Abstract

Hypoxia represents a major physiological challenge for prawns and is a problem in aquaculture. Therefore, an understanding of the metabolic response mechanism of economically important prawn species to hypoxia and re-oxygenation is essential. However, little is known about the intrinsic mechanisms by which the oriental river prawn Macrobrachium nipponense copes with hypoxia at the metabolic level. In this study, we conducted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics studies and assays of energy metabolism-related parameters to investigate the metabolic mechanisms in the hepatopancreas of M. nipponense in response to 2.0 O2/L hypoxia for 6 and 24 h, and reoxygenation for 6 h following hypoxia for 24 h. Prawns under hypoxic stress displayed higher glycolysis-related enzyme activities and lower mRNA expression levels of aerobic respiratory enzymes than those in the normoxic control group, and those parameters returned to control levels in the reoxygenated group. Our results showed that hypoxia induced significant metabolomic alterations in the prawn hepatopancreas within 24 h. The main metabolic alterations were depletion of amino acids and 2-hydroxybutanoic acid and accumulation of lactate. Further, the findings indicated that hypoxia disturbed energy metabolism and induced antioxidant defense regulation in prawns. Surprisingly, recovery from hypoxia (i.e., reoxygenation) significantly affected 25 metabolites. Some amino acids (valine, leucine, isoleucine, lysine, glutamate, and methionine) were markedly decreased compared to the control group, suggesting that increased degradation of amino acids occurred to provide energy in prawns at reoxygenation conditions. This study describes the acute metabolomic alterations that occur in prawns in response to hypoxia and demonstrates the potential of the altered metabolites as biomarkers of hypoxia.

Keywords: Macrobrachium nipponense, metabolomics, hypoxia, hepatopancreas, oxidative stress

Introduction

The level of dissolved oxygen is a key indicator of water quality, and partially determines the intensity of crustacean aquaculture. Much research has focused on the negative effects of hypoxia on crustaceans. At hypoxic conditions, tissues must increase anaerobic energy production, improve energy use, or lower energy consumption. The responses of crustaceans to hypoxia may result in physiological, cellular, molecular and behavioral changes that depend on the duration and level of the hypoxic stress: these changes can be seen in the behavioral responses of some species (Wu, 2002; Bell and Eggleston, 2005; Craig et al., 2005), oxygen transport (Mangum and Rainer, 1988; Mangum, 1997), growth and reproduction (Ocampo et al., 2000; Brown-Peterson et al., 2008, 2011), immune response (Qiu et al., 2011; Kniffin et al., 2014), transcriptomic responses (Li and Brouwer, 2009, 2013; Sun et al., 2015), and proteomic responses (Jiang et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2016b). However, in physiology research on aquatic invertebrates, no study to date has reported a comparative analysis of the metabolome profiles in crustaceans under hypoxic conditions.

Recently, metabolomics studies have been widely applied in aquatic animals to elucidate the biological effects of hypoxic stressors on organisms (Hines et al., 2007; Hallman et al., 2008; Tuffnail et al., 2009; Lardon et al., 2013a,b). Several analytical techniques have been well established and are frequently applied in metabolomics studies (Luo et al., 2007; Nudi et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017), such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Among these analytical techniques, GC-MS is frequently used in metabolomics studies and is highly sensitive and reproducible (Ruan et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2015). Importantly, GC-MS-based metabolomics analysis has been used to investigate the biological effects of sulfide pollution in shrimp (Li et al., 2017). Their work confirmed the applicability of GC-MS-based metabolomics analysis to characterize the biological effects of environmental stressors in crustaceans.

Macrobrachium nipponense (Crustacea; Decapoda; Palaemonidae), also called the oriental river prawn, is an important aquaculture species that is distributed widely in freshwater and low-salinity estuarine regions in Asia (Ma et al., 2011). Prawns are relatively susceptible to hypoxia compared with most crustaceans (Sun et al., 2015). Thus, in prawn production, hypoxia may cause large economic losses because of increased mortality and decreased growth rate. In crustaceans, the functions of the hepatopancreas include carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, energy storage and breakdown (Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, we hypothesized that the M. nipponense hepatopancreas undergoes marked metabolomic changes in response to hypoxia (Liu et al., 2014; Song Q. et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the specific mechanisms by hepatopancreas of prawns respond to hypoxia stress are largely unknown and hypoxia-related metabolomics information remains limited. Thus, the effects of hypoxia and subsequent recovery on M. nipponense hepatopancreas were investigated using a GC-MS-based metabolomics approach. We also compared the activities of metabolic enzymes and electron transport chain-related gene expression level changes induced by hypoxia between M. nipponense and other species. This study provides insight into the metabolic pathways of M. nipponense that are affected by acute hypoxia and reoxygenation.

Materials and methods

Experimental prawn

All experimental procedures involving prawn were approved by the institution animal care and use committee of the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences. Healthy M. nipponense (wet weight 2.12–3.86 g) were obtained from Dapu experimental base near by Tai Lake, the Freshwater Fisheries Research Center of the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Wuxi, China). The prawns were acclimated in 12,300-L aerated freshwater tanks for 1 week and fed commercial flake food twice per day. The culture conditions were: 23.5 ± 0.5°C, pH 8.3 ± 0.09, 6.8 ± 0.2 mg/L dissolved oxygen, and < 0.1 mg/L total ammonia-nitrogen. The prawn were raised under the natural photoperiod.

Hypoxia and recovery stress

The control group was maintained in normoxic conditions (6.5 ± 0.2 mg O2/L). In the hypoxia groups, severe hypoxic conditions (2.0 ± 0.1 mg O2/L) for 24 h within the treatment tanks were maintained by adding N2 gas until the desired O2 concentrations were reached (Sun et al., 2014); oxygen levels were maintained by adding N2 gas when needed. The hypoxic DO value was chosen based on previous observations of juvenile oriental river prawn. DO and temperature were measured using a water-quality instrument (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Six hundred prawns were randomly allocated to 12 tanks (four treatments were conducted in triplicate): hypoxia for 0 h (control), severe hypoxia for 6 h, severe hypoxia for 24 h, or severe hypoxia for 24 h followed by recovery in normoxic conditions for 6 h. The mortality rate was 10% during experiment period. The hepatopancreas samples in each group (in triplicate) were also collected for the biochemical and gene expression assays (n = 9), and the other hepatopancreas samples in each group (in triplicate) were also stored at −80°C until the metabolomics assays were conducted (n = 8). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Experimental Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Chen et al., 2017). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences.

Hepatopancreas metabolomics analysis

Samples (0.05 g, n = 8) in each group were extracted with 0.4 mL methanol-chloroform (v:v, 4:1). l-2-chlorophenylalanine (20 μL) was added as an internal standard and then centrifuged (11,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C). The supernatant was then transferred to a 2-ml GC/MS glass vial, and 15 μL from each sample were analyzed for quality control purposes. The hepatopancreas extracts were processed using a method described in a recent study (Li et al., 2017).

