Summary

Background

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the leading cause of post-neonatal infant death in high-income countries. Central respiratory system dysfunction seems to contribute to these deaths. Excitation that drives contraction of skeletal respiratory muscles is controlled by the sodium channel NaV1.4, which is encoded by the gene SCN4A. Variants in NaV1.4 that directly alter skeletal muscle excitability can cause myotonia, periodic paralysis, congenital myopathy, and myasthenic syndrome. SCN4A variants have also been found in infants with life-threatening apnoea and laryngospasm. We therefore hypothesised that rare, functionally disruptive SCN4A variants might be over-represented in infants who died from SIDS.

Methods

We did a case-control study, including two consecutive cohorts that included 278 SIDS cases of European ancestry and 729 ethnically matched controls without a history of cardiovascular, respiratory, or neurological disease. We compared the frequency of rare variants in SCN4A between groups (minor allele frequency <0·00005 in the Exome Aggregation Consortium). We assessed biophysical characterisation of the variant channels using a heterologous expression system.

Findings

Four (1·4%) of the 278 infants in the SIDS cohort had a rare functionally disruptive SCN4A variant compared with none (0%) of 729 ethnically matched controls (p=0·0057).

Interpretation

Rare SCN4A variants that directly alter NaV1.4 function occur in infants who had died from SIDS. These variants are predicted to significantly alter muscle membrane excitability and compromise respiratory and laryngeal function. These findings indicate that dysfunction of muscle sodium channels is a potentially modifiable risk factor in a subset of infant sudden deaths.

Funding

UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, National Institute for Health Research, the British Heart Foundation, Biotronik, Cardiac Risk in the Young, Higher Education Funding Council for England, Dravet Syndrome UK, the Epilepsy Society, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, and the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program.

Introduction

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the unexpected death of a seemingly healthy infant. It is the leading cause of post-neonatal infant death in high-income countries1 and accounts for 2400 deaths per year in the USA alone.2 Incidence varies internationally from approximately 0·1 per 1000 livebirths in Japan and the Netherlands to 0·8 per 1000 in New Zealand.1 Death commonly occurs at 2–4 months of age.2 Although the cause of death is unknown, several intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors have been identified, including prematurity, male sex, prone sleeping position, and bed sharing.1, 3 A failure to rouse and respond appropriately to a life-threatening hypoxic event is considered to be a common final pathway.3, 4, 5

Skeletal muscle channelopathies are inherited neuromuscular disorders caused by variants in ion channel genes with an estimated prevalence around one in 100 000.6 NaV1.4 is a skeletal muscle voltage-gated sodium channel, encoded by the gene SCN4A, that is crucial for the generation of action potentials and excitation of muscle. Gain-of-function variants in NaV1.4 typically cause myotonia or periodic paralysis.7 An infantile myotonic phenotype characterised by severe respiratory compromise has been linked to such gain-of-function variants. Affected infants have brief, recurrent episodes of life-threatening respiratory muscle myotonia causing apnoea, hypoxia, and cyanosis.8, 9, 10, 11 Intensive care and tracheostomy are often required.9 The onset of apnoea can be delayed by up to 10 months after birth, when infants are seemingly healthy (appendix p 3). Two deaths from respiratory complications have been reported.8, 9

Loss-of-function variants in NaV1.4 have been reported in patients with congenital myasthenic syndrome and congenital myopathies.12, 13, 14 These patients had evidence of respiratory compromise including sudden brief attacks of apnoea that required ventilator support.12

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the sudden and unexpected death of an apparently healthy infant. It is the leading cause of post-neonatal infant death in high-income countries. Placing infants to sleep in a prone position is associated with a higher risk of sudden death but unidentified risk factors remain. We searched PubMed for papers published in English up to March 1, 2017, reviewing the cause or risk of SIDS using the terms “sudden infant death”, “SIDS”, “sudden unexpected death in infancy”, and “risk factors”. Multiple risk factors have been proposed on the basis of epidemiological, pathological, and genetic studies that include the notion of a vulnerable infantile period due to immature homoeostatic and autonomic regulatory pathways or genetic variation—eg, cardiac channel gene variants. Respiratory failure is ultimately believed to contribute to death.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this study is the first to consider direct failure of the respiratory muscles due to dysfunction of the skeletal muscle ion channel NaV1.4 in the pathogenesis of SIDS. We compared rare variants in the SCN4A gene, which codes for the NaV1.4 channel, among infants who had died of SIDS with variants from ethnically matched controls. We also studied the functional consequences of rare variants in both cases and controls using a heterologous cell system. Only infants who had died from SIDS carried variants that significantly disrupted channel function.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our data are compatible with the clinical features of SIDS and provides new mechanistic clues to death. Developmental regulation of the sodium channel and respiratory muscle fibre types might affect the risk of SIDS. Future research is required to define this relationship, and our findings should be retested in similar and other ethnic groups. Sodium channel dysfunction found in muscle channelopathies can be treated. Studies should assess whether such treatments could ameliorate the risk of sudden death for infants carrying SCN4A gene variants.

These fatal and life-threatening SCN4A respiratory phenotypes are compatible with the model of SIDS pathogenesis. We hypothesised that rare functionally deleterious SCN4A variants might be over-represented in infants who had died of SIDS.

Methods

Study design and participants

We did a case-control study, comparing infants who had died from SIDS with ethnically matched adult controls. We first utilised a small cohort of UK white European SIDS cases and then replicated our findings in a larger cohort of USA samples. We obtained fully anonymised exome data from all SIDS cases from an international exome sequencing collaboration. The cohort consisted of coroners' cases from the UK and cases referred to coroners, medical examiners, or forensic pathologists from six ethnically and geographically diverse populations in the USA. We defined SIDS as the sudden death of a seemingly healthy infant that remained unexplained despite a thorough investigation of the scene and circumstances of death, a comprehensive post-mortem examination including microbiology and histopathology performed by a pathologist or medical examiner with paediatric training, and a multiprofessional review of the available information.15, 16 The control cohort comprised exome sequencing data from adults of European ancestry without a history of cardiac, neurological, or respiratory phenotypes reported to the same international collaboration as the cases, with no further inclusion or exclusion criteria.

