Abstract

Glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) transactivation reporter gene assays were used as an initial high-throughput screening on a diversified library of 1200 compounds for their evaluation as GCR antagonists. A class of imidazo[2,1-b]benzothiazole and imidazo[2,1-b]benzoimidazole derivatives were identified for their ability to modulate GCR transactivation and anti-inflammatory transrepression effects utilizing GCR and NF-κB specific reporter gene assays. Modeling studies on the crystallographic structure of the GCR ligand binding domain provided three new analogues bearing the tetrahydroimidazo[2,1-b]benzothiazole scaffold able to antagonize the GCR in the presence of dexamethasone (DEX) and also defined their putative binding into the GCR structure. Both mRNA level measures of GCR itself and its target gene GILZ, on cells treated with the new analogues, showed a GCR transactivation inhibition, thus suggesting a potential allosteric inhibition of the GCR.

Keywords: Imidazo[2,1-b]benzothiazole; imidazo[2,1-b]benzoimidazole; GCR allosteric inhibition; anti-inflammatory GCR like activity; reduced GILZ expression

Cortisol is synthesized in the adrenal glands but is also regenerated mainly in the liver from inactive cortisone by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1. Natural and synthetic glucorticoids are the ligands of the glucocorticoid receptor (GCR), which belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. GCR has a dual mode of action: “transactivation” as a ligand-activated transcription factor that binds to glucocorticoid response elements located in the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and as a modulator (often trans-repressor) of other transcription factors such as NF-kB.1−3 The final resulting physiological action is the regulation/maintenance of basal and stress-related homeostasis.4

Glucocorticoids are the most prescribed drugs for anti-inflammatory purposes, but their continued use is restricted by serious side effects: hypertension and major metabolic side effects such as glucose intolerance, muscle wasting, skin thinning, and osteoporosis. Therefore, in order to avoid such side effects, GCR signaling pathways have been the focus of intensive research to find modulators active either on transactivation or transrepression.5−7

Selective GCR antagonists have been the interest of active chemistry in the last two decades. Their potential therapeutic applications are very broad, including Cushing’s syndrome, psychotic depression, diabetes, obesity, Alzheimer’s disease, neuropathic pain, drug abuse, and glaucoma.8 Depending on the chemical structure, they can be classified as (1) steroidal, such as the nonselective GCR antagonist RU-486 (mifepristone), which was used for the treatment of Cushing’s syndrome9 and the GCR-selective steroid RU-4304410 and (2) nonsteroidal GCR antagonists including octahydrophenanthrenes, spirocyclic dihydropyridines, triphenylmethanes and diaryl ethers, chromenes, dibenzyl anilines, dihydroisoquinolines, pyrimidinediones, azadecalins, aryl pyrazolo azadecalins, quinolin-3-one, and polyhydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls.8,11−14

