Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a lethal fibrotic lung disease in adults with limited treatment options. Autophagy and the unfolded protein response (UPR), fundamental processes induced by cell stress, are dysregulated in lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells from humans with IPF. Human primary cultured lung parenchymal and airway fibroblasts from non-IPF and IPF donors were stimulated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) with or without inhibitors of autophagy or UPR (IRE1 inhibitor). Using immunoblotting, we monitored temporal changes in abundance of protein markers of autophagy (LC3βII and Atg5-12), UPR (BIP, IRE1α, and cleaved XBP1), and fibrosis (collagen 1α2 and fibronectin). Using fluorescent immunohistochemistry, we profiled autophagy (LC3βII) and UPR (BIP and XBP1) markers in human non-IPF and IPF lung tissue. TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 and fibronectin protein production was significantly higher in IPF lung fibroblasts compared with lung and airway fibroblasts from non-IPF donors. TGF-β1 induced the accumulation of LC3βII in parallel with collagen 1α2 and fibronectin, but autophagy marker content was significantly lower in lung fibroblasts from IPF subjects. TGF-β1-induced collagen and fibronectin biosynthesis was significantly reduced by inhibiting autophagy flux in fibroblasts from the lungs of non-IPF and IPF donors. Conversely, only in lung fibroblasts from IPF donors did TGF-β1 induce UPR markers. Treatment with an IRE1 inhibitor decreased TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 and fibronectin biosynthesis in IPF lung fibroblasts but not those from non-IPF donors. The IRE1 arm of the UPR response is uniquely induced by TGF-β1 in lung fibroblasts from human IPF donors and is required for excessive biosynthesis of collagen and fibronectin in these cells.

Keywords: IRE1, pulmonary fibrosis, spliced XBP1, transforming growth factor-β1

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive restrictive lung disease with a high mortality rate and median survival of 2.5 yr after initial diagnosis (39, 52). Precise triggers are unknown but IPF may be initiated by repetitive damage to the alveolar epithelium that can lead to uncontrolled wound repair orchestrated by lung fibroblasts. Recent reports suggest that the homeostatic cellular pathways, autophagy, and the unfolded protein response (UPR) may modulate IPF pathogenesis (3, 43).

Autophagy mitigates the effects of cellular stress, delivering damaged or improperly processed proteins and organelles to lysosomes for degradation, thereby supplying metabolic fuel, in particular during periods of insufficient energy supply (16, 25). Excessive autophagy can initiate programmed cell death. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) orchestrates protein folding, but when the need for proteins exceeds the capacity for protein synthesis, the UPR is induced; this triggers ER stress cascades that foster effective cellular processing of newly translated proteins and restore ER homeostasis (32). If the UPR fails to restore protein processing homeostasis, it can drive signaling that leads to apoptotic cell death that prevents excessive tissue damage (56, 60).

Araya et al. (3) recently showed that insufficient activation of autophagy may underpin cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21)-regulated senescence in airway epithelial cells from IPF donors. Autophagy inhibition has also been associated with myofibroblast phenoconversion (21), a response associated with increased synthesis of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in response to transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (3). Reduced levels of autophagy markers are evident in whole lung cell from IPF patients, although no specific mechanism for this has been definitively identified (41, 43). Interestingly, markers of UPR also appear to be increased in lung tissue from IPF patients, being chiefly localized to the alveolar epithelium (32). As UPR activation may induce apoptosis (32), this association could underpin the scarring process in the alveolar epithelium in the IPF lung (10). However, there remains a significant need to decipher the interplay between these process in pathophysiology; moreover, their roles in other structural cells of lung, chiefly fibroblasts that orchestrate tissue remodeling, have not been clarified. Recent evidence indicates that FoxO3a, a forkhead family of transcription factors characterized by a distinct forkhead DNA-binding domain, decreases expression of LC3βII and reduces autophagy flux in lung fibroblasts from IPF donors, suggesting the existence of a complex regulator network of trophic, survival, and secretory functions in these cells (27).

The TGF-β1 superfamily has an essential role in lung disease associated with tissue and ECM remodeling, including IPF (12, 23, 28, 35, 51, 55, 57). TGF-β1 can promote autophagy in different cell types, including human heart and lung fibroblasts, a response that we have shown promotes the synthesis of ECM proteins (9, 14, 15, 46). There is no direct evidence for TGF-β1-associated modulation of the UPR in lung cells, despite there being evidence linking UPR activation with lung fibrosis (10, 32). Here we test the hypothesis that there are concomitant and interconnected roles for autophagy and UPR in TGF-β1-induced ECM protein biosynthesis in primary cultured human lung (HLFs) and airway fibroblasts (HAFs) from non-IPF and IPF donors. We monitored temporal changes in abundance of UPR and autophagy markers in response to TGF-β1 and profiled marker coexpression in IPF and non-IPF lung tissues. Furthermore, we compared the requirement for autophagy and the UPR in TGF-β1-induced extracellular protein synthesis using selective autophagy and UPR inhibitors. Our data reveal an essential role of UPR and autophagy in the profibrotic response of HLFs and that they differentially contribute to disparate responses of cells from human non-IPF and IPF subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Cell culture plastic ware and cell culture media were obtained from VWR (Mississauga, Canada). Bafilomycin-A1 (Baf-A1), rabbit anti-human/mouse/rat LC3βII (L8918, 1:3,000), anti-mouse IgG (A8924, 1:3,000), and anti-rabbit IgG (A6154, 1:5,000) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, CA).The IRE1-specific inhibitor (MKC8866), which inhibits both basal and thapsigargin induced splicing of XBP1 mRNA (47), was provided by Mannkind (Westlake Village, CA). MKC8866 is a member of a class of salicylaldehyde analogs, identified as inhibitors of the site-specific cleavage of several mini-XBP1 stem-loop RNAs, and inhibits XBP1 splicing in an in vivo model of acute ER stress (53). Salicylaldehyde analogs also block transcriptional upregulation of XBP1 targets and mRNAs targeted for degradation by IRE1α. Goat anti-human collagen 1α2 (sc-8786, 1:1,500), rabbit anti-human/mouse/rat fibronectin (sc-9068, 1:1,000), and mouse anti-human GAPDH (sc-69778, 1:7,000) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-human/mouse/rat Atg12 (4180, 1:1,000), rabbit anti-human/mouse GRP78 (BIP; 3177, 1:1,000), rabbit anti-human/mouse IRE1α (3294, 1:1,000), rabbit anti-human/mouse SMAD2/3 (3102, 1:1,000), and rabbit anti-human/mouse/rat phospho-SMAD2 (3101, 1:1,000) were from Cell Signaling (Whitby, Canada). Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) was purchased from R&D Biosystems (Minneapolis, MN). Primary human IPF fibroblast cultures were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

Study subjects: immunohistochemistry.