Genetic studies were undertaken on anonymised samples as approved by the National Research Ethics Service—Wandsworth (reference: 10-H0803-73) and the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Whole exome sequencing for both cases and controls was done using 1·5–3 μg of genomic DNA. Samples from the UK were sequenced at King's College London using the Sure Select XT Human All Exon v5 Target Enrichment System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA); samples from the USA were sequenced at the Mayo Clinic with the Sure Select XT Human All Exon + UTR v5 Target Enrichment System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). DNA libraries were prepared according to manufacturer's protocols. 100 base pair paired end sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

Sequencing reads from exome sequencing of cases and controls were aligned to the GRCh37 human reference genome using NovoAlign. Variant calling, multi-sample genotyping, and variant quality recalibration was done with GATK. Coverage across the protein-coding regions of the exome and SCN4A specifically were assessed using the Bedtools package. A set of 3847 common variants located outside of regions of the genome where there is extensive linkage disequilibrium17 were used to estimate relatedness within the study cohort and ethnic ancestry alongside the control group using the King software package.18 Cases and controls that clustered closely with individuals from the Caucasian European population from the 1000 Genomes Project were included in the downstream analysis to compare individuals from the same ethnic genetic background.

Variants identified within the SCN4A locus (chromosome 17: 62015914–62050278) were annotated with their predicted effect on the SCN4A transcript NM_000334.4 (GenBank) and allele frequencies derived from the Exome Aggregation Consortium. The analysis focused on predicted protein-altering alleles that were novel or with an allele frequency less than 0·00005. Variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing using methods previously described.19 We assessed the effect of intronic variants on splicing using Human Splicing Finder.20

For mutagenesis and in-vitro transcription, we used the human SCN4A expression clone, pRc/CMV-hSkM1,21, 22 based on accession M81758.1, which we have previously used for functional expression.14, 23, 24 Site-directed mutagenesis was done with the QuikChange kit (Agilent) and confirmed by sequencing the entire insert.

All identified rare SCN4A mis-sense variants were characterised by patch clamp heterologous expression studies to evaluate the consequence on NaV1.4 channel activity. Functional properties of mutant NaV1.4 channels in expression systems show excellent correlation with predicted changes in excitability of native cells and the clinical phenotype of the patient carrying the variant.7, 12, 13, 14, 25 We assessed expression in HEK293 cells, which do not express endogenous sodium channels.14, 26 The cells were incubated in a 1·9 cm2 well with transfection mixture consisting of 0·5 μg of wild type or mutant human SCN4A plasmid, 50 ng of plasmid coding for copGFP, 1·5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher) in 100 μL of Opti-MEM (ThermoFisher) for 16–24 h. Wild type SCN4A plasmid was included in every set of transfections to control for transfection efficacy. Two independent DNA preparations were used for the Glu1520Lys variant to control for the effect of the quality of the preparation on reduced expression levels.

For whole cell patch clamping, HEK293 cells with green fluorescence were voltage clamped at room temperature 48–72 h after transfection using an Axopatch 200B Amplifier (Axon Instruments), NI-6221 (National Instruments), or Digidata 1440B digitiser and pClamp software (Axon Instruments). Holding voltage was −80 mV. The current–voltage and conductance–voltage relationships were fitted with the Boltzmann equation to estimate the midpoint and the slope factor of the voltage dependence:

where G is electrical conductance, I is current, A is the maximum amplitude, B is the minimum amplitude, V1/2 (voltage of half-maximal activation or inactivation) is the voltage where amplitude is

and Vslope is the slope factor. The time constant of recovery from inactivation (τrecovery) and of onset of fast inactivation (τinactivation) were derived by fitting single or double exponential functions, respectively, to the timecourse data. We analysed only the fast component (routinely >95% of the total amplitude) of the double exponential function. The series resistance error was kept below 5 mV.

We compared the number of ultra-rare and functionally deleterious SCN4A gene variants between cases and controls using a one-tailed Fisher's Exact test. We used Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test with Dunn's pairwise multiple comparisons or a one-way ANOVA with Games-Howell's post-hoc test to compare the mean of each variant against the wild-type mean. We used a Bonferroni correction to correct for multiple comparisons across all parameters.

We analysed the data using pClamp, Microsoft Excel, Origin, Prism, and SPSS 24 software.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

Results

We obtained exome data from 427 SIDS cases (95 from the UK and 332 from the USA) and 729 controls. After sequence alignment, seven cases were excluded from further analysis because less than 75% of the Gencode-defined protein-coding exome was covered by fewer than 20 reads. One further case from a half-sibling pair was excluded from downstream analysis. 141 cases were not white European and were removed from the final analysis. A total of 278 cases (84 from the UK, 194 from the USA) and 729 controls were included in the downstream analysis.

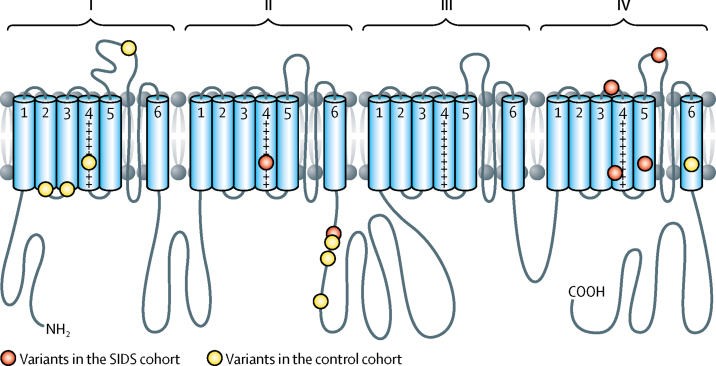

More than 81% of the DNA sequences comprising the protein coding regions and associated splice sites of the SCN4A gene were covered by at least 20 reads in each individual in the study cohort and more than 90% were covered by at least ten reads (appendix p 5). We identified rare alleles in the SCN4A gene in six (2%) of 278 infants of white European descent who died of SIDS and in nine (1%) of 729 ethnically matched controls (p=0·21, one tailed Fisher's Exact test; table 1, figure 1). One of the NaV1.4 variants present in an infant who died from SIDS (Arg1463Ser) was also recorded in the UK national skeletal muscle channelopathy database in an adult patient with myotonia.

