Abstract

Background & Aims

Subepithelial fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can be detected only in esophageal biopsies with adequate amounts of lamina propria (LP). We investigated how often pediatric esophageal biopsies contain adequate LP, and whether esophageal eosinophilia influences the acquisition rates.

Methods

We evaluated 284 esophageal biopsy specimens from 39 EoE patients, and 87 biopsy specimens from 32 patients without esophageal eosinophilia or other esophageal abnormalities for the presence of adequate LP and fibrosis.

Results

On a per-biopsy basis, there was no significant difference in the rate of procuring adequate amounts of LP between EoE patients and patients without esophageal eosinophilia (43% vs 31%, p=0.14). The majority of EoE patients (85%) had fibrosis. Fibrosis in EoE patients was patchy, and more likely to be detected in the middle or distal esophagus (OR 19.93; 95% CI, 4.12–91.52). Among patients with fibrosis, the probability of its detection reached >95% with 7 middle-distal esophageal biopsies. Most children with newly diagnosed EoE already had subepithelial fibrosis despite exhibiting only inflammatory endoscopic features.

Conclusions

Most individual esophageal biopsies in children are inadequate for assessing subepithelial fibrosis, and the rates of procuring adequate LP per biopsy are similar in patients with and without EoE. To reliably detect fibrosis in EoE patients, at least 7 biopsy specimens should be taken from middle-distal esophagus. The finding of fibrosis in children with newly diagnosed EoE and only inflammatory endoscopic features suggests that fibrosis can occur early in this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an antigen-mediated esophageal disease in which esophageal mucosal biopsies reveal an eosinophil-predominant inflammation.1 With chronic eosinophilic inflammation, esophageal fibrosis and remodeling develop and underlie the serious adverse events of EoE.2–5 In adults, the signs of EoE remodeling can be quite obvious with fibrostenotic features such as rings and strictures that cause food impactions.6, 7 In children, who often lack these obvious fibrostenotic features, assessing for early evidence of esophageal remodeling can be challenging.

Endoscopic pinch biopsy specimens reliably sample the esophageal epithelium, but remodeling takes place in the deeper, subepithelial layers of the esophagus that might be beyond the reach of standard endoscopic biopsy techniques. Fibrosis within the lamina propria (LP) is evidence of remodeling, and LP can be included in standard endoscopic esophageal biopsy specimens. However, those specimens often contain only esophageal epithelium either with no associated LP or with LP in quantities insufficient for assessment of subepithelial fibrosis. Indeed, insufficient LP in esophageal biopsies has limited a number of studies that have attempted to evaluate fibrosis in children with EoE.8–14

Criteria that have been used to define “adequate” LP in esophageal biopsy specimens are quite variable, and research in this area would benefit considerably from consensus among investigators on these criteria.12–15 The mere presence of LP does not guarantee adequacy for assessing fibrosis, because crush artifact is common, and it can render biopsy specimens uninterpretable in this regard. Studies that have assessed LP fibrosis in EoE biopsy specimens have found that fibrosis is strongly associated with epithelial eosinophilic inflammation, and the authors of one report speculated that, in EoE esophageal biopsies that have no associated LP, the absence of epithelial eosinophilic inflammation implies that the esophagus is not fibrotic.14 The validity of this assumption has not been established, however, and it is not even clear how often LP is included in esophageal biopsies taken from patients without esophageal eosinophilia.

Few studies have focused specifically on the presence and adequacy of LP in esophageal biopsies, with the exception of some studies on post-ablation surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus (in whom detection of subsquamous intestinal metaplasia requires adequate LP).16 We hypothesized that the frequency of obtaining esophageal biopsy specimens with LP adequate for fibrosis evaluation would be higher in patients with EoE than in those without esophageal eosinophilia. The aim of this study was to determine how often esophageal biopsies taken from pediatric patients with EoE and from those without esophageal eosinophilia contain LP adequate for fibrosis evaluation.

