful information for the pharmacological design of new drugs and understanding of their mechanisms.

To improve the resolution of membrane protein structures in cryo-EM, sample preparation techniques have been (and have to be further) improved (Figs. 1, 2), although the main focus is on the development of hardware and software. In addition to the various applications of oftentimes solubilizing detergents, a number of modern preparation technologies, such as amphipols and nanodiscs, are necessary for visualization of the transmembrane helices of membrane proteins which were originally located in the lipid bilayer. Here we review the sample preparation techniques for visualizing transmembrane structures that are currently used for the recently strongly improved cryo-EM method.

Fig. 1.

Electron microscopy (EM) for structural biology. a Sample preparation for negative staining EM (left) and cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) (right). In this figure, membrane proteins (green) are associated with membrane lipids (red). b EM images of the hepatitis B small surface antigen: negative staining transmission EM image (left) and cryo-EM image (right). Bar: 100 nm

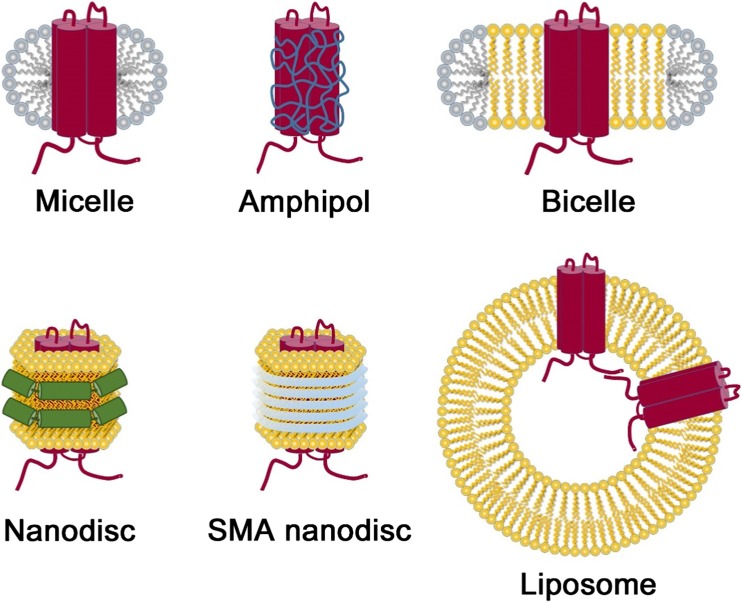

Fig. 2.

Structures of various artificial membranes. Solubilization of membrane proteins with detergents forms micelle structure. Hydrophobic acyl chains interact with the transmembrane surface of membrane proteins. Amphipathic polymer amphipoles are substituted with detergents to form a stable complex in solution. Bicelles are generated by mixing two components. Phospholipids with a long chain form interact with the protein and form a bilayer, and detergents with a short chain fill the rim of the disc. In the nanodisc, two membrane scaffold proteins assemble around detergent-solubilized membrane proteins with lipids to form disc shaped particles. Styrene–maleic acid (SMA) copolymers are polymer-based particles which cover the acyl chains of the lipid bilayer. Membrane proteins assemble into liposomes to form proteoliposomes

Sample preparation for cryo-EM: overview

Membrane proteins such as ion channels, transporters, pumps, and cell surface receptors play essential roles in regulating cell activity, such as transmembrane substance trafficking, sensing and signaling, gas exchange, and energy synthesis. These proteins have at least one, and frequently more than six, membrane-spanning helices with extracellular and intracellular domains. For structural analysis, the membrane proteins are usually extracted from the membrane using detergents. The isolated proteins are generally unstable and denature easily. At concentrations lower than the critical micelle concentration (CMC), detergent is dissolved as a monomer (or an ion) at which no micelles are detected in the solution. Above the CMC all additional detergent molecules form micelles and exhibit the properties of a colloidal solution. To minimize denaturation, solubilized proteins should be handled in aqueous solutions containing detergent at a concentration above the CMC.

After solubilization, the target proteins are subjected to purification procedures to improve their concentration and purity. They are enriched by a combination of different purification procedures, including affinity chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). SEC also reveals the condition of the protein, with additional peaks appearing if there is significant denaturation or aggregation. In the case of membrane proteins, the peaks obtained by SEC frequently become ambiguous due to the presence of the detergent in the buffer. Fluorescence-detection SEC (FSEC) is frequently used to identify the absorbance of proteins from various contaminants. In FSEC, the target protein is usually expressed as a fusion protein with a fluorescence tag, such as green fluorescent protein (Kawate and Gouaux 2006). The condition of the protein, especially the formation of the proper multimeric structure or the degree of aggregation, can be also monitored by negative staining transmission EM. The protein is adsorbed to the carbon film of an EM grid and surrounded by a high-scattering salt, which gives a negative contrast in the microscopy image (Bremer et al. 1992) (Fig. 1a, left). The atmospheric scanning EM (Nishiyama et al. 2010) in combination with metal staining is also useful in a direct observation of protein aggregation in buffer. It is recommended to carry out SEC immediately before the sample is adsorbed to the EM grid to ensure that it is homogeneous (Mio et al. 2007).

