Abstract

MAP-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) plays an important role in the regulation of innate immune response as well as in cell survival upon DNA damage. Despite its potential for the treatment of inflammation and cancer, to date no MK2 low molecular weight inhibitors have reached the clinic, mainly due to inadequate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties. We describe here an approach based on specifically placed fluorine within a recently described pyrrole-based MK2 inhibitor scaffold for manipulation of its physicochemical and ADME properties. While preserving target potency, the novel fluoro-derivatives showed greatly improved permeability as well as enhanced solubility and reduced in vivo clearance leading to significantly increased oral exposure.

Keywords: MK2, fluorine, permeability, ADME properties, pharmacokinetic, directed ortho metalation

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine and the major driver of systemic inflammation.1,2 Its overexpression is linked to several autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases. At present, patients can profit from anti-TNFα therapy using marketed biologics, like adalimumab (Humira), etanercept (Enbrel), or infliximab (Remicade).3 Nonetheless, a small molecular weight orally bioavailable drug blocking TNFα production would be highly desirable. MK2, or MAPKAPK2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase activated protein kinase 2), is a serine/threonine kinase and a downstream substrate of p38.4−8 Due to its important role in TNFα secretion and inflammation, p38 was extensively explored as a therapeutic target for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.9 Despite several p38 inhibitors entering clinical trials,10 none of them reached phase 3, mainly due to their poor safety profile and observed hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity (p38 is involved in the regulation of more than 60 substrates), but also their lack of long-term efficacy due to counter activation of transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) as a result of p38 inhibition (TAK1 feedback loop).11 Hence, MK2 was proposed as an alternative target for inhibition of the pathway while avoiding p38-dependent side effects.7 Beyond its role in the regulation of inflammation, MK2 was recently shown to be involved in the G2/M checkpoint arrest upon DNA damage, thus contributing to the resistance of p53-deficient tumors to cisplatin.12 In addition, MK2 also displayed a synergistic effect with checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) inhibition leading to a mitotic catastrophe in KRAS mutant cells.13 Most of the low molecular weight MK2 inhibitors reported to date are restricted by their physicochemical properties leading to mediocre cellular potency and/or efficacy in animal models,7,8 ultimately preventing them from advancing into clinical trials.