GC-time-of-flight (TOF)-MS analysis was conducted using an Agilent 7890 GC system coupled with a Pegasus HT TOF-MS, as previously described (Li et al., 2017). Each sample in the present study was analyzed eight times. Chroma TOF4.3X software (LECO Corporation, USA) and the LECO-Fiehn Rtx5 database were used for raw peak extraction, data baseline filtering and calibration, peak alignment, deconvolution analysis, peak identification, and integration of peak areas (Kind et al., 2009). Metabolomics data have been deposited to the EMBL-EBI MetaboLights database (Haug et al., 2013) with the identifier MTBLS481. The complete dataset can be accessed https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS584.

Analysis of differential metabolites

Three-dimensional data including the peak number, sample name, and normalized peak area were processed using the SIMCA14 software package (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden) for principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projections to latent structures-discriminate analysis (OPLS-DA). PCA showed the distribution of the original data. OPLS-DA showed a higher level of group separation and thus resulted in a better understanding of the variables responsible for classification (i.e., the differences between groups). We refined this analysis by obtaining the first principal component of variable importance projection values, with values >1.0 selected as changed metabolites. In step 2, the remaining variables were then assessed using Student's t-test (P < 0.05) (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003; Ren et al., 2015; Song T. et al., 2017). Metabolites and their biological roles and pathways were identified using databases including Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chebi/init.do), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (http://www.nist.gov/index.html). KEGG pathway analysis of different metabolites was performed using Metabo Analyst 3.0 software (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/MetaboAnalyst/).

RNA extraction and quantitation of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from hepatopancreas (~100 mg) using 1 mL of Trizol reagent following the manufacturer's protocol (TaKaRa, Japan). cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg total DNA-free RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative real time-PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ5 Real-Time PCR system, and β-actin was used as a reference gene (Sun et al., 2016a). Table 1 shows the primers used. The reaction was amplified with 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, which were followed by 10 min of incubation at 72°C as a final extension step (Qiao et al., 2015). Dissociation curve analysis of the amplification products was performed at the end of each PCR reaction. mRNA expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Table 1.

Primers used for qPCR.

| Target mRNA | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I-F | TATTAGGAGCGCCAGACATAGC |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I-R | GGGGTAGACAGTTCATCCTGTG |

| ATPase subunit α-F | AGGTATCCTTGGCCGTGTTG |

| ATPase subunit α-R | TTGCCAGTCTGACGATCACC |

| ATPase subunit β-F | TGAGGTCAACTTTCCCCGAC |

| ATPase subunit β-R | CCTGGGCCAAACTTCTTGAC |

| β-actin-F | AATGTGTGACGACGAAGTAG |

| β-actin-R | GCCTCATCACCGACATAA |

Analysis of enzyme activity

Hepatopancreas samples were homogenized (w:v, 1:10) in ice-chilled 0.86% saline buffer at 60 Hz for 30 s, and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected for further analysis. The succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), hexokinase (HK), pyruvate kinase (PK), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities of each sample were determined using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), including succinate dehydrogenase assay kit (A022, colorimetric method, 50 tubes), hexokinase assay kit (A077-1, ultraviolet colorimetric method, 30 tubes), pyruvate kinase assay kit (A076-1, ultraviolet colorimetric method, 50 tubes), and lactate dehydrogenase assay kit (A020-2, microplate method, 96 tubes).Protein concentration in the samples was determined according to the Bradford method 1976, with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SE values (n = 9). Data were transformed if necessary after evaluating assumptions of normality, equality of variances and outliers, and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the software SPSS 19.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows, with post-hoc comparison of means using the Turkey-Kramer HSD test.

Results

Hepatopancreas metabolomic profile of M. nipponense in response to hypoxia and reoxygenation