To prepare samples in vitrified ice, a solution containing target proteins is applied to an EM grid coated with a perforated carbon film (holey grid), and excess liquid is blotted away using a filter paper. At this stage, the residual protein suspension spans the large numbers of small holes in the perforated carbon film. To avoid diffraction from the ice crystal, the sample should be rapidly frozen using liquid ethane slush at liquid nitrogen temperature (Fig. 1a, right). The proteins embedded in vitrified ice (thickness of ice <500 nm) are in a close-to-native state (Adrian et al. 1984; Taylor and Glaeser 1976). As the density of the protein (~ 1.36 g/ml) is slightly higher than that of the vitrified ice, the particle images appear dark in a lighter background.

The vitrified ice functions as a “supporting film” for the target proteins, which require neither fixation nor staining. However, the contrast of particles in ice is very low and, in most cases, large-scale, image-alignment classification and averaging is required to obtain a clearer view of the particles. The cryo-embedded samples are transferred to the cryo-EM using a cryo-transfer instrument and observed at liquid nitrogen or liquid helium temperature.

Solubilization and stabilization of membrane proteins by detergents

In the native state, membrane proteins are embedded in the lipid bilayer with their hydrophobic transmembrane domains submerged at the fatty acid layer. Various detergents have been conventionally used to solubilize these proteins from the membrane and to allow their stable handling in the solution environment (Moraes et al. 2014; Privé 2007; Seddon et al. 2004). The standard detergents are divided into two groups, ionic and nonionic detergents. Ionic detergents have dissociative groups in their molecules, which may be cationic, anionic, or amphoteric. A representative anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) has a high ability to solubilize membrane. However, SDS is not suitable to purify membrane proteins because it strongly binds to proteins and causes severe protein deformation. On the other hand, nonionic detergents like Triton X-100, amphoteric detergents like CHAPS, anionic bile salt surfactants such as sodium cholate and sodium deoxycholate are known to be non-denaturing detergents.

Cholate-type ionic detergents contain a steroid skeleton, and hydrophilic groups are dispersed in the molecule. For example, cholate has a carboxyl group at its terminal, with three phenolic hydroxyl groups in the steroid skeleton. Deoxycholate, which has two hydroxyl groups, has weaker hydrophilicity than cholate and shows a stronger detergent action. The size of the deoxycholate micelle is small and it is easy to remove these micelles by dialysis.

Nonionic alkyl maltosides are most commonly used for the solubilization and purification of membrane proteins (Rosevear et al. 1980). The alkyl maltosides, such as n-Decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM) and n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), contain hydrophilic maltose and a hydrophobic alkyl chain. Desired variations in the alkyl chain modify the detergent properties, which also affects their CMC and their solubility. For example, the CMC of DM is 1.8 mM (Alpes et al. 1988) while that of DDM is 0.17 mM (VanAken et al. 1986).

As the preference of detergents for each membrane protein differs from one protein to another, the correct selection of the most suitable detergent for the target protein is vital. This approach should be based on an understanding of the physical and chemical properties of target membrane proteins. However, while in some cases researchers may find a preferred combination of membrane proteins and detergents, there is no unified rule, and in most cases we have to rely on empirical screening (Arachea et al. 2012; Privé 2007) (Fig. 3). In some cases, a detergent used for solubilization is substituted with different types of detergents during purification or a mixture of detergents may be used. It should be taken into account that the detergents remove proteins from their natural lipid environment, resulting in loss of all native interactions with lipids and with other membrane proteins. Furthermore, the detergent micelle is a spherical vesicle in which the hydrocarbon chain faces inward and the hydrophilic polar head group faces outward; as such it is topologically different from the lipid bilayer of cells and organelles (Bordag and Keller 2010; Zhou and Cross 2013).

Fig. 3.

Cryo-EM of the Burkholderia pseudomallei N-type ATPase rotor ring. a–d The two-dimensional class averages the B. pseudomallei c-ring complex, showing a clear correlation between the density of the detergent [n-dodecyl-N,N-dimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO) 0.88 g/ml; n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) 1.19 g/ml; C12E8 1.04 g/ml] or amphipol (1.3–1.9 g/ml) and the resolution achieved. e, f. Top and side views, respectively, of the rotor ring in LDAO with subunits fitted. Reproduced from Schulz et al. (2017) with permission

When the detergent forms micelles, it is in equilibrium between monomers and micelles. As both the CMC and the micelle size are intrinsic properties of the detergent, it is important to use this information in the rational selection of a detergent for a particular protein system. If inappropriate detergents are selected, the membrane proteins may show functional abnormality or physical aggregation. We observed that too high a concentration of solubilizing detergents can cause the dissociation of subunits from a certain kind of ion channels (Mio et al. 2010). In order to solve these problems, much effort has been taken to develop new detergents.

Using cryo-EM and strict optimization of the detergents, many high-resolution structures of membrane proteins have been successfully obtained. However, in general, detergents used to prevent the denaturation and aggregation of proteins diminish the contrast of proteins in cryo-EM images (Schmidt-Krey and Rubinstein 2011). The recently reported GraDeR method provides a way to remove free detergent micelles from the specimen using a glycerol density gradient and amphiphilic detergent, such as lauryl maltose-neopentyl glycol (Hauer et al. 2015). In the GraDeR methods, the concentration of detergent in the sample can be moderately lowered, which can contribute to an improved resolution in the cryo-EM structure determination (Oshima et al. 2016).