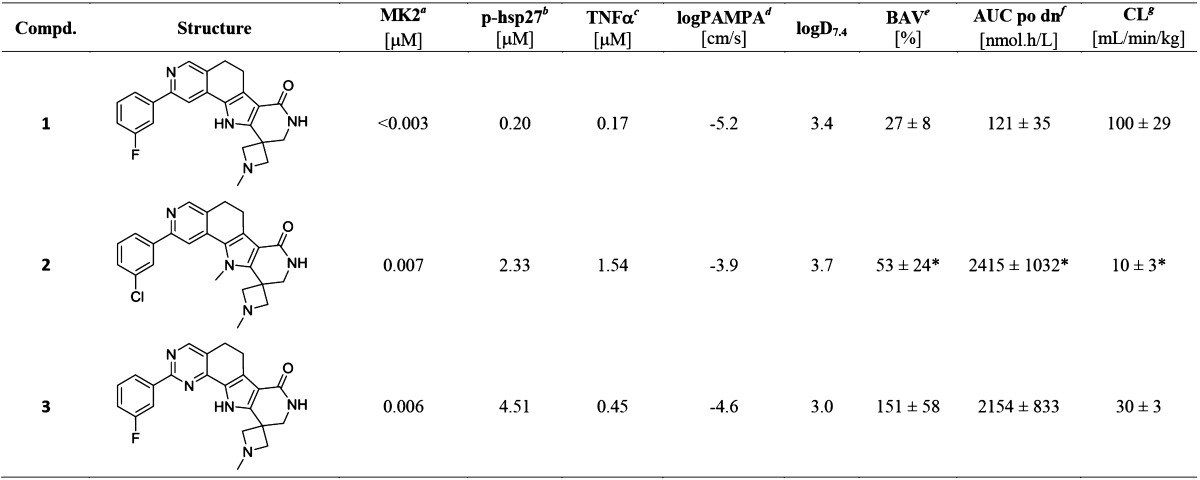

Oral bioavailability, the fraction of the oral dose reaching systemic circulation, is predominantly dependent on intestinal absorption of a drug and its first-pass metabolism.14,15 Oral absorption relies on the drug’s permeability and aqueous solubility and is influenced by four key-parameters: molecular weight, logP, number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA), and form the basis of Lipinski’s “rule of five” for prediction of absorption.16 As a part of our interest in MK2 inhibitors,17−21 we have recently described a series of pentacyclic type 1 (ATP-competitive) MK2 inhibitors20,21 represented by compound 1 (Table 1). During lead optimization, combining good cellular potency with acceptable oral exposure in rodents was challenging in this series. Usually, potent MK2 inhibitors like 1 suffered from insufficient oral bioavailability and permeability while not violating the rule of five. The primary cause of the unfavorable oral exposure appeared to be the presence of a pyrrole-NH. As illustrated by compound 2 (Table 1), methylation of the pyrrole-NH greatly improved permeability, as assessed by parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA). Notably, the superior penetration of derivative 2 did not result from a presumably increased lipophilicity as the logD7.4 measured for compounds 1 and 2 was virtually the same (Table 1). This indicates that HBD strength of the pyrrole-NH rather than lipophilicity22 might be responsible for the poor permeability of such compounds, a hypothesis further supported by analog 3. Counterintuitively, an additional HBA in 3 led to improved permeability suggesting the pyrimidine nitrogen to influence the pyrrole-NH HBD strength. The overproportional increase in rat oral exposure observed for compounds 2 and 3 could be explained by further improvement in their rat in vivo clearance compared to 1 (Table 1).

Table 1. MK2 Inhibitors: Challenge to Combine Cellular Potency with Good Oral Exposure.

IC50 values determined as a mean (n ≥ 2) of ahuman MK2 kinase activity, binhibition of hsp27 phosphorylation in anisomycin stimulated THP-1 cells, and cLPS stimulated TNFα release from human PBMCs. dPermeability determined by high-throughput PAMPA. eOral bioavailability ± SD calculated as dose normalized ratio of extravascular AUCextrap to iv AUCextrap; both parameters determined as a mean of 4 animals (female Sprague–Dawley rat). fExposure (AUC; dn = dose-normalized to 1 mg/kg) ± SD measured as a mean of 4 animals (female Sprague–Dawley rat) after po dosing (3 mg/kg) using CMC/water/Tween (0.5:99:0.5) formulation. gClearance measured as a mean ± SD of 4 animals (Sprague–Dawley rat) after iv dosing (1 mg/kg) using NMP/PEG200 (30:70) formulation. *Values determined over 8 h (= t-last).

Unfortunately, the described modifications of derivatives 2 and 3 reduced their potency on MK2 biochemical activity and in cellular systems (inhibition of heat shock protein 27 (hsp27) phosphorylation in anisomycin stimulated human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) or by inhibition of TNFα release in LPS stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)). Whereas this was not surprising for analog 2, since the pyrrole-NH was shown to be involved in a water mediated interaction with the enzyme,19,20 the decreased MK2 potency for pyrimidine derivative 3 was less predictable. This might, however, be an indication again for the reduction in pyrrole-HBD strength caused by the additional nitrogen in 3.

