Abstract

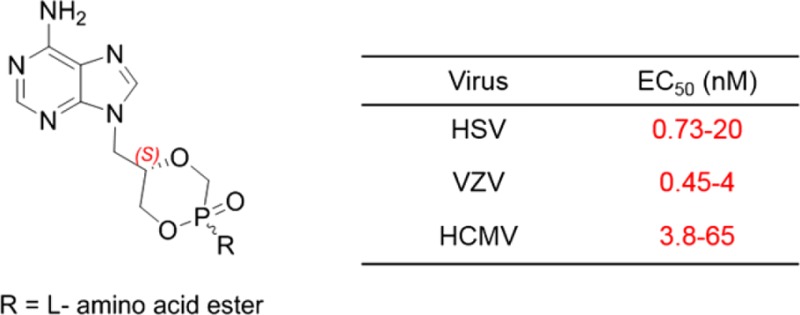

A series of amidate prodrugs of cyclic 9-[3-hydroxy-2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine (cHPMPA) featuring different amino acid motifs were synthesized. All phosphonamidates derived from (S)-cHPMPA displayed a broad spectrum activity against herpesviruses with EC50 values in the low nanomolar range. A phosphonobisamidate prodrug of (S)-HPMPA also exhibited a remarkably potent antiviral activity. In addition, the leucine ester prodrug of (S)-cHPMPA and phosphonobisamidate valine ester prodrug of (S)-HPMPA proved stable in human plasma. These data warrant further development of cHPMPA prodrugs, especially against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), for which there is a high need for treatment in transplant recipients.

Keywords: acyclic nucleoside phosphonates, phosphonamidate prodrugs, DNA viruses, antiviral activity, metabolic stability

Human herpesviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the Herpesviridae family, which includes nine human viruses causing a wide range of diseases. In particular, the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily comprises herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV), while human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and human herpes viruses 6A, 6B, and 7 (HHV-6A, HHV-6B, and HHV-7) are classified as Betaherpesvirinae. Epstein–Barr virus and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, considered as oncogenic viruses, belong to the Gammaherpesvirinae.1,2

All drugs currently marketed for the treatment of herpesvirus infections, such as acyclovir, ganciclovir, penciclovir, and brivudine, target viral DNA polymerases.3−5 For several of these compounds, some prodrugs also received marketing approval (valacyclovir, valganciclovir, and famciclovir). The antiviral activity of these “classical” nucleosides depends upon their intracellular metabolism within virus-infected cells to be sequentially converted to the mono-, di-, and triphosphates. The latest are the pharmacologically active species, as they can be incorporated into a growing viral DNA strand by viral DNA polymerases, resulting in chain termination or fraudulent DNA. Cidofovir [(S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine, (S)-HPMPC)] is an acyclic nucleoside phosphonate analogue (Figure 1), which is essentially a monophosphate mimic, officially approved as injectable medication for the treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in AIDS patients.6 Its adenine counterpart, namely (S)-HPMPA (Figure 1), was also described to exhibit a similarly potent inhibitory activity against a broad spectrum of DNA viruses7 while showing greater toxicity in vitro.8,9 Owing to the presence of the phosphonate moiety, such nucleotide analogues are metabolically stable and do not depend on viral enzymes for activation but undergo only two phosphorylation steps by cellular kinases.

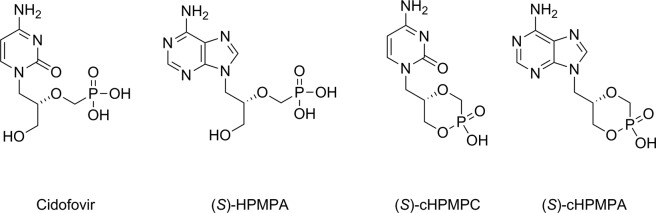

Figure 1.

Structures of (S)-HPMP and (S)-cHPMP nucleoside analogues active against DNA viruses.