Table 1.

Novel and rare SCN4A variants in SIDS cases of European ancestry and ethnically matched controls

| Exome Aggregation Consortium allele frequency | Functional expression results | Position in channel | Age (months) | Sex | Co-sleep? | Evidence of URTI? | Term | Sleep position | Exposed to cigarette smoke? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIDS cases | ||||||||||

| Ser682Trp (2045C→G) | 0·00002626 | Gain of function | DII/S4 | 3 | Male | Yes | No | NA | Prone | Yes |

| Gly859Arg (2575G→A) | 0·00001756 | Wild type like | DII–III cytoplasmic loop | 3 | Female | Yes | No | Full | Prone | NA |

| Val1442Met (4324G→A) | 0·00001025 | Loss of function | DIV/S3-4 extracellular loop | 5 | Male | No | No | Premature | Supine | No |

| Arg1463Ser (4387C→A) | 0·00000832 | Gain of function | DIV/S4 | 3 | Male | Yes | No | Full | Side | Yes |

| Met1493Val (4477A→G) | Novel | Wild type like | DIV/S5 | 3 | Female | No | No | NA | Prone | NA |

| Glu1520Lys (4558G→A) | Novel | Loss of function | DIV/S5–6 pore-forming loop | 2 | Male | NA | Yes | NA | NA | NA |

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Intron change (393-1C→T) | Novel | NA | NA | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Arg179Gln (G536A) | 0·00001862 | Wild type like | DI/S2–3 cytoplasmic loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Arg190Trp (C568T) | Novel | Wild type like | DI/S2–3 cytoplasmic loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Leu227Phe (C679T) | 0·00004441 | Wild type like | DI/S4 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Asp334Asn (G1000A) | 0·00002484 | Wild type like | DI/S5–6 extracellular loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Gly863Arg (G2587A) | 0·00001581 | Wild type like | DII–III cytoplasmic loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Ala870Thr (G2608A) | Novel | Wild type like | DII–III cytoplasmic loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Met897Lys (T2690A) | Novel | Wild type like | DII–III cytoplasmic loop | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Val1590Ile (G4768A) | 0·000008278 | Wild type like | DIV/S6 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

Functional expression results refer to the patch clamp data. NA=not available. URTI=upper respiratory tract infection. D=domain. S=segment.

Figure 1.

The location of mutations in the NaV1.4 channel

The location of mutations in the NaV1.4 channel Transmembrane helices S1–S6 are labelled in domains I–IV. The S4 helices contain positively charged arginine residues (+). The S1–S4 helices form voltage-sensing domains. The S5–S6 helices are pore-forming. The variants in the SIDS cohort (from N-terminus to C-terminus) are: Ser682Trp, Gly859Arg, Val1442Met, Arg1463Ser, Met1493Val, and Glu1520Lys. The variants in the control cohort (from N-terminus to C-terminus) are: Arg179Gln, Arg190Trp, Leu227Phe, Asp334Asn, Gly863Arg, Ala870Thr, Met897Lys, and Val1590Ile. SIDS=sudden infant death syndrome.

Using our whole exome sequencing data, we also determined whether any of the six SIDS cases with a rare SCN4A variant carried a rare variant in any of 90 genes associated with inherited cardiac condition including those associated with SIDS (appendix pp 8–9). Only one such participant did (with variant Ser682Trp in SCN4A). In addition to the SCN4A variant, this individual had variants in SCN5A (Gly333Arg) and in NEXN (Met38Thr).