Various approaches have been taken to overcome the disadvantage of detergents. Detergents used to solubilize membrane proteins can be substituted with more stable polymers, such as amphipols. Detergent-solubilized membrane proteins can be reconstituted into lipid nanoparticles, such as liposomes and bicelles. In recent years, nanodisc technology has also frequently been used, such that membrane proteins and surrounding lipid bilayer are bundled with scaffold proteins or various types of polymers to generate small uniformly sized, disk-shaped particles (Fig. 2).

Amphipols

Since detergents lower the contrast of proteins in cryo-EM images, novel approaches have been proposed to replace the detergents surrounding the transmembrane helices, using specifically designed stable polymers (Althoff et al. 2011; Cvetkov et al. 2011). Amphipols are defined as “amphipathic polymers that are able to keep individual membrane proteins soluble in the form of small complexes” (Popot et al. 2011). Among the variously synthesized polymers, amphipol A8-35 has been most intensively studied and is now broadly used (Tribet et al. 1996). Amphipol A8-35 has a structure in which octylamine and isopropylamine are randomly arranged in an extensively hydrated polyacrylate skeleton (Tribet et al. 1996). The high solubility of amphipols is generated by the carboxylate group of the side chain. Amphipols have many hydrophobic side chains that bind to the hydrophobic surface of the membrane proteins. The multiple association between the amphipols and membrane proteins strengthens their binding and stabilizes the membrane proteins in native structure in the solution without the use of a detergent. The replacement of detergents with amphipols enables the cryo-EM specimen to exclude detergent micelles and monomers, and it restricts overall conformational flexibility. A capsaicin receptor, TRPV1, was the first protein to undergo high-resolution analysis using amphipol A8-35 (Liao et al. 2013). In that study, strongly bound lipid molecules were separately identified in the structures (Liao et al. 2013). Replacing digitonin with amphipol A8-35 was found to greatly improve the resolution of γ-secretase in cryo-EM studies (Bai et al. 2015; Lu et al. 2014). In subsequent studies, amphipols enabled high-resolution analysis of other intramembrane structures, such as polycystic kidney disease 2 (PKD2) (Wilkes et al. 2017) and V-type ATPase (Mazhab-Jafari et al. 2016).

Reconstituting membrane proteins into lipid bilayers

Membrane proteins extracted with detergents and/or treated with amphipols show high solubility and stability, but they still exist in an environment different from the actual lipid environment in which the membrane proteins normally function. Many studies have demonstrated that an interaction between membrane proteins and the surrounding lipid is critical for the protein’s function (Phillips et al. 2009; Saliba et al. 2015; Zhou and Cross 2013). Indeed, membrane structure and lipid composition modulate the structure, function, and stability of the membrane proteins. One of the approaches used to overcome this problem involves the reconstitution of purified proteins into an artificial lipid membrane. In this context, the reconstitution of membrane proteins into liposomes is the most commonly applied technique for the functional analysis of membrane proteins (Hinkle et al. 1972; Kagawa and Racker 1971). Liposomes were first described by Brangham and Home (1964). Using negative staining EM, these authors found spherulites composed of concentric lamellae in the lecithin dispersions. Subsequent liposome preparation techniques included vortexing, sonication, freeze-thaw, and detergent removal. For example, the detergent reconstitution strategy for proteoliposome proceeds in four stages: (1) preparation of large, homogeneous, and unilamellar liposomes; (2) addition of detergent to the preformed liposomes, through all the range of the solubilization process; (3) addition of solubilized protein at each well-defined step of the solubilization process; (4) detergent removal and characterization of the reconstituted products (Rigaud and Lévy 2003). Membrane proteins incorporated into liposomes are considered to be in a near-native state, and structures of transmembrane helices most likely reflect those in the original cell or organelles membranes.

Although analysis is not necessarily easy due to the different diameters and curvatures of the proteoliposomes, Wang and Sigworth succeeded in describing the structure of the voltage-activated BK potassium channel embedded in liposomes by subtracting the electron density of lipid vesicles from that of proteoliposomes (Wang and Sigworth 2009). More recently, an improved structure of the BK channel (Jensen et al. 2016) and a structure of serotonin 5-HT3 receptor in small lipid vesicles have been reported (Kudryashev et al. 2016). The liposome was further used for gaining an understanding of the mechanisms of bacteriophage tails involved in the penetration of the inner host cell membrane (Xu et al. 2016).

Proteoliposomes can be further integrated into black membranes. This is an immobilized “in vitro bilayer” system and can be used for the functional analysis of channels and transporters (Montal and Mueller 1972; Murray et al. 2009). Integration of the proteoliposome into the supported bilayer is a frequently used method for imaging membrane proteins using atomic force microscopy (Richter et al. 2003).

By strictly controlling the phospholipid and detergent ratio, disc-shaped particles with diameters of several hundred angstroms and thicknesses of ~ 40 Å, referred to as bicelles, can be generated. Because protein molecules are gently aligned in bicelles, and it is possible to determine how each bond between neighboring atoms is oriented with respect to the rest of the molecule, bicelles are a useful tool for analyzing membrane proteins in the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Dürr et al. 2012; Tjandra and Bax 1997; Warschawski et al. 2011).

