Keywords: nerve regeneration, diabetic retinopathy, Rho kinases, Müller cells, reactive oxygen species, glutamine synthetase, α-smooth muscle actin, CoCl2, H2O2, hypoxia, oxidative stress, neural regeneration

Abstract

Rho kinase (ROCK) was the first downstream Rho effector found to mediate RhoA-induced actin cytoskeletal changes through effects on myosin light chain phosphorylation. There is abundant evidence that the ROCK pathway participates in the pathogenesis of retinal endothelial injury and proliferative epiretinal membrane traction. In this study, we investigated the effect of the ROCK pathway inhibitor Y-27632 on retinal Müller cells subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress. Müller cells were subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress by exposure to CoCl2 or H2O2. After a 24-hour treatment with Y-27632, the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay was used to assess the survival of Müller cells. Hoechst 33258 was used to detect apoptosis, while 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate was used to measure reactive oxygen species generation. A transwell chamber system was used to examine the migration ability of Müller cells. Western blot assay was used to detect the expression levels of α-smooth muscle actin, glutamine synthetase and vimentin. After treatment with Y-27632, Müller cells subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress exhibited a morphology similar to control cells. Y-27632 reduced apoptosis, α-smooth muscle actin expression and reactive oxygen species generation under oxidative stress, and it reduced cell migration under hypoxia. Y-27632 also upregulated glutamine synthetase expression under hypoxia but did not impact vimentin expression. These findings suggest that Y-27632 protects Müller cells against cellular injury caused by oxidative stress and hypoxia by inhibiting the ROCK pathway.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is a severe microvascular complication and the primary cause of blindness in diabetic patients. In 2010, approximately 800,000 patients suffered vision loss because of diabetic retinopathy, and 3,700,000 patients experienced visual impairment because of the disease; these numbers increased by 27% and 64%, respectively, compared with 1990 (Leasher et al., 2016). A series of pathological factors contribute to diabetic retinopathy in the early stage of diabetes, including hyperglycemia, hypoxia, oxidative stress and cytokines (Yan et al., 2016; Ye and Steinle, 2017). These factors can impact retinal Müller cells earlier than retinal vascular endothelial cells or pericytes (Hendrick et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2015). Therefore, studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms of Müller cell injury at the early stage of diabetic retinopathy.

The pathological changes in diabetic retinopathy, such as retinal endothelial injury and proliferative epiretinal membrane traction, have been shown to be related to the activity of the Rho kinase (ROCK) pathway (Huang et al., 2014). As a downstream effector of RhoA, ROCK regulates the aggregation and extension of the actin cytoskeleton by controlling the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of myosin light chain, thereby regulating various cellular processes, such as migration, chemotaxis, adhesion and contraction (Nourinia et al., 2017). In addition, ROCK increases contraction caused by angiotensin II, participates in the regulation of myocardiocyte apoptosis under hypoxia, and increases the calcium sensitivity of the aortic ring during oxidative stress (Araos et al., 2016; de Souza et al., 2016). However, whether ROCK is involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy caused by hypoxia and oxidative stress is unclear. In this study, retinal Müller cells were subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress, and the effects of the ROCK pathway inhibitor Y-27632 were examined in in vitro culture. Survival rate, cellular morphology, migration ability and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation were assessed. We also examined changes in the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), glutamine synthetase and vimentin in Müller cells subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress. Our study provides insight into the pathological mechanisms of Müller cell injury in the early stage of diabetic retinopathy.

Materials and Methods

In vitro culture of Müller cells

Mouse retinal Müller cells were purchased from Jenni Biological Technology Company (Guangzhou, China). The cells were cultured using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in an incubator with saturated humidity (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were passaged every 2–3 days.

