Abstract

In 2012 Oregon transformed its Medicaid program, providing coverage through sixteen coordinated care organizations (CCOs). The state identified the elimination of health disparities as a priority for the CCOs, implementing a multipronged approach that included strategic planning, community health workers, and Regional Health Equity Coalitions. We used claims-based measures of utilization, access, and quality to assess baseline disparities and test for changes over time. Prior to the CCO intervention there were significant white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native disparities in utilization measures and white-black disparities in quality measures. The CCOs’ transformation and implementation of health equity policies was associated with reductions in disparities in primary care visits and white-black differences in access to care, but no change in emergency department use—with higher visit rates persisting among black and American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees, compared to whites. States that encourage payers and systems to prioritize health equity could reduce racial and ethnic disparities for some measures in their Medicaid populations.

Vast and pervasive health care disparities exist for most racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States.1 These disparities are particularly acute among people enrolled in the Medicaid program, which provides a disproportionate amount of insurance coverage for members of racial and ethnic minority groups. States are granted much flexibility in the ways that they structure their Medicaid programs, which creates opportunities to address disparities through payment and delivery system reforms.2 One example of this approach is a suite of reforms undertaken by Oregon, which identified the elimination of health disparities as a top priority for its Medicaid program.

As in other states, Oregon’s measures of health care access, quality, and utilization have been poorer among racial and ethnic minority populations than those of their white counterparts. For example, in 2011 more than 35 percent of minority women in Oregon had no regular care provider, compared to 18 percent of white women, and the life expectancy for Oregonians who were black or American Indian/Alaska Native was two years lower than that for those who were white.3

These observations set the stage as Oregon explicitly identified “Health Equity and Eliminating Health Disparities” as a key goal of its 2012 Medicaid reform. This reform created sixteen coordinated care organizations (CCOs) to provide care for 90 percent of the state’s Medicaid population.4–7 CCOs can be seen as a type of Medicaid accountable care organization (ACO), although they have similarities to managed care organizations—including an administrative layer that serves as an intermediary and contracting agent for the state and providers.7 The scope of CCOs is generally broader than that of most Medicare ACOs and Medicaid managed care organizations, and it includes the coordination of physical, behavioral, and oral health, as well as some of the social service needs of CCO members. Furthermore, accountability is extended to include health equity.

Background

Oregon’s CCOs focused on three main strategies to reduce disparities, based on a conceptual model of improved cultural competency.8–10 These strategies included transformation plans, Regional Health Equity Coalitions, and an expansion of the community health worker workforce.

Transformation Plans

CCOs were required to develop and implement transformation plans that included efforts to reduce disparities for their specific member populations. As a result, CCOs engaged in a variety of activities designed to address gaps in outreach, access, and communication that were related to disparities. These activities included adopting the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care11 to evaluate their organizational capabilities and activities, hiring new staff members dedicated to working on equity, ensuring that the cultural and linguistic needs of their members were met with appropriate workforce diversity and training, and supporting the adoption of cultural competency policies by the CCO’s clinics and providers. CCOs were also encouraged and given support to use data in new ways, analyzing and reporting quality and utilization measures from claims data, stratified by race and ethnicity, to identify disparities for racial and ethnic minority groups.

Regional Health Equity Coalitions

Oregon established Regional Health Equity Coalitions to create backbone agencies for CCOs and communities that were historically underrepresented in health program and policy development. The coalitions provided health equity guidance to CCOs, supporting the representation of culturally and linguistically diverse communities on CCO advisory councils and advocating for the provision of services in neighborhoods where minority members resided. For example, one coalition worked with community members to identify barriers in health care access, leading to a CCO-coalition initiative aimed at improving the use of health care interpretive services. Coalitions also reviewed CCOs’ workforce recruitment and diversity policies and advocated for the inclusion of health equity as an agenda item for meetings of the CCOs’ boards of directors.