Lung parenchyma containing predominantly alveolar tissue from four IPF patients and from the Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic, University of California, Davis Medical Center (UCDMC), in Sacramento, CA were processed from surgical biopsies. Tissues were from deidentified deceased patients who were part of an IPF registry in our Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic. IPF diagnosis was confirmed based on medical history, physical examination, high-resolution computed tomography, pulmonary function tests, and diagnostic lung biopsy. In all cases, the pathological diagnosis was usual interstitial pneumonia confirmed by a licensed lung pathologist at UCDMC. For non-IPF lung tissue, lung parenchyma was obtained from macroscopically healthy segments of peripheral lung from four patients undergoing pneumonectomy or lobectomy surgery for lung cancer at the Section of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Medicine, University of Manitoba. Subjects were ex-smokers for at least 10 yr at the time of surgery, and based on preoperative lung function testing, exhibited no sign of obstructive airways disease. Informed consent and tissue acquisition were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at UCDMC and the University of Manitoba.

Non-IPF and IPF human peripheral lung and airway fibroblast cultures.

Macroscopically healthy lung specimens from non-IPF donors were obtained from patients undergoing lung resection surgery for lung cancer in the Section of Thoracic Surgery, University of Manitoba. Tissue acquisition was approved by informed consent of each donor according to protocols approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Board.

Primary HLF cultures were isolated from peripheral, subpleural lung specimens. Following removal of visceral pleura by dissection, lung material was incubated in HBSS supplemented with antibiotic/anti-mycotic (1:100) and gentamicin-A (50 µg/ml) for 60 min at 4°C. Thereafter, the tissue was minced and subjected to enzymatic dissociation (60 min, 37°C) in HBSS containing 600 U/ml collagenase I, 2 U/ml protease, 2 U/ml papain, and 3.8 mM calcium chloride. Tissue was disrupted by glass pipette trituration, debris was allowed to settle, and then the cells in the supernatant were collected by centrifugation (5 min, 800 g). The cells were redispersed in culture medium (high-glucose DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U/ml strepto-ECM, and 50 μg/ml penicillin) and then seeded in plastic culture plates (10,000 cells/cm2) and maintained in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Media were changed routinely and at confluence reseeded (1:4) into new plates. HLF phenotype was confirmed by positive immunocytochemistry for vimentin (cultures were negative for endothelial and epithelial cell markers, Von Willebrand factor, and E-cadherin, respectively; not shown). For all studies, HLFs were used at passages 3–7.

Primary cultured HAFs and lung fibroblasts were prepared as we have previously described from second to fourth generation of bronchi in macroscopically healthy segments of resected lung specimens. After microdissection to separate the submucosal compartment of the airway wall, HAFs were isolated by enzymatic dissociation using a protocol similar to that used for HLFs and that we have described previously (17–20). For all studies, HAFs were used at passages 3–7.

The IPF fibroblasts used in this study were isolated as previously described by us from lung biopsy specimens or explanted lung during lung obtained at transplantation from IPF patients (44, 45). All cells were grown and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS with antibiotic. IPF lung fibroblasts were used at passages 3–7.

TGF-β1 treatment of cell cultures.

Fibroblasts were cultured in serum-replete medium to ~80% confluency and then maintained in serum-deficient medium supplemented with 1% insulin/transferrin/selenium for 48 h, thus providing and environment that supports low levels of basal autophagy in IPF and non-IPF fibroblasts and enables detection of the net effect of TGF-β1 on IPF fibroblasts in absence of FBS growth factors (15). Thereafter, cultures were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml for up to 120 h). In experiments involving inhibitors (Baf-A1 or IRE1 inhibitor, 10 µM), the cells were pretreated with inhibitor (4 h) before TGF-β1 exposure. Cells were 100% confluent at the time they were harvested. Importantly, for studies using Baf-A1, in pilot studies we determined the maximum concentration that can be used without inducing marked cell death in the time span of the experiments we conducted.

Immunoblotting.

Non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts were treated with the aforementioned dose of TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of inhibitors (Baf-A1 or IRE1 inhibitor) at each time point, and cells were collected in NP-40 lysis buffer. Western blotting was used to detect collagen 1α2, fibronectin, LC3βII, Atg5-12, IRE1α, Atg5-12, XBP1, and GAPDH. Briefly, cells were washed and protein extracts prepared in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5% NP-40 (Tergitol-type NP-40), 0.5 mM PMSF, 100 µM β-glycerol-3-phosphate, and 0.5% protease inhibitor cocktail]. After centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min, the protein content in the supernatant was determined by the Lowry protein assay, and proteins were then size-fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nylon membranes under reducing conditions. After membranes were blocked with nonfat dried milk and Tween 20, blots were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was incubated for 1 h at room temperature, and blots were then developed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) (18–20).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

IPF cells were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml), IRE1 inhibitor (10 μM), and TGF-β1 and IRE1 inhibitor and harvested after 96 h, RNA extraction was done using Qiagen RNeasy kit (Cat. No. 74104) based on the manufacturer's protocol, and cDNA was synthesized by Invitrogen kit (Superscript II reverse transcriptase; Cat. No. 18064014) using the kit protocol.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Bio-Rad kit (Cat. No. 172–5200) and using the recommended protocol by the manufacturer. Briefly, a mixture containing 10 µl SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix, 500 nM of each of the primers, and 5 ng of cDNA was prepared and the gene segments of interest were amplified using a CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The following protocol was used for gene amplification: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, and annealing and elongation at 60°C for 30 s. The TATA box binding protein (TBP) gene expression was used as the reference gene. Primer sequences were as follows: fibronectin forward: 5′-GCC CAT AGC TGA GAA GTG TT-3′; fibronectin reverse: 5′-TTC TCC CAG GCA AGT ACA ATC-3′; TBP forward: 5′ GGT GCT AAA GTC AGA GCA GAA-3′; and TBP reverse: 5′-CAA GGG TAC ATG AGA GCC ATT A-3′. All PCR reactions were run in triplicate. The ratio of fibronectin gene expression level was calculated by the ΔΔCT method.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Sections of 4 μm were prepared from representative paraffin blocks of human lung samples. Sections were then deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and a series grade of alcohol. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed using a standard protocol. For immunohistochemistry staining, heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed by placing the slides in a pressure cooker with citrate buffer (0.1 M citric acid and 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 6.0) in a Coplin Jar for 15 min. After cooling to room temperature, sections were stained for LC3βII, BIP, and XBP1 expression using a standard procedure by using specific antibodies against LC3βII (Cat. No. 18725-1-AP; Proteintech), BIP (Cat. No. ab21685; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and XBP1 (Cat. No. ab37152; Abcam) diluted in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C in humidified chamber. Slides were washed thoroughly with 1× PBS, and primary antibody was detected by using corresponding secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI dye followed by mounting using ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) Fluorescent images were captured with a Leica CTRMIC 6000 confocal microscope in conjunction with a Hamamatsu C910013 spinning-disk camera (Leica Microsystems, Concord, ON, Canada) (13). Laser intensity and detector sensitivity settings remained constant for all image acquisitions within a respective experiment. Images were later analyzed using Volocity software (Perkin-Elmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada).

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SD, and statistical differences were evaluated by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, using GraphPad Prism 5.0. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For all experiments, data were collected in triplicate from at least three cell lines unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Elevated TGF-β1-induced UPR and ECM synthesis but reduced autophagy in IPF lung fibroblasts.

