Abstract

Although lay beliefs commonly relate high blood pressure to psychological stress exposure, research findings are conflicting. This study examined the association between current perceived stress and high blood pressure and explored the potential impact of occupational status on this association. Resting blood pressure was measured in 122,816 adults (84,994 men), aged ≥30 years (mean age ± standard deviation: 46.8±9.9 years), without history of cardiovascular and renal disease and not on either psychotropic or antihypertensive drugs. High blood pressure was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Perceived stress in the past month was measured with the 4-item perceived stress scale. A total of 33,154 participants (27.0%) had high blood pressure (151±14/90±9 mmHg). After adjustment for all variables except occupational status, perceived stress was associated with high blood pressure (odds ratio for a 5-point increase: 1.06, 95% confidence interval: [1.03–1.09]). This association was no longer significant after additional adjustment for occupational status (odds ratio: 1.01 [0.99–1.04]). There was a significant interaction (p<0.001) between perceived stress and occupational status in relation to blood pressure: perceived stress was negatively associated with high blood pressure among individuals of high occupational status (odds ratio: 0.91, [0.87–0.96]) but positively associated among those of low status (odds ratio: 1.10, [1.03–1.17]) or unemployed (odds ratio: 1.13, [1.03–1.24]). Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results. The association between current perceived stress and blood pressure depends upon occupational status. This interaction may account for previous conflicting results and warrants further studies to explore its underlying mechanisms.

Introduction

Hypertension is a leading risk factor for cardiovascular mortality worldwide and has several known risk factors such as obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol or salt intake 1. However, most patients with hypertension lend great importance to psychological stress in the regulation of blood pressure (BP) and in the need for taking antihypertensive drugs 2. Although acute psychological stress is associated with a transient BP elevation 3, epidemiological studies do not consistently show chronic psychological stress to affect BP in the long-term 4. Some studies found positive associations between psychological stress and hypertension 5,6, while others showed no 7,8 or even negative associations 9,10.

Reasons for these conflicting results can be potentially attributed to differences in the evaluation of psychological stress (e.g. objective measures versus subjective measures) or outcomes (e.g. BP threshold values, use of antihypertensive drugs). As regards psychological stress, objective measures quantify the exposure to several kinds of stressors (e.g. stressful life events, occupational stress) whereas subjective measures, such as perceived stress, quantify the psychological impact of these stressors 11. Previous studies may also have overlooked the potential confounding role of some psychosocial variables. For instance, few studies have included a measure of depression, which is linked to stress but may be associated with a lower BP 12,13. Another important factor is socioeconomic status (SES), which is negatively associated with hypertension, especially in high-income countries 14,15. However, studies adjusting for SES do not usually test for a moderation hypothesis (i.e. that stress may relate to hypertension to a different extent according to SES). Although there is preliminary evidence that job strain may relate to BP at work site to a different extent across certain occupational categories 16, little is known about the role of the SES in moderating the association of hypertension with perceived stress from a broader perspective, as well as among non-working individuals.

The aim of this study was to examine the association between perceived stress and BP, and to explore the potential moderating role of occupational status on this association. Occupational status is a useful proxy for SES as it integrates the educational achievements, the skills required to obtain a job, the long-term associated rewards (including, but not limited to, income) and several job characteristics, such as working conditions and decision-making latitude.

Methods

Participants

All participants were recruited at the “Investigations Préventives et Cliniques” (IPC) Center (Paris, France). This medical Center, which is subsidized by the French national health care system, offers all working and retired individuals and their families a free medical examination every five years. It carries out approximately 25,000 examinations per year for people living in the Paris area. Our target population was composed of all subjects who had at least one health checkup at the IPC Center in the period from January 1996 to December 2007. All clinical and biological parameters were evaluated on the same day at the examination. In the case of participants who benefited from more than one examination, only data from the first examination were considered. Eligibility criteria were: 30 years of age or more (owing to the low prevalence of hypertension in younger individuals), able to fill out the study questionnaires, and with no missing data for selected variables (see below). To minimize potential biases, individuals with a history of cardiovascular or renal disease and those who reported using antihypertensive or psychotropic drugs were not included in the first set of analyses but were included in sensitivity analyses. The IPC Center received authorization from a local ethics committee and from the “Comité National d’Informatique et des Libertés” to conduct these analyses. All subjects gave their informed consent at the time of the first examination. The procedures followed were in accordance with institutional guidelines. The data were rendered anonymous before analysis.