METHODS

Study Subjects

We retrospectively identified and reviewed 39 patients with EoE and 32 patients without esophageal eosinophilia who underwent endoscopic evaluation with biopsies by pediatric gastroenterologists from January to May 2013 at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Tex. Subjects with EoE had ≥15 intraepithelial eosinophils per high-power field (HPF) at any level of the esophagus and did not respond symptomatically and/or histologically to ≥8 weeks of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy as according to 2011 consensus recommendations.1 Subjects without esophageal eosinophilia had normal esophageal histology, no intraepithelial eosinophils, and no endoscopic features of EoE (ie, edema, rings, exudates, furrows, stricture, mucosal fragility, and narrow-caliber esophagus). The study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board. (Supplemental Methods)

Histology

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained esophageal biopsies sectioned at 4 μm thickness were reviewed by two subspecialty-trained pediatric gastrointestinal pathologists (JW and JP). A BX41 microscope with a UPlanFL N 40x/0.75 objective lens with a FN22 eyepiece was used (Olympus America, Center Valley, Pa); the calculated area per high power field (HPF) was 0.237 mm2. For each level of the esophagus, the number of tissue pieces submitted for histologic processing and the number of fragments visualized on the histologic sections were noted. Peak eosinophil counts in the squamous epithelium were determined by counting the number of eosinophils in the HPF with the greatest density of eosinophils. For each fragment, any area of LP without crush artifact was required to be considered adequate for the evaluation of fibrosis. Crush artifact is the result of cell destruction by compression of the biopsy tissue and can be identified as chromatin that is extruded from a damaged nucleus (Supplemental Figure 1). Crushed cells appear as ill-defined collections or streams of darkly basophilic nuclear material without an apparent nuclear membrane. Fragments that had no LP or completely crushed LP were deemed insufficient. Fragments with adequate LP were then evaluated for fibrosis (i.e. absent vs. present). Fibrosis was defined as any amount of thick, brightly eosinophilic collagen bundles that frequently resulted in compression and elongation of intervening intact fibroblast nuclei. The location (ie, proximal, middle, or distal esophagus) of each fragment and the total number of fragments overall were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

For the purpose of our analysis, we considered a fragment identified on a histologic section to be a single biopsy. Data were collated and analyzed using statistical software package GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). p<0.05 was considered statistically significant (Supplemental Methods).

RESULTS

Study Patient Characteristics

We identified 39 patients with EoE at our center who exhibited typical demographic and clinical characteristics of the EoE population with a predominance in males and higher prevalence of atopic disorders such as asthma, eczema, food allergy, or drug allergy compared to 32 patients without esophageal eosinophilia (Table 1). The EoE patients demonstrated clinical symptoms of esophageal dysfunction including dysphagia, food impaction, and heartburn, which were not observed in patients without esophageal eosinophilia. Furthermore, a significant proportion (59%) of EoE patients were already on some therapy to treat the esophageal eosinophilia including PPIs, topical or systemic steroid therapy, and/or dietary therapy compared to patients without esophageal eosinophilia. Nevertheless, about 1/3 of patients without esophageal eosinophilia were also taking PPIs.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis N = 39 |

Patients without Esophageal Eosinophilia (normal esophagus) N = 32 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 9.07 (1.6 – 17.8) | 9.8 (0.6 – 17.6) | 0.58 |

| Males | 27 (69%) | 13 (41%) | 0.02 |

| White | 23 (59%) | 28 (88%) | <0.01 |

| Atopy‡ | 35 (90%) | 14 (44%) | <0.01 |

| On therapy§ | 23 (59%) | 11 (34%) | 0.04 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Dysphagia | 16 (41%) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Food impaction | 3 (8%) | 0 | 0.25 |

| Heartburn or chest pain | 9 (23%) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (44%) | 25 (78%) | <0.01 |

| Vomiting | 23 (59%) | 6 (19%) | <0.01 |

| Feeding difficulty | 6 (15%) | 1 (3%) | 0.12 |

| Poor weight gain, weight loss, or failure to thrive | 8 (21%) | 7 (22%) | 0.89 |

Patients with asthma, eczema, food allergy, or drug allergy were classified as atopy.