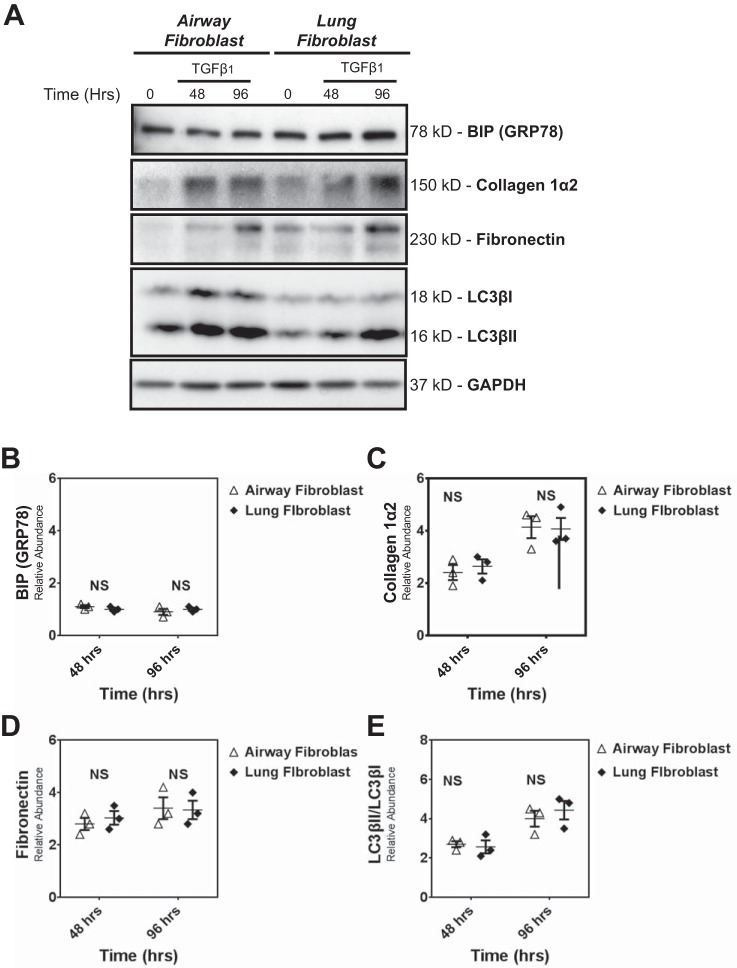

We first compared the response to TGF-β1 of HLFs and HAFs obtained from non-IPF donors, measuring abundance of protein markers for UPR (BIP), autophagy (LC3βII), and fibrosis (collagen 1α2 and fibronectin) (Fig. 1A). We found that UPR, autophagy, and profibrotic responses were the same in fibroblasts from lung parenchyma or the airways (Fig. 1, B–E) (P > 0.05). Thus, for subsequent studies to compare the response of IPF and non-IPF cells, we used both non-IPF HAFs and HLFs.

Fig. 1.

Human airway and lung fibroblasts isolated from nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (non-IPF) lungs do not differ in transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-induced fibrotic response, unfolded protein response (UPR), and autophagy activity. A: primary human non-IPF airway and lung fibroblasts (passages 3–6) were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) (0–96 h). Cell lysates were collected and the abundance of UPR (BIP), autophagy (LC3βII), and profibrotic proteins (collagen 1α2 and fibronectin) were assessed by Western blot. Protein loading was confirmed using GAPDH. A–E are representative of experiments performed on 3 different primary non-IPF airway and lung fibroblast cultures (n = 3). No differences (P > 0.05) were detected in UPR (B), fibrotic (C and D), and autophagy (E) markers between airway and lung fibroblasts. B–E: dot plots of data from individual experiments. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. NS, no significant difference.

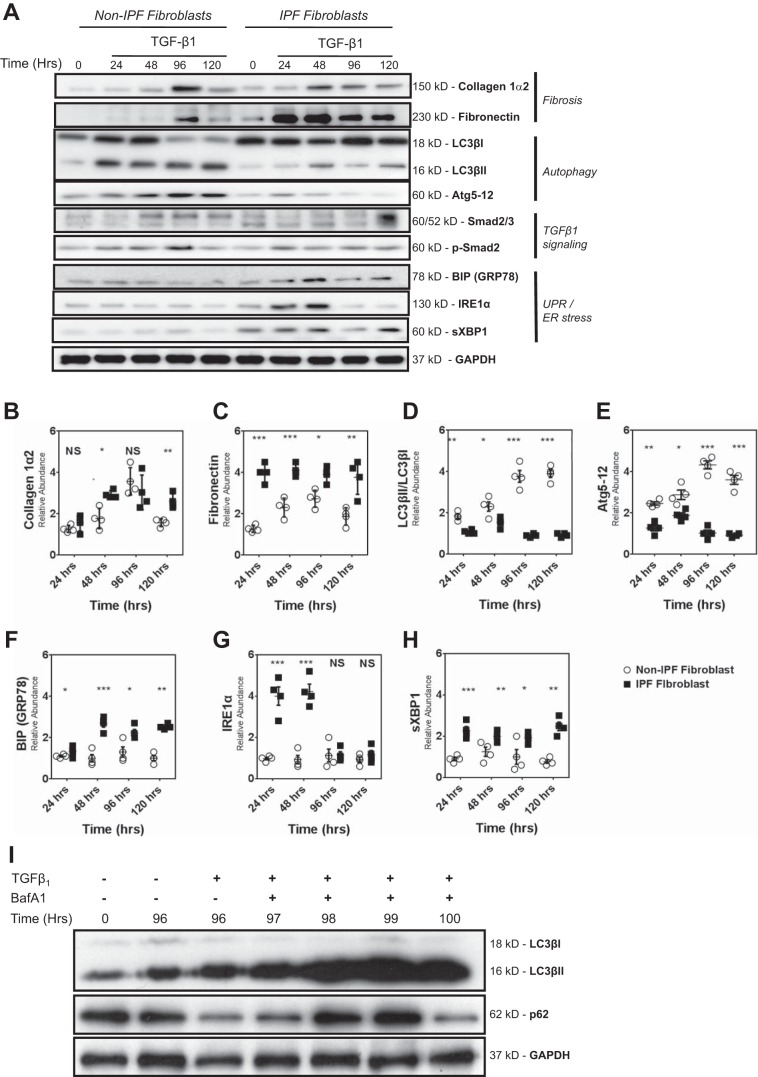

We next compared the temporal response to TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) of lung fibroblasts from IPF donors and non-IPF donors using immunoblotting to measure changes in the abundance of ECM proteins (collagen 1α2 and fibronectin), autophagy markers (LC3βII, Atg5-12 complex), and UPR hallmarks [BIP/GRP78, IRE1α, and spliced XBP1 (sXBP1)]. Although there was no difference in baseline (pre-TGF-β1) abundance, we did measure a significantly higher induction of fibronectin and of collagen 1α2 in TGF-β1-treated IPF lung fibroblasts (Fig. 2, A–C). Interestingly, for this set of studies, we repeatedly observed a spike in collagen 1α2 and fibronectin 96 h after TGF-β1 exposure in non-IPF fibroblasts. The abundance of both BIP/GRP78 and IRE-1α was significantly higher at baseline in IPF lung fibroblast cultures (P < 0.001). Moreover, TGF-β1 stimulation provoked a greater accumulation of these UPR markers in IPF fibroblasts, although hyperelevation of IRE1α was only sustained through 48 h (Fig. 2, A, F, G, and H). Conversely, while markers for autophagy were similar between cultures at baseline, they were significantly lower at all time points after TGF-β1 exposure in IPF fibroblasts compared with non-IPF HAFs (Fig. 2, A, D, and E). We also confirmed autophagy flux in IPF fibroblasts, using 100 nM Baf-A1 to reveal enhanced LC3βII accumulation and p62 degradation in the presence of TGF-β1 (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2.

