Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We sought to assess the individual and combined contribution of limbic and neocortical α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid to duration of illness in dementia with Lewy bodies.

METHODS

Quantitative image analysis of neocortical and limbic α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid was assessed in 49 patients with clinically probable dementia with Lewy bodies. Regression modelling examined the unique and shared contribution of each pathology to the variance of illness duration.

RESULTS

Patients with diffuse Lewy body disease had more severe pathology of each type and a shorter duration of illness than individuals with transitional Lewy body disease. The three pathologies accounted for 25% of the total variance of duration of illness, with 19% accounted for by α-synuclein alone or in combination with tau and β-amyloid. When the diffuse Lewy body disease group was examined separately, α-synuclein deposition exceeded that of tau and β-amyloid, and survival was not related to differences in tau or β-amyloid burden. In this model, 20% of 24% total variance in the model for duration of illness was accounted for independently by α-synuclein.

DISCUSSION

In dementia with Lewy bodies, the burden of α-synuclein is an important predictor of disease duration, both independently and synergistically with tau and β-amyloid.

Keywords: Lewy body, Alzheimer’s disease, pathology, parkinsonism, REM sleep behavior disorder, commonality analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

The histopathology of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is characterized by α-synuclein that accumulates in cell bodies as Lewy bodies, and in cell processes as Lewy neurites. Lewy-related pathology has two main distributions in DLB. For some patients, it is predominantly located in brainstem, subcortical and limbic regions, while for others it is also diffusely distributed to neocortical regions in additon to brainstem, subcortical and limbic regions [1]. Neuropathologic heterogeneity of DLB is further complicated by the co-occurence of Alzheimer disease (AD)-related pathology. Extracellular β-amyloid diffuse plaques and senile plaques with tau-positive neurites can commonly occur in DLB [2, 3]. Although the density and distribution of neurofibrillary tangle pathology is typically less in DLB than AD [4, 5], some DLB patients have many neurofibrillary tangles [6]. In Parkinson’s disease, the extent of the Lewy-related pathology on its own, and additively with tau and β-amyloid, correlates with development of dementia [7–10]. Less is known about the role of these misfolded proteins in the clinical presentation and disease course of DLB. Understanding the contribution of these protein aggregates to DLB is important, particularly as antemortem imaging markers are being developed for each protein [11], and as the field moves forward to develop disease-modifying therapies designed to target specific proteins.

Patients with DLB tend to have a shorter survival than those with AD [5]. Rapid disease progression in DLB is often attributed to the cortical AD-related pathology [12, 13], though this is not consistently found [14]. The role of α-synuclein may be underestimated when sampling is restricted to neocortical regions or in studies that do not quantify Lewy neurites. Also, there may be additive or synergistic effects of co-occuring Lewy-related and AD-related pathologies that may not be evident when examining the independent contributions of each pathology [15–17]. In order to obtain a more representative quantitative measure of the neuronal and neuritic burden of α-synuclein and tau, and of extracellular β-amyloid, this study used image analysis techniques. This approach allows for a more accurate estimate of pathology than semi-quantitative or staging rubrics [18], and provides the opportunity to assess the separate and combined contribution of pathologies to duration of illness.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Participants who met criteria for clinically probable DLB (n=49) were recruited from the Memory Disorders and Movement Disorders Clinics and followed prospectively through the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. Annual clinical visits incorporated a clinical interview, neurologic examination, neuropsychological assessment, and a series of informant questionnaires. If the patient was untestable or unable to come to the clinic, we carried out a telephone interview and obtained the informant questionnaires. The diagnosis of DLB was made on the basis of the current criteria and required dementia plus 2 of 4 clinical features (visual hallucinations, fluctuations, parkinsonism, REM Sleep Behavior Disorder) [19, 20]. A non-cognitive rating of dementia severity was assessed with the Global Deterioration Scale (GLDS) [21]. The presence of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder was obtained through a clinical interview and the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire [22]. The presence of fluctuations was based on a score of 3 or 4 on the 4-item Mayo Fluctuations Scale [23]. The presence of parkinsonism was based on neurologic examination, and presence of 2 of 4 cardinal features of bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor and postural instability. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale was used to objectively quantify parkinsonism severity [24]. Duration of illness was operationalized to represent the temporal interval from the estimated onset of cognitive impairment to time of death. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and informed consent for participation was obtained from every subject and/or an appropriate surrogate.

2.2 Neuropathologic assessments

All cases underwent neuropathologic assessment that included macroscopic and microscopic evaluation. Brains were sampled using a systematic and standardized protocol, in which neocortical samples were taken prior to brain dissection to assure uniformity of sampling and to obtain orthogonal sections of the cortical ribbon. Tissue sections were embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm thick sections were mounted on glass slides for histological examination and immunohistochemistry. Thioflavin-S fluorescent microscopy was used to assess AD-related pathology, which included counts of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and senile plaques in 6 cortical regions, 4 sectors of the hippocampus, 2 subregions of the amygdala and the basal nucleus of Meynert. Braak NFT stage [25] and Thal amyloid phase [26] were assigned based upon the distribution of NFT and senile plaques respectively, using previously published methods [27]. For diagnostic and staging purposes, immunohistochemistry was performed on all cases with an α-synuclein antibody (NACP, 1:3000 rabbit polyclonal, Mayo Clinic antibody) using a protocol (formic acid pretreatment and DAKO DAB polymer signal detection) that has been shown to be comparable, or better, than other methods [28]. Counts of Lewy bodies (at x200 magnification) were assessed in middle frontal, superior temporal, inferior parietal, cingulate and parahippocampal cortices, as well as the amygdala. Semi-quantitative ratings of the extent of the α-synuclein pathology and neuronal loss were made in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, substantia nigra and locus ceruleus..