Blood pressure and outcome

After a 10-minute rest period, supine brachial systolic and diastolic BP were measured 3 times by trained nurses in the right arm using a semi-automated mercury sphygmomanometer. A standard cuff size was used, but a large cuff was utilized if necessary. The mean of the last 2 measurements was considered as the BP value. The primary outcome of the present study was a high BP, defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg 1.

Psychological variables

Perceived stress was measured with the French version of the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) 11,17. Each item is rated on a 0 to 4 scale (please see Appendix 1 in the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org). The PSS-4 total score has a one-factor structure and a satisfactory internal consistency (α=0.73). It measures the degree to which situations in one’s life over the past month were appraised as stressful (e.g. “In the past month, how often have you felt it was difficult to control the important things in your life?”). In order to obtain meaningful odds ratios, the variable was rescaled using the difference between the 25th and the 75th percentile as the unit.

Depressive mood was measured with a French 13-item questionnaire (QD2A, Questionnaire of Depression 2nd version, Abridged) 18,19. Building on previous questionnaires, this 13-item questionnaire was specifically designed for depression screening in community studies and has a high internal consistency (α=0.91). Participants had to give a yes/no answer to each item as regards their current emotional state (e.g. “I am disappointed and disgusted with myself,” “I’m sad these days,” “I feel hopeless about the future”). The number of “yes” answers is summed, a total score ≥ 7 indicating a high probability of major depression. The QD2A has been found to predict suicide in the IPC Cohort Study 20.

Occupational status

Occupational status was categorized in 6 classes: (1) high (e.g. managers); (2) medium (e.g. clerks or first line supervisors); (3) low (e.g. blue collar workers); (4) unemployed participants (i.e. seeking employment); (5) participants without a paid occupation (e.g. housewives); (6) others (e.g. artisans). Retired participants were assigned to their last occupational category. The distinction of three categories among working participants is standard among occupational cohorts examining the relationships between psychosocial variables and physical health outcomes 21.

Other covariates

Others covariates included age, gender, living status (living alone or not), smoking status (non-smoker, ex-smoker, current smoker of 1–10 cigarettes/day, 11–20 cigarettes/day, >20 cigarettes/day), at-risk alcohol intake (more than 2 glasses/day for women or 3 glasses/day for men), and regular physical activity (i.e. estimated equivalent to at least one hour/day of walking). Personal history of cardiovascular or renal disease, and family history of hypertension were self-reported (yes, no), as well as current medications including diuretics, antihypertensive drugs (other than diuretics), medications “to sleep” or “for anxiety or depression.” Among participants reporting taking diuretics, only those that reported doing this “to lower BP” were considered as taking an antihypertensive drug. Perceived health status was collected with a 10-point scale (with 10 considered to be “excellent health”). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and categorized in 4 classes (<18.5; 18.5–24.99; 25–29.99; ≥30 kg/m2). Resting heart rate (HR) was measured in beats per minute with a 10-cycle electrocardiogram (HR = 60/RR interval in seconds) and fasting glycemia in mmol/L.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with the PASW Statistics software (version 18.0). Except for BP, all variables were analyzed as continuous when available as such. Participants who had high BP and those who did not were first compared with respect to each variable with binary logistic regressions. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were then computed in three multivariate models. Model 1 included all variables except the occupational status which was added in model 2. Model 3 further included the interaction between stress and occupational status. A stratified analysis was conducted whenever the interaction was significant. Sensitivity analyses were also carried out, including participants who reported using antihypertensive drugs (considered as having high BP) or those with a history of cardiovascular or renal disease.

Results

Study population selection is described in Figure S1 (available in the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org). The final study population consisted of 122,816 participants (84,994 men and 37,822 women) with a mean age of 46.8±9.9 years. The mean perceived stress score was 3.7±2.9 with a 5-point difference between the 25th and the 75th percentile. Mean perceived stress scores among participants with high, medium and low occupational status were 2.9±3.9, 3.9±2.9 and 4.4±3.0, respectively (p for linear trend <0.001). Mean perceived stress scores among other categories were 4.9±3.2 in unemployed participants, 4.2±3.0 in participants with unpaid occupation and 3.7±2.8 in other participants.