Fibroblasts isolated from non-IPF lungs and those with IPF donors differ in TGF-β1-induced fibrotic response, UPR, and autophagy activity. A: primary human non-IPF fibroblast and IPF fibroblasts (passages 3–6) were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) (0–120 h). Cell lysates were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the expression of UPR [BIP, IRE1α, and sliced XBP1 (sXBP1)], autophagy (LC3βII and Atg5-12), and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (collagen 1α2 and fibronectin), as well as Smad signaling effectors were assessed by Western blot analysis. Protein loading was confirmed using GAPDH. Data in A represent experiments performed on 4 different primary non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts. B and C: densitometry showed that TGF-β1 stimulation led to an increase in abundance of collagen Iα2 and fibronectin that was greater in IPF fibroblasts compared with non-IPF fibroblasts. D and E: abundance of autophagy proteins LC3βII/LC3βI and Atg5-12 following TGF-β1 stimulation was significantly lower in IPF fibroblasts as compared with non-IPF fibroblasts. F–H: TGF-β1 stimulation also resulted in significant accumulation of UPR proteins (BIP, IRE1α, and sXBP), which was greater in IPF fibroblasts compared with non-IPF fibroblasts. Data in B–H are shown in dot plots of from 4 individual experiments using different IPF and non-IPF samples. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean ± SE. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01: *P < 0.05; NSP > 0.05, no significant difference. I: primary human IPF fibroblasts (passages 2–3) were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 96 h and then treated with bafiloECM A1 (Baf-A1; 100 nM) for up to 4 h more. LC3βII accumulation and p62 degradation were measured using GAPDH as protein loading confirmed.

Autophagy is necessary for TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts.

We measured the impact of chemical inhibition of autophagy flux, using Baf-A1, on TGF-β1-induced synthesis of collagen 1α2 (Fig. 3, A–F). Our results show that autophagy is necessary for the TGF-β1-induced production of this ECM protein in non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts. However, the degree of autophagy was significantly lower in IPF fibroblasts as compared with non-IPF fibroblasts (Fig. 2, A, C, D, and F). Inhibition of autophagy flux in non-IPF fibroblasts and IPF fibroblasts significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 synthesis (Fig. 3, B and E). These data suggest that while IPF fibroblasts have lower autophagy markers compared with non-IPF fibroblasts, autophagy is necessary for TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in both non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts.

Fig. 3.

Autophagy is required for TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in both non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts. A: primary human non-IPF fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the chemical inhibitors of autophagy (Baf-A1; 10 nM) for the indicated times. A representative blot from 4 different primary non-IPF fibroblasts (n = 4) is shown. B and C: densitometry analysis of different IPF and non-IPF fibroblasts confirmed that the inhibition of autophagy significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced collagen biosynthesis in human non-IPF fibroblasts while there is not any significant difference in LC3βII between TGF-β1 and TGF-β1 + Baf-A1 group. Densitometry data are normalized to time matched controls grown in insulin/transferrin/selenium medium. Data are shown in dot plots of from 4 individual experiments using different cell lines. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. ***P < 0.001; NSP > 0.05, no significant difference. D: primary human IPF fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the autophagy chemical inhibitor bafiloECM A1 (10 nM) for the indicated time points. Immunoblots show the expression of collagen 1α2 and LC3βII. Data in D represent examples of 4 different primary IPF fibroblasts (n = 4). E and F: densitometry analysis confirmed that autophagy inhibition significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced collagen biosynthesis in human IPF fibroblasts while there is not any significant difference in LC3βII between TGF-β1 and TGF-β1 + Baf-A1 group. Densitometry data are normalized to time-matched controls in ITS medium. Data are shown in dot plots of from 4 individual experiments using different cell lines. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. *** P < 0.001; NSP > 0.05. no significant difference.

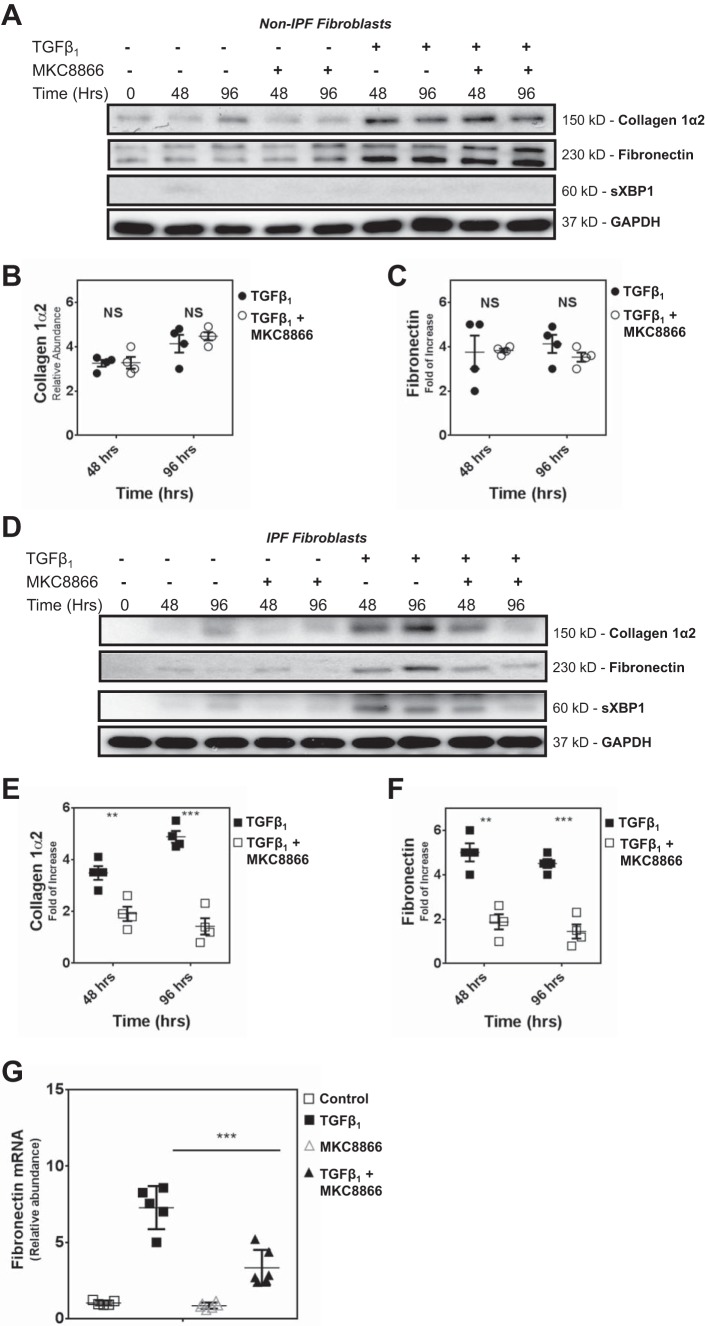

UPR induction is required for TGF-β1-induced ECM synthesis in IPF lung fibroblasts.