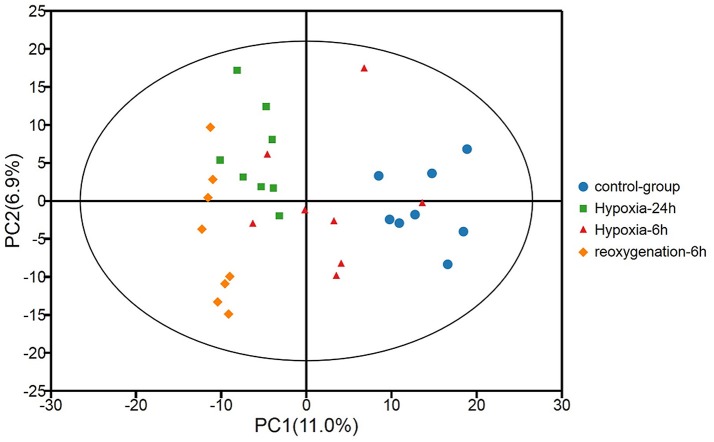

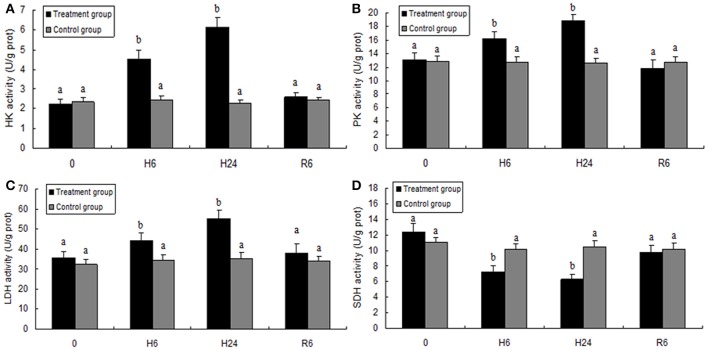

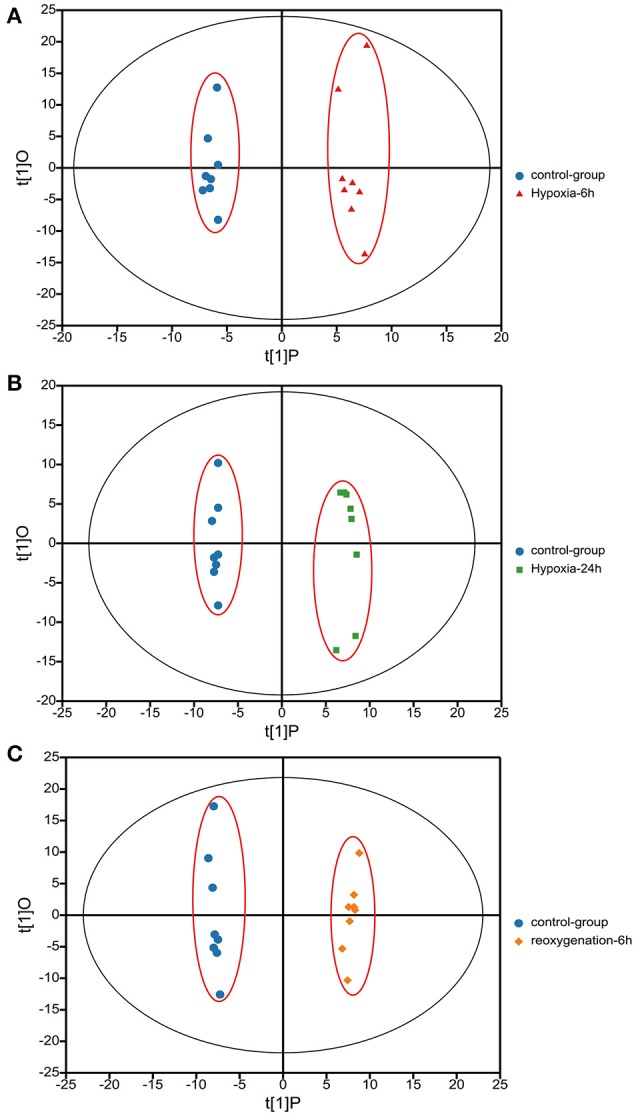

Metabolic profiles of prawn hepatopancreas acquired in present study were shown in Figure S1. PCA analysis of GC-TOF/MS metabolic profiles of hepatopancreas showed in Figure 1, a certain trend in metabolite shift was observed among different groups in PC1. Due to the relatively short period of hypoxia stress compared to the lifespan of a river prawn, the major metabolite pathways might remain generally stable. As a result, we believe that the metabolic shift only covered a small portion of the total metabolome data in this experiment. OPLS-DA was also applied to each sample (hypoxia or reoxygenation), and data were compared with the control group (Figure 2). The classification parameters for the software were as follows: R2Y = 0.988 and Q2Y = 0.502, R2Y = 0.994 and Q2Y = 0.698, and R2Y = 0.996 and Q2Y = 0.777 for 6-h hypoxia, 24-h hypoxia and 6-h reoxygenation, respectively. Seven-fold cross-validation was used to estimate the robustness and predictive ability of our model, and permutation tests were used to further validate the model. The R2 and Q2 intercept values were 0.97, 0.95, 0.94, and −0.34, −0.55, −061, respectively, after 200 permutations for different treatments. The low Q2 intercept values indicate the robustness of the models, the low risk of overfitting and the reliability of the method. The OPLS-DA score plots of the first and second principal components (t [1] P and t [1] O) showed that the prawns under hypoxia for 6 h, hypoxia for 24 h, and hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h were clearly separated from those in control conditions in the direction of t [1] P. Thus, the spectral characteristics of the three experimental groups were markedly different from those of the control group.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolic profiles of the hepatopancreas of oriental river prawns in the control group, in response to hypoxia for 6 and 24 h, and in response to hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h (eight biological replicates). R2X [1] = 0.111, R2X [2] = 0.179, Ellipse: Hotelling's T2 (95%).

Figure 2.

Orthogonal projections to latent structures-discriminate analysis (OPLS-DA) score plots based on the GC-MS spectra of hepatopancreas samples from M. nipponense in response to hypoxia for 6 h relative to the control (A), hypoxia for 24 h relative to the control (B), and hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h relative to the control (C). “O” means “Orthogonal” and “P” means “Predictive” in OPLS-DA. R2X [1] = 0.139, 0.127, 0.094, R2X [2] = 0.125, 0.97, 0.151. Ellipse: Hotelling's T2 (95%).

Table 2 demonstrates that in the hepatopancreas of prawns, as a consequence of 6-h hypoxia, only 13 metabolites were altered (10 were upregulated and three were downregulated). In response to hypoxia for 24 h, the level of 20 metabolites changed significantly in relation to the control (seven were upregulated and 13 were downregulated) (Table 3). The main biochemicals were free amino acids and factors associated with the citrate cycle, glycolysis and redox homeostasis. In response to reoxygenation for 6 h following hypoxia for 24 h, the level of 25 metabolites changed significantly in relation to the control samples (20 were upregulated and five were downregulated) (Table 4). We observed significant changes in energy substrates and cofactors and the biochemicals associated with amino acid metabolism and glutathione synthesis.

Table 2.

Significantly changed metabolites in M. nipponense hepatopancreas between the control group and the 6-h hypoxia group.

| Peak | VIPa | P-valueb | FCc | LOG FCd | Metabolic pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valine | 2.67 | 3.2778E-05 | 3.49 | 1.80 | Amino metabolism |

| Adenine | 1.97 | 0.02 | 0.68 | −0.55 | Amino metabolism |

| Lactic acid | 2.51 | 3.3799E-05 | 2.29 | 1.20 | Energy metabolism |

| Choline | 1.03 | 0.016 | 0.34 | −1.54 | Amino metabolism |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid | 2.14 | 0.006 | 2.12 | 1.09 | Amino metabolism |

| Taurine | 2.26 | 0.005 | 2.16 | 1.11 | Amino metabolism |

| Succinic acid | 2.46 | 0.043 | 0.00002 | −15.672 | Energy metabolism |

| 2-hydroxybutanoic acid | 2.46 | 0.000 | 2.63 | 1.40 | Glutathione synthesis |

| Isoleucine | 2.07 | 0.014 | 1.26 | 0.33 | Energy metabolism |

| Citric acid | 2.34 | 0.000 | 2.06 | 1.04 | Energy metabolism |

| Malic acid | 1.79 | 0.030 | 1.44 | 0.52 | Energy metabolism |

| Alanine | 1.75 | 0.034 | 4.15 | 2.05 | Amino metabolism |

| Leucine | 1.86 | 0.026 | 1.65 | 0.73 | Amino metabolism |

Variable importance in the projection (VIP) was acquired from the OPLS-DA model with a threshold of 1.0.

P-values were calculated from two-tailed Student's t-tests.

FC: fold change between 6-h hypoxia treatment and the control group.

Positive values indicate higher levels in the 6-h hypoxia group than in the control group, negative values indicate lower levels in the 6-h hypoxia group than in the control group.

Table 3.

Significantly changed metabolites in M. nipponense hepatopancreas between the control group and the 24-h hypoxia group.

| Peak | VIPa | P-valueb | FCc | LOG FCd | Metabolic pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valine | 1.44 | 0.01 | 0.26 | −1.94 | Amino metabolism |

| Citrulline 1 | 1.14 | 0.04 | 1.73 | 0.79 | Amino metabolism |

| Cholesterol | 2.53 | 8.2246E-09 | 4.49 | 2.17 | Lipid metabolism |

| Uric acid | 1.78 | 0.01 | 1.73 | 0.79 | Purine metabolism |

| Succinic acid | 2.14 | 0.04 | 2.0812E-05 | −15.55 | Energy metabolism |

| Citric acid | 1.85 | 0.02 | 2.2245E-05 | −15.46 | Energy metabolism |

| Lysine | 2.80 | 2.6343E-06 | 3.1941E-06 | −18.26 | Amino metabolism |

| Linoleic acid | 1.52 | 0.03 | 0.63 | −0.67 | Lipid metabolism |

| Taurine | 2.44 | 0.00 | 2.2863E-05 | −15.42 | Amino metabolism |

| Choline | 1.23 | 0.04 | 0.16 | −2.43 | Amino metabolism |

| Pyruvic acid | 1.38 | 0.01 | 4.11 | 2.04 | Energy metabolism |

| Fumaric acid | 2.21 | 2.3034E-05 | 2.73 | 1.45 | Energy metabolism |

| Malic acid | 1.15 | 0.03 | 0.16 | −2.68 | Energy metabolism |

| Isoleucine | 1.85 | 0.02 | 0.39 | −1.35 | Amino metabolism |

| Lactose | 1.18 | 0.05 | 4.24 | 2.08 | Energy metabolism |

| Alanine | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.29 | −1.76 | Amino metabolism |

| Leucine | 1.22 | 0.01 | 0.45 | −1.15 | Amino metabolism |

| Lactic acid | 2.47 | 0.00 | 11833.791 | 13.53 | Energy metabolism |

| Adenine | 1.45 | 0.00 | 0.23 | −2.13 | Amino metabolism |

| 2-hydroxybutanoic acid | 1.37 | 0.04 | 0.40 | −1.33 | Glutathione synthesis |

Variable importance in the projection (VIP) was acquired from the OPLS-DA model with a threshold of 1.0.