A total of 33,154 participants (27.0%) had high BP (mean systolic/diastolic BP: 151±14/90±9 mmHg). Table S1 (available in the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org) shows the characteristics of study participants. Multivariate models are displayed in Table 1. The association between perceived stress and high BP was significant after adjustment for all variables except occupational status (i.e. model 1), but this association was no longer significant after further adjustment for occupational status (i.e. model 2).

Table 1.

Associations between high BP (systolic BP ≥140 or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg) and each variable in multivariate models.

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONTINUOUS VARIABLES * | OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] |

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 1.06† [1.06–1.06] | 1.06† [1.06–1.06] | 1.06† [1.06–1.06] |

| Perceived Stress (PSS-4) | 1.06† [1.03–1.09] | 1.01 [0.99–1.04] | 0.93‡ [0.89–0.98] |

| Depressive mood (QD2A) | 0.97† [0.96–0.98] | 0.98† [0.97–0.98] | 0.98† [0.97–0.98] |

| Perceived health status (10-point scale) | 0.98† [0.97–0.99] | 0.99 [0.98–1.00] | 0.99 [0.98–1.00] |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 1.05† [1.05–1.05] | 1.05† [1.05–1.05] | 1.05† [1.05–1.05] |

| Fasting glycemia (mmol/L) | 1.01† [1.01–1.01] | 1.01† [1.01–1.01] | 1.01† [1.01–1.01] |

|

| |||

| DISCRETE VARIABLES | OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] | OR [95%CI] |

|

| |||

| Male (vs. female) gender | 1.93† [1.87–2.00] | 1.99† [1.91–2.06] | 1.98† [1.91–2.06] |

| Living alone (vs. not living alone) | 1.07† [1.03–1.11] | 1.06† [1.03–1.10] | 1.06† [1.03–1.1] |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 0.77† [0.67–0.87] | 0.76† [0.66–0.86] | 0.76† [0.66–0.86] |

| 18.5–24.99 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25–29.99 | 1.73† [1.68–1.79] | 1.71† [1.66–1.77] | 1.71† [1.66–1.76] |

| ≥30 | 3.38† [3.23–3.54] | 3.27† [3.13–3.42] | 3.26† [3.12–3.41] |

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smokers | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Ex-smokers | 1.00 [0.97–1.04] | 1.02 [0.98–1.06] | 1.02 [0.99–1.06] |

| 1–10 cigarettes/day | 0.85† [0.81–0.89] | 0.86† [0.82–0.90] | 0.86† [0.82–0.90] |

| 11–20 cigarettes/day | 0.89† [0.84–0.93] | 0.87† [0.82–0.91] | 0.87† [0.83–0.91] |

| >20 cigarettes/day | 1.00 [0.93–1.08] | 0.99 [0.92–1.07] | 0.99 [0.93–1.07] |

| At-risk alcohol intake (see text) | 1.50† [1.43–1.57] | 1.51† [1.44–1.58] | 1.51† [1.44–1.58] |

| ≥1 hour of walking/day (vs. <1 hour) | 0.88† [0.86–0.91] | 0.92† [0.89–0.94] | 0.92† [0.89–0.94] |

| Familial history of hypertension | 1.46† [1.41–1.50] | 1.51† [1.46–1.55] | 1.51† [1.46–1.56] |

| Occupational status | |||

| High | Reference | Reference | |

| Medium | 1.22† [1.17–1.26] | 1.15† [1.09–1.22] | |

| Low | 1.58† [1.52–1.65] | 1.44† [1.34–1.54] | |

| Unemployed | 1.08‡ [1.02–1.14] | 0.97 [0.88–1.06] | |

| Unpaid occupation | 1.30† [1.21–1.41] | 1.13 [1.00–1.29] | |

| Other | 1.17 [0.85–1.61] | 1.08 [0.64–1.84] | |

| Occupational status × perceived stress | |||

| High × perceived stress | Reference | ||

| Medium × perceived stress | 1.09‡ [1.03–1.16] | ||

| Low × perceived stress | 1.15† [1.07–1.24] | ||

| Unemployed × perceived stress | 1.16† [1.06–1.27] | ||

| Unpaid occupation × perceived stress | 1.21‡ [1.07–1.37] | ||

| Other × perceived stress | 1.13 [0.64–1.99] | ||

BMI: Body Mass Index; BP: Blood Pressure; CI: Confidence Interval; OR: Odds Ratio; PSS-4: 4-item Perceived Stress Scale; QD2A: Questionnaire of Depression 2nd version Abridged; SD: Standard Deviation.