When assigning subtypes of Lewy body disease, the presence, density, semi-quantitative scores and distribution of Lewy-related pathology followed recommendations of the Third Consortium for DLB criteria [19]. Transitional Lewy body disease (TLBD) included individuals with Lewy-related pathology in brainstem and predominantly limbic regions, and diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD) included those with Lewy-related pathology in brainstem, limbic, and neocortical regions [19]. Patients were assigned a neuropathologic likelihood of DLB based on Lewy body disease subtype and severity of concurrent AD-type pathology according to Third Consortium for DLB criteria, as validated in a previous study [29].

2.3 Image analysis

Quantitative image analysis of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid burden was performed in five neocortical regions of interest (middle frontal, inferior parietal, occipitotemporal, inferior temporal and visual association cortices (Brodmann area 18), and in three limbic regions of interest (parahippocampal and cingulate cortices and the amygdala) (see Fig. 1). Hippocampal regions were assessed, but excluded from this analysis given the presence of significant inter-correlations with limbic regions. Immunohistochemistry was performed on a DAKO Autostainer (Universal Staining System, Carpinteria, CA) with the following antibodies: α-synuclein (LB509, 1:100, mouse monoclonal, Zymed, San Francisco, CA), phosphorylated tau (PHF-1, 1:1000, mouse monoclonal, gift from Dr. Peter Davies, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System), and β-amyloid (4G8, 1:50000, mouse monoclonal, BioSource International/Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Sections processed for LB509 were pretreated with steam (distilled water) and protease (Sigma protease XXIV; 0.25 mg/ml). Sections processed for 4G8 were pretreated with 95% formic acid and steam (distilled water), and sections processed for PHF-1 were pretreated with steam (distilled water) alone. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin after immunostaining. Stained slides were digitally scanned at x20 magnification on the Aperio ScanScope AT2 (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) and were viewed and annotated using ImageScope v10.2 software (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). A region of interest (ROI) was outlined for each brain region, and two ROIs were outlined (dorsal and ventral side) in the visual association cortex. The final value for visual association cortex for each case was the average of the two fields. To count the number of pixels that were strongly stained by the DAB chromogen, two custom positive-pixel count algorithms (for LB509 and 4G8) and a custom color-deconvolution algorithm (for PHF-1) were designed. The result was a percentage burden that reflected the amount of stained pathology in the total area examined. Investigators were blinded to the clinical status during image analysis procedures. This approach captures perikaryl and neuritic α-synuclein, phosphorylated tau (including tau-positive neurites within senile plaques), and extracellular β-amyloid within diffuse and neuritic senile plaques. It is sensitive to tau of all morphologic types, does not select for any particular structure and has been used in other studies to measure tau burden in AD [30]. When we apply the plaque and tangle data of the prospective DLB cohort to the algorithm we developed to distinguish typical AD from atypical AD, 18 cases in the DLB prospective cohort failed criteria for AD because of zero cortical tangles, 2 had a limbic predominant pattern, and none of the cases had hippocampal sparing AD which is typically associated with severe cortical tau pathology. There were significant correlations between PHF1 burden and Braak NFT stage for cortical (range from r = 0.70 to r = 0.83, p<0.01) and limbic regions (range from r = 0.73 to r = 0.80, p<0.01). There were also significant correlations between 4G8 burden and Thal amyloid phase for cortical (range from r = 0.60 to 0.79, p<0.01) and limbic regions (range from r = 0.79 to 0.85, p<0.01).

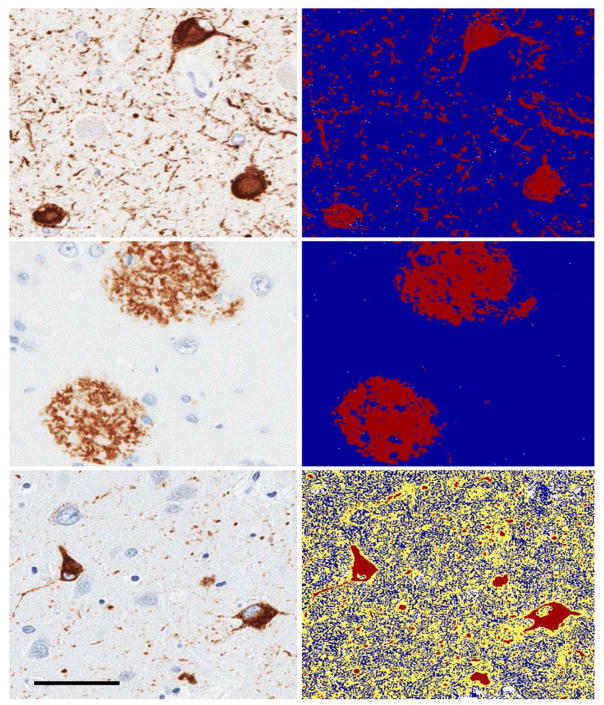

Fig. 1. Digital Pathology for α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid.