P-values were calculated from two-tailed Student's t-tests.

FC: fold change between 24-h hypoxia treatment and the control group.

Positive values indicate higher levels in the 24-h hypoxia group than in the control group, negative values indicate lower levels in the 24-h hypoxia group than in the control group.

Table 4.

Significantly changed metabolites in M. nipponense hepatopancreas between the control group and the 24-h hypoxia followed by 6-h reoxygenation group.

| Peak | VIPa | P-valueb | FCc | LOG FCd | Metabolic pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 2.20 | 1.6326E-05 | 2.97 | 1.57 | Amino metabolism |

| Sarcosine | 1.76 | 0.01 | 2.39 | 1.26 | Energy metabolism |

| Galactosamine | 2.05 | 0.03 | 3.14 | 1.65 | Glycometabolism |

| Lactic acid | 2.16 | 6.0506E-05 | 2.57 | 1.36 | Energy metabolism |

| Glycine 2 | 1.51 | 0.03 | 0.76 | −0.40 | Amino metabolism |

| Glutamate | 2.14 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 1.05 | Amino metabolism |

| Succinate acid | 1.56 | 0.02 | 1.34 | 0.42 | Energy metabolism |

| Citric acid | 1.67 | 0.01 | 1.56 | 0.64 | Energy metabolism |

| Lysine | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.58 | −0.78 | Amino metabolism |

| Linoleic acid | 1.79 | 0.02 | 2.46 | 1.30 | Lipid metabolism |

| Ribose | 1.42 | 0.02 | 3.17 | 1.66 | Nucleic metabolism |

| Methionine | 1.80 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −3.83 | Amino metabolism |

| Allose | 2.30 | 1.2542E-05 | 1.64 | 0.72 | Glycometabolism |

| N-ethylmaleamic acid | 2.24 | 4.8838E-05 | 1.64 | 0.71 | Glutathione synthesis |

| Allo-inositol | 2.10 | 0.01 | 2906.92 | 11.51 | Glycometabolism |

| Isoleucine | 1.28 | 0.01 | 0.42 | −1.26 | Amino metabolism |

| Leucine | 1.48 | 0.025 | 0.37 | −1.42 | Amino metabolism |

| Glucose | 2.67 | 0.00 | 29830.06 | 14.86 | Energy metabolism |

| Lactone | 1.49 | 0.04 | 574.16 | 9.17 | Energy metabolism |

| Pyroglutamic acid | 1.47 | 0.02 | 3.40 | 1.76 | Glutathione synthesis |

| Fumaric acid | 1.45 | 0.00 | 3.90 | 1.96 | Energy metabolism |

| Malic acid | 1.56 | 0.03 | 2.29 | 1.19 | Energy metabolism |

| Cysteine | 1.60 | 0.01 | 1.43 | 0.52 | Energy metabolism |

| Myo-inositol | 1.73 | 0.02 | 2426.09 | 11.24 | Glycometabolism |

| 2-hydroxybutanoic acid | 1.55 | 0.02 | 1.46 | 0.55 | Glutathione synthesis |

Variable importance in the projection (VIP) was acquired from the OPLS-DA model with a threshold of 1.0.

P-values were calculated from two-tailed Student's t-tests.

FC: fold change between 6-h reoxygenation treatment group and the control group.

Positive values indicate higher levels in the 6-h reoxygenation treatment group than in the control group, negative values indicate lower levels in the 6-h reoxygenation treatment group than in the control group.