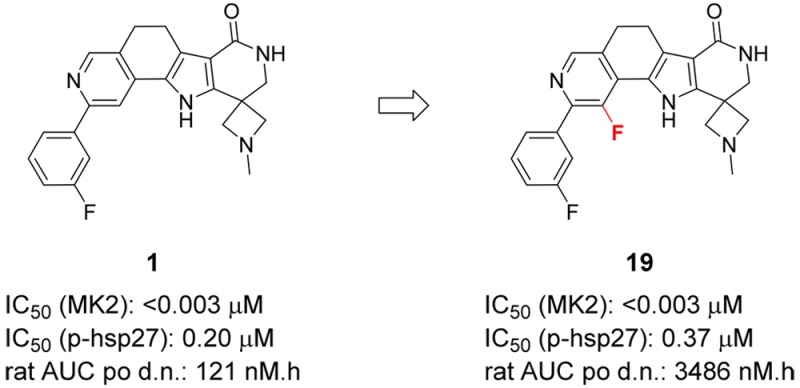

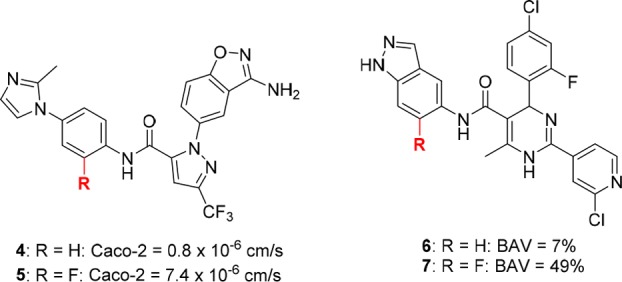

A suitably positioned fluorine23 has been shown to improve permeability and oral bioavailability of amides with otherwise poor oral absorption while retaining the target potency as exemplified by paired derivatives 4/524 and 6/725 (Figure 1). Since a C–F group can serve as a bioisostere of nitrogen in azines and azoles,26−28 we wished to explore the effect of fluorine in the 3-position of pyridine (like in 19, Figure 2) for its ability to modulate permeability and oral absorption while hoping to keep the MK2 potency.

Figure 1.

Examples of a positive influence of fluorine on permeability and bioavailability.

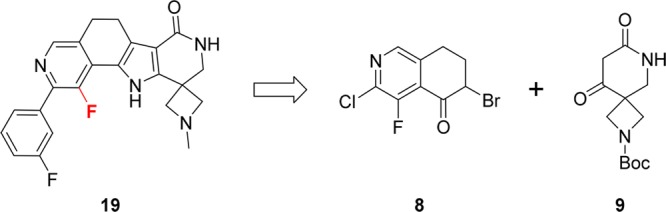

Figure 2.

Proposed fluoro-containing analog 19 and its synthesis plan.