OR is given per 5-point increment for the PSS-4 and per unit for the other continuous variables.

P<0.001;

P<0.01.

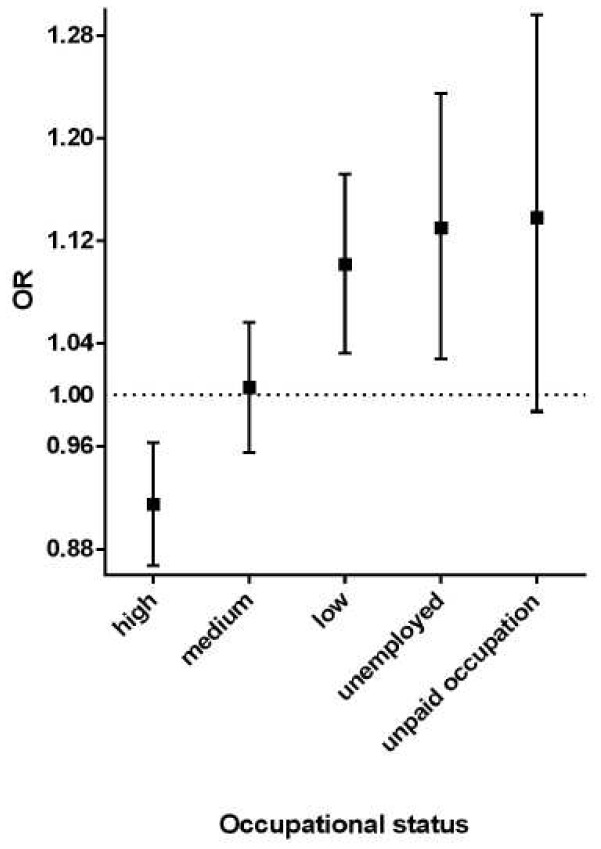

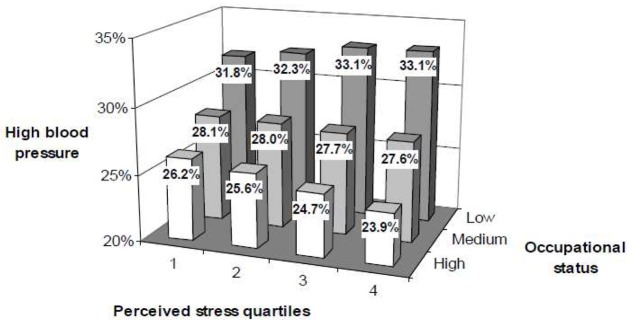

The interaction between perceived stress and occupational status was significant in model 3 (Table 1), suggesting that the association between perceived stress and high BP should be examined in each occupational category, separately. Adjusting for all other variables (i.e. model 1), perceived stress was negatively associated with high BP among participants with high occupational status (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.87–0.96) whereas this association was positive for those with low occupational status (OR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.03–1.17) and those who were unemployed (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.03–1.24) (Figures 1 and 2). The association between perceived stress and high BP was not significant among other occupational categories. In a post hoc analysis, we examined whether the OR significantly increased from high to low occupational status. Including only participants with high, medium or low occupational status, there was a significant interaction between perceived stress and occupational status taken as a linear variable (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Association between high BP (i.e. systolic BP ≥ 140 or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg) and perceived stress across occupational categories.

Odds Ratios (OR) are given per 5-point increment of the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale score (i.e. the difference between the 25th and the 75th percentile). OR among the “other” occupational category is not displayed owing to a wide, non significant 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2. Prevalence of high blood pressure according to perceived stress and occupational status among working participants.

Prevalence of high blood pressure (i.e. systolic BP ≥ 140 or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg) among working participants are given in % as a function of both perceived stress quartiles (4-item Perceived Stress Scale score) and occupational status.