Membrane protein assembly into nanodiscs

The function of membrane proteins often depends on direct interaction with lipids (Phillips et al. 2009; Saliba et al. 2015; Zhou and Cross 2013). In recent years, the most commonly used lipid bilayer environment is the nanodisc technology (Denisov and Sligar 2016, 2017). The nanodisc uses a membrane scaffold protein (MSP) (Bayburt et al. 2002) with various lengths and characteristics. Nanodiscs are originally constructed on the basis of the structure of apolipoprotein A-1 (Apo-A1) (Brouillette et al. 1984). Two MSPs form either a parallel or antiparallel belt around the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayer incorporating the membrane protein inside. MSPs have amphipathic helixes and surround the lipid in a disc shape to build a stable particle in aqueous solution. Various MSPs have been developed, mainly in Stephen Sligar’s laboratory at the University of Illinois (Bayburt et al. 2002; Bayburt and Sligar 2003), such that nanodiscs with a diameter from 6 to 17 nm are able to be constructed (Grinkova et al. 2010; Hagn et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2015). The number of lipids incorporated into one nanodisc depends on the selected MSP and lipid combination. The MSP1D1, which typically generates a disk size of 9.6 nm, incorporates 65 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholines (POPC) or 90 1, 2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholines (DPPC), while MSP1E1D1 has a diameter of 10.5 nm and incorporates 85 POPCs or 115 DPPCs per nanodisc (Ritchie et al. 2009).

Nanodisc technology, yielding relatively high protein stability, has been widely applied to functional and structural analysis of membrane proteins (Denisov and Sligar 2017). Introduction of an affinity tag into the MSP by genetic engineering is useful for the purification and functional analysis of generated nanodiscs. By combining this with another tag system introduced into the target membrane proteins, one can easily concentrate the target nanodiscs containing the desired membrane proteins from the large amount of empty nanodiscs.

As with other double-layer systems, it is possible to select and tune the lipid components of nanodiscs, which makes it possible to analyze the interaction between the membrane proteins and surrounding lipids. Nanodiscs can be also used to analyze oligomer state or interaction with other membrane proteins (Boldog et al. 2006; Shih et al. 2005). Nanodiscs can be handled like soluble molecules and are effectively used for both solution NMR (Hagn and Wagner 2015; Zhang et al. 2016) and solid state NMR (Li et al. 2006; Opella and Marassi 2017) in addition to EM studies.

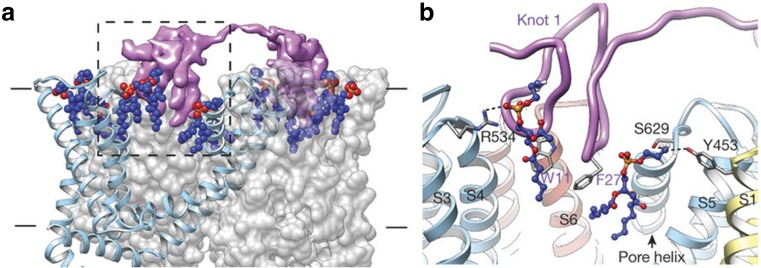

Indeed, cryo-EM may be the technique where the advantages of nanodiscs are most effectively utilized for structural analysis. Membrane proteins reconstituted into nanodiscs have a stable intramembrane structure, and detergents are removed during purification. The nanodisc can be analyzed as a soluble “single particle”. Many structures of membrane proteins have been solved in the lipid bilayer by cryo-EM using nanodisc systems, including bacterial ribosomes–SecYE complex (Frauenfeld et al. 2011), ribosome–YidC complex (Kedrov et al. 2016), the muscle isoform of the ryanodine receptor (RyR1) (Efremov et al. 2015), a more recently high-resolution study of Tc toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens (Gatsogiannis et al. 2016), and the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) (Gao et al. 2016) and polycystin-2 (PKD2) (Shen et al. 2016). Particularly in the case of TRPV1, the resolution of TRPV1 in complex with double-knot toxin (DkTx) and resiniferatoxin (RTX) was 2.9 Å in nanodisc-embedded form (Gao et al. 2016), which represented a drastic improvement from the 3.8-Å resolution obtained from the amphipol-substituted specimen (Liao et al. 2013). Evident improvement of the quality was observed in side-chain densities within transmembrane regions or connecting loops that face lipids, and further improvement was observed even in the cytoplasmic domains (Gao et al. 2016). In the structure, interactions among tightly bound lipids, amino acid side chains from the TRPV1 and from the DkTx were clearly demonstrated (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Structure of tripartite double-knot toxin (DkTx)– transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1)–lipid complex reconstituted in a nanodisc. In the reconstructed three-dimensional structure (a, left) and its enlarged view (b, right), interactions among tightly bound lipids, amino acid side chains from the TRPV1 and from the DkTx are clearly demonstrated. One DkTx molecule (top, colored purple) interacting with two adjacent TRPV1 subunits (gray) and associated lipids (blue spheres with red and orange colored phosphate head groups). The 2.9-Å resolution of the TRPV1 complex in this study (nanodisc embedded form) was much improved from the 3.8-Å resolution obtained from the amphipol-substituted specimen (Liao et al. 2013). Reproduced from Gao et al. (2016) with permission

Members of the saposin protein family have membrane-binding and lipid-transport properties and also can be used to generate lipid–protein nanoparticles. Using the saposin–lipoprotein (Salipro) nanoparticle system, the structure of bacterial peptide transporter PeptTSo2 was reconstructed by SPA with cryo-EM at a resolution of 6.5 Å (Frauenfeld et al. 2016).