In non-IPF HAFs, we used immunoblotting to track the effects of TGF-β1 exposure on the induction of sXBP1, a marker for UPR, and found that the cells exhibited no evidence of UPR (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we show that a specific IRE1 inhibitor (MKC8866) that blocks XBP1 splicing (7) had no impact on TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 and fibronectin biosynthesis in non-IPF fibroblasts (Fig. 4, A–C). In striking contrast, TGF-β1 treatment induced significant XBP1 splicing in IPF fibroblasts (Fig. 4D). Moreover, cotreatment with MKC8866 prevented sXBP1 formation, an effect that correlated with ablation of excessive TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 and fibronectin synthesis in IPF lung fibroblasts (Fig. 4, D–F). Quantitative PCR also showed that IRE1 inhibition prevents TGF-β1-induced accumulation of fibronectin mRNA in IPF fibroblasts (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these data indicate that in IPF lung fibroblasts, TGF-β1 uniquely induces excess UPR and biosynthesis of collagen 1α2 and fibronectin, and that increased XBP1 splicing is necessary for TGF-β1-induced production of ECM protein.

Fig. 4.

XBP splicing is required for TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in primary human IPF, but not non-IPF, fibroblasts. A: primary human non-IPF fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 (10 μM) for the indicated time points. The representative immunoblot shows the abundance of collagen 1α2, fibronectin, and sXBP in 4 different primary non-IPF fibroblasts. B and C: densitometry analysis (n = 4) confirmed that MKC8866 did not significantly reduce TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 or fibronectin biosynthesis in non-IPF human fibroblasts. Data are shown in dot plots of from 4 individual experiments using different cell lines. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. NSP > 0.05, no significant difference. D: primary human IPF fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of IRE1 inhibitor (10 μM) for the indicated time points. Immunoblots are arranged to show expression of collagen 1α2, fibronectin and sXBP. The immunoblot is representative of experiments performed on 4 different primary IPF fibroblasts (n = 4). E and F: densitometry analysis confirmed that treatment of IPF fibroblasts with IRE1 inhibitor significantly reduced TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α2 and fibronectin biosynthesis. Data are shown in dot plots of from 4 individual experiments using different cell lines. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01. G: primary human IPF fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of IRE1 inhibitor (10 μM) for 96 h. For a baseline control, cells were maintained in serum- and TGF-β1-deficient media. Quantitative PCR showed that MKC8866 significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced fibronectin mRNA accumulation in IPF fibroblasts. The experiments were performed in duplicate on 2 different primary IPF fibroblast cell lines. Data are shown in dot plots from each experiment. The horizontal line in each column represents the mean, with error bars showing SE. ***P < 0.001.

Relative contributions of autophagy and UPR in IPF vs. non-IPF lungs.

Our data reveal unique and potentially interconnected roles for autophagy and UPR in determining the response to TGF-β1 in IPF lung fibroblasts. To decipher the interplay between both pathways in these cells, we measured the effects of IRE1 inhibition on autophagy and, vice versa, the effect of blocking autophagy flux on UPR in TGF-β1-exposed IPF lung fibroblasts (Fig. 5). Interestingly, in the presence of TGF-β1, we observed that IRE1 inhibition had little or no effect on TGF-β1-induced increased autophagy (LC3βII accumulation and p62 degradation), whereas suppression of autophagy flux with Baf-A1 led to an increase in the accumulation of BIP in the presence or absence of TGF-β1.

Fig. 5.

Autophagy flux inhibition and IRE1α inhibition modulates UPR and autophagy in IPF fibroblasts. Primary human IPF fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of bafilomycin-A1 (10 nM) or IRE1 inhibitor MKC8866 (10 μM) for 48 or 96 h. Immunoblots show abundance of autophagy (LC3βII, p62) and UPR (BIP) markers. The blot shown is representative of experiments performed on 2 different primary IPF fibroblast cell lines.

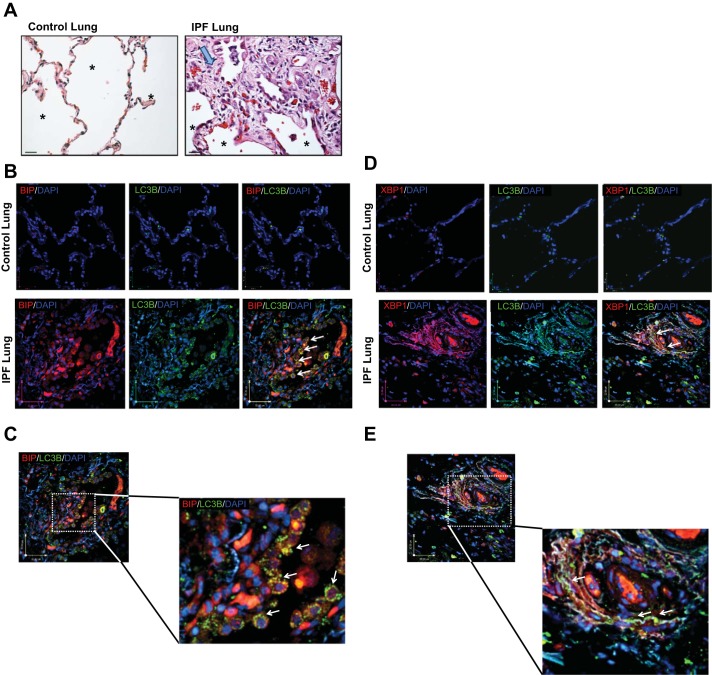

We used immunohistochemistry to evaluate the distribution of autophagy and UPR marker proteins (LC3βII, sXBP1, and BIP) in non-IPF and IPF lung tissue; the latter exhibiting histopathology consistent with IPF, with evidence of fibrotic lesions replete with fibroblasts and significant loss of alveolar structure (Fig. 6A). The diagnosis of UIP for IPF lungs was independently verified by a lung pathologist. Using confocal microscopy, we observed robust labeling for all autophagy and UPR markers in regions of fibrotic foci in IPF lungs, whereas in lung parenchyma from non-IPF donors there was a paucity of labeling for LC3βII, sXBP1, and BIP (Fig. 6, B–E). Notably in IPF lesions we observed evidence of punctate LC3βII distribution, an indicator of cells undergoing autophagy flux. Indeed, puncta of LC3βII were evident in both epithelial and mesenchymal cells. With respect to UPR markers, BIP and nuclear sXBP1 were evident in both epithelial and mesenchymal cells in IPF lung lesions. Double labeling revealed that LC3βII-positive cells were also positively labeled for BIP and sXBP1 in IPF lung tissue.

Fig. 6.