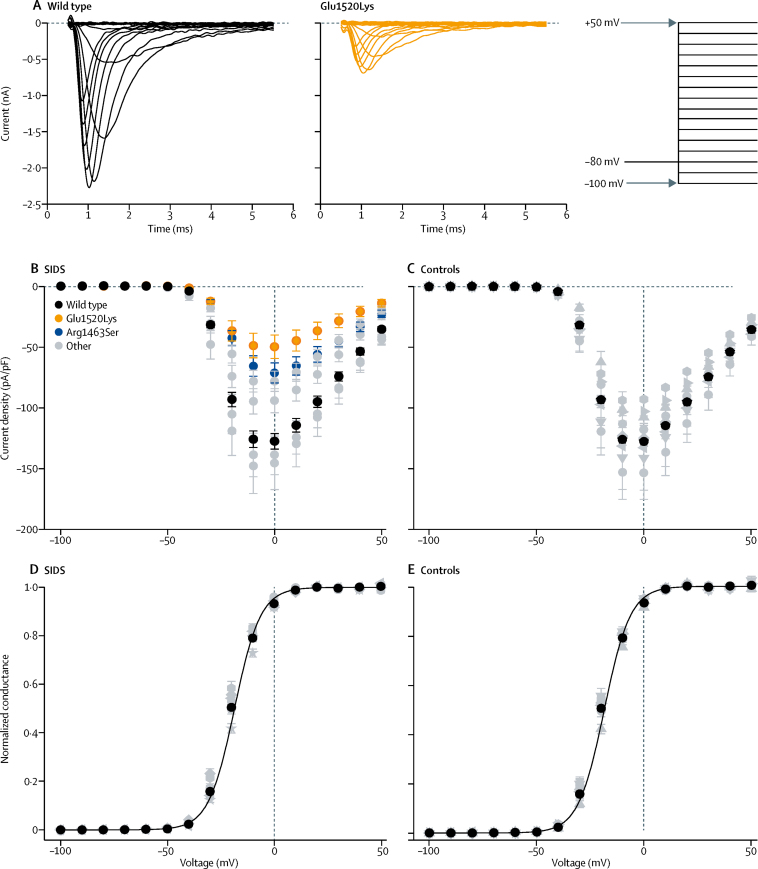

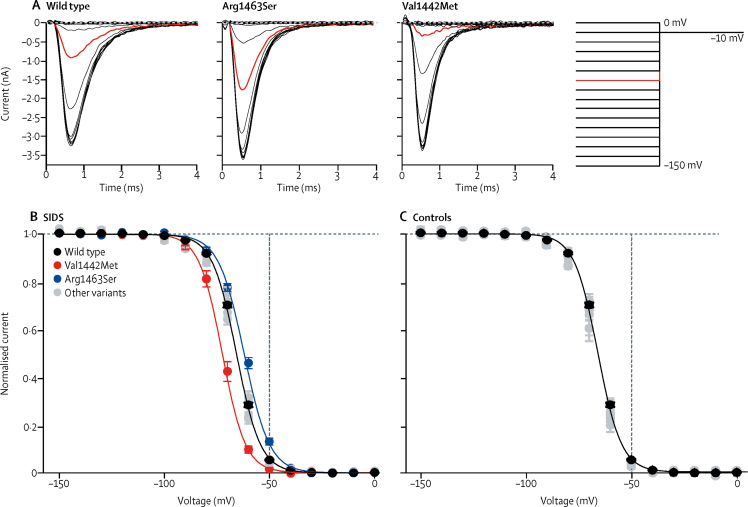

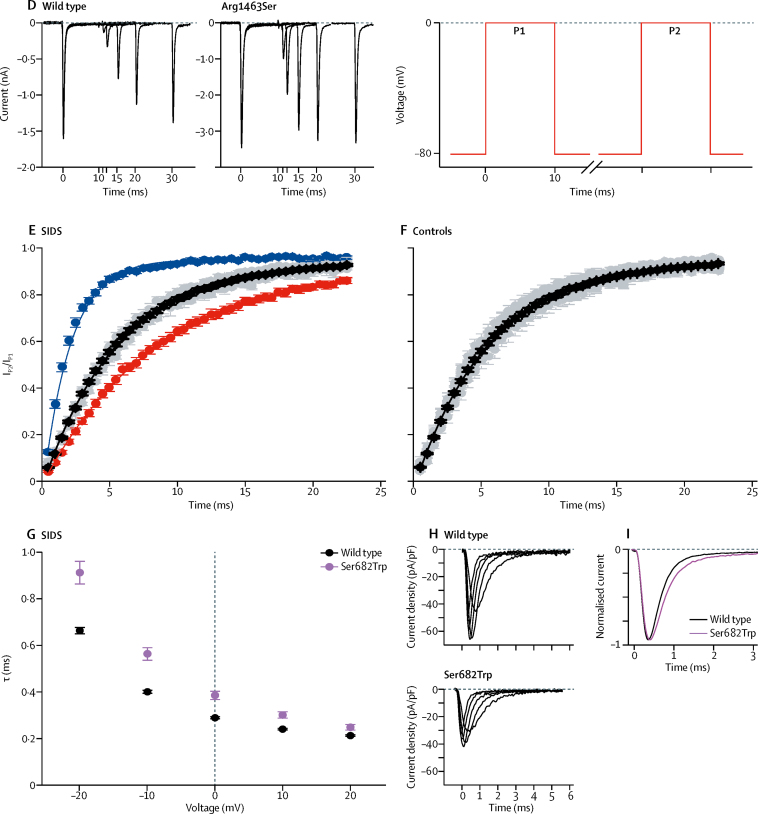

Heterologous expression studies showed that four of the six variants in infants who died of SIDS, but none of the coding variants in controls, disrupted SCN4A function. The voltage dependence of activation for each of the identified alleles was not significantly different from the wild type allele except for a small increase in slope factor (VSlope) for variant Ser682Trp (figure 2D, 2E, table 2). However, the current density in response to a voltage step to 0 mV was significantly reduced for two of the six variants identified in the case cohort (Glu1520Lys, Arg1463Ser; figure 2A, 2B) and none in controls (figure 2C). In addition, the Arg1463Ser variant showed a shift in the voltage of half-maximal fast inactivation to + 3·6 mV (figure 3A, 3B, table 2) and the recovery from inactivation was almost three-times faster than in the wild type channel (figure 3D, 3E, table 2). Furthermore, fast inactivation of Val1442Met was enhanced as the voltage of half-maximal inactivation was 6·6 mV lower in the variant than in wild type and recovery from inactivation was 1·5 times slower (figure 3A, 3B, table 2). The time course of open state inactivation was significantly slower for the Ser682Trp variant at 0 mV (figure 3G–I, table 2). Voltage dependence of inactivation (figure 3C), time constant of recovery from inactivation (figure 3F), and the time constant of inactivation (table 2) of the variants in control cohort did not differ significantly from wild type. The intron variant in the control cohort was predicted to have no effect on splicing (Human Splicing Finder).

Figure 2.

Activation properties of NaV1.4 variants

(A) Representative current traces of wild type, and Glu1520Lys channels in response to test voltages in 10 mV increments from −100 mV to + 50 mV (the voltage protocol is shown on the right). Dashed lines indicate 0 current level. (B,C) Peak current density in response to test voltages ranging from −100 to + 50 mV in 10 mV increments is plotted against the test voltage for variants in the SIDS cohort (B) and in controls (C). Current densities of Glu1520Lys (orange) and Arg1463Ser (blue) were significantly lower than wild type (black; appendix p 6–7). Data for the other variants that did not differ significantly from wild type are shown in grey. (D,E) Voltage dependence of activation. Normalised conductance (peak current/[test voltage – reversal voltage]) is plotted against the test voltage for variants in the SIDS cohort (D) and in controls (E). Individual data were normalised to maximum and minimum amplitude of the Boltzmann fit and averaged. The solid lines represent the fit of Boltzmann equation to mean data. Voltage of half-maximal activation (V1/2) did not differ significantly from wild type (black) for any of the variants (appendix p 6–7) and the data are illustrated with grey symbols. The statistical analysis is shown in the appendix (p 6).

Table 2.