To reduce the recognized toxic side effects associated with the use of HPMP-type nucleosides, their corresponding cyclic forms (S)-cHPMPC and (S)-cHPMPA (Figure 1) were synthesized and shown to retain the remarkable antiviral potency of the parent compounds while allowing for improved selectivity indexes.10,11

However, all of these HPMP derivatives invariably suffer from a low oral bioavailability due to the presence of negatively charged group(s) at physiological pH that restrict their ability to penetrate the lipid-rich cell membrane. Therefore, the development of orally bioavailable, less toxic prodrug forms of cHPMPs is highly desirable. Up to now, no prodrugs of (S)-HPMPA have been approved for clinical use, while the derivatization of cHPMPA has purely focused on the synthesis of phosphoester prodrugs.12,13

One of the most promising prodrug strategies that has been developed over the past few years for nucleoside phosphates and phosphonates is the use of aryloxy monoamidates.14 This approach has not been applied to HPMP-based compounds, owing to the potential chemical instability of the resulting phenoxyphosphonoamidate with concomitant formation of a cyclic phosphonate analogue. Thus, we decided to exploit this reactivity in order to synthesize a series of phosphono amidate prodrugs of cHPMPA bearing different amino acid motifs.

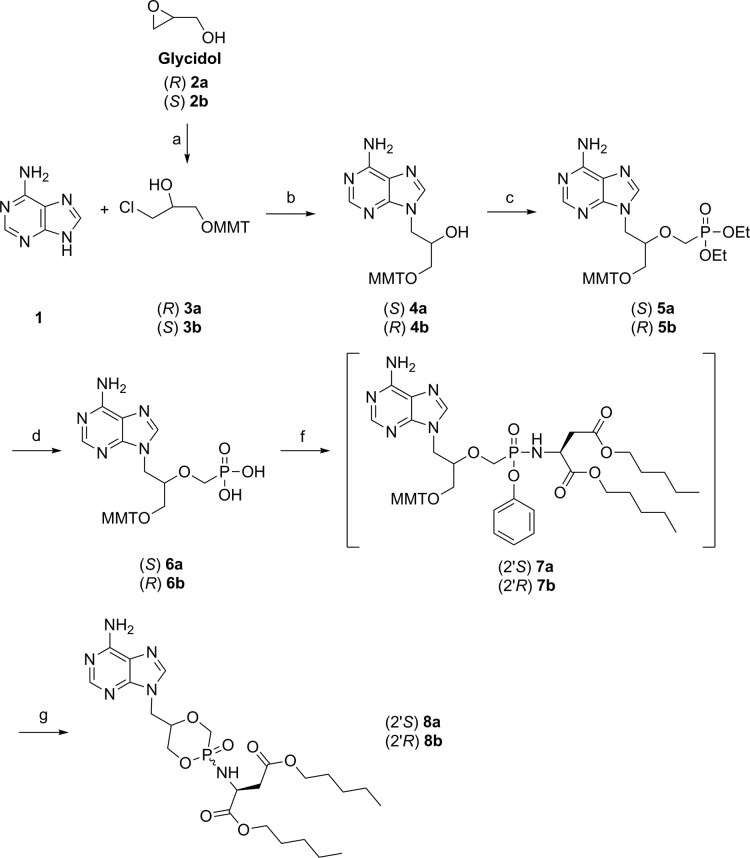

Given the well-established beneficial effect of a l-aspartic acid amyl ester moiety instead of the classical l-alanine ester on the antiviral activity of different phosphonamidate prodrugs,15−17 our study started with the synthesis of the l-aspartate prodrugs of (R)- and (S)-cHPMPA. Both enantiomers of MMT-protected HPMPA 6a/b could be readily obtained from commercially available (R)-(+)- and (S)-(−)-glycidol 2a/b, as illustrated in Scheme 1. Interestingly, when 2a/b were subjected to a tritylation reaction in the presence of pyridine as base, ring-opened compounds 3a/b were formed as the sole products instead of the anticipated MMT-glycidols.18 