Discoidal particles using styrene-maleic acid copolymer

Recently, a styrene–maleic acid copolymer (SMA) was developed which directly solubilizes biological membranes and automatically generates discoidal particles with a diameter of about 10 nm (Tonge and Tighe 2001). Several research groups have reported usage of this type of nanodisc, referred to as SMA–lipid particles (SMALP) (Knowles et al. 2009), Lipodisq particles (Orwick et al. 2012), or native Nanodiscs (Dörr et al. 2014). SMA is a copolymer of styrene and maleic acid/anhydride. In this technique, the styrene maleic anhydride polymer is first generated by radical polymerization of maleic anhydride and styrene. In the second step, a hydration reaction of the styrene maleic anhydride generates the SMA copolymer. A styrene-to-maleic acid ratio of 2:1 to 3:1 is commonly used to construct SMA-based nanodiscs. In this new type of polymer-bound nanodiscs, the bilayer structure of the incorporated lipid molecule is conserved (Jamshad et al. 2015; Orwick et al. 2012).

A unique feature of the SMA copolymer is that without requiring detergent, it can solubilize the cell membrane spontaneously. Therefore, starting materials are not limited to the purified proteins, but can be the fractionized membrane from the cell lysate or intact cells whether they are mammalian cells or of microorganisms.

Since it is possible to conduct direct extraction of membrane proteins from cells without the use of detergents (Long et al. 2013), the obtained nanodiscs preserve the original lipid environment. Until now, there are only a few applications of SMA co-polymer for the structural analysis of membrane proteins, but it has been used in various biochemical and biophysical analysis (Dörr et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2016).

Concluding remarks

The progress of cryo-EM in recent years has been remarkable, and the reported structures feature atomic resolution or near-atomic resolution even for small proteins in the vicinity of 100 kDa. For soluble proteins, a structure of the 93-kDa isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) was analyzed at 3.8-Å resolution (Merk et al. 2016) and the 64-kDa protein hemoglobin was analyzed at 3.2-Å resolution by contrast-enhanced cryo-EM using a Volta phase plate (Khoshouei et al. 2017). The structure of the 464-kDa protein β-galactosidase was obtained at 2.2-Å resolution as D2 symmetry (Bartesaghi et al. 2015). The structural analysis of membrane proteins is increasingly becoming an interesting and challenging area of research. Cryo-EM is undoubtedly becoming a powerful technique of choice. For example, at least six structures of cellular sensor TRP isoforms, namely, TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPA1, PKD2, transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1), and no mechanoreceptor potential C (NOMPC), have been determined by cryo-EM at near-atomic resolution (Jin et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Liao et al. 2013; Paulsen et al. 2015; Wilkes et al. 2017; Zubcevic et al. 2016). The development of novel strategies for sample preparation will undoubtedly contribute to further improvements in resolution in cryo-EM-based 3-D structure determination.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Kazuhiro Mio declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Chikara Sato declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘Biomolecules to Bio-nanomachines—Fumio Arisaka 70th Birthday’ edited by Damien Hall, Junichi Takagi and Haruki Nakamura

Contributor Information

Kazuhiro Mio, Email: kazu.mio@aist.go.jp.

Chikara Sato, Email: ti-sato@aist.go.jp.