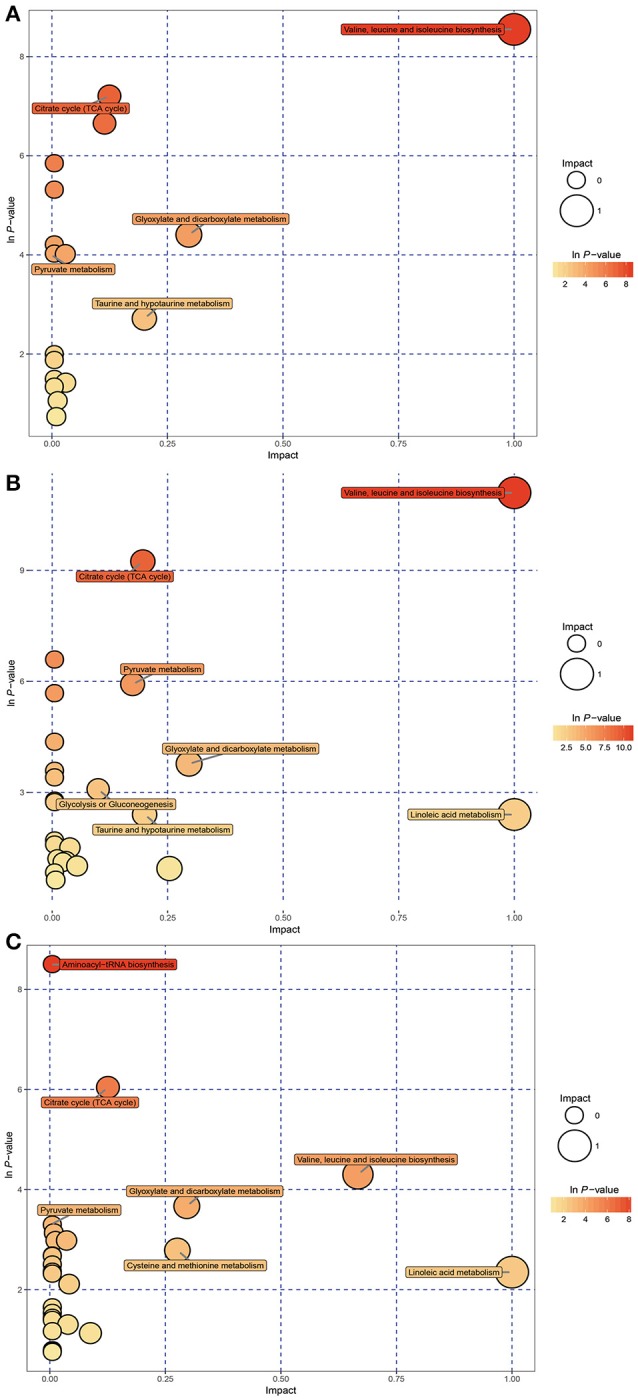

KEGG pathway analysis

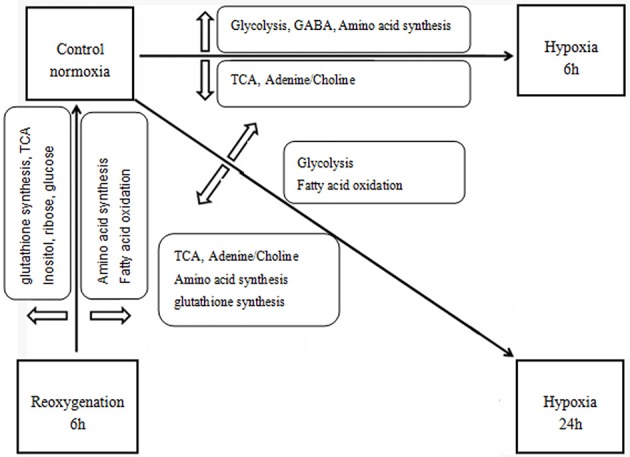

KEGG pathway analysis was performed using Metabo Analyst 3.0 and differentially affected metabolites. Functional pathway analysis revealed the most relevant pathways affected by hypoxic stress included the citrate cycle (TCA cycle), pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis or gluconeogenesis, propanoate metabolism, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, and purine metabolism (Figures 3A,B). The significantly changed pathways identified from affected metabolites in hepatopancreas of prawns after hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h included the TCA cycle, pyruvate metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and linoleic acid metabolism (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Metabolome view map of significant metabolic pathways characterized in hepatopancreas of prawns in response to hypoxia for 6 h (A), hypoxia for 24 h (B), and hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h (C). This figure illustrates significantly changed pathways based on enrichment and topology analysis. Larger sizes and darker colors represent greater pathway enrichment and higher pathway impact values, respectively.

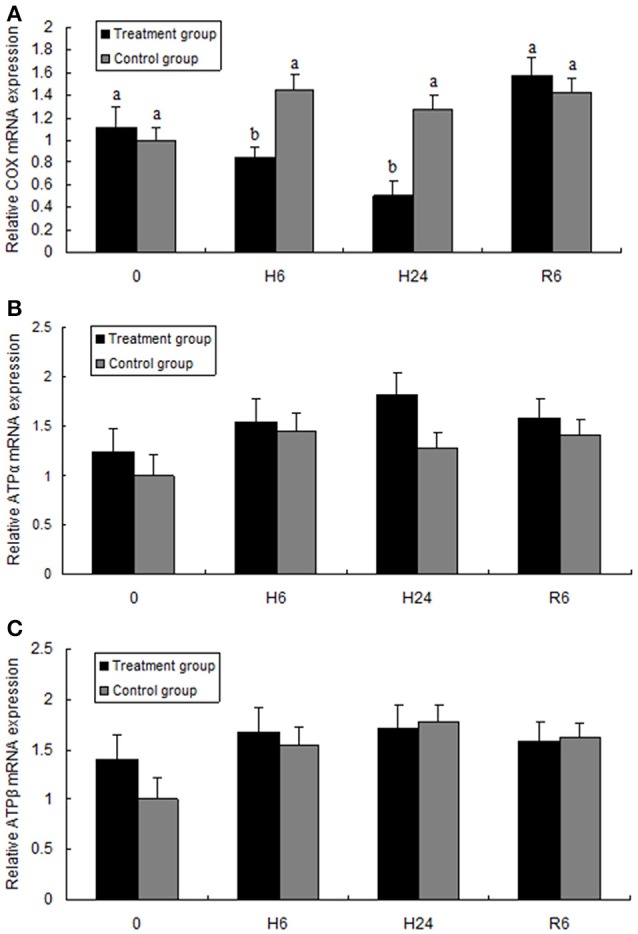

mRNA expression profiles of aerobic metabolism-related genes

Figure 4 shows the expression levels of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COX I) and ATP synthase subunits α and β (ATPα, ATPβ). The expression level of COX I mRNA was significantly lower in the 6- or 24-h hypoxia groups than in the other groups (F = 8.159, P < 0.05). However, after hypoxia followed by reoxygenation for 6 h, the expression level increased to the control levels. The mRNA expression levels of ATPα and ATPβ had no significant change between the control (normoxia) and hypoxia groups, and no significant differences were observed in the expression levels of ATPα and ATPβ between the control (normoxia) and hypoxia–reoxygenation groups.

Figure 4.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of (A) cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COX I), (B) ATP synthase subunit α (ATPα), and (C) ATP synthase subunit β (ATPβ) mRNA expression in the hepatopancreas of juvenile oriental river prawn after exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation. H6 = hypoxia for 6 h, H24 = hypoxia for 24 h, and R6 = hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h. Significant differences (P < 0.05) among all treatment groups are indicated with different letters.

Activities of energy metabolism-related enzymes of M. nipponense in response to hypoxia and reoxygenation

HK, PK, and LDH activities were significantly higher in the hepatopancreas of M. nipponense in the 6- and 24-h hypoxia groups than in the other treatment groups (F = 600.832, P < 0.05; F = 478.105, P < 0.05; F = 741.874, P < 0.05, respectively), but no significant differences were observed in these parameters between the reoxygenation group and the control groups (Figure 5). SDH activity significantly decreased with increase in hypoxia time (F = 76.680, P < 0.05), but SDH activity in the reoxygenated group returned to the levels in the control group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Enzyme activities of hexokinase (HK, A), pyruvate kinase (PK, B), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, C), and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH, D) in the hepatopancreas of juvenile oriental river prawn after exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation. H6 = hypoxia for 6 h, H24 = hypoxia for 24 h, and R6 = hypoxia for 24 h followed by reoxygenation for 6 h. Significant differences (P < 0.05) among all treatment groups are indicated with different letters.

Discussion

Crustaceans often exposed to hypoxia show a complex and highly integrated series of metabolic responses to maintain cellular homeostasis, and ATP synthesis/hydrolysis is crucial in the process of hypoxia-induced stress.

Compared with hypoxia sensitive M. nipponense, the survival of penaeid shrimp is not greatly affected by long-term moderate hypoxia, as reported for Pacific whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Racotta et al., 2002), thus, we compared the mRNA expression levels of electron transport chain-related enzymes between M. nipponense and L. vannamei. First, we consider aerobic metabolism. The mitochondrial FOF1 ATP-synthase complex catalyzes ATP synthesis (Pedersen, 2007) via chemiosmotic coupling to the respiratory chain. We observed no significant changes in ATPα and ATPβ mRNA expression in prawns during hypoxia or subsequent reoxygenation; this is not consistent with previous findings in the L. vannamei (Martinez-Cruz et al., 2011) where mRNA level of ATPβ increased in response to hypoxia and a subsequent decreased when L. vannamei were re-oxygenated. A reasonable explanation is that prawns starts to use anaerobic metabolism during acute hypoxia, so it might not need to synthesize more new ATP-synthase complexes. The respiratory chain complex II (SDH) is the only enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) in the inner mitochondrial membrane, and SDH activity reflects the level of aerobic metabolism (Gao et al., 2016). Similarly with previous study in M. nipponense (Guan et al., 2010), the present results showed that significantly lower SDH activity was found in the M. nipponense exposed to hypoxia, indicating a lower level of aerobic metabolism in these animals. Inhibition of the mRNA expression of respiratory chain complex IV (COX), which we observed here in the hypoxic samples (Jimenez-Gutierrez et al., 2013, 2014), can affect the respiratory function of mitochondria, leading to cell hypoxia or death (Reiffienstcin et al., 1992). Finally, an increase in the beta-hydroxybutyric acid concentration was observed in all hypoxic groups; this probably reflects cessation of ketone-body metabolism as the TCA cycle is not functioning during hypoxia (Mimura and Furuya, 1995). Collectively, our data suggest a hypoxia-associated general inhibition of aerobic energy metabolism in M. nipponense.