On PPI, topical steroid, systemic steroid, and/or dietary therapy.

Rates of Obtaining Adequate Lamina Propria for Fibrosis Evaluation Were Similar in Biopsies from Pediatric Patients With and Without Esophageal Eosinophilia

Overall, a total of 371 esophageal biopsies were evaluated (284 from EoE patients and 87 from patients without esophageal eosinophilia), and overall only 155 (42%) biopsies demonstrated adequate LP for the evaluation of fibrosis. Because therapies such as PPIs, steroids, and elimination or elemental diets can influence esophageal histology, we compared the rates of obtaining adequate LP in patients that were not on any of these therapies (Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). Patients with EoE were significantly more likely to have had some biopsies with adequate LP (ie, they had ≥1 biopsies demonstrating adequate LP) than patients without esophageal eosinophilia (94% vs 48%, p<0.01). However, our endoscopists took a significantly greater number of biopsies from patients with EoE than from patients without esophageal eosinophilia (7.4 ± 2.4 vs 2.5 ± 1.2 biopsies/patient, p<0.01). When evaluated on a per-biopsy basis, adequate LP procurement rates were similar in EoE patients and patients without esophageal eosinophilia (43% vs 31%, p=0.14).

Table 2.

Biopsy Characteristics of Patients Not on Therapy

| Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis N = 16 |

Patients without Esophageal Eosinophilia (normal esophagus) N = 21 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of biopsies | 119 | 52 | |

| Number of biopsies per patient, mean ± SD | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Biopsies with adequate lamina propria | 51 (43%) | 16 (31%) | 0.14 |

| Patients with adequate lamina propria | 15 (94%) | 10 (48%) | <0.01 |

| Patients with insufficient lamina propria (i.e. Indeterminate) | 1 (6%) | 11 (52%) |

Subepithelial Fibrosis Was Patchy

We examined all biopsies with adequate LP for the presence of fibrosis, and we observed subepithelial fibrosis only in patients with EoE (Supplemental Figure 2). Among our 39 patients with EoE, 33 (85%) had fibrosis (ie, they had ≥1 biopsies demonstrating lamina propria fibrosis), 4 (10%) had no fibrosis (ie, they had ≥1 biopsies demonstrating normal LP and no fibrosis), and 2 (5%) were indeterminate due to insufficient LP.