Expansion Of Community Health Workers

Oregon invested heavily in community health workers, developing a certification board for traditional health workers (which included community health workers) and certifying more than 400 trained community health workers after the state’s 2012 transformation of its Medicaid program. The state encouraged CCOs to incorporate these workers into their service delivery as a means of enhancing cultural competency and building community capacity.12 Oregon’s community health workers provided a new source of information and outreach, using personal relationships and an understanding of their community to provide a link between the people and their local health care services. These efforts were expected to support the state’s goals of eliminating health disparities.

Other Activities

In addition to the implementation of transformation plans and Regional Health Equity Coalitions, as well as the expansion of the community health worker workforce, the state also engaged in a variety of complementary legislative, policy, and capacity-building activities. These efforts included state-supported leadership training that was committed to advancing health equity and passage of a new law to improve the cultural competence training of health care professionals.

Taken together, these initiatives offer an example of an ambitious but feasible effort by a state to use Medicaid reform as a mechanism to reduce disparities. In this study we sought to more explicitly identify the effects of these reforms on utilization and quality for the two years after implementation. Specifically, we used claims data to focus on two of the most vulnerable minority groups in Oregon Medicaid, examining white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native disparities in health service use and care quality at baseline (2010–11). We then tested for reductions in disparities associated with the suite of policies initiated in 2012.

Study Data And Methods

Study Population

Our population included Oregon residents enrolled in Medicaid during the period January 2010–December 2014. We excluded people with short enrollment periods (less than three months within a twelve-month window), those enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, and those not enrolled in a CCO. We excluded Medicaid enrollees from one CCO that was not launched until August 2013. We also excluded people who were newly enrolled in Medicaid in 2014 as part of the program’s expansion of eligibility under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) because new enrollees were likely to differ significantly in observed and unobserved ways from traditional enrollees, which could have confounded our estimates of the impact of disparities-related policies. We obtained Medicaid enrollment and claims data from the Oregon Health Authority. Enrollment data included self-reported race and Hispanic ethnicity information, which we supplemented with tribal membership records. If a record of tribal membership was available, it superseded race information, and we grouped people with tribal membership together with American Indians/Alaska Natives. After initial study exclusions, we excluded an additional 9 percent of enrollees with missing data on race.

We used Stata, version 15.0, and R, version 3.4.1. The Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University approved this research.

We defined a disparity as a risk-adjusted difference in our outcomes of interest (for example, primary care visits or preventable hospitalizations) between non-Hispanic whites (the reference group) and the following two groups of minority enrollees: non-Hispanic blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives. We focused on black and American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees and excluded Hispanics, Asian Americans, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders from this study. This approach was driven by a review of data in the pre-CCO period, which identified prominent white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native disparities. In contrast, Hispanic, Asian American, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander enrollees had relatively few differences in comparison to white enrollees (see online appendix exhibit 1).13

Study Design

We assessed the impact of Oregon’s Medicaid transformation and efforts to reduce disparities in two steps. First, we computed pre-intervention (2010–11) white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native disparities across five utilization measures and nine quality measures. Then, we selected measures with pre-intervention disparities and used a difference-in-differences approach to assess the impact of Oregon’s efforts to reduce disparities. We used 2010–11 as the pre-intervention period and 2013–14 as the post-intervention period. The year 2012 was treated as a transition year. Furthermore, we conducted subanalyses to assess changes associated with neighborhood racial composition.

Outcome Measures

We assessed disparities across four utilization measures and four quality measures, calculated for each member year. We analyzed utilization outcomes in terms of rates per thousand member months. Our utilization measures included primary care visits, emergency department (ED) visits, potentially avoidable ED visits,14 and other outpatient visits (that is, excluding ED and behavioral health care). Our quality measures focused on direct and indirect measures of access, including access to preventive/ambulatory health services among children ages 1–6 and adults ages 45–64 who had an ambulatory or preventive care visit during the year, defined by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set;7 unplanned thirty-day all-cause readmissions; and measures of preventable hospitalizations for chronic conditions, as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Prevention Quality Indicators.15

Covariates

Statistical analyses adjusted for age; sex; health risk, using the Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System risk indicators;16 and rurality of residence, based on rural-urban commuting area codes.17

Statistical Analysis

We first assessed white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native disparities in health service utilization and quality prior to the CCO intervention (2010–11), using the white population as a reference group. The unit of analysis was the person-year. Statistical models adjusted for age, sex, Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System health risk indicators, and rural-urban residence.