In the present study, glycolysis-related enzyme activities of M. nipponense (HK, PK, and LDH) were significantly increased by hypoxia for 6 and 24 h compared with the control group, which was similar to the findings in a previous study of the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Soñanez-Organis et al., 2011, 2012; Cota-Ruiz et al., 2015). These findings suggest that hypoxia results in a shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, and that sufficient ATP can be generated only by upregulating oxygen-independent mechanisms in hypoxic crustacea. Eventually, glucose/glycogen become exhausted and metabolic waste products such as lactate accumulate, as was also shown in our present study. Acute hypoxia caused a significant increase in the lactate concentration in the hepatopancreas extracts. Interestingly, reoxygenation treatment resulted in a higher lactate content in the hepatopancreas compared to the normoxia group; this indicates the presence of a Warburg effect-like response, as has been reported in other crustacean species (Su et al., 2014). In hypoxia, a sufficient and possibly augmented supply of glucose is required because anaerobic glycolysis is increased to obtain sufficient energy.

Levels of branched-chain amino acids including valine, isoleucine, leucine, decreased in hepatopancreas samples under 24-h hypoxia (relative to the normoxic controls), and branched-chain amino acids were still present at a lower level in prawns that were exposed to hypoxia for 24 then reoxygenated for 6 h. These essential amino acids contribute to global regulation of growth and metabolism (Wang et al., 2011). For example, a decreased concentration of isoleucine in the hepatopancreas was observed in a previous study of hypoxia in prawns and was possibly due to difficulty in taking up food because of the hypoxia (Ren et al., 2014), suggesting that hypoxia can suppress feeding behavior of prawns to some extent. Lysine is an essential amino acid for protein synthesis and a ketogenic amino acid (Sauer et al., 2015); the concentration of lysine was significantly decreased in prawns in response to hypoxia compared to the control group, suggesting that protein degradation was likely to be higher in the hypoxia group than in the control group. This could partly explain the slower growth trend of shrimp under hypoxic stress (Duan et al., 2013). The protective effect of taurine during acute hypoxia in mammalian tissues has recently been reported (Michalk et al., 1997). Prawns in the 24-h hypoxia group also had lower taurine and 2-hydroxybutanoic acid levels than the control group prawns; this was correlated with the synthesis of glutathione, a well-known antioxidant. This could explain why in previous studies, L. vannamei under hypoxic group showed higher antioxidant ability than that of the normoxic group (Parrilla-Taylor and Zenteno-Savín, 2011; Li et al., 2016).

Choline is the precursor of the osmolyte betaine, and is a substrate in the choline kinase-catalyzed conversion of ATP to phosphocholine and ADP. Here, the choline and betaine contents decreased in the hepatopancreas after hypoxic stress, suggesting that hypoxia may affect molecular pathways of the methionine cycle (Bertolo and McBreairty, 2013). Similar to the results of the present study, a higher flux toward the methionine cycle after environmental stress was demonstrated for gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata (Richard et al., 2016), the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum (Zhang et al., 2017), and rainbow smelt Osmerus mordax (Richards and Short, 2010). Choline and betaine are among several methyl-donors in the methionine cycle. Methionine plays an important role in protecting cells against reactive oxygen species (ROS) by neutralizing free radicals (Alirezaei et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014). A previous study in our laboratory showed that hypoxia-induced H2O2 and ROS levels (Sun et al., 2017) and apoptosis were increased in hemocytes following hypoxia, presumably due to increased ROS production (Sun et al., 2016b). Taken together, the findings suggest that hypoxia leads to oxidative stress (Chen et al., 2017).

Thus, lower choline and betaine concentrations in M. nipponense in response to hypoxia may explain why M. nipponense is a hypoxia-sensitive prawn. Furthermore, higher pyroglutamic acid and n-ethylmaleamic acid levels were observed in the hepatopancreas of M. nipponense after hypoxia then reoxygenation for 6 h; these molecules are precursors in glutathione synthesis in the hepatopancreas of crustaceans (Niedzwiecka et al., 2011), which supports the hypothesis that antioxidant synthesis in the hepatopancreas occurs in prawns to help alleviate oxidative stress during recovery from hypoxia.

The significantly affected metabolites and pathways in the metabolic response of prawns to hypoxia and reoxygenation are shown in Figures 4, 6. According to the metabolic pathway analysis, a few very important pathways present distinct differences in the control vs. 6-h hypoxia groups and the control vs. 24-h hypoxia groups. For example, the valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis and linoleic acid metabolism pathways are the key different metabolic pathways involved in energy supply. These results further reiterate that hypoxic prawns make use of amino acids and fatty acid metabolism to supply energy, with lower efficiency than aerobic metabolism.

Figure 6.

Schematic overview of the metabolic changes in the hepatopancreas of juvenile oriental river prawn in response to hypoxia (6 or 24 h) and subsequent 6-h reoxygenation. Metabolite TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; NAA, N-acetylaspartate, GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid.

In summary, hypoxia has a significant effect on antioxidant defense factors as well as energy metabolism. These findings indicate that M. nipponense can be a sensitive bioindicator of hypoxic stress.

Author contributions

SS, ZBG, and HF: Conceived and designed the experiments; SS, ZBG, JZ, and ZMG: Carried out the experiments and analyzed the data; SS, HF, and XG: Supervised the project; SS: Wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31672633), the China Central Governmental Research Institutional Basic Special Research Project from Public Welfare Fund (Grant No. 2017JBFM02), the National Science & Technology Supporting Program of the 12th Five-year Plan of China (Grant No. 2012BAD26B04), the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (Grant No. 201303056-6), the Science & Technology Supporting Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BE2012334), and the Three New Projects of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. D2013-6).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00076/full#supplementary-material

Representative gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) total ion chromatograms from oriental river prawn (M. nipponense) hepatopancreas samples obtained from the control group (black), 6-h hypoxia treatment group (red), 24-h hypoxia group (blue), and the 24-h hypoxia followed by 6-h reoxygenation group (green).