Biophysical parameters of NaV1.4 variants

|

Activation |

Fast inactivation |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | IPeak at 0 mV (pA/pF) | N | V1/2(mV) | Vslope(mV) | V1/2(mV) | Vslope(mV) | τInactivation at 0 mV (ms) | N | TRecovery(ms) | ||

| Wild type | 149 | −127·5 (6·4) | 146 | −19·5 (0·2) | 6·4 (0·1) | −65·3 (0·3) | 5·4 (0·0) | 0·30 (0·00) | 105 | 5·63 (0·14) | |

| SIDS cohort | |||||||||||

| Ser682Trp | 19 | −94·2 (9·9) | 17 | −21·2 (0·7) | 7·2 (0·2)* | −67·0 (0·6) | 5·9 (0·2) | 0·40 (0·02)* | 17 | 6·15 (0·33) | |

| Gly859Arg | 18 | −138·5 (16·4) | 17 | −20·2 (0·8) | 5·7 (0·2) | −64·2 (0·6) | 5·1 (0·1) | 0·31 (0·01) | 17 | 5·20 (0·30) | |

| Val1442Met | 14 | −145·5 (21·7) | 14 | −21·7 (0·8) | 6·3 (0·2) | −71·9 (1·0)* | 5·2 (0·1) | 0·27 (0·01) | 13 | 8·51 (0·46)* | |

| Arg1463Ser | 27 | −71·3 (8·3)* | 25 | −17·4 (0·5) | 6·7 (0·2) | −61·7 (0·6)* | 6·3 (0·1)* | 0·31 (0·01) | 19 | 1·95 (0·09)* | |

| Met1493Val | 17 | −78·2 (8·3) | 17 | −19·2 (0·5) | 6·7 (0·3) | −65·3 (0·8) | 5·5 (0·2) | 0·29 (0·01) | 7 | 5·76 (0·47) | |

| Glu1520Lys | 39 | −49·8 (9·7)* | 28 | −20·3 (0·4) | 6·3 (0·1) | −66·3 (0·5) | 5·4 (0·2) | 0·33 (0·01) | 20 | 5·63 (0·29) | |

| Control cohort | |||||||||||

| Arg179Gln | 11 | −117·6 (11·0) | 11 | −19·3 (0·6) | 6·5 (0·2) | −65·1 (0·7) | 5·1 (0·1) | 0·25 (0·01) | 11 | 4·73 (0·30) | |

| Arg190Trp | 14 | −153·4 (21·8) | 14 | −20·7 (0·5) | 6·4 (0·2) | −64·9 (0·5) | 5·3 (0·1) | 0·29 (0·01) | 13 | 5·09 (0·20) | |

| Leu227Phe | 12 | −107·7 (16·1) | 12 | −17·6 (0·4) | 6·5 (0·2) | −67·8 (0·8) | 5·6 (0·1) | 0·33 (0·02) | 10 | 5·33 (0·30) | |

| Asp334Asn | 10 | −141·0 (26·6) | 10 | −21·0 (0·9) | 6·4 (0·2) | −66·4 (0·8) | 5·3 (0·1) | 0·27 (0·01) | 9 | 5·07 (0·30) | |

| Gly863Arg | 12 | −124·6 (15·8) | 12 | −20·3 (0·8) | 6·3 (0·1) | −66·1 (0·7) | 5·2 (0·2) | 0·29 (0·01) | 10 | 5·71 (0·21) | |

| Ala870Thr | 16 | −132·6 (20·0) | 15 | −20·0 (0·6) | 6·4 (0·1) | −65·7 (0·6) | 5·0 (0·1) | 0·29 (0·01) | 14 | 6·29 (0·55) | |

| Met897Lys | 10 | −102·8 (23·3) | 9 | −20·4 (0·7) | 6·8 (0·3) | −67·7 (1·3) | 5·5 (0·2) | 0·31 (0·02) | 7 | 6·21 (0·54) | |

| Val1590Ile | 8 | −92·8 (13·2) | 8 | −20·7 (0·6) | 6·8 (0·2) | −65·8 (0·9) | 5·4 (0·2) | 0·30 (0·02) | 7 | 5·73 (0·61) | |

Data are mean (SE). N indicates the number of cells recorded from. IPeak includes all cells with current amplitude larger than 0·1 nA. Only cells with IPeaklarger than 0·5 nA were included in the analysis of the other biophysical properties. Voltage dependence of activation and fast inactivation, and time constant of open state fast inactivation were all analysed in the same recording for each cell.

p value compared with wild type is less than the Bonferroni threshold (p=0·00051; 98 tests from 14 variants and seven parameters). The appendix shows uncorrected p values (p 6–7). Ipeak=peak current density. V1/2=the voltage of half-maximal activation or inactivation. Vslope=slope factor. τInactivation=time constant of open state fast inactivation. TRecovery=time constant of recovery from inactivation.

Figure 3.

Fast inactivation properties of NaV1.4 variants

(A–C) Voltage dependence of fast inactivation. (A) Representative current traces in response to tail voltage step to −10 mV following 150 ms pre-pulse voltage steps ranging from −150 mV to 0 mV in 10 mV increments for wild type, Arg1463Ser, and Val1442Met variants. First 5 ms of the voltage step to −10 mV are shown. Current response following pre-pulse step to −60 mV is highlighted in red. The voltage protocol is shown to the right. Dashed lines indicate 0 current level. (B,C) The peak tail current amplitude at −10 mV is plotted against the pre-pulse voltage for variants in the SIDS cohort (B) and in controls (C). Individual data were normalised to maximum and minimum values of the Boltzmann equation and averaged. Voltage of half-maximal inactivation was shifted significantly to more hyperpolarised voltages for Val1442Met channels (red) and to more depolarised voltages for Arg1463Ser channels (blue). The solid lines represent the fit of Boltzmann equation to mean data for wild type, Val1442Met and Arg1463Ser channels. The data for the variants that did not differ from wild type channels are shown in grey. (D–F) Recovery rate from fast inactivation. (D) Representative current traces for wild type and Arg1463Ser channels illustrating the recovery from inactivation. Channels were inactivated by a 10 ms voltage step to 0 mV and then stepped to recovery voltage of −80 mV for an increasing duration of time. A second voltage step to 0 mV was then applied to see how much the channels had recovered from fast inactivation. Only traces with 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 ms duration at recovery voltage of −80 mV are shown. The voltage protocol is shown to the right. (E,F) The peak current amplitude during the second step (P2) is divided by the peak current amplitude during the first voltage step (P1) and plotted against the duration of the recovery period at −80 mV. Data for variants in the SIDS cohort (E) and in controls (F) is colour coded as in (B) and (C). The solid lines represent fit of exponential function to the mean data. (G–I) Rate of fast inactivation. (G) Time constant (τ) of inactivation at voltages ranging from −20 mV to +20 mV for wild type (black) and Ser682Trp (magenta) channels. The voltage protocol was as in figure 2A. Only the time constant of the fast component that carries roughly 95% of the amplitude of the inactivating current is analysed. (H) Representative current traces at −20 mV to +20 mV for wild type (top) and Ser682Trp (bottom) channels, showing the slower inactivation of the Ser682Trp variant. (I) Overlay of mean normalised current traces for wild type (black) and Ser682Trp (magenta) channels in response to voltage step to 0 mV.