Survival rate of Müller cells assessed by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

Müller cells were subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress using methods previously published by our group (Zhang et al., 2012a). Briefly, for the hypoxia model, the cells were divided into the following five groups: CoCl2, CoCl2 + 1 μM Y-27632, CoCl2 + 10 μM Y-27632, CoCl2 + 100 μM Y-27632 and control. For the oxidative stress model, the cells were divided into the following five groups: H2O2, H2O2 + 1 μM 27632, H2O2 + 10 μM Y-27632, H2O2 + 100 μM Y-27632 and control. The cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103/well. The cells were allowed to adhere to the wells, starved overnight, and cultured in medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Sijiqing Company, Hangzhou, China). Then, 200 μM CoCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 200 μM H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to cells in the hypoxia and oxidative stress groups, respectively, and incubated for an additional 24 hours. After cells treated by CoCl2 or μM H2O2 for 24 hours, the cells in the experimental groups were treated with Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich) at concentrations of 1, 10 or 100 μM and cultured at 37°C for 24, 48 or 72 hours. Subsequently, 20 μL MTT working solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well. After 4 hours at 37°C, the solution was discarded, and 150 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) was added to each well and agitated for 10 minutes. The absorbance of each well was measured at 490 nm with a microplate reader (Thermo).

Müller cell apoptosis assessed by Hoechst 33258 labeling

Three hypoxia groups (CoCl2, CoCl2 + Y-27632 and control) and three oxidative stress groups (H2O2, H2O2 + Y-27632 and control) were assessed for apoptosis. Müller cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 3 × 104/well (pre-coated with polylysine at 10 μg/mL). The cells were subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress for 24 hours. Y-27632 (10 μM) was added to the experimental groups for 24 hours, and the cells were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed with paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, labeled with Hoechst 33258 fluorescent dye (1 μg/mL; Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. The cells were observed, and images were captured under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to evaluate apoptosis after treating with anti-fade reagent.

ROS generation assessed with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA)

The cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 3 × 105/well and treated as described above. Then, 50 μL DCFH-DA (Beyotime) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The cells were observed, and images were acquired under a fluorescence microscope (excitation wavelength: 488 nm; emission wavelength: 525 nm).

Migration ability of Müller cells evaluated with the Transwell chamber assay

After resuspension, the cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103/well in the upper compartment of a Transwell chamber (Corning, New York, NY, USA) on an 8-μm filter membrane, and culture medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum (600 μL) was added to the lower compartment. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 12 hours, followed by treatment as described above. A swab was used to gently remove the cells from the front side of the upper chamber. The migrating cells were stained with crystal violet for 30 minutes and observed, and images were acquired under a light microscope (Nikon).

Expression levels of α-SMA, glutamine synthetase and vimentin assessed by western blot assay

The cells were seeded in a 6-well plate. When the cells reached ~80% confluency, they were treated as described above. The culture medium from the well was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. Then, 100 μL cell lysis buffer was added to the cells on ice for 30 minutes. The cells were scraped, ultrasonicated for 10 seconds, and centrifuged at 16,993 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Total proteins in the supernatant were separated by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The membrane was blocked with 10% skim milk at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by incubation with primary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse GAPDH monoclonal antibody (1:10,000), rabbit anti-mouse glutamine synthetase monoclonal antibody (1:2,000), rabbit anti-mouse α-SMA monoclonal antibody (1:30,000) or rabbit anti-mouse vimentin monoclonal antibody (1:8,000) (all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween 20 (TBST), followed by incubation with secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG, labeled with horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000) (Zhuangzhibio, Xi’an, China) at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were then washed three times with TBST for 10 minutes each, and thereafter incubated with chemiluminescence solution (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The bands were imaged on an Invitrogen E-Gel Imager (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA), and band intensities were quantified with Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). GAPDH served as an internal reference.