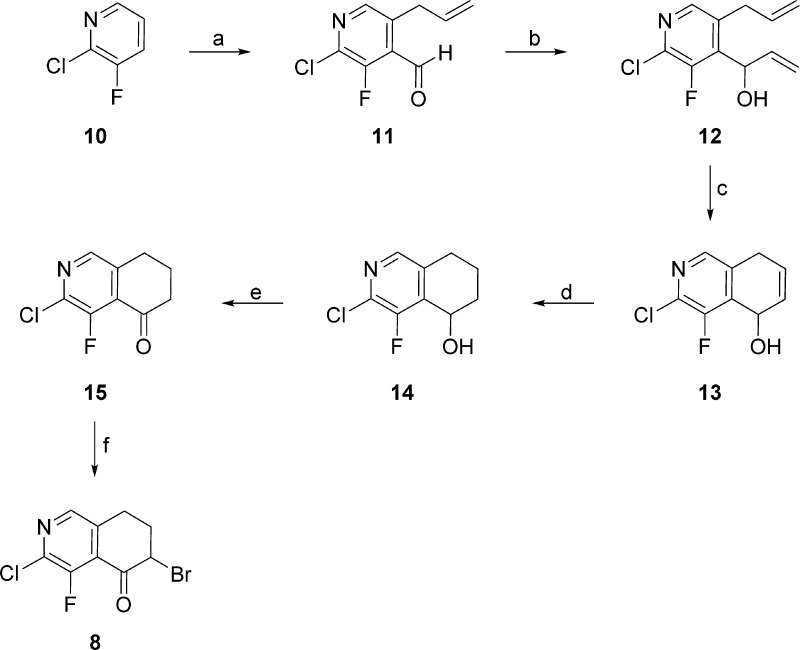

In analogy to the previously described synthesis of compound 1,20,21the synthesis of the proposed F-pentacycle 19 was envisioned to be achieved by the Hantzsch pyrrole synthesis using bromoketone 8 and spiropiperidinedione 9 (Figure 2). While compound 9 was prepared according to the described procedure,21 bromoketone 8 could be obtained from compound 15 (Scheme 1). Synthesis of 15 has been recently developed and published by our group29 and starts with the preparation of tetrasubstituted pyridine 11 from commercially available 3-fluoro-2-chloropyridine (10) using Comins’ protocol30 for sequential directed ortho-metalations (DOM). The first DOM of 10 was achieved with t-BuLi, and the formed 4-pyridyl anion readily underwent the Bouveault reaction with N-formyl-N,N′,N′-trimethylethylene-1,2-diamine providing an α-amino alkoxide. This protected aldehyde intermediate allowed for a second DOM with n-BuLi leading to a 5-pyridyl lithium species that had to be transmetalated into a cuprate in order to enable its alkylation by allyl bromide. The five-step one-pot reaction provided the desired product 11 in a satisfactory yield. The required bromoketone 8 was obtained from 11 by addition of vinyl Grignard to the aldehyde, followed by ring-closing metathesis of diene 12, reduction of alkene double bond in 13, oxidation of alcohol 14, and α-bromination of the formed ketone 15 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Fluoropyridine Building Block 8 Using Comins’ Method for Double Directed ortho-Metalation as a Key Step.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) t-BuLi, THF, −78 °C, 1 h, (2) Me2NCH2CH2NMeCHO, −78 to −40 °C, (3) n-BuLi, −40 to −30 °C, 3 h, (4) CuBr, −30 to 0 °C, 1 h, (5) allyl bromide, −30 to −10 °C, 1 h (41%); (b) vinyl bromide, THF, 0 °C, 1 h (76%); (c) Grubbs II (cat.), CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h (97%); (d) H2 (1 atm), PtO2 (cat.), MeOH, rt, 1 h (73%); (e) (ClCO)2, DMSO, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −60 °C to rt, 4 h (89%); (f) Br2, HBr, AcOH, rt to 35 °C, 15 min (98%).