We then focused on measures with an existing disparity and assessed changes in disparities following the CCO transformation using a difference-in-differences model. Each multivariate linear model included a binary indicator for race (white or the minority of interest), an indicator of the post-intervention period (2013–14), and the interaction between race and the post-intervention period, which produced our estimates of the policy effects. Based on their ZIP code of residence, each beneficiary was assigned to one of 130 primary care service areas, which represented natural geographic areas for care delivery.18–21 Standard errors were clustered at the primary care service area level.22

We tested the assumption of parallel trends using a longer series of pre-period data and testing for significance in the interaction of a secular trend and an indicator for black or American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees before 2012.16,17 We also tested the overall sensitivity of our results by restricting the population to people residing in urban areas, to confirm that observed results were not driven by differences in geographic distribution. Finally, we assessed the role of racial composition in the primary care service area in comparisons of primary care and ED visits for black and white enrollees. In these analyses we grouped black enrollees into two groups—those residing in service areas with the greatest concentration of black residents and those in areas with the smallest concentration, with the median value serving as the cutoff.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, we relied on claims data, which are limited in their ability to capture all of an enrollee’s risk factors or to provide a comprehensive assessment of the experience and quality of a care episode.

Second, our observed changes in disparities might not be generalizable to the broader American Indian/Alaska Native community. Unlike most groups, tribal members were not required to enroll in managed care organizations or CCOs, and those who opted to enroll may have been more comfortable with the general health care system than their counterparts who opted not to join CCOs and instead obtain most of their care through the Indian Health Service.

Third, while we assessed changes occurring in the period 2010–14, we could not directly attribute observed reductions in disparities to specific initiatives (transformation plans, Regional Health Equity Coalitions, or expanded use of community health workers) or other aspects of the CCO transformation. CCOs engaged in a wide variety of other delivery system reforms, including increased enrollment in primary care homes and efforts to integrate physical and behavioral health care—efforts that may have indirectly reduced disparities. Some of the observed reductions in disparities may have been related to differential impacts of the Medicaid expansion, rather than a result of specific policies designed to reduce disparities.

Fourth, our selection of measures was based not on a theoretical model or specific targets set by the state, but rather on a review of data on existing disparities prior to the CCO intervention.

Fifth, it is possible that disparities within the Medicaid population could have narrowed, even as overall disparities between the Medicaid and commercial populations grew wider.

Finally, we note that the share of non-Hispanic black enrollees in Oregon’s Medicaid population is substantially smaller than the national average (4 percent in Oregon versus 22 percent nationally).23 Therefore, results from Oregon might not be generalizable to other states.

Study Results

Patient Characteristics

Our study included 601,217 Medicaid enrollees (exhibit 1). Compared to non-Hispanic white enrollees, non-Hispanic black and American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees had similar demographic profiles, although black enrollees were slightly younger and more likely to reside in urban areas.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of Oregon Medicaid enrollees in the study population

| Characteristic | Whites (n = 538,682) | Blacks (n = 36,601) | AI/ANs (n = 25,925) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.6 | 17.9 | 20.0 |

| Female | 55.5% | 53.6% | 54.7% |

| Neighborhood poverty ratea | 27.3% | 28.8% | 28.2% |

| Urban residence | 80.5% | 96.6% | 75.9% |

| CDPS risk score | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2010–14 Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES AI/AN is American Indian/Alaska Native. CDPS is the Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System, a Medicaid risk adjustment system that uses ICD9 codes to identify a variety of medical conditions and their severity. Higher numbers are associated with populations with more chronic conditions.

Percentage of residents in the enrollee’s primary care service area with incomes below 150 percent of the federal poverty level.

Pre-intervention Disparities

Disparities in utilization were prevalent in white-black and white–American Indian/Alaska Native comparisons (exhibit 2). Compared to white enrollees, black enrollees had significantly higher ED visit rates (27 percent higher for overall ED visits and 31 percent higher for potentially avoidable ED visits). Black enrollees also had visit rates that were 14 percent lower than those of white enrollees for primary care and 11 percent lower for other outpatient visits. American Indian/Alaska Native–white disparities in utilization were similar to white-black disparities, but smaller in magnitude.