In sensitivity analyses, similar patterns of results were obtained when participants who reported using antihypertensive drugs (considered as having high BP) or those with a history of cardiovascular or renal disease were included. Finally, we computed general linear models to examine the association of perceived stress with systolic and diastolic BP as continuous variables in each occupational category, separately. After adjustment for all variables, perceived stress was negatively correlated with systolic and diastolic BP among high status participants (regression coefficients: −0.531, p<0.001 and −0.226, p=0.019, respectively), positively with systolic and diastolic BP among low status participants (regression coefficients: 1.014, p=0.001 and 0.383, p=0.008, respectively), and positively with systolic BP among unemployed participants (regression coefficient: 0.750; p=0.007).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This cross-sectional study aimed to examine the association between perceived stress and high BP and to explore a potential moderating effect of occupational status. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to address this question and the first one to show that occupational status moderates the association between perceived stress and high BP outside the context of work site. Perceived stress was associated with high BP after adjustment for all variables except occupational status. Although this association disappeared after additional adjustment for occupational status, the interaction between occupational status and perceived stress was significant. In analyses stratified by occupational categories, perceived stress was negatively associated with high BP among participants of high occupational status, but positively associated among those of low occupational status and among the unemployed. Not surprisingly, perceived stress was higher among these two categories, thus explaining the lack of association between perceived stress and high BP when adjusting for occupational status. However, these differences may not account for the significant interaction between occupational status and perceived stress, as main effects were included in the model.

Explanatory hypotheses

Some neurobiological pathways may partially account for the links between current perceived stress, occupational status and high BP 22. The neural underpinnings of BP regulation are strikingly similar to those of emotion regulation 23,24, including (but not limited to) the serotonin system 25 and the interplay of the medial prefrontal cortex with the insula and the amygdala 26. This overlap may account for the well-known association between acute mental stress and a transient BP elevation 3. Interestingly, perceived social rank is associated with both anatomical and functional changes within this brain network 27. For instance, low perceived social rank is associated with increased amygdala reactivity to social stressors 27. The amygdala has a critical role in gating the sensitivity of the baroreflex through projections that inhibit the nucleus tractus solitarius and that activate the rostroventrolateral medulla 26. This provides a neurobiological model of how occupational status may moderate the association between perceived stress and high BP. This neurobiological model may underlie or complete other higher-level hypotheses.

First, perceived stress may partially result from work-related stress, which obviously relates to occupational categories. Occupational categories may differ in terms of exposure to job strain, which combines high job demands with low control at work 21, tends to be associated with both high BP and lower occupational category 16,28. Thus, among individuals of high occupational status, increased perceived stress may indeed relate to a more favorable ratio between job demands and job decision latitude, the contrary being true among their lower status counterparts. Higher decision latitude may thus overcome the impact of increasing stress on BP in the former, while lower decision latitude may even worsen it in the later. Although the detrimental effects of low decision latitude on health are well established 21, recent evidence suggests that high decision latitude may have positive effects on the biological underpinnings of stress such as cortisol level 29. Beyond job strain, perceived stress may also relate to exposure to occupational stressors that are specific to certain occupational categories (e.g. noise, cardiotoxic chemicals) and differently associated with the risk of hypertension 30,31.

Second, participants with lower occupational status might have been less likely to deal with stress with adaptive health behaviors (e.g. physical activity) and more with detrimental ones (e.g. alcohol consumption) 32. However, it is noteworthy that multivariate models were adjusted for health behaviors. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out this hypothesis regarding other unmeasured health behaviors such as dietary patterns or salt consumption.

However, these hypotheses do not account for the apparently “protective effect” of perceived stress among persons of high occupational status. A third hypothesis may build on the construct of emotional awareness, which is one’s ability to represent, discriminate, and elaborate one’s own emotional state 33. From a theoretical point of view, the perceived stress score results from two components: stress per se and the ability to be aware of it. A large body of evidence suggests that the former may have detrimental effects on health, whereas the latter may have beneficial effects 34. Higher occupational status is associated with greater emotional awareness 35. Among individuals of high occupational status, a high perceived stress score may thus partially result from a better emotional awareness, whereas among low status individuals, it could mostly result from higher levels of stress per se. This hypothesis is consistent with evidence for an association between essential hypertension and lower emotional awareness 36.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study are the large sample size allowing subsamples analyses and the wide set of covariates considered, including a measure of depressive mood. Some limitations should also be acknowledged. First, owing to the cross-sectional design of this study, no conclusion about causality can be drawn. For instance, hypertension may lead to higher stress due to medical complications. However, results were similar when including or excluding participants with cardiovascular or renal diseases. Furthermore, the first set of analyses excluded participants with treated, allegedly known hypertension. Finally, analyses were adjusted for perceived health status. Second, BP was not measured at several successive consultations. However, high BP has been associated with cardiovascular mortality in the IPC cohort study 37 as well as in other cohorts. Third, some potential confounders were not examined, such as salt consumption, ethnicity, social support and personality variables. Fourth, a large sample size ensures statistical power but not clinical significance because even small differences may reach statistical significance. Finally, the IPC cohort may not be representative of the general French population. Study recruitment was limited to the Paris area and two thirds of the participants were men, which potentially limits the generalizability of our results. Compared with Paris area inhabitants, individuals in the IPC cohort were less likely to live alone, and more likely to have a professional activity and a higher occupational status (http://www.recensement.insee.fr/home.action). In addition, they were seeking a preventive medical examination and thus may presumably display increased interest in their own health.