The following alkylation of 3-chloro-1-O-monomethoxytrityl-1,2-propanediols 3a/b with adenine in the presence of 0.9 equiv of sodium hydride afforded moderate yields (40–50%) of compounds 4a/b in a regioselective and stereospecific manner. Subsequently, the phosphonate group was introduced using diethyl tosyloxymethylphosphonate and NaH, furnishing 5a/b in 35–40% yield. Standard hydrolysis of the diester group with TMSBr in dry acetonitrile was carried out overnight to form 6a/b in good yield. The free phosphonic acid moiety of 6a/b was then converted into the corresponding key intermediate aryloxyphosphonamidates 7a/b by treatment with l-aspartic acid diamyl ester (Asp-diamyl)17 and phenol using 2,2′-dithiodipyridine and triphenylphosphine as activating agents.19 Under acid conditions, the phenoxy group served as a good leaving group, efficiently generating cyclic (S)/(R)-phosphonamidates 8a/b.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of (S)- and (R)-cHPMPA l-Asp-diamylphosphonamidates 8a and 8b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) MMTCl, Pyr, 50 °C, 20 h, 80%; (b) NaH, DMF, 110 °C, 6 h, 40–50%; (c) diethyl tosyloxymethylphosphonate, NaH, THF, 0 °C to rt, 5 h, 35–40%; (d) TMSBr, 2,6-lutidine, CH3CN, 0 °C to rt, 12 h, 70%; (f) (i) l-aspartic acid amyl ester HCl salt, PhOH, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, PPh3, Et3N, Pyr, 60 °C, 12 h; (g) TCA (6% in DCM), rt, 2 h, 37–42% over 2 steps.

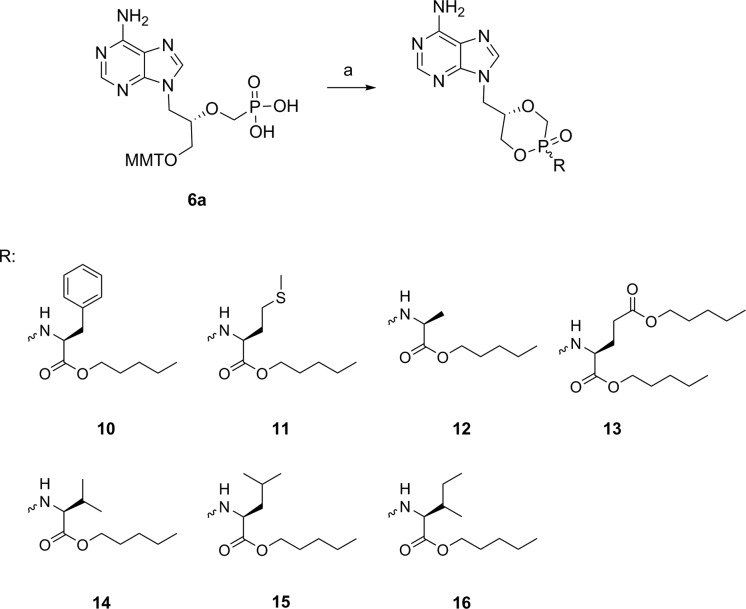

Additionally, guided by the preliminary data obtained for 8a/b (Table 1) and in order to determine the influence of the amino acid side chain on the antiviral activity, a restricted library of (S)-cHPMPA phosphonoamidate prodrugs 10–16 was prepared by introducing a range of structural variations. To this aim, phosphonoacid 6a was coupled with a variety of l-amino acid (phenylalanine, methionine, alanine, glutamic acid, valine, leucine, and isoleucine) esters yielding the desired compounds in moderate yields over two steps (Scheme 2).