Exhibit 2.

Changes in racial/ethnic disparities for selected measures associated with Oregon’s 2012 implementation of Medicaid coordinated care organizations (CCOs)

| Pre-intervention measures for white enrollees (unadjusted) | White-black or white-AI/AN disparity (adjusted) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention period | Post-intervention period | Change over time | ||

| White-black differences | ||||

| Utilization measures (per 1,000 member months) | ||||

| Primary care visits | 335.7 | −39.8**** | −25.4**** | 14.4**** |

| Other outpatient visitsa | 307.8 | −30.7**** | −17.2**** | 13.5**** |

| ED visits | 64.0 | 15.9**** | 16.0**** | 0.1 |

| Potentially avoidable ED visits, ages 18 and older | 13.9 | 4.0**** | 3.5**** | −0.5 |

| Quality measures | ||||

| Access to preventive/ambulatory services, ages 45–64b | 89.0% | −2.5%*** | −0.4% | 2.1%*** |

| Access to preventive/ambulatory services, ages 1–6b | 86.6% | −2.5%**** | −0.1% | 2.4%**** |

| Unplanned 30-day all-cause readmission rate | 13.6% | 1.8% | —c | —c |

| Preventable hospital admissions for chronic conditionsd | 2,086.1 | 1,858.9**** | 1,183.1**** | −675.7 |

| White–American Indian/Alaska Native differences | ||||

| Utilization measures (per 1,000 member months) | ||||

| Primary care visits | 335.7 | −15.2**** | −2.9 | 12.2**** |

| Other outpatient visitsa | 307.8 | −9.2**** | −2.6 | 6.6** |

| ED visits | 64.0 | 6.0**** | 4.8**** | −1.2 |

| Potentially avoidable ED visits, ages 18 and older | 13.9 | 1.6** | 0.9** | −0.7 |

| Quality measures | ||||

| Access to preventive/ambulatory services, ages 45–64b | 89.0% | −1.0% | —c | —c |

| Access to preventive/ambulatory services, ages 1–6b | 86.6% | −0.9% | —c | —c |

| Unplanned 30-day all-cause readmission rate | 13.6% | 3.1%** | 1.1% | −2.0% |

| Preventable hospital admissions for chronic conditionsd | 2,086.1 | 570.2 | —c | —c |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2010–14 Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES The pre-intervention period is 2010–11. The post-intervention period is 2013–14. Changes over time are the changes for black or American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) enrollees compared to white enrollees. Adjusted estimates adjust for age, sex, Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System risk indicators, and rurality of residence.

Excluding emergency department (ED) and behavioral health care.

Not applicable (no baseline disparity).

Per 100,000 member years. These admissions include those for diabetes (with short-term complications, with long-term complications, with lower-extremity amputation, or uncontrolled without complications), or for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, hypertension, heart failure, or angina without a cardiac procedure.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Among our four quality measures, patterns in disparities were not as consistent. Compared to white enrollees, black enrollees had lower quality scores in three measures (access to preventive/ambulatory services by adults ages 45–64, access to those services by children ages 1–6, and preventable hospitalizations for chronic conditions). Relative to whites, American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees had similar quality measures, with the exception of the all-cause readmission rate measure.

Changes In Disparities Associated With Oregon’s Medicaid Transformation

Following Oregon’s Medicaid transformation and the introduction of health equity policies, white-black disparities in primary care visits and outpatient visits narrowed significantly. For example, the white-black difference in primary care visits was reduced by 14.4 visits per 1,000 member months, representing a 36 percent reduction in the pre-intervention disparity (exhibit 2). There were no significant changes in overall ED visits or potentially avoidable ED visits. Similar patterns were observed among American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees, with gaps in primary care visits and outpatient visits decreasing and no significant change in ED visits. Pre-intervention trends were parallel across all outcomes, with the following exception: outpatient visits in the white-black analysis (for results of these analyses, see appendix exhibit 2).13. Sensitivity analyses that addressed differences in the pre-intervention trends for outpatient visits produced results that were consistent with results shown in exhibit 2 but suggested that the effect may have been moderated and was potentially attributable to factors that predated the CCO intervention.