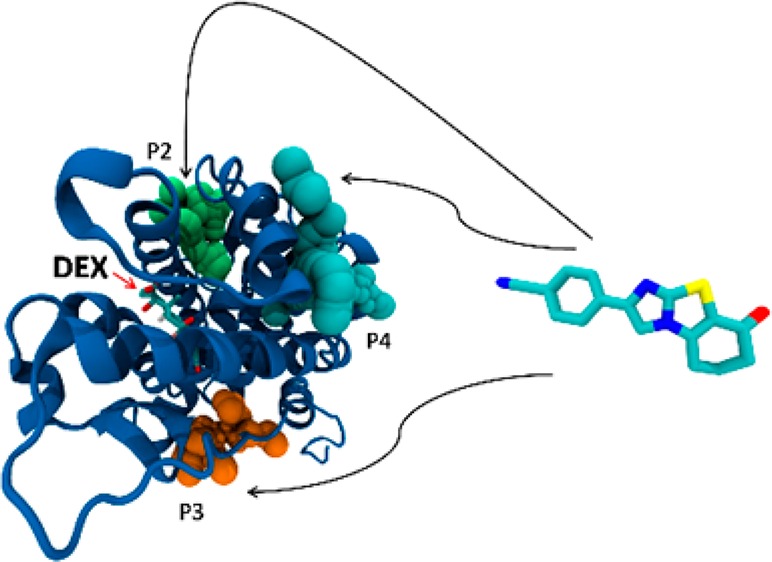

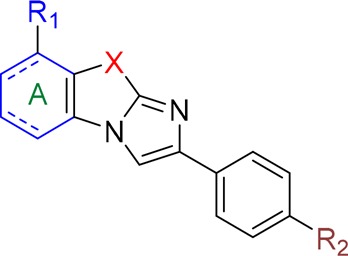

Herein, by screening a library of 1200 compounds using GCR competition binding assays, a new moiety bearing the imidazo[2,1-b]benzothiazole and imidazo[2,1-b]benzoimidazole skeleton was identified as a new scaffold for the inhibition of the GCR activity (Figure 1). Modeling studies of the most active compound on the crystallographic structure of the GCR ligand binding domain provided three novel structures, which were synthesized and further evaluated for their antagonist action mechanism against GCR in the presence of DEX15 (Figure 1). Allosteric binding and inhibition of inflammatory activity were the two main suggested features for our compounds.

Figure 1.

General structure of the hit compounds and of DEX.