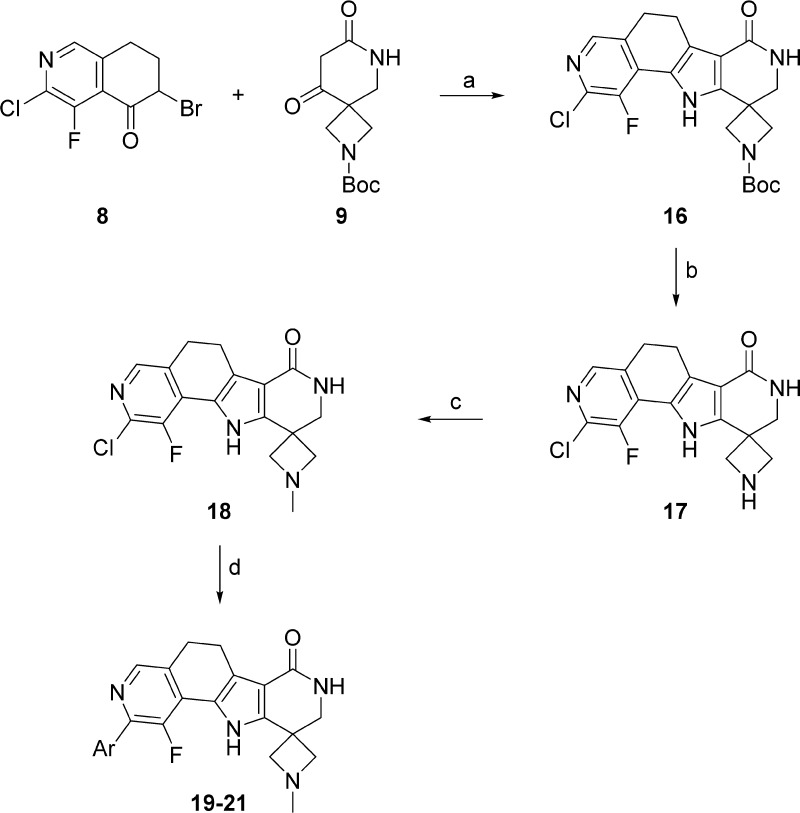

Condensation of the bromoketone 8 with the spiro-piperidinedione 9 in the presence of ammonium acetate provided the expected pyrrole intermediate 16 (Scheme 2). After removal of the Boc-protecting group, the free azetidine-NH in 17 was methylated by formaldehyde under reductive amination conditions. The final compounds 19–21 were obtained from the chloropyridine intermediate 18 by Suzuki coupling.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Fluoro-Containing Analogs 19–21.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NH4OAc, MeOH, 60 °C, 3 h (85%); (b) HCl, dioxane, rt, 3 h (100%); (c) formaldehyde, NaBH(OAc)3, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h (39%); (d) Ar–B(OH)2, Na2CO3, PdCl2(PPh3)2, PPh3, n-PrOH/H2O, 150 °C, 15 min (53–66%).

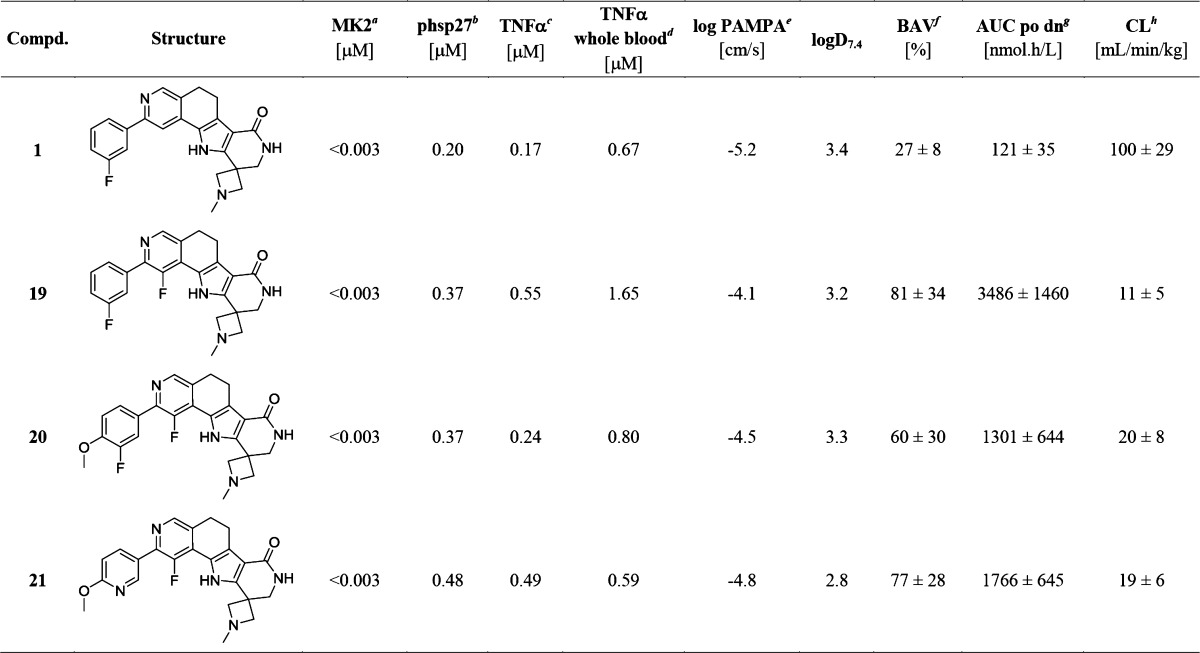

Gratifyingly, the newly obtained 3-fluoropyridine containing compounds 19–21 showed robust MK2 inhibition (Table 2) and maintained potency at the level of non-fluoro analog 1 as assessed by biochemical and cellular assays (p-hsp27 and TNFα). Furthermore, these new derivatives potently inhibited TNFα release from human blood, with compound 21 being identified as the best candidate. In line with our hypothesis, the permeability of the fluoro-containing derivatives could indeed be significantly improved (by 1 log unit in PAMPA comparing analog 19 to 1). Similarly to N-methylated pyrrole analog 2, the improved permeability of fluoro-analog 19 was not driven by an increased lipophilicity as its logD7.4 remained comparable to that of compound 1 (Table 2).

Table 2. Fluoro-Containing Pentacyclic MK2 Inhibitors Showed Improved Physicochemical and Pharmacokinetic Parameters Whilst Preserving Target Potency.