We initially tested our hypothesis in a UK cohort. Genetic data were available from 84 white Europeans. Of these UK cases, one carried a functional SCN4A variant, Arg1463Ser. This was an underpowered cohort but this positive finding warranted testing our hypothesis in a larger cohort. We then analysed genetic data in a second cohort that included 194 DNA samples from cases of white European descent from the USA to assess whether our finding could be replicated. Three (1·5%) of 194 infants in this second cohort carried functional SCN4A variants, compared with none of 729 ethnically matched controls (p=0·009 Fisher's exact test).

Taking the UK and US cohorts of 278 cases together, four of the six rare variants in the SIDS cohort had significant differences in channel gating compared with wild type SCN4A (Figure 2, Figure 3, and table 2); by contrast, none of the variants in controls had any differences from wild type SCN4A (p= 0·011, Fisher's exact test). Therefore, four of 278 SIDS cases had a functionally disruptive SCN4A missense variant (1·4%) compared with none of the 729 ethnically matched controls (p=0·0057, Fisher's exact test). Even if the intron variant in the control cohort is assumed to be deleterious, functional variants remain over-represented in the SIDS group (p=0·02).

Discussion

We identified rare SCN4A variants in both Caucasian European infants who died of SIDS and in living adult controls. We showed that rare variants that alter NaV1.4 channel function in a similar fashion to known pathogenic SCN4A variants were over-represented in infants who had died of SIDS compared with ethnically matched controls.

Alterations in sodium channel function in SIDS are qualitatively similar to those reported in infants with life-threatening respiratory events.9, 12, 14 Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function SCN4A variants can cause severe respiratory presentations in infancy and some of these cases have had a fatal outcome.8, 9, 14 In our study, only the SCN4A variants present in white SIDS cases caused significant alterations in channel function compared with wild type. By contrast, the variants we discovered in control adults did not alter channel function. The Arg1463Ser and Ser682Trp variants caused impaired fast inactivation that resulted in a predominantly gain-of-function effect in the NaV1.4 sodium channel. Similar gain-of-function alterations in channel function are the hallmark of SCN4A variants in patients with myotonia, including in infants with severe respiratory complications.25 The pathogenic role of Arg1463Ser is also supported by its presence in a patient under our care (EM, MGH) with generalised myotonia. The heterozygous loss-of-function variants we discovered in the SIDS cohort caused either substantial enhancement of fast inactivation (Val1442Met) or reduced current density (Glu1520Lys). Compound heterozygous or homozygous loss-of-function NaV1.4 variants (including the previously reported Val1442Met variant) cause myasthenic syndrome and congenital myopathy.12, 14 Some of these patients need respiratory support.12, 14 These observations support the notion that disrupted sodium channel function in the respiratory muscles can contribute to life-threatening events.

Developmental regulation of SCN4A expression and muscle fibre typing might define a period of SIDS vulnerability. The SIDS infants in our cohort would have appeared healthy and asymptomatic before death. We propose that the functionally deleterious variants we have identified can explain this apparent healthiness of infants and also represent a major risk factor for SIDS. The gain-of-function change we observed in the infant with Arg1463Ser is consistent with previously reported SCN4A variants (appendix pp 1–4) that, after a period of apparent clinical normality, cause myotonia of the laryngeal and respiratory muscles precipitating an abrupt onset apnoeic crisis. For those with heterozygous loss-of-function variants (Val1442Met and Glu1520Lys) and the milder gain-of-function variant (Ser682Trp), the level of channel perturbation shown in our study might not be sufficient to cause respiratory failure but it could be a significant contributing factor. Baseline respiratory function could be normal but the presence of these variants might impair the ability of respiratory muscles to mount and maintain rapid and forceful contraction in response to hypoxia.4

Two developmental factors might combine with the functional effects of the SCN4A variants we identified to render respiratory muscles more susceptible to contractile failure—eg, in response to hypoxia. First, developmental alterations in skeletal muscle sodium channel expression: during embryogenesis two different sodium channel isoforms, the cardiac isoform NaV1.5 (encoded by SCN5A) and the skeletal muscle isoform NaV1.4 are expressed in skeletal muscle although NaV1.4 predominates. The expression of NaV1.5 progressively decreases over the first 2 years after birth. The expression of NaV1.4 progressively increases after birth but the level before the age of 5 years is 25–40% of that seen in adulthood.27 The presence of NaV1.5 expression could compensate to some degree for variant-induced NaV1.4 dysfunction and to the delay in onset of symptoms reported in patients with myotonia who have NaV1.4 dysfunction.27

Low expression of NaV1.4 in infantile muscle is likely to be particularly crucial in fast twitch respiratory muscles28, 29, 30 because their ability to maintain the amplitude of successive action potentials when under increased demand—eg, in the presence of hypoxia—is dependent on the density of sodium channels.31, 32 This suggestion is supported by the observation that the capacity of muscle fibres from NaV1.4 heterozygous null mice to generate sustained action potentials diminishes with repeated stimulation.33 The enhanced sodium channel inactivation we observed with the Val1442Met variant will reduce channel availability, which could be particularly detrimental during such high frequency stimulation.13

Second, developmental alterations in respiratory muscle fibre typing: the proportion of fast and slow twitch fibres in respiratory muscles is regulated developmentally. Fast twitch fibres that rely more heavily on the density of sodium channels predominate in these muscles in infants, compared with those older than 2 years of age.34

These developmental changes in sodium channel expression patterns and in muscle fibre type composition could define a period of vulnerability in early life when the respiratory and laryngeal muscles are particularly dependent on NaV1.4 channel function. Our data support the notion that the NaV1.4 dysfunction caused by the SCN4A variants will exacerbate this vulnerability.