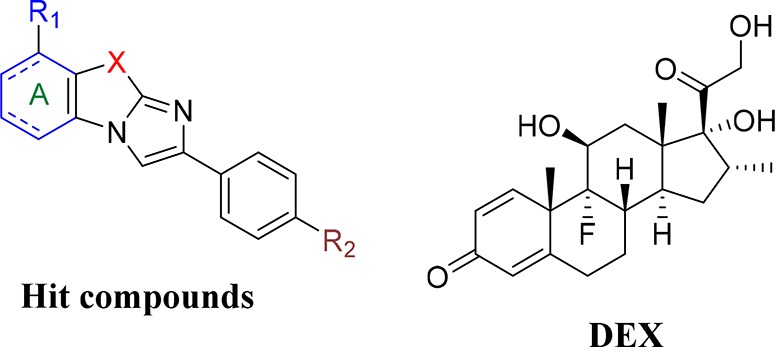

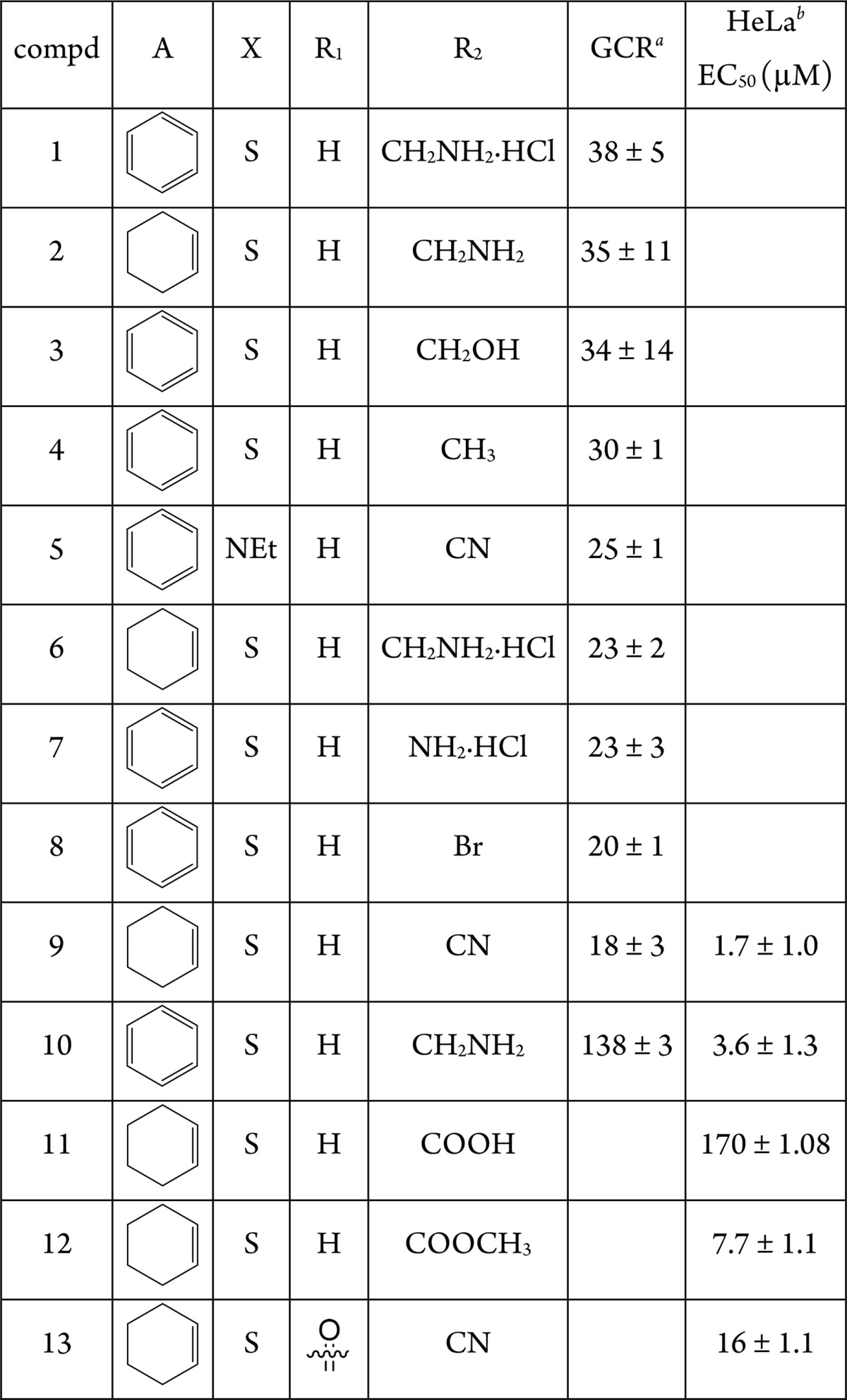

First, GCR luciferase reporter gene assay was performed following single compound treatment (0.1 μM) to compare potential agonistic compound effects relative to the reference agonistic compound DEX (1 μM). However, none of the tested compounds induced GCR agonistic effects (Figure S1). Next, to evaluate antagonistic effects, we performed a GRE luc reporter gene assay following single compound combination treatments with DEX (1 μM). As it can be observed from Table 1, DEX induced GCR transactivation can be reversed by compounds 1–9, with compound 9 being the most potent, reducing DEX induced GCR transactivation by 82% (100% is DEX effect). In contrast, a compound with a similar structure, 10, was found to be completely ineffective (Table 1, Figure S2). The increased effect of the hydrochloric salts 1 and 6, in comparison to the parent compounds 10 and 2, can be explained by the higher water solubility.

Table 1. GCR Antagonistic Effects in Comparison to DEX Effects Taken as 100%.

Modulation in %.

The data are reported as means ± SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

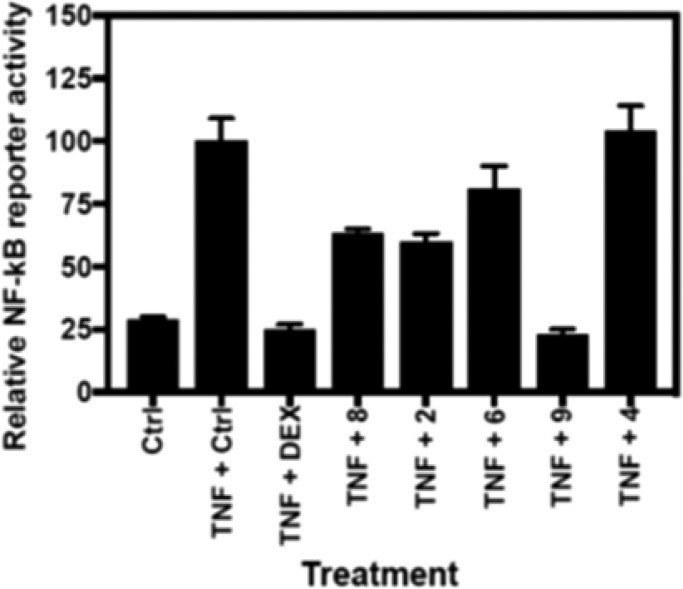

Complementary to the GCR reporter screening, the most active compounds identified in the GCR reporter assay were also tested for their possible anti-inflammatory GCR transrepression effects in a complementary NF-kB reporter assay. Compounds were evaluated for their potency to suppress TNF induced NF-kB reporter activity upon 4 h combination treatment following 2 h pretreatment with the single compound. Interestingly, various degrees of NF-kB inhibition were observed, with compound 9 being the most bioactive, reducing TNF induced NF-kB activation by approximately 76% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Suppression of TNF induced NF-kB reporter activity in the presence of tested compounds.