Table 1. Antiviral Activity and Cytotoxicity of Compounds 8a and 8b and 10–17 against HSV, VZV, and HCMV in HEL Cells.

| antiviral

activity EC50a (μM) |

cytotoxicity

(μM) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | HSV-2 | VZV |

HCMV |

MCCb | CC50c | |||||

| Cmpd | KOS strain | KOS ACVr strain | G strain | TK+ strain (OKA) | TK– strain (07–1) | AD-169 starin | Davis strain | HEL | HEL | clogPd |

| 8a | 0.0032 ± 0.0043 | 0.0073 ± 0.00043 | 0.0020 ± 0.0015 | 0.0014 ± 0.0011 | 0.0015 ± 0.00080 | 0.027 ± 0.027 | 0.0090 ± 0.0051 | 13.6 ± 8.54 | 2.73 ± 0.50 | 2.22 |

| 8b | 0.21 ± 0.14 | 0.076 ± 0.063 | 0.11 ± 0.068 | 0.033 ± 0.020 | 0.062 ± 0.042 | 4.39 ± 3.61 | 1.62 ± 1.21 | >18.5 | 11.6 ± 3.86 | 2.22 |

| 10 | 0.0035 ± 0.0027 | 0.0015 ± 0.00037 | 0.0023 ± 0.00044 | 0.00052 ± 0.00074 | 0.0032 ± 0.0026 | 0.031 ± 0.023 | 0.017 ± 0.0061 | 9.29 ± 9.19 | 30.6 ± 24.4 | 3.34 |

| 11 | 0.0089 ± 0.0075 | 0.0057 ± 0.0049 | 0.011 ± 0.0050 | 0.0026 ± 0.0024 | 0.0040 ± 0.0021 | 0.032 ± 0.014 | 0.029 ± 0.011 | 4.11 ± 8.54 | 39.6 ± 25.8 | 2.07 |

| 12 | 0.020 ± 0.015 | 0.010 ± 0.010 | 0.017 ± 0.011 | 0.0020 ± 0.0015 | 0.0043 ± 0.00067 | 0.064 ± 0.015 | 0.065 ± 0.017 | 23.5 | 3.40 ± 0.40 | 1.93 |

| 13 | 0.0012 ± 0.00015 | 0.0012 ± 0.00084 | 0.0025 ± 0.0029 | 0.00058 ± 0.00067 | 0.00095 ± 0.00029 | 0.014 ± 0.012 | 0.0076 ± 0.0072 | 13.2 ± 8.33 | 0.52 ± 0.051 | 3.53 |

| 14 | 0.0030 ± 0.0023 | 0.0018 ± 0.0015 | 0.0042 ± 0.0025 | 0.00057 ± 0.00035 | 0.0015 ± 0.00029 | 0.0059 ± 0.0014 | 0.0048 ± 0.00033 | 4.4 | 7.76 ± 4.03 | 2.85 |

| 15 | 0.0013 ± 0.00079 | 0.0013 ± 0.00072 | 0.0019 ± 0.0010 | 0.00047 ± 0.0035 | 0.00059 ± 0.0011 | 0.0057 ± 0.0030 | 0.0038 ± 0.00025 | 4.27 | 1.62 ± 0.91 | 2.38 |

| 16 | 0.0020 ± 0.0012 | 0.0019 ± 0.0019 | 0.0027 ± 0.0012 | 0.00045 ± 0.00045 | 0.00054 ± 0.00026 | 0.0070 ± 0.0028 | 0.0065 ± 0.0042 | 9.96 ± 9.86 | 12.0 ± 0.41 | 3.38 |

| 17 | 0.0023 ± 0.0014 | 0.00090 ± 0.00084 | 0.0028 ± 0.0029 | 0.0015 ± 0.00093 | 0.00095 ± 0.00037 | 0.10 ± 0.097 | 0.072 ± 0.063 | 8.57 ± 9.92 | 0.60 ± 0.28 | 4.11 |