Several related concurrent events are thought necessary for sudden infant death.35 A triple risk hypothesis36, 37 states that for death to occur there must be a convergence of factors: a vulnerable infant, a critical period of development, and an external stressor. Our data suggest that the presence of an SCN4A gene variant that impairs sodium channel function exacerbates an infant's vulnerability. In addition, the notion of developmental regulation of respiratory muscle fibre types and muscle sodium channel expression may define a critical period of development when they are particularly vulnerable to respiratory stressors. Fasting-induced alterations in extracellular potassium that might occur during sleep could further exacerbate the deleterious gain-of-channel function effects. Our data are consistent with the notion that risk factors combine to increase the probability of SIDS occurring, but may not be the sole cause of death. This hypothesis concurs with the presence of some very rare variants with effects on NaV1.4 function in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database. If the SCN4A gene changes with an effect on channel function were individually or universally fatal, they would be unlikely to be present in living controls. Parallels can be made with studies of variants in SCN5A cardiac sodium channel and the β subunits of Nav1.5 in infants who die from SIDS.38, 39 Functional variants in these genes can predispose patients to cardiac arrhythmia but they are also rarely found in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database, indicating that they contribute to the probability of death occurring but might not define it.40 One of our SIDS cases (Ser682Trp) did also carry ultra rare variants in the SCN5A (Gly333Arg) and NEXN (Met38Thr) cardiac genes. Although other variants in SCN5A have been linked to arrhythmia syndromes and SIDS, this specific variant has not been reported in either of these presentations and has not been functionally characterised. It occurs in an extracellular loop of the protein that is not a critical domain for protein function but the aminoacid is conserved across species.41 Variants in NEXN have been associated with inherited cardiomyopathy42 but no link with the risk of SIDS has been established. The significance of these variants is therefore unknown. Our findings are the first direct evidence that a primary defect in skeletal muscle excitability might be a risk factor for SIDS.

Our study had several limitations. It was restricted to the examination of SCN4A variants in European white individuals. SIDS occurs in all ethnicities at varying rates and our study should be replicated in other ethnic groups. Because of the anonymity of our samples, little clinical data were available and other family members could not be tested. Our functional analyses were also restricted to effects on sodium channel gating properties in vitro.

Our data show that functionally disruptive SCN4A variants are over-represented in SIDS. We propose that such variants impair the ability of respiratory muscles to respond to hypoxia. The developmental regulation of sodium channel expression and skeletal muscle fibre type composition may be factors in the period of susceptibility. Although we have studied two cohorts, which together form one of the largest SIDS cohorts reported,43 replication in other cohorts is needed to evaluate the potential role of SCN4A variants as a risk factor in SIDS. In addition, prospective studies with direct family involvement will help to define the clinical correlation of in-vitro muscle sodium channel dysfunction with SIDS.

Sodium channel blockers can reduce the frequency and severity of myotonia in patients with gain-of-function NaV1.4 variants,44 including those with severe infantile myotonia who have life-threatening respiratory compromise (appendix pp 1–4).8, 9 Furthermore, acetazolamide, which may be effective in loss-of-function SCN4A channelopathies,12, 45 has been reported to abolish attacks of respiratory and bulbar weakness in a patient with myasthenic syndrome associated with the Val1442Glu loss-of-function variant.12 These data suggest that drug treatment could reduce the risk of SCN4A variants in siblings of an index case, but this requires further detailed evaluation. In conclusion, our data suggest that SCN4A variants are a genetically and mechanistically plausible risk factor for SIDS.

For the Exome Aggregation Consortium see http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

For the Human Splicing Finder see http://www.umd.be/HSF3/HSF.shtml

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases is supported by a Medical Research Council grant (MR/K000608/1). RM is supported by the Medical Research Council (grant MR/M006948/1). LW was supported by a British Heart Foundation fellowship (FS/13/78/30520) and additional funds from Biotronik and Cardiac Risk in the Young. MGT was funded by a Medical Research Council PhD studentship. MGH is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University College London, and receives research funding from the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign. EM is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, University College London, and the Wellcome Trust. Part of this work was undertaken at University College London Hospitals and University College London, which receives funding from the Department of Health's National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. ERB is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England and The Robert Lancaster Memorial Fund sponsored by McColl's Retail Group. SMS received funding from Dravet Syndrome UK, the Epilepsy Society, and the Wellcome Trust. We also acknowledge support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, in partnership with the King's College London. DJT and MJA are supported by the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program. DJT and MJA received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (award number R01HD042569). DMK is supported by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Ankur Chakravarthy (Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada) for help with statistics and Stephanie Schorge (University College London, London, UK) for detailed characteristics of the HEK cell line used in this work. pRc/CMV-hSkM1 was a gift from S C Cannon (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, USA).