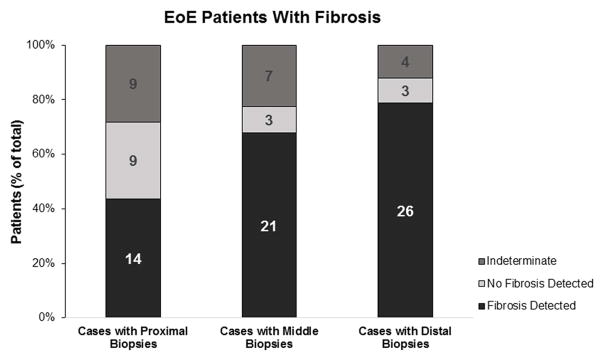

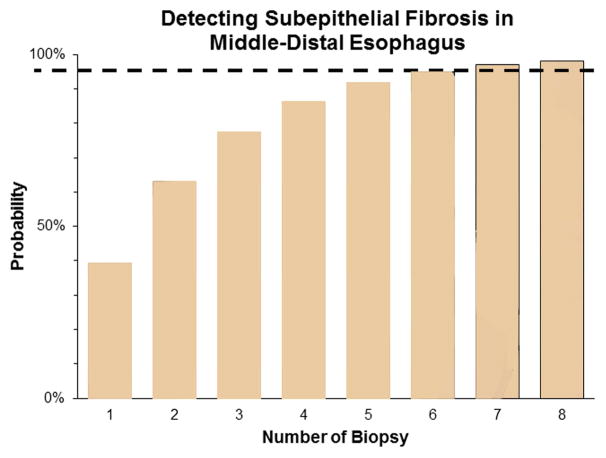

We further examined the 33 EoE patients with fibrosis to determine at what level of the esophagus (ie, proximal, middle, or distal) was the fibrosis detected. The average number of biopsies taken at each level were similar in the proximal, middle, and distal esophagus (2.3 ± 0.9, 2.6 ± 1.1, and 2.9 ± 1.2 biopsies/patient, respectively, p=0.15) The rates of obtaining biopsies with adequate LP were no different in the proximal, middle, or distal esophagus (48%, 46%, and 52%, respectively, p=0.57). Interestingly, we found that LP fibrosis was patchy in distribution (Figure 1a). Biopsies that demonstrated normal LP could be detected in any of the 3 levels, and, in some cases, a single level contained both biopsies with fibrosis and normal LP. Thus, fibrosis was not uniformly distributed along the esophagus. Additionally, the majority of biopsies demonstrating fibrosis were from the middle and distal esophagus. On a per-biopsy basis, middle-distal esophageal biopsies were more likely to demonstrate fibrosis (as opposed to normal LP or insufficient LP) compared with proximal esophageal biopsies (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.04–3.47). Conversely, proximal esophageal biopsies were more likely to demonstrate normal LP (as opposed to fibrosis or insufficient LP) compared with middle-distal esophageal biopsies (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.26–5.18). All 33 EoE patients with fibrosis had biopsy specimens taken from the distal esophagus, and 31 EoE patients with fibrosis had specimens taken from the middle esophagus. At both locations, the majority of patients (79% and 68%, respectively) demonstrated fibrosis (Figure 1b). In contrast, of the 32 EoE patients with fibrosis that had biopsies taken from the proximal esophagus, only 44% demonstrated fibrosis, which is a significantly lower detection rate compared with the middle or distal esophagus (p=0.01). In fact, the odds of detecting fibrosis is much higher when EoE patients have biopsies taken from the middle or distal esophagus (OR, 19.93; 95% CI, 4.12–91.52). These findings suggest that an EoE patient with remodeling will likely demonstrate subepithelial fibrosis in their middle and distal esophagus. Last, we evaluated the number of biopsies required to detect fibrosis in our 33 EoE patients with fibrosis. By taking at least 7 biopsy specimens from the middle-distal esophagus, the probability of detecting fibrosis reached >95% (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Location and number of biopsies for optimal detection of fibrosis. (a) Middle and distal esophageal biopsies from EoE patients demonstrated more fibrosis than proximal esophageal biopsies. (b) Fibrosis was more often detected in patients with middle or distal esophageal biopsies. (c) With each increasing number of biopsies in the middle or distal esophagus, the probability of detecting subepithelial fibrosis increases and reaches >95% (dotted line) at 7 biopsies.

Although there were only 4 EoE patients that demonstrated normal LP and no fibrosis on their biopsies, we did compare clinical and biopsy characteristics to the 33 EoE patients with fibrosis (Table 3). The average number of biopsies taken per patient was statistically greater in EoE patients with fibrosis (7.6±2.3 vs. 5.5±1, p=0.05), suggesting that we may have missed fibrosis in these 4 patients. Nevertheless, EoE patients with fibrosis were more likely to be male and had a greater peak eosinophil count than those without fibrosis. Last, the rates of obtaining adequate LP were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 3.