| acyclovir | 0.47 ± 0.21 | >88.8 | 0.34 ± 0.090 | 2.84 | 54.8 ± 17.08 | NDe | NDe | >88.8 | >444 | |

| penciclovir | 0.48 ± 0.41 | >79.0 | 0.84 ± 0.51 | NDe | NDe | NDe | NDe | >79.0 | >395 | |

| brivudine | 0.043 ± 0.027 | >30.0 | >30.0 | 0.053 ± 0.052 | 22.1 ± 25.5 | NDe | NDe | >30.0 | >300 | |

| anciclovir | 0.057 ± 0.053 | >29.5 | 0.051 ± 0.048 | NDe | NDe | 7.41 ± 4.94 | 3.31 ± 1.01 | >39.2 | >319 | |

| cidofovir | 4.18 ± 3.22 | 1.95 ± 0.82 | 2.73 ± 1.10 | NDe | NDe | 1.60 ± 0.87 | 0.84 ± 0.21 | >71.6 | >358 | –2.39 |

Effective concentration required to reduce virus-induced cytopathicity (HSV and HCMV) or plaque formation (VZV) by 50%.

Minimum concentration required to cause a microscopically detectable alteration of cell morphology.

Cytotoxic concentration required to reduce cell viability by 50%.

cLogP values were calculated using ChemBioDraw Ultra version 14.0 from CambridgeSoft.

Not determined.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of (S)-cHPMPA Phosphonamidates 10–16.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) l-amino acid (di)amyl ester HCl salts 9a–g (see the Supporting Information), PhOH, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, PPh3, Et3N, Pyr, 60 °C, 12 h; (ii) TCA (6% in DCM), rt, 2 h, 28–35% over two steps.

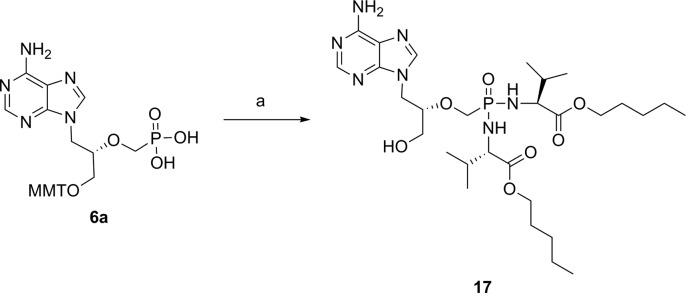

Phosphonobisamidate 17 was also prepared using a slightly modified protocol from the parent nucleoside phosphonate 6a and featured l-valine as amino acid motifs (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of (S)-cHPMPA Phosphonobisamidate 17.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) l-valine amyl ester HCl salt 9e, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, PPh3, Et3N, Pyr, 60 °C, 12 h; (ii) TCA (6% in DCM), rt, 2 h, 32% over two steps.

Compounds 8a/b and 10–16 were evaluated for their antiviral activity against HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV [strains (TK+) Oka and thymidine kinase deficient (TK–) 07-1], and HCMV (strains AD-169 and Davis) in human embryonic lung (HEL) cells (Table 1). In parallel, the potential toxic effects were assessed on the same cell line. The (S)-enantiomer of cHPMPA diamyl aspartate phosphonoamidate prodrug 8a showed good activity against HSV, VZV, and HCMV with EC50 values in the 0.0009–0.0032, 0.0014–0.0015, and 0.009–0.027 μM ranges, respectively. On the other hand, the (R)-counterpart 8b displayed 24- to 180-fold decreased potency. Notably, all other tested analogues 10–16 displayed very potent anti-HSV, VZV, and HCMV activity. In particular, (S)-Phe-cHPMPA (10), (S)-Glu-cHPMPA (13), (S)-Val-cHPMPA (14), (S)-Leu-cHPMPA (15), and (S)-Ile-cHPMPA (16) emerged as the most potent compounds against HSV with EC50 values consistently in the 0.0012–0.0042 μM range. Good selectivity indexes (SI: CC50/EC50 > 4400) were obtained, in particular, for (S)-Phe-cHPMPA (10) and (S)-Ile-cHPMPA (16). Compounds 10–16 proved also very potent against all VZV and HCMV strains with EC50 values in the 0.00045–0.0043 and 0.0038–0.064 μM range, respectively. Among these compounds, (S)-Ile-cHPMPA (16) emerged as the most selective one with SI’s of 20000 and 1800 in the anti-VZV and anti-HCMV assays, respectively.