References

- Adrian M, Dubochet J, Lepault J, McDowall AW. Cryo-electron microscopy of viruses. Nature. 1984;308:32–36. doi: 10.1038/308032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpes H, Apell H-J, Knoll G, Plattner H, Riek R. Reconstitution of Na+/K+-ATPase into phosphatidylcholine vesicles by dialysis of nonionic alkyl maltoside detergents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;946:379–388. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff T, Mills DJ, Popot JL, Kühlbrandt W. Arrangement of electron transport chain components in bovine mitochondrial supercomplex I 1 III 2 IV 1. EMBO J. 2011;30:4652–4664. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arachea BT, Sun Z, Potente N, Malik R, Isailovic D, Viola RE. Detergent selection for enhanced extraction of membrane proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2012;86:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X-c, Yan C, Yang G, Lu P, Ma D, Sun L, Zhou R, Scheres SH, Shi Y. An atomic structure of human γ-secretase. Nature. 2015;525:212. doi: 10.1038/nature14892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MR, Fan G, Serysheva II. Structure of IP3R channel: high-resolution insights from cryo-EM. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;46:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangham AD, Horne R. Negative staining of phospholipids and their structural modification by surface-active agents as observed in the electron microscope. J Mol Biol. 1964;8:660–668. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi A, Merk A, Banerjee S, Matthies D, Wu X, Milne JL, Subramaniam S. 2.2 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of β-galactosidase in complex with a cell-permeant inhibitor. Science. 2015;348:1147–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Self-assembly of discoidal phospholipid bilayer nanoparticles with membrane scaffold proteins. Nano Lett. 2002;2:853–856. [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. Self-assembly of single integral membrane proteins into soluble nanoscale phospholipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2476–2481. doi: 10.1110/ps.03267503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldog T, Grimme S, Li M, Sligar SG, Hazelbauer GL. Nanodiscs separate chemoreceptor oligomeric states and reveal their signaling properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11509–11514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604988103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordag N, Keller S. α-helical transmembrane peptides: a “divide and conquer” approach to membrane proteins. Chem Phys Lipids. 2010;163:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer A, Henn C, Engel A, Baumeister W, Aebi U. Has negative staining still a place in biomacromolecular electron microscopy? Ultramicroscopy. 1992;46:85–111. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(92)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette CG, Jones JL, Ng TC, Kercret H, Chung BH, Segrest JP. Structural studies of apolipoprotein AI/phosphatidylcholine recombinants by high-field proton NMR, nondenaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, and electron microscopy. Biochemistry. 1984;23:359–367. doi: 10.1021/bi00297a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkov TL, Huynh KW, Cohen MR, Moiseenkova-Bell VY. Molecular architecture and subunit organization of TRPA1 ion channel revealed by electron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38168–38176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.288993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs for structural and functional studies of membrane proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:481–487. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Nanodiscs in membrane biochemistry and biophysics. Chem Rev. 2017;117:4669–4713. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörr JM, Koorengevel MC, Schäfer M, Prokofyev AV, Scheidelaar S, van der Cruijsen EA, Dafforn TR, Baldus M, Killian JA. Detergent-free isolation, characterization, and functional reconstitution of a tetrameric K+ channel: the power of native nanodiscs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:18607–18612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416205112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörr JM, Scheidelaar S, Koorengevel MC, Dominguez JJ, Schäfer M, van Walree CA, Killian JA. The styrene–maleic acid copolymer: a versatile tool in membrane research. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45:3–21. doi: 10.1007/s00249-015-1093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews J. Drug discovery: a historical perspective. Science. 2000;287:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürr UH, Gildenberg M, Ramamoorthy A. The magic of bicelles lights up membrane protein structure. Chem Rev. 2012;112:6054–6074. doi: 10.1021/cr300061w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov RG, Leitner A, Aebersold R, Raunser S. Architecture and conformational switch mechanism of the ryanodine receptor. Nature. 2015;517:39. doi: 10.1038/nature13916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AW, Llabrés S, Neuberger A, Blaza JN, Bai X-C, Okada U, Murakami S, van Veen HW, Zachariae U, Scheres SH. Structure of the MacAB-TolC ABC-type tripartite multidrug efflux pump. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17070. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenfeld J, Gumbart J, Van Der Sluis EO, Funes S, Gartmann M, Beatrix B, Mielke T, Berninghausen O, Becker T, Schulten K. Cryo-EM structure of the ribosome–SecYE complex in the membrane environment. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:614–621. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenfeld J, Löving R, Armache JP, Sonnen AF, Guettou F, Moberg P, Zhu L, Jegerschöld C, Flayhan A, Briggs JA, Garoff H, Löw C, Cheng Y, Nordlund P. A saposin-lipoprotein nanoparticle system for membrane proteins. Nat Methods. 2016;13:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature. 2016;534:347. doi: 10.1038/nature17964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatsogiannis C, Merino F, Prumbaum D, Roderer D, Leidreiter F, Meusch D, Raunser S. Membrane insertion of a Tc toxin in near-atomic detail. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinkova YV, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Engineering extended membrane scaffold proteins for self-assembly of soluble nanoscale lipid bilayers. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2010;23:843–848. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Zeng W, Chen Q, Lee C, Chen L, Yang Y, Cang C, Ren D, Jiang Y (2016) Structure of voltage-gated two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 531:196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hagn F, Etzkorn M, Raschle T, Wagner G. Optimized phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs facilitate high-resolution structure determination of membrane proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1919–1925. doi: 10.1021/ja310901f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagn F, Wagner G. Structure refinement and membrane positioning of selectively labeled OmpX in phospholipid nanodiscs. J Biomol NMR. 2015;61:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9883-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer F, Gerle C, Fischer N, Oshima A, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Shimada S, Yokoyama K, Fujiyoshi Y, Stark H. GraDeR: membrane protein complex preparation for single-particle cryo-EM. Structure. 2015;23:1769–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle PC, Kim JJ, Racker E. Ion transport and respiratory control in vesicles formed from cytochrome oxidase and phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:1338–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshad M, Grimard V, Idini I, Knowles TJ, Dowle MR, Schofield N, Sridhar P, Lin Y, Finka R, Wheatley M. Structural analysis of a nanoparticle containing a lipid bilayer used for detergent-free extraction of membrane proteins. Nano Res. 2015;8:774–789. doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KH, Brandt SS, Shigematsu H, Sigworth FJ. Statistical modeling and removal of lipid membrane projections for cryo-EM structure determination of reconstituted membrane proteins. J Struct Biol. 2016;194:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Bulkley D, Guo Y, Zhang W, Guo Z, Huynh W, Wu S, Meltzer S, Cheng T, Jan LY. Electron cryo-microscopy structure of the mechanotransduction channel NOMPC. Nature. 2017;547:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature22981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ZL, Chen J. Structural basis of substrate recognition by the multidrug resistance protein MRP1. Cell. 2017;168:1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa Y, Racker E (1971) Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation XXV. Reconstitution of vesicles catalyzing 32Pi—adenosine triphosphate exchange. J Biol Chem 246:5477–5487