Perspectives

Our results extend to non-working individuals and broader aspects of stress the preliminary evidence that job strain may relate to BP at work to a different extent according to occupational status 16. Additionally, they suggest that higher perceived stress among individuals of high occupational status may relate to lower BP. Should these results be replicated with a prospective design, further studies would be warranted to elucidate the mechanisms of this interaction as such knowledge may eventually inform prevention strategies. Finally, our results urge researchers to systematically look for possible interactions with SES when examining the relationships between stress and hypertension. These interactions may account for some negative or equivocal results regarding the links between job strain, perceived stress and BP in previous studies 7,8,38. Our results may thus constitute an impetus for re-analyzing old datasets.

Novelty and Significance.

1). What Is New?

The association of stress with high blood pressure depends on occupational status.

2). What Is Relevant?

Previous conflicting results regarding the association between stress and hypertension may result from overlooking the moderating effect of socio-economic status indicators. Hypertension might partially explain the association between stress and cardiovascular diseases such as coronary heart disease and stroke among individuals of low occupational status or unemployed.

3). Summary

These results urge to systematically look for possible interactions with socio-economic status indicators when examining the relationships between stress and hypertension and may constitute an impetus for re-analyzing old datasets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés (CNAM-TS, France) and the Caisse Primaire d’Assurance Maladie de Paris (CPAM-P, France) for helping make this study possible.

Sources of funding

None.