Statistical analysis

Data, expressed as the mean ± SD, were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate. After performing Levene’s homogeneity test for variance, the data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (least significant difference test was used to analyze multiple comparisons). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

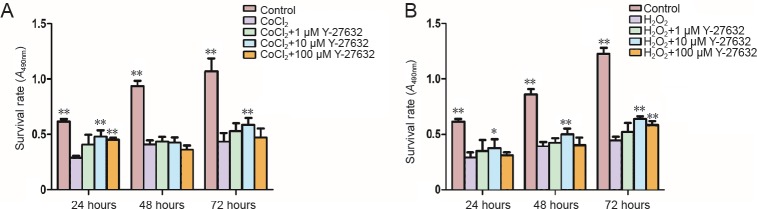

Effect of Y-27632 at different concentrations on the survival rate of Müller cells subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress

The MTT assay showed that the survival rate of Müller cells was significantly reduced by hypoxia as well as by oxidative stress (P = 0.000, P = 0.000). The different concentrations of Y-27632 at the various time points improved the survival rate of the cells. After a 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at different concentrations (1, 10 and 100 μM) at the early stage of injury, the cell survival rates increased compared with cells exposed to CoCl2 or H2O2 alone. Although Y-27632 did not display a concentration- or time-dependent effect, 10 μM Y-27632 exerted a significant cytoprotective effect after 24 hours of culture under the two conditions (P = 0.010, P = 0.049). Therefore, 10 μM Y-27632 was selected for the subsequent experiments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of Y-27632 on Müller cells under hypoxic (A) or oxidative stress (B) conditions.

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference test. All experiments were performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. CoCl2 group or H2O2 group.

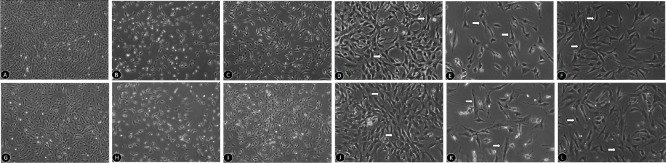

Morphological changes in Müller cells treated with Y-27632 and exposed to hypoxia or oxidative stress

Normal mouse retinal Müller cells are often long-spindle or triangular-shaped (Figure 2A, D, G, J). After exposure to hypoxia, these cells were reduced in number and displayed an irregular morphology with a loss of their original shape (Figure 2B, E). In comparison, 24 hours after 10 μM Y-27632 treatment, the number of Müller cells was significantly increased, and their morphology was similar to that of normal cells (Figure 2C, F). Similarly, after exposure to oxidative stress, the number of Müller cells was reduced, and irregular protuberances were visible, with an umbrella-like shape (Figure 2H, K). A 24-hour co-treatment with Y-27632 had a significant protective effect on Müller cells (Figure 2I, L).

Figure 2.

Morphological changes in Müller cells treated with Y-27632 and exposed to hypoxic or oxidative stress conditions.

(A–F) Morphological changes in Müller cells treated with 10 μM Y-27632 after 24 hours of hypoxia (original magnification: 40× in A–C and 100× in D–F). (A, D) Cellular morphologies in the control group: cells are often long spindle- or triangular-shaped. (B, E) Cellular morphologies in the CoCl2 group: the number of cells is reduced and the shape is irregular. (C, F) Cellular morphologies in the CoCl2 + Y27632 group: cell number increases and shape improves compared with the CoCl2 group. (G–L) Morphological changes in Müller cells treated with 10 μM Y-27632 after 24 hours of oxidative stress (original magnification: 40× in G–I and 100× in J–L). (G, I) Cellular morphologies in the control group. (H, K) Cellular morphologies in the H2O2 group. (I, L) Cellular morphologies in the H2O2 + Y27632 group. Arrows indicate Müller cells.