When compared to cidofovir, all compounds displayed a dramatically improved antiviral activity. This can be explained by an improved cellular permeability, due to an increased lipophilicity, as evidenced by the clogP values. Importantly, HPMPA prodrugs proved more potent than the reference drugs, i.e., acyclovir (HSV and VZV) and ganciclovir (HCMV). Furthermore, the newly synthesized compounds were equally active against TK+ and TK– HSV and VZV strains.

The main drawback of these amidate prodrugs of (S)-cHPMPA is that diastereomeric mixtures are formed due to the chirality of the phosphorus atom. To avoid the tedious separation of both diastereomers, the symmetrical phosphonodiamidate prodrug 17 was also evaluated. This compound was endowed with potent anti-HSV and VZV activity, displaying EC50 values in the range of 0.0009–0.0015 μM, along with decreased CC50 values. With regard to the anti-HCMV activity, compound 17 was less potent than the (S)-cHPMPA prodrugs, with EC50 values in the range of 0.072–0.10 μM.

The amidate prodrugs of (S)-cHPMPA showed promising in vitro antiviral activity against HSV, VZV, and HCMV. However, to achieve antiviral efficacy in vivo, such prodrugs must be stable during the absorption and distribution processes, since their partial or full hydrolysis before reaching the target organs may reduce their antiviral effect. To exert such effect, the phosphonoamidate prodrugs must penetrate the target cells efficiently, and undergo intracellular metabolism, yielding HPMPA, which is further phosphorylated to the pharmacologically active diphosphophosphonate analogue. The intracellular activation pathway of ProTides has been extensively studied.20−23 McGuigan et al. proposed an activation route for phosphorodiamidates.24 It has been reported that cHPMPC is intracellularly converted to cidofovir by a cyclic CMP phosphodiesterase.25

The in vitro stability of three representative prodrugs (8a, 15, and 17) in human plasma and human liver microsomes was investigated (Table 2). (S)-Leu-cHPMPA (15) was found to be stable in human plasma with a t1/2 value of almost 1.5 h, whereas the half-life of prodrug 8a (bearing an aspartic acid as amino acid motif) was only 22 min. The phosphonobisamidate prodrug of HPMPA (17) displayed high stability in human plasma (t1/2 > 2 h). On the other hand, very short half-lives of prodrugs 8a and 17 (t1/2 = 4 min) were observed in human liver microsomes, suggesting that they are quickly metabolized in liver cells. The microsomal stability of prodrug 15 was slightly better with a t1/2 value of 16 min, indicating that the structural variation of the amino acid moiety offers the possibility to improve the microsomal stability.

Table 2. Metabolic Stability of Prodrugs 8a, 15, and 17 in Human Plasma and Human Liver Microsomes.

Results are the mean of two independent experiments.

In summary, the synthesis of amidate prodrugs of cHPMPA was performed using an aryloxyphosphonamidate as key intermediate. In addition, one phosphonobisamidate prodrug of (S)-HPMPA was synthesized. All prodrugs based on (S)-HPMPA exhibited potent antiviral activity against HSV, VZV, and HCMV with EC50 values in the low nanomolar range, whereas a prodrug derived from (R)-HPMPA resulted much less active. Three representative prodrugs were tested for metabolic stability in the presence of human plasma and human liver microsomes. (S)-Leu-cHPMPA 15 and the phosphonobisamidate prodrug of HPMPA 17 were found to be stable in human plasma with t1/2 values exceeding 1 h. On the other hand, all prodrugs underwent fast metabolism in the presence of human liver microsomes. Further chemistry could focus on structural variations of the amino acid side chain and ester moieties in order to further optimize the prodrug structure in function of antiviral activity and metabolic stability in plasma and microsomes.