It is known that molecular docking studies on biological systems can predict the structures of intermolecular complexes formed by ligands and their receptors.16 In a number of different systems, molecular docking has been employed to rationalize experimental results for a great variety of targets, such as proteins,17−19 enzymes,20−23 and DNA.24−26 The technique can predict intermolecular receptor–ligand structures not easily accessible through experiments. Moreover, molecular docking can provide atomic level information about the interactions occurring within the binding site and in the putative ligand-binding “pockets” found in a protein.

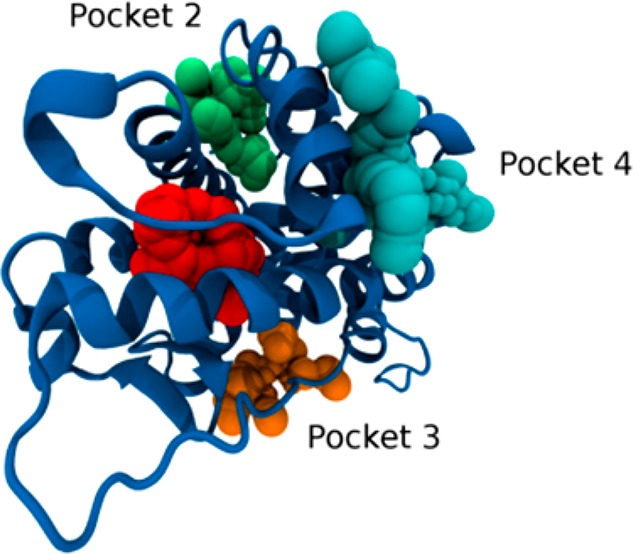

Here, the crystallographic structure of the GCR ligand binding domain revealed 14 such different pockets, whose volume, depth, and polarity are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. A molecular docking calculation was carried out for the most antagonistic compound, 9, in every pocket of the GCR (Table S2). The most interesting pockets, from the geometric, energetic, and chemical points of view, were found to be pockets 2, 3, and 4. In these pockets, indeed, we noticed a high density of hydrogen bond donor residues (Table S3). This common feature of the three pockets led us to the design of three new compounds: 11, 12, and 13 (Table 1). These molecules share the same scaffold with compound 9 but have different R1 and R2 substituents. In particular, we added hydrogen bond acceptor functional groups, such as carboxyl, ester, and carbonyl group, in order to improve the binding in pockets 2, 3, and 4, exploiting the high density of hydrogen bond donor residues. These new compounds were docked in all the 14 pockets identified by the former analysis in order to compare their binding poses and energy (Table S2). Interestingly, compounds 11, 12, and 13 always displayed a lower binding energy compared to 9, in particular in pockets 2, 3, and 4.

The binding site of DEX (pocket 0) showed the largest volume and the lowest binding energy with respect to the other pockets confirming that, in the absence of DEX, the studied compounds would bind in this pocket but with a lower affinity comparing to DEX. The docked conformation of the modeled compounds displayed the lowest energy values in pockets 2, 3, and 4 highlighted in Figure 3, where the compounds are shown as being able to bind even in the presence of DEX. We carried out an analysis of chemical interactions in the selected pockets. All the docked structures in pocket 2 adopt the same binding mode. The carboxyl and the ester of compounds 11 and 12 are oriented toward His 726, Tyr 764, and Ser 674, with the two oxygens forming hydrogen bonds (HBs) with the aforementioned residues (Figure S3). The nitrile substituents of compounds 9 and 13 form a HB with His 726 (Figure S4). The docking poses of the same compounds within pocket 3 are, also, very similar. We observed a salt bridge between the carboxyl group of compound 11 and Arg 614, and a HB between the acceptor nitrogen of all scaffolds and Tyr 663 (Figure S5). Within pocket 4, compound 9 exhibited a different docking pose compared to 11, 12, and 13. In particular, there is a salt bridge between the carboxyl group of 11 and Arg 585, and a HB between both the carbonyl groups of 11 and 12 and Gln 592. The carbonyl group of compound 13 makes a HB with Met 752 (Figure S6). The nitrile group of 9 is oriented toward the same direction, but the docking pose of the rigid scaffold differs from 11, 12, and 13 (Figure S7). These three compounds were designed in such a way as to interact with HB donor residues in the selected pockets (Table S3), providing additional interactions compared to compound 9. Finally, all the modified compounds display a lower binding energy in the selected pockets with respect to compound 9.