Characteristics of EoE Patients with and without Fibrosis Detected

| EoE with Fibrosis Detected N = 33 |

EoE with No Fibrosis Detected N = 4 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 9.3 (1.6 – 17.8) | 5.9 (1.6 – 9.7) | 0.24 |

| Males | 26 (79%) | 0 | <0.01 |

| White | 17 (52%) | 4 (100%) | 0.12 |

| Atopy‡ | 29 (88%) | 4 (100%) | 1.00 |

| Peak eosinophil count (eos/HPF), mean ± SD | 70.2 ± 34.0 | 35.3 ± 30.1 | 0.03 |

| Symptom duration in years, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.07 |

| On therapy§ | 21 (64%) | 1 (25%) | 0.28 |

| Total number of biopsies | 251 | 22 | |

| Number of biopsies per patient, mean ± SD | 7.6 ± 2.3 | 5.5 ± 1 | 0.05 |

| Biopsies with adequate lamina propria | 123 (49%) | 10 (45%) | 0.75 |

Patients with asthma, eczema, food allergy, or drug allergy were classified as atopy.

On PPI, topical steroid, systemic steroid, and/or dietary therapy.

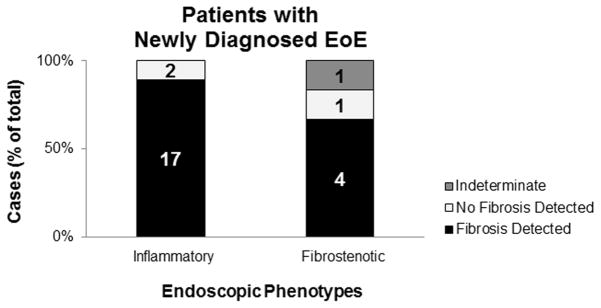

Inflammatory Phenotypes and Newly Diagnosed EoE Cases Demonstrated Subepithelial Fibrosis

We observed subepithelial fibrosis even in patients with only an inflammatory endoscopic phenotype (ie, exudates, furrows and/or edema without rings or strictures), and even in those with newly diagnosed EoE. Thirty-two EoE patients exhibited inflammatory endoscopic phenotypes, and 29 (91%) of them already had evidence of subepithelial fibrosis (Figure 2a). Two patients with fibrostenotic features were Indeterminate due to insufficient LP on their biopsies. One of them had a total of 4 biopsy specimens taken from the middle esophagus. The other patient had a total of 2 biopsies from the proximal esophagus, 1 from the middle esophagus, and 4 from the distal esophagus all with insufficient LP. One patient with fibrostenotic features had specimens that demonstrate normal LP. In this patient, 1 of 2 proximal biopsies and 1 of 2 middle biopsies demonstrated normal LP. The 2 distal biopsies were insufficient. There were no significant differences in patient demographics or peak eosinophil count between patients with an inflammatory phenotype and those with a fibrostenotic phenotype (Table 4). However, patients with fibrostenotic features reported shorter duration of symptoms. Twenty-five patients had newly diagnosed EoE at the time of their endoscopy (Figure 2b). Twenty-one (84%) patients had evidence of subepithelial fibrosis. Of these 21 new cases of EoE with fibrosis, 17 exhibited only inflammatory endoscopic features (ie, no rings or strictures), whereas 4 exhibited rings on their first endoscopy.

Figure 2.

Subepithelial findings in cases with inflammatory and fibrostenotic endoscopic phenotypes. Although an inflammatory endoscopic phenotype was seen in many cases of EoE (A) and even in those that were newly diagnosed EoE (B), the vast majority demonstrated evidence of subepithelial fibrosis on histopathologic evaluation of biopsies.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Inflammatory and Fibrostenotic Phenotypes

| Inflammatory Phenotype N=32 |

Fibrostenotic Phenotype N=7 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 8.3 (1.6 – 17.8) | 12.7 (1.6 – 17.3) | 0.07 |

| Males | 23 (72%) | 4 (57%) | 0.65 |

| White | 18 (56%) | 5 (71%) | 0.68 |

| On therapy§ | 21 (66%) | 2 (29%) | 0.10 |

| Symptom duration in years, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 0.9 ± 1.0 | 0.02 |

| Peak eosinophil count (eos/HPF), mean ± SD | 66.7 ± 35.0 | 59.4 ± 32.9 | 0.55 |

On PPI, topical steroid, systemic steroid, and/or dietary therapy.