Acknowledgments

M.L. acknowledges the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for funding and FWO for financial support. The authors are grateful to Ellen De Waegenaere for excellent technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- VZV

varicella zoster virus

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- HHV

human herpesvirus

- cHPMPC

cyclic cidofovir

- TAF

tenofovir alafenamide

- TDF

tenofovir disoproxil

- HPMPA

1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine

- HPMPC

1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine

- TMSBr

bromotrimethylsilane

- NaH

sodium hydride

- HEL

human embryonic lung

- TK

thymidine kinase

- Phe

phenylalanine

- Glu

glutamic acid

- Val

valine

- Leu

leucine

- Ile

isoleucine

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00079.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hayward G. S.; Ambinder R.; Ciufo D.; Hayward S. D.; LaFemina R. L. Structural organization of human herpesvirus DNA molecules. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1984, 83, S29–S41. 10.1038/jid.1984.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir J. P. Genomic organization and evolution of the human herpesviruses. Virus Genes 1998, 16, 85–93. 10.1023/A:1007905910939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clercq E. D. Antivirals for the treatment of herpesvirus infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1993, 32, 121–132. 10.1093/jac/32.suppl_A.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E.; Neyts J. Antiviral agents acting as DNA or RNA chain terminators. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009, 189, 53–84. 10.1007/978-3-540-79086-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrouk K.; Piret J.; Boivin G. Herpesvirus DNA polymerases: structures, functions and inhibitors. Virus Res. 2017, 234, 177–192. 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E.; Sakuma T.; Baba M.; Pauwels R.; Balzarini J.; Rosenberg I.; Holý A. Antiviral activity of phosphonylmethoxyalkyl derivatives of purine and pyrimidines. Antiviral Res. 1987, 8, 261–272. 10.1016/S0166-3542(87)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E.; Holý A.; Rosenberg I.; Sakuma T.; Balzarini J.; Maudgal P. C. A novel selective broad-spectrum anti-DNA virus agent. Nature 1986, 323, 464–467. 10.1038/323464a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei G.; Snoeck R.; Schols D.; Goubau P.; Desmyter J.; De Clercq E. Comparative activity of selected antiviral compounds against clinical isolates of human cytomegalovirus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1991, 10, 1026–1033. 10.1007/BF01984924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Therapeutic potential of HPMPC as an antiviral drug. Rev. Med. Virol. 1993, 3, 85–96. 10.1002/rmv.1980030205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snoeck R.; Schols D.; Andrei G.; Neyts J.; De Clercq E. Antiviral activity of anti-cytomegalovirus agents (HPMPC, HPMPA) assessed by a flow cytometric method and DNA hybridization technique. Antiviral Res. 1991, 16, 1–9. 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90053-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger N.; Hitchcock M.; Chen M. S.; Barkhimer D. B.; Cundy K. C.; Kent K. M.; Lacy S. A.; Lee W. A.; Li Z.-H.; Mendel D. B. 1-[((S)-2-hydroxy-2-oxo-1, 4, 2-dioxaphosphorinan-5-yl) methyl] cytosine, an intracellular prodrug for (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) cytosine with improved therapeutic index in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 2387–2391. 10.1128/AAC.38.10.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L. W.; Sala-Rabanal M.; Krylov I. S.; Serpi M.; Kashemirov B. A.; McKenna C. E. Serine side chain-linked peptidomimetic conjugates of cyclic HPMPC and HPMPA: Synthesis and interaction with hPEPT1. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2010, 7, 2349–2361. 