White-black disparities also narrowed for measures of access (access to preventive/ambulatory services for both age groups discussed above). The relative reductions in readmission rates for American Indian/Alaskan Native enrollees and preventable admissions for chronic conditions for black enrollees were not significant, although the change in preventable admissions was large in magnitude (675.7 visits per 100,000 member years).

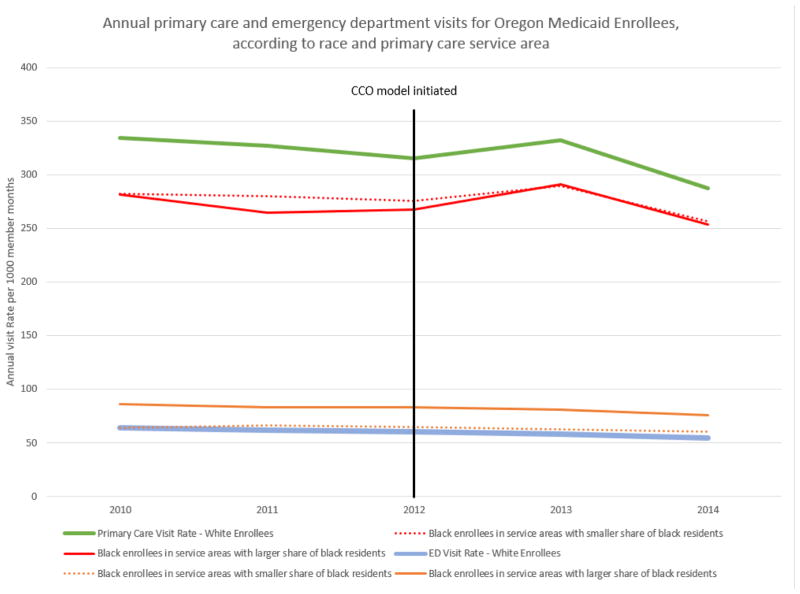

Differences In White-Black Disparities In Primary Care And Emergency Department Visit Rates By Service Area

Prior to the CCO intervention, average unadjusted primary care visits were lower for black enrollees in primary care service areas with a higher concentration of black residents relative to those in areas with a lower share. However, these visit rates converged with the introduction of the CCO model (exhibit 3; adjusted analyses are provided in appendix exhibit 3).13 Across all groups, numbers of primary care visits increased substantially in 2013 and dropped in 2014—which may reflect efforts to improve access by CCOs in 2013, followed by challenges related to primary care capacity resulting from the 2014 Medicaid expansion. Exhibit 3 displays a gradual decline in ED visits across all groups, with no change in black versus white enrollees. In contrast to primary care visits, the disparity in ED visits was present primarily in people living in areas with greater shares of black residents.

Exhibit 3.

Annual primary care and emergency department (ED) visits for Oregon Medicaid enrollees in 2010–14, overall for whites and by primary care service area type for blacks

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2010–14 Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES Black enrollees were divided into two categories: those living in primary care service areas with a share of black residents above the median (higher black share area), and those living in areas with a share of black residents below the median (lower black share area). In 2012 Oregon transformed its Medicaid program, providing coverage through sixteen coordinated care organizations (CCOs).

Discussion

Medicaid offers a potential mechanism to address disparities, both in the expansions possible through the ACA24–28 and through delivery reforms within state programs. Oregon’s Medicaid transformation is an example of the latter. In this study we found Oregon’s model to be associated with reductions in disparities in primary care use and in the narrowing of white-black gaps in measures of access to care. Observed changes were most substantial among black enrollees, who experienced a 36 percent reduction in the pre-intervention disparity in primary care visits. We observed no changes in disparities in overall or avoidable ED visits among black or American Indian/Alaska Native enrollees. White-black disparities in the rate of preventive hospitalizations decreased, indicating a trend in the desired direction, but the change was not significant.