- Kawate T, Gouaux E. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography for precrystallization screening of integral membrane proteins. Structure. 2006;14:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedrov A, Wickles S, Crevenna AH, van der Sluis EO, Buschauer R, Berninghausen O, Lamb DC, Beckmann R. Structural dynamics of the YidC: ribosome complex during membrane protein biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2943–2954. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshouei M, Radjainia M, Baumeister W, Danev R. Cryo-EM structure of haemoglobin at 3.2 Å determined with the Volta phase plate. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16099. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wu S, Tomasiak TM, Mergel C, Winter MB, Stiller SB, Robles-Colmanares Y, Stroud RM, Tampé R, Craik CS. Subnanometre-resolution electron cryomicroscopy structure of a heterodimeric ABC exporter. Nature. 2015;517:396–400. doi: 10.1038/nature13872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. elife. 2016;5:e18722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles TJ, Finka R, Smith C, Lin Y-P, Dafforn T, Overduin M. Membrane proteins solubilized intact in lipid containing nanoparticles bounded by styrene maleic acid copolymer. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7484–7485. doi: 10.1021/ja810046q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryashev M, Castaño-Díez D, Deluz C, Hassaine G, Grasso L, Graf-Meyer A, Vogel H, Stahlberg H. The structure of the mouse serotonin 5-HT3 receptor in lipid vesicles. Structure. 2016;24:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Knowles TJ, Postis VL, Jamshad M, Parslow RA, Lin Y-p, Goldman A, Sridhar P, Overduin M, Muench SP. A method for detergent-free isolation of membrane proteins in their local lipid environment. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1149–1162. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kijac AZ, Sligar SG, Rienstra CM. Structural analysis of nanoscale self-assembled discoidal lipid bilayers by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2006;91:3819–3828. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhang WK, Benvin NM, Zhou X, Su D, Li H, Wang S, Michailidis IE, Tong L, Li X. Structural basis of Ca2+/pH dual regulation of the endolysosomal TRPML1 channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:205. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y-L, Khoshouei M, Radjainia M, Zhang Y, Glukhova A, Tarrasch J, Thal DM, Furness SG, Christopoulos G, Coudrat T. Phase-plate cryo-EM structure of a class B GPCR–G-protein complex. Nature. 2017;546:118–123. doi: 10.1038/nature22327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:107. doi: 10.1038/nature12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Zhang Z, Csanády L, Gadsby DC, Chen J. Molecular structure of the human CFTR ion channel. Cell. 2017;169:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long AR, O’Brien CC, Malhotra K, Schwall CT, Albert AD, Watts A, Alder NN. A detergent-free strategy for the reconstitution of active enzyme complexes from native biological membranes into nanoscale discs. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Bai X-c, Ma D, Xie T, Yan C, Sun L, Yang G, Zhao Y, Zhou R, Scheres SH. Three-dimensional structure of human γ-secretase. Nature. 2014;512:166. doi: 10.1038/nature13567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhab-Jafari MT, Rohou A, Schmidt C, Bueler SA, Benlekbir S, Robinson CV, Rubinstein JL. Atomic model for the membrane-embedded VO motor of a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature. 2016;539:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature19828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhab-Jafari MT, Rubinstein JL. Cryo-EM studies of the structure and dynamics of vacuolar-type ATPases. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600725. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan G, Faruqi A, Clare D, Henderson R. Comparison of optimal performance at 300keV of three direct electron detectors for use in low dose electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2014;147:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merk A, Bartesaghi A, Banerjee S, Falconieri V, Rao P, Davis MI, Pragani R, Boxer MB, Earl LA, Milne JL. Breaking cryo-EM resolution barriers to facilitate drug discovery. Cell. 2016;165:1698–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic D, Blaza JN, Larsson N-G, Hirst J. The enigma of the respiratory chain Supercomplex. Cell Metab. 2017;25:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Mio M, Arisaka F, Sato M, Sato C. The C-terminal coiled-coil of the bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel NaChBac is not essential for tetramer formation, but stabilizes subunit-to-subunit interactions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2010;103:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Ogura T, Kiyonaka S, Hiroaki Y, Tanimura Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Mori Y, Sato C. The TRPC3 channel has a large internal chamber surrounded by signal sensing antennas. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montal M, Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes I, Evans G, Sanchez-Weatherby J, Newstead S, Stewart PDS. Membrane protein structure determination—the next generation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DH, Tamm LK, Kiessling V. Supported double membranes. J Struct Biol. 2009;168:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama H, Suga M, Ogura T, Maruyama Y, Koizumi M, Mio K, Kitamura S, Sato C. Atmospheric scanning electron microscope observes cells and tissues in open medium through silicon nitride film. J Struct Biol. 2010;169:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham ML, Hite RK, Steffen AM, Damko E, Li Z, Walz T, Chen J. A mechanism of viral immune evasion revealed by cryo-EM analysis of the TAP transporter. Nature. 2016;529:537. doi: 10.1038/nature16506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opella SJ, Marassi FM. Applications of NMR to membrane proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;628:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwick MC, Judge PJ, Procek J, Lindholm L, Graziadei A, Engel A, Gröbner G, Watts A. Detergent-free formation and physicochemical characterization of nanosized lipid–polymer complexes: Lipodisq. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:4653–4657. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A, Tani K, Fujiyoshi Y. Atomic structure of the innexin-6 gap junction channel determined by cryo-EM. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13681. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen CE, Armache J-P, Gao Y, Cheng Y, Julius D. Structure of the TRPA1 ion channel suggests regulatory mechanisms. Nature. 2015;520:511. doi: 10.1038/nature14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R, Ursell T, Wiggins P, Sens P. Emerging roles for lipids in shaping membrane-protein function. Nature. 2009;459:379. doi: 10.1038/nature08147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot J-L, Althoff T, Bagnard D, Banères J-L, Bazzacco P, Billon-Denis E, Catoire LJ, Champeil P, Charvolin D, Cocco M. Amphipols from A to Z. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privé GG. Detergents for the stabilization and crystallization of membrane proteins. Methods. 