10.1021/mp100186b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova V. M.; Serpi M.; Krylov I. S.; Peterson L. W.; Breitenbach J. M.; Borysko K. Z.; Drach J. C.; Collins M.; Hilfinger J. M.; Kashemirov B. A. Tyrosine-based 1-(S)-[3-hydroxy-2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl] cytosine and-adenine ((S)-HPMPC and (S)-HPMPA) prodrugs: Synthesis, stability, antiviral activity, and in vivo transport studies. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5680–5693. 10.1021/jm2001426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehellou Y.; Balzarini J.; McGuigan C. Aryloxy phosphoramidate triesters: a technology for delivering monophosphorylated nucleosides and sugars into cells. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 1779–1791. 10.1002/cmdc.200900289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Dumbre S. G.; Pannecouque C.; Huang C.; Ptak R. G.; Murray M. G.; De Jonghe S.; Herdewijn P. Amidate prodrugs of deoxythreosyl nucleoside phosphonates as dual inhibitors of HIV and HBV replication. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9513–9531. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M.; Groaz E.; Andrei G.; Snoeck R.; Kalkeri R.; Ptak R. G.; Hartman T.; Buckheit R. W. Jr; Schols D.; De Jonghe S. Expanding the antiviral spectrum of 3-fluoro-2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: diamyl aspartate amidate prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 6220–6238. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti M.; Maiti M.; Rozenski J.; De Jonghe S.; Herdewijn P. Aspartic acid based nucleoside phosphoramidate prodrugs as potent inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5158–5174. 10.1039/C5OB00427F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A.; Khanna G. R.; Krishnaji T.; Ramu R. Lipase-mediated resolution of 3-hydroxy-4-trityloxybutanenitrile: synthesis of 2-amino alcohols, oxazolidinones and GABOB. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 1281–1289. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman R. L.; Ray A. S.; Hui H. C.; Zhang L.; Birkus G.; Boojamra C. G.; Desai M. C.; Douglas J. L.; Gao Y.; Grant D. Discovery of GS-9131: Design, synthesis and optimization of amidate prodrugs of the novel nucleoside phosphonate HIV reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitor GS-9148. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 3606–3617. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertusati F.; Serpi M.; McGuigan C. Medicinal chemistry of nucleoside phosphonate prodrugs for antiviral therapy. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2012, 22, 181–203. 10.3851/IMP2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groaz E.; Herdewijn P. Nucleoside phosphate-conjugates come of age: Catalytic transformation, polymerase recognition and antiviral properties. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 3980–3990. 10.2174/092986732234151119155207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derudas M.; Carta D.; Brancale A.; Vanpouille C.; Lisco A.; Margolis L.; Balzarini J.; McGuigan C. The application of phosphoramidate protide technology to acyclovir confers anti-HIV inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5520–5530. 10.1021/jm9007856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan C.; Murziani P.; Slusarczyk M.; Gonczy B.; Vande Voorde J.; Liekens S.; Balzarini J. Phosphoramidate ProTides of the anticancer agent FUDR successfully deliver the preformed bioactive monophosphate in cells and confer advantage over the parent nucleoside. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7247–7258. 10.1021/jm200815w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan C.; Madela K.; Aljarah M.; Bourdin C.; Arrica M.; Barrett E.; Jones S.; Kolykhalov A.; Bleiman B.; Bryant K. D. Phosphorodiamidates as a promising new phosphate prodrug motif for antiviral drug discovery: application to anti-HCV agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8632–8645. 10.1021/jm2011673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendel D. B.; Cihlar T.; Moon K.; Chen M. S. Conversion of 1-[((S)-2-hydroxy-2-oxo-1, 4, 2-dioxaphosphorinan-5-yl) methyl] cytosine to cidofovir by an intracellular cyclic CMP phosphodiesterase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.