The reduction in the white-black disparity in primary care visits was largest in areas with higher percentages of black residents, but these changes did not translate into lower ED visits among these groups. These findings are suggestive of efforts that may have targeted local neighborhoods with existing disparities, but they also suggest that reductions in ED visits might not be tied directly to increased primary care use, at least in these populations. Furthermore, the majority of black Medicaid beneficiaries were located in the Portland and Salem metropolitan areas. Although our results were qualitatively similar when we restricted our analysis to urban areas, the change in white-black disparities may be primarily attributable to the two or three CCOs located in urban areas and might not be generalizable to all of the CCOs.

Our results suggest that Oregon’s prioritization of disparities as a key target for Medicaid reform may have had some early successes. In particular, the use of data to measure and identify disparities may have allowed CCOs to target key areas on which to focus. Overall, each part of Oregon’s multipronged approach—using transformation plans to set strategic goals and implement change, coordinating with Regional Health Equity Coalitions, and expanding the use of community health workers—was likely to raise the awareness of the existence of disparities in general and encourage actions to address specific health inequities within a CCO.

One somewhat surprising result of our assessment of differences prior to the CCO intervention was the lack of more prominent disparities among the Hispanic and Asian populations(appendix Exhibit 1. Baseline Assessments of Disparities Across All Racial & Ethnic Groups13) However, claims data provide a coarse approximation of patient outcomes, health, and experiences. It is possible that efforts to improve cultural competencies in Oregon may have detected and addressed disparities among Hispanic and Asian American/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander enrollees in ways that were not easily observed in claims data. Furthermore, our findings of observed reductions in disparities, while sizable in some measures, might not necessarily translate to reduced disparities in clinical measures or the patient experience. In addition, Medicaid expansion may reduce some disparities while exacerbating others. For example, increases in enrollment could differentially crowd out or constrain access to care for some racial and ethnic minority groups.

Oregon plans to continue to use its CCO model to address disparities. A recent state-contracted assessment of Oregon’s progress in reducing disparities29 noted progress in CCOs’ activities in reviewing and improving their own workforce recruitment and diversity policies, procedures, and practices; supporting workforce diversity in their clinics and provider groups; and providing staff training on cultural competency, cultural diversity, and health equity. The report also noted that despite the breadth of activities, relatively few were coordinated across the state or conducted in a systematic way with specific, defined goals.

As part of their 2015–17 contracts with the Oregon Health Authority, CCOs renewed their commitment to reducing disparities by explicitly agreeing to ensure that communications and outreach would be tailored to cultural and linguistic needs, that diverse needs of members would be met through cultural competency training, and that provider composition would reflect member diversity. They also agreed to develop a quality improvement plan that would include incentive measures to reward efforts to reduce disparities.29 Notably, the latter part of this effort has been more elusive. Quality metrics for reducing disparities have been intrinsically more complicated than standard quality metrics, since disparities reflect performance relative to other groups.30 An important task for Oregon and other states will be to identify the best metrics to use in monitoring and incentivizing efforts to reduce disparities.

Conclusion

Given the size of the program and the populations it covers, Medicaid offers a significant opportunity to address long-standing health disparities in the United States. Oregon’s approach—prioritizing health equity through transformation plans, regional health equity coalitions, and a robust community health worker workforce—shows signs of early successes and may serve as a model for other states. Expanding the reach of successful models and adopting programs to reflect local context could address the country’s persistent disparities in health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for all authors was provided by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grant No. 1R01MD011212).

Contributor Information

K. John McConnell, Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine and director of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, both at Oregon Health & Science University, in Portland.

Christina J. Charlesworth, Research associate at the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, Oregon Health & Science University

Thomas H. A. Meath, Research associate at the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, Oregon Health & Science University

Rani Mary George, Research project manager at the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, Oregon Health & Science University.