Image analysis for α-synuclein, β-amyloid and tau. Panels on the left indicate immunohistochemistry for each antibody and panels on the right represent the digital scans of the images used for pixel count algorithms resulting in a percentage burden reflecting the amount of stained pathology in the area examined.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were carried out, and group comparisons used Student’s t--tests, Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples and Wilcoxin-signed rank test for within group comparisons as appropriate. Chi--square tests were used for group comparisons of categorical variables, and Spearman rank correlations were used to examine inter-relationships. To facilitate group comparisons of pathologic burden while avoiding multi-collinearity due to the high correlation between limbic and cortical burden scores, we calculated a summative cortical and limbic burden score for each pathology. This was composed of the sum of the mean neocortical burden plus the mean limbic burden, resulting in an α-synuclein cortical-limbic burden score, a tau cortical-limbic burden score, and a β-amyloid cortical-limbic score. A total burden score was also calculated that represented the sum of these three cortical-limbic burden scores. Multiple linear regression analyses were carried out for the entire sample (n=49) and for the DLBD-only group (n=34) to model the relationships between the three pathology types and duration of illness. To clarify the individual and combined contribution of the three pathologic independent variables, a commonality analysis [31] for each regression model was undertaken. This method of variance partitioning was used to identify the proportion of variance of duration of illness uniquely associated with the mean cortical-limbic burden of each pathology, and the proportions attributed to the shared or common variance of each possible combination of α-synuclein, tau, and β-amyloid. A subsequent regression analysis that controlled for sex and death age was also carried out to assess the sensitivity of results to inclusion of these variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Demographic and Clinical Features of TLBD and DLBD

The neuropathologic designations of high and intermediate likelihood DLB [19] were made in 55% and 45% of the sample, respectively. Since these designations intermix neocortical Lewy- and AD-related pathologies, we did not use these classifications further. Table 1 compares TLBD and DLBD in demographic, clinical and pathologic staging variables. All patients had a history of dementia, and as such, duration of illness was characterized as the estimated onset of cognitive decline to date of death. Two patients with DLBD and two with TLBD had motor symptoms that started more than a year before the estimated onset of cognitive symptoms. Duration of illness was significantly shorter for patients with DLBD compared to TLBD. There was no difference in the number or onset of core DLB features between TLBD and DLBD. The frequency of APOE ε4 genotype did not differ between TLBD and DLBD, but those with the ε4 allele had greater β-amyloid burden (p<0.05) and a shorter duration of illness (p<0.04) than those without an ε4 alelle.

Table 1.

Clinical, demographic and pathologic staging variables. Values represent mean ± sd or %, p values represent Student’s t-test or Chi-square comparisons.

| TLBD | DLBD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15 | 34 | |

| Males, n(%) | 13(87%) | 27(79%) | 0.55 |

| Estimated Age of Cognitive Onset, years | 64.3 ± 8.4 | 69.3 ± 6.7 | 0.06 |

| Death age, years | 73.2 ± 8.4 | 75.7 ± 6.6 | 0.25 |

| Number of Visits | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.6 | 0.35 |

| Mean years of follow--up | 3.9 ± 3.2 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 0.05 |

| Duration of illness relative to estimated onset of cognitive decline, years | 9.0 ± 3.7 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | <0.01 |

| Time from last evaluation to death, months | 11.3 ± 12.4 | 14.6 ± 14.9 | 0.46 |

| Baseline mean Global Deterioration Scale score | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 0.05 |

| Last visit mean Global Deterioration Scale score | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 0.23 |

| Number of Core Features | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 0.70 |

| Visual hallucinations (VH), n(%) | 11(73%) | 29(85%) | 0.43 |

| Onset of VH relative to estimated onset of cognitive decline, years | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 0.99 |

| Fluctuations, n(%) | 13(87%) | 32(94%) | 0.38 |

| Parkinsonism, n(%) | 15(100%) | 28(82%) | 0.08 |

| Onset of parkinsonism relative to estimated onset of cognitive decline, years | 0.8 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 2.3 | 0.51 |

| Baseline Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parkinsonism severity, years | 11.6 ± 6.8 | 9.3 ± 6.9 | 0.30 |

| REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD), n(%) | 14(93%) | 29(85%) | 0.43 |

| Onset of RBD relative to estimated onset of cognitive decline, years | −9.6 ± 17.7 | −6.9 ± 10.3 | 0.54 |

| APOE e4 positive genotype, n(%) | 5(33%) | 18(53%) | 0.17 |

| Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Thal β-amyloid-β stage | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | <0.01 |

3.2 Limbic and neocortical distribution of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid

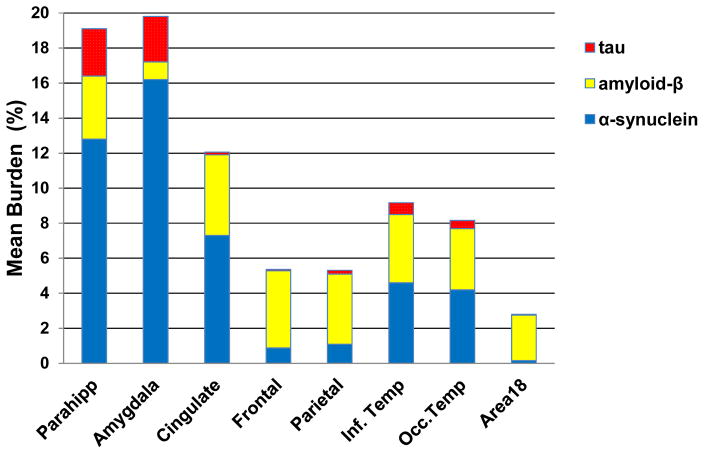

The regional pathologic burden for each sampled area and the summative cortical-limbic burden scores are presented in Table 2. In limbic regions, α-synuclein burden was greater in the parahippocampal gyrus and amygdala compared to the cingulate gyrus (p<0.01), and the same pattern was evident for tau, but with less pathologic burden (p<0.01) (see Fig. 2). In contrast, parahippocampal and cingulate gyri had greater β-amyloid burden than the amygdala (p<0.01). In neocortical regions, α-synuclein burden was significantly greater in both the occipitotemporal and inferior temporal cortices (p<0.01) compared to the other cortical regions. Neocortical tau pathology was significantly less than the other pathologies (p<0.01), with a pattern of greater tau burden in the ventral temporal cortices relative to other cortical regions (p<0.01). Neocortical amyloid-β burden was relatively uniform and did not significantly differ across the sampled regions (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Regional pathologic burden. Values represent mean ± sd, and median (interquartile range).