DISCUSSION

EoE is a progressive disease, and fibrostenotic adverse events are expected to arise if the disease and inflammation are not adequately controlled.2, 17–20 Thus, the evaluation of the esophageal subepithelial tissue is critical. However, examining the subepithelial tissue in the pediatric population has been challenging due to insufficient biopsy samples, limiting the ability to evaluate for fibrosis and remodeling.11–14, 21 In this pediatric study, by examining 371 biopsies from EoE patients and patients without esophageal eosinophilia, we address a number of questions including how often esophageal mucosal pinch biopsies contain LP that was sufficient in size and quality to evaluate for the presence of fibrosis and whether the presence of EoE affects the chances of acquiring adequate LP. We also explored the distribution (esophageal location) of fibrosis in patients with EoE.

Overall, we found that only 42% of the esophageal pinch biopsies contained adequate LP for the evaluation of fibrosis at our center. This rate is substantially lower than that of other recent reports.12–15 Our criteria for adequate LP exclude those biopsies that are completely obscured by crush artifact. Crushing the tissue with the forceps can cause the appearance of cohesive LP fibers without visible interfiber spaces (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, this crush artifact can mimic low grade fibrosis. Therefore, in our routine pathology practice, we deem biopsies as suboptimal for evaluation of fibrosis if the LP appears entirely crushed. Other recent reports do not mention the exclusion of crush artifact.12, 14, 15 Another reason for our low rate of acquiring adequate LP may be due to suboptimal sampling techniques practiced by various endoscopists in our study. A study in children with EoE found that 75% of the biopsy specimens taken by a single gastroenterologist had adequate LP for fibrosis evaluation while excluding crush artifact.13 The endoscopist in that study took specimens in a systematic manner, applying suction perpendicularly to the esophageal mucosa.11 In adults with EoE, a deeper sampling technique has been described, which also involved suctioning with tangentially placed forceps yielding subepithelial tissue 55% to 97% of the time.15 Our study examined biopsies at a pediatric center with 17 different attending pediatric gastroenterologists and 6 pediatric gastroenterology fellows performing endoscopy on their patients. Thus, the endoscopic sampling techniques were highly variable, but likely representative of a general pediatric GI practice. Finally, perhaps the biopsy forceps used at our center may be suboptimal for subepithelial tissue sampling. The study by Bussmann et al, compared the efficacy of various biopsy forceps for deep esophageal sampling by examining the yield of subepithelial tissue in adults with EoE.15 They found that large-capacity Radial Jaw 4 were the worst, yielding subepithelial tissue 55% of the time. On the other hand, static jaw forceps FB-11K-1 and FB-45Q-1 (Olympus) were the best, yielding subepithelial tissue 97% and 93% of the time, respectively. In our pediatric center, we routinely use standard capacity single-use Radial Jaw 4 forceps without the needle (Boston Scientific). Large-capacity forceps are not routinely used for sampling the esophagus of pediatric patients.

We also explored whether eosinophilic inflammation influenced the rate of procurement of LP. We had hypothesized that eosinophilic inflammation might alter the esophageal tissue in such a way as to increase the likelihood of procuring LP in biopsies. Although we did find that patients with EoE were more likely to have adequate LP sampled than patients without esophageal disease, the validity of this finding was suspect because of disparities between the groups in esophageal biopsy sampling practices by the endoscopists. Our endoscopists took considerably more biopsies (and probably at more esophageal levels) from the EoE patients, probably due to high suspicion for or prior diagnosis of EoE or the presence of other esophageal abnormalities. To adjust for this difference in clinical practice, we examined the procurement rate of adequate LP on a per-biopsy basis, and we found that this rate was similar for the two groups. Although a recent retrospective study of pediatric patients with EoE observed that the presence of LP was associated with higher levels of tissue eosinophilia, that study did not compare the ascertainment of LP in patients without esophageal eosinophilia.14 Our study, which to our knowledge is the first to examine LP procurement in pediatric patients with a normal esophagus, suggests that the presence of esophageal eosinophilia is not associated with a higher rate of LP procurement. A prospective study involving a standardized biopsy protocol in the two groups would be needed to address this limitation of our study.