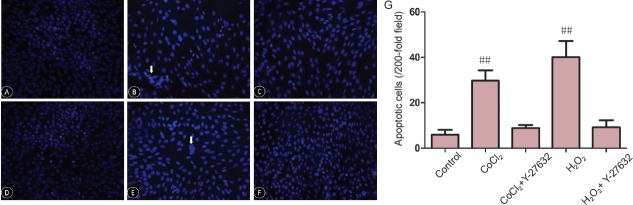

Effect of Y-27632 on apoptosis in Müller cells subjected to hypoxia or oxidative stress

Under hypoxic conditions, apoptosis of Müller cells was significantly increased, as assessed by Hoechst 33258 labeling. After a 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at 10 μM, apoptosis was significantly reduced (CoCl2 + Y-27632 group vs. control group, P = 0.032; CoCl2 + Y-27632 group vs. CoCl2 group, P = 0.01; Figure 3A–F). Similarly, a 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at 10 μM significantly reduced apoptosis caused by oxidative stress in Müller cells (H2O2 + Y-27632 group vs. control group, P < 0.01; H2O2 + Y-27632 group vs. H2O2 group, P = 0.049; Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Apoptotic changes in Müller cells (detected by Hoechst 33258 staining) treated with Y-27632 at 10 μM after 24 hours under oxidative stress, observed by fluorescence microscopy.

(A–C) Apoptosis in the control, CoCl2 and CoCl2 + Y27632 groups, respectively (×200). (D–F) Apoptosis in the control, H2O2 and H2O2 + Y27632 groups (× 200). Control group: apoptotic cells are rare. CoCl2 and H2O2 groups: the number of apoptotic cells increases, and Y27632 mitigates CoCl2- and H2O2-induced cell injury. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. (G) Quantitation of retinal Müller cell apoptosis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference test. All experiments were performed in triplicate. ##P < 0.01, vs. control group.

Impact of Y-27632 on ROS generation in Müller cells exposed to hypoxia or oxidative stress

A 24-hour incubation with 10 μM Y-27632 reduced ROS generation in Müller cells, as assessed by DCFH-DA fluorescence. Oxidative stress stimulated the generation of ROS, while Y-27632 significantly decreased ROS generation. Under hypoxia, the increase in ROS was insignificant, compared with the control group. There was no difference in ROS generation between cells treated with and without Y-27632 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ROS generation in retinal Müller cells incubated with 10 μM Y-27632 for 24 hours, detected by DCFH-DA and observed by fluorescence microscopy (original magnification, 100×).

(A–C) ROS generation in the negative control, CoCl2 and CoCl2 + Y27632 groups, respectively; (D–F) ROS generation in the positive control, H2O2 and H2O2 + Y27632 groups, respectively. Control group: No obvious ROS generation; CoCl2 and H2O2 groups: ROS generation increases, and Y27632 inhibits ROS generation induced by CoCl2 and H2O2. Arrows indicate ROS generated by Müller cells. ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

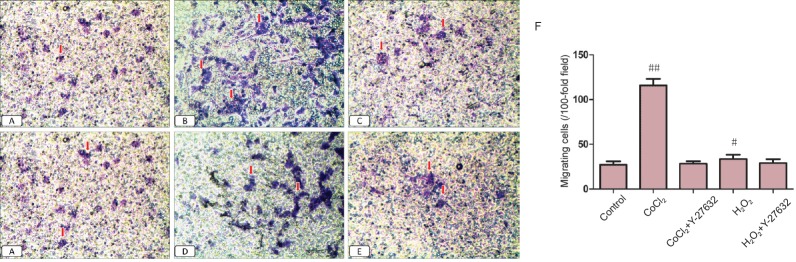

Effect of Y-27632 on the migration ability of Müller cells exposed to hypoxia or oxidative stress

Under hypoxia, the migration ability of Müller cells was improved. A 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at 10 μM reduced the migration ability. Under oxidative stress and after a 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at 10 μM, the migration ability also decreased significantly (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Impact of Y-27632 on the migration ability of Müller cells under hypoxia and oxidative stress.

(A–E) Control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + Y-27632, H2O2 and H2O2 + Y-27632 groups, respectively (original magnification, 100×). Control group: Migrating cells are rare. CoCl2 and H2O2 groups: the number of migrating cells increases, and Y27632 suppresses migration. (F) Quantitation of the migration ability of Müller cells. Arrows indicate migrated cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference test. All experiments were performed in triplicate. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. control group.