Figure 3.

Three putative binding sites in the ligand binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor for compounds 11, 12, and 13: in green, pocket 2; in cyan, pocket 4; in orange, pocket 3; in red, the binding site of DEX.

In the next step, the proposed compounds 11–13 were tested for their GCR antagonist activity. The results presented in Supporting Information Figure S8 show that, unlike RU486, which competitively inhibits GCR activity, the compounds 11–13 are not classic competitive inhibitors of the GCR activity since they do not compete with DEX.

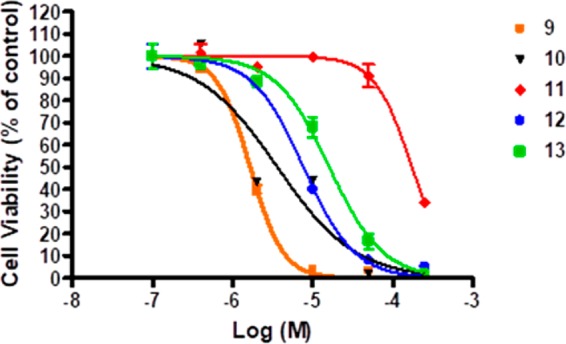

Since our compounds showed non-competitive antagonism against DEX, we evaluated the cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells of the most active compounds 9 and 11–13; compound 10 was our negative control since it showed very low activity in terms of binding to the GCR (Table 1). The cytotoxicity of derivatives 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 for HeLa cells was studied with the MTT test, after 72 h of cell exposure in complete medium. Data presented in Table 1 and Figure 4 show that all the compounds induced a cytotoxic effect with an EC50 (μM) of 1.7, 3.6, 170, 7.7, and 16 for compounds 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13, respectively. In terms of cytotoxicity for HeLa cells, these results demonstrate a pronounced difference in the behavior of the 9 and 10 derivatives and 11, 12, and 13 compounds tested. Further analysis was therefore focused on the less toxic compounds 11, 12, and 13 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of compounds 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 in HeLa cells. Cells were exposed for 72 h to the compounds at different concentrations (0.4, 2, 10, 50, and 250 μM), and cytotoxicity was evaluated by the MTT assay. The data are reported as means ± SE of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

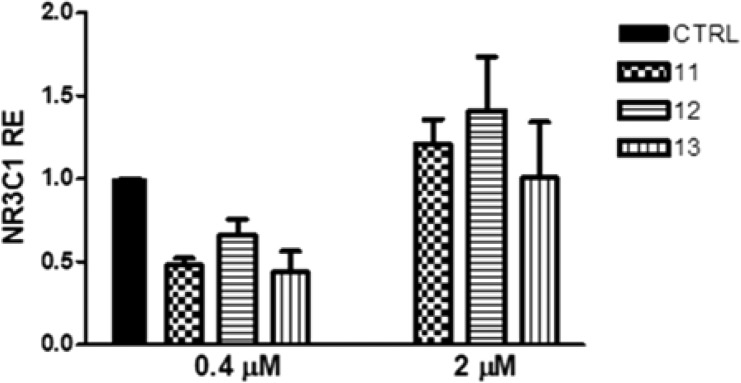

To investigate the mechanism of the non-competitive antagonism found, the effect of compounds 11, 12, and 13 on GCR expression was evaluated. GCR transcripts were quantified in HeLa cells treated for 24 h at 0.4 and 2 μM with the three compounds. Interestingly, the treatment with the compounds at 0.4 μM induced a downregulation of the GCR (about 50% for compound 11), but not at 2 μM (Figure 5). The presence of this effect only at lower concentration could be related to cytotoxic effects at higher concentration. The effect on GCR expression of compounds 9 and 10 was also evaluated (Figure S9), highlighting that the least cytotoxic compound (9) is more similar to compounds 11–13 than compound 10.

Figure 5.