Our study is the first to suggest that subepithelial fibrosis may have a patchy distribution in pediatric EoE, with fibrosis more likely to be found in the middle-distal portion of the esophagus. In some cases, we detected fibrosis only at one level of the esophagus, with other levels of the same esophagus showing no fibrosis. In other cases, some biopsies showed LP fibrosis, whereas others taken at the same esophageal level did not. To assess where in the esophagus is fibrosis most likely to be detected, we performed both per-biopsy and per-patient analyses. Overall, there were no differences in number of biopsies taken or biopsies with adequate LP per level to account for differences in fibrosis detection among the esophageal levels. On a per-biopsy analysis, we found that middle-distal esophageal biopsies were more likely to have fibrosis and proximal esophageal biopsies were more likely to have normal LP. These findings suggest that the middle-distal portion of the esophagus might be more prone to fibrogenesis. Moreover, taking biopsy specimens from the middle or distal esophagus increases the odds of detecting fibrosis. With the binomial distribution of the biopsy results, we determined that at least 7 specimens should be taken from the middle or distal esophagus to optimally detect fibrosis in patients with EoE. However, this is likely a conservative estimate because we based this estimate on fragments, and the average number of fragments was slightly more than the average number of tissue pieces per level submitted for histology (2.3 ± 1.0 fragments vs 2.0 ± 0.8 tissue pieces, p<0.01). This difference might be due to a breakage of the tissue during histologic processing or tissue orientation during sectioning.

We identified 4 EoE patients who had adequate LP without fibrosis on their biopsies. Although it is possible that these patients could truly not have fibrosis, it is also possible that fibrosis was just missed because of inadequate biopsy sampling (<7 biopsy specimens taken from the middle-distal esophagus). The same argument can be made for the control patients with normal esophagus. This point, and the small sample size, should be taken into consideration when comparing EoE patients with fibrosis to those 4 EoE patients without fibrosis. Nevertheless, we found that EoE patients with fibrosis were predominantly males and had higher esophageal epithelial eosinophil numbers. Studies by Collins et al and Rajan et al scored LP fibrosis in pediatric EoE cases and found that fibrosis severity positively correlated to the degree of epithelial eosinophilia.12, 14 Thus, our observations are in agreement with these earlier studies and suggest that epithelial inflammation drives fibrogenesis in the LP in the early stages of EoE. Because fibrosis is an excessive deposition of connective tissue with densely packed collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins, one may postulate that the presence of subepithelial fibrosis might allow the LP to adhere to the epithelium, thereby enhancing the acquisition of LP. However, we did not observe a difference in LP acquisition between the two groups.

Similar to other pediatric EoE studies, we observed subepithelial fibrosis in our pediatric EoE patients suggesting that fibrogenesis may be an early feature.12–14 Despite having only inflammatory endoscopic features, the majority of newly diagnosed EoE patients at our center already had evidence of subepithelial fibrosis. There were 3 fibrostenotic cases in which biopsies failed to demonstrate subepithelial fibrosis. Perhaps, not enough biopsies were taken from the middle-distal esophagus to detect the subepithelial fibrosis. However, fibrostenotic features might not entirely be due to subepithelial fibrosis. Instead, fibrostenotic features might involve remodeling in deeper layers of the esophagus not accessible by mucosal pinch biopsies.