| Area | α-Synuclein | Tau | β-Amyloid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limbic burden | 15.9 ± 12.5 13.9 (5.4 – 22.7) |

4.8 ± 6.1 2.1 (0.4 – 7.8) |

3.4 ± 2.2 3.7 (1.2 – 5.3) |

| Amygdala | 18.7 ± 13.7 16.2 (7.5 – 28.2) |

6.8 ± 9.7 2.6 (0.1 – 9.9) |

1.3 ± 1.2 1.0 (0.4 – 2.1) |

| Cingulate gyrus | 11.7 ± 11.9 7.3 (3.1 – 19.2) |

1.1 ± 2.7 0.2 (0.05 – 0.7) |

4.0 ± 2.7 0.6 (1.3 – 5.8) |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 18.1 ± 16.6 12.8 (3.8 – 26.5) |

7.2 ± 9.3 2.7 (0.6 – 11.9) |

3.7 ± 2.3 3.6 (1.9 – 5.6) |

| Cortical burden | 3.5 ± 4.5 1.9 (0.4 – 4.2) |

2.3 ± 3.8 0.3 (0.04 – 3.4) |

3.3 ± 2.0 3.7 (1.8 – 5.1) |

| Middle Frontal | 3.1 ± 6.2 0.9 (0.4 – 3.0) |

1.5 ± 3.9 0.1 (0.2 – 0.6) |

4.1 ± 2.5 4.4 (1.7 – 5.9) |

| Inferior Parietal | 1.7 ± 2.0 1.1 (0.2 – 2.3) |

2.6 ± 6.3 0.2 (0.1 – 2.0) |

3.5 ± 2.2 4.0 (1.4 – 5.0) |

| Occipitotemporal | 7.6 ± 9.5 4.6 (0.8 – 10.0) |

3.8 ± 5.4 0.7 (0.1 – 6.2) |

3.7 ± 2.3 3.9 (1.7 – 5.7) |

| Inferior Temporal | 5.8 ± 7.5 4.2 (0.6 – 7.1) |

3.0 ± 5.5 0.5 (0.04 – 3.2) |

3.4 ± 2.3 3.5 (2.0 – 4.8) |

| Occipital (BA 18) | 0.31 ± 0.36 0.1 (0.1 – 0.4) |

0.47 ± 1.3 0.03 (0.02 – 0.2) |

2.2 ± 1.5 2.6 (0.5 – 3.3) |

| Cortical-Limbic Burden Sum of mean Cortical and mean Limbic burden | 19.4 ± 16.5 | 7.1 ± 9.7 | 6.8 ± 4.3 |

| Mean of Median Burden Sum of median Cortical and median Limbic burden | 18.5 ± 16.4 | 6.7 ± 10.4 | 7.0 ± 4.4 |

Fig. 2.

Regional distribution of the pathologies. Parahipp = parahippocampal gyrus, Cingulate = cingulate gyrus, Frontal = middle frontal gyrus, Parietal = inferior parietal gyrus, Inf. Temp = inferior temporal gyrus, Occ. Temp = Occipitotemporal gyrus, Occipital = Visual Association Cortex.

3.3 Limbic and neocortical intercorrelations in TLBD and DLBD

In TLBD, there was insufficient neocortical α-synuclein (by definition) to examine limbic and neocortical correlations. Neocortical tau was also sparse-to-absent in TLBD (≤ 0.1% neocortical tau). In TLBD, limbic and neocortical β-amyloid were highly correlated (r = 0.89, p<0.01), indicating that individuals with greater limbic β-amyloid burden tended to have greater neocortical β-amyloid burden.

In DLBD, limbic and neocortical correlations were high for each protein (α-synuclein: r = 0.84, tau: r = 0.87, β-amyloid: r = 0.87; all p<0.01). To avoid multi-collinearity while maximizing the power of the available data in order to model the contribution of limbic and neocortical pathology to duration of illness, we calculated separate summative neocortical and limbic burden scores for α-synuclein, tau, and β-amyloid. For each pathology, this score represents the sum of the average neocortical burden plus the average limbic burden. This measure was used for all subsequent analyses.

3.4 Burden comparisons of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid

There were significant correlations between α-synuclein and tau burdens (r = 0.59, p<0.01), between α-synuclein and β-amyloid burdens (r = 0.53, p<0.01), and between tau and β-amyloid burdens (r = 0.65, p<0.01), indicating that patients with greater pathology of one type also tended to have greater pathology of the other types. DLB patients with a Braak NFT stage of IV or higher had a greater burden of α-synuclein (p=0.02), tau (p<0.01) and amyloid-β (p<0.01) compared to those with a Braak NFT stage of III or less. This suggests that patients with a greater distribution of neurofibrillary tangle pathology also have greater deposition of α-synuclein, tau, and β-amyloid.