GCR expression in HeLa cells after treatment with compounds 11, 12, and 13 for 24 h at 0.4 and 2 μM. One-way ANOVA; 0.4 μM, p = 0.057; 2 μM, p = 0.92. The data are reported as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

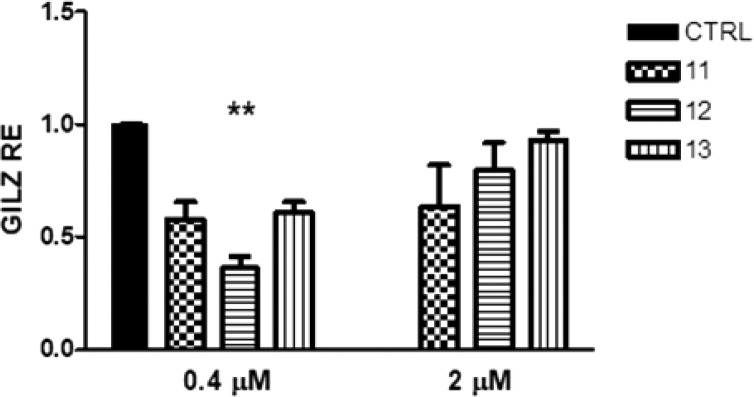

GILZ is one of the earliest and most GCR inducible genes by transactivation. To confirm the ability of compounds 11, 12, and 13 to modulate GCR transactivation, the expression of GILZ was measured in HeLa cells treated for 24 h with compounds 11, 12, and 13 at 0.4 and 2 μM. As shown in Figure 6, the compounds induced a downregulation of GILZ expression, by comparison to untreated cells (CTRL), indicating that our compounds could prevent the transactivation of the GCR. The strongest effect was observed for compound 12. GILZ downregulation was evident at lower concentration tested (0.4 μM), likely because at 2 μM the compounds start to induce a cytotoxic activity. To verify further the inhibition of GCR-induced transactivation, HeLa cells were also treated with DEX alone at 0.1 μM and in combination with compounds 11, 12, and 13 for 24 h (Figure 7). As a positive control, the GCR competitive antagonist RU486 was used in combination with DEX (Figure 7). Cotreatment of cells with DEX and RU486 showed that DEX-induced GCR-mediated GILZ transcription was inhibited as expected. Similar results were obtained when cells were treated with compounds 11, 12, and 13 plus DEX, with compound 12 showing again the most significant effect and likewise demonstrated the ability of this compound to inhibit the transcriptional activity of the GCR. The effect on GILZ expression of compounds 9 and 10 was also evaluated (Figure S10), highlighting that no significant inactivation of GCR is induced by these compounds since GILZ levels are not affected.

Figure 6.

GILZ expression in HeLa cells after treatment with 11, 12, and 13 for 24 h at 0.4 and 2 μM. One-way ANOVA; 0.4 μM, p = 0.0090; 2 μM, p = 0.58; Bonferroni post-test 12 vs CTRL, **p-value < 0.001. The data are reported as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 7.

GILZ expression in HeLa cells after treatment with DEX alone at 0.1 μM, with RU486 0.4 μM in combination with DEX and with 11, 12, and 13 at 0.4 μM in cotreatment with DEX for 24 h. One-way ANOVA, p = 0.011; Bonferroni post-test: RU486 + DEX vs DEX, *p-value < 0.05; 12 + DEX vs DEX, *p-value < 0.05. The data are reported as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

While in the GILZ expression assay, the compounds reduced DEX activity with an effect similar to RU486 (Figure 7), a competitive inhibitor of GCR; results from GCR reporter assay (Figure S8) indicate that the antagonism of our compounds is not surmountable by increasing DEX concentration and therefore occurs through a non-competitive mechanism.

In this letter, through an in vitro screening of 1200 compounds using a GCR reporter gene assay, nine molecules were identified as potent GCR antagonists. In addition, some analogs maintained an anti-inflammatory GCR-like activity as revealed by our NF-kB reporter gene studies. Molecular docking on the most active compound revealed the presence of three pockets suitable for binding. Based on the high density of HB donor residues found in these pockets, three novel compounds were designed. All the modified compounds displayed a lower binding energy in the selected pockets compared to the parent compound. The biological evaluation of the synthesized novel molecules did not show a classic antagonism against GCR but rather a reverse GCR transactivation, illustrated with a reduced expression of the GILZ gene. However, in contrast to RU486, our molecules failed to displace DEX in ligand binding assays. In silico studies provided three putative binding sites (pockets) in the ligand binding domain of the GCR where the compounds can bind in the presence of DEX.