Contributors

RM, MGH, ERB, and EM designed the study and wrote the report. RM, LW, MGT, DJT, and EM designed the figures and tables. RM, LW, DJT, MGT, DRF, MJE, IJMJ, JT-H, MCC, PJF, AJ, MAS, MJA, and ERB collected data. RM, LW, DJT, MGT, RS, DMK, MGS, CL, SMS, AJ, MAS, MJA, MGH, ERB, and EM analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data and provided feedback on the report.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR. Sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370:1578–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakeem GF, Oddy L, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Incidence and determinants of sudden infant death syndrome: a population-based study on 37 million births. World J Pediatr. 2015;11:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s12519-014-0530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiter JC, Bohm I. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in the sudden infant death syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinney HC, Thach BT. The sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:795–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0803836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel AL, Harris K, Thach BT. Inspired CO(2) and O(2) in sleeping infants rebreathing from bedding: relevance for sudden infant death syndrome. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;91:2537–2545. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horga A, Raja Rayan DL, Matthews E. Prevalence study of genetically defined skeletal muscle channelopathies in England. Neurology. 2013;80:1472–1475. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828cf8d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon SC. Channelopathies of skeletal muscle excitability. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:761–790. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gay S, Dupuis D, Faivre L. Severe neonatal non-dystrophic myotonia secondary to a novel mutation of the voltage-gated sodium channel (SCN4A) gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:380–383. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lion-Francois L, Mignot C, Vicart S. Severe neonatal episodic laryngospasm due to de novo SCN4A mutations: a new treatable disorder. Neurology. 2010;75:641–645. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ed9e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews E, Manzur AY, Sud R, Muntoni F, Hanna MG. Stridor as a neonatal presentation of skeletal muscle sodium channelopathy. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:127–129. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshinaga H, Sakoda S, Good JM. A novel mutation in SCN4A causes severe myotonia and school-age-onset paralytic episodes. J Neurol Sci. 2012;315:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsujino A, Maertens C, Ohno K. Myasthenic syndrome caused by mutation of the SCN4A sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7377–7382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230273100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold WD, Feldman DH, Ramirez S. Defective fast inactivation recovery of Nav 1.4 in congenital myasthenic syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:840–850. doi: 10.1002/ana.24389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaharieva IT, Thor MG, Oates EC. Loss-of-function mutations in SCN4A cause severe foetal hypokinesia or ‘classical’ congenital myopathy. Brain. 2016;139:674–691. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Sidebotham PD, Hayler T. Investigating sudden unexpected deaths in infancy and childhood and caring for bereaved families: an integrated multiagency approach. BMJ. 2004;328:331–334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willinger M, James LS, Catz C. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): deliberations of an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatr Pathol. 1991;11:677–684. doi: 10.3109/15513819109065465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price AL, Weale ME, Patterson N. Long-range LD can confound genome scans in admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manichaikul A, Mychaleckyj JC, Rich SS, Daly K, Sale M, Chen WM. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews E, Labrum R, Sweeney MG. Voltage sensor charge loss accounts for most cases of hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Neurology. 2009;72:1544–1547. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342387.65477.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chahine M, Bennett PB, George AL, Jr, Horn R. Functional expression and properties of the human skeletal muscle sodium channel. Pflugers Arch. 1994;427:136–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00585952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu FF, Gordon E, Hoffman EP, Cannon SC. A C-terminal skeletal muscle sodium channel mutation associated with myotonia disrupts fast inactivation. J Physiol. 2005;565:371–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonorazky HD, Marshall CR, Al-Murshed M. Congenital myopathy with “corona” fibres, selective muscle atrophy, and craniosynostosis associated with novel recessive mutations in SCN4A. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27:574–580. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrochano S, Mannikko R, Joyce PI. Novel mutations in human and mouse SCN4A implicate AMPK in myotonia and periodic paralysis. Brain. 2014;137:3171–3185. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Jr, Cannon SC. Inactivation defects caused by myotonia-associated mutations in the sodium channel III-IV linker. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:559–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fletcher EV, Kullmann DM, Schorge S. Alternative splicing modulates inactivation of type 1 voltage-gated sodium channels by toggling an amino acid in the first S3-S4 linker. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36700–36708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.250225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Hoffman EP. Pathophysiology of sodium channelopathies. Studies of sodium channel expression by quantitative multiplex fluorescence polymerase chain reaction. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18563–18571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polla B, D'Antona G, Bottinelli R, Reggiani C. Respiratory muscle fibres: specialisation and plasticity. Thorax. 2004;59:808–817. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.009894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoh JF. Laryngeal muscle fibre types. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183:133–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas CA, Rughani A, Hoh JF. Expression of extraocular myosin heavy chain in rabbit laryngeal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1995;16:368–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00114502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruff RL, Whittlesey D. Na+ currents near and away from endplates on human fast and slow twitch muscle fibers. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:922–929. doi: 10.1002/mus.880160906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milton RL, Behforouz MA. Na channel density in extrajunctional sarcolemma of fast and slow twitch mouse skeletal muscle fibres: functional implications and plasticity after fast motoneuron transplantation on to a slow muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1995;16:430–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00114508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu F, Mi W, Fu Y, Struyk A, Cannon SC. Mice with an NaV1.4 sodium channel null allele have latent myasthenia, without susceptibility to periodic paralysis. Brain. 2016;139:1688–1699. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keens TG, Bryan AC, Levison H, Ianuzzo CD. Developmental pattern of muscle fiber types in human ventilatory muscles. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1978;44:909–913. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergman AB, Ray CG, Pomeroy MA, Wahl PW, Beckwith JB. Studies of the sudden infant death syndrome in King County, Washington. 3. Epidemiology. Pediatrics. 1972;49:860–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spinelli J, Collins-Praino L, Van Den Heuvel C, Byard RW. Evolution and significance of the triple risk model in sudden infant death syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53:112–115. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filiano JJ, Kinney HC. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model. Biol Neonate. 1994;65:194–197. doi: 10.1159/000244052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang DW, Desai RR, Crotti L. Cardiac sodium channel dysfunction in sudden infant death syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:368–376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan BH, Pundi KN, Van Norstrand DW. Sudden infant death syndrome-associated mutations in the sodium channel beta subunits. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ackerman MJ, Siu BL, Sturner WQ. Postmortem molecular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2001;286:2264–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ensembl Genome Browser https://www.ensembl.org/index.html (accessed March 19, 2018).).

- 42.Hassel D, Dahme T, Erdmann J. Nexilin mutations destabilize cardiac Z-disks and lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/nm.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fard D, Laer K, Rothamel T. Candidate gene variants of the immune system and sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s00414-016-1347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Statland JM, Bundy BN, Wang Y. Mexiletine for symptoms and signs of myotonia in nondystrophic myotonia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308:1357–1365. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens JAE, Matthews E, Hanna M, Muntoni F, Sud R, Hartley L. Acetazolamide to treat congenital myopathy caused by SCN4A mutation. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21:e224–e225. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.