Autophagy and UPR proteins colocalize and are simultaneously increased in IPF lungs. A: representative histological images of peripheral parenchymal non-IPF and IPF lung tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin. IPF lung tissue showing fibroblastic foci (large arrow). Alveolar structures are indicated by an asterisk. Magnification: ×40. B and C: immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of control and IPF lung tissue for LC3βII (green), BIP (red), and DAPI (blue). Punctate foci of LC3βII are indicated with white arrows. D and E: confocal images of control and IPF lung tissue for LC3βII (green), XBP (red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars are included in each image.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we have investigated the association and contribution of autophagy and UPR in TGF-β1-induced profibrotic effects in fibroblasts from the lungs of human non-IPF and IPF donors. We show that TGF-β1 uniquely induced accumulation of the IRE1α-activated UPR marker sXBP1 in IPF fibroblasts, whereas in non-IPF cells no UPR response was evident upon TGF-β1 exposure. Notably, we report that inhibition of IRE1 with a selective pharmacologic agent abrogates the significantly higher TGF-β1-induced synthesis of collagen 1α2 and fibronectin in IPF fibroblasts. We also demonstrate that autophagy and UPR markers are increased and colocalize to cells in fibrotic lesions in IPF donor lungs. Collectively, these data demonstrate that UPR in structural cells of the lung underpins excess ECM protein synthesis associated with human IPF.

TGF-β1 is a primary driver of tissue fibrogenesis in the lung (2, 33), heart (49, 59), kidney (4, 54), and liver (8). TGF-β1 also inhibits starvation-induced autophagy in HAFs and cells of the annulus fibrosus of intervertebral disks (42, 43). Conversely, TGF-β1 can induce autophagy in association with fibrosis in liver and kidney cells (9, 14). At present, the context- and tissue-specific role of TGF-β1 in regulating autophagy and pathogenic features associated with fibrogenesis is unclear.

Diverse results from studies that dissect the role of specific autophagy regulator (ATG) proteins confer disparate effects with respect to wound repair and tissue remodeling. In some cases, autophagy can facilitate fibrosis (9, 14), but it appears to be downregulated in IPF lungs (3, 40, 43), whereas it may be increased in asthma (46, 58). Studies of liver fibrosis indicate that chemically induced liver injury causes hepatic stellate cell activation and promotes lipid catabolism and the loss of lysosomal lipids, which reduces liver fibrosis, particularly in steatosis-related cirrhosis (26). The activation and subsequent fibrotic response in stellate cells from ATG7−/− mice were significantly decreased (26). Inhibition of autophagy with 3-methyladenine and by ATG5 or ATG7 silencing significantly reduces expression of ECM proteins, α-smooth muscle actin, and β-platelet-derived growth factor receptor in cultured stellate and mesangial cells (26). Conversely, autophagy can regulate TGF-β1-induced collagen 1α1 in kidney mesangial cells (29). This difference may be due to disparate targeting of autophagy regulators. In one study, autophagy initiation and flux were targeted by beclin1 silencing and Baf-A1 treatment (29), whereas ATG7 was silenced in another study (26). Collectively, there is significant evidence for autophagy as a regulator in fibrogenesis and that autophagy flux likely modulates TGF-β1-induced ECM protein expression. However, these associations have not been clarified in the context of lung fibrosis.

Our results show that while TGF-β1 induces autophagy in both non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts, this response is more pronounced in non-IPF fibroblasts. In addition, we demonstrate that autophagy is necessary for TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in both non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts. This is contrary to previous data showing that TGF-β1 can decrease autophagy (43). One of the major differences in our study is that we treated both non-IPF and IPF fibroblasts with TGF-β1 over a longer period of time (120 vs. 48 h) than was done previously. As had been suggested in other reports (48), it is possible that a longer duration TGF-β1 treatment may support more sustained induction of secreted proteins such as cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that influence the final autophagy response, as we may have observed.

A number of reports conclude that autophagy is not a dominant feature in human IPF (3, 43). However, our results indicate that while TGF-β1-induced autophagy is induced to a lesser degree in IPF fibroblasts compared with non-IPF fibroblasts, it is required for the profibrotic effects of TGF-β1. Autophagy is activated in cellular events that are energy demanding and functions to provide reserves to the cell (6, 11). Fibrosis requires significant energy-requiring ECM protein biosynthesis; thus it is likely that autophagy is necessary to support the production of collagen and fibronectin in both non-IPF and IPF lung fibroblasts.

We show that the response lung fibroblasts from IPF subjects to TGF-β1 is also unique in that we observe increased ER stress and UPR in association with excessive ECM protein biosynthesis. ER stress is a feature of fibro-proliferative diseases including pulmonary fibrosis, diabetic nephropathy, cardiac fibrosis, and atherosclerosis (5, 22, 24, 30). Factors involved in initiating tissue remodeling in different tissues tax ER function and can initiate UPR and the ER stress response (36). Our immunohistochemistry observations indicate that the abundance of both sXBP1 and BIP, markers of ER stress and UPR, is increased in pulmonary fibrotic lesions associated with IPF. Notably, the ER stress inducer tunicamycin exacerbates lung fibrosis in bleiomycin-challenged rats (1). Furthermore, enhanced ER stress in alveolar epithelial cells appears to be a facilitator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a process associated with pathogenesis of fibrotic diseases like IPF (38).

The mechanisms by which ER stress may predispose and promote fibrosis are unresolved. We show that TGF-β1 significantly induces UPR but only in lung fibroblasts from IPF donors. Chemical compounds such as valproate and 4-phenylbutyrate that influence ER and effectively decrease ER stress can both reduce fibro-proliferative disease states such as atherosclerosis and lung fibrosis (37) and significantly inhibit TGF-β1-induced biosynthesis of type I collagen (38). A unique and compelling finding from our work is that selective pharmacological inhibition of the IRE1α arm of UPR, which blunts XBP1 splicing, prevents the excessive profibrotic response of IPF lung fibroblasts stimulated with TGF-β1. It has been reported that XBP1 and its splice variant are significantly upregulated in scleroderma (34), and our findings support the possibility that UPR gene expression and altered XBP1 mRNA processing and splicing may be driving forces for fibrosis in systemic scleroderma and IPF (31, 32). For our studies we used MKC8866, which inhibits kinase and RNAase activity of IRE1, as well as the formation of sXBP1 (7, 47). With this approach, we show that targeting the IRE1 branch of UPR holds some potential to mitigate pathobiological aspects of lung fibrotic diseases; thus we support future basic and clinical research in this area.

In summary, we demonstrate that TGF-β1 induces higher levels of ER stress and UPR in fibroblasts from IPF patients compared with patients without IPF. Furthermore, the role of autophagy in TGF-β1-induced fibrosis is critical in IPF, despite the fact that autophagy is generally diminished in IPF fibroblasts. The fibrotic effect of activated autophagy is abated by inhibiting IRE1α and downstream XBP1 splicing; thus we provide unique insight into the relationship between autophagy and ER stress/UPR in IPF. These novel findings may have a significant impact on the design of new treatment strategies for IPF, which remains a devastating and incurable disease.