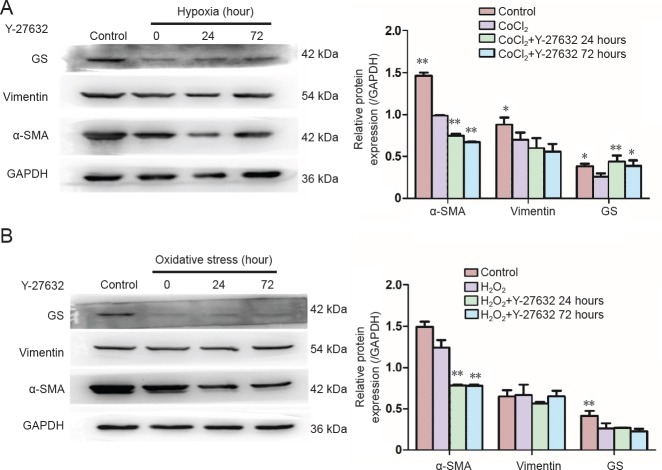

Impact of Y-27632 on α-SMA, glutamine synthetase and vimentin expression in Müller cells under hypoxia or oxidative stress

Under hypoxia, a statistically significant difference was observed in the expression of α-SMA and glutamine synthetase among all the groups (F = 30.677, P < 0.01; F = 26.934, P < 0.001). The pairwise comparison between the control group and each experimental group showed a significant difference (P < 0.01). The expression levels of α-SMA and glutamine synthetase were decreased significantly in the hypoxia group (P < 0.01 and P = 0.22, respectively). After treating with Y-27632 for 24 or 72 hours, the protein levels of α-SMA decreased further (P < 0.01, P < 0.01), while the protein levels of glutamine synthetase increased (P < 0.01, P = 0.018). A pairwise comparison between the experimental groups did not reveal a significant difference. Under hypoxia, no significant difference was found in vimentin expression among the groups (F = 1.04, P = 0.427; Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Changes in α-SMA, vimentin and GS expression levels in Müller cells under hypoxia and oxidative stress after 24- and 72-hour treatments with Y-27632 at 10 μM, assessed by western blot assay.

(A) α-SMA, vimentin and GS expression levels in Müller cells under hypoxia. (B) α-SMA, vimentin and GS expression levels in Müller cells under oxidative stress. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. CoCl2 group or H2O2 group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference test. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. α-SMA: α-Smooth muscle actin; GS: glutamine synthetase.

Under oxidative stress, there were statistically significant differences in the expression of α-SMA and glutamine synthetase among the groups (F = 849.3, P < 0.001; F = 10.01, P < 0.004). Pairwise comparisons between the control group and each experimental group revealed a significant difference (P < 0.01). The expression of α-SMA in the oxidative stress group was not significantly different (P = 0.092), while glutamine synthetase was decreased significantly (P < 0.01). After treatment with Y-27632 for 24 or 72 hours, the protein levels of α-SMA decreased (P < 0.01, P < 0.01), while the protein levels of glutamine synthetase remained unchanged (P = 0.857, P = 0.472). The pairwise comparison between experimental groups also revealed a significant difference (P < 0.01). No statistically significant difference was found in vimentin expression among the groups (F = 1.43, P = 0.30; Figure 6B).