2007;41:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Zhao X, Cao P, Lei J, Yan N, Gong X. Structure of the human lipid exporter ABCA1. Cell. 2017;7:1228–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter R, Mukhopadhyay A, Brisson A. Pathways of lipid vesicle deposition on solid surfaces: a combined QCM-D and AFM study. Biophys J. 2003;85:3035–3047. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74722-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud J-L, Lévy D. Reconstitution of membrane proteins into liposomes. Methods Enzymol. 2003;372:65–86. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)72004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie T, Grinkova Y, Bayburt T, Denisov I, Zolnerciks J, Atkins W, Sligar S. Chapter eleven-reconstitution of membrane proteins in phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs. Methods Enzymol. 2009;464:211–231. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosevear P, VanAken T, Baxter J, Ferguson-Miller S. Alkyl glycoside detergents: a simpler synthesis and their effects on kinetic and physical properties of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4108–4115. doi: 10.1021/bi00558a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba A-E, Vonkova I, Gavin A-C. The systematic analysis of protein-lipid interactions comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:753. doi: 10.1038/nrm4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Krey I, Rubinstein JL. Electron cryomicroscopy of membrane proteins: specimen preparation for two-dimensional crystals and single particles. Micron. 2011;42:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Wilkes M, Mills DJ, Kühlbrandt W, Meier T. Molecular architecture of the N-type ATPase rotor ring from Burkholderia pseudomallei. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:526–535. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon AM, Curnow P, Booth PJ. Membrane proteins, lipids and detergents: not just a soap opera. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen PS, Yang X, DeCaen PG, Liu X, Bulkley D, Clapham DE, Cao E. The structure of the polycystic kidney disease channel PKD2 in lipid nanodiscs. Cell. 2016;167:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Zhou Q, Pan X, Li Z, Wu J, Yan N. Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science. 2017;355:eaal4326. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih AY, Denisov IG, Phillips JC, Sligar SG, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics simulations of discoidal bilayers assembled from truncated human lipoproteins. Biophys J. 2005;88:548–556. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KA, Glaeser RM. Electron microscopy of frozen hydrated biological specimens. J Ultrastruct Res. 1976;55:448–456. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(76)80099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NM, Manolaridis I, Jackson SM, Kowal J, Stahlberg H, Locher KP. Structure of the human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature. 2017;546:504–509. doi: 10.1038/nature22345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terstappen GC, Reggiani A. In silico research in drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra N, Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonge S, Tighe B. Responsive hydrophobically associating polymers: a review of structure and properties. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:109–122. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot J-L. Amphipols: polymers that keep membrane proteins soluble in aqueous solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15047–15050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanAken T, Foxall-VanAken S, Castleman S, Ferguson-Miller S. Alkyl glycoside detergents: synthesis and applications to the study of membrane proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1986;125:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)25005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin E, Heijne GV. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Sigworth FJ. Cryo-EM structure of the BK potassium channel in a lipid membrane. Nature. 2009;461:292. doi: 10.1038/nature08291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mu Z, Li Y, Bi Y, Wang Y. Smaller nanodiscs are suitable for studying protein lipid interactions by solution NMR. Protein J. 2015;34:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s10930-015-9613-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warschawski DE, Arnold AA, Beaugrand M, Gravel A, Chartrand É, Marcotte I. Choosing membrane mimetics for NMR structural studies of transmembrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:1957–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whicher JR, MacKinnon R. Structure of the voltage-gated K+ channel Eag1 reveals an alternative voltage sensing mechanism. Science. 2016;353:664–669. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes M, Madej MG, Kreuter L, Rhinow D, Heinz V, De Sanctis S, Ruppel S, Richter RM, Joos F, Grieben M. Molecular insights into lipid-assisted Ca2+ regulation of the TRP channel Polycystin-2. Nature. 2017;201:123–130. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Yan Z, Li Z, Qian X, Lu S, Dong M, Zhou Q, Yan N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1. 1 at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2016;537:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature19321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Gui M, Wang D, Xiang Y. The bacteriophage phi29 tail possesses a pore-forming loop for cell membrane penetration. Nature. 2016;534:544–544. doi: 10.1038/nature18017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Zhou R, Shi Y. Cryo-EM structures of human γ-secretase. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;46:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalk R, Marks AR. Ca2+ release channels join the ‘resolution revolution. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:543–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Huang R, Ackermann R, Im SC, Waskell L, Schwendeman A, Ramamoorthy A. Reconstitution of the Cytb5–CytP450 complex in nanodiscs for structural studies using NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:4497–4499. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sun B, Feng D, Hu H, Chu M, Qu Q, Tarrasch JT, Li S, Kobilka TS, Kobilka BK. Cryo-EM structure of the activated GLP-1 receptor in complex with a G protein. Nature. 2017;546:248–253. doi: 10.1038/nature22394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen J. Atomic structure of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Cell. 2016;167:1586–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H-X, Cross TA. Influences of membrane mimetic environments on membrane protein structures. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:361–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Gouaux E. Structure and symmetry inform gating principles of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2017;112:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubcevic L, Herzik Jr MA, Chung BC, Liu Z, Lander GC, Lee S-Y. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the TRPV2 ion channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:180. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]