References

- Alirezaei M., Reza G. H., Reza R. V., Hajibemani A. (2012). Betaine: a promising antioxidant agent for enhancement of broiler meat quality. Br. Poult. Sci. 53, 699–707. 10.1080/00071668.2012.728283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. W., Eggleston D. B. (2005). Species-specific avoidance responses by blue crabs and fish to chronic and episodic hypoxia. Mar. Biol. 146, 761–770. 10.1007/s00227-004-1483-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolo R. F., McBreairty L. E. (2013). The nutritional burden of methylation reactions. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 16, 102–108. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835ad2ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Peterson N. J., Manning C., Patel V., Denslow N., Brouwer M. (2008). Effects of cyclic hypoxia on gene expression and reproduction in a grass shrimp, Palaemonetes pugio. Biol. Bull. 214, 6–16. 10.2307/25066655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Peterson N. J., Manning C. S., Denslow N. D., Brouwer M. (2011). Impacts of cyclic hypoxia on reproductive and gene expression patterns in the grass shrimp: field versus laboratory comparison. Aquat. Sci. 73, 127–141. 10.1007/s00027-010-0166-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Wu M., Tang G. P., Wang H. J., Huang C. X., Wu X. J. (2017). Effects of acute hypoxia and reoxygenation on physiological and immune responses and redox balance of Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala Yih, 1955). Front. Physiol. 8:375. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Ruiz K., Peregrino-Uriarte A. B., Felix-Portillo M., Martínez-Quintana J. A., Yepiz-Plascencia G. (2015). Expression of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase and phosphofructokinase is induced in hepatopancreas of the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei by hypoxia. Mar. Environ. Res. 106, 1–9. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig J. K., Crowder L. B., Henwood T. A. (2005). Spatial distribution of brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztecus) on the northwestern Gulf of Mexico shelf: effects of abundance and hypoxia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 62, 1295–1308. 10.1139/f05-036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y., Zhang X. M., Zhang Z. X. (2013). The effect of dissolve oxygen concentration on the growth and digestive enzyme activity of whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. J. Ocean. U. China 43, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. B., Zhang M., Li X. N., Shi C., Song C. B., Liu Y. (2016). Effects of LED light quality on the growth, metabolism, and energy budgets of Haliotis discus discus. Aquaculture 453, 31–39. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.11.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y. Q., Li L. I., Wang H. C., Wang Z. L. (2010). Effects of hypoxia on respiratory metabolism and antioxidant capability of Macrobrachium nipponense. J. Hebei. Uni. 30, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman T. M., Rojas-Vargas A. C., Jones D. R., Richards J. G. (2008). Differential recovery from exercise and hypoxia exposure measured using (31)P- and (1)H-NMR in white muscle of the common carp Cyprinus carpio. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3237–3248. 10.1242/jeb.019257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug K., Salek R. M., Conesa P., Hastings J., De Matos P., Rijnbeek M., et al. (2013). MetaboLights–an open-access general-purpose repository for metabolomics studies and associated meta-data. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D781–D786. 10.1093/nar/gks1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines A., Oldiran G. S., Bignell J. P., Stentiford G. D., Viant M. (2007). Direct sampling of organisms from the field and knowledge of their phenotype: key recommendations for environmental metabolomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 3375–3381. 10.1021/es062745w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Li F. H., Xie Y. S., Huang B. X., Zhang J. K., Zhang J. Q., et al. (2009). Comparative proteomic profiles of the hepatopancreas in Fenneropenaeus chinensis response to hypoxic stress. Proteomics 9, 3353–3367. 10.1002/pmic.200800518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gutierrez L. R., Hernandez-Lopez J., Islas-Osuna M. A., Muhlia-Almazan A. (2013). Three nucleus-encoded subunits of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase of the whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: cDNA characterization, phylogeny and mRNA expression during hypoxia and reoxygenation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 166, 30–39. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gutierrez L. R., Uribe-Carvajal S., Sanchez-Paz A., Chimeo C., Muhlia-Almazan A. (2014). The cytochrome c oxidase and its mitochondrial function in the whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei during hypoxia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 46, 189–196. 10.1007/s10863-013-9537-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T., Wohlgemuth G., Lee D. Y., Lu Y., Palazoglu M., Shahbaz S., et al. (2009). FiehnLib: mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics basedon quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81, 10038–10048. 10.1021/ac9019522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniffin C. D., Burnett L. E., Burnett K. G. (2014). Recovery from hypoxia and hypercapnic hypoxia: impacts on the transcription of key antioxidants in the shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 170, 43–49. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardon I., Eyckmans M., Vu T. N., Laukens K., Boeck G. D., Dommisse R., et al. (2013a). 1H-NMR study of the metabolome of a moderately hypoxia tolerant fish, the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Metabolomics 9, 1216–1227. 10.1007/s11306-013-0540-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lardon I., Nilsson G. E., Stecyk J. A. W., Vu N. T., Laukens K., Dommisse R., et al. (2013b). 1H-NMR study of the metabolome of an exceptionally anoxia tolerant vertebrate, the crucian carp (Carassius carassius). Metabolomics 9, 311–323. 10.1007/s11306-012-0448-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. D., Brouwer M. (2009). Gene expression profile of grass shrimp Palaemonetes pugio exposed to chronic hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 4, 196–208. 10.1016/j.cbd.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. D., Brouwer M. (2013). Gene expression profile of hepatopancreas from grass shrimp Palaemonetes pugio exposed to cyclic hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 8, 1–10. 10.1016/j.cbd.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. Y., Li E. C., Suo Y. T., Xu Z. X., Jia Y. Y., Qin J. G., et al. (2017). Energy metabolism and metabolomics response of Pacific whiteshrimp Litopenaeus vannamei to sulfide toxicity. Aquat. Toxicol. 183, 28–37. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wei L., Cao J., Qiu L., Jiang X., Li P., et al. (2016). Oxidative stress, DNA damage and antioxidant enzyme activities in the pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) when exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Chemosphere 144, 234–240. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Sun H., Wang Y., Ma M., Zhang Y. (2014). Gender-specific metabolic responses in hepatopancreas of mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis challenged by Vibrio harveyi. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 40, 407–413. 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 5, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B., Groenke K., Takors R., Wandrey C., Oldiges M. (2007). Simultaneous determination of multiple intracellular metabolites in glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1147, 153–164. 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K., Feng J., Lin J., Li J. (2011). The complete mitochondrial genome of Macrobrachium nipponense. Gene 487, 160–165. 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum C. P. (1997). Adaptation of the oxygen transport system to hypoxia in the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. Am. Zool. 37, 604–611. 10.1093/icb/37.6.604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum C. P., Rainer J. S. (1988). The relationship between subunit composition and O2 binding of blue crab hemocyanin. Biol. Bull. 174, 77–82. 10.2307/1541761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Cruz O., Garcia-Carreño F., Robles-Romo A., Varela-Romero A., Muhlia-Almazan A. (2011). Catalytic subunits atpα and atpβ from the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei FOF1 ATP-synthase complex: cDNA sequences, phylogenies, and mRNA quantification during hypoxia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 43, 119–133. 10.1007/s10863-011-9340-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalk D. V., Wingenfeld P., Licht C. (1997). Protection against cell damage due to hypoxia and reoxygenation: the role of taurine and the involved mechanisms. Amino. Acids. 13, 337–346. 10.1007/BF01372597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura Y., Furuya K. (1995). Mechanisms of adaptation to hypoxia in energy metabolism in rats. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 181, 437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiecka N., Mika A., Białk-Bielinska A., Stepnowski P., Skorkowski E. F. (2011). Effect of cadmium and glutathione on malic enzyme activity in brown shrimps (Crangon crangon) from the Gulf of Gda'nsk. Oceanologia 53, 793–805. 