Discussion

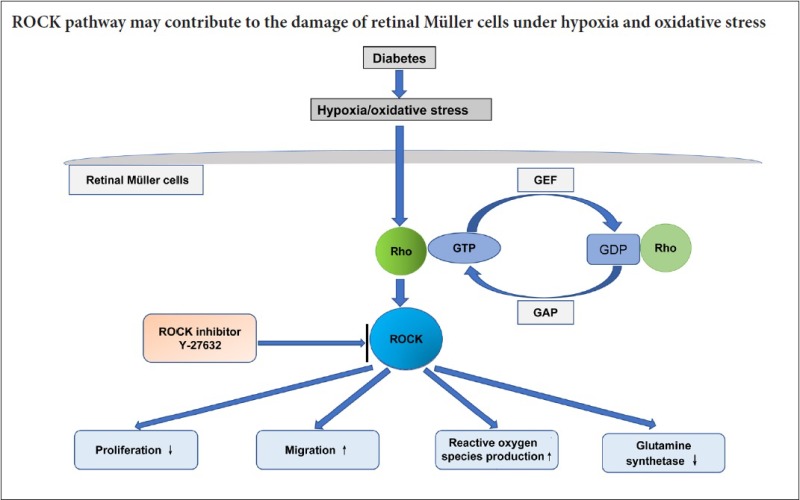

The Rho/ROCK signaling pathway is ubiquitously present in tissues and organs of the body, acting as a molecular switch. As a main downstream effector of Rho, ROCK exerts a regulatory effect on cell differentiation, cell cycle progression, proliferation, apoptosis and migration by modulating the activities of myosin light chain and myosin light chain phosphatase (Zhang et al., 2012b). The ROCK signaling pathway is strongly associated with the occurrence and development of diabetes. As a key downstream regulatory effector of tumor growth factor-β, ROCK reduces the high expression of α-SMA, myosin light chain phosphorylation, and collagen contraction induced by tumor growth factor-β in proliferative diabetic retinopathy/proliferative vitreoretinopathy injury. Therefore, the ROCK signaling pathway is a potential therapeutic target for proliferative vitreous retinal disease (Kita et al., 2008; Shu and Lovicu, 2017). Yamaguchi et al. (2016) found that a ROCK inhibitor could inhibit MYPT-1 phosphorylation, proliferation and migration induced by vascular endothelial growth factor in human retinal capillary endothelial cells, suggesting therapeutic potential for retinal hypoxic neurovascular disease. In addition, the ROCK inhibitor fasudil exerts a protective effect on vascular endothelium by inhibiting the adhesion of neutrophils, thereby reducing injury to endothelial cells (Yu et al., 2016). Furthermore, blockade of the ROCK pathway significantly decreases apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells exposed to hypoxia and hyperglycemia, thereby alleviating injury to the optic nerve (Yu et al., 2016).

Our current findings suggest that the ROCK signaling pathway plays a critical role in hypoxia and oxidative stress-induced injury in Müller cells, and that blockade of this pathway has a cytoprotective effect. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying diabetic retinopathy might involve activation of the ROCK pathway in Müller cells, which in turn reduces cell survival, increases cell migration, stimulates ROS generation and increases the expression of various downstream effector molecules.

Müller cells are glial cells that span the entire retina, and changes occur in these cells before endothelial cells and pericytes in the early stage of diabetic retinopathy. In the current study, Müller cells exposed to CoCl2 and H2O2 were used as models of hypoxic and oxidative stress injury, respectively. Morphological changes occurred in Müller cells soon after injury, along with an increase in apoptosis, ROS generation and migration ability. Our findings are in agreement with the changes observed in Müller cells subjected to hypoxia and oxidative stress in previous studies (Lu et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2015). MTT assay, Hoechst 33258 fluorescence staining, transwell chamber assay and DCFH-DA fluorescence assay were used to assess cell survival rate, cellular morphology, migration ability and ROS generation, respectively. A 24-hour treatment with Y-27632 at 10 μM exerted a cytoprotective effect on Müller cells. Glutamine synthetase, a protein expressed in Müller cells, is involved in the conversion of glutamic acid to glutamine. Damage to Müller cells leads to dysfunction in glutamic acid transport and the secretion of inflammatory factors, resulting in retinal neuronal injury (Chen et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). Additionally, under hypoxia, the expression of glutamine synthetase was reduced. Both 24- and 72-hour treatments with Y-27632 effectively increased expression, suggesting that Y-27632 promotes the recovery of glutamic acid transport in Müller cells (in a time-dependent manner). In cells exposed to oxidative stress, Y-27632 did not increase glutamine synthetase expression, perhaps because of the severity of injury or the short-lived activity of Y-27632.