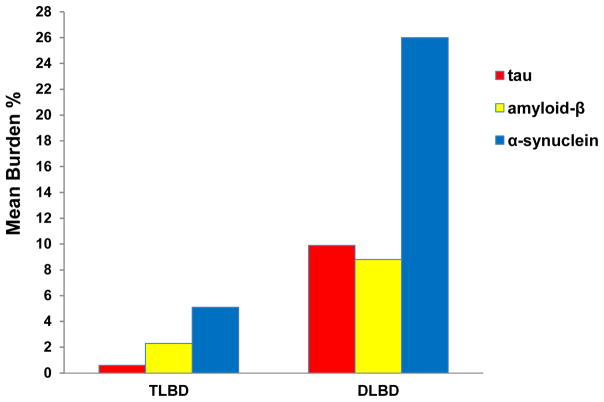

The burden of each protein was significantly greater in DLBD compared to TLBD (p<0.01, Fig. 3), with the DLBD group harboring greater overall pathology. Specific comparisons in TLBD revealed greater α-synuclein burden compared to tau (p<0.01), greater α-synuclein compared to β-amyloid (p=0.03), and greater β-amyloid compared to tau (p=0.03). In DLBD, the α-synuclein burden was greater than both tau (p<0.01) and β-amyloid (p<0.01), but burdens of tau and β-amyloid were similar in limbic and neocortical regions (p=0.49).

Fig. 3. Mean burden of limbic and cortical pathology.

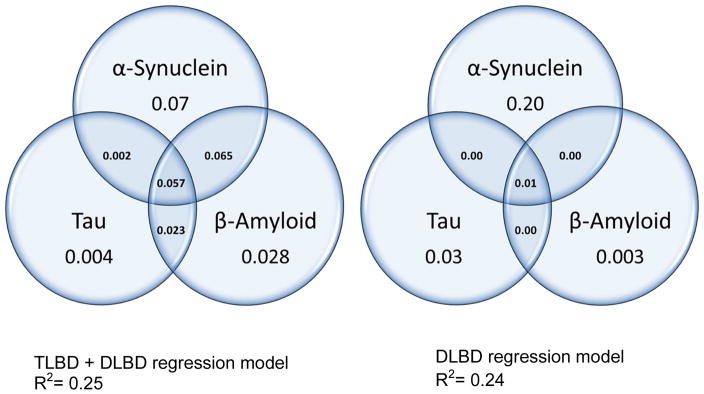

Regression commonality analysis for the TLBD and DLBD group and for DLBD-only group. Values represent the unique and shared variance accounted for by each pathology type for duration of illness.

3.5 The contribution of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid burden to duration of illness

In the TLBD + DLBD sample, duration of illness was correlated with the cortical-limbic burden of α-synuclein (r = −0.36, p<0.01), tau (r = −0.31, p=0.03), β-amyloid (r = −0.30, p=0.03) and with the total cortical-limbic pathologic burden across pathologies (r = −0.46, p<0.01). In the DLBD-only sample, duration of illness was correlated with α-synuclein (r = −0.37, p<0.01) and with the total cortical-limbic burden across pathologies (r = −0.45, p<0.01), but not with tau (r = −0.22, p=0.21) or β-amyloid (r = −0.05, p=0.77).

Linear regression analyses were carried out for the TLBD + DLBD model and for the DLBD-only model (see Table 3). These models indicate that a quarter of the variance of illness duration was accounted for by the summative neocortical and limbic burden of Lewy-related and AD-related pathologies. In the TLBD+DLBD model, the total variance accounted for by α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid was estimated to be R2=25%. A commonality analysis was used to deconstruct the regression effects of each model to identify the unique variance of duration of illness accounted for by each of three individual pathologies, as well as the shared variance associated with each possible combination (Fig. 4). Results from the TLBD+DLBD model revealed that α--synuclein had a unique contribution of 7%, the shared contribution of α-synuclein with tau or β-amyloid was 12.4%, and the unique and shared contribution of tau or β-amyloid alone was 6%. Altogether, of the 25% of the variance of duration of illness, 19% was accounted for by α-synuclein alone or commonly with tau and β-amyloid. When regression analyses controlled for the effects of sex and age at death, the change in R2 was 0.001 for sex (p>0.05) and the change in R2 was 0.009 for age at death (p>0.05), and did not qualitatively affect the contributions of pathology to duration of illness.

Table 3.

Multiple Hierarchical Linear Regression for Duration of Illness. TLBD=transitional Lewy body disease, DLBD=diffuse Lewy body disease

| Model with TLBD and DLBD | R2 | Standard error | Change in R2 | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | 0.09 | 3.05 | 0.09 | 4.48 | 0.04 |

| Tau, β-Amyloid | 0.18 | 2.92 | 0.09 | 5.26 | 0.03 |

| Tau, β-Amyloid, α-Synuclein | 0.25 | 2.82 | 0.07 | 4.4 | 0.04 |

| ANOVA for Tau, β-Amyloid, α-Synuclein model | --- | --- | --- | 5.1 | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Model with DLBD-only | R2 | Standard error | Change in R2 | F | P |

|

| |||||

| Tau | 0.04 | 2.53 | 0.04 | 1.42 | 0.24 |

| Tau, β-Amyloid | 0.04 | 2.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Tau, β-Amyloid, α-Synuclein | 0.24 | 2.33 | 0.20 | 7.69 | <0.01 |

| ANOVA for Tau, β-Amyloid, α-Synuclein model | --- | --- | --- | 3.12 | 0.04 |

Fig. 4.

Commonality analysis

In the DLBD-only model, the total variance of the model accounted for by pathology was estimated to be R2=24% (Fig. 4). In this subgroup, the unique contribution of α-synuclein was even more pronounced, with 20% of disease duration accounted for by α-synuclein alone, 1% accounted for by the combination of α-synuclein with tau and β-amyloid, and 3% accounted for by tau and β-amyloid, only. To better understand this finding, we compared the burden of each pathology in DLBD patients with short and long duration of illness (≤ 6 years n=15 vs ≥ 7 years n=19). Individuals with a short duration of illness had significantly greater α-synuclein (35.7 ± 17 vs. 18 ± 9; p<0.01), but did not differ in tau or amyloid-β burdens (p>0.05). The DLBD-only model had less range of pathology compared to the TLBD+DLBD model, and the narrower range of AD--related pathology in the context of more severe Lewy-related pathology may account, in part, to the stronger independent predictive value of α-synuclein to that of tau or β-amyloid on duration of illness in DLBD.