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s) Statement

Sébastien Czernichow has received consultancy fees from Novo and Sanofi and lectures fees from Servier. Tabassome Simon has received unrestricted research grants from Astra-Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli-Lilly, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-aventis and Servier; speaker and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer-Schering, Eli-Lilly and Sanofi-aventis. Nicolas Danchin has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli-Lilly, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-aventis, Servier and The Medicines Company; advisory panels or lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Menarini, Merck-Serono, Novo-Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and Servier. Emmanuel Wiernik, Bruno Pannier, Hermann Nabi, Olivier Hanon, Jean-Marc Simon, Frédérique Thomas, Kathy Bean, Silla M. Consoli and Cédric Lemogne have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall IJ, Wolfe CDA, McKevitt C. Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ. 2012;345:e3953–e3953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chida Y, Hamer M. Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: a quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:829–885. doi: 10.1037/a0013342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparrenberger F, Cichelero FT, Ascoli AM, Fonseca FP, Weiss G, Berwanger O, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB, Fuchs FD. Does psychosocial stress cause hypertension? A systematic review of observational studies. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:12–19. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levenstein S, Smith MW, Kaplan GA. Psychosocial predictors of hypertension in men and women. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1341–1346. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markovitz JH, Matthews KA, Whooley M, Lewis CE, Greenlund KJ. Increases in job strain are associated with incident hypertension in the CARDIA Study. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:4–9. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparrenberger F, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB, Fuchs FD. Stressful life events and current psychological distress are associated with self-reported hypertension but not with true hypertension: results from a cross-sectional population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauvel JP, M’Pio I, Quelin P, Rigaud J-P, Laville M, Ducher M. Neither perceived job stress nor individual cardiovascular reactivity predict high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1112–1116. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102862.93418.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkleby MA, Ragland DR, Syme SL. Self-reported stressors and hypertension: evidence of an inverse association. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:124–134. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suter PM, Maire R, Holtz D, Vetter W. Relationship between self-perceived stress and blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:171–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildrum B, Romild U, Holmen J. Anxiety and depression lowers blood pressure: 22-year follow-up of the population based HUNT study, Norway. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nabi H, Chastang J-F, Lefèvre T, Dugravot A, Melchior M, Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A. Trajectories of depressive episodes and hypertension over 24 years: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Hypertension. 2011;57:710–716. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.164061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colhoun HM, Hemingway H, Poulter NR. Socio-economic status and blood pressure: an overview analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:91–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyer AR, Liu K, Walsh M, Kiefe C, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bild DE. Ten-year incidence of elevated blood pressure and its predictors: the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:13–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Pickering TG, Warren K, Schwartz JE. Lower socioeconomic status among men in relation to the association between job strain and blood pressure. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29:206–215. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesage F-X, Berjot S, Deschamps F. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25:178–184. doi: 10.2478/S13382-012-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pichot P, Boyer P, Pull CB, Rein W, Simon M, Thibault A. Un questionnaire d’auto-évaluation de la symptomatologie dépressive, le Questionnaire QD2: I. Construction, structure factorielle et propriétés métrologiques. Revue de Psychologie Appliquée. 1984;34:229–250. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pichot P, Boyer P, Pull CB, Rein W, Simon M, Thibault A. Un questionnaire d’auto-évaluation de la symptomatologie dépressive, le questionnaire QD2. II: Forme abrégée QD2A. Revue de psychologie appliquée. 1984;34:323–340. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemogne C, Thomas F, Consoli SM, Pannier B, Jégo B, Danchin N. Heart rate and completed suicide: evidence from the IPC cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:731–736. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182365dc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kivimäki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, Fransson EI, Heikkilä K, Alfredsson L, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Burr H, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Ferrie JE, Geuskens GA, Goldberg M, Hamer M, Hooftman WE, Houtman IL, Joensuu M, Jokela M, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Koskinen A, Kouvonen A, Kumari M, Madsen IE, Marmot MG, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Siegrist J, Singh-Manoux A, Suominen SB, Väänänen A, Vahtera J, Virtanen M, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, Zins M, Steptoe A, Theorell T IPD-Work Consortium. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;380:1491–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickering T. Cardiovascular pathways: socioeconomic status and stress effects on hypertension and cardiovascular function. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;896:262–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kober H, Barrett LF, Joseph J, Bliss-Moreau E, Lindquist K, Wager TD. Functional grouping and cortical-subcortical interactions in emotion: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2008;42:998–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemogne C, Gorwood P, Bergouignan L, Pélissolo A, Lehéricy S, Fossati P. Negative affectivity, self-referential processing and the cortical midline structures. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6:426–433. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaumann AJ, Levy FO. 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in the human cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:674–706. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gianaros PJ, Sheu LK. A review of neuroimaging studies of stressor-evoked blood pressure reactivity: emerging evidence for a brain-body pathway to coronary heart disease risk. Neuroimage. 2009;47:922–936. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal T, Alter A. Occupational stress and hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman GD, Lee JJ, Cuddy AJC, Renshon J, Oveis C, Gross JJ, Lerner JS. Leadership is associated with lower levels of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17903–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207042109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomei G, Fioravanti M, Cerratti D, Sancini A, Tomao E, Rosati MV, Vacca D, Palitti T, Di Famiani M, Giubilati R, De Sio S, Tomei F. Occupational exposure to noise and the cardiovascular system: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poreba R, Poreba M, Gać P, Andrzejak R. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and structural changes in carotid arteries in normotensive workers occupationally exposed to lead. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011;30:1174–1180. doi: 10.1177/0960327110391383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegrist J, Rödel A. Work stress and health risk behavior. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:473–481. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane RD, Schwartz GE. Levels of emotional awareness: a cognitive-developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:133–143. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lane RD. Neural substrates of implicit and explicit emotional processes: a unifying framework for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:214–231. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181647e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lane RD, Sechrest L, Riedel R. Sociodemographic correlates of alexithymia. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Consoli SM, Lemogne C, Roch B, Laurent S, Plouin P-F, Lane RD. Differences in emotion processing in patients with essential and secondary hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:515–521. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas F, Blacher J, Benetos A, Safar ME, Pannier B. Cardiovascular risk as defined in the 2003 European blood pressure classification: the assessment of an additional predictive value of pulse pressure on mortality. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1072–1077. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282fcc22b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ducher M, Cerutti C, Chatellier G, Fauvel J-P. Is high job strain associated with hypertension genesis? Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.