Vimentin is a marker of retinal Müller cells. However, vimentin expression did not differ significantly among the groups, suggesting that it might not serve as an indicator of hypoxic or oxidative stress injury in Müller glia.

α-SMA is a myofibroblast marker. Following injury, α-SMA expression increases in Müller cells, which have the potential to differentiate into neurons (Jorstad et al., 2017). In the present study, the expression of α-SMA in the hypoxia and oxidative stress groups did not increase, which is not in accordance with our previous study. This discrepancy might be attributed to the severity of injury in Müller cells exposed to hypoxia and oxidative stress (Zhang et al., 2012a). After 24- and 72-hour treatments with Y-27632, α-SMA expression decreased, indicating that the inhibitor reduces injury to Müller cells. These findings indicate that the ROCK signaling pathway might contribute to the injury to Müller cells induced by hypoxia and oxidative stress.

In conclusion, the ROCK pathway might contribute to the damage to Müller cells induced by hypoxia and oxidative stress. While inhibiting the ROCK pathway might have therapeutic potential for diabetic retinopathy, it is necessary to investigate further the pathological mechanisms of hypoxic and oxidative stress injury to Müller cells. Although the ROCK pathway is closely related to the phenotypic changes in Müller cells, the underlying cell and biochemical changes are unclear. Numerous signaling pathways have been implicated in diabetic retinopathy, including P13K/AKT, ILK and HIF-1 (Xin et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016). Nevertheless, further studies are needed to more fully elucidate the role of the ROCK pathway and its interaction with other signaling pathways.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was financially supported by the Scientific and Technological Project of Shaanxi Province of China, No. 2016SF-010.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Financial support: This study was financially supported by the Scientific and Technological Project of Shaanxi Province of China, No. 2016SF-010. The funder had no involvement in the study design; data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation; paper writing; or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Ethical approval: This study received permission from the Animal Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University Medical College, China.

Data sharing statement: Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open peer review report:

Reviewer 1: Alonzo D Cook, Brigham Young University, USA.

Comments to authors: The justification for use of cobalt chloride as a surrogate for hypoxia and hydrogen peroxide as a surrogate for oxidative stress needs more justification. Otherwise, the paper is well written, has new data, is interesting to read, and the data support the conclusions, although the authors are somewhat weak in their concluding statements.

Reviewer 2: Li Yao, Wichita State University, USA.

Comments to authors: The manuscript presented a work to investigate the effect of ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632, on mice retinal Müller cell behavior in culturing under hypoxia and oxidative stress.

(Copyedited by Patel B, Frenchman B, Yu J, Li CH, Qiu Y, Song LP, Zhao M)