4. DISCUSSION

In a prospectively studied autopsy cohort of patients with clinically probable DLB, those with diffuse neocortical Lewy-related pathology (i.e., DLBD) had a more rapid disease course and a greater burden of limbic and neocortical α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid than those with predominantly brainstem and limbic Lewy-related pathology (i.e., TLBD). We were interested in understanding the individual and combined contributions of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid pathologic burdens to duration of illness. When the model was characterized by both TLBD and DLBD (and as such included a wide range of pathology burden from minimal to extensive) α-synuclein was a significant contributor, both independently and additively with neocortical and limbic tau and β-amyloid (Fig. 4). Specifically, the three pathologies accounted for a quarter of the total variance of duration of illness, with 19% accounted for by α-synuclein either uniquely (7%) or in combination with tau and β-amyloid (12.4%). This model indicates that when TLBD and DLBD are examined together, α-synuclein contributes to an accelerated disease course as an individual predictor and synergistically with tau and amyloid-β. This suggests that although the presence and severity of AD-related pathology in DLB affects prognosis, it occurs largely within the context of a synergistic or additive effect with α-synuclein.

When DLBD was examined separately, mean cortical and limbic burden scores for α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid again accounted for a quarter of the total variance of duration of illness. In this model, the individual contribution of α-synuclein was the strongest pathologic predictor of disease duration. Specifically, the unique contribution of α-synuclein was even more pronounced, with 20% of the variance of disease duration independently accounted for by α-synuclein, 1% accounted for by the combination of α-synuclein with tau and β-amyloid, and 3% accounted for by tau and β-amyloid, only. The finding that α-synuclein has greater independent predictive value for duration of illness in DLBD can be explained by less heterogeneity of AD-related pathology in DLBD compared to the TLBD + DLBD group and because the burden of α-synuclein greatly exceeded that of the AD-related pathologies. These data provide clear evidence of the important contribution of neuronal and neuritic α-synuclein burden to duration of illness.

In our cohort, DLB patients who had a greater burden of α-synuclein also had greater burdens of tau and β-amyloid [9, 15, 32, 33]. The distribution of pathology exhibited the well-established pattern of greater limbic vulnerability and regional overlap of limbic α-synuclein and tau [5, 34] (Fig. 2). Other studies have shown co-aggregation of α-synuclein and tau in the same neuronal populations [34–36], which may augment the deterioration of those cells. In contrast, β-amyloid deposition was markedly greater than tau and more uniformly distributed across sampled areas. Whether β-amyloid has a generalized promoting or synergistic effect on α-synuclein has yet to be determined, but animal models suggest that this might be the case [37].

One way the pathologies may promote the accumulation of each other is through the seeding and fibrilization that is involved in cell-to-cell spreading of aggregated α-synuclein [38]. The first evidence that α-synuclein pathology might spread through neuronal pathways was identified in post-mortem Parkinson’s disease patients who received transplants of embryonic mesencephalic tissue grafts a decade earlier [39, 40]. Since then, intracerebral injection of brain extracts from patients with α-synucleinopathies have been shown to trigger pathologic intracellular α-synuclein in rodents and in non-human primates [41, 42]. Models of cell-to-cell propagation have shown that α-synuclein can interact with β-amyloid and tau to promote [43, 44] or inhibit accumulation of each other [45, 46]. To date, two distinct strains of α-synuclein have been found with evidence of differences in structural conformation (fibrils vs. ribbons), binding affinity, the propensity to seed and propagate, resistance to clearance, and in their ability to cross-seed and promote the fibrillization of tau [46–48]. We do not know if the α-synuclein in DLB includes different strains, but this is a compelling hypothesis that has the potential to explain the pathologic heterogeneity of DLB and associated differences in disease duration.

Our results indicate that despite differences in the regional distribution and severity of pathology, patients with either TLBD or DLBD can present with dementia and the core clinical features of DLB. In other words, despite harboring sparse-to-no neocortical pathology, dementia was evident in each patient with TLBD, and 80% of the group had moderate-to-severe dementia at the last evaluation. Also, the presence and onset of four core clinical features of DLB during life (visual hallucinations, parkinsonism, fluctuations, REM sleep behavior disorder) was similar between TLBD and DLBD. This confirms that brainstem and limbic pathology is sufficient for the development of the four core DLB clinical features, but also that cognitive impairment in DLB does not require pathologic spread to neocortical regions [49, 50]. How do we reconcile these findings with prior studies showing a relationship between neocortical pathology and improved DLB diagnostic accuracy, or with findings that show a relationship between neocortical pathology and an increased likelihood of dementia in Parkinson’s disease [7, 51–53]? Our data indicate that DLB patients with neocortical pathology also have greater limbic pathology, and one explanation may be that the greater overall pathologic burden, which includes greater limbic pathology, may lower the threshold for the emergence or detection of cognitive difficulties and core DLB features in Lewy body disease.

A strength of this study included the use of image analysis techniques to quantitatively assess intraneuronal and neuritic α-synuclein, intraneuronal and neuritic tau, and extracellular β-amyloid. This served the goal of obtaining a more accurate estimate of the severity of the pathology than may be possible through counts, semi-quantitative ratings or staging systems. Nonetheless, we did not distinguish between neuritic plaques and diffuse β-amyloid plaques, and further work is needed to characterize the contribution of plaque subtypes.