Taking into account all the experimental data, we conclude that our novel analogues hold promise as a novel class of anti-inflammatory GCR modulator compounds with decreased GCR transactivation properties. Most importantly, given that they bind to the GCR but do not displace the reference ligand DEX,27,28 their allosteric binding is the most likely explanation.

These results open the door for designing improved anti-inflammatory GCR modulators with reduced side effects.

Acknowledgments

This research has been developed under the umbrella of CM1106 COST Action “Chemical Approaches for Targeting Drug Resistance in Cancer Stem Cells”. The authors express their gratitude to Ms. Ioana Stupariu for the revision of the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00527.

Preparation of compounds 11–13; in silico studies; description of in vitro evaluation GCR and NF-kB reporter gene studies; cell viability analysis; RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (TaqMan); Supplementary Figures, Tables, and Schemes (PDF)

Author Contributions

▲ These authors contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ratman D.; Vanden Berghe W.; Dejager L.; Libert C.; Tavernier J.; Beck I. M.; De Bosscher K. How glucocorticoid receptors modulate the activity of other transcription factors: a scope beyond tethering. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 380, 41–54. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K.; Vanden Berghe W.; Haegeman G. Cross-talk between nuclear receptors and nuclear factor kappaB. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6868–6886. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K.; Vanden Berghe W.; Haegeman G. The Interplay between the Glucocorticoid Receptor and Nuclear Factor-kB or Activator Protein-1: Molecular Mechanisms for Gene Repression. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 488–522. 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandevyver S.; Dejager L.; Libert C. Comprehensive overview of the structure and regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 671–693. 10.1210/er.2014-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. Anti-inflammatory glucocorticoids: changing concepts. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 724, 231–236. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K.; Beck I. M.; Ratman D.; Vanden Berghe W.; Libert C. Activation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor in Acute Inflammation: the SEDIGRAM Concept. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 4–16. 10.1016/j.tips.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirumamilla C. S.; Palagani A.; Kamaraj B.; Declerck K.; Verbeek M. W. C.; Oksana R.; De Bosscher K.; Bougarne N.; Ruttens B.; Gevaert K.; Houtman R.; De Vos W. H.; Joossens J.; Van Der Veken P.; Augustyns K.; Van Ostade X.; Bogaerts A.; De Winter H.; Vanden Berghe W. Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Properties of GSK866 Analogs with Cysteine Reactive Warheads. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1324. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. D. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 813–838. 10.2174/156802608784535011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman L. K.; Chrousos G. P.; Kellner C.; Spitz I. M.; Nisula B. C.; Cutler G. B.; Merriam G. R.; Bardin C. W.; Loriaux D. L. Successful Treatment of Cushing’s Syndrome with the Glucocorticoid Antagonist RU 486. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1985, 61, 536–540. 10.1210/jcem-61-3-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch G.; Gaillard-Moguilewsky M.; Lemoine G.; Nique F.; Philibert D. Design of ligands for the glucocorticoid and progestin receptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1991, 19, 901–908. 10.1042/bst0190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda M.; Kuroda T.; Kaneko S.; Aoki Y.; Yamashita M.; Okumura C.; Ikeda Y.; Ohbora T.; Sakaue M.; Koyama N.; Aritomo K. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Cyclopentaquinoline Derivatives as Nonsteroidal Glucocorticoid Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4918–4926. 10.1021/jm501758q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S.; Shiraishi F.; Kitamura S.; Kuroki H.; Jin K.; Kojima H. Characterization of steroid hormone receptor activities in 100 hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls, including congeners identified in humans. Toxicology 2011, 289, 112–121. 10.1016/j.tox.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z.; Lin H.; Srinivasan S.; Nwachukwu J. C.; Bruno N.; Griffin P. R.; Nettles K. W.; Kamenecka T. M. Synthesis of novel steroidal agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists for the glucocorticoid receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 347–353. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P.; Swick A. G.; Hargrove D. M.; LaFlamme J. A.; Moynihan M. S.; Carroll R. S.; Martin K. A.; Lee E.; Decosta D.; Bordner J. Discovery of Potent, Nonsteroidal, and Highly Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2417–2424. 10.1021/jm0105530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucafò M.; Stankovic B.; Kotur N.; Silvestre A. D.; Martelossi S.; Ventura A.; Zukic B.; Pavlovic S.; Decorti G. Pharmacotranscriptomic biomarkers in glucocorticoid treatment of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 10.2174/0929867324666170920145337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuriev E.; Agostino M.; Ramsland P. A. Challenges and advances in computational docking: 2009 in review. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011, 24, 149–164. 10.1002/jmr.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marucci C.; Christodoulou M. S.; Pieraccini S.; Sironi M.; Dapiaggi F.; Cartelli D.; Calogero A. M.; Cappelletti G.; Vilanova C.; Gazzola S.; Broggini G.; Passarella D. Synthesis of Pironetin–Dumetorine Hybrids as Tubulin Binders. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 11, 2029–2036. 10.1002/ejoc.201600130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Caporuscio F.; Restelli V.; Carlino L.; Cannazza G.; Costanzi E.; Citti C.; Lo Presti L.; Pisani P.; Battistutta R.; Broggini M.; Passarella D.; Rastelli G. Probing an allosteric pocket of CDK2 with small-molecules. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 33–41. 10.1002/cmdc.201600474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Mori M.; Pantano R.; Alfonsi R.; Infante P.; Botta M.; Damia G.; Ricci F.; Sotiropoulou P. A.; Liekens S.; Botta B.; Passarella D. Click Reaction as a Tool to Combine Pharmacophores: The Case of Vismodegib. ChemPlusChem 2015, 80, 938–943. 10.1002/cplu.201402435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laco G. S.; Collins J. R.; Luke B. T.; Kroth H.; Sayer J. M.; Jerina D. M.; Pommier Y. Human topoisomerase I inhibition: docking camptothecin and derivatives into a structure-based active site model. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 1428–1435. 10.1021/bi011774a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Zarate M.; Ricci F.; Damia G.; Pieraccini S.; Dapiaggi F.; Sironi M.; Lo Presti L.; García-Argáez A. N.; Dalla Via L.; Passarella D. 4-(1, 2-diarylbut-1-en-1-yl)isobutyranilide derivatives as inhibitors of topoisomerase II. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 118, 79–89. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navakauskienė R.; Mori M.; Christodoulou M. S.; Zentelytė A.; Botta B.; Dalla Via L.; Ricci F.; Damia G.; Passarella D.; Zilio C.; Martinet N. Histone demethylating agents as potential S-adenosyl-L-methionine-competitors. MedChemComm 2016, 7, 1245–1255. 10.1039/C6MD00170J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Zunino F.; Zuco V.; Borrelli S.; Comi D.; Fontana G.; Martinelli M.; Lorens J. B.; Evensen L.; Sironi M.; Pieraccini S.; Dalla Via L.; Gia O. M.; Passarella D. Camptothecin-7-yl-methanthiole: Semisynthesis and Biological Evaluation. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 2134–2143. 10.1002/cmdc.201200322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci C. G.; Netz P. A. Docking studies on DNA-ligand interactions: building and application of a protocol to identify the binding mode. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 1925–1935. 10.1021/ci9001537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Calogero F.; Baumann M.; García-Argáez A. N.; Pieraccini S.; Sironi M.; Dapiaggi F.; Bucci R.; Broggini G.; Gazzola S.; Liekens S.; Silvani A.; Lahtela-Kakkonen M.; Martinet N.; Nonell-Canals A.; Santamaría-Navarro E.; Baxendale J. R.; Dalla Via L.; Passarella D. Boehmeriasin A as new lead compound for the inhibition of topoisomerases and SIRT2. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 92, 766–775. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. S.; Sacchetti A.; Ronchetti V.; Caufin S.; Silvani A.; Lesma G.; Fontana G.; Minicone F.; Riva B.; Ventura M.; Lahtela-Kakkonen M.; Jarho E.; Zuco V.; Zunino F.; Martinet N.; Dapiaggi F.; Pieraccini S.; Sironi M.; Dalla Via L.; Gia O. M.; Passarella D. Quinazolinecarboline alkaloid evodiamine as scaffold for targeting topoisomerase I and sirtuins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 6920–6928. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec F.; Teubner V.; Tate D. Location of the Second Steroid-Binding Site on the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Endocrinology 1989, 125, 3103–3107. 10.1210/endo-125-6-3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svec F. Differences in the interaction of RU 486 and ketoconazole with the second binding site of the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 1988, 123, 1902–1906. 10.1210/endo-123-4-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.