IC50 values determined as a mean (n ≥ 2) of ahuman MK2 inhibition, binhibition of hsp27 phosphorylation in anisomycin stimulated THP-1 cells, cTNFα release inhibition in LPS stimulated human PBMCs, and dinhibition of LPS stimulated TNFα release from human whole blood. ePermeability determined by high-throughput PAMPA. fOral bioavailability ± SD calculated as dose normalized ratio of extravascular AUCextrap to iv AUCextrap, both parameter determined as a mean ± SD of 4 animals (female Sprague–Dawley rat). gOral exposure measured as a mean ± SD of 4 animals (female Sprague–Dawley rat) after po dosing (3 mg/kg) using CMC/water/Tween (0.5:99:0.5) formulation, dn = dose-normalized to 1 mg/kg. hClearance measured as a mean ± SD of 4 animals (Sprague–Dawley rat) after iv dosing (1 mg/kg) using NMP/PEG200 (30:70) formulation.

In addition to the superior permeability, fluorination of the pentacyclic core led also to improved solubility31 (0.032 g/L for 19 vs 0.004 g/L for 1) as well as rat in vivo clearance (11 mL/min/kg for 19 vs 100 mL/min/kg for 1). It is quite remarkable what effect a single atom can have32 on multiple ADME parameters, especially considering that permeability typically diverges from solubility and clearance during optimization. The improved physicochemical properties consequently led to better oral absorption of such compounds as revealed by an increase in rat oral bioavailability (Table 2). The enhanced oral absorption together with decreased clearance observed for the fluoro-containing analogs resulted in a significantly improved oral exposure (3486 nM·h for 19 vs 121 nM·h for 1). Taken together with the attractive MK2 potency achieved with the fluoro analogs 19–21, this study demonstrates that a fluorine atom can be a highly useful tool for tuning ADME properties while not interfering with target potency. This new modification may also enable further optimization of the scaffold toward MK2 inhibitors with improved in vivo efficacy.

In conclusion, a new fluoro-containing MK2 inhibitor scaffold has been described. After observation that the pyrrole-NH within the previously described pyrrole-based MK2 inhibitors was responsible for their poor physicochemical and ADME properties, an influence of a fluorine atom placed into its proximity was studied for the modulation of such parameters. The designed fluoro-containing analogs were synthesized using a Hantzsch pyrrole synthesis. The required fluoro-containing building block 8 could be assembled utilizing a remarkable one-pot, five-step sequence employing Comins’ protocol for two subsequent directed ortho-metalations. The obtained fluoro-analogs 19–21 displayed improved permeability, while, surprisingly, also other ADME parameters such as solubility and in vivo clearance could be improved leading to a significantly enhanced oral exposure. At the same time, target potency was retained, thus demonstrating that fluorine, when properly placed within a scaffold, can be a highly useful tool for improvement of physicochemical and ADME properties while not affecting target binding. In addition, we believe that these new analogs can be valuable for further exploration of MK2 biology in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Guido Koch, Henrik Möbitz, Suzanne Skolnik, and Thomas Lochmann for valuable discussions; Stephane Rodde and Damien Hubert for the physicochemical measurements; Elodie Letot for IR measurements; and Corinne Marx and Jürgen Kühnöl for HRMS measurements.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BAV

bioavailability

- CMC

carboxymethylcellulose

- DIPEA

ethyldiisopropyl amine.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00098.