Rajan et al. suggested that the absence of procuring lamina propria in an EoE esophageal biopsy in the setting of low or no tissue eosinophilic inflammation would indicate a non-fibrotic esophagus.14 However, our new findings would caution against accepting that assumption. We found that the ability to obtain adequate lamina propria with a pinch biopsy does not seem to be influenced by the presence of eosinophilic epithelial inflammation. Rather, optimizing sampling practice techniques and the selection of biopsy forceps are more likely to enhance LP procurement. Because our retrospective study was limited by differences between the groups in the number of esophageal biopsy specimens taken, we performed a per-biopsy analysis to minimize this bias. However, further prospective studies with standardized biopsy sampling protocols are needed to confirm our results and establish future practice guidelines. Based on our findings, we recommend taking at least 7 esophageal biopsy specimens from the middle-distal esophagus to enhance the yield of obtaining adequate LP to evaluate for fibrosis. Furthermore, our study in pediatric EoE patients supports the findings of other investigations suggesting that fibrosis can occur early in this disease, and that the endoscopic finding of only inflammatory features (without fibrostenotic features) does not reliably exclude the presence of esophageal remodeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported K08-DK099383 (EC), NASPGHAN Foundation/AstraZeneca Award (EC), and AGA Research Scholar Award (EC).

Abbreviations/Acronyms

- EGID

eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- Eos

eosinophils

- GERD

gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- HPF

high power field

- LP

lamina propria

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- PPI-REE

proton pump inhibitor responsive esophageal eosinophilia

Footnotes

Specific author contributions:

Jason Wang: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Jason Y Park: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Rong Huang: statistical analysis and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Rhonda F Souza: drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Stuart J Spechler: drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Edaire Cheng: obtained funding; administrative, technical, or material support; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; statistical analysis; study supervision; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jason Wang, Department of Pathology, Children’s Health Children’s Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, United States

Jason Y. Park, Department of Pathology, Children’s Health Children’s Medical Center, Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, United States

Rong Huang, Department of Research Administration, Children’s Health Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, United States.

Rhonda F. Souza, Center for Esophageal Diseases, Baylor University Medical Center and Center for Esophageal Research, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, Texas

Stuart J. Spechler, Center for Esophageal Diseases, Baylor University Medical Center and Center for Esophageal Research, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, Texas

Edaire Cheng, Departments of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine, Children’s Health Children’s Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, United States

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:577–85. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aceves SS. Tissue remodeling in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: what lies beneath the surface? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1047–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aceves SS. Remodeling and fibrosis in chronic eosinophil inflammation. Dig Dis. 2014;32:15–21. doi: 10.1159/000357004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano I, Aceves SS. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:297–316. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:598–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65:109–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li-Kim-Moy JP, Tobias V, Day AS, et al. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis and hyalinization are features of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:147–53. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ef37a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman JA, Morotti RA, Konstantinou GN, et al. Dietary therapy can reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a historical cohort. Allergy. 2012;67:1299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, et al. Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis Esophagus. 2016 doi: 10.1111/dote.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreae DA, Hanna MG, Magid MS, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Propionate Is an Effective Long-Term Maintenance Therapy for Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1187–97. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajan J, Newbury RO, Anilkumar A, et al. Long-term assessment of esophageal remodeling in patients with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis treated with topical corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:147–156. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussmann C, Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, et al. Comparison of different biopsy forceps models for tissue sampling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2016;48:1069–1075. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, et al. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipka S, Kumar A, Richter JE. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Other Risk Factors on Eosinophilic Esophagitis Phenotype and Esophageal Diameter. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katzka DA. The ‘skinny’ on eosinophilic esophagitis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82:83–8. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.82gr.14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–6. e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singla MB, Chehade M, Brizuela D, et al. Early Comparison of Inflammatory vs. Fibrostenotic Phenotype in Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Multicenter Longitudinal Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e132. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoepfer AM, Panczak R, Zwahlen M, et al. How do gastroenterologists assess overall activity of eosinophilic esophagitis in adult patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:402–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.