Hyunjee Kim, Research assistant professor at the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness and in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

NOTES

- 1.Smedley BR, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb LM, Quiñones-Rivera A, Manchanda R, Wing H, Ackerman S. States’ influences on Medicaid investments to address patients’ social needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Health Care Innovation Plan [Internet] Salem (OR): The Authority; 2012. [cited 2018 Jan ??]. Available from: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/OHPB/healthreform/docs/or-heath-care-innovation-plan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnell KJ. Oregon’s Medicaid coordinated care organizations. JAMA. 2016;315(9):869–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Lindrooth RC, Cohen DJ, Wallace NT, Chernew ME. Oregon’s Medicaid reform and transition to global budgets were associated with reductions in expenditures. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(3):451–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Chan BK, Meath TH, Mendelson A, Cohen D, et al. Early performance in Medicaid accountable care organizations: a comparison of Oregon and Colorado. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):538–45. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McConnell KJ, Chang AM, Cohen DJ, Wallace N, Chernew ME, Kautz G, et al. Oregon’s Medicaid transformation: an innovative approach to holding a health system accountable for spending growth. Healthc (Amst) 2014;2(3):163–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(4, Suppl 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O., 2nd Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3, Suppl):68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh HK, Gracia JN, Alvarez ME. Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services—advancing health with CLAS. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):198–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1404321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):247–59. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 14.Medi-Cal Managed Care Division. Statewide Collaborative Quality Improvement Project: reducing avoidable emergency room visits: final remeasurement report: January 1, 2010–December 31, 2010 [Internet] Sacramento (CA): California Department of Health Care Services; 2012. Jun, [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/reports/Documents/MMCD_Qual_Rpts/EQRO_QIPs/CA2011-12_QIP_Coll_ER_Remeasure_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prevention Quality Indicators overview [Internet] Rockville (MD): AHRQ; [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/pqi_overview.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronick R, Gilmer T, Dreyfus T, Lee L. Improving health-based payment for Medicaid beneficiaries: CDPS. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(3):29–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart G. Rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes (version 2.0) 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman DC, Mick SS, Bott D, Stukel T, Chang CH, Marth N, et al. Primary care service areas: a new tool for the evaluation of primary care services. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(1 Pt 1):287–309. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dartmouth Institute. Primary Care Service Area (PCSA) [Internet] Lebanon (NH): Dartmouth Institute; 2015. [cited 2018 Jan ??]. Available from: http://tdi.dartmouth.edu/research/evaluating/health-system-focus/primary-care-service-area. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oregon Office of Rural Health. Definition of service area [Internet] Portland (OR): Oregon Health and Science University; [cited 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/outreach/oregon-rural-health/data/rural-definitions/service-area.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlesworth CJ, Meath TH, Schwartz AL, McConnell KJ. Comparison of low-value care in Medicaid vs commercially insured populations. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):998–1004. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119(1):249–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid enrollment by race/ethnicity: FY2013 [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): KFF; c2018. [cited 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-enrollment-by-raceethnicity/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes SL, Riley P, Radley D, McCarthy D. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in access to care: has the Affordable Care Act made a difference? [Internet] New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2017. Aug, [cited 2018 Jan 25]. (Issue Brief). Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2017/aug/hayes_racial_ethnic_disparities_after_aca_ib.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ndumele CD, Mor V, Allen S, Burgess JF, Jr, Trivedi AN. Effect of expansions in state Medicaid eligibility on access to care and the use of emergency department services for adult Medicaid enrollees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):920–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berenson J, Li Y, Lynch J, Pagán JA. Identifying policy levers and opportunities for action across states to achieve health equity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(6):1048–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole MB, Galárraga O, Wilson IB, Wright B, Trivedi AN. At federally funded health centers, Medicaid expansion was associated with improved quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(1):40–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han X, Luo Q, Ku L. Medicaid expansion and grant funding increases helped improve community health center capacity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(1):49–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bau I. Opportunities for Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations to advance health equity [Internet] Salem (OR): Oregon Health Authority; 2017. Jun, [cited 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/CSI-TC/Documents/CCO-Opportunities-to-Advance-Health-Equity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blustein J, Weissman JS, Ryan AM, Doran T, Hasnain-Wynia R. Analysis raises questions on whether pay-for-performance in Medicaid can efficiently reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(6):1165–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.