Description of in vitro assays, pharmacokinetic measurements, synthesis procedures and characterization data for all compounds, and UPLC and NMR charts (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Parameswaran N.; Patial S. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expression 2011, 20, 87–103. 10.1615/CritRevEukarGeneExpr.v20.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. D.; Nedjai B.; Hurst T.; Pennington D. J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali T.; Kaitha S.; Mahmood S.; Ftaisi A.; Stone J.; Bronze M. S. Clinical use of anti-TNF therapy and increased risk of infections. Drug, Healthcare Patient Saf. 2013, 5, 79–99. 10.2147/DHPS.S28801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaestel M. What goes up must come down: molecular basis of MAPKAP kinase 2/3-dependent regulation of the inflammatory response and its inhibition. Biol. Chem. 2013, 394, 1301–1315. 10.1515/hsz-2013-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K. R.; Najmi K. A.; Dastidar G. S. Pharmacological reports biological functions and role of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activated Protein Kinase 2 (MK2) in inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 746–756. 10.1016/j.pharep.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgis F. M. S.; Ziaziaris W.; Munoz L. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Activated Protein Kinase 2 in neuroinflammation, Heat shock protein 27 phosphorylation, and cell cycle: role and targeting. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 85, 345–356. 10.1124/mol.113.090365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M.; Forli S.; Manetti F. Targeting Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Activated Protein Kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2, MK2): Medicinal chemistry efforts to lead small molecule inhibitors to clinical trials. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 3609–3634. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapbach A.; Huppertz C. Low-molecular-weight MK2 inhibitors: a tough nut to crack!. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 1243–1257. 10.4155/fmc.09.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwal R. P.; Bhadauriya A.; Damre M. V.; Dhoke G. V.; Sangamwar A. T. p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase inhibitors: a review on pharmacophore mapping and QSAR studies. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1015–1035. 10.2174/1568026611313090005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L.; Chemistry B. Clinical candidates of small molecule p38 MAPK inhibitors for inflammatory diseases. MAP Kinase 2015, 4, 24–30. 10.4081/mk.2015.5508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P. C. F.; Campbell D. G.; Nebreda A. R.; Cohen P. Feedback control of the protein kinase TAK1 by SAPK2α/p38α. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5793–5805. 10.1093/emboj/cdg552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandell S.; Reinhardt H. C.; Cannell I. G.; Kim J. S.; Ruf D. M.; Mitra T.; Couvillon A. D.; Jacks T.; Yaffe M. B. A reversible gene-targeting strategy identifies synthetic lethal interactions between MK2 and p53 in the DNA damage response in vivo. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 868–877. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietlein F.; Kalb B.; Jokic M.; Noll E. M.; Strong A.; Tharun L.; Ozretić L.; Künstlinger H.; Kambartel K.; Randerath W. J.; Jüngst C.; Schmitt A.; Torgovnick A.; Richters A.; Rauh D.; Siedek F.; Persigehl T.; Mauch C.; Bartkova J.; Bradley A.; Sprick M. R.; Trumpp A.; Rad R.; Saur D.; Bartek J.; Wolf J.; Büttner R.; Thomas R. K.; Reinhardt H. C. A Synergistic interaction between Chk1- and MK2 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant cancer. Cell 2015, 162, 146–159. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungst B. J. Optimizing oral bioavailability in drug discovery: an overview of design and testing strategies and formulation options. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 921–929. 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. A., van de Waterbeemd H., Walker D. K., Eds. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism in Drug Design; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A.; Lombardo F.; Dominy B. W.; Feeney P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapbach A.; Feifel R.; Hawtin S.; Heng R.; Koch G.; Moebitz H.; Revesz L.; Scheufler C.; Velcicky J.; Waelchli R.; Huppertz C. Pyrrolo-pyrimidones: A novel class of MK2 inhibitors with potent cellular activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 6142–6146. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcicky J.; Feifel R.; Hawtin S.; Heng R.; Huppertz C.; Koch G.; Kroemer M.; Moebitz H.; Revesz L.; Scheufler C.; Schlapbach A. Novel 3-aminopyrazole inhibitors of MK-2 discovered by scaffold hopping strategy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1293–1297. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revesz L.; Schlapbach A.; Aichholz R.; Feifel R.; Hawtin S.; Heng R.; Hiestand P.; Jahnke W.; Koch G.; Kroemer M.; Möbitz H.; Scheufler C.; Velcicky J.; Huppertz C. In vivo and in vitro SAR of tetracyclic MAPKAP-K2 (MK2) inhibitors. Part I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4715–4718. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revesz L.; Schlapbach A.; Aichholz R.; Dawson J.; Feifel R.; Hawtin S.; Littlewood-Evans A.; Koch G.; Kroemer M.; Möbitz H.; Scheufler C.; Velcicky J.; Huppertz C. In vivo and in vitro SAR of tetracyclic MAPKAP-K2 (MK2) inhibitors. Part II. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4719–4723. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapbach A.; Revesz L.; Koch G. Heterocyclic compounds useful as MK2 inhibitors and their preparation, pharmaceutical compositions and use in the treatment of diseases. WO 2009010488. Chem. Abstr. 2009, 150, 168327. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. S.; Berry D. J.; Brown H. S.; Buckett L.; Clarke D. S.; Goldberg K.; Hudson J. A.; Leach A. G.; MacFaul P. A.; Raubo P.; Robb G. Achieving improved permeability by hydrogen bond donor modulation in a series of MGAT2 inhibitors. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 1305–1311. 10.1039/c3md00156c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2529–2591. 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan M. L.; Lam P. Y. S.; Han Q.; Pinto D. J. P.; He M. Y.; Li R.; Ellis C. D.; Clark C. G.; Teleha C. A.; Sun J.-H.; Alexander R. S.; Bai S.; Luettgen J. M.; Knabb R. M.; Wong P. C.; Wexler R. R. Discovery of 1-(30-aminobenzisoxazol-50-yl)-3-trifluoromethyl-N-[2-fluoro-4-[(20-dimethylaminomethyl)imidazol-1-yl]phenyl]-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxyamide hydrochloride (razaxaban), a highly potent, selective, and orally bioavailable factor Xa inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1729–1744. 10.1021/jm0497949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehon C. A.; Wang G. Z.; Viet A. Q.; Goodman K. B.; Dowdell S. E.; Elkins P. A.; Semus S. F.; Evans C.; Jolivette L. J.; Kirkpatrick R. B.; Dul E.; Khandekar S. S.; Yi T.; Wright L. L.; Smith G. K.; Behm D. J.; Bentley R.; Doe C. P.; Hu E.; Lee D. Potent, selective and orally bioavailable dihydropyrimidine inhibitors of rho kinase (ROCK1) as potential therapeutic agents for cardiovascular diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6631–6634. 10.1021/jm8005096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries A. C.; Gancia E.; Gilligan M. T.; Goodacre S.; Hallett D.; Merchant K. J.; Thomas S. R. 8-Fluoroimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine: synthesis, physicochemical properties and evaluation as a bioisosteric replacement for imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine in an allosteric modulator ligand of the GABAA receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1518–1522. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. T.; Blackaby W. P.; Blackburn T.; Jennings A. S. R.; Pike A.; Wilson R. A.; Hallett D. J.; Cook S. M.; Ferris P.; Marshall G. R.; Reynolds D. S.; Sheppard W. F. A.; Smith A. J.; Sohal B.; Stanley J.; Tye S. J.; Wafford K. A.; Atack J. R. A Pyridazine series of α2/α3 subtype selective GABAA agonists for the treatment of anxiety. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2600–2610. 10.1021/jm051144x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcicky J.; Pflieger D. Synthesis of 3-chloro-4-fluoro-7,8-dihydro-6H-isoquinolin-5-one and its derivatives. Synlett 2010, 2010, 1397–1401. 10.1055/s-0029-1219818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comins D. L.; Baevsky M. F.; Hong H. A 10-step, asymmetric synthesis of (S)-Camptothecin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10971. 10.1021/ja00053a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan A. P.; Chaturvedula P. V.; Conway C. M.; Cook D. A.; Davis C. D.; Denton R.; Han X.; Macci R.; Mathias N. R.; Moench P.; Pin S. S.; Ren S. X.; Schartman R.; Signor L. J.; Thalody G.; Widmann K. A.; Xu C.; Macor J. E.; Dubowchik G. M. Discovery of (R)-4-(8-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)-N-(3-(7-methyl-1H-indazol-5-yl)-1-oxo-1-(4-(piperidin-1-yl)piperidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)-piperidine-1-carboxamide (BMS-694153): a potent antagonist of the human calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor for migraine with rapid and efficient intranasal exposure. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4858–4861. 10.1021/jm800546t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger D. L. The difference a single atom can make: synthesis and design at the chemistry-biology interface. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11961–11980. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.