10.5697/oc.53-3.793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nudi A. H., Angela W., Scofield D. E. (2008). PAH metabolites in urine of crab ucides cordatus by HPLC/fluorescence detection. Mar. Environ. Res. 66, 187–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo L., Villarreal H., Vargas M., Portillo G., Magallon F. (2000). Effects of dissolved oxygen and temperature on growth, survival and body composition of juvenile Farfantepenaeus californiensis (Holmes). Aquac. Res. 31, 167–171. 10.1046/j.1365-2109.2000.00405.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla-Taylor D. P., Zenteno-Savín T. (2011). Antioxidant enzyme activities in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in response to environmental hypoxia and reoxygenation. Aquaculture 318, 379–383. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. (2007). Transport ATPases into the year 2008: a brief overview related to types, structures, functions and roles in health and diseas. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 39, 349–355. 10.1007/s10863-007-9123-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Xiong Y. W., Zhang W. Y., Fu H. G., Jiang S. F., Sun S. M., et al. (2015). Characterization, expression, and function analysis of gonad-inhibiting hormone in Oriental River prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense and its induced expression by temperature. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Comp. Physiol. 185, 1–8. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu R. J., Cheng Y. X., Huang X. X., Wu X. G., Yang X. Z., Tong R. (2011). Effect of hypoxia on immunological, physiological response, and hepatopancreatic metabolism of juvenile Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Aquac. Int. 19, 283–299. 10.1007/s10499-010-9390-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Racotta I. S., Palacios E., Mendez L. (2002). Metabolic responses to short and long-term exposure to hypoxia in white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Mar. Fresh. Behav. Physiol. 35, 269–275. 10.1080/1023624021000019333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffienstcin R. J., Hullbert W. C., Roth S. H. (1992). Toxicity of hydrogen sulfied. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 32, 109–134. 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.000545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W. K., Yin J., Gao W., Chen S., Duan J. L., Liu G., et al. (2015). Metabolomics study of metabolic variations in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-infected piglets. RSC Adv. 5:59550–59555. 10.1039/C5RA09513A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W., Yin J., Duan J., Liu G., Zhu X., Chen S., et al. (2014). Mouse jejunum innate immune responses altered by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) infection. Microbes Infect. 16, 954–961. 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard N., Silva T. S., Tune W., Schrama D., Dias J. P., Rodrigues P. M., et al. (2016). Nutritional mitigation of winter thermal stress in gilthead seabream: associated metabolic pathways and potential indicators of nutritional state. J. Proteome. 142, 1–14. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards R. C., Short C. E. (2010). Seasonal changes in hepatic gene expression reveal modulation of multiple processes in rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax). Mar. Biotechnol. 12, 650–663. 10.1007/s10126-009-9252-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Z., Lv Y. F., Fu X. F., He Q. H., Deng Z. Y., Liu W. Q., et al. (2013). Metabolomic analysis of amino acid metabolism in colitic rats supplemented with lactosucrose. Amino. Acids. 45, 877–887. 10.1007/s00726-013-1535-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer S. W., Opp S., Komatsuzaki S., Blank A. E., Mittelbronn M., Burgard P., et al. (2015). Multifactorial modulation of susceptibility to llysine in an animal model of glutaric aciduria type I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1852, 768–777. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., Li C. H., Chen X. C., Zhang P. J., Li Y., Li T. W., et al. (2015). Metabolomic responses of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus to thermal stresses. Aquaculture 435, 390–397. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.10.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soñanez-Organis J. G., Peregrino-Uriarte A. B., Sotelo-Mundo R. R., Forman H. J., Yepiz-Plascencia G. (2011). Hexokinase from the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: cDNA sequence, structural protein model and regulation via HIF-1 in response to hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 158, 242–249. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soñanez-Organis J. G., Rodriguez-Armenta M., Leal-Rubio B., Peregrino-Uriarte A. B., Yepiz-Plascencia G. (2012). Alternative splicing generates two lactate dehydrogenase subunits differentially expressed during hypoxia via HIF-1 in the shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Biochimie 94, 1250–1260. 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Zhou H., Han Q., Diao X. (2017). Toxic responses of Perna viridis hepatopancreas exposed to DDT, benzo(a)pyrene and their mixture uncovered by iTRAQ-based proteomics and NMR-based metabolomics. Aquat. Toxicol. 192, 48–57. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Xu H., Sun N., Jiang L., Tian P., Yong Y., et al. (2017). Metabolomic analysis of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) root-symbiotic rhizobia responses under alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1208. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. D., Tibshirani R. (2003). Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9440–9445. 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M. A., Huang Y. T., Chen I. T., Lee D. Y., Hsieh Y. C., Li C. Y., et al. (2014). An invertebrate Warburg effect: a shrimp virus achieves successful replication by altering the host metabolome via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004196. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. M., Xuan F. J., Fu H. T., Ge X. P., Zhu J., Qiao H., et al. (2016a). Molecular characterization and mRNA expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1 and cognate inhibiting factor in Macrobrachium nipponense in response to hypoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 196–197, 48–56. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. M., Xuan F. J., Fu H. T., Ge X. P., Zhu J., Qiao H., et al. (2016b). Comparative proteomic study of the response to hypoxia in themuscle of oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). J. Proteomics 138, 115–123. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. M., Xuan F. J., Fu H. T., Zhu J., Ge X. P., Gu Z. M. (2015). Transciptomic and histological analysis of hepatopancreas, muscle and gill tissues of oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense) in response to chronic hypoxia. BMC Genomics 16:491. 10.1186/s12864-015-1701-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. M., Xuan F. J., Fu H. T., Zhu J., Ge X. P., Wu X. G. (2017). Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of caspase-3 from the oriental river prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense when exposed to acute hypoxia and reoxygenation. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 62, 291–302. 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. M., Xuan F. J., Ge X. P., Fu H. T., Zhu J., Zhang S. Y. (2014). Identification of differentially expressed genes in hepatopancreas of oriental river prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense exposed to environmental hypoxia. Gene 534, 298–306. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffnail W., Mills G. A., Cary P., Greenwood R. (2009). An environmental 1H NMR metabolomic study of the exposure of the marine mussel Mytilus edulis to atrazine, lindane, hypoxia and starvation. Metabolomics 5, 33–43. 10.1007/s11306-008-0143-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yan B., Liu N., Li Y., Wang Q. (2008). Effects of cadmium on glutathione synthesis in hepatopancreas of freshwater crab, Sinopotamon yangtsekiense. Chemosphere 74, 51–56. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Haipeng S., Lu G., Ren S., Chen J. (2011). Catabolism of branched-chain amino acids in heart failure: insights from genetic models. Pediatr. Cardiol. 32, 305–310. 10.1007/s00246-010-9856-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Jiang W. D., Liu Y., Chen G. F., Jiang J., Li S. H., et al. (2014). Effect of choline on antioxidant defenses and gene expressions of Nrf2 signaling molecule in the spleen and head kidney of juvenile Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian). Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 38, 374–382. 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R. S. (2002). Hypoxia: from molecular responses to ecosystem responses. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 45, 35–45. 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00061-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wu H. F., Wei L., Xie Z. P., Guan B. (2017). Effects of hypoxia in the gills of the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum using NMR-based metabolomics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 114, 84–89. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Representative gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) total ion chromatograms from oriental river prawn (M. nipponense) hepatopancreas samples obtained from the control group (black), 6-h hypoxia treatment group (red), 24-h hypoxia group (blue), and the 24-h hypoxia followed by 6-h reoxygenation group (green).