GRANTS

Funding for this project was provided by a Parker B. Francis Fellowship as well as an operating grant from the Manitoba Medical Services Foundation and Health Sciences Centre Foundation (to S. Ghavami). S. Shojaei is supported by a Mitacs Accelerate award and Health Sciences Centre Foundation. A. J. Halayko and I. M. Dixon received operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The project was also supported, in part, by awards from the Canada Research Chairs Program (to A. J. Halayko and M. Post). Support was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 1K08-HL-114882-01A1 (to A. A. Zeki). T. Klonisch received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada.

DISCLOSURES

J. Patterson is employed by Mannkind Corporation, which provided the IRE1alph inhibitor used in our experiments.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.G., A.A.Z., and A.J.H. conceived and designed research; S.G., B.Y., S.S., S.O., and J.A. performed experiments; S.G., S.S., J.A., and A.J.H. analyzed data; S.G., B.Y., A.A.Z., N.J.K., A.S., I.M.D., D.A.K., T.K., and A.J.H. interpreted results of experiments; S.G., B.Y., A.A.Z., and A.J.H. prepared figures; S.G., A.A.Z., and A.J.H. drafted manuscript; S.G., B.Y., A.A.Z., S.S., N.J.K., J.P., J.A., I.M.D., H.U., D.A.K., T.K., and A.J.H. edited and revised manuscript; S.G., B.Y., A.A.Z., S.S., N.J.K., S.O., A.S., J.P., J.A., A.R.M., I.M.D., H.U., D.A.K., M.P., T.K., and A.J.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Andrew Chan and Maya Juarez provided human lung sections from patients with IPF (UCDMC). Thomas Mahood, University of Manitoba, provided guidance for fibronectin quantitative PCR primer design.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson YI, Bowden DH. Pulmonary injury and repair. Organ culture studies of murine lung after oxygen. Arch Pathol Lab Med 100: 640–643, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahluwalia N, Shea BS, Tager AM. New therapeutic targets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Aiming to rein in runaway wound-healing responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190: 867–878, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0509PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araya J, Kojima J, Takasaka N, Ito S, Fujii S, Hara H, Yanagisawa H, Kobayashi K, Tsurushige C, Kawaishi M, Kamiya N, Hirano J, Odaka M, Morikawa T, Nishimura SL, Kawabata Y, Hano H, Nakayama K, Kuwano K. Insufficient autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304: L56–L69, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00213.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borges FT, Melo SA, Özdemir BC, Kato N, Revuelta I, Miller CA, Gattone VH II, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. TGF-β1-containing exosomes from injured epithelial cells activate fibroblasts to initiate tissue regenerative responses and fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 385–392, 2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012101031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budinger GR, Mutlu GM, Eisenbart J, Fuller AC, Bellmeyer AA, Baker CM, Wilson M, Ridge K, Barrett TA, Lee VY, Chandel NS. Proapoptotic Bid is required for pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4604–4609, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507604103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll B, Korolchuk VI, Sarkar S. Amino acids and autophagy: cross-talk and co-operation to control cellular homeostasis. Amino Acids 47: 2065–2088, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1775-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawley K, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Zeng Q, Patterson J, Gupta S, Samali A. Disruption of microRNA biogenesis confers resistance to ER stress-induced cell death upstream of the mitochondrion. PLoS One 8: e73870, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng YL, Xiong XZ, Cheng NS. Organ fibrosis inhibited by blocking transforming growth factor-β signaling via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 11: 467–478, 2012. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Y, Choi ME. Regulation of autophagy by TGF-β: emerging role in kidney fibrosis. Semin Nephrol 34: 62–71, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.du Bois RM. Strategies for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9: 129–140, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrd2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlop EA, Tee AR. mTOR and autophagy: a dynamic relationship governed by nutrients and energy. Semin Cell Dev Biol 36: 121–129, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. The impact of TGF-β on lung fibrosis: from targeting to biomarkers. Proc Am Thorac Soc 9: 111–116, 2012. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-023AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox E, Shojaie S, Wang J, Tseu I, Ackerley C, Bilodeau M, Post M. Three-dimensional culture and FGF signaling drive differentiation of murine pluripotent cells to distal lung epithelial cells. Stem Cells Dev 24: 21–35, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu MY, He YJ, Lv X, Liu ZH, Shen Y, Ye GR, Deng YM, Shu JC. Transforming growth factor-β1 reduces apoptosis via autophagy activation in hepatic stellate cells. Mol Med Rep 10: 1282–1288, 2014. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghavami S, Cunnington RH, Gupta S, Yeganeh B, Filomeno KL, Freed DH, Chen S, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, Ambrose E, Singal R, Dixon IM. Autophagy is a regulator of TGF-β1-induced fibrogenesis in primary human atrial myofibroblasts. Cell Death Dis 6: e1696, 2015. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghavami S, Gupta S, Ambrose E, Hnatowich M, Freed DH, Dixon IM. Autophagy and heart disease: implications for cardiac ischemia-reperfusion damage. Curr Mol Med 14: 616–629, 2014. doi: 10.2174/1566524014666140603101520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Hauff K, Stelmack GL, Schaafsma D, Sharma P, McNeill KD, Hynes TS, Kung SK, Unruh H, Klonisch T, Hatch GM, Los M, Halayko AJ. Statin-triggered cell death in primary human lung mesenchymal cells involves p53-PUMA and release of Smac and Omi but not cytochrome c. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803: 452–467, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Schaafsma D, Yeganeh B, Unruh H, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ. Geranylgeranyl transferase 1 modulates autophagy and apoptosis in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L420–L428, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Sharma P, Yeganeh B, McNeill KD, Klonisch T, Unruh H, Kashani HH, Schaafsma D, Los M, Halayko AJ. Mevalonate cascade regulation of airway mesenchymal cell autophagy and apoptosis: a dual role for p53. PLoS One 6: e16523, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghavami S, Sharma P, Yeganeh B, Ojo OO, Jha A, Mutawe MM, Kashani HH, Los MJ, Klonisch T, Unruh H, Halayko AJ. Airway mesenchymal cell death by mevalonate cascade inhibition: integration of autophagy, unfolded protein response and apoptosis focusing on Bcl2 family proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 1259–1271, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta SS, Zeglinski MR, Rattan SG, Landry NM, Ghavami S, Wigle JT, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, Dixon IM. Inhibition of autophagy inhibits the conversion of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiac myofibroblasts. Oncotarget 7: 78516–78531, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haga S, Nagata N, Okamura T, Yamamoto N, Sata T, Yamamoto N, Sasazuki T, Ishizaka Y. TACE antagonists blocking ACE2 shedding caused by the spike protein of SARS-CoV are candidate antiviral compounds. Antiviral Res 85: 551–555, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halwani R, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Jahdali H, Hamid Q. Role of transforming growth factor-β in airway remodeling in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 127–133, 2011. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0027TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haschek WM, Witschi H. Pulmonary fibrosis–a possible mechanism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 51: 475–487, 1979. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(79)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haspel JA, Choi AM. Autophagy: a core cellular process with emerging links to pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 1237–1246, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-0966CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández-Gea V, Ghiassi-Nejad Z, Rozenfeld R, Gordon R, Fiel MI, Yue Z, Czaja MJ, Friedman SL. Autophagy releases lipid that promotes fibrogenesis by activated hepatic stellate cells in mice and in human tissues. Gastroenterology 142: 938–946, 2012. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Im J, Hergert P, Nho RS. Reduced FoxO3a expression causes low autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts on collagen matrices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309: L552–L561, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00079.