Sample size was a limitation of the study. Future studies with a larger sample size would allow for a more detailed examination of pathologic subgroups and would also permit investigation of other factors that may affect survival, including but not limited to neurochemical and synaptic indices of neuronal loss, cerebrovascular disease, and genetic markers. Another limitation pertained to the use of duration of illness as a proxy for disease severity. The three pathologies accounted for a quarter of the total variance of duration of illness, which is modest when considering the many neurologic and non-neurologic factors unrelated to pathology may also shorten life. Further investigations are needed to determine if other clinical indicators of disease trajectory, such as rates of cognitive or functional decline, also show a more rapid decline associated with pathology burden and regional distribution and burden of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid. Developing a better understanding of the relationship between the specific proteins and disease expression will be critical as the field advances to develop protein-specific therapeutic interventions in DLB. Although many neurologic and non-neurologic factors may influence survival, these data reveal that α-synuclein is the most important pathologic predictor of duration of illness in DLB. It contributes independently to accelerated disease course, but it also has an additive or synergistic contribution with tau and β-amyloid.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

1. Systematic review

We conducted a comprehensive literature review using PubMed and Medline. The pathologic contribution to duration of illness in Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies has been studied using semi-quantitative staging approaches that has typically been restricted to neocortical regions and has not included an assessment of neuritic pathology. Quantitative image analysis provides a more accurate assessment of pathologic burden, but only a few studies have used this technique in Parkinson’s disease and none have used it to examine dementia with Lewy bodies.

2. Interpretation

Greater cortical-limbic α-synuclein burden was the strongest predictor of shorter disease duration, both individually and synergistically with tau and β-amyloid.

3. Future Directions

Other indicators of disease duration, such as rate of cognitive decline and rate of functional decline need to be assessed in relation to individual and combined contribution of protein aggregates. This has relevance for monitoring disease progression as protein-specific therapies are developed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and families for their contributions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: P50-AG016574 to BFB, DWD, JEC, KK, MEM, NGR, TJF and P50-NS072187 to DWD, JAVG, RJU, ZKW, by the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy body research to BFB, DWD, KK, TJF, OP and by the Uehara Memorial Foundation to NA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Conception and design of the study (TJF, NA, DWD), acquisition of data (TJF, NA, DWD, RJU, ZW, NGR, JAVG, OP), analysis of data (TJF, JEC), drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures (TJF, NA, DWD, JGR, NGR, KK, MEM, JEC, BFB).

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

Drs. Ferman, Aoki, Kantarci, Van Gerpen, J. Graff-Radford, Pedraza, Murray and Dickson report no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Boeve has served as an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by GE Healthcare, FORUM Pharmaceuticals and C2N Diagnostics. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009). He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Tau Consortium.

Dr. N. Graff-Radford serves on a scientific advisory board for Codman; serves on the editorial boards of The Neurologist and Alzheimer Disease and Therapy; has received publishing royalties from UpToDate, Inc.; and receives research support from Biogen, Lilly and Axovant. He has consulted for Cytox.

Dr. Wszolek is supported by The Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation and James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Fund, and The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust.