References

- Araos P, Mondaca D, Jalil JE, Yanez C, Novoa U, Mora I, Ocaranza MP. Diuretics prevent Rho-kinase activation and expression of profibrotic/oxidative genes in the hypertensive aortic wall. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;10:338–347. doi: 10.1177/1753944716666208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Mi M, Zhang Q, Wei N, Chen K, Xu H, Yuan J, Zhou Y, Lang H, Yu X, Wang B, Wang J, Tang Y, Chang H. Taurine buffers glutamate homeostasis in retinal cells in vitro under hypoxic conditions. Ophthalmic Res. 2010;44:105–112. doi: 10.1159/000312818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza P, Guarido KL, Scheschowitsch K, da Silva LM, Werner MF, Assreuy J, da Silva-Santos JE. Impaired vascular function in sepsis-surviving rats mediated by oxidative stress and Rho-kinase pathway. Redox Biol. 2016;10:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick AM, Gibson MV, Kulshreshtha A. Diabetic Retinopathy. Prim Care. 2015;42:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chen JB, Yang B, Shen H, Liang JJ, Luo Q. RhoA/ROCK pathway regulates hypoxia-induced myocardial cell apoptosis. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:884–888. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorstad NL, Wilken MS, Grimes WN, Wohl SG, VandenBosch LS, Yoshimatsu T, Wong RO, Rieke F, Reh TA. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature. 2017;548:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature23283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Hata Y, Arita R, Kawahara S, Miura M, Nakao S, Mochizuki Y, Enaida H, Goto Y, Shimokawa H, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ishibashi T. Role of TGF-beta in proliferative vitreoretinal diseases and ROCK as a therapeutic target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17504–17509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804054105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leasher JL, Bourne RR, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, Keeffe J, Naidoo K, Pesudovs K, Price H, White RA, Wong TY, Resnikoff S, Taylor HR, Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis from 1990 to 2010. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1643–1649. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Jiang YR, Qian J, Tao Y. Apelin-13 regulates proliferation, migration and survival of retinal Müller cells under hypoxia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourinia R, Nakao S, Zandi S, Safi S, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ahmadieh H. ROCK inhibitors for the treatment of ocular diseases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310378. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu DY, Lovicu FJ. Myofibroblast transdifferentiation: The dark force in ocular wound healing and fibrosis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;60:44–65. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SM, Deliyanti D, Figgett WA, Talia DM, de Haan JB, Wilkinson-Berka JL. Ebselen by modulating oxidative stress improves hypoxia-induced macroglial Muller cell and vascular injury in the retina. Exp Eye Res. 2015;136:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan TT, Li XF, Sun YM, Li YB, Su Y. Recent advances in understanding the biochemical and molecular mechanism of diabetic retinopathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;74:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, He C, Zhou T, Huang Z, Zhou L, Liu X. NGF increases VEGF expression and promotes cell proliferation via ERK1/2 and AKT signaling in Muller cells. Mol Vis. 2016;22:254–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lu Q, Gao S, Zhu Y, Gao Y, Xie B, Shen X. Pigment epithelium-derived factor regulates glutamine synthetase and l-glutamate/l-aspartate transporter in retinas with oxygen-induced retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40:1232–1244. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.990639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X, Rodrigues M, Umapathi M, Kashiwabuchi F, Ma T, Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Wang S, Hu J, Bhutto I, Welsbie DS, Duh EJ, Handa JT, Eberhart CG, Lutty G, Semenza GL, Montaner S, Sodhi A. Hypoxic retinal Muller cells promote vascular permeability by HIF-1-dependent up-regulation of angiopoietin-like 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3425–3434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217091110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Nakao S, Arita R, Kaizu Y, Arima M, Zhou Y, Kita T, Yoshida S, Kimura K, Isobe T, Kaneko Y, Sonoda KH, Ishibashi T. Vascular normalization by rock inhibitor: therapeutic potential of Ripasudil (K-115) eye drop in retinal angiogenesis and hypoxia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:2264–2276. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan PS, Tang S, Zhang HF, Guo YY, Zeng ZW, Wen Q. Nerve growth factor protects against palmitic acid-induced injury in retinal ganglion cells. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1851–1856. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye EA, Steinle JJ. Regulatory role of microRNA on inflammatory responses of diabetic retinopathy. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:580–581. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.205095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Luan X, Lan S, Yan B, Maier A. Fasudil, a Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor, attenuates traumatic retinal nerve injury in rabbits. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;58:74–82. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Feng Z, Li C, Zheng Y. Morphological and migratory alterations in retinal Muller cells during early stages of hypoxia and oxidative stress. Neural Regen Res. 2012a;7:31–35. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XH, Sun NX, Feng ZH, Wang C, Zhang Y, Wang JM. Interference of Y-27632 on the signal transduction of transforming growth factor beta type 1 in ocular Tenon capsule fibroblasts. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012b;5:576–581. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.05.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]