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawata M, Koinuma D, Ogami T, Umezawa K, Iwata C, Watabe T, Miyazono K. TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells is enhanced by pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. J Biochem 151: 205–216, 2012. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SI, Na HJ, Ding Y, Wang Z, Lee SJ, Choi ME. Autophagy promotes intracellular degradation of type I collagen induced by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1. J Biol Chem 287: 11677–11688, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuwano K, Kunitake R, Maeyama T, Hagimoto N, Kawasaki M, Matsuba T, Yoshimi M, Inoshima I, Yoshida K, Hara N. Attenuation of bleoECM-induced pneumopathy in mice by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L316–L325, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.2.L316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, Newcomb DC, Jones BR, Roldan J, Lane KB, Morrisey EE, Beers MF, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10562–10567, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawson WE, Crossno PF, Polosukhin VV, Roldan J, Cheng DS, Lane KB, Blackwell TR, Xu C, Markin C, Ware LB, Miller GG, Loyd JE, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar epithelial cells is prominent in IPF: association with altered surfactant protein processing and herpesvirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1119–L1126, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00382.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CM, Park JW, Cho WK, Zhou Y, Han B, Yoon PO, Chae J, Elias JA, Lee CG. Modifiers of TGF-β1 effector function as novel therapeutic targets of pulmonary fibrosis. Korean J Intern Med 29: 281–290, 2014. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.29.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenna S, Farina AG, Martyanov V, Christmann RB, Wood TA, Farber HW, Scorza R, Whitfield ML, Lafyatis R, Trojanowska M. Increased expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 65: 1357–1366, 2013. doi: 10.1002/art.37891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leppäranta O, Sens C, Salmenkivi K, Kinnula VL, Keski-Oja J, Myllärniemi M, Koli K. Regulation of TGF-β storage and activation in the human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis lung. Cell Tissue Res 348: 491–503, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Molina-Molina M, Abdul-Hafez A, Ramirez J, Serrano-Mollar A, Xaubet A, Uhal BD. Extravascular sources of lung angiotensin peptide synthesis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L887–L895, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00432.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Rayford H, Shu R, Zhuang J, Uhal BD. Essential role for cathepsin D in bleoECM-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L46–L51, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00442.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maguire JA, Mulugeta S, Beers MF. Multiple ways to die: delineation of the unfolded protein response and apoptosis induced by surfactant protein C BRICHOS mutants. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 101–112, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margaritopoulos GA, Romagnoli M, Poletti V, Siafakas NM, Wells AU, Antoniou KM. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and clinical evaluation of pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 21: 48–56, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margaritopoulos GA, Tsitoura E, Tzanakis N, Spandidos DA, Siafakas NM, Sourvinos G, Antoniou KM. Self-eating: friend or foe? The emerging role of autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BioMed Res Int 2013: 420497, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/420497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mora AL, Bueno M, Rojas M. Mitochondria in the spotlight of aging and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 127: 405–414, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI87440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni BB, Li B, Yang YH, Chen JW, Chen K, Jiang SD, Jiang LS. The effect of transforming growth factor β1 on the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in the annulus fibrosus cells under serum deprivation. Cytokine 70: 87–96, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.07.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel AS, Lin L, Geyer A, Haspel JA, An CH, Cao J, Rosas IO, Morse D. Autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One 7: e41394, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pechkovsky DV, Hackett TL, An SS, Shaheen F, Murray LA, Knight DA. Human lung parenchyma but not proximal bronchi produces fibroblasts with enhanced TGF-beta signaling and alpha-SMA expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43: 641–651, 2010. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0318OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pechkovsky DV, Prêle CM, Wong J, Hogaboam CM, McAnulty RJ, Laurent GJ, Zhang SS, Selman M, Mutsaers SE, Knight DA. STAT3-mediated signaling dysregulates lung fibroblast-myofibroblast activation and differentiation in UIP/IPF. Am J Pathol 180: 1398–1412, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poon A, Eidelman D, Laprise C, Hamid Q. ATG5, autophagy and lung function in asthma. Autophagy 8: 694–695, 2012. doi: 10.4161/auto.19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saveljeva S, Cleary P, Mnich K, Ayo A, Pakos-Zebrucka K, Patterson JB, Logue SE, Samali A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated induction of SESTRIN 2 potentiates cell survival. Oncotarget 7: 12254–12266, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sosulski ML, Gongora R, Danchuk S, Dong C, Luo F, Sanchez CG. Deregulation of selective autophagy during aging and pulmonary fibrosis: the role of TGFβ1. Aging Cell 14: 774–783, 2015. doi: 10.1111/acel.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan AY, Zimetbaum P. Atrial fibrillation and atrial fibrosis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 57: 625–629, 2011. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182073c78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tatler AL, Jenkins G. TGF-β activation and lung fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 9: 130–136, 2012. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-003AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vancheri C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an altered fibroblast proliferation linked to cancer biology. Proc Am Thorac Soc 9: 153–157, 2012. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-025AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volkmann K, Lucas JL, Vuga D, Wang X, Brumm D, Stiles C, Kriebel D, Der-Sarkissian A, Krishnan K, Schweitzer C, Liu Z, Malyankar UM, Chiovitti D, Canny M, Durocher D, Sicheri F, Patterson JB. Potent and selective inhibitors of the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 endoribonuclease. J Biol Chem 286: 12743–12755, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B, Jha JC, Hagiwara S, McClelland AD, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Transforming growth factor-β1-mediated renal fibrosis is dependent on the regulation of transforming growth factor receptor 1 expression by let-7b. Kidney Int 85: 352–361, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang YC, Zhang N, Van Crombruggen K, Hu GH, Hong SL, Bachert C. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in inflammatory airway disease: a key for understanding inflammation and remodeling. Allergy 67: 1193–1202, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeganeh B, Jager R, Gorman AM, Samali A, Ghavami S. Induction of Autophagy: Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response. In Autophagy: Cancer, Other Pathologies, Inflammation, Immunity, Infection, and Aging, edited by Netherland HM. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, 2015, p. 91–101. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801043-3.00005-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeganeh B, Mukherjee S, Moir LM, Kumawat K, Kashani HH, Bagchi RA, Baarsma HA, Gosens R, Ghavami S. Novel non-canonical TGF-β signaling networks: emerging roles in airway smooth muscle phenotype and function. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 26: 50–63, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeki AA, Yeganeh B, Kenyon NJ, Post M, Ghavami S. Autophagy in airway diseases: a new frontier in human asthma? Allergy 71: 5–14, 2016. doi: 10.1111/all.12761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Huang XR, Wei LH, Chung AC, Yu CM, Lan HY. miR-29b as a therapeutic agent for angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis by targeting TGF-β/Smad3 signaling. Mol Ther 22: 974–985, 2014. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao L, Ackerman SL. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in health and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18: 444–452, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]