Dr. Uitti serves as an Associate Editor for Neurology,® receives research funding from Boston Scientific.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marui W, Iseki E, Kato M, Akatsu H, Kosaka K. Pathological entity of dementia with Lewy bodies and its differentiation from Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:121–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0869-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujishiro H, Iseki E, Higashi S, Kasanuki K, Murayama N, Togo T, et al. Distribution of cerebral amyloid deposition and its relevance to clinical phenotype in Lewy body dementia. Neurosci Lett. 2010;486:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen LA, Masliah E, Galasko D, Terry RD. Plaque-only Alzheimer disease is usually the lewy body variant, and vice versa. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:648–54. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199311000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deramecourt V, Bombois S, Maurage CA, Ghestem A, Drobecq H, Vanmechelen E, et al. Biochemical staging of synucleinopathy and amyloid deposition in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:278–88. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000205145.54457.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker L, McAleese KE, Thomas AJ, Johnson M, Martin-Ruiz C, Parker C, et al. Neuropathologically mixed Alzheimer’s and Lewy body disease: burden of pathological protein aggregates differs between clinical phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:729–48. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gearing M, Lynn M, Mirra SS. Neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer disease with Lewy bodies: two subgroups. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:203–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horvath J, Herrmann FR, Burkhard PR, Bouras C, Kövari E. Neuropathology of dementia in a large cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Rel Disord. 2013;19:864–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurtig HI, Trojanowski JQ, Galvin J, Ewbank D, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, et al. Alpha-synuclein cortical Lewy bodies correlate with dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2000;54:1916–21. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin DJ, White MT, Toledo JB, Xie SX, Robinson JL, Van Deerlin V, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:587–98. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toledo JB, Gopal P, Raible K, Irwin DJ, Brettschneider J, Sedor S, et al. Pathological α-synuclein distribution in subjects with coincident Alzheimer’s and Lewy body pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:393–409. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1526-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, et al. Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2091–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halliday G, Hely M, Reid W, Morris J. The progression of pathology in longitudinally followed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:409–15. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jellinger KA, Wenning GK, Seppi K. Predictors of survival in dementia with lewy bodies and Parkinson dementia. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:428–30. doi: 10.1159/000107703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams MM, Xiong C, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1935–41. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247041.63081.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compta Y, Parkkinen L, O’sullivan SS, Vandrovcova J, Holton JL, Collins C, et al. Lewy-and Alzheimer-type pathologies in Parkinson’s disease dementia: which is more important? Brain. 2011;134:1493–505. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howlett DR, Whitfield D, Johnson M, Attems J, O’Brien JT, Aarsland D, et al. Regional multiple pathology scores are associated with cognitive decline in Lewy body dementias. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:401–8. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Weintraub D, Hurtig HI, Duda JE, Xie SX, et al. Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neltner JH, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Denison SK, Anderson S, Patel E, et al. Digital pathology and image analysis for robust high-throughput quantitative assessment of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:1075–85. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182768de4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferman T, Boeve B, Smith G, Lin S, Silber M, Pedraza O, et al. RBD improves the diagnostic classification of dementia with lewy bodies. Neurology. 2011 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:661–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Lin SC, Bieniek K, et al. Validation of the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in an aging and dementia cohort. Sleep Med. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC, Knopman D, et al. DLB fluctuations: specific features that reliably differentiate DLB from AD and normal aging. Neurology. 2004;62:181–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahn S, Elton RL . UPDRS Development committee. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, Goldstein M, editors. Recent developments in Parkinson’s disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987. pp. 153–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray ME, Lowe VJ, Graff-Radford NR, Liesinger AM, Cannon A, Przybelski SA, et al. Clinicopathologic and 11C-Pittsburgh compound B implications of Thal amyloid phase across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Brain. 2015;138:1370–81. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beach TG, White CL, Hamilton RL, Duda JE, Iwatsubo T, Dickson DW, et al. Evaluation of alpha-synuclein immunohistochemical methods used by invited experts. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:277–88. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujishiro H, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti RJ, et al. Validation of the neuropathologic criteria of the third consortium for dementia with Lewy bodies for prospectively diagnosed cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:649–56. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817d7a1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janocko NJ, Brodersen KA, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Ross OA, Liesinger AM, Duara R, et al. Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease differ significantly from neurofibrillary tangle-predominant dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:681–92. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1044-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray-Mukherjee J, Nimon K, Mukherjee S, Morris DW, Slotow R, Hamer M. Using commonality analysis in multiple regressions: a tool to decompose regression effects in the face of multicollinearity. Methods Ecol Evol. 2014;5:320–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lashley T, Holton JL, Gray E, Kirkham K, O’Sullivan SS, Hilbig A, et al. Cortical alpha-synuclein load is associated with amyloid-beta plaque burden in a subset of Parkinson’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:417–25. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pletnikova O, West N, Lee MK, Rudow GL, Skolasky RL, Dawson TM, et al. Abeta deposition is associated with enhanced cortical alpha-synuclein lesions in Lewy body diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colom-Cadena M, Gelpi E, Charif S, Belbin O, Blesa R, Martí MJ, et al. Confluence of α-synuclein, tau, and β-amyloid pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:1203–12. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iseki E, Marui W, Kosaka K, Uéda K. Frequent coexistence of Lewy bodies and neurofibrillary tangles in the same neurons of patients with diffuse Lewy body disease. Neurosci Lett. 1999;265:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishizawa T, Sahara N, Ishiguro K, Kersh J, McGowan E, Lewis J, et al. Co-localization of glycogen synthase kinase-3 with neurofibrillary tangles and granulovacuolar degeneration in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1057–67. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Sagara Y, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, et al. β-Amyloid peptides enhance α-synuclein accumulation and neuronal deficits in a transgenic mouse model linking Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2001;98:12245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211412398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masuda-Suzukake M, Nonaka T, Hosokawa M, Oikawa T, Arai T, Akiyama H, et al. Prion-like spreading of pathological α-synuclein in brain. Brain. 2013;136:1128–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. Lewy body–like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:504–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J-Y, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, et al. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med. 2008;14:501–3. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luk KC, Kehm VM, Zhang B, O’Brien P, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Intracerebral inoculation of pathological alpha-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative alpha-synucleinopathy in mice. J Exp Med. 2012;209:975–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Recasens A, Dehay B, Bove J, Carballo-Carbajal I, Dovero S, Perez-Villalba A, et al. Lewy body extracts from Parkinson disease brains trigger alpha-synuclein pathology and neurodegeneration in mice and monkeys. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:351–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.24066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badiola N, de Oliveira RM, Herrera F, Guardia-Laguarta C, Goncalves SA, Pera M, et al. Tau enhances alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in cellular models of synucleinopathy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT, et al. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;300:636–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1082324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bachhuber T, Katzmarski N, McCarter JF, Loreth D, Tahirovic S, Kamp F, et al. Inhibition of amyloid-beta plaque formation by alpha-synuclein. Nat Med. 2015;21:802–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo JL, Covell DJ, Daniels JP, Iba M, Stieber A, Zhang B, et al. Distinct α-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell. 2013;154:103–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bousset L, Pieri L, Ruiz-Arlandis G, Gath J, Jensen PH, Habenstein B, et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alpha-synuclein strains. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2575. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peelaerts W, Bousset L, Van der Perren A, Moskalyuk A, Pulizzi R, Giugliano M, et al. alpha-Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature. 2015;522:340–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kotzbauer PT, Cairns NJ, Campbell MC, Willis AW, Racette BA, Tabbal SD, et al. Pathologic accumulation of alpha-synuclein and Abeta in Parkinson disease patients with dementia. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1326–31. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabbagh MN, Adler CH, Lahti TJ, Connor DJ, Vedders L, Peterson LK, et al. Parkinson disease with dementia: comparing patients with and without Alzheimer pathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:295–7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819c5ef4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kempster PA, O’Sullivan SS, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. Relationships between age and late progression of Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study. Brain. 2010;133:1755–62. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider J, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Boyle P, Leurgans S, Bennett D. Cognitive impairment, decline and fluctuations in older community-dwelling subjects with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012;135:3005–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiraboschi P, Attems J, Thomas A, Brown A, Jaros E, Lett DJ, et al. Clinicians’ ability to diagnose dementia with Lewy bodies is not affected by β-amyloid load